Abstract

Background:

In high-fat diet-fed mice, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta) has been shown to play a key role in hepatic steatosis. However, it remains unknown whether IL-1 beta could be associated with different grades of steatosis in obese humans.

Materials and Methods:

Morbidly obese patients (n = 124) aged 18–65 years were divided into four groups: no steatosis (controls), mild steatosis, moderate steatosis, and severe steatosis using abdominal ultrasound. IL-1 beta serum levels and liver function tests were measured and significant differences were estimated by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test.

Results:

IL-1 beta serum levels significantly increased in morbidly obese patients with mild (11.38 ± 2.40 pg/ml), moderate (16.72 ± 2.47 pg/ml), and severe steatosis (23.29 ± 5.2 pg/ml) as compared to controls (7.78 ± 2.26 pg/ml). Liver function tests did not significantly change among different grades of steatosis.

Conclusion:

IL-1 beta serum levels associate better with steatosis degree than liver function tests in morbidly obese population.

Keywords: Fatty liver, interleukin-1 beta, liver functions tests, morbid, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Simple steatosis is characterized by progressive fat accumulation in the liver and is considered to be the initial step in the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis, and liver failure.[1,2] Liver function tests are typical biochemical markers to identify patients with NASH and cirrhosis, without showing utility in steatosis until now.[3]

Cytokines have been shown to play a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of steatosis in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice especially interleukin (IL)-1 beta (IL-1 beta).[4] However, as far as we know, there are no studies evaluating whether IL-1 beta could be modified depending on the simple steatosis degree in obese patients.[5]

Our main goal was to determine the serum levels of IL-1 beta in morbidly obese patients with different degrees of simple steatosis, while also comparing the association level of IL-1 beta and liver function tests with severity of steatosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Morbidly obese women and men (n = 124) aged 18–65 years, attending to the Department of Internal Medicine and the Clinic for Obesity of the General Hospital of Mexico from October 2014 to December 2017, were included in the study by convenience sampling and divided into four groups: controls (no steatosis), mild steatosis, moderate steatosis, and severe steatosis. Steatosis degree was scored by two independent senior hepatologists using abdominal ultrasound imaging, as previously described.[6] All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in strict adherence to the Helsinki Declaration. Exclusion criteria included previous diagnosis of acute or chronic hepatic disease, inflammatory or autoimmune disorders, acute or chronic infectious diseases, and neoplastic disorders, as well as pregnancy, lactation, and any kind of anti-inflammatory medical treatment. Blood samples were collected from each participant after 10–12 h fasting to avoid procedural variations.

Liver function tests and interleukin-1 beta serum levels

Liver function tests, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and total bilirubin, were measured from serum samples by enzymatic assay (Megazyme International, Ireland). Blood glucose, insulin, HbA1c, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides were also measured according to the manufacturer's instructions (Megazyme International, Ireland). IL-1 beta serum levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Peprotech, Mexico).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey test. ANOVA results were corrected using the Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. Women/men proportion in each group was evaluated using the Chi-square test. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 6.01 software, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA 92037 USA. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

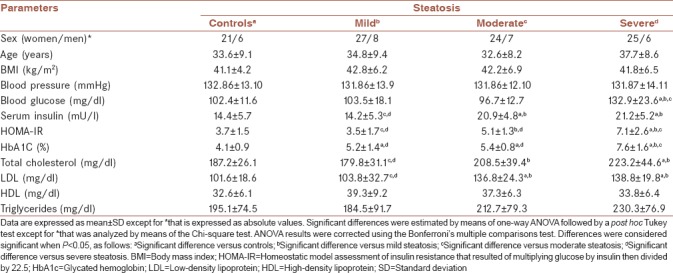

No significant differences were found in women/men proportion, age, body mass index, blood pressure, HDL, and triglycerides between control subjects (n = 27) and patients with mild (n = 35), moderate (n = 31), or severe steatosis (n = 31) [Table 1]. Severe steatosis was accompanied by significantly increased levels of blood glucose, insulin resistance, insulin, glycated hemoglobin, cholesterol, and LDL. Moderate steatosis was characterized by hyperinsulinemia resulting in low glucose values, even though insulin resistance was also increased in these patients. Mild steatosis was hallmarked by having similar levels of blood glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, cholesterol, and LDL than those found in morbidly obese patients without steatosis [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic and biochemical characteristics of the study subjects

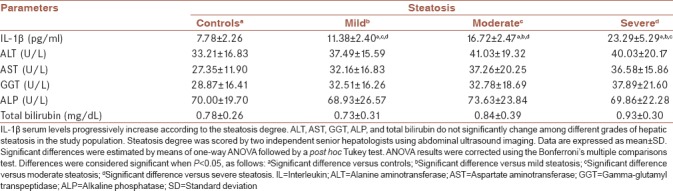

All patient groups significantly differed from each other regarding IL-1 beta serum levels. As a matter of fact, IL-1 beta progressively elevated as the severity of steatosis also increased [Table 2]. Morbidly obese participants without steatosis (controls) showed 7.78 ± 2.26 pg/ml IL-1 beta in blood as compared to patients with mild, moderate, and severe steatosis, who exhibited 11.38 ± 2.40, 16.72 ± 2.47, and 23.29 ± 5.2 pg/ml IL-1 beta, respectively [Table 2]. Lower-upper 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for controls were 6.88–8.67 pg/ml IL-1 beta. On the contrary, lower-upper 95% CI for mild, moderate, and severe steatosis rose to 10.55–12.21, 15.81–17.63, and 21.34–25.23 pg/ml IL-1 beta, respectively. No significant differences were found in ALT, AST, GGT, ALP, and total bilirubin between control participants and patients with mild, moderate, or severe steatosis [Table 2].

