Abstract

Tau is a developmentally regulated axonal protein that stabilizes and bundles microtubules (MTs). Its hyperphosphorylation is thought to cause detachment from MTs and subsequent aggregation into fibrils implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. It is unclear which tau residues are crucial for tau-MT interactions, where tau binds on MTs, and how it stabilizes them. We used cryo–electron microscopy to visualize different tau constructs on MTs, and computational approaches to generate atomic models of tau-tubulin interactions. The conserved tubulin-binding repeats within tau adopt similar extended structures along the crest of the protofilament, stabilizing the interface between tubulin dimers. Our structures explain the effect of phosphorylation on MT affinity and lead to a model of tau repeats binding in tandem along protofilaments, tethering together tubulin dimers and stabilizing polymerization interfaces.

Microtubules (MTs) are formed by the assembly of αβ-tubulin dimers into protofilaments (PFs) that associate laterally into hollow tubes. MTs are regulated by MT-associated proteins (MAPs), including “classical” MAPs such as MAP-2, MAP-4, and tau that are critical to neuronal growth and function. Tau constitutes over 80% of neuronal MAPs, stabilizes and bundles axonal MTs (1), and is developmentally regulated (2). Full-length adult tau is intrinsically disordered and includes a projection domain, a MT-binding region of four imperfect sequence repeats (R1–4), and a C-terminal domain (3) (Fig. 1A; notice that the precise definition of the repeats has not always been consistent in the literature and the one displayed in the figure is justified by the structural findings in this study). Different repeats bind to and stabilize MTs (4, 5), with affinity and activity increasing with the number of repeats (5, 6). Neurodegenerative tauopathies, including Alzheimer’s disease, develop when mutated (7, 8) or abnormally phosphorylated tau loses affinity for MTs (9–11) and forms filamentous aggregates called neurofibrillary tangles. While we know the structure of amyloid tau fibrils (12), the physiological conformation of MT-bound tau remains controversial (13–17). Here we present atomic models of MT-bound tau using a combination of single-particle cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and Rosetta modeling.

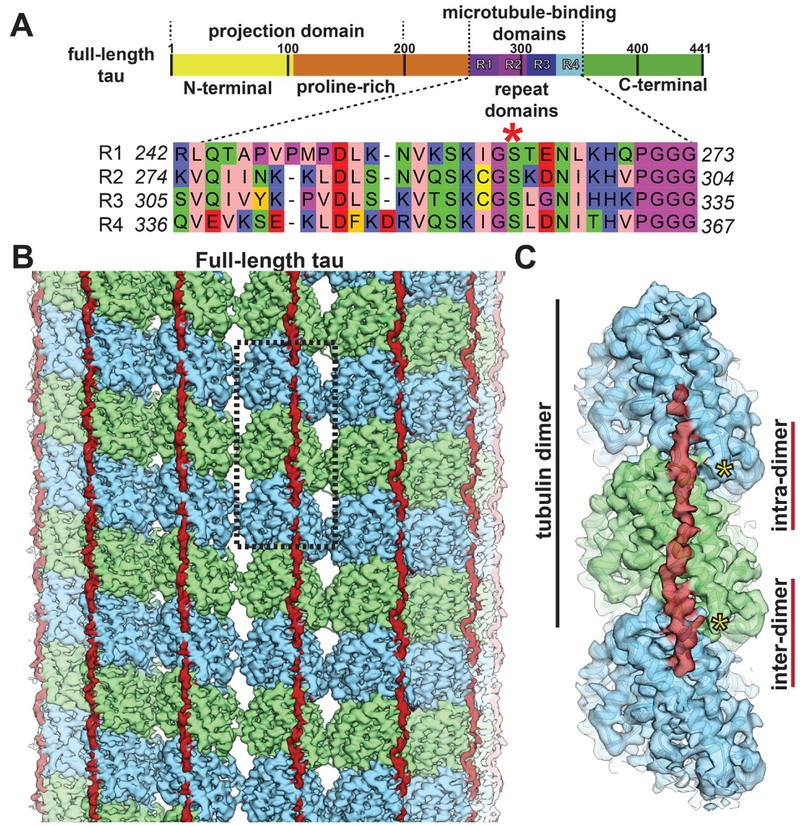

Fig. 1. Tau binding to microtubules.

