Abstract

Background

We assessed the prospective association between baseline serum uric acid (SUA) concentrations and consequent risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression in type 2 diabetes patients.

Methods

Longitudinal data from a Japanese diabetes registry including 3454 type 2 diabetes patients were obtained. To assess the independent correlations between SUA and rapid CKD progression [i.e., 30 % reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over 2 years], participants were divided into five groups based on SUA levels: <5.0, ≥5.0–6.0, ≥6.0–7.0, ≥7.0–8.0, and ≥8.0 mg/dl. Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for potential confounders was used for analysis.

Results

After 2 years, rapid CKD progression was recognized in 169 patients (4.89 %) who showed longer duration of type 2 diabetes (15.5 vs. 13.5 years, p = 0.005); higher systolic blood pressure (142.0 vs. 138.3 mmHg, p = 0.016), SUA (6.15 vs. 5.32 mg/dl, p < 0.001), and urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (1127.4 vs. 184.7 mg/gCr, p < 0.001); and lower diastolic blood pressure (69.7 vs. 72.8 mmHg, p = 0.003). Multivariate ratios for rapid CKD progression were 1.19 (p = 0.371), 1.02 (p = 0.937), 1.18 (p = 0.625), and 3.04 (p = 0.004), respectively, for the first, third, fourth, and fifth serum UA range groups; a second group was used as a reference.

Conclusions

Higher SUA levels, independent of possible confounders, were associated with rapid eGFR decline and CKD progression in type 2 diabetes patients. SUA may be a useful biomarker for predicting future risk of rapid diabetic CKD progression.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Uric acid, Epidemiology, Cohort, Human, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

As shown by epidemiological studies, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has significantly increased worldwide, which has resulted in an increased burden on individuals and health care systems [1]. Diabetic nephropathy is a common complication of diabetes and the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in developed countries [2]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide public health issue, with increasing prevalence, poor outcomes, and high treatment costs [3]. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) for evaluating changes in kidney function is the most widely used parameter in clinical practice. However, the GFR course is complex and heterogeneous in type 2 diabetes and primarily depends on individual, ethnic, and disease-specific conditions [4–8]. An understanding of the clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with the progression of diabetic nephropathy or CKD in patients with diabetes would be useful to improve the therapeutic strategies for primary prevention of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and to preserve kidney function.

Uric acid (UA) is the end product of purine metabolism in humans, and approximately 70 % of UA is eliminated by urinary excretion. Hyperuricemia is a frequent complication of CKD and coexists with other risk factors for CKD, such as hypertension and metabolic syndrome [9]. In addition, hyperuricemia may have a mechanistic role in the incidence and progression of renal functional decline and probably has a causal role in hypertension and vascular disease [10, 11]. Evidence that hyperuricemia is an independent risk factor for CKD in patients with diabetes has been increasing recently [12]. In patients with type 1 diabetes, elevated SUA has been found to be associated with the risk of developing proteinuria or decline in renal function [13]. Some recent research showed that elevated SUA levels have been associated with incidence of CKD or decline of renal function in type 2 diabetes patients [14, 15]. However, these studies did not focus on rapid decline of renal function leading to ESRD, were done in a small-sized, retrospective design, or included those with already advanced diabetic renal disease. The most recent study showed hyperuricemia was associated with the risk of CKD in Caucasian patients with type 2 diabetes [16].

The present study aimed to prospectively determine the association between baseline SUA concentration and the consequent risk of rapid progression of CKD over a 2-year follow-up in a cohort of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes including those with relatively preserved renal function from a large-scale single center registry.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patient data were derived from the first-year survey of a diabetes registry at Tenri Hospital, a regional tertiary-care teaching hospital in Japan. The details of this registry can be found elsewhere [17–23]. In brief, this was a cohort study aimed at evaluating the cross-sectional and prospective association between psycho-socio-economic factors, biomarkers, and the incidences of micro- and macrovascular complications in patients with diabetes. The registry recruited patients diagnosed as having diabetes who had visited the outpatient clinic of our hospital between October 2009 and December 2010. We conducted the survey from January to December in 2011, 2012, and 2013. We excluded patients with prediabetes diagnosed by an oral glucose tolerance test, gestational diabetes, type 1 diabetes, or diabetes induced by steroid use or other endocrine diseases, and we eventually used data of patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. At registration, the attending physician confirmed the diagnosis according to the Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Diabetes Mellitus by the Japan Diabetes Society. For the analysis, we included only patients whose baseline SUA data and follow-up eGFR data were available. The Ethics Committee of Tenri Hospital approved this study, and written informed consent was obtained from every participant.

