Abstract

Background

Three cases of ileus have been published among dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor users in Japan. The purpose of this study was to estimate and compare incidence rates of ileus among alogliptin users and users of other DPP-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and voglibose.

Methods

We used the Medical Data Vision database in Japan to conduct a retrospective cohort study among type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients who were new users of alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or voglibose between 1 April 2010 and 30 April 2014. The primary outcome was an incident diagnosis of ileus. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to estimate ileus events over time. Adjusted Poisson regression models were used to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRR) for ileus and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) by comparing alogliptin users to users of the other study drugs.

Results

We identified 82,386 patients with T2DM. In the adjusted model, there was no difference in risk of ileus among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with patients exposed to other DPP-4 inhibitors (IRR 1.15, 95 % CI 0.75–1.75) or GLP-1 receptor agonists (IRR 0.42, 95 % CI 0.14–1.20). The risk of ileus was significantly lower among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with patients exposed to voglibose (IRR 0.55, 95 % CI 0.35–0.88).

Conclusions

The independent risk of ileus among new users of alogliptin did not significantly differ compared with new users of other DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists but was significantly lower than new users of voglibose.

Keywords: Alogliptin, Cohort study, Diabetes, DPP-4 inhibitors, Ileus

Introduction

Incretin-related drugs have been noted in recent years as a novel class of antidiabetic agents and are widely used in daily clinical practice, expanding the range of treatment options for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1]. Incretin therapies for T2DM may be broadly grouped into two major subcategories: dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like polypeptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. DPP-4 inhibitors including alogliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin, and linagliptin, are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Two additional DPP-4 inhibitors are used in Japan: teneligliptin and anagliptin. Due to the convenient oral administration, neutral body weight, and good overall tolerability [2], prescribing of DPP-4 inhibitors has been increasing. Many patients with T2DM currently receive a DPP-4 inhibitor concomitantly with other drug classes in clinical practice.

Alogliptin is a potent DPP-4 inhibitor that was approved by the MHLW in April 2010, the EMA in September 2013, and the FDA in January 2013 for use in patients with T2DM. The glycemic efficacy [reductions in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels] of alogliptin appears to be comparable with other DPP-4 inhibitors [3].

Recently, three cases of ileus—a type of nonmechanical bowel obstruction—coincident with the use of DPP-4 inhibitors were published in diabetic Japanese patients [4]. Peristalsis are wavelike contractions that help push stool through the colon and small bowel, and ileus results when peristalsis ceases. Impaired transit of intestinal contents can be caused by either mechanical obstruction or functionally deficient enteric propulsion from attenuated or uncoordinated intestinal muscle contractions. There is a paucity of epidemiological data on ileus. Available evidence suggests that ileus is a commonly seen condition in the postoperative setting where it is recognized as a common physiologic response to abdominal surgery [5]. Postoperative adhesions now account for >75 % of all small-bowel-obstructive events in the USA, but 60 % of large-bowel obstructions are caused by a neoplasm. Bowel obstruction accounts for >15 % of admissions from the emergency department for abdominal pain in the USA [6]. There are several risk factors for ileus [7], which include metabolic derangements (electrolyte disturbances, diabetic ketoacidosis or diabetic hyperosmolar coma, uremia), neurologic disorders, intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal inflammation, and severe infections such as pneumonia. Moreover, some medications (opiates, psychotropic, antihistamines, and calcium channel blockers), abdominal surgical procedures, and intra-abdominal infections/inflammation present additional risk factors for ileus [8].

Each of the three patients with incident ileus in the published report exhibited some deficiency in bowel movement. A causal association between ileus and DPP-4 inhibitor use was unclear, and all three cases had a history of risk factors for ileus. Additionally, the onset of ileus was within 40 days after initiation of DPP-4 inhibitor. However, following the publication, we felt it was pertinent to assess the association between DPP-4 inhibitor use and incident ileus. Existing evidence indicates that the actions of GLP-1 can reduce gastric emptying of liquid meals in T2DM patients. Since GLP-1 is rapidly degraded by the enzyme DPP-4, the use of a DPP-4 inhibitor can increase the GLP-1 level and might affect gastrointestinal motility [9]. However, some human studies published have not demonstrated an effect of DPP-4 inhibitors on the rate of gastric emptying [10–12]. It is postulated that ileus could result from diabetic autonomic neuropathy, hypothyroidism, and other factors that decrease intestinal motility [13].