(A) Schematic of tau domain architecture and assigned functions. The MT-binding domain of four repeats is defined as residues 242–367. Inset shows the sequence alignment of the four repeat sequences, R1–4, that make up the repeat domain. Ser262 is marked by the red asterisk. (B) Cryo-EM density map (4.1 Å overall resolution) of a MT decorated with full-length tau. Tau (red) appears as a nearly continuous stretch of density along PFs (α-tubulin in green, β-tubulin in blue). (C) The footprint of a continuous stretch of tau spans over three tubulin monomers, binding both across intra- and inter-dimer tubulin interfaces (only one repeat of tau is shown for clarity). Position of the C-termini of tubulin indicated with yellow asterisks.

We used cryo-EM to visualize MTs in the presence of an excess of different tau constructs (figs. S1 and S2). The cryo-EM structure of dynamic MTs (without stabilizing drugs or non-hydrolizable GTP analogs) assembled with full-length tau (overall resolution of 4.1 Å) (fig. S2C) shows tau as a narrow, discontinuous density along each PF (Fig. 1B), following the ridge on the MT surface defined by the H11-H12 helices of α- and β-tubulin, and adjacent to the site of attachment of the C-terminal tubulin tails (Fig. 1C) that are important for tau affinity (18, 19). This location is consistent with a previous, low-resolution cryo-EM study (16). To test an alternatively proposed tau binding site on the MT interior (17), we added tau to pre-formed MTs or to polymerizing tubulin, both in the absence of Taxol, but never saw tau density on the MT luminal surface.

We also examined two N- and C-terminally truncated tau constructs including either all four repeats (4R) or just the first two (2R) (fig. S2, A and B) (note that we refer to the construct containing 4 repeats as 4R, whereas the sequence of the 4th repeat is referred to as R4). Both reconstructions (4.8 Å and 5.6 Å, respectively) (fig. S2C) and that of full-length tau were indistinguishable at the resolutions obtained. In all three cases, the length of the tau density corresponds to an extended chain of ~27 amino acids, with a weak connecting density that would accommodate another 3–4 residues, adding up to the length of one repeat (31/32 amino acids).

The lower resolution of tau (4.6–6.5 Å) relative to tubulin (4.0–4.5 Å) in our reconstructions (fig. S3) could be due to substoichiometric binding (unlikely due to the excess of tau), flexibility, and/or differences between the repeats. Thus, we pursued the structure of a synthetic tau construct with four identical copies of R1 (R1×4) (Fig. 2) and reached an overall resolution of 3.2 Å (Fig. 2A and fig. S2C), with local resolution for tau between 3.7 Å and 4.2 Å (fig. S3). In this map the best resolved region of tau approached the resolution of surface regions of tubulin. Again, tau appears as regularly spaced segments separated by more discontinuous density, as expected from the alternation of more tightly bound segments interspersed with more mobile regions (5, 20). A poly-alanine model accommodating 12 residues was built into the best-resolved segment of the R1×4 tau density at the inter-dimer interface,.