Data collection

In the survey, patients underwent a routine medical history inquiry, physical examination, and laboratory tests. Demographics, including age, sex, height, body weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (dBP), smoking or alcoholic status, and medical history, which included micro- and macrovascular complications, and treatment modalities, which included hypertension medication and anti-hyperuricemia medication, were collected. Laboratory tests included evaluation of HbA1c levels, lipid profiles, serum creatinine, UA levels, and urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (UACR) from a spot urine sample. HbA1c levels were expressed in accordance with the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program as recommended by the Japanese Diabetes Society [24] and in IFCC units. The GFR was estimated using an equation proposed by the Japanese Society of Nephrology [25]: eGFR [(ml/min/1.73 m2) = 194 × Cr−1.094 × age−0.287(×0.739 for female patients].

Outcomes

A decline in eGFR resulting in doubling of the serum creatinine concentration has been used as the standard indicator of CKD progression, but lesser declines have occurred more commonly and have been strongly and consistently associated with the risks of ESRD and mortality, which supports the consideration of lesser declines in the eGFR (such as a 30 % reduction over 2 years) as a surrogate end point for CKD progression [26]. Therefore, we evaluated rapid progression of CKD defined as a ≥30 % reduction in eGFR over 2 years as an outcome of this analysis.

SUA assay

Technicians blinded to the patients’ clinical data collected a random blood sample on the day of the outpatient clinic visit before the patients answered a self-administered survey. Then, technicians performed the test for UA using separated serum. SUA was estimated by the Uricase/POD and end-point assay method.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile ranges for variables with non-normal distributions. Intergroup differences between the SUA range groups were evaluated using the nonparametric test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A t test was used to compare continuous variables between the two groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine categorical variables. The association between SUA range groups and outcomes was analyzed using the Cox proportional hazards model considering clustering within the attending physician. To evaluate the the association of SUA with a consequent risk of rapid progression of CKD in diabetes patients with preserved renal function, we performed the analysis by excluding patients with eGFR less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 at baseline. Person-time was calculated from the baseline date to the day the outcome was confirmed, or the end of follow-up, whichever occurred first. The hazard ratio [HR; 95 % confidence intervals (CIs)] was estimated for the outcome by using the second SUA range group as a reference category. Three statistical models were used: a crude model; an age- and sex-adjusted model; and a model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol drinking, systolic blood pressure (sBP), dBP, HDL, LDL, triglyceride, serum creatinine, eGFR, UACR, HbA1c levels, duration of diabetes, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor use, angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) use, diuretic drug use, anti-hyperuricemia drug use, and history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). We selected these covariates because they are known or considered to be associated with SUA levels and CKD. All p values were two sided. p values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE version 12 (Stata Corp.; College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

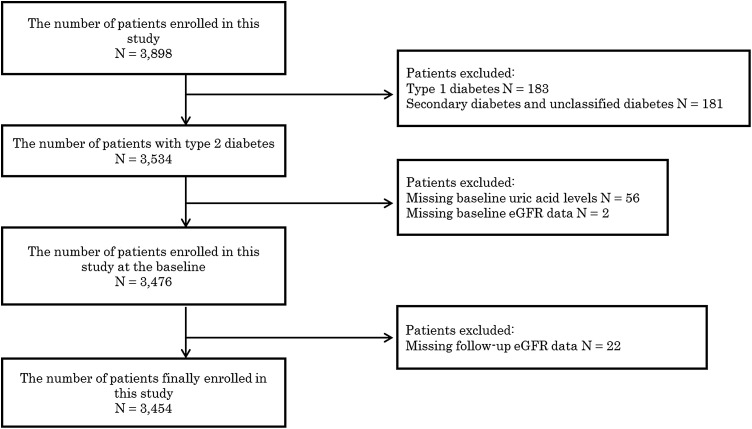

In 2009, 3898 patients were enrolled in the study [mean age (SD), 64.5 (11.7); 39.6 % female; 4.7 % type 1 diabetes; 90.7 % type 2 diabetes], and 3534 of those had type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, 56 patients were excluded because of missing UA levels, two patients because of missing baseline eGFR data, and 22 patients because of missing follow-up eGFR data. The remaining 3454 patients were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A flow chart to describe inclusion patients

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and laboratory data of patients in the five SUA range groups: <5.0, ≥5.0–6.0, ≥6.0–7.0, ≥7.0–8.0, and ≥8.0 mg/dl (<297, ≥297–<357, ≥357–416, ≥416–476, and ≥476 μmol/l). Overall, the mean age, HbA1c level, and BMI were 65.1 years, 7.50 % (56.6 mmol/mol), and 24.6 kg/m2, respectively. Patients with higher UA levels tended to be male (p < 0.001) and have higher sBP (p < 0.001), higher BMI (p < 0.001), lower HDL levels (p < 0.001), higher triglyceride levels (p < 0.001), higher creatinine levels (p < 0.001), lower eGFR (p < 0.001), higher UACR (p < 0.001), lower HbA1c (p < 0.001), and lower never-smoking status (p < 0.001) in addition to having a greater likelihood of using ARB (p < 0.001), ACE inhibitors (p < 0.001), diuretic drugs (p < 0.001), anti-hyperuricemia drugs (p < 0.001), and of history of CVD (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Participant baseline characteristics for each of the total serum uric acid concentration groups

