Abstract

Aims

This study assessed the association between attentional function and postural instability in older Japanese patients with diabetes.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 168 older patients with diabetes who were referred to an outpatient diabetic clinic between June and July 2013. The Trail Making Test-A (TMT-A) was used to evaluate attentional function. Posturography was used to evaluate postural sway. Indices of postural sway were the total length and the enveloped area. Analysis of covariance was used to estimate the multivariable-adjusted means of indices of postural sway according to tertile of TMT-A.

Results

After adjustment for age, sex, regular exercise, diabetic retinopathy, bilateral numbness and/or paresthesia in the feet, hemoglobin A1c level, quadriceps strength, and Mini-Mental State Examination score, patients with lower attentional function had higher postural sway length (tertile 3 vs. tertile 1, p = 0.010) and enveloped area (tertile 3 vs. tertile 1, p = 0.030) levels than those with higher attentional function.

Conclusions

Among older patients with diabetes who did not have dementia, patients with lower attentional function may have more postural instability than those with higher attentional function.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13340-015-0231-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Attentional function, Trail making test, Postural instability

Introduction

One of the major health problems among older people is falls, and unintentional falls are the leading cause of injury-related hospitalization and death [1]. Recently, it has been reported that older patients with diabetes are at increased risk of an injurious fall requiring hospitalization [2]. Previous studies have found that poor static balance is a major risk factor for falls among older patients with diabetes [2, 3]. Therefore, it is important to prevent postural instability of older patients with diabetes to prevent future falls.

Cognitive impairment is also a major health problem among older people. In older patients with diabetes, it is noteworthy that diabetes is a risk factor for cognitive impairment [4]. In particular, diabetes is frequently associated with deterioration of attentional function [5, 6]. Recent prospective studies have shown that deterioration of attentional function is associated with risk of falling among community-living older people [7, 8]. For prevention of future falls, it is important to determine whether attentional function is associated with postural instability in older patients with diabetes. To date, however, few studies have investigated this association [9]. The present study therefore aimed to assess the association between attentional function and postural instability in older Japanese patients with diabetes.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This cross-sectional study included 239 older patients with diabetes who were referred to an outpatient diabetic clinic between June and July 2013 at Shiga University of Medical Science Hospital (Otsu, Japan). Patients with dementia were excluded. Two hundred twenty-one outpatients (92.5 %) agreed to participate in the survey. We excluded 38 patients based on the following criteria: stroke, joint disease of the leg, spinal disease, leg fracture within the preceding 3 years, or use of a stick or wheelchair. We excluded a further 15 patients with missing data. A total of 168 patients, aged 60–87 years, were included in the analysis.

Procedures

The full details of this study have been described previously [10]. Attentional function was assessed using the Trail Making Test-A (TMT-A) [11]. The TMT-A was administered according to the guidelines presented by Spreen and Strauss [11]. The TMT-A requires a patient to connect 25 encircled numbers randomly arranged on a sheet of paper in ascending order as rapidly as possible (Fig. 1). Time to complete the test was recorded. The time of the test was counted in seconds, and we assessed that a longer time means lower attentional function [11].

Fig. 1.

An example of trail making test-A

General cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [12]. MMSE is a measure of global cognitive function consisting of 11 questions. In the study, a total score out of 30 was used.

The posturography test was used to evaluate postural sway in patients. We used a Gravicorder GP-5000 (Anima Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (Supplementary Fig. 1) consisting of an equilateral triangular footplate. Patients were instructed to maintain a static upright posture on the footplate with their feet together and eyes open (Supplementary Fig. 2). They were also instructed to focus on a small red circle that was 1.5 m away from where they were standing in a quiet, well-lit room. Recording time was 30 s, beginning after the posture of patients had stabilized. A statokinesigram (sway path of the center of pressure) was obtained from each patient (Supplementary Fig. 3). Indices of postural sway were the length (total length in cm, determined from the statokinesigram of the center of pressure movement over 30 s) and the enveloped area (overall sway area in cm2, enveloped by the outermost perimeter of the statokinesigram as traced by the movement of the center of pressure over 30 s).

