ABSTRACT

The Global Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis has achieved extraordinary success in reducing transmission and preventing morbidity through mass drug administration (MDA) to the population at-risk. Brazil is the only currently using diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) alone for MDA, so an assessment of its effectiveness is needed. We report the trends of filarial markers in a cohort of 175 individuals infected with Wuchereria bancrofti in areas that underwent MDA in the city of Olinda, Northeastern Brazil. The prospective study was conducted between 2007 and 2012 (corresponding to five annual MDA rounds). The quantification of microfilaraemia (QMFF) was assessed by filtration. Circulating filarial antigen (CFA) was detected through immunochromatographic point-of-care test (POCT-ICT) and Og4C3-ELISA whereas antifilarial antibody titres (IgG4) were assessed through Bm14 assay. The CFA and IgG4 titres were measured by Optical Density (OD). The main characteristics at baseline, MDA coverage and the trend of filarial infection markers during follow up were described. The trend of filarial markers in relation to time (years of MDA), sex and age were analysed through Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models. The models demonstrated a significant decrease in all markers during MDA. The probability of remaining positive by QMFF and POCT-ICT diminished 70% and 46%, respectively, after each MDA round. There was a significant annual drop in CFA (−0.290 OD) and IgG4 antibodies titres (−0.303 OD). This study provides evidence that MDA with DEC alone can be effective in the elimination of LF in Brazil.

KEYWORDS: Lymphatic filariasis, Wuchereria bancrofti, mass drug administration, diethylcarbamazine citrate, prevention and control

Introduction

Lymphatic Filariasis (LF) is considered one of the seven potentially eradicable infectious diseases worldwide [1]. In the Americas, Brazil, Dominican Republic, Guyana, and Haiti are currently considered to have active transmission of LF caused by Wuchereria bancrofti [2].

In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF) with the goal to eliminate the disease by the year 2020 [2]. The main strategies of the GPELF are interrupting transmission via mass drug administration (MDA) for the entire population at-risk, as well as morbidity management for those already clinically affected [3].

Between 2000–2015, more than six billion doses of MDA were delivered to more than 500 million people in 39 countries, turning the GPELF into one of the most rapidly expanding global health programs in the history of public health. It is estimated that this intervention has prevented or cured more than 97 million LF cases and has led to a significant reduction of the global population at risk [3,4].

Diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) is the primary drug of choice for MDA in LF endemic areas where W. bancrofti is the only circulating filarial parasite. To interrupt LF transmission,WHO recommends annual MDA via DEC plus albendazole (ALB) or – in areas of Onchocerciasis or Loa loa – ALB plus ivermectin (IVM) for the entire at-risk population over at least 5 years and a minimum MDA coverage rate of 65% [1,3,5]. In 2011, approximately 150 million children in all endemic countries were treated (DEC +ALB, or IVM +ALB) through GPELF programmes6. In Brazil, unlike most countries, the Ministry of Health and local health authorities decided to use DEC monotherapy in single annual doses (6 mg/kg) for MDA [6,7]. This decision was based on a Cochrane review and a Brazilian clinical trial, neither of which conclusively demonstrated that DEC-ALB co-administration is more effective than DEC alone [8,9]

Several studies have reported the effectiveness the WHO-recommended scheme of DEC plus ALB in interrupting filarial transmission in the target population [10–13]. Studies that monitored microfilariae (mf) kinetics in populations treated with annual single doses of DEC and ALB demonstrate a striking reduction in mf prevalence after initiating MDA, primarily after the third dose [14,15]. They also indicate a sharp decrease in circulating filarial antigen (CFA) [16] and antifilarial antibody rates after three round of MDA, although this reduction was less pronounced than for that observed for mf [10,11].

Brazil is the only currently using diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) alone for MDA [9,17], so an assessment of its effectiveness is needed. In this paper, we report the temporal trend of filarial markers (mf, CFA and antifilarial antibodies) among infected individuals who underwent MDA in Northeastern Brazil.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

We followed a cohort of 175 residents infected with W. bancrofti from two sentinel areas (Alto da Bondade and Alto da Conquista neighborhoods) in the city of Olinda between 2007 and 2012, corresponding to a period of five annual doses of MDA

Olinda is located in the Metropolitan Region of Pernambuco state, has a territorial area of 41,659 km2, a population of nearly 400,000 (population density 9,000 inhabitants/km [2,18] and is currently considered one of the remaining foci of LF in Brazil1 [19,20]. A population based filarial survey conducted in 2001 found mf and CFA prevalences of 1.3%19 and 31.7%20, respectively.