| All subjects (n = 3454) | Serum uric acid groups | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 1437) | Group 2 (n = 910) | Group 3 (n = 633) | Group 4 (n = 305) | Group 5 (n = 169) | |||

| Serum uric acid, mg/dl | |||||||

| Mean ± (SD) | 5.36 (1.49) | 4.02 (0.68) | 5.43 (0.28) | 6.40 (0.29) | 7.35 (0.27) | 8.96 (0.96) | |

| Range | (−4.9) | (5.0–5.9) | (6.0–6.9) | (7.0–7.9) | (8.0–) | ||

| Age, years | 65.1 (11.1) | 65.1 (10.9) | 64.8 (11.3) | 65.3 (11.4) | 65.4 (10.7) | 66.1 (12.3) | 0.218 |

| Female, % | 38.2 | 52.6 | 33.9 | 24.6 | 18.0 | 24.44 | <0.001 |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus, years | 13.6 (9.9) | 14.0 (10.0) | 13.1 (9.6) | 13.3 (9.9) | 13.4 (10.2) | 14.4 (10.4) | 0.382 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.6 (3.9) | 23.9 (3.8) | 24.8 (3.9) | 25.3 (4.0) | 25.4 (3.8) | 25.3 (4.0) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 138.4 (19.0) | 137.1 (18.7) | 138.7 (18.4) | 138.8 (18.8) | 141.0 (19.1) | 142.6 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 72.7 (12.2) | 72.0 (11.7) | 73.7 (12.4) | 72.5 (11.7) | 73.0 (13.5) | 72.9 (15.0) | 0.304 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 58.2 (16.1) | 61.7 (16.1) | 58.0 (16.0) | 54.8 (15.6) | 53.7 (14.5) | 50.7 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 112.5 (30.2) | 113.1 (29.6) | 112.8 (30.1) | 112.6 (30.9) | 112.0 (30.5) | 106.8 (32.7) | 0.056 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dla | 129 (89–186) | 115 (81–163) | 132 (90–186) | 143 (103–205) | 152 (105–225) | 153 (107–238) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.92 (0.94) | 0.72 (0.63) | 0.86 (0.88) | 0.97 (0.75) | 1.29 (1.43) | 1.87 (1.89) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 74.1 (24.9) | 83.4 (23.4) | 74.4 (20.7) | 67.3 (22.1) | 59.5 (23.4) | 44.9 (27.0) | <0.001 |

| Urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, mg/gCra | 29.6 (14.4–101.0) | 24.8 (14.1–59.6) | 26.6 (13.1–83.2) | 46.1 (15.5–170.2) | 47.8 (16.6–206.5) | 113.0 (29.7–747.7) | <0.001 |

| ALT, IU/l | 24.0 (17.5) | 22.8 (16.9) | 24.6 (17.7) | 26.3 (20.0) | 24.1 (15.6) | 21.8 (13.3) | 0.010 |

| AST, IU/l | 26.7 (15.7) | 25.7 (16.3) | 26.2 (12.5) | 28.9 (17.6) | 28.0 (16.1) | 26.6 (16.5) | <0.001 |

| Gamma GTP, IU/l | 44.4 (67.9) | 38.2 (60.1) | 44.0 (55.7) | 48.8 (75.1) | 61.4 (108.0) | 52.0 (61.6) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c | |||||||

| NGSP, % | 7.50 (1.16) | 7.70 (1.24) | 7.48 (1.10) | 7.32 (1.05) | 7.28 (1.06) | 7.10 (1.08) | <0.001 |

| IFCC, mmol/mol | 56.6 (11.9) | 58.6 (12.7) | 56.3 (11.3) | 54.7 (10.7) | 54.3 (10.9) | 52.5 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Smoking, % | |||||||

| Never | 42.7 | 53.0 | 40.3 | 32.5 | 29.2 | 29.4 | <0.001 |

| Past | 38.2 | 29.0 | 39.3 | 47.4 | 51.5 | 51.6 | <0.001 |

| Current | 19.2 | 18.0 | 20.4 | 20.1 | 19.3 | 19.0 | 0.459 |

| ACE inhibitor use, % | 7.1 | 5.3 | 7 | 8.4 | 10.5 | 12.4 | <0.001 |

| ARB use, % | 32.0 | 22.9 | 32.3 | 38.9 | 46.2 | 57.4 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic drug use, % | 14.7 | 6.6 | 12.5 | 19.1 | 31.2 | 47.9 | <0.001 |

| Anti-hyperuricemic drug use, % | 6.3 | 2.2 | 6.2 | 8.5 | 13.8 | 20.7 | <0.001 |

| History of cardiovascular disease, % | 23.8 | 20.2 | 23.1 | 28.4 | 30.5 | 27.8 | <0.001 |

