Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to clarify trends in clinical performance in diabetic patients over a 12-year period in primary care clinics and hospitals in Japan.

Materials and methods

The Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey records medical performance in diabetic patients in primary care clinics and hospitals in Shiga Prefecture, Japan. In this study, laboratory data, modality of treatment for diabetes, and status of examination for diabetic complications were examined using results of surveys in 2000, 2006, and 2012. The study included 17,870, 18,398, and 24,219 patients for those years, respectively.

Results

Mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level significantly improved over 12 years and was significantly lower in the primary care clinics group than the hospitals group (7.3 ± 1.5 vs. 7.4 ± 1.4 % in 2000, 7.2 ± 1.2 vs. 7.4 ± 1.3 % in 2006, and 6.9 ± 1.0 vs. 7.1 ± 1.1 % in 2012). With regard to diabetic treatment modality, patients treated in hospitals used insulin more frequently than those in primary care clinics. The proportion of patients examined for diabetic complications increased but did not reach 50 % in 2012. Mean blood pressure and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were lowered, but blood pressure control was worse than that of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Conclusions

This study shows that glycemic control in both primary care clinics and hospitals has improved and was almost acceptable. However, examinations for diabetic complications and the control of blood pressure were still insufficient.

Keywords: Clinical survey, Diabetes mellitus, Japanese, Medical performance

Introduction

The number of diabetic patients has been increasing in Asia, including in Japan. The International Diabetes Federation reports that four Asian countries (China, India, Indonesia, and Japan) were ranked in the top ten countries/territories in the world for number of diabetic patients [1]. It is presumed that 7.2 million adults in Japan are diabetic, and the diabetic population of Southeast Asia has been expanding rapidly and has reached almost one fifth of all cases worldwide [1]. Diabetes leads to serious problems in various parts of the body and is a leading cause of death when appropriate treatment is not received. In recent years, new drugs have been developed for treating diabetes, but there is a question of whether glycemic control has improved. It is important to clarify the current status of diabetic medical performance and its trends to improve glycemic control.

In this study, we analyzed three cross-sectional data collections from the Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey performed in 2000, 2006, and 2012. This survey was targeted to all primary care clinics (PCCs) and hospitals in Shiga prefecture. We compared 12-year trends between PCCs and hospitals regarding glycemic control, diabetic treatment, examination of diabetic complications, and control of blood pressure and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. In this study, most PCCs were run by general practitioners (GPs) and most hospitals by diabetologists. There are very few reports comparing diabetes management, including glycemic control and diabetic treatment, between PCCs and hospitals or GPs and diabetologists in Japan [2].

As Shiga prefecture falls around the mean of all prefectures in Japan with respect to economic activity, such as gross regional product and population, results of this study may be a sufficient representation of medical data of diabetic patients in all of Japan [3]. Thus, results of this study suggest the actual medical performance of diabetic patients treated by GPs or diabetologists throughout Japan.

Materials and methods

Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey

Shiga prefecture is located in the central part of Japan. The population was 1,380,361 in 2005 and 1,410,777 in 2010 [3]. The Shiga Medical Association established the Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey in 2000. The association has carried out this large-scale survey of medical care in diabetes, which was targeted to all medical institutions in Shiga, every 6 years since 2000. The numbers of medical institutions (PCCs/hospitals) in Shiga were 912 (852/60) in 2000, 992 (932/60) in 2006, and 1,076 (1,017/59) in 2012. [4]. In 2000, registration forms were sent to all medical institutions in Shiga. However, for 2006 and 2012, registration forms were only sent to medical institutions that were interested in participating in this study. Registration forms were sent to 266 (242/24) and 241 (215/26) medical institutions (PCCs/hospitals) for 2006 and 2012, respectively. We are unable to describe the exact number of participating medical institutions as, for the purpose of anonymity, registration forms do not contain the name of the participating medical institution. Data were collected in November 2000 and in October and November in 2006 and 2012.

We researched weight, height, blood pressure, the most recent data for glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), other laboratory data, drug therapy, and information on retinal screening and examination of microalbuminuria within 1 year. Each PCC and hospital collected these data in a registration form, and these were collected through each regional medical association. In this study, we analyzed patients aged ≥20 years for a total of 17,870 patients in 2000, 18,398 in 2006, and 24,219 in 2012. The majority of blood examination data were not fasting; fasting data were 31.7 % in 2000, 20.6 % in 2006, and 14.2 % in 2012. The value for HbA1c, which was measured using the methods of the Japan Diabetes Society (JDS), is estimated as the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP)-equivalent value by the following formula: HbA1c (NGSP) (%) = 1.02 × HbA1c (JDS) (%) + 0.25 [5]. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg [6] or taking antihypertensive medications.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ characteristics and differences between patients treated in PCCs and those treated in hospitals for each survey year were compared using t tests for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. A regression analysis was used to examine the trend in HbA1c values. A logistic analysis was used to examine the trend in change of diabetic treatment modality and prevalence of hypertension. P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 for Windows (IBM Corp., USA).