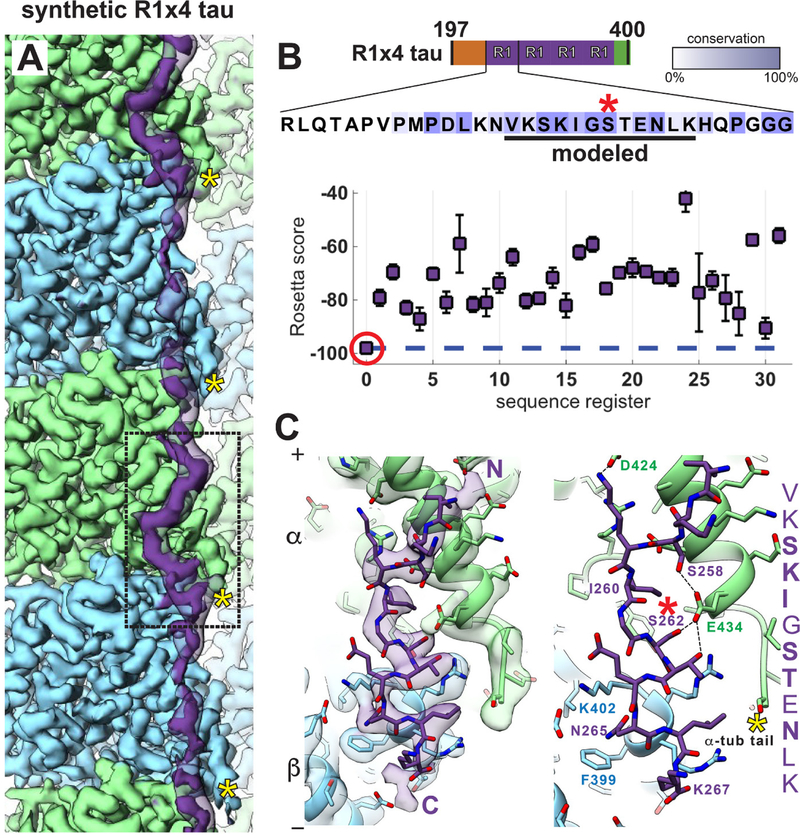

Fig. 2. Near-atomic resolution reconstruction of synthetic R1×4 tau on microtubules.

(A) In the 3.2 Å cryo-EM reconstruction of tau-bound MTs, the best-ordered segment of tau is bound at the interface between tubulin dimers (boxed) (lower threshold density for tau is shown in transparency). (B) Rosetta modeling reveals a single energetically preferred sequence register (red circle) for the best-ordered tau region, corresponding to a conserved (underlined) 12-residue stretch of residues within the R1 repeat sequence. All Rosetta simulations were repeated until convergence (100 models per register). Intensity of colored boxes indicates extent of conservation among tau homologs. S262 is indicated with red asterisk in (B) and (C). (C) Atomic model of tau and tubulin, with (left) and without (right) the density map, showing the interactions over the inter-dimer region. C-termini of tubulin indicated with yellow asterisks in (A) and (C).

Due to the lack of large sidechains or secondary structure, we used Rosetta (21) as an unbiased approach to assess different tau repeat sequence registers (see methods in supplementary materials). A single register and conformation was favored, both energetically and based on fit to density, and included amino acids 256–267 (VKSKIGSTENLK), the most conserved segment among tau repeats (Fig. 2B). An alternative, more aggressive refinement protocol (22), which introduces more structural variability during the refinement procedure, converged to the same sequence and structure (fig. S4). This common solution corresponds to a 12-residue sequence contained within an 18 aa fragment that is sufficient to promote MT polymerization (4, 23). Furthermore, the inferred interactions are consistent with sequence conservation among classical MAPs beyond tau (fig. S5), with conserved residues contributing critical tubulin interactions within our model (Fig. 2C). Ser258 and Ser262 form hydrogen bonds with α-tubulin Glu434. Phosphorylation of the universally conserved Ser262 (fig. S5) strongly attenuates MT binding (24) and is a marker of Alzheimer’s disease (25). Our structure now explains how its phosphorylation disrupts tautubulin interactions. Although Thr263 is also positioned to hydrogen-bond with Glu434, hydrophobic substitutions are tolerated at this position (fig. S5), indicating that this interaction may not be as essential. The conserved Lys259 is positioned to interact with an acidic patch on α-tubulin formed by Asp424, Glu420, and Glu423 (Fig. 2C). Ile260, conserved in hydrophobic character across all R1 sequences (fig. S5), is buried within a hydrophobic pocket formed by α-tubulin residues Ile265, Val435, and Tyr262 at the inter-dimer interface (Fig. 2C). Asn265, universally conserved amongst repeats of classical MAPs (fig. S5), forms a stabilizing intramolecular hydrogen bond within the type II’ β-turn formed by residues 263–266. Finally, Lys267 is positioned to interact with the acidic α-tubulin C-terminal tail, and its basic character is conserved (Fig. 2C and fig. S5).