Conversion factors for units: uric acid in mg/dl to μmol/l, ×59.48; HDL in mg/dl to mmol/l, ×0.02586; LDL in mg/dl to mmol/l, ×0.02586; triglyceride in mg/dl to mmol/l, ×0.01129; creatinine in mg/dl to μmol/l, ×88.4

Data are means ± (SD) unless otherwise indicated

aMedian and interquartile range

The numeric results of a comparison of factors between patients without and with rapid decline of eGFR are presented in Table 2. We found significant differences between the two groups in sex, duration of DM history, sBP, dBP, SUA concentration, HDL levels, serum creatinine, eGFR, UACR, never smoking status, ACE inhibitor use, ARB use, diuretic drug use, and anti-hyperuricemia drug use. The comparison between patients with and without rapid progression of CKD showed no significant differences in BMI, LDL, triglycerides, HbA1c, and history of CVD.

Table 2.

Factors associated with rapid progression of CKD in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and 2 years of follow-up

| Variables | Without rapid progression of CKD (n = 3285) | With rapid progression of CKD (n = 169) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.1 (11.2) | 66.1 (11.0) | 0.125 |

| Female, % | 38.6 | 29.6 | 0.019 |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus | 13.5 (9.8) | 15.5 (11.1) | 0.005 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.6 (3.9) | 24.5 (3.9) | 0.438 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 138.3 (18.9) | 142.0 (22.0) | 0.016 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 72.8 (12.1) | 69.7 (13.7) | 0.003 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 5.32 (1.44) | 6.15 (1.98) | <0.001 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 58.4 (16.1) | 55.5 (16.1) | 0.012 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 112.7 (30.0) | 109.8 (35.5) | 0.116 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dla | 129 (89–185) | 136 (101–206) | 0.057 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.88 (0.91) | 1.44 (1.39) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 74.7 (23.8) | 63.2 (38.9) | <0.001 |

| Urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, mg/gCra | 28.5 (14.2–91.1) | 156.4 (33.2–1347.3) | <0.001 |

| ALT, IU/l | 24.0 (17.3) | 24.0 (20.7) | 0.487 |

| AST, IU/l | 26.5 (15.5) | 29.0 (18.6) | 0.024 |

| Gamma GTP, IU/l | 43.7 (66.9) | 58.0 (84.4) | 0.004 |

| HbA1c | |||

| NGSP, % | 7.51 (1.15) | 7.48 (1.44) | 0.386 |

| IFCC, mmol/mol | 56.6 (11.7) | 56.3 (14.7) | 0.386 |

| Smoking, % | |||

| Never | 43.2 | 32.0 | 0.005 |

| Past | 37.7 | 47.3 | 0.039 |

| Current | 19.2 | 20.7 | 0.748 |

| ACE inhibitor use, % | 7.1 | 7.7 | 0.756 |

| ARB use, % | 31.2 | 48.5 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic drug use, % | 13.9 | 28.4 | <0.001 |

| Anti-hyperuricemic drug use, % | 5.9 | 14.8 | <0.001 |

| History of cardiovascular disease, % | 23.6 | 26.6 | 0.367 |

Conversion factors for units: uric acid in mg/dl to μmol/l, ×59.48; HDL in mg/dl to mmol/l, ×0.02586; LDL in mg/dl to mmol/l, ×0.02586; triglyceride in mg/dl to mmol/l, ×0.01129; creatinine in mg/dl to μmol/l, ×88.4

Data are means ± (SD) unless otherwise indicated

aMedian and interquartile range

In a cohort, over a median follow-up of 497 days, we observed 169 patients who had rapid progression of CKD [>30 % reduction of eGFR over 2 years; incidence ratio = 36.3/1000 person-years (95 % CI 31.2–42.2), Table 3]. The HRs for the association between SUA range groups and rapid progression of CKD are shown in Table 4. In all three models (the crude model, age- and sex-adjusted model, and multivariable-adjusted model), we observed a significant association between baseline SUA range groups and the consequent risk of rapid progression of CKD. The HRs for rapid progression of CKD for the first, third, fourth, and fifth range groups compared with the second group of SUA range used as a reference were 1.03 (95 % CI 0.74–1.43; p = 0.872), 1.32 (95 % CI 0.82–2.11; p = 0.253), 2.18 (95 % CI 1.10–4.31; p = 0.029), and 6.35 (95 % CI 4.17–9.68; p < 0.001), respectively, for the crude model. Adjusting for age did not influence the results. Adjusting for the multivariable attenuated the association; the multivariable adjusted HRs were 1.19 (95 % CI 0.81–1.75; p = 0.371), 1.02 (95 % CI 0.56–1.89; p = 0.937), 1.18 (95 % CI 0.60–2.32; p = 0.625), and 3.04 (95 % CI 1.42–6.48; p = 0.004), respectively, for the first, third, fourth, and fifth range groups compared with the second group of SUA range used as a reference. Furthermore, a similar association between SUA range groups and rapid progression of CKD was also shown in the stratified analysis for the type 2 diabetic patients without CKD (defined as an eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2) and patients without anti-hyperuricemic drug use (Tables 5, 6).