Quadriceps strength was measured by isometric contraction of the knee extensors with a handheld dynamometer (μTas F-1; Anima Co., Ltd.). The higher value of the two measurements in both legs was used as maximum muscle strength. Demographic characteristics, health-related status, presence or absence of bilateral numbness and/or paresthesia in the feet (which have been described previously [10]), and medical history were obtained using a self-administered questionnaire. The patients were weighed while wearing light clothing, and height was measured without shoes. Blood pressure was measured using an automatic sphygmomanometer. Information on glycemic control and treatment was collected by a review of recent medical records. Hemoglobin (Hb) A1c was estimated as a National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program equivalent value and calculated using the formula HbA1c (%) = 1.02 × HbA1c (Japan Diabetes Society, %) + 0.25 % [13].

Statistical analysis

Participants in the study were classified into three groups according to tertile of TMT-A: tertile 1, those with higher attentional function (18–34 s); tertile 2 (35–49 s); tertile 3, those with lower attentional function (50–149 s). Differences in characteristics among the three groups were determined by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for age with adjustments for sex, an ANCOVA for continuous data with adjustments for age and sex, and a χ2 test for dichotomous data.

ANCOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used to estimate the multivariable-adjusted means and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) of indices of postural sway among the three groups. Data were adjusted for age, sex, regular exercise (presence or absence), diabetic retinopathy (presence or absence), bilateral numbness and/or paresthesia in the feet (presence or absence), HbA1c level, quadriceps strength, and MMSE score. In addition, patients were stratified into the following MMSE categories: ≥28 and ≤27. We also conducted ANCOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 J (IBM SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). All reported p values were two-tailed; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean age of the 168 patients was 71.2 years, and mean TMT-A was 47.4 s. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of 168 patients according to the tertile of TMT-A. Patients with lower attentional function (tertile 3) were older in the three groups (p < 0.001). They were more likely to be patients with insulin treatment (p = 0.079), those having lower MMSE scores (p = 0.075), and those with a history of falls (p = 0.087).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 168 older Japanese patients with diabetes according to the trail making test-A

| Tertile of TMT-A | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile 1 (higher attentional function) | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 (lower attentional function) | ||

| n | 55 | 57 | 56 | |

| TMT-A (s) | 29.1 ± 4.0 | 41.6 ± 4.5 | 71.3 ± 19.2 | |

| Age (years) | 68.0 (66.3–69.7) | 71.2 (69.6–72.8) | 74.4 (72.8–76.1) | <0.001 |

| Men, n (%) | 38 (69.1) | 37 (64.9) | 38 (67.9) | 0.889 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 8 (14.5) | 8 (14.0) | 10 (17.9) | 0.797 |

| Current drinker, n (%) | 21 (38.2) | 27 (47.4) | 20 (35.7) | 0.435 |

| Regular exercise, at least twice a week (≥30 min each), n (%) | 35 (63.6) | 37 (64.9) | 35 (62.5) | 0.965 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 16.8 (14.0–19.6) | 19.0 (16.3–21.6) | 19.3 (16.6–22.1) | 0.403 |

| Type 1 diabetes, n (%) | 5 (9.1) | 3 (5.3) | 3 (5.4) | 0.801 |

| Treated with insulin, n (%) | 15 (27.3) | 14 (24.6) | 24 (42.9) | 0.079 |

| Diabetic retinopathy, n (%) | 9 (16.4) | 9 (15.8) | 13 (23.2) | 0.529 |

| Bilateral numbness and/or paresthesia in the feet, n (%) | 6 (10.9) | 7 (12.3) | 13 (23.2) | 0.143 |

| History of ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 7 (12.7) | 12 (21.1) | 10 (17.9) | 0.502 |

| Medication for hypertension, n (%) | 32 (58.2) | 37 (64.9) | 37 (66.1) | 0.649 |