Results

Characteristics

Clinical characteristics of each study population are shown in Table 1. Percentages of patients treated in PCCs were 41.0 % in 2000, 47.5 % in 2006, and 38.9 % in 2012. Mean patient age was 65.1 ± 11.7 years in 2000, 66.7 ± 11.8 years, in 2006 and 66.7 ± 12.2 years in 2012 (P for trend <0.001). Mean body mass index (BMI) increased from 23.7 ± 3.7 kg/m2 in 2000 to 24.6 ± 4.3 kg/m2 in 2012 (P for trend <0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey in 2000, 2006, and 2012

| PCCs | Hospitals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2006 | 2012 | 2000 | 2006 | 2012 | |

| Number | 7335 | 8741 | 9428 | 10534 | 9657 | 14815 |

| Men (%) | 50.7 | 53.2 | 54.5 | 53.2* | 58.0* | 60.9* |

| Age (year) | 65.8 ± 11.4 | 67.7 ± 11.3 | 68.6 ± 11.5 | 64.6 ± 11.9* | 65.7 ± 12.1* | 65.5 ± 12.4* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 138.7 ± 17.0 | 135.5 ± 15.7 | 132.1 ± 14.8 | 136.0 ± 18.5* | 132.9 ± 16.6* | 131.2 ± 16.7* |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 78.3 ± 10.4 | 76.5 ± 10.1 | 74.4 ± 10.2 | 75.2 ± 10.8* | 74.0 ± 10.5* | 73.3 ± 11.7* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.1 ± 3.6 | 24.3 ± 3.8 | 24.7 ± 4.1 | 23.5 ± 3.6* | 24.0 ± 3.9* | 24.6 ± 4.4 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 1.0 | 7.4 ± 1.4* | 7.4 ± 1.3* | 7.1 ± 1.1* |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 200.3 ± 34.3 | 199.9 ± 33.3 | 190.0 ± 34.0 | 195.9 ± 36.3* | 194.6 ± 36.7* | 182.7 ± 36.8* |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 155.9 ± 100.8 | 142.5 ± 87.2 | 145.8 ± 107.4 | 141.1 ± 102.5* | 144.0 ± 96.5 | 147.3 ± 109.9 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 52.5 ± 15.9 | 54.5 ± 15.8 | 55.6 ± 15.4 | 56.7 ± 17.0* | 55.5 ± 16.7* | 54.8 ± 16.0* |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 118.4 ± 31.0 | 117.8 ± 29.8 | 109.7 ± 28.6 | 112.3 ± 31.8* | 111.1 ± 32.2* | 101.5 ± 29.2* |

| Non-HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 148.5 ± 34.4 | 145.5 ± 33.5 | 134.3 ± 33.1 | 139.7 ± 35.9* | 139.2 ± 36.4* | 129.2 ± 34.7* |

| Use of antihypertensive drugs (%) | 52.3 | 56.2 | 63.9 | 41.0* | 49.7* | 53.3* |

| Use of lipid lowering drugs (%) | 26.8 | 32.4 | 47.5 | 25.8 | 32.3 | 46.8 |

Data are % or mean ± standard deviation

PCCs primary care clinics, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein

* P < 0.05, p value for difference between PCCs and hospitals for each survey year

HbA1c values

Mean HbA1c levels significantly improved over 12 years (mean ± standard deviation (SD) 7.3 ± 1.4 % in 2000; 7.3 ± 1.3 % in 2006; 7.1 ± 1.1 % in 2012; P for trend <0.001); mean HbA1c levels for patients treated in PCCs were significantly lower than for those treated in hospitals (Table 1). The proportion of patients with HbA1c levels <7.0 %, which was a target level to prevent diabetic microangiopathy [7], was 48.4 % in 2000, 48.2 % in 2006, and 57.3 % in 2012. As shown in Fig. 1, in the PCC group, the proportion of patients with HbA1c levels <7.0 % was 51.5 % in 2000, 53.9 % in 2006, and 62.4 % in 2012 versus 46.1, 42.1, and 54.1 %, respectively, in the hospitals group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients according to categories by glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in primary care clinics (PCCs) and hospitals in 2000, 2006, and 2012

