Abstract

Background:

Lead effects on children and pregnant women are grave, and screening tests would be logical to detect high blood lead levels (BLLs) in early stages.

Materials and Methods:

Blood samples were taken from the pregnant mothers who referred to midwifery clinic with further phone interview postdelivery.

Results:

In 100 patients evaluated, the mean age was 29 ± 5 years (median interquartile range gestational age of 33 [24, 37] weeks). There was a significant correlation between polluted residential area and median BLL (P = 0.044) and substance exposure (P = 0.02). The median BLL was significantly lower in those without a history of lead toxicity in the family (P = 0.003). The only factor that could predict the BLL levels lower than 3.2 and 5 μg/dL was living in the nonindustrial area. All pregnant women delivered full-term live babies.

Conclusion:

Positive history of lead toxicity in the family and living in polluted areas may pose a higher BLL in pregnant women.

Keywords: Lead, poisoning, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Elemental lead toxicity is a new major problem in Iran. The symptoms are often wide and nonspecific, from mood and sleep disturbance, paresthesia, and myalgia to abdominal pain, anemia, constipation, loss of appetite, and irritability. Lead toxicity can reveal as an urgent surgical condition or a chronic illness.[1,2]

In the recent years, a new type of lead poisoning has increased in Iranian society: lead poisoning due to lead-contaminated opium.[3,4,5,6] Risk factors for lead toxicity include recent immigration from underdeveloped countries, history of lead toxicity in relatives or the patient him/herself, pica, occupational exposure, alternative remedies or cosmetics, use of lead-glazed pottery, lead paint, lead-contaminated soil and water, and nutritional status.[7]

Lead poisoning may cause serious complications including abdominal colic, anemia, lead encephalopathy, and growth retardation, especially in children.[8] In pregnant women, lead causes decreased fertility, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.[9] The current risk of lead exposure in Iranian pregnant women, however, is not well characterized.

Even low levels of lead exposure are considered hazardous to pregnant women. Follow-up blood lead testing is recommended for pregnant women with blood lead level (BLL) ≥5 μg/dL and their babies.[8]

In our region, limited studies have evaluated the frequency of lead poisoning in pregnant women. In a study on 124 pregnant women from Riyadh, mean maternal and cord lead were measured to be 5.49 ± 2.6 and 4.14 ± 1.8 μg/dL, respectively.[10] Recently, the Center for Disease Control has decreased the allowable threshold of lead level from 25 to 10 μg/dL although this has even been less in pregnant women.[11] Mirghani mentioned that in 20 pregnant women out of 134 cases, a BLL over 20 μg/dL was detected.[12] The author concluded that lead affected on the three pregnancy outcomes: gestational age, premature rupture of the membrane, and birth weight. Such studies have not been performed in Iran.

We aimed to screen BLL in pregnant women who referred to Loghman Hakim Hospital midwifery clinic as a referral center in Tehran. We tried to show the importance of such studies to persuade other future studies to be performed in this regard. This study is the first one performed on pregnant women after outbreak of lead poisoning due to lead-contaminated opium.[5]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In a descriptive cross-sectional study, pregnant women who referred to our midwifery clinic for follow-up evaluations were entered by a nonprobable consecutive sampling. Assuming a = 0.05, an error of 0.02, and a standard deviation (SD) of 0.1, 100 pregnant women were recruited. All pregnant women who referred to our midwifery clinic were included from the study. Sampling was continued until the sample size was reached.

Only those who did not wish to be included were excluded from the study. The blood samples were taken and tested using LeadCare II. A questionnaire containing epidemiological and laboratory data, history of exposure to substances and lead in the family and women, and using calcium and iron supplements was filled for each individual. Participants were followed by phone to see pregnancy outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Distribution of variables was tested for skewness using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normal data are presented as mean (±SD) and nonparametric data are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Student's t-test was used to compare mean values of normally distributed data. Differences in qualitative data (expressed as percentages) groups were assessed using the Chi-squared and Fisher's exact test. “Enter” logistic regression analysis was used to determine independent factors contributing to the risk of high/low lead blood level by entering. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

The study was approved by our Local Ethics Committee (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1396.74).