Table 3.

Baseline serum uric acid concentration groups and subsequent risk of rapid progression of CKD

| Serum uric acid groups | Number of subjects | Person-years | Number of outcomes | Incidence ratio (95 % CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 1437 | 1940.0 | 51 | 26.3 (20.0–34.6) |

| Group 2 | 910 | 1236.1 | 33 | 26.7 (19.0–37.6) |

| Group 3 | 633 | 852.5 | 29 | 34.0 (23.7–49.0) |

| Group 4 | 305 | 410.2 | 23 | 56.0 (37.3–84.4) |

| Group 5 | 169 | 219.1 | 33 | 150.6 (107.1–211.8) |

aIncidence rate of outcomes per 1000 person-years

Table 4.

Association between serum uric acid concentration and rapid progression of CKD

| Number of p subjects | Serum uric acid groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 1437) | Group 2 (n = 910) | Group 3 (n = 633) | Group 4 (n = 305) | Group 5 (n = 169) | |

| Uric acid levels, mg/dl | |||||

| Mean ± (SD) | 4.02 (0.68) | 5.43 (0.28) | 6.40 (0.29) | 7.35 (0.27) | 8.96 (0.96) |

| Range | < 4.9 | 5.0–5.9 | 6.0–6.9 | 7.0–7.9 | 8.0 =< |

| Hazard ratio for development (95 % CI) | |||||

| Crude model | 1.03 (0.74–1.43) | Ref. | 1.32 (0.82–2.11) | 2.18 (1.10–4.31) | 6.35 (4.17–9.68) |

| Age- and sex-adjusted model | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) | Ref. | 1.29 (0.81–2.05) | 2.10 (1.08–4.10) | 6.22 (4.09–9.46) |

| Multivariate-adjusted modela | 1.19 (0.81–1.75) | Ref. | 1.02 (0.56–1.89) | 1.18 (0.60–2.32) | 3.04 (1.42–6.48) |

aAdjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking, duration of diabetes mellitus, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use, anti-hyperuricemia drug use, angiotensin II receptor blocker use, diuretic drug use, HbA1c levels, history of cardiovascular disease, and alcohol drinking

Table 5.

Association between serum uric acid concentration and rapid progression of CKD (patients with eGFR ≥60)

| Number of subjects | Serum uric acid groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 1276) | Group 2 (n = 722) | Group 3 (n = 413) | Group 4 (n = 148) | Group 5 (n = 50) | |

| Uric acid levels, mg/dl | |||||

| Mean ± (SD) | 3.99 (0.69) | 5.42 (0.28) | 6.40 (0.28) | 7.32 (0.24) | 8.61 (0.64) |

| Range | < 4.9 | 5.0–5.9 | 6.0–6.9 | 7.0–7.9 | 8.0 =< |

| Hazard ratio for development (95 % CI) | |||||

| Crude model | 1.15 (0.71–1.87) | Ref. | 1.24 (0.58–2.64) | 1.48 (0.34–6.54) | 4.95 (1.79–13.69) |

| Age- and sex-adjusted model | 1.19 (0.70–2.04) | Ref. | 1.23 (0.60–2.51) | 1.46 (0.35–6.18) | 5.08 (1.88–13.75) |

| Multivariate-adjusted modela | 0.69 (0.43–1.12) | Ref. | 1.12 (0.52–2.42) | 1.29 (0.26–6.31) | 3.98 (1.02–15.51) |

aAdjusted for age, sex, body-mass index, smoking, duration of diabetes mellitus, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use, anti-hyperuricemia drug use, angiotensin II receptor blocker use, diuretic drug use, HbA1c levels, history of cardiovascular disease, and alcohol drinking

Table 6.

Association between serum uric acid concentration and rapid progression of CKD (patients without anti-hyperuricemia drug use)

| Number of subjects | Serum uric acid groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 1406) | Group 2 (n = 854) | Group 3 (n = 579) | Group 4 (n = 263) | Group 5 (n = 134) | |

| Uric acid levels, mg/dl | |||||

| Mean ± (SD) | 4.01 (0.68) | 5.42 (0.28) | 6.40 (0.29) | 7.35 (0.27) | 8.90 (0.96) |

| Range | < 4.9 | 5.0–5.9 | 6.0–6.9 | 7.0–7.9 | 8.0 =< |

| Hazard ratio for development (95 % CI) | |||||

| Crude model | 1.01 (0.67–1.51) | Ref. | 1.34 (0.83–2.18) | 1.86 (0.74–4.66) | 5.99 (3.75–9.55) |

| Age- and sex-adjusted model | 1.05 (0.69–1.61) | Ref. | 1.31 (0.82–2.10) | 1.80 (0.74–4.41) | 5.81 (3.65–9.25) |

| Multivariate-adjusted modela | 1.10 (0.67–1.77) | Ref. | 1.03 (0.62–1.72) | 1.11 (0.49–2.55) | 2.71 (1.28–5.71) |

aAdjusted for age, sex, body-mass index, smoking, duration of diabetes mellitus, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, triglyceride, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use, angiotensin II receptor blocker use, diuretic drug use, HbA1c levels, history of cardiovascular disease, and alcohol drinking