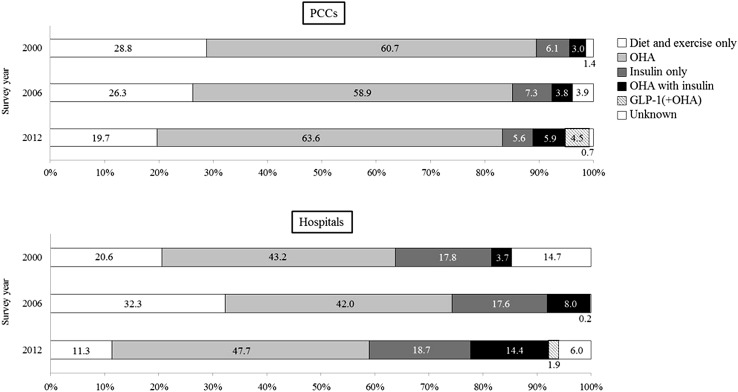

Diabetic treatment modality

The proportion of all patients on diet and exercise only (no medication), which was 24.2 % in 2000 and 29.4 % in 2006, fell to 14.6 % in 2012 (P for trend <0.001). Orally administered hypoglycemic agents (OHA) were the most frequently used treatments: 50.9 % in 2000 and 50.0 % in 2006, which slightly increased to 53.9 % in 2012 (P for trend <0.001). The proportion of patients on insulin only did not differ over the 12 years (13.1 % in 2000, 12.7 % in 2006, and 13.6 % in 2012, P for trend =0.101). By contrast, the proportion of patients with a combination of OHA and insulin therapy significantly increased (3.4 % in 2000, 6.0 % in 2006, and 11.1 % in 2012, P for trend <0.001). Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists as a new treatment were added in 2012. These trends were confirmed in both PCCs and hospitals (Fig. 2). There were a few differences between PCCs and hospitals: patients treated in PCCs used more OHA and less insulin than patients in hospitals.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of each therapeutic modality among patients in primary care clinics (PCCs) and hospitals in 2000, 2006, and 2012. OHA orally administered hypoglycemic agents, GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide-1

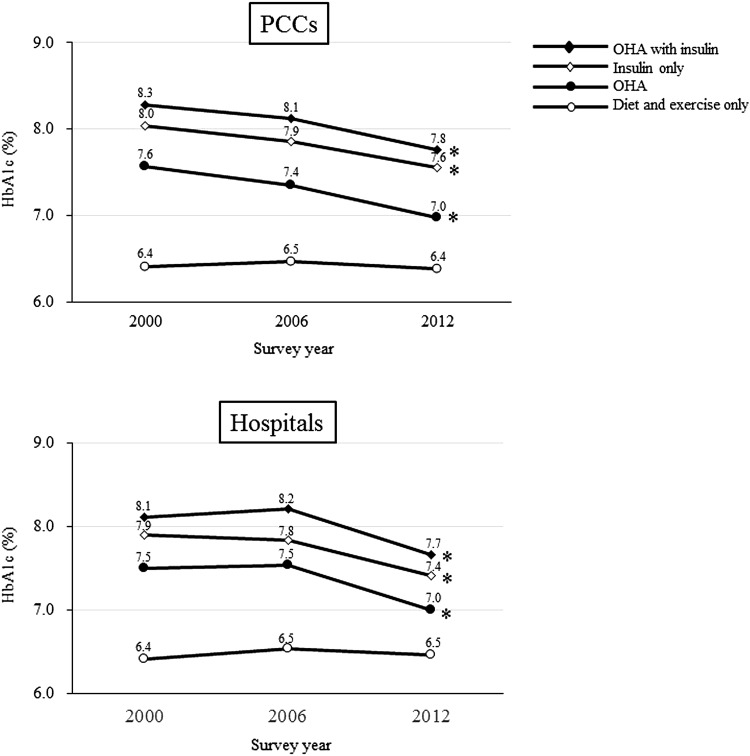

Glycemic control by diabetic treatment

Mean HbA1c levels in the diet and exercise only group were the lowest of all treatment groups and did not change over 12 years (6.4 ± 1.0 % in 2000, 6.5 ± 0.9 % in 2006, and 6.4 ± 0.8 % in 2012). The rank order of mean HbA1c levels starting with the lowest by diabetic treatment modality were diet and exercise only, OHA, insulin, and OHA plus insulin therapy (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Trends of mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels by diabetic treatment among patients in primary care clinics (PCCs) and hospitals from 2000 to 2012. OHA orally administered hypoglycemic agents. *P for trend <0.001

Trends in glycemic control were almost the same in the OHA group, insulin group, and OHA with insulin group. Mean HbA1c levels of each group improved in 2012 both in PCCs and hospitals (P for trend <0.001). While the mean HbA1c levels of patients treated in PCCs improved continuously from 2000 to 2012, levels of patients in hospitals did not change from 2000 to 2006 but improved from 2006 to 2012 (Fig. 3).