| Medication for dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 32 (58.2) | 36 (63.2) | 30 (53.6) | 0.586 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.9 (22.9–25.0) | 24.0 (23.1–25.0) | 24.4 (23.3–25.4) | 0.847 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 132.9 (127.4–138.4) | 138.7 (133.5–143.9) | 134.9 (129.4–140.3) | 0.294 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 69.8 (67.2–72.5) | 72.0 (69.5–74.5) | 70.1 (67.5–72.7) | 0.138 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.41 (1.30–1.51) | 1.51 (1.41–1.61) | 1.38 (1.27–1.48) | 0.150 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.0 (6.8–7.3) | 7.1 (6.9–7.4) | 7.4 (7.2–7.6) | 0.102 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 73.0 (68.7–77.3) | 71.1 (67.1–75.2) | 68.0 (63.7–72.2) | 0.283 |

| Quadriceps strength (kg) | 31.0 (28.4–33.6) | 29.1 (26.7–31.5) | 28.5 (25.9–31.0) | 0.380 |

| Mini-mental state examination (score) | 29.0 (28.5–29.5) | 28.4 (27.9–28.8) | 28.2 (27.7–28.7) | 0.075 |

| History of falls, n (%) | 5 (9.1) | 9 (15.8) | 16 (28.6) | 0.087 |

TMT-A is shown as mean ± standard deviation. Continuous, normally distributed data were analyzed by analysis of covariance with adjustments for age and sex, and they are shown as age- and sex-adjusted means (95 % confidence intervals). Dichotomous data were analyzed by χ2 test and are shown as number of patients (%)

TMT trail making test, HDL high-density lipoprotein, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