Discussion

In our prospective 2-year observational study of a large-scale cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes, we demonstrated that a high SUA level was an independent, specific, and significant predictor of rapid progression of CKD in patients with diabetes. This association was true for men and women regardless of the patient’s eGFR levels or renal function.

Although previous studies suggest that the SUA concentration may be associated with diabetic nephropathy or subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with T2DM [27, 28], the role of UA in patients with type 2 diabetes is still not well studied, particularly in association with declining renal function. Our results were consistent with previous findings. A cohort study that included 1449 type 2 diabetes patients with normal kidney function showed that hyperuricemia seemed to be an independent risk factor for the development of incident CKD [14]; however, this study did not reveal whether UA was associated with a rapid decline of renal function. Another retrospective cohort study including 290 patients with type 2 diabetes showed that elevated SUA levels within the normal range at the onset of overt nephropathy resulted in an increased risk of declining renal function in type 2 diabetes patients [15]. The study was a retrospective, observational, small-scale cohort study conducted at a single diabetes center, and all patients included in this study had already developed diabetic nephropathy at the baseline. A longitudinal study of 13,964 subjects with normal renal function (eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2) and normoalbuminuria showed that a high SUA level was associated with the risk of CKD in Caucasian patients with type 2 diabetes from the database of the Italian Association of Clinical Diabetologists network [16]. This study was a longitudinal large-scale, multiple-center study, but its outcome was onset of CKD, not progression of CKD or rapid decline of GFR. The study showed the incidence of eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 increased in parallel with uric acid quintiles compared with the lowest quintile. In a different way, we showed the prospective association between UA and rapid decline of renal function: a ≥30 % reduction in eGFR over 2 years, with the second SUA range group as a reference category using relatively large-scale of data in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes. As shown in Tables 5 and 6, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has shown that SUA was associated with the subsequent rapid decline of renal function in patients with preserved renal function. In addition, higher SUA levels were also associated with a rapid eGFR decline in the stratified analysis for patients without anti-hyperuricemia drug use (Tables 5, 6). Therefore, this association of SUA levels and rapid eGFR decline was independent of an anti-hyperuricemia drug effect.

SUA and eGFR levels may be related to the state of dehydration. The groups with higher SUA levels had higher percentages of diuretic drug use (Table 1). Table 2 shows a significant difference between patients with and without a rapid decline of eGFR in the percentage of diuretic drug use. However, the association between SUA and rapid decline of eGFR should not be related to diuretic drug use and dehydration since the multivariate-adjusted model in the Cox proportional hazards analysis also adjusted for diuretic drug use.

Since 1993, the Food and Drug Administration has accepted doubling of the serum creatinine value as a surrogate endpoint for CKD progression in clinical trials [29]. Therefore, in clinical trials, adopting a lesser eGFR decline as an alternative endpoint for CKD progression may result in shorter follow-up duration, lower costs, and increased efficiency. Our study found a prospective association between hyperuricemia and progression of diabetic CKD in patients with type 2 diabetes. Several possible mechanisms have been postulated. UA is the final product of purine metabolism and is formed from xanthine by the action of xanthine oxidase. Hyperuricemia by itself may be responsible for such complications through stimulation of the renin–angiotensin system and inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide [30, 31]. A correlation between elevated SUA levels and endothelial dysfunction or renin activity in humans has also been reported [32, 33]. A recent cohort study of 277 patients followed from onset of type 1 diabetes indicated that the UA level, soon after the onset of type 1 diabetes, had a causal role in the risk of later development of diabetic nephropathy [34].