Examination of microalbuminuria and retinal screening

Quantitative measurement of urinary albumin of patients within 1 year increased over the 12 years (20.7 % in 2000, 27.4 % in 2006, and 37.2 % in 2012, P for trend <0.001). The proportion of patients who took urinary albumin measurement in hospitals were higher than that in PCCs (Fig. 4a). With stratification by HbA1c level, as glycemic control worsened, it tended to increase the proportion of patients with urinary albumin measurement in both groups (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

a Trends of proportion of patients examined for urinary albumin within 1 year in primary care clinics (PCCs) and hospitals from 2000 to 2012. b Proportion of patients examined for urinary albumin within 1 year by glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in PCCs and hospitals in 2000, 2006, and 2012. *P for trend <0.001

The number of patients who received retinal screening within 1 year increased slightly (44.8 % in 2000, 46.5 % in 2006, and 49.1 % in 2012, P for trend <0.001), with patients treated in hospitals receiving retinal screening more frequently than those in PCCs (Fig. 5a). With stratification by HbA1c, as glycemic control worsened, the proportion of patients screened tended to be higher both groups. In PCCs, the rate screening rose slightly in 2012 compared with 2000, whereas there was no increase in hospitals over time except for the category of HbA1c < 6 % (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Trends of proportion of patients a given retinal screening within 1 year in primary care clinics (PCCs) and hospitals from 2000 to 2012 and b of patients with retinal screening within 1 year by glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in PCCs and hospitals in 2000, 2006, and 2012. *P for trend <0.001

Control of blood pressure and LDL-cholesterol

The prevalence of hypertension significantly increased, from 66.7 % in 2000, to 66.4 % in 2006, and to 69.1 % in 2012, P for trend <0.001. Mean blood pressure improved over the 12 years both in PCCs and hospitals (Table 1), and the proportion of patients who met the Japan Diabetes Society guidelines of 130/80 mmHg [8] increased (Table 2). However, the control rate remained low (24.3 % in 2000, 29.0 % in 2006, and 37.6 % in 2012) and has lowered for patients controlled by antihypertensive drugs. The control rate of systolic blood pressure (SBP) was lower than that of diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The proportion of patients whose SBP was <130 mmHg was 30.2 % in 2000, 35.2 % in 2006, and 44.0 % in 2012. Similarly, the proportion of patients whose DBP was <80 mmHg was 52.5 % in 2000, 59.8 % in 2006, and 67.8 % in 2012. The proportion of patients with adequate blood pressure was higher in hospitals than in PCCs.

Table 2.

Control of blood pressure and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol among the patients in primary care clinics (PCCs) and hospitals

| PCCs | Hospitals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2006 | 2012 | 2000 | 2006 | 2012 | |

| Blood pressure | ||||||

| ≥140/90 mmHg or on antihypertensive drug (%) | 69.2 | 69.7 | 71.7 | 64.7* | 62.4* | 67.1* |

| <130/80 mmHg (%) | 19.5 | 24.8 | 33.9 | 28.2* | 34.1* | 40.5* |

| <130/80 on antihypertensive drug (%) | 8.9 | 16.1 | 28.0 | 17.0* | 25.9* | 35.4* |

| LDL-cholesterol | ||||||

| ≥140 mg/dl or on lipid lowering drug (%) | 42.6 | 49.0 | 57.4 | 40.8 | 47.0* | 55.0* |

| <120 mg/dl (%) | 52.9 | 54.6 | 65.7 | 62.0* | 63.8* | 75.7* |

| <120 mg/dl on lipid lowering drug (%) | 43.8 | 55.8 | 72.3 | 58.2* | 68.2* | 83.1* |

PCCs primary care clinics

* P < 0.05, p value for difference between PCCs and hospitals for each survey year

Total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol levels improved over the 12 years, although triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol levels did not change (Table 1). Control of LDL-cholesterol levels has also improved, with patients treated in hospitals being controlled better than those in PCCs (Table 2). Most patients on lipid-lowering drugs achieved the treatment goal of LDL-cholesterol <120 mg/dl recommended by the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (Table 2).

Discussion

We investigated the medical performance of diabetic patients over a period of 12 years and found that glycemic control improved both in PCCs and hospitals in Japan. Although the mean HbA1c level for patients treated in PCCs was significantly lower than that for those treated in hospitals, the difference was small. In addition, there was little difference in trends in diabetes treatment. The only difference was that patients treated in hospitals used insulin more often than those in PCCs. Examination of diabetic complications were performed more frequently in 2012 than in 2000 and 2006, but was still insufficient. Control of blood pressure improved over time but did not achieve the target range by 2012. Control of lipids improved.