The tau density beyond this 12-residue stretch is very weak (Fig. 2A), indicating that 242–255 lacks ordered interactions with tubulin. This region of R1 is rich in prolines, but shows a distinct, conserved hydrophobic pattern in both R2 and R3 (Fig. 1A and fig. S5). Since other tau repeats might form additional interactions with the MT surface, we also obtained a cryo-EM reconstruction using a synthetic tau construct containing four copies of repeat R2 (R2×4). The R2×4-MT reconstruction, at an overall resolution of 3.9 Å (Fig. 3A and fig. S2C), was similar to R1×4, especially at the inter-dimer tubulin interface (Fig. 3A and fig. S6A), but had additional tau density along the surface of β-tubulin. We could model a backbone stretch of 27 residues into the R2×4 tau density, spanning three tubulin monomers, with a length close to the tubulin dimer repeat in the MT lattice (~80 Å). As for R1, we discovered a single, strongly preferred register and conformation for R2 using Rosetta (Fig. 3B), regardless of chosen simulation parameters. Our analyses of R1 and R2 resulted in equivalent sequence registers and virtually identical atomic models at the inter-dimer interface (Fig. 3, C and D), with conserved residues making critical contacts with tubulin. For two non-conserved positions, Cys291(R2) versus Ile260(R1), and Lys294(R2) versus Thr263(R1) (Fig. 3C), the nature of the interactions are preserved [free cysteines demonstrate strong hydrophobic character (26) and Lys294 likely interacts with the acidic C-terminal tail (Fig. 3, E and G)]. The identical sequence register and atomic details from two independent maps, underscores the robustness of our solution and provides high confidence in the accuracy of our atomic models. The sequence assignment is further supported by previous gold-labeling experiments on the binding of MAP2 to MTs (fig. S6, B to D).

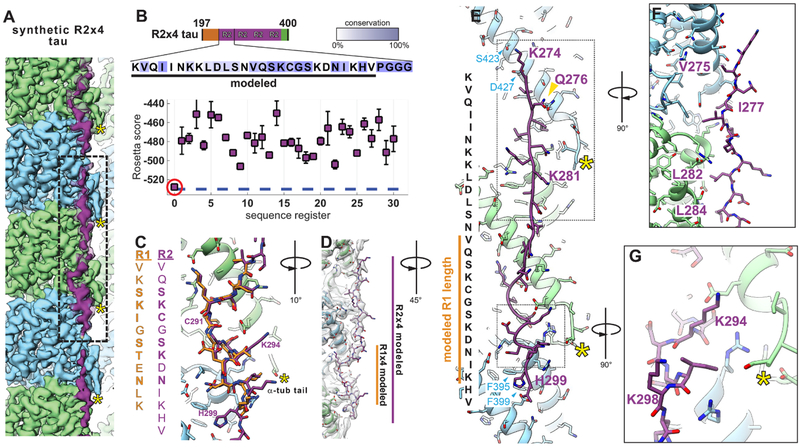

Fig. 3. High-resolution reconstruction of synthetic R2×4 tau on microtubules.

(A) The (3.9 Å) cryo-EM reconstruction of R2×4 is highly similar to that of R1×4, but reveals a longer stretch of ordered density for tau along the MT surface (lower threshold density for tau is shown in transparency). (B) Rosetta modeling supports a sequence register (red circle) for the R2 sequence binding to tubulin equivalent to that for R1 and shown in Fig. 2. All Rosetta simulations were repeated until convergence (100 models per register). (C) Major tau-tubulin interactions at the inter-dimer cleft are highly similar between the R1 (shown in goldenrod for easier visualization) and R2 (purple) sequences. (D) Extending the model to account for the additional density reveals an almost entire repeat of tau, spanning three tubulin monomers (centered on α-tubulin and contacting β- tubulin on either side) with an overall length of ~80 Å (the approximate length of a tubulin dimer). C-termini of tubulin indicated with yellow asterisks in (A), (C), (E), and (G). (E) Atomic model of the R2 repeat, shown along with the corresponding R2 sequence. The position of the previously studied gold-labeled residue in MAP2 at the equivalent position based on homology (16) is indicated with a gold arrowhead and is in very good agreement with our model (see also fig. S6). Boxed out regions show: (F) the hydrophobic packing of tau residues on the MT surface (see also fig. S8), and (G) the positioning of two R2 lysines with potential interactions with the α- tubulin acidic C-terminal tail.