Table 2.

Serum levels of interleukin-1 β and liver function tests in morbidly obese patients with hepatic steatosis

DISCUSSION

IL-1 beta is a member of the IL-1 cytokine family with prominent functions in the regulation of the inflammatory response as well cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.[7,8] However, IL-1 beta has now emerged as a major contributor in steatosis development by inducing hepatic lipogenesis and triglyceride overproduction in HFD-fed mice.[3,9] Consistent with previous information, our results demonstrate for the first time that IL-1 beta serum levels clearly increase in morbidly obese patients that show the most severe stages of steatosis, which in turn concurs with prior studies also reporting IL-1 beta elevation in portal and systemic blood of HFD-fed mice with hepatic steatosis.[10]

A growing body of studies have consistently reported increasing serum levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 in NASH patients.[11,12] However, as far as we know, IL-1 beta had never been reported in morbidly obese patients with simple steatosis.[6,11,13] Interestingly, in morbidly obese participants without steatosis, serum IL-1 beta ranged from 2.02 to 11.63 pg/ml. On the contrary, in morbidly obese patients with mild, moderate, or severe steatosis, IL-1 beta levels were found between 4.87 and 19.07, 11.82 and 23.53, and 10.62 and 34.47 pg/ml, respectively, which suggest that serum values of this cytokine considerably increase only in severe grades of hepatic fat accumulation.

Finally, numerous studies have persistently shown that patients with simple steatosis exhibit normal liver function tests, except those who are progressing to NASH.[14,15] Our data expand on this body of work by revealing that liver function tests do not change in morbidly obese patients with different degrees of steatosis. In this sense, IL-1 beta appears to associate better with hepatic steatosis than liver function tests in patients with morbid obesity and should be further investigated in clinical prospective studies.

CONCLUSION

The serum levels of IL-1 beta associate better with severity of simple steatosis than liver function tests in morbidly obese population.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Grant no. 290345-2017-2 from the Fondo Sectorial de Investigación y Desarrollo en Salud y Seguridad Social SS/IMSS/ISSSTE/CONACYT-México to G.E.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research project number 290345-2017-2. Ethical approval number DIC/11/UME/05/029.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haghighatdoost F, Salehi-Abargouei A, Surkan PJ, Azadbakht L. The effects of low carbohydrate diets on liver function tests in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:53. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.187269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pezeshki A, Safi S, Feizi A, Askari G, Karami F. The effect of green tea extract supplementation on liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:28. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.173051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obika M, Noguchi H. Diagnosis and evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Exp Diabetes Res 2012. 2012:145754. doi: 10.1155/2012/145754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negrin KA, Roth Flach RJ, DiStefano MT, Matevossian A, Friedline RH, Jung D, et al. IL-1 signaling in obesity-induced hepatic lipogenesis and steatosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paquissi FC. Immune imbalances in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: From general biomarkers and neutrophils to interleukin-17 axis activation and new therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2016;7:490. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paredes-Turrubiarte G, González-Chávez A, Pérez-Tamayo R, Salazar-Vázquez BY, Hernández VS, Garibay-Nieto N, et al. Severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with high systemic levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and low serum interleukin 10 in morbidly obese patients. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s10238-015-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn M, Frey S, Hueber AJ. The novel interleukin-1 cytokine family members in inflammatory diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:208–13. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vela JM, Molina-Holgado E, Arévalo-Martín A, Almazán G, Guaza C. Interleukin-1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:489–502. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stienstra R, Saudale F, Duval C, Keshtkar S, Groener JE, van Rooijen N, et al. Kupffer cells promote hepatic steatosis via interleukin-1beta-dependent suppression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activity. Hepatology. 2010;51:511–22. doi: 10.1002/hep.23337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nov O, Shapiro H, Ovadia H, Tarnovscki T, Dvir I, Shemesh E, et al. Interleukin-1β regulates fat-liver crosstalk in obesity by auto-paracrine modulation of adipose tissue inflammation and expandability. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuman MG, Cohen LB, Nanau RM. Biomarkers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:607–18. doi: 10.1155/2014/757929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tilg H, Moschen AR, Szabo G. Interleukin-1 and inflammasomes in alcoholic liver disease/acute alcoholic hepatitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2016;64:955–65. doi: 10.1002/hep.28456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamari Y, Shaish A, Vax E, Shemesh S, Kandel-Kfir M, Arbel Y, et al. Lack of interleukin-1α or interleukin-1β inhibits transformation of steatosis to steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1086–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamali R, Arj A, Razavizade M, Aarabi MH. Prediction of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via a novel panel of serum adipokines. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2630. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machado MV, Cortez-Pinto H. Non-invasive diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. A critical appraisal. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1007–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]