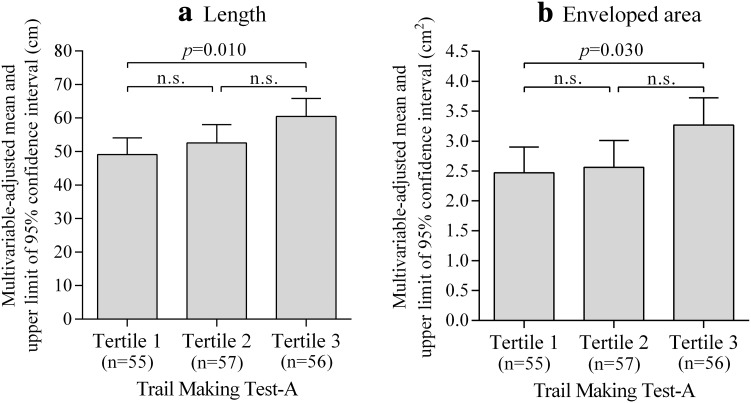

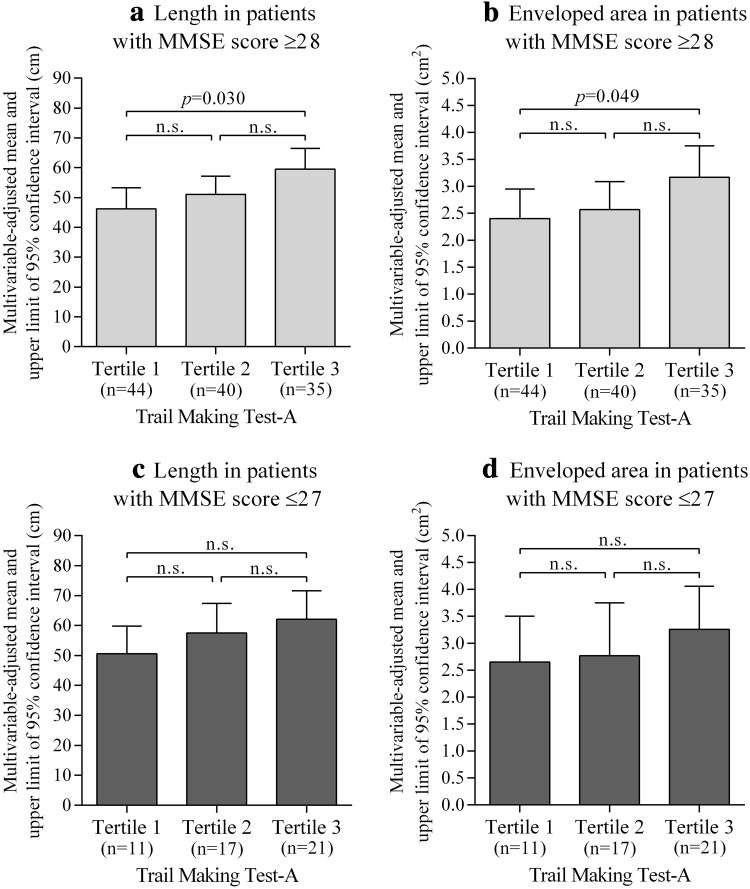

Figure 2 shows multivariable-adjusted means of length and enveloped area levels in the posturography test according to tertile of TMT-A. After adjustment for confounding factors, patients with lower attentional function had higher postural sway length (tertile 3 vs. tertile 1, p = 0.010) and enveloped area (tertile 3 vs. tertile 1, p = 0.030) levels than those with higher attentional function. We observed similar results in patients with MMSE score ≥28 (mean 29.5), and the tendency of results did not change in patients with MMSE score ≤27 (mean 26.0) (Fig. 3). Although the statistical power decreased because of small sample size, the tendency of these results did not change by sex-specific analysis. Additionally, we observed similar results when we analyzed 99 patients aged ≥70 years (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Multivariable-adjusted means of a length and b enveloped area levels in the posturography test according to tertile of trail making test-A. Tertile 1, those with higher attentional function (18–34 s); tertile 2 (35–49 s); tertile 3, those with lower attentional function (50–149 s). Length and enveloped area levels were analyzed by analysis of covariance with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons and are shown as adjusted means and upper limits of 95 % confidence intervals. Data were adjusted for age, sex, regular exercise, diabetic retinopathy, bilateral numbness and/or paresthesia in the feet, hemoglobin A1c level, quadriceps strength, and mini-mental state examination score. n.s. not significant

Fig. 3.

Multivariable-adjusted means of indices of postural sway according to the tertile of trail making test-A in the MMSE categories; a length in those with MMSE score ≥28; b enveloped area in those with MMSE score ≥28; c length in those with MMSE score ≤27; d enveloped area in those with MMSE score ≤27. Tertile 1, those with higher attentional function (18–34 s); tertile 2 (35–49 s); tertile 3, those with lower attentional function (50–149 s). Length and enveloped area levels were analyzed by analysis of covariance with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons and are shown as adjusted means and upper limits of 95 % confidence intervals. Data were adjusted for age, sex, regular exercise, diabetic retinopathy, bilateral numbness and/or paresthesia in the feet, hemoglobin A1c level, quadriceps strength, and MMSE score. MMSE mini-mental state examination, n.s. not significant

Discussion

The main findings of the present study indicated that after adjustment for confounding factors, among older patients with diabetes who did not have dementia, patients with lower attentional function had higher postural sway length and enveloped area levels than those with higher attentional function. It has been reported that physical function, such as muscle strength, and regular exercise are associated with postural instability [14, 15]. In the present study, attentional function, which was evaluated by the TMT-A, was associated with postural instability after adjustment for these factors. Therefore, not only physical function but also attentional function may be associated with postural instability among older patients with diabetes.

Patients in the study who had lower attentional function had higher postural sway length and enveloped area levels in those with MMSE score ≥28 (i.e., patients with normal cognitive function). Even if cognitive function is normal, it is necessary to be careful about the deterioration of attentional function for prevention of postural instability among older patients with diabetes.

In the present study, patients with insulin treatment had significantly lower attentional function than those without insulin treatment [age- and sex-adjusted mean TMT-A (second); 53.5 vs. 44.6, p = 0.010) (data not shown). Additionally, patients with HbA1c levels ≥7.0 % were more likely to have lower attentional function than those with HbA1c levels <7.0 % [age- and sex-adjusted mean TMT-A (second); 50.3 vs. 44.9, p = 0.183] (data not shown). Patients using insulin or patients with poor glycemic control may have lower attentional function. It has been reported that deterioration of attentional function recovers with improvement of glucose control for 2 weeks [6]. Therefore, medical workers need to intervene to recover attentional function that has deteriorated.