Our R2×4 model includes the peptide VQIINKK (not conserved in R1), which as an isolated peptide can bind MTs (6) and promote MT polymerization (23). This R2 peptide localizes to the intra-dimer interface and is sufficiently close to interact with the β-tubulin C-terminal tail (Fig. 3, E and F). While tau and kinesin make distinct contacts with tubulin, their MT binding sites partially overlap (fig. S7), which explains why tau binding interferes with kinesin attachment to MTs (27). Residues Val275, Ile277, Leu282 and Leu284 (Fig. 3F) are buried against the MT-surface and tolerate only conservative hydrophobic substitutions in R2, R3 and R4 (fig. S8). Lys274 and Lys281 are crucial for tau-MT binding (6). In our model, Lys274 is close to an acidic patch on the MT formed by Asp427 and Ser423 in β-tubulin (Fig. 3, E and G), while Lys281 is well positioned to interact with the β-tubulin C-terminal tail (Fig. 3E). Finally, the highly conserved His299 in R2 is buried in a cleft formed by β-tubulin residues Phe395 and Phe399 (Fig. 3, C and E).

Although we could model most of the residues in a tau repeat, we could not clearly visualize the highly conserved PGGG motif, which would correspond to the region connecting the modeled segments. Figure S9 shows a model of consecutive R1 and R2 binding, based on the atomic models of both repeats connected by an extended PGGG segment, placed into the full-length tau experimental map. The similarity among repeats, specially R2 and R3, and the geometry of their binding to tubulin, strongly supports a tandem binding mode of the four repeats along a PF (fig. S8 shows the hydrophobic interactions between these tau repeats and tubulin). Comparison of our microtubule-bound tau structures for R1 and R2 with that of fibrillary tau for R3 and R4 shows that while they are globally very different, they share some similarities in local structure, especially in the conserved, hydrophobic regions (fig. S10).