Voglibose, an α-glucosidase inhibitor, is one of the most commonly used orally administered antidiabetic drugs in Japan and is used not only as a first treatment but also as an add-on to other antidiabetic drugs. Voglibose was launched in 1994 in Japan as an improving agent for postprandial hyperglycemia in diabetes mellitus [14]. Case reports have been published on cases of ileus in patients taking α-glucosidase inhibitors in Japan, including one case concurrent with voglibose use [13, 15, 16]. Considering that ileus has been reported during treatment with voglibose, we included this α-glucosidase inhibitor in our study.

Given the lack of available epidemiological data on the association between therapy with DPP-4 inhibitors including alogliptin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, voglibose, and risk of ileus, we conducted a pharmacoepidemiological cohort study of diabetic patients in Japan. Specific objectives of the study were to assess baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics among first-time users of alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and voglibose, and to estimate the incidence of ileus among first-time users of these treatments. The final objective was to compare the incidence rates of ileus among alogliptin users with users of other DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and voglibose to assess the relative risk (RR).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Medical Data Vision (MDV) database in Japan. The study period was 1 April 2010 through 30 September 2014 (the latest available data in the MDV) and was selected because alogliptin has been licensed in Japan since April 2010. T2DM patients who received a first-time prescription for alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or voglibose during the study period were eligible for inclusion.

The MDV is a large, commercial, electronic, record-based healthcare records database that provides inpatient and outpatient anonymous information from 153 (mainly tertiary) hospitals on 8,140,000 patients and contains detailed information on ambulatory services, hospitalizations, patient demographic characteristics (e.g., age and gender), medical diagnoses [International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems (ICD-10 codes)], as well as diagnosis name on the patient’s prescription, information on medication use (i.e., dose, quantity, and number of days of supply), information on surgery, injections, tests, diagnosis procedure combination (DPC) claims, and results of blood tests and other laboratory tests. The MDV database has been used in various epidemiologic research studies; gender and age distributions of patients in the database are approximately similar to that of national patient demographics in Japan [17].

Exposure cohorts

From the T2DM source population, we created four mutually exclusive study cohorts that included new users of alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, teneligliptin, or anagliptin), GLP-1 receptor agonists (exenatide, lixisenatide, exenatide-LAR, or liraglutide), or voglibose. Each study drug was identified using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) drug codes. Persons were eligible for the study cohorts if they met all of the following study inclusion criteria: first-time use of a study drug of interest, diagnosis of T2DM, age ≥40 years, at least 12 months of medical history in MDV prior to cohort entry, and at least 1 day of follow-up after cohort entry. Patients were excluded if they had previous prescriptions for a DPP-4 inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist or voglibose, started use of more than one of the study drugs on the same day, or had a diagnosis of ileus in the year prior to cohort entry to avoid misclassification of prevalent ileus cases as incident cases.

The cohort entry date was defined as the date that the patient received a first-ever prescription for any of the study drugs (the index prescription). The follow-up period began at cohort entry date and ended with the earliest of any of the following censoring events: incident diagnosis of ileus, end of study period (i.e., 30 September 2014), or end of index treatment episode captured as the earliest of either the ending date of the supply of the last prescription for that drug or the day before the start date of a new study drug.

Use of a study drug was defined as receipt of at least one prescription for that drug. Prescription duration was determined by the days’ supply. Cumulative duration of exposure was calculated by summing the days supply for all recorded prescriptions subsequent to the index prescription during the study period, with 30-day allowable gaps used to define a consecutive index therapy episode. A prescribing gap of >30 days or a switch to or add-on with another drug of interest marked the end of the index treatment episode.

Outcome

The primary outcome was an incident diagnosis of ileus (identified by ICD-10 codes K56.7 for Ileus, unspecified; and K56.0 for paralytic ileus) occurring after cohort entry date.