RESULTS

Mean age was 29 ± 5 years (19–42 years). They were mostly housewives (90 cases; 90%) and well-educated, and all had referred to participate in the educational programs before childbearing. The median (IQR) gestational age was 33 (24, 37) weeks with gravid 2 (1, 3), para 1 (0, 1), and abortion 0 (0, 0). One (1%) was addicted to opium and two (2%) had opium-addicted husbands. Almost 26 cases (26%) lived in new houses, 58% of pipe types used in their houses were new, and 55% were nonmetal. Eleven patients lived in probable lead-contaminated industrial areas with factories located around them.

Median BLL was 3.4 (1.6, 5.1) (1.6–27 μg/dL). There was a significant association between polluted residential area and median BLL (P = 0.044) and substance exposure (P = 0.02). Median BLL was significantly lower in those without a family history of lead toxicity (P = 0.003). Furthermore, those who used iron–calcium supplements had higher BLLs (P = 0.03).

The most common sign was anemia (43%). One case had a BLL of 27 μg/dL and in five cases BLL was >5 μg/dL.

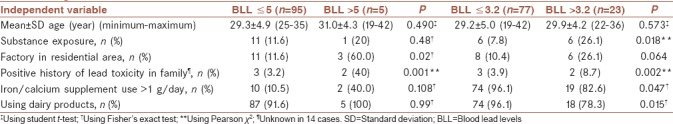

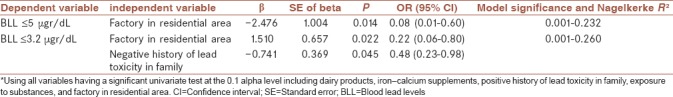

Table 1 shows comparison of BLL in selected variables. After “Enter” regression analysis, it was shown that the only factor that could predict the BLL levels lower than 3.2 and 5 μg/dL was living in the nonindustrial area [Table 2]. Phone interview was done after estimated date of giving birth. Response rate was 90% with no report of spontaneous abortions, preterm births, low birth weight, or macrosomia.

Table 1.

Comparison of different variables between pregnant women with blood lead levels below and above 3.2 and 5 μgr/dL

Table 2.

“Enter” regression analysis of the variables with significant association to blood lead level*

DISCUSSION

In the Middle East, there are few studies focusing on pregnant women and children who easily absorb lead in the highest quantities.[8,9,10] Although our patients’ BLLs were fairly low, it has been shown that these low levels can also cause complications. Vigeh et al. showed that adverse pregnancy outcomes were observed at “acceptable” BLLs ≤10 μg/dL.[13] This emphasizes on the importance of BLL screening tests in pregnancy, especially in countries with endemic lead toxicity such as ours.

Golmohammadi et al. evaluated maternal BLL, newborn, cord blood, and colostrums in polluted areas of Tehran and compared with nonpolluted areas. The mothers’ and newborns’ cord blood, and colostrums lead levels were significantly higher in polluted areas.[14] Kelishadi et al. found high concentration of lead in human milk of lactating women, who were living in Isfahan, an industrialized city.[15]

Pourjafari et al. evaluated the fetal death rates in lead mine and dye-houses workers’ pregnant women in Hamadan. The rates of abortions and stillbirths were 13.15 and 13.30%, respectively.[16]

Mothers who consumed supplements had higher BLLs which may reflect the higher incidence of anemia in them mandating consumption of more supplements.

Exposure to opium and history of opium use in the family were other factors related to high BLLs, although this relation was not confirmed in regression analysis. This can be completely understood since the opium lead can also be inhalationally absorbed.[17]

The other finding is the significant relation between consuming spices/herbal products and BLL. Gowsami and Mazumdar reported lead contamination in black pepper, cinnamon, cardamom, cloves, coriander, cumin, thyme, turmeric, garlic, and ginger.[18] This, however, is not proven in our region and should be considered in future studies in our country.