The mechanism for the increased postural instability of patients with lower attentional function is unclear. However, it has been reported that attention is involved in the processing of sensory information [16]. Normal postural control requires the integration of visual, somatosensory, and vestibular inputs as well as the adaptation of these inputs to changes in task and environmental context [17]. Deterioration of attentional function may be associated with postural instability through processing of sensory information.

There were several limitations to the present study. First, the cross-sectional design cannot prove causality. Therefore, further investigation in a prospective study is necessary. Second, the subjects were limited to the patients of one university hospital. Third, the sample size was low. Hence, further investigation with a larger sample size is necessary to confirm these results. Fourth, we did not evaluate whether symptoms of bilateral numbness and paresthesia in the feet were due to diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Finally, attentional function of patients was evaluated by one kind of test. Additionally, it has been reported that executive function is associated with falls in older adults [7]. Executive function can be assessed with TMT-B. Unfortunately, we did not assess executive function by the TMT-B. Hence, a further investigation that assesses the executive function is necessary to confirm our results.

In conclusion, attentional function as evaluated by TMT-A was associated with postural instability among older Japanese patients with diabetes who do not have dementia. Increased postural instability is a burden for older patients with diabetes and their families because it is a major risk factor for falls. Therefore, it is thought that early intervention for physical and attentional function is important.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fund for Care Prevention from NPO Biwako Health and Welfare Consortium and Shiga Prefecture. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (grant no. 25862144, 15K20762).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human rights statement and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (Shiga University of Medical Science, an Ethical Committee) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later revisions. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

References

- 1.Centers for disease control and prevention. injury prevention and control: data and statistics (WISQARS). http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed 3 April 2015.

- 2.Yau RK, Strotmeyer ES, Resnick HE, et al. Diabetes and risk of hospitalized fall injury among older adults. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3985–3991. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz AV, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Diabetes-related complications, glycemic control, and falls in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:391–396. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng G, Huang C, Deng H, et al. Diabetes as a risk factor for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Intern Med J. 2012;42:484–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai T, Yokono K. Comprehensive studies of cognitive impairment of the elderly with type 2 diabetes. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2006;6:159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2006.00343.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araki A, Ito H. Glucose metabolism, advanced glycation end products, and cognition. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2004;4:S108–S110. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2004.00169.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirelman A, Herman T, Brozgol M, et al. Executive function and falls in older adults: new findings from a 5 year prospective study link fall risk to cognition. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murata S, Tsuda A, Inatani F. The relationship of physical and cognitive factors with falls in the elderly disabled at home: one year follow-up study. Jpn J Behav Med. 2005;11:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MA, Else JE, Paul L, et al. Functional living in older adults with type 2 diabetes: executive functioning, dual task performance, and the impact on postural stability and motor control. J Aging Health. 2014;26:841–859. doi: 10.1177/0898264314534896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morimoto A, Sonoda N, Ugi S, et al. Association between symptoms of bilateral numbness and/or paresthesia in the feet and postural instability in Japanese patients with diabetes. Diabetol Int. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13340-015-0214-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spreen O, Strauss E. Trail making test. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms and commentary. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashiwagi A, Kasuga M, Araki E, et al. International clinical harmonization of glycated hemoglobin in Japan: from Japan diabetes society to national glycohemoglobin standardization program values. J Diabetes Invest. 2012;3:39–40. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orr R. Contribution of muscle weakness to postural instability in the elderly. A systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46:183–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allet L, Armand S, de Bie RA, et al. The gait and balance of patients with diabetes can be improved: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2010;53:458–466. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1592-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu YF, Hämäläinen JA, Waszak F. Both attention and prediction are necessary for adaptive neuronal tuning in sensory processing. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manchester D, Woollacott M, Zederbauer-Hylton N, et al. Visual, vestibular and somatosensory contributions to balance control in the older adult. J Gerontol. 1989;4:118–127. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.5.M118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.