Confounders

From the MDV database, we extracted data related to potential confounders. We considered medical history such as chronic kidney disease, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, peripheral neuropathy, urinary infection, and other potential confounders believed to affect the risk of ileus including abdominal surgery, laparoscopy, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, gastrectomy, herniorrhaphy (hernia repair), intra-abdominal infections/inflammation including peritonitis, appendicitis, and diverticulitis; serious infection such as pneumonia; metabolic derangements including diabetic ketoacidosis or diabetic hyperosmolar coma; colorectal cancer, bowel disorders including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease, and celiac disease; medication history including calcium channel blockers, antihistamines, and psychotropics including phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, and opiates.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations (SD), medians with 10th–90th percentiles for continuous variables, and numbers and percentages for categorical variables were used to examine patient baseline characteristics in the cohorts of interest, and the presence of ileus. Incidence rates of ileus per 1000 person-years with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for each exposure cohort were calculated. Considering ileus is an acute condition, we assessed several different exposure time-risk-window periods: within 90 days after cohort entry, within 30 days after cohort entry, within 31–90 days after cohort entry, and ≥91 days after cohort entry.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to estimate ileus events over time in each individual exposure cohort. To take into account the relatively rare events of ileus in the study population, Poisson regression models with adjustment for potential confounding factors assessed at baseline were used to estimate incidence rate ratios for ileus and 95 % CIs by comparing the alogliptin cohort with each of the other exposure cohorts. This was carried out for the 90-day time-risk window that overlapped. This method allowed us to assess the risk quite broadly and also helped to minimize the risk of introducing a survival bias. To assess potential confounding, a bivariate analysis identified covariates associated with both exposure and outcome at the 10 % alpha level; those significantly associated with both were then tested in the models. Only those covariates significant at the 5 % alpha level were included in the final models.

Presence or absence of exposures, outcome, and medical and medication history were defined by the presence or absence of relevant prescription entries or diagnoses in the MDV database. Absence of a given medical or drug codes of interest was taken as assumed absence of the given drug therapy or diagnosis. We had complete data for patient age and only one missing entry for sex. Therefore, no missing data were imputed.

Quality control

The study was conducted in accordance with the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE) Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) (http://www.pharmacoepi.org/resources/guidelines_08027.cfm). Due to the regulation of privacy protection, it was not possible to link the primary data for case validation. The Stata syntax files provided a detailed record of the precise programming steps carried out. All data were programmed according to agreed-upon coding standards. Stata 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for data analysis.

Results

Between 1 April 2010 and 30 April 2014, there were 82,386 eligible patients with T2DM identified in the MDV database, of whom 9,663 (11.7 %), 55,919 (67.9 %), 1,904 (2.3 %), and 14,900 (18.1 %) were new users of alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitors, a GLP-1 receptor agonists, and voglibose, respectively.

Patient characteristics

Mean age at cohort entry was 68.7 years, and 60.8 % of the study population was men (Table 1). More than half of the patients with diabetes had not used any diabetes drugs in the year prior to cohort entry (57.5 %). Among patients who used antidiabetic drugs, sulfonylureas (6–22 %), insulins (10–35 %), and biguanides (3–18 %) were the most common (Table 1). Insulin therapy among alogliptin users in the year prior to cohort entry was relatively low compared with users of other DPP-4 inhibitors (12 vs. 21 %).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study and comparator cohorts

| Variable | New alogliptin users | New other DPP-4 inhibitor users | New GLP-1 receptor agonist users | New voglibose users | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 9663 (11.7) | 55,919 (67.9) | 1904 (2.3) | 14,900 (18.1) | 82,386 (100) |

| Mean age at cohort entry (SD), years | 68.97 (10.63) | 68.67 (10.86) | 62.71 (11.42) | 69.68 (10.37) | 68.75 (10.81) |

| Age group, years, N (%) | |||||

| <60 | 1752 (18.1) | 10,709 (19.2) | 714 (37.5) | 2332 (15.7) | 15,507 (18.8) |

| 60–69 | 3054 (31.6) | 17,668 (31.6) | 618 (32.5) | 4675 (31.4) | 26,015 (31.6) |

| 70–79 | 3217 (33.3) | 18,259 (32.7) | 439 (23.1) | 5263 (35.3) | 27,178 (33.0) |

| 80+ | 1640 (17.0) | 9283 (16.6) | 133 (7.0) | 2630 (17.7) | 13,686 (16.6) |

| Sex, N (%) | |||||

| Male | 5925 (61.3) | 34,059 (60.9) | 1030 (54.1) | 9071 (60.9) | 50,085 (60.8) |

| Female | 3738 (38.7) | 21,859 (39.1) | 874 (45.9) | 5829 (39.1) | 32,300 (39.2) |

| Other diabetes drugs (past year), N (%) | |||||

| None | 5378 (55.7) | 28,764 (51.4) | 1061 (55.7) | 12,151 (81.6) | 47,354 (57.5) |