Hyperuricemia is usually defined as an SUA level of ≥7.0 mg/dl (416 µmol/l) [35]. Our results showed that only 13.8 and 20.7 % of patients with hyperuricemia, that is, SUA levels ≥7.0 mg/dl, in the fourth and fifth SUA range groups, respectively, received medication for antihyperuricemia (Table 1). Some researches show that only a minority of patients with gout receive adequate treatment [36, 37], and in the Japanese guidelines for the management of hyperuricemia and gout, a careful approach is taken for the medical treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricemia [38]. This fact may suggest that the treatment of hyperuricemia without symptoms is not sufficiently provided. Several studies in the past few years have evaluated the effect of urate-lowering therapy on renal function. A randomized controlled trial conducted on 113 patients with eGFR values <60 ml/min/1.73 m21 showed that allopurinol decreased the SUA level and had a renoprotective effect. After 24 months in the control group, the eGFR had decreased from 39.5 to 35.9 ml/min/1.73 m2, but increased from 40.8 to 42.2 ml/min/1.73 m2 in the allopurinol group [39]. The post hoc analysis of the reduction of endpoints in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus with the angiotensin II antagonist losartan trial showed that losartan lowered SUA levels compared with placebo treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy, which could contribute to its renoprotective effect [40]. Liu et al. showed that the long-term effective control of SUA levels with allopurinol treatment could decrease urinary albumin excretion and serum creatinine and increase the GFR in 176 patients with T2DM and asymptomatic hyperuricemia [41]. A large-scale prospective intervention study is warranted to assess whether active drug intervention for hyperuricemia patients with diabetes leads to protection of renal function.

In our study, we observed a negative correlation between HbA1c and SUA levels (Table 1). Recent study indicated the relationship between SUA and glucosuria [42]. This study demonstrated that the SUA-lowering can account for the increase in the urinary excretion rate of UA by alteration of UA transport activity in the renal tubules by increased glycosuria. This mechanism may explain the negative correlation between HbA1c and SUA levels observed in our study.

Some limitations were observed in our study. Because this was an epidemiological study, residual confounders may have existed in the association with progression of CKD, and hyperuricemia might have acted as a bystander or biomarker. In addition, data were derived from the registry of a single diabetes center in Japan, thereby raising concerns regarding generalizations derived from the results, particularly for multiethnic populations.

In conclusion, hyperuricemia in type 2 diabetes was associated with an increased risk for rapid decline in eGFR, which in turn is associated with rapid progression of CKD. High SUA levels may be useful for predicting the future risk of progression of diabetic CKD. Further study is required to test whether lowering the SUA may represent an important therapeutic target for mitigating renal failure risk in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to especially thank Yukari Moritsuji, Yuki Fujita, Noriko Nakamura, and Yoko Sakamoto (Department of Endocrinology, Tenri Hospital) for their clerical support. The authors would like to thank Enago (http://www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Appendix

Members of the Diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri Study Group Satoru Tsujii, Hirohito Kuwata, Shintaro Okamura, Yasuaki Hayashino, Miyuki Furuya, Masako Kitatani, (Department of Endocrinology, Tenriyorozu Hospital); Hitoshi Ishii, Tsuyoshi Mashitani (Department of Diabetology, Nara Medical University); Satoshi Matsunaga (Department of Hematology, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Niigata University Faculty of Medicine); Yaeko Kondo, Naotaka Fujita (Department of Diabetes and Clinical Nutrition, Kyoto University); Rei Ueda (Second Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of the Ryukyus); Rie Kurokawa (Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health); Masami Tanaka (Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Keio University School of Medicine).

Conflict of interest

This study was partially supported by the Manpei Suzuki Diabetes Foundation and JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. 25460641); however, they played no role in the design, conduct, data collection, analysis, or results interpretation of the study or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. H. Ishii reports personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., personal fees from Eli Lilly Japan K.K., personal fees from Merck & Co., Inc., personal fees from Astellas Pharma Inc., and personal fees from Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd., outside the submitted work.

Human rights statement and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or a substitute for it was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Footnotes

Members of the Diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri Study Group are listed in the Appendix.