The mean HbA1c levels did not change between 2000 and 2006 but had improved by 2012. According to the Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study (JDDM), a large, cross-sectional study of diabetes clinical data in Japan, mean HbA1c level has been declining since 2008 [9]. Our results corresponded with these findings, although JDDM was a study of diabetologists only. Several probable reasons exist for the recent improvement of glycemic control in Japan. One is that the number of patients treated for diabetes has increased. According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, the proportion of patients who have never been treated has been decreasing, and the proportion of probable diabetic patients treated continuously has been increasing—up to 65.2 % in the latest data—with a 20 % increase from 15 years previously [10]. These findings suggest the need to publicize treatment for diabetes, which might contribute to improvements in glycemic control. Also, it is possible that advances in diabetes treatment played a role, as new diabetic drugs have been developed in recent years. However, there also may be a possibility that the number of mild diabetic patients has increased due to increased public awareness of diabetes in Japan.

Regarding differences between PCCs and hospitals, over the 12 years, mean HbA1c levels for patients treated in PCCs were significantly lower than for those treated in hospitals. A large cross-sectional survey in Japan showed similar results [11]. In other countries, patients treated by GPs also had lower HbA1c levels than those treated by diabetologists [12–14]. In Italy, glycemic control between GPs and diabetologists did not differ [15], but when the same population was limited to HbA1c > 8 %, patients in the GP group had better control than those in the diabetologists group [16]. The review that summarized these studies indicated that the magnitude of difference between GP and specialist care is inconsequential [17]. Most studies were cross-sectional; our study was also based on cross-sectional data, but interestingly, our study showed that the same trend was observed over the 12-year period. In Japan, patients who do not achieve glycemic targets with treatment in PCCs are referred to hospitals. When they are treated and glycemic control improves in hospitals, they come back to their original PCC. This cooperation between PCCs and hospitals might be one reason why the mean HbA1c levels of patients treated in hospitals was difficult to improve. It is not enough to provide sufficient treatment for all diabetic patients using diabetologists alone. Closer cooperation between PCCs and hospitals is needed to implement better quality care for diabetic patients.

In terms of trends in diabetic treatment modalities, JDDM reported that the proportion of patients on diet and exercise only has decreased and the use of OHA (the most commonly used treatment) has slightly increased; furthermore, the use of insulin only has decreased and OHA and insulin together has increased [9]. This pattern of treatment modalities resembles our results. According to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [18, 19], trends are almost the same as those in the current study, although the proportions of patients treated with OHA and both OHA and insulin were higher in the US study than in ours. It is noteworthy that the proportion of patients treated with a combination therapy of OHA and insulin increased substantially by approximately three fold over our 12-year study. We have no information about kinds of OHA and insulin in this study; however, we presume two reasons for the increase. The first is that basal long-acting insulin analogs became available in 2001. It has been reported that basal-supported orally administered therapy is popular, and many patients receive the combination of insulin analogs and OHA in Japan [11]. In a consensus statement for the medical management of type 2 diabetes, basal insulin is one of the recommended choices as a second-line agent added to metformin [20]. The second reason is that new medicines in the form of incretin-related drugs have been available since 2009. In particular, the glucose-lowering efficacy of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors is greater in Asian patients than in Caucasian patients [21]. In Japan, the use of DPP-4 inhibitors has remarkably increased both for monotherapy and combination therapy [9]. As first-line treatment, DPP-4 inhibitors might begin being used earlier than before, and so the proportion of patients treated with diet and exercise only might decline. These changes due to DPP-4 inhibitors are likely to be one of the reasons for the improvement of glycemic control.

The proportion of the patients treated with insulin or combination therapy with OHA and insulin was higher in the hospitals group than the PCCs group. Other studies have also shown that insulin is used more often by diabetologists than by GPs [2, 12, 22]. The reason suggested is that diabetologists treat patients with more severe diabetes and prescribe more insulin than GPs. The trend in glycemic control by treatment was almost the same in PCCs and hospitals, although mean HbA1c levels were sustained between 2000 and 2006 in hospitals. Mean HbA1c levels were higher in increasing order of diet and exercise only, OHA, insulin, and OHA with insulin. This trend agrees with that in a previous report [23].