MDA with DEC alone began in 2007 in both sentinel areas. As in other endemic areas of Olinda, all residents aged between 4 and 65 years old (except those with decompensated heart disease and hepatic or renal dysfunction) underwent MDA during home visits and under the direct observation of community health workers (CHW). The MDA regimen was an annual single dose of DEC (6 mg/kg) according to age and gender, as described elsewhere [21,22]. MDA coverage in the study area ranged from 88.2% to 86.3% over five rounds of MDA (Health Department of Olinda, data not published).

Study participants (mf and/or CFA-positive) in the sentinel areas were identified in a door-to-door survey using immunocromatographic point-of-care test (POCT-ICT) (BinaxNOW, Binax, Inc., Maine, USA) and thick blood film (TBF) performed six months before starting MDA. A total of 80 resident were positive for mf via TBF and 110 positive for CFA via POCT-ICT, and thus, were designated as the population to be followed during MDA.

Follow-up visits after the start of MDA were performed approximately two months before the next annual round of MDA. During visits, participants were asked about their adherence to MDA and provided a nocturnal (between 11:00 pm and 1:00 am) finger prick (100 µL) and venous blood (10 mL) collection for parasitological and immunological tests.

Laboratory assays

Blood samples collected in the field were transported under refrigeration to the laboratory of the National Lymphatic Filariasis Reference Center at Instituto Aggeu Magalhães/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz-Pernambuco (NLFRC/IAM/FIOCRUZ-PE). Total blood and serum were stored at temperatures of 4–20°C, respectively, until each test could be conducted under standard operating procedures [21].

The quantification of mf by filtration (QMFF) (Nucleopore®) was performed using five mL venous blood samples. CFA was screened through POCT-ICT (finger prick blood samples) and Og4C3-ELISA (TropBio®, Pty Ltd, Townsville, Queensland, Australia), whereas specific filarial antibodies (IgG4) were detected using the Bm14 assay (Filariasis CELISA, Cellabs Pty. LTd., Brookevale, Australia). The CFA and IgG4 titres were measured via Optical Density (OD). All immunological tests (POCT-ICT, Bm14 and Og4C3-ELISA) were carried out and interpreted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as described elsewhere [23,24].

Data analysis

Data analysis included all subjects who took at least one dose of MDA and parasitological and immunological testing at baseline. Participant characteristics at baseline, drug coverage rates, and trends of different laboratory markers of filarial infection during MDA were described.

Trends of all laboratory test results in relation to the number of MDA rounds, sex and age (in years) during follow-up were analysed through Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models. This analytical approach fits models for categorical (or continuous) repeated measures that are correlated and clustered, allowing assessment of the effect of an intervention/exposure to the event over time (time trend) [25].

The parameters of each test were estimated in separate models, assuming an independent correlation structure between repeated measures for each study participant. The parameters of tests with categorical results (positive or negative mf or CFA by POCT-ICT) were estimated through logistic regression. Among tests providing continuous results, mf density as measured via QMFF was estimated through negative binomial regression and Og4C3 and Bm14 titres were estimated through linear regression models. A 5% significance level was used. Data entry and analysis were performed using Epiinfo 3.5.1 and SPSS 17.0 programs, respectively

Ethical considerations

This research was conducted under the responsibility of the NCLF, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the IAM/FIOCRUZ-PE (CEP/IAM/FIOCRUZ: 74/06 and CAEE: 0069.0.095.000–06).