Limitations

It should be emphasized that we only evaluated 100 patients from a midwifery clinic in only one referral center in Tehran and reached such results. Definitely, future studies on larger sample sizes and even in country-wide scales are warranted to fully evaluate this situation in Iranian pregnant women.

Using small sample size in a single referral center in Tehran and obtaining high lead levels shows the importance and great need for screening programs in the Iranian pregnant women.

CONCLUSION

Higher BLLs may be seen in pregnant women who reside in industrial area and are exposed to substances. Positive history of lead toxicity in the family may pose a higher BLL. Complete control of the environmental exposure to lead is warranted in pregnant women.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Clinical Research and Development Center of Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K, Saraie M, Ghasemi M, Izadi N, Chavoshi F, Khajehmehrizi A. Assessment of peripheral neuropathy in male hospitalized patients with lead toxicity in Iran. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:6–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alinejad S, Aaseth J, Abdollahi M, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Mehrpour O. Clinical aspects of opium adulterated with lead in Iran: A review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;122:56–64. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamani N, Jamshidi F. Abuse of lead-contaminated opium in addicts. Singapore Med J. 2012;53:698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zamani N, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Latifi M. Abdominopelvic CT in a patient with seizure, anemia, and hypocalcemia. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:27–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghane T, Zamani N, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Beyrami A, Noroozi A. Lead poisoning outbreak among opium users in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2016-2017. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:165–72. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.196287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamani N, Hassanian-Moghaddam H. Notes from the field: Lead contamination of opium-Iran, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;66:1408–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm665152a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the Identification and Management of Lead Exposure in Pregnant and Lactating Women. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klitzman S, Sharma A, Nicaj L, Vitkevich R, Leighton J. Lead poisoning among pregnant women in New York city: Risk factors and screening practices. J Urban Health. 2002;79:225–37. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Environmental Health Division. Blood Lead Screening Guidelines For Pregnant & Breastfeeding Women in Minnesota. Minnesota Department of Health. 2015. [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 05]. Available from: http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/eh/lead/reports/pregnancy/pregnancyguidelines.pdf .

- 10.al-Saleh I, Khalil MA, Taylor A. Lead, erythrocyte protoporphyrin, and hematological parameters in normal maternal and umbilical cord blood from subjects of the Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. Arch Environ Health. 1995;50:66–73. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1995.9955014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Saleh I. Sources of lead in Saudi Arabia: A review. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1998;17:17–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirghani Z. Effect of low lead exposure on gestational age, birth weight and premature rupture of the membrane. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:1027–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vigeh M, Yokoyama K, Seyedaghamiri Z, Shinohara A, Matsukawa T, Chiba M, et al. Blood lead at currently acceptable levels may cause preterm labour. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:231–4. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.050419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golmohammadi T, Ansari M, Nikzamir A, Safary R, Elahi S. The effect of maternal and fetal lead concentration on birth weight: Polluted versus non-polluted areas of Iran. Tehran Univ Med J. 2007;65:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelishadi R, Hasanghaliaei N, Poursafa P, Keikha M, Ghannadi A, Yazdi M, et al. A randomized controlled trial on the effects of jujube fruit on the concentrations of some toxic trace elements in human milk. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:108. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.193499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pourjafari H, Rabiee S, Pourjafari B. Fetal deaths and sex ratio among progenies of workers at lead mine and dye-houses. Genet Third Millennium. 2007;5:1057–60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lead Toxicity. [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 05]. Available from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=34&po=6 .

- 18.Gowsami K, Mazumdar I. Lead poisoning and some commonly used spices: An Indian scenario. IJAIR. 2014;3:433–5. [Google Scholar]