Patients in whom microalbuminuria was assessed increased but remained at <40 %. The proportion of patients who received microalbuminuria assessment was higher in hospitals than in PCCs and increased over time. Half of all patients had retinal screening, but the rate rose only 5 % between 2012 and 2000; the proportion of patients in hospitals was higher than that in PCCs over time. In reports from other countries, findings are not consistent concerning whether the examination rate of microalbuminuria and retinal screening is higher in PCCs or hospitals [13, 15] because every country has a different system of hospital and PCC cooperation. In reports from Japan, both screenings were more frequently performed by diabetologists than by GPs [24–26]. Many diabetologists belong to hospitals, and the ophthalmology department is established in the same hospital as the internal medicine department in Japan. It is therefore easy for patients treated in the hospital or by diabetologists to undergo retinal screening.

Two kinds of notebooks for the cooperation of physicians and ophthalmologists were issued by the Japanese Society of Ophthalmic Diabetology (JSOD) in 2002 and by the Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care in 2010. As a result, physicians and patients have been recognizing the necessity of retinal screening. The JSOD reported that utilization rates of the notebook rose for the first 7 years after notebook publication but decreased thereafter [27]. Our result is in accordance with these findings and indicates that it is necessary to promote the cooperation of physicians and ophthalmologists, especially for PCC patients.

Previous studies from Japan and elsewhere have reported that microalbuminuria is examined more frequently in patients treated by diabetologists than those treated by GPs [15, 24–26]. Our results are consistent with these reports [15, 24, 26], and the proportion examined was ≤50 % even in the hospitals group, in which most patients were treated by diabetologists. The JDDM (in which participants were treated by diabetologists) reported that 40 % of participants did not undergo measurement of microalbuminuria [28]. To conform to the recommendation, we appeal to the importance of this examination in daily practice.

Our results suggest that it is difficult to achieve target blood pressure both in PCCs and hospitals. The Japan Diabetes Complications Study (JDCS), a prospective study of type 2 diabetic patients treated by diabetologists in Japan, reported that the proportion of patients whose blood pressure was ≥140/90 mmHg was approximately 40 % and those with blood pressure <130/85 mmHg was <40 % [29]. JDDM reported that the proportion of patients <130/80 mmHg was 50 % [23]. According to a report from Europe, the proportion of patients <140/80 mmHg was 29 %, and only 23 % of those with medication for hypertension achieved <140/80 mmHg [30]. Further effort is required toward control of blood pressure in diabetic patients.

Control of LDL-cholesterol was better than that of blood pressure: in 50 % of patients, LDL-cholesterol was ≤120 mg/dl in the JDCS [29]. Other studies reported that LDL-cholesterol was ≤130 mg/dl in 66 % [30] and about 50 % of patients [31]. Currently, it seems to be easier than before to reach the target of LDL-cholesterol by the use of strong statins. Our result in 2012 showed that most patients on lipid-lowering drugs had LDL-cholesterol levels <120 mg/dl.

This study has several limitations. First, patients with types 1 and 2 diabetes were mixed; most probably, a higher number had type 2 diabetes because the incidence of type 1 diabetes is very low in Japan (1.5/105) [32]. However, most patients with type 1 diabetes might have been treated in hospitals. This might be one of the reasons why patients treated in hospitals used more insulin than those in PCCs. Second, our study potentially has the possibility of selection bias. PCCs and hospitals that have a particular interest in diabetes care may have participated more frequently. The response rate was unclear in this study, although we presume that most medical institutes that provide medical care to diabetic patients participated. Third, HbA1c measurement was carried out at each clinic or hospital and was not centralized. However, in Japan, the Glycohemoglobin Standardization Committee evaluated the interlaboratory variation of glycohemoglobin (GHb) values and had already reported that the interlaboratory difference in GHb measurement was reduced to a clinically acceptable level [33]. Finally, levels of LDL-cholesterol were calculated by the Friedewald formula; however, data in 2012 were combined with data taken from direct measurement. Directly measured LDL-cholesterol has not been standardized sufficiently in Japan [34], but it has been included in the national health checkup program since 2008 [35]. LDL-cholesterol measurements obtained by the two methods were highly correlated (r = 0.904, P < 0.0001) in this study.