Results

Among the 190 infected individuals initially detected (POCT-ICT and/or TBF positive) in the pre-MDA survey, 175 (92.1%) agreed to be followed during the community-wide annual MDA. Table 1 describes the study participants´ main characteristics at baseline. The majority were male, had a mean age of 23.8 (range: 5–70) years, and over 60% were treated with five doses of MDA. Of the participants, 164 were positive via POCT-ICT, of which 11 had undetermined results. Seventy nine were mf positive via QMFF and their mf density ranged from 1 to 1,834 mf/mL. MDA coverage rates by round of MDA ranged from 78.9% in the first round (2007) to 91.0% in the second round (2008) among study participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the study population. Olinda, Brazil, 2007–2012.

| Variable | Total subjects | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean ±SD | 175 | 24 ± 17 | |

| Male gender,% | 103 | 58.9 | |

| Microfilaria loada (mf/mL), Median (range) | 78 | 88 (1 −1,834) | |

| Microfilaria positivesa, % | 79 | 45,1 | |

| CFAb, positive (%) | 164 | 164 (100.0) | |

| Number of MDA doses taken (N, %) | |||

| 5 | 99 | 56.6 | |

| 1–4 | 66 | 37.7 | |

| None | 10 | 5.7 | |

| Number of examined and percentage of MDA treated during follow-up | |||

| Follow up visits | Examined | Treated, n (%) | Loss follow-up, n (%) |

| Pre-treatment | 175 | - | - |

| 1º | 175 | 137 (78.3) | - |

| 2º | 133 | 121 (91.0) | 42 (24.0) |

| 3º | 128 | 113 (88.3) | 47 (26.9) |

| 4º | 125 | 110 (88.0) | 50 (28.6) |

| 5º | 119 | 106 (89.1) | 56 (32.0) |

aFiltration technique bICT test; 11 undetermined result

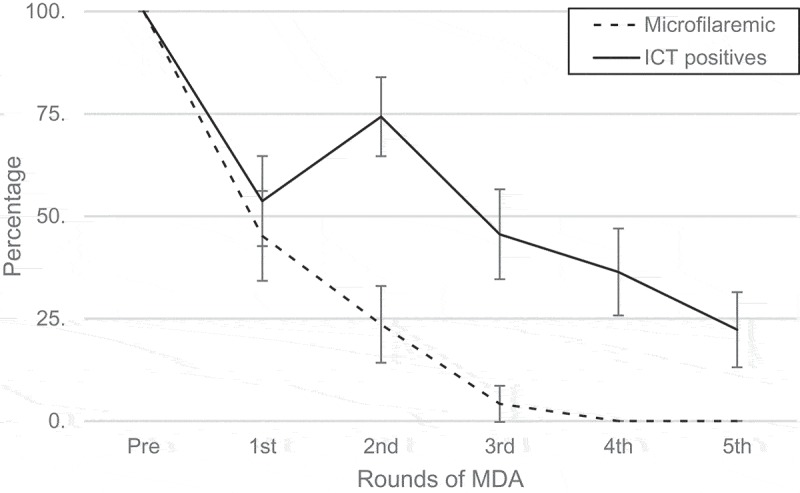

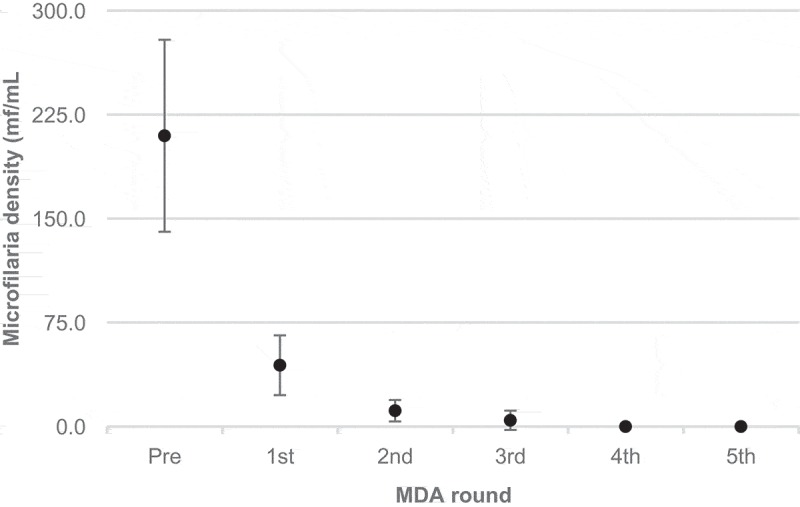