| Any other diabetes drug | 4285 (44.3) | 27,155 (48.6) | 843 (44.3) | 2749 (18.5) | 35,032 (42.5) |

| Insulins | 1180 (12.2) | 11,574 (20.7) | 669 (35.1) | 1592 (10.7) | 15,015 (18.2) |

| Biguanides | 1596 (16.5) | 9426 (16.9) | 350 (18.4) | 489 (3.3) | 11,861 (14.4) |

| Sulfonylureas | 2141 (22.2) | 12,205 (21.8) | 272 (14.3) | 934 (6.3) | 15,552 (18.9) |

| Alpha glucosidase inhibitors | 758 (7.8) | 4689 (8.4) | 154 (8.1) | 275 (1.9) | 5876 (7.1) |

| Thiazolidinediones | 1181 (12.2) | 5630 (10.1) | 179 (9.4) | 385 (2.6) | 7375 (9.0) |

| Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Meglitinides | 425 (4.4) | 2692 (4.8) | 59 (3.1) | 243 (1.6) | 3419 (4.2) |

| Combinations (oral antidiabetic drugs) | 36 (0.4) | 142 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 25 (0.2) | 206 (0.3) |

| Total | 9663 (11.7) | 55,919 (67.9) | 1904 (2.3) | 14,900 (18.1) | 82,386 (100) |

| Medical history at cohort entry, N (%) | |||||

| History of ileus (prior to year preceding cohort entry) | 97 (1.0) | 722 (1.3) | 16 (0.8) | 108 (0.7) | 943 (1.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease (anytime) | 1297 (13.4) | 7486 (13.4) | 288 (15.1) | 2074 (13.9) | 11,145 (13.5) |

| Myocardial infarction (anytime) | 620 (6.4) | 3968 (7.1) | 85 (4.5) | 661 (4.4) | 5334 (6.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease (anytime) | 72 (0.8) | 459 (0.8) | 21 (1.1) | 135 (0.9) | 687 (0.8) |

| Congestive heart failure (anytime) | 2472 (25.6) | 13,799 (24.7) | 372 (19.5) | 3312 (22.2) | 19,955 (24.22) |

| Coronary artery disease (anytime) | 328 (3.4) | 1722 (3.1) | 70 (3.7) | 375 (2.5) | 2495 (3.0) |

| Diabetic retinopathy (anytime) | 1610 (16.7) | 10,954 (19.6) | 629 (33.0) | 2771 (18.6) | 15,964 (19.4) |

| Diabetic nephropathy (anytime) | 1463 (15.1) | 8800 (15.7) | 439 (23.1) | 2042 (13.7) | 12,744 (15.5) |

| Peripheral neuropathy (anytime) | 774 (8.0) | 5923 (10.6) | 320 (16.8) | 1631 (11.0) | 8648 (10.5) |

| Abdominal surgery (past year) | 33 (0.3) | 263 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | 39 (0.3) | 339 (0.4) |

| Intra-abdominal infection (past year) | 59 (0.6) | 399 (0.7) | 12 (0.6) | 77 (0.5) | 547 (0.7) |

| Serious infection (past year) | 399 (4.1) | 2658 (4.8) | 70 (3.7) | 558 (3.7) | 3685 (4.5) |

| Urinary tract infection (past year) | 285 (3.0) | 1859 (3.3) | 44 (2.3) | 331 (2.2) | 2519 (3.1) |

| Metabolic derangements (past year) | 19 (0.2) | 256 (0.5) | 37 (1.9) | 44 (0.3) | 356 (0.4) |

| Colorectal cancer (past 5 years) | 89 (0.9) | 602 (1.1) | 13 (0.7) | 122 (0.8) | 826 (1.0) |

| Medication history at cohort entry (past year), N (%) | |||||

| Calcium channel blockers | 2859 (29.6) | 16,702 (29.9) | 406 (21.3) | 2004 (13.5) | 21,971 (26.7) |

| Antihistamines | 677 (7.0) | 4073 (7.3) | 124 (6.5) | 583 (3.9) | 5457 (6.6) |

| Psychotropic medications | 103 (1.1) | 682 (1.2) | 28 (1.5) | 97 (0.7) | 910 (1.1) |

| Opiates | 396 (4.1) | 2450 (4.4) | 59 (3.1) | 288 (1.9) | 3193 (3.9) |

DPP-4 dipeptidyl peptidase-4, GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide 1

The most prevalent condition at baseline was congestive heart failure, with nearly 25 % of all patients having this condition in their medical history. Between 14 and 23 % of patients had diabetic nephropathy. Other prevalent conditions were diabetic retinopathy and chronic kidney disease, ranging between 17–33 and 13–15 %, respectively (Table 1). The most commonly prescribed medication in the year prior to cohort entry were calcium channel blockers, with approximately 27 % of patients prescribed such drugs (Table 1).