In conclusion, this study showed that glycemic control has been improving in Japan. However, examination of diabetic complications and control of blood pressure are still insufficient. Further effort and closer cooperation between PCCs and hospitals is needed to provide appropriate medical care for all diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the Shiga Medical Association for their participation in this study. Members of the Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey Group: Atsunori Kashiwagi (Department of Medicine, Shiga University of Medical Science), Masayuki Shigenaga (Shigenaga Clinic), Yuichi Orita (Orita Clinic), Tsuyoshi Otaka (Otaka Clinic), Nobuisa Mizuno, Hirohumi Hukumoto (Department of Medicine, Shiga Medical Center for Adults), Takamasa Miura (Miura Clinic), Yasuhiro Nishida (Department of Ophthalmology, Shiga University of Medical Science), Naoyuki Takashima, Hirotsugu Ueshima (Department of Health Science, Shiga University of Medical Science), Katsuhito Yoshitoku (Yoshitoku Clinic), Hideki Yano (Department of Medicine, Hikone Municipal Hospital), Makoto Konishi (Konishi Clinic), Hideki Noda, Masataka Nishimura (Department of Medicine, Nagahama City Hospital), Kenji Kamiuchi (Department of Medicine, Otsu Municipal Hospital), Masanori Iwanishi (Department of Medicine, Kusatsu General Hospital), Hideo Kawamura (Kawamura Clinic), Naoya Ochiai (Miyaji Clinic), Yukimasa Shimosaka (Shimosaka Clinic), Jun Morita (Morita Dental Clinic). Writing committee: Itsuko Miyazawa, Hiroshi Maegawa (Department of Medicine, Shiga University of Medical Science), Aya Kadota, Katsuyuki Miura (Department of Public Health, Center for Epidemiologic Research in Asia, Shiga University of Medical Science), Motozumi Okamoto (Japanese Red Cross Otsu Hospital), Atsuo Ohnishi (Ohnishi Clinic).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Human rights

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, “Personal Information Protection Law” of Japan, “Ethical Guidelines in Epidemiological Research” compiled the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by a committee including experts in ethical matters and the board of the Shiga Medical Association and by the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (Shiga University of Medical Science).

Contributor Information

Itsuko Miyazawa, Phone: +81-77-548-2222, Email: shimojo@belle.shiga-med.ac.jp.

For the Shiga Diabetes Clinical Survey Group:

Atsunori Kashiwagi, Masayuki Shigenaga, Yuichi Orita, Tsuyoshi Otaka, Nobuisa Mizuno, Hirohumi Hukumoto, Takamasa Miura, Yasuhiro Nishida, Naoyuki Takashima, Hirotsugu Ueshima, Katsuhito Yoshitoku, Hideki Yano, Makoto Konishi, Hideki Noda, Masataka Nishimura, Kenji Kamiuchi, Masanori Iwanishi, Hideo Kawamura, Naoya Ochiai, Yukimasa Shimosaka, and Jun Morita

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF DIABETES ATLAS. 6th ed.

- 2.Arai K, Hirao K, Matsuba I, Takai M, Matoba K, Takeda H, et al. The status of glycemic control by general practitioners and specialists for diabetes in Japan: a cross-sectional survey of 15,652 patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;83(3):397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. 2010. Population census of Japan. http://www.stat.go.jp/english/index.htm. Accessed 19 Aug 2015.

- 4.Statistics Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Survey of Medical Institutuions. 2000, 2006 and 2012. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/79-1.html. Accessed 14 Oct 2015.

- 5.Atsunori K, Masato K, Eiichi A, Yoshitomo O, Toshiaki H, Hiroshi I, et al. Committee on the Standardization of Diabetes Mellitus-Related Laboratory Testing of Japan Diabetes Society. International clinical harmonization of glycated hemoglobin in Japan: From Japan Diabetes Society to National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program values. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3(1):39–40. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansson L, Hedner T, Himmelmann A. The 1999 WHO-ISH Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension–new targets, new treatment and a comprehensive approach to total cardiovascular risk reduction. Blood Press Suppl. 1999;1:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treatment objectives and control indicators, Treatment Guide for Diabetes 2012–2013, Edited by Japan Diabetes Society: Bunkodo.

- 8.Evidence-based Practice Guideline for the Treatmen for Diabetes in Japan 2013, Japan Diabetes Society: Nankodou.

- 9.Oishi M, Yamazaki K, Okuguchi F, Sugimoto H, Kanatsuka A, Kashiwagi A. Changes in oral antidiabetic prescriptions and improved glycemic control during the years 2002–2011 in Japan (JDDM32) J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5(5):581–587. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Welfare J. Report of national survey of Diabetes; 2012.

- 11.Kanatsuka A, Sato Y, Kawai K, Hirao K, Kobayashi M, Kashiwagi A. Evaluation of insulin regimens as an effective option for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a propensity score-matched cohort study across Japan (JDDM31) J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5(5):539–547. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang ES, Gleason S, Gaudette R, Cagliero E, Murphy-Sheehy P, Nathan DM, et al. Health care resource utilization associated with a diabetes center and a general medicine clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail H, Wright J, Rhodes P, Scally A. Quality of care in diabetic patients attending routine primary care clinics compared with those attending GP specialist clinics. Diabet Med. 2006;23(8):851–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah BR, Hux JE, Laupacis A, Mdcm BZ, Austin PC, van Walraven C. Diabetic patients with prior specialist care have better glycaemic control than those with prior primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(6):568–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Berardis G, Pellegrini F, Franciosi M, Belfiglio M, Di Nardo B, Greenfield S, et al. Quality of care and outcomes in type 2 diabetic patients: a comparison between general practice and diabetes clinics. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):398–406. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah BR, Hux JE, Laupacis A, Zinman B, van Walraven C. Clinical inertia in response to inadequate glycemic control: do specialists differ from primary care physicians? Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):600–606. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Post PN, Wittenberg J, Burgers JS. Do specialized centers and specialists produce better outcomes for patients with chronic diseases than primary care generalists? A systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care: J Int Soc Qual Health Care/ISQua. 2009;21(6):387–396. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzp039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Diabtes Statistics Report, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014StatisticsReport.html. Accessed 19 Aug 2015.