The Figures 1 to 4 depict the trend of filarial markers throughout five rounds of MDA in the study population (2007 to 2012). There was a progressive reduction in the proportion of mf positive individuals from the first annual round of MDA, which reached zero by the fourth dose. There was a marked decline (44.6%) in the proportion of CFA positives detected by POCT-ICT after the first dose, followed by an increase of around 25% after the second dose, after which the downward trend continued from the third dose. The overall reduction of POCT-ICT positive individuals was 78.1% after five doses of MDA. By comparison, mf density as assessed by QMFF demonstrated that the parasitic load declined sharply after the first dose of MDA, and microfilaraemia clearance was achieved after the third dose (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Frequency of microfilaraemic (Quantification microfilaria by filtration) and ICT positives according to rounds of MDA. Error bars represent 95% CI.

Figure 2.

Microfilariae density means (microfilaria quantification by filtration) according to rounds of MDA. Error bars represent 95% CI.

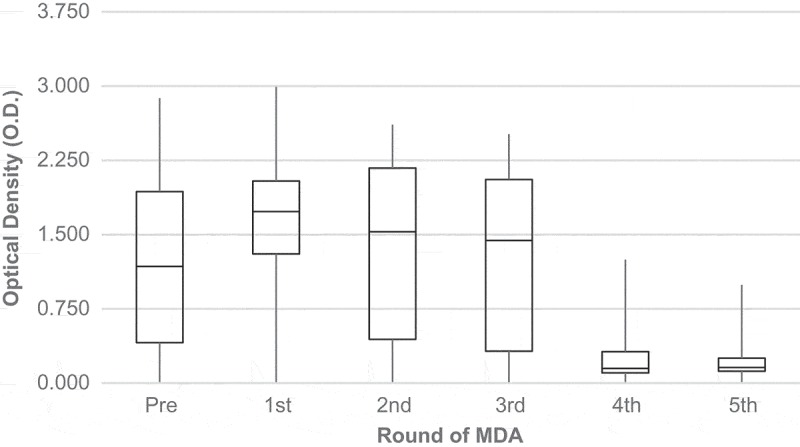

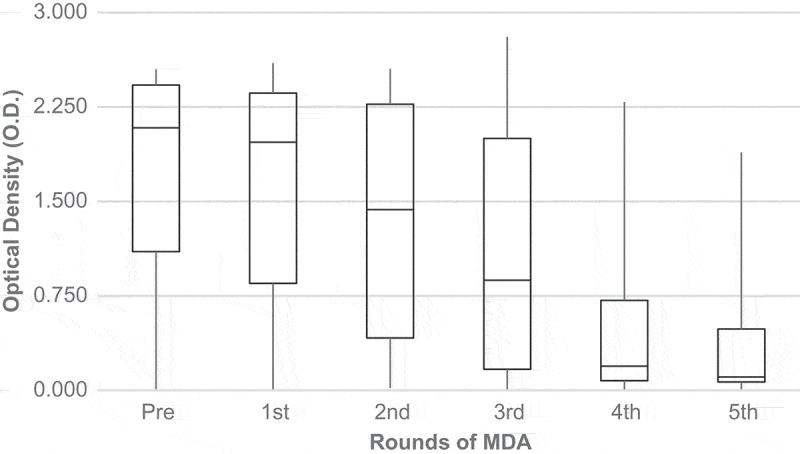

The CFA titres by Og4C3 remained relatively stable until the third dose of MDA, but increased slightly after the first dose. After the third dose, CFA levels were drastically reduced. Median CFA titres pre-MDA were 7.117 OD and reached 1.715 OD by the fourth dose (Figure 3). A marked trend of Filarial antibodies (IgG4) titre reduction was observed from the second round of MDA (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Medians of filarial antigenemia (Og4C3-ELISA) according to rounds of MDA.

Figure 4.

Medians of filarial antibodies (Bm14) according to rounds of MDA.

The GEE analysis showed a statistically significant reduction in all filarial laboratory markers during MDA among the participants (Table 2). The analysis showed that the probability of remaining positive by QMFF and POCT-ICT declined 70% and 46%, respectively, after each round of MDA. The annual reduction rate of mf density was 82% among microfilaraemic individuals.

Table 2.