Incidence of ileus

The crude overall (all-time risk windows) incidence of ileus was 9.05 per 1000 person-years (95 % CI 7.36–11.13) for alogliptin, 10.26 per 1000 person-years (95 % CI 9.50–11.08) for other DPP-4 inhibitors, 32.16 per 1000 person-years (95 % CI 14.45–71.59) for GLP-1 receptor agonists, and 12.24 per 1000 person-years (95 % CI 10.64–14.08) for voglibose (Table 2). The incidence of ileus among users of other DPP-4 inhibitors was similar when compared with users of voglibose: 10.26 per 1000 person-years (95 % CI 9.50–11.08) and 12.24 per 1000 person-years (95 % CI 10.64–14.08), respectively.

Table 2.

Incidence of ileus among new users of alogliptin, other dipeptidyl peptide-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, and voglibose

| Exposure category new use | Events, N | Person-years at risk | Incidence rate per 1000 person-years (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alogliptin | |||

| Overall | 90 | 9941.9 | 9.05 (7.36–11.13) |

| Risk window | |||

| ≤90 days | 26 | 2052.6 | 12.67 (8.62–18.60) |

| ≤30 days | 9 | 752.8 | 11.96 (6.22–22.98) |

| 31–90 days | 17 | 1276.3 | 13.32 (8.28–21.43) |

| 91+ days | 64 | 7869.1 | 8.13 (6.37–10.39) |

| Other DPP-4 inhibitors | |||

| Overall | 642 | 62,584.9 | 10.26 (9.50–11.08) |

| Risk window | |||

| ≤90 days | 141 | 11907.8 | 11.84 (10.04–13.97) |

| ≤30 days | 56 | 4340.8 | 12.90 (9.93–16.76) |

| 31–90 days | 85 | 7431.3 | 11.44 (9.25–14.15) |

| 91+ days | 501 | 50558.5 | 9.91 (9.08–10.82) |

| GLP-1 agonists | |||

| Overall | 6 | 186.6 | 32.16 (14.45–71.59) |

| Risk window | |||

| ≤90 days | 5 | 135.0 | 37.05 (15.42–89.01) |

| ≤30 days | 2 | 74.7 | 26.76 (6.69–107.01) |

| 31–90 days | 3 | 58.7 | 51.13 (16.49–158.54) |

| 91+ days | 1 | 51.0 | 19.61 (2.76–139.24) |

| Voglibose | |||

| Overall | 196 | 16017.8 | 12.24 (10.64–14.08) |

| Risk window | |||

| ≤90 days | 63 | 3064.7 | 20.56 (16.06–26.32) |

| ≤30 days | 21 | 1138.1 | 18.45 (12.03–28.30) |

| 31–90 days | 42 | 1891.6 | 22.20 (16.41–30.05) |

| 91+ days | 133 | 12923.6 | 10.29 (8.68–12.20) |

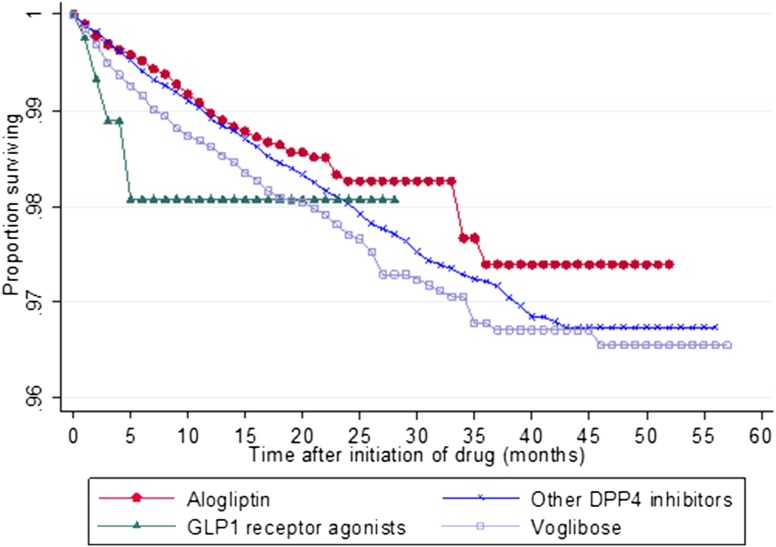

Figure 1 shows the cumulative survival pattern for the first event of ileus after cohort entry up to 5 years. At 3 months after cohort entry, 1.11 % of users of GLP-1 receptor agonists had developed ileus, compared with only 0.31, 0.29, and 0.51 % of alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitors and voglibose users, respectively. At 6 months, 1.93, 0.48, 0.59, and 0.85 % of users of GLP-1 agonists, alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitor, and voglibose had experienced ileus, respectively. At 1 year after cohort entry, the percentage of GLP-1 receptor agonist users who developed ileus remained at 1.93 %; however, 1.03, 1.09, and 1.38 % of users of alogliptin, other DPP-4 inhibitors, and voglibose, respectively, had developed ileus at that time.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for incidence of ileus after first use of alogliptin, other dipetidyl peptidae-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist, and voglibose

The incidence of ileus assessed by different time-risk-period windows is presented in Table 2. Incidence of ileus was lowest for the longest, i.e., the 91+ day time-risk window compared with the other time-risk windows (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis