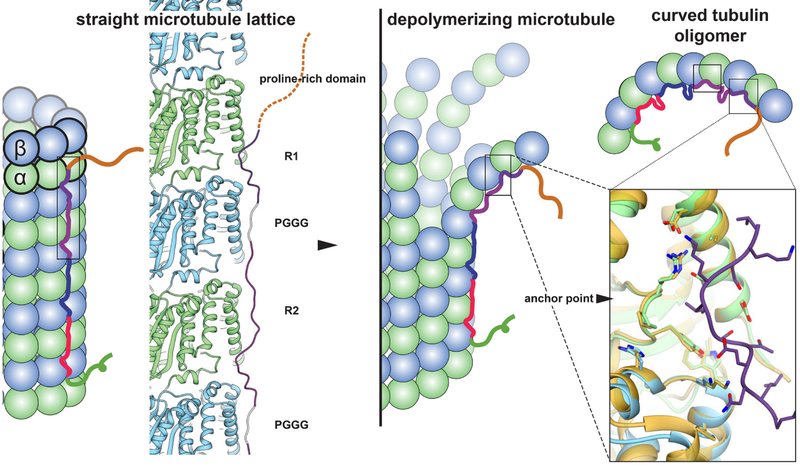

In summary, our MT-tau structures lead to a model in which each tau repeat has an extended conformation that spans both intra- and inter-dimer interfaces, centered on α-tubulin and connecting three tubulin monomers. Extensive modeling on two independently determined reconstructions complemented the experimental map and led to a proposed model of the repeat structure and MT interactions that is supported by sequence conservation and explains previous biochemical observations. The universally conserved Ser262, a major site of phosphorylation, is critically involved in tight contacts with tubulin near a polymerization interface, explaining how its modification interferes with tubulin binding and MT stabilization. The major tau binding site corresponds to the ‘anchor point’ (28), a tubulin region that is practically unaltered during the structural changes accompanying nucleotide hydrolysis or when comparing assembled and disassembled states of tubulin (Fig. 4, right). This finding explains how tau promotes the formation of tubulin rings (29) and co-purifies with MTs through tubulin assembly-disassembly cycles. Our structures suggest that all four tau repeats are likely to associate with the MT surface in tandem, through adjacent tubulin subunits along a PF. This modular structure explains how alternatively spliced variants can have essentially identical interactions with tubulin, but different affinity based on the number of repeats present. The tandem binding of tau along a PF explains how tau promotes both MT polymerization and stabilization by tethering multiple tubulin dimers together across longitudinal interfaces (Fig. 4, left). This mode of interaction explains the reduced off-rate of tubulin dimers in the presence of tau (30) that results in reduced catastrophe frequencies (transitions from assembly to disassembly of MTs) and the loss of dynamicity caused by tau and other classical MAPs. Our study does not discard the possibility that other structural elements within tau could be involved in additional tubulin interactions, especially if engaging with the unstructured C-terminal tubulin tails. Such potential contacts could contribute to inter-PF and/or inter-MT interactions.

Fig. 4. Model of full-length tau binding to microtubules and tubulin oligomers.

Our structural data leads to a model of tau interaction with MTs in which the four repeats bind in tandem along a PF. Notice that we do not observe strong density for the region that would correspond to the PGGG motif, which is modeled in gray for illustrative purposes and must be highly flexible. Tau binding at the inter-dimer interface, interacting with both α- and β-tubulin, promotes association between tubulin dimers. The tau binding site is also the location of the previously identified “anchor point” [right-most box, gold is bent tubulin, PDB code 4I4T (31), and blue/green is straight tubulin, PDB code 3JAR (28)], and thus tau-tubulin interactions are unlikely to change significantly with protofilament peeling during disassembly (center) or when bound to small, curved tubulin oligomers (top right).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Chintangal and P. Tobias for computational support. We also thank P. Grob and D. Toso for EM support. We thank B. Greber for help with initial model building. Funding: This work was funded by a BWF collaborative research travel grant (008185) (E.H.K.) and NIHGMS grants GM123089 (F.D.) and GM051487 (E.N.). E.N. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. Author contributions: Conceptualization, E.H.K., N.M.A.H., and E.N.; methodology, E.H.K., N.M.A.H., F.D., and E.N.; investigation, E.H.K., N.M.A.H., F.D., and E.N.; writing (original draft), E.H.K. and E.N.; writing (review and editing), all authors; funding acquisition, E.N.; resources, S.P.; supervision, E.N. and K.H.D. Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests. Data and materials availability: Atomic models are available through the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accessions codes 6CVJ (R1×4) and 6CVN (R2×4); all cryo-EM reconstructions are available through the EMDB with accession codes EMD-7520 (2Rtau), EMD-7523 (4Rtau), EMD-7522 (full-length tau), EMD-7769 (R1×4-tau), and EMD-7771 (R2×4-tau).