Generalized Estimating Equation models to assess the Kinetics of LF markers according duration of MDA (in years) and number of MDA doses taken in the cohort of infected individuals. Olinda, Brazil, 2007–2012.

| LF markers | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| MF positives by Filtration (%) | OR (95%CI) a | |

| Time trend (per year of treatment) | 0.30 (0.25; 0.37) | <0.001 |

| Positives by POC-ICT (%)a | ||

| Time trend (per year of treatment) | 0.54 (0.50; 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Microfilariae density by QMFF*(mf/mL) | RR (95%CI)b | |

| Time trend (per year of treatment) | 0.18 (0.14; 0.24) | <0.001 |

| CFA** by Og4C3 (Optical Density) | β (95%CI)c | |

| Time trend (per year of treatment) | −0.290 (−0.314; −0.265) | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.006 (0.001; 0.011) | 0.031 |

| Antifilarial antibodies by BM14 (Optical Density) | ||

| Time trend (per year of treatment) | −0.303 (−0.330; −0.275) | <0.001 |

| Female | −0.272 (−0.483.; −0.061) | 0.011 |

*QMFF: Quantification MF by filtration **CFA: Circulating Filarial Antigen

aOdds Ratio estimated by logistic regression bRate Ratio estimated by negative binomial regression cAdjusted β parameters by linear regression model

As for CFA, the analysis demonstrated that the number of rounds of MDA (years of treatment) and age were independent factors associated with the level of antigenaemia by the Og4C3 test. The adjusted analysis indicated an annual mean reduction of filarial antigenaemia by Og4C3 of 0.290 OD. Conversely, Og4C3 titres increased with age; although this increase significant it was subtle (0.006, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.011).

Regarding IgG4- specific antibody by the Bm14 test, GEE analysis indicated a negative association between the duration of MDA and gender. According to the final model, annual mean reduction of IgG4 antibody titres was 0.303 OD (95% CI −0.330, −0.275) and was more pronounced in women than in men (p = 0.011).

After five rounds of MDA, a total of 30, nine, and 65 participants, respectively, remained positive by POCT-ICT, Og4C3 and Bm14. The mean ages of these individuals ranged from 22 to 29 years depending on the test. For all three tests, no statistically significant differences in the proportion of positives were observed by sex. Among the 30 participants that were CFA positive by POCT-ICT, four were also positive by Og4C3. A total of 70% (21/30) positive by POCT-ICT, 77% (7/9) positive by Og4C3 and 77% (50/65) positive by Bm14 had taken at least four doses of DEC.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the effectiveness of annual doses of MDA with DEC alone on filarial infection (mf, CFA and antifilarial antibodies) in Brazil since the implementation of the National Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis in 1997 [7]. Our results demonstrated a marked reduction in mf, CFA and antifilarial antibodies levels in a cohort of W. bancrofti infected individuals after repeated rounds of DEC, providing evidence of the effectiveness of DEC alone in the interruption of LF transmission in endemic areas of Brazil.

There was a marked reduction in both the proportion of mf positive individuals and parasitic load in the first three years of MDA and the total clearance of mf after the third round of MDA in our study population. These results are in accordance with previous studies conducted by Simonsen et al [25] and Tisch et al [26] that evaluated the effectiveness of MDA with DEC alone or DEC plus IVM in endemic areas of Tanzania (Africa) and Papua New Guinea, respectively. Therefore, our data reinforce the evidence that a four-year period of annual doses of MDA with DEC associated with >80% coverage should be sufficient for mf clearance and, consequently, the interruption of LF transmission in endemic areas.

Though a significant reduction in CFA by Og4C3-ELISA and POCT-ICT were observed, these markers did not disappear until the last year of follow-up, as observed for mf. Similar results were reported in several follow-up studies previously conducted in different endemic areas [14,16,27,28], which has been attributed to the limited effect of DEC on adult worms. Although the mechanism of DEC action in human filariae and other nematodes is unclear [28], studies have demonstrated a partial macrofilaricidal (around 50% [26,29,30]) and strong microfilaricidal effect in the first hours after administration of DEC [31]. This inability of serological methods to differentiate current from past infection limits its use as a diagnostic tool to evaluate the impact of MDA on LF transmission in endemic areas [32]. CFA titres by Og4C3 increased slightly with age in the study population. This result may be explained by higher parasitic loads usually observed in older when compared to younger populations [23], which may also be reflected in CFA levels.