In the adjusted models (model 1: alogliptin vs. other DPP-4 inhibitors—adjusted for age at cohort entry, abdominal surgery, metabolic derangement, congestive heart failure, insulin therapy; model 2: alogliptin vs. GLP-1 receptor agonists—adjusted for age at cohort entry, insulin therapy, psychotropic medication; model 3: alogliptin vs. voglibose—adjusted for age at cohort entry, history of ileus, myocardial infarction, insulin therapy, psychotropic medication) using the time-risk window of ≤90 days, there was no difference in risk of ileus among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with either of the other DPP-4 inhibitor-exposed patients [incident rate ratio (IRR) 1.15, 95 % CI 0.75–1.75] or patients exposed to GLP-1 receptor agonists (IRR 0.42, 95 % CI 0.14–1.20) (Tables 3–5). However, the risk of ileus was significantly lower among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with patients exposed to voglibose (IRR 0.55, 95 % CI 0.35–0.88).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of incidence of ileus among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with other DPP-4 inhibitors: ≤90-day exposure-risk window (N = 65,582)

| Variable | Events, N | Person-years at risk | Incidence rate ratio (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

| Exposure | ||||

| Alogliptin | 26 | 2054.2 | 1.06 (0.70–1.61) | 1.15 (0.75–1.75) |

| Other DPP-4 | 142 | 11910.4 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Age at cohort entry (years) | 168 | 13,964.6 | 1.05 (1.03–1.07)*** | 1.04 (1.03–1.06)*** |

| Abdominal surgery (past year) (yes) | 3 | 50.2 | 5.04 (1.61–15.80)** | 3.17 (1.00–10.05)* |

| Metabolic derangement (yes) | 5 | 43.6 | 9.81 (4.03–23.88)*** | 5.36 (2.15–13.33)*** |

| Congestive heart failure (yes) | 62 | 3381.4 | 1.83 (1.34–2.50)*** | 1.44 (1.05–1.98)* |

| Insulin therapy (past year) (yes) | 53 | 2332.0 | 2.30 (1.66–3.18)*** | 1.94 (1.38–2.72)*** |

GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide 1, CI confidence interval

aAdjusted for age at cohort entry, abdominal surgery, metabolic derangement, congestive heart failure, insulin therapy

*** p≤0.001 ** p≤0.01 * p≤0.05

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of incidence of ileus among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with voglibose: ≤90-day exposure-risk window (N = 24,563)

| Variable | Events | Person years at risk | Incidence rate ratio (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

| Exposure | ||||

| Alogliptin | 26 | 2054.2 | 0.62 (0.39–0.97)* | 0.55 (0.35–0.88)** |

| Voglibose | 63 | 3065.6 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Age at cohort entry (years) | 89 | 5119.8 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06)*** | 1.04 (1.01–1.06)** |

| History of ileus (prior to year preceding cohort entry) (yes) | 7 | 38.2 | 11.35 (5.25–24.55)*** | 8.58 (3.89–18.90)*** |

| Myocardial infarction (yes) | 12 | 239.2 | 3.18 (1.73–5.84)*** | 2.32 (1.24–4.35)** |

| Insulin therapy (past year) (yes) | 22 | 413.9 | 3.73 (2.31–6.04)*** | 2.87 (1.74–4.74)*** |

| Psychotropic medication (yes) | 4 | 35.2 | 6.81 (2.50–18.56)*** | 5.52 (1.98–15.40)*** |