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Conde C, Cáceres A, Microtubule assembly, organization and dynamics in axons and dendrites. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 10, 319–332 (2009). doi: 10.1038/nrn2631 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosik KS, Orecchio LD, Bakalis S, Neve RL, Developmentally regulated expression of specific tau sequences. Neuron 2, 1389–1397 (1989). doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90077-9 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himmler A, Drechsel D, Kirschner MW, Martin DW Jr., Tau consists of a set of proteins with repeated C-terminal microtubule-binding domains and variable N-terminal domains. Mol. Cell. Biol 9, 1381–1388 (1989). doi: 10.1128/MCB.9.4.1381 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ennulat DJ, Liem RK, Hashim GA, Shelanski ML, Two separate 18-amino acid domains of tau promote the polymerization of tubulin. J. Biol. Chem 264, 5327–5330 (1989). Medline [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butner KA, Kirschner MW, Tau protein binds to microtubules through a flexible array of distributed weak sites. J. Cell Biol 115, 717–730 (1991). doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.717 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goode BL, Feinstein SC, Identification of a novel microtubule binding and assembly domain in the developmentally regulated inter-repeat region of tau. J. Cell Biol 124, 769–782 (1994). doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.769 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski J, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JBJ, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P, Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393, 702–705 (1998). doi: 10.1038/31508 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong M, Zhukareva V, Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, Wszolek Z, Reed L, Miller BI, Geschwind DH, Bird TD, McKeel D, Goate A, Morris JC, Wilhelmsen KC, Schellenberg GD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science 282, 1914–1917 (1998). doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1914 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso AC, Zaidi T, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Role of abnormally phosphorylated tau in the breakdown of microtubules in Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 91, 5562–5566 (1994). doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5562 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alonso AC, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Alzheimer’s disease hyperphosphorylated tau sequesters normal tau into tangles of filaments and disassembles microtubules. Nat. Med 2, 783–787 (1996). doi: 10.1038/nm0796-783 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustke N, Steiner B, Mandelkow E-M, Biernat J, Meyer HE, Goedert M, Mandelkow E, The Alzheimer-like phosphorylation of tau protein reduces microtubule binding and involves Ser-Pro and Thr-Pro motifs. FEBS Lett 307, 199–205 (1992). doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80767-B Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SHW, Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 547, 185–190 (2017). doi: 10.1038/nature23002 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eliezer D, Barré P, Kobaslija M, Chan D, Li X, Heend L, Residual structure in the repeat domain of tau: Echoes of microtubule binding and paired helical filament formation. Biochemistry 44, 1026–1036 (2005). doi: 10.1021/bi048953n Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li XH, Culver JA, Rhoades E, Tau binds to multiple tubulin dimers with helical structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 9218–9221 (2015). doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04561 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadavath H, Jaremko M, Jaremko Ł, Biernat J, Mandelkow E, Zweckstetter M, Folding of the Tau protein on microtubules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 54, 10347–10351 (2015). doi: 10.1002/anie.201501714 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Bassam J, Ozer RS, Safer D, Halpain S, Milligan RA, MAP2 and tau bind longitudinally along the outer ridges of microtubule protofilaments. J. Cell Biol 157, 1187–1196 (2002). doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201048 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kar S, Fan J, Smith MJ, Goedert M, Amos LA, Repeat motifs of tau bind to the insides of microtubules in the absence of taxol. EMBO J. 22, 70–77 (2003). doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg001 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chau MF, Radeke MJ, de Inés C, Barasoain I, Kohlstaedt LA, Feinstein SC, The microtubule-associated protein tau cross-links to two distinct sites on each alpha and beta tubulin monomer via separate domains. Biochemistry 37, 17692–17703 (1998). doi: 10.1021/bi9812118 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serrano L, Montejo de Garcini E, Hernández MA, Avila J, Localization of the tubulin binding site for tau protein. Eur. J. Biochem 153, 595–600 (1985). doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb09342.x Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadavath H, Hofele RV, Biernat J, Kumar S, Tepper K, Urlaub H, Mandelkow E, Zweckstetter M, Tau stabilizes microtubules by binding at the interface between tubulin heterodimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112, 7501–7506 (2015). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504081112 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Y, DiMaio F, Wang RY-R, Kim D, Miles C, Brunette T, Thompson J, Baker D, High-resolution comparative modeling with RosettaCM. Structure 21, 1735–1742 (2013). doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.005 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang RY, Song Y, Barad BA, Cheng Y, Fraser JS, DiMaio F, Automated structure refinement of macromolecular assemblies from cryo-EM maps using Rosetta. eLife 5, e17219 (2016). doi: 10.7554/eLife.17219 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panda D, Goode BL, Feinstein SC, Wilson L, Kinetic stabilization of microtubule dynamics at steady state by tau and microtubule-binding domains of tau. Biochemistry 34, 11117–11127 (1995). doi: 10.1021/bi00035a017 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biernat J, Gustke N, Drewes G, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Phosphorylation of Ser262 strongly reduces binding of tau to microtubules: Distinction between PHF-like immunoreactivity and microtubule binding. Neuron 11, 153–163 (1993). doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90279-Z Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasegawa M, Morishima-Kawashima M, Takio K, Suzuki M, Titani K, Ihara Y, Protein sequence and mass spectrometric analyses of tau in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. J. Biol. Chem 267, 17047–17054 (1992). Medline [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagano N, Ota M, Nishikawa K, Strong hydrophobic nature of cysteine residues in proteins. FEBS Lett. 458, 69–71 (1999). doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01122-9 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trinczek B, Ebneth A, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Tau regulates the attachment/detachment but not the speed of motors in microtubule-dependent transport of single vesicles and organelles. J. Cell Sci. 112, 2355–2367 (1999). Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang R, Alushin GM, Brown A, Nogales E, Mechanistic origin of microtubule dynamic instability and its modulation by EB proteins. Cell 162, 849–859 (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.012 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devred F, Barbier P, Douillard S, Monasterio O, Andreu JM, Peyrot V, Tau induces ring and microtubule formation from αβ-tubulin dimers under nonassembly conditions. Biochemistry 43, 10520–10531 (2004). doi: 10.1021/bi0493160 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinczek B, Biernat J, Baumann K, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Domains of tau protein, differential phosphorylation, and dynamic instability of microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 1887–1902 (1995). doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1887 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prota AE, Bargsten K, Zurwerra D, Field JJ, Díaz JF, Altmann K-H, Steinmetz MO, Molecular mechanism of action of microtubule-stabilizing anticancer agents. Science 339, 587–590 (2013). doi: 10.1126/science.1230582 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tennstaedt A, Pöpsel S, Truebestein L, Hauske P, Brockmann A, Schmidt N, Irle I, Sacca B, Niemeyer CM, Brandt R, Ksiezak-Reding H, Tirniceriu AL, Egensperger R, Baldi A, Dehmelt L, Kaiser M, Huber R, Clausen T, Ehrmann M, Human high temperature requirement serine protease A1 (HTRA1) degrades tau protein aggregates. J. Biol. Chem 287, 20931–20941 (2012). doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316232 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kellogg EH, Hejab NMA, Howes S, Northcote P, Miller JH, Díaz JF, Downing KH, Nogales E, Insights into the distinct mechanisms of action of taxane and non-taxane microtubule stabilizers from cryo-EM structures. J. Mol. Biol 429, 633–646 (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.01.001 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carragher B, Kisseberth N, Kriegman D, Milligan RA, Potter CS, Pulokas J, Reilein A, Leginon: An automated system for acquisition of images from vitreous ice specimens. J. Struct. Biol 132, 33–45 (2000). doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4314 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Mooney P, Zheng S, Booth CR, Braunfeld MB, Gubbens S, Agard DA, Cheng Y, Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat. Methods 10, 584–590 (2013). doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohou A, Grigorieff N, CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol 192, 216–221 (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ, EMAN2: An extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol 157, 38–46 (2007). doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grigorieff N, FREALIGN: High-resolution refinement of single particle structures. J. Struct. Biol 157, 117–125 (2007). doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.004 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egelman EH, A robust algorithm for the reconstruction of helical filaments using single-particle methods. Ultramicroscopy 85, 225–234 (2000). doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(00)00062-0 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alushin GM, Lander GC, Kellogg EH, Zhang R, Baker D, Nogales E, High-resolution microtubule structures reveal the structural transitions in αβ-tubulin upon GTP hydrolysis. Cell 157, 1117–1129 (2014). doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.053 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang R, Nogales E, A new protocol to accurately determine microtubule lattice seam location. J. Struct. Biol 192, 245–254 (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.09.015 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mastronarde DN, Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol 152, 36–51 (2005). doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache J-P, Verba KA, Cheng Y, Agard DA, MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K, Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 (2010). doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holm L, Sander C, Database algorithm for generating protein backbone and side-chain co-ordinates from a Cα trace: Application to model building and detection of co-ordinate errors. J. Mol. Biol 218, 183–194 (1991). doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90883-8 Medline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park H, Bradley P, Greisen P Jr., Liu Y, Mulligan VK, Kim DE, Baker D, DiMaio F, Simultaneous optimization of biomolecular energy functions on features from small molecules and macromolecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput 12, 6201–6212 (2016). doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00819 Medline [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.