An increase in the proportion of POCT-ICT positives was observed in the first round of MDA, which was followed by a steady and significant decline in subsequent rounds. This finding may be explained by the fact that POCT-ICT is an observer-dependent test carried out in the field, where conditions are less controlled than in the laboratory. However, although a high percentage of individuals maintained POCT-ICT (about 20%) positivity at end of follow up (five years), there was a significant decline in the proportion of CFA positive individuals during follow-up periods. A longer follow up period would be ideal, considering evidence that the CFA usually declines slower than mf and may persist for a longer period (e.g., after the fifth or sixth doses of MDA) [16,23,33].

Antifilarial antibody (Bm14) levels remained constant in the first two rounds and steadily declined until the fifth round of MDA, and this reduction was statistically significant. Moreover, GEE analysis demonstrated that the rate of antibody decline was more pronounced among women than in men. A previous study also reported higher levels of IgG4 specific antibodies in men than in women [13]. These observations may be related to differences in biological factors or behaviour in between the sexes.

Surprisingly, the decline of antibodies was most striking after the third dose, coinciding with mf clearance in the study population. The constant reduction in the antifilarial antibodies levels in populations which underwent MDA has been observed in several studies [16,26,33] and has been interpreted as the reduction or absence of population exposure to infective mosquito bites after MDA. For that reason, it has been recommended to assess LF transmission in areas with active elimination programs [26]. Therefore, our result suggest that the Bm14 test can be a useful diagnostic tool either as a marker of exposure to LF infection (L3 infective larvae) or persistence of LF transmission in populations undergoing MDA [14,34].

In summary, this study provides evidence that MDA with DEC alone can be effective after four annual doses, and seems sufficient to interrupt LF transmission in the endemic areas if coverage is sufficiently high (≥80%). This assumption is reinforced by the sharp decrease of antifilarial antibodies (Bm14) after three rounds of MDA. Our data also suggests that the Bm14 test can be a valuable diagnostic tool for monitoring and surveillance of Bancroftian filariasis in endemic areas undergoing MDA.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz/Fundação para o Desenvolvimento Tecnológico em Saúde - Vice-Presidência de Pesquisa e Laboratórios de Referência [FIOCRUZ/FIOTEC/VPPLR-002-LIV11-2-1, FIO-15-2-2 Project].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Center of Lymphatic Filariasis (NCLF/IAM/FIOCRUZ) in Recife and the Education and Health Departments of the City of Olinda for their support of the laboratory procedures and the field work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Ottesen EA, Duke BO, Karam M, et al. Strategies and tools for the control/elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75(6):491–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].WHO Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014;89(38):409–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].WHO Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: progress report, 2015. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016;91(39):441–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].WHO Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis meeting of the international task force for disease eradication. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92(9/10):97–116.28262010 [Google Scholar]