CI confidence interval

aAdjusted for age at cohort entry, history of ileus, myocardial infarction, insulin therapy, psychotropic medication

*** p≤0.001 ** p≤0.01 * p≤0.05

Discussion

This study was conducted to further explore a potential risk of ileus related to DPP-4 inhibitor use. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to quantify and assess the risk of alogliptin use and ileus compared with other DPP-4 inhibitors and with other classes of medicines for treating T2DM, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists and voglibose. The results indicate that the unadjusted incidence of ileus among users of alogliptin was similar to rates among users of other DPP-4 inhibitors, while the rate for users of GLP-1 receptor agonists was higher. The results from our comparative analysis using the 90-day exposure-risk window indicate no difference in risk of ileus among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with patients using other DPP-4 inhibitors (IRR 1.15, 95 % CI 0.75–1.75) or those exposed to GLP-1 receptor agonists (IRR 0.42, 95 % CI 0.14–1.20). However, the magnitude of the risk estimates for the GLP-1 receptor agonists should be interpreted with caution considering that the number of patients who received GLP-1 receptor agonists and then developed ileus during the study period were small and the CI for incidence estimates were wide. Also, the character of each study cohort could be inferred by the degree of drug combination and the diabetic complications, even if precise disease duration was not available. For example, the degree of medical complication in the GLP-1 receptor agonist cohort was higher than in the other cohorts. This would imply that they had longer diabetes duration and therefore more severe autonomic dysfunction, which could have influenced the risk of ileus.

Conversely, the risk of ileus was significantly lower among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with patients exposed to voglibose (IRR 0.55, 95 % CI 0.35–0.88). The lower risk of ileus among users of alogliptin compared with users of voglibose is not surprising given the published case reports of incident ileus among patients taking α-glucosidase inhibitors [13, 15, 16], which have well-documented gastrointestinal side effects [14].

When assessing a relatively rare outcome in particular, there is a possibility that the study may be underpowered to detect true group differences with respect to the outcome. Post hoc power calculations based on our observed annual incidence of ileus among users of other DPP-4 inhibitors of 1.184 % at 11,908 patient-years exposure showed the study had 96 % power to detect a doubling of the risk of ileus (i.e., an annual incidence of 2.368 %) among users of alogliptin at our observed 2,052.6 patient-years exposure for alogliptin at 5 % significance. Therefore, this study had adequate power to detect a notable elevated risk of development of ileus with use of alogliptin.

There are several risk factors for ileus. Despite the fact that abdominal surgical procedures are one of the identified risk factors for the development of ileus, this risk factor indicated a significant association in only one multivariate analysis of incidence of ileus among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with other DPP-4 inhibitors (Table 3) but not the other analyses. However, it is important to point out that the number of patients who had had abdominal surgery was relatively small (0.4 % of the cohort). Multivariate analyses consistently showed that age and recent insulin therapy were risk factors for ileus (Tables 3–5). Increasing age is an established risk factor for ileus [8]; however, we found no other evidence that insulin therapy is a risk factor for ileus. Use of psychotropic medication was also a risk factor in two of our multivariate models (Tables 4 and 5), a finding that is supported by previous studies [7, 18 ].

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of incidence of ileus among patients exposed to alogliptin compared with GLP-1 receptor agonists: ≤90-day exposure-risk window (N = 11,567)

| Variable | Events | Person years at risk | Incidence rate ratio (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

| Exposure | ||||

| Alogliptin | 26 | 2054.2 | 0.34 (0.13–0.89)* | 0.42 (0.14–1.20) |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | 5 | 135.0 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Age at cohort entry (years) | 31 | 2189.1 | 1.05 (1.01–1.09)** | 1.05 (1.02–1.09)** |

| Insulin therapy (past year) (yes) | 10 | 249.0 | 3.71 (1.75–7.88)*** | 2.62 (1.15–5.98)* |

| Psychotropic medication (yes) | 2 | 23.79 | 6.28 (1.50–26.30)** | 5.59 (1.30–23.97)*** |

GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide 1

aAdjusted for age at cohort entry, insulin therapy, psychotropic medication

*** p≤0.001 ** p≤0.01 * p≤0.05

A significant strength of this real-world evidence study was use of the large Japanese MDV database, which provided data on a cohort of over 82,300 patients with T2DM who were users of the diabetes medications of interest. Several study limitations should be noted: As with any observational study research, the possibility of residual confounding or confounding by indication cannot be excluded. The results of the study can only be generalized to new initiators of DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and voglibose therapy in Japanese healthcare settings and not to other healthcare settings and populations. There may be a risk of information bias if patients sought care or were dispensed the drug in healthcare institutions that did not contract with the MDV. As the disease might have started before patients’ entry into the database, we were not able to access disease duration for the patients with prevalent T2DM. However, this observational study provided evidence that the crude overall incidence of ileus among users of alogliptin and other DPP-4 inhibitors was similar, while the rate for users of GLP-1 receptor agonists was higher. In addition, the independent risk of ileus among new users of alogliptin did not significantly differ compared with new users of other DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists but was significantly lower than new users of voglibose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Neila N. Smith for her advice during the study and thoughtful review and comments on our manuscript. The authors also thank Elizabeth Suarez for editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest except that they are all employees of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Ethics policy

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Srinivasan BT, Jarvis J, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Recent advances in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:524–531. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.067918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richard KR, Shelburne JS, Kirk JK. Tolerability of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors: a review. Clin Ther. 2011;33:1609–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFronzo RA, Fleck PR, Wilson CA, Mekki Q, Alogliptin Study Group Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor alogliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2315–2317. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanasaki K, Konishi K, Hayashi R, Shiroeda H, Nomura T, Nakagawa A, Nagai T, Takeda-Watanabe A, Ito H, Tsuda S, Kitada M, Fujii M, Kanasaki M, Nishizawa M, Nakano Y, Tomita Y, Ueda N, Kosaka T, Koya D. Three ileus cases associated with the use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in diabetic patients. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:673–675. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holte K, Kehlet H. Postoperative ileus: a preventable event. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1480–1493. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayanga AJ, Bass-Wilkins K, Bulkley GB. Current management of small-bowel obstruction. Adv Surg. 2005;39:1–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden GE, Sprouse KL. Bowel obstruction and hernia. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29:319–345. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen J, Meyer JM. Risk factors for ileus in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:592–598. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marathe CS, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Effects of GLP-1 and incretin-based therapies on gastrointestinal motor function. Exp Diabetes Res. 2011;2011:279530. doi: 10.1155/2011/279530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeFronzo RA, Okerson T, Viswanathan P, Guan X, Holcombe JH, MacConell L. Effects of exenatide versus sitagliptin on postprandial glucose, insulin and glucagon secretion, gastric emptying, and caloric intake: a randomized, cross-over study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2943–2952. doi: 10.1185/03007990802418851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vella A, Bock G, Giesler PD, Burton DB, Serra DB, Saylan ML, Deacon CF, Foley JE, Rizza RA, Camilleri M. The effect of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition on gastric volume, satiation and enteroendocrine secretion in type 2 diabetes: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Clin Endocrinol Oxf. 2008;69:737–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vella A, Bock G, Giesler PD, Burton DB, Serra DB, Saylan ML, Dunning BE, Foley JE, Rizza RA, Camilleri M. Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition on gastrointestinal function, meal appearance, and glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:1475–1480. doi: 10.2337/db07-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azami Y. Paralytic ileus accompanied by pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis after acarbose treatment in an elderly diabetic patient with a history of heavy intake of maltitol. Intern Med. 2000;39:826–829. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.39.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwamoto Y, Kashiwagi A, Yamada N, Terao S, Mimori N, Suzuki M, Tachibana H. Efficacy and safety of vildagliptin and voglibose in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:700–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishii Y, Aizawa T, Hashizume K. Ileus: a rare side effect of acarbose. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1033. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.9.1033a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oba K, Suzuki K, Ouchi M, Matsumura N, Suzuki T, Nakano H. Repeated episodes of paralytic ileus in an elderly diabetic patient treated with voglibose. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:182–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00575_13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urushihara H, Taketsuna M, Liu Y, Oda E, Nakamura M, et al. Increased risk of acute pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes: an observational study using a Japanese hospital database. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e53224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Hert M, Hudyana H, Dockx L, Bernagie C, Sweers K, Tack J, Leucht S, Peuskens J. Second-generation antipsychotics and constipation: a review of the literature. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]