References

- 1.Fenwick E, Rees G, Pesudovs K, et al. Social and emotional impact of diabetic retinopathy: a review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritz E, Orth SR. Nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1127–1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckardt K-U, Coresh J, Devuyst O, et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet. 2013;382:158–169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes-2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hovind P, Rossing P, Tarnow L, Smidt UM, Parving HH. Progression of diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2001;59:702–709. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keane WF, Brenner BM, de Zeeuw D, et al. The risk of developing end-stage renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: the RENAAL study. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1499–1507. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taft JL, Nolan CJ, Yeung SP, Hewitson TD, Martin FI. Clinical and histological correlations of decline in renal function in diabetic patients with proteinuria. Diabetes. 1994;43:1046–1051. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.8.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueda H, Ishimura E, Shoji T, et al. Factors affecting progression of renal failure in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1530–1534. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cirillo P, Sato W, Reungjui S, et al. Uric acid, the metabolic syndrome, and renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:S165–S16810. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feig DI. Uric acid: a novel mediator and marker of risk in chronic kidney disease? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18:526–530. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328330d9d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obermayr RP, Temml C, Gutjahr G, Knechtelsdorfer M, Oberbauer R, Klauser-Braun R. Elevated uric acid increases the risk for kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2407–2413. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagawa T, Kang D-H, Feig D, et al. Unearthing uric acid: an ancient factor with recently found significance in renal and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1722–1725. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ficociello LH, Rosolowsky ET, Niewczas MA, et al. High-normal serum uric acid increases risk of early progressive renal function loss in type 1 diabetes: results of a 6-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1337–1343. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoppini G, Targher G, Chonchol M, et al. Serum uric acid levels and incident chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and preserved kidney function. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:99–104. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka K, Hara S, Hattori M, et al. Role of elevated serum uric acid levels at the onset of overt nephropathy in the risk for renal function decline in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6:98–10416. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Cosmo S, Viazzi F, Pacilli A, et al. AMD-Annals Study Group. Serum uric acid and risk of ckd in type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1921–1929. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03140315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashino Y, Tsujii S, Ishii H. High frequency of non-nocturnal hypoglycemia was associated with poor sleep quality measure by Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index in patients with diabetes receiving insulin therapy: Diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri (DDCRT 4) Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2013;121:628–634. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1355424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashino Y, Mashitani T, Tsujii S, Ishii H. Elevated levels of hs-CRP are associated with high prevalence of depression in japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri (DDCRT 6) Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2459–2465. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashino Y, Okamura S, Matsunaga S, Tsujii S, Ishii H. The association between problem areas in diabetes scale scores and glycemic control is modified by types of diabetes therapy: diabetes distress and care registry in Tenri (DDCRT 2) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mashitani T, Hayashino Y, Okamura S, et al. Diabetes treatment-related quality of life is associated with levels of self-care activities in insulin injection among Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: Diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri (DDCRT 8). Acta Diabetol 2015. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Mashitani T, Hayashino Y, Okamura S, et al. Patient-reported adherence to insulin regimen is associated with glycemic control among Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri (DDCRT 3) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mashitani T, Hayashino Y, Okamura S, Tsujii S, Ishii H. Correlations between serum bilirubin levels and diabetic nephropathy progression among Japanese type 2 diabetic patients: a prospective cohort study [Diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri (DDCRT 5)] Diabetes Care. 2014;37:252–258. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsujii S, Hayashino Y, Ishii H. Diabetes distress, but not depressive symptoms, is associated with glycaemic control among Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: Diabetes Distress and Care Registry at Tenri (DDCRT 1) Diabet Med. 2012;29:1451–1455. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seino Y, Nanjo K, Tajima N, et al. Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2010;1:212–228. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–992. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, et al. Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA. 2014;311:2518–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu C-C, Wu D-A, Wang J-H, Yang W-C, Tseng C-H. Association of C-reactive protein and hyperuricemia with diabetic nephropathy in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Diabetol. 2009;46:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s00592-008-0069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukui M, Tanaka M, Shiraishi E, et al. Serum uric acid is associated with microalbuminuria and subclinical atherosclerosis in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2008;57:625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1456–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corry DB, Eslami P, Yamamoto K, Nyby MD, Makino H, Tuck ML. Uric acid stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and oxidative stress via the vascular renin-angiotensin system. J Hypertens. 2008;26:269–275. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f240bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menè P, Punzo G. Uric acid: bystander or culprit in hypertension and progressive renal disease? J Hypertens. 2008;26:2085–2092. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32830e4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl JMed. 2008;359:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercuro G, Vitale C, Cerquetani E, et al. Effect of hyperuricemia upon endothelial function in patients at increased cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:932–935. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hovind P, Rossing P, Tarnow L. Serum uric acid as a predictor for development of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: an inception cohort study. Diabetes. 2009;58:2–5. doi: 10.2337/db09-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roubenoff R. Gout and hyperuricemia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990;16:539–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doherty M, Jansen TL, Nuki G, et al. Gout: why is this curable disease so seldom cured? Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1765–1770. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Ruiz F, Carmona L, Yebenes MJ, et al. An audit of the variability of diagnosis and management of gout in the rheumatology setting: the gout evaluation and management study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:349–355. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182314d40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Japanese Society of Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolissm Japanese guideline for the management of hyperuricemia and gout: second edition. Gout Nucleic acid Res. 2010;34:109–144. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.596496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goicoechea M, De Vinuesa SG, Verdalles U, et al. Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1388–1393. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01580210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao Y, Ottenbros SA, Laverman GD, et al. Effect of a reduction in uric acid on renal outcomes during losartan treatment: a post hoc analysis of the reduction of endpoints in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus with the angiotensin ii antagonist losartan trial. Hypertension. 2011;58:2–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu P, Chen Y, Wang B, et al. Allopurinol treatment improves renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes and asymptomatic hyperuricemia: 3-year randomized parallel-controlled study. Clin Endocrinol. 2015;83:475–482. doi: 10.1111/cen.12673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chino Y, Samukawa Y, Sakai S, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor lowers serum uric acid through alteration of uric acid transport activity in renal tubule by increased glycosuria. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2014;35:391–404. doi: 10.1002/bdd.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]