- [5].WHO Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: monitoring and epidemiological assessment of mass drug administration. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2011. p. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- [6].WHO Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;37(87):345–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].NHF. National Health Foundation National epidemiology center. [Elimination program of lymphatic filariasis in the Americas]. Bol Epidemiol. 1997;1(6):12. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Critchley J, Addiss D, Gamble C, et al. Albendazole for lymphatic filariasis international filariasis review group. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;19(4):CD003753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rizzo JA, Belo C, Lins R, et al. Children and adolescents infected with Wuchereria bancrofti in greater recife, Brazil: a randomized, year-long clinical trial of single treatments with diethylcarbamazine or diethylcarbamazine-albendazole. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007;101(5):423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ramzy RMR, El Stouhy M, Helmy H, et al. Effect of yearly mass drug administration with diethylcarbamazine and albendazole on bancroftian filariasis in Egypt: a comprehensive assessment. Lancet. 2006;367(9527):992–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bockarie MJ, Tavul L, Ibam I, et al. Efficacy of single-dose diethylcarbamazine compared with diethylcarbamazine combined with albendazole against Wuchereria bancrofti infection in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(1):62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ramaiah KD, Vanamail P, Yuvaraj J, et al. Effect of annual mass administration of diethylcarbamazine and albendazole on bancroftian filariasis in five villages in south India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105(8):431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lau CL, Won KY, Becke L, et al. Seroprevalence and spatial epidemiology of lymphatic filariasis in American Samoa after successful mass drug administration. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;11(8):e3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Helmy H, Weil GJ, Ellethya AST, et al. Bancroftian filariasis: effect of repeated treatment with diethylcarbamazine and albendazole on microfilaraemia, antigenaemia and antifilarial antibodies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(7):656–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Simonsen PE, Pedersen EM, Rwegoshora RT, et al. Lymphatic filariasis control in Tanzania: effect of repeated mass drug administration with ivermectin and albendazole on infection and transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(6):e696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wamaea CN, Njenga SM, Ngugi BM, et al. Evaluation of effectiveness of diethylcarbamazine/albendazole combination in reduction or Wuchereria bancrofti infection using multiple infection parameters. Acta Trop. 2011;120(1):S33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].MH Ministry of Health Secretariat of health surveillance. [Guidelines for surveillance and elimination of lymphatic filariasis]. Brasilia: Ministry of Health. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [18].IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). censos demográficos, 2010(Acessed 2016 October30). Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br/censo

- [19].Braga C, Ximenes RA, Albuquerque M, et al. Evaluation of a social and environmental indicator used in the identification of lymphatic filariasis transmission in urban centers. Cad De Saúde Pública. 2001;17(5):1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Braga C, Dourado MI, Ximenes RAA, et al. Field evaluation of the whole blood immunochromatografic test for rapid bancroftian filariasis diagnosis in the northeast of Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2003;45(3):125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rocha A, Marcondes M, Nunes JRV, et al. Elimination and control of lymphatic filariasis program: a partnership between the department of health in Olinda, Pernambuco state, Brazil and the National Center of Lymphatic Filariasis. Rev Patol Trop. 2010;39(3):233–249. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lima AW, Medeiros Z, Santos ZC, et al. Adverse reactions following mass drug administration with diethylcarbamazine in lymphatic filariasis endemic areas in the Northeast of Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45(6):745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rocha A, Braga C, Belém M, et al. Comparison of tests for the detection of circulating filarial antigen (Og4C3-ELISA and AD12-ICT) and ultrasound in diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis in individuals with microfilariae. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(4):621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Weil GJ, Curtis KC, Fischer PU, et al. A multicenter evaluation of a new antibody test kit for lymphatic filariasis employing recombinant Brugia malayi antigen Bm-14. Acta Trop. 2011;120(1):S19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MDB, et al. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(4):364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tisch DJ, Bockarie MJ, Dimber Z, et al. Mass drug administration trial to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in Papua New Guinea: changes in microfilaremia, filarial antigen and Bm14 antibody after cessation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78(2):289–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bockarie MJ, Deb RM.. Elimination of lymphatic filariasis: do we have drugs to complete the job? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23(6):617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Freedman DO, Plier DA, Almeida AB, et al. Effect os aggressive prolonged diethylcarbamazine therapy on circulating antigen levels in bancroftian filariasis. Trop Med Inter Health. 2001;6(1):37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Melrose WD. Chemoterapy for lymphatic filariasis: progress but not perfection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2003;1(4):571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Norões J, Dreyer G, Santos A, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of diethylcarbamazine on adult Wuchereria bancrofti in vivo. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91(1):78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Buxton SK, Robertson AP, Martin RJ. Diethylcarbamazine increases activation of voltage-activated potassium (SLO-1) currents in Ascaris suum and potentiates effects of emodepside. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014November20;8(11):e3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Huppatz C, Durrheim D, Lammie P, et al. Eliminating lymphatic filariasis– the surveillance challenge. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(3):292–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Weil GJ, Kastens W, Susapu M, Laney SJ, Williams SA, King CL, et al The impact of repeated rounds of mass drug administration with diethylcarbamazine plus albendazole on bancroftian filariasis in Papua New Guinea. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(12):e344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Simonsen PE, Magesa SM, Meyrowitsch DW, et al. The effect of eight half-yearly single dose treatments with DEC on Wuchereria bancrofti circulating antigenaemia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99(7):541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]