- 19.Number (in Millions) of Adults with Diabetes by Diabtes Medication Status, United Staes, 1997–2011. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/meduse/fig1.htm. Accessed 19 Aug 2015.

- 20.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai X, Han X, Luo Y, Ji L. Efficacy of dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitors and impact on beta-cell function in Asian and Caucasian type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes. 2015;7(3):347–359. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arai K, Takai M, Hirao K, Matsuba I, Matoba K, Takeda H, et al. Present status of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes treated by general practitioners and diabetes specialists in Japan: third report of a cross-sectional survey of 15,652 patients. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3(4):396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi M, Yamazaki K, Hirao K, Oishi M, Kanatsuka A, Yamauchi M, et al. The status of diabetes control and antidiabetic drug therapy in Japan—a cross-sectional survey of 17,000 patients with diabetes mellitus (JDDM 1) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;73(2):198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidaka H, Furusawa S, Tsujinaka K, Yamasaki Y. Quality of care provided to diabetic patients—Analysis of examination frequency of metabolic states and complication by Health insurance claimes for medical care and questionnaires to employees of electronics company. J Jpn Diabetes Soc. 2001;44(12):919–925. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanatsuka A, Mimura M, Sinomiya M, Hashimoto N. Survey of diabetic clinics in Chiba prefecture performed by diabetologists and general physicians. J Jpn Diabetes Soc. 2012;55(9):671–680. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hidaka H, Tokumoto K, Hori Y, Homma S. Prescription and quality of diabetes care provided by specialists and general physicians in Japan—an analysis of insurance claim and health checkup data. J Jpn Diabetes Soc. 2014;57(10):774–782. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohno A, Awane N, Kaji A, Kaji K. Change in questionnaire survey results among Tama area ophthalmological notebook of diabetics (The second report) Prog Med. 2014;34:1657–1663. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yokoyama H, Kawai K, Kobayashi M. Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study G. Microalbuminuria is common in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients: a nationwide survey from the Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group (JDDM 10) Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):989–992. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sone H, Mizuno S, Fujii H, Yoshimura Y, Yamasaki Y, Ishibashi S, et al. Is the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome useful for predicting cardiovascular disease in asian diabetic patients? Analysis from the Japan Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(6):1463–1471. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charpentier G, Genes N, Vaur L, Amar J, Clerson P, Cambou JP, et al. Control of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide French survey. Diabetes Metabol. 2003;29(2 Pt 1):152–158. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comaschi M, Coscelli C, Cucinotta D, Malini P, Manzato E, Nicolucci A. Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic subjects attending outpatient clinics in Italy: the SFIDA (survey of risk factors in Italian diabetic subjects by AMD) study. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis: NMCD. 2005;15(3):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kida K, Mimura G, Ito T, Murakami K, Ashkenazi I, Laron Z. Incidence of Type 1 diabetes mellitus in children aged 0–14 in Japan, 1986–1990, including an analysis for seasonality of onset and month of birth: JDS study. The Data Committee for Childhood Diabetes of the Japan Diabetes Society (JDS) Diabet Med. 2000;17(1):59–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shima K, Endo J, Oimomi M, Omori Y. Interlaboratory difference in GHb measurement in Japan—the Fifth Report of the GHb Stanardization Committee, the Japan Diabetes Society. J Jpn Diabetes Soc. 1998;41(4):317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura M, Koyama I, Iso H, Sato S, Okazaki M, Kayamori Y, et al. Ten-year evaluation of homogeneous low-density lipoprotein cholesterol methods developed by Japanese manufacturers. Application of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Cholesterol Reference Method Laboratory Network lipid standardization protocol. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17(12):1275–1281. doi: 10.5551/jat.5470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura M, Sato S, Shimamoto T, Konishi M, Yoshiike N. Establishment of long-term monitoring system for blood chemistry data by the national health and nutrition survey in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2008;15(5):244–249. doi: 10.5551/jat.E575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]