Abstract

Background

There currently are no internationally recognised treatment guidelines for patients with advanced gastric cancer/gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (GC/GEJC) in whom two prior lines of therapy have failed. The randomised, phase III JAVELIN Gastric 300 trial compared avelumab versus physician’s choice of chemotherapy as third-line therapy in patients with advanced GC/GEJC.

Patients and methods

Patients with unresectable, recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic GC/GEJC were recruited at 147 sites globally. All patients were randomised to receive either avelumab 10 mg/kg by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 or irinotecan 150 mg/m2 on days 1 and 15, each of a 4-week treatment cycle); patients ineligible for chemotherapy received best supportive care. The primary end point was overall survival (OS). Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and safety.

Results

A total of 371 patients were randomised. The trial did not meet its primary end point of improving OS {median, 4.6 versus 5.0 months; hazard ratio (HR)=1.1 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.9–1.4]; P = 0.81} or the secondary end points of PFS [median, 1.4 versus 2.7 months; HR=1.73 (95% CI 1.4–2.2); P > 0.99] or ORR (2.2% versus 4.3%) in the avelumab versus chemotherapy arms, respectively. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) of any grade occurred in 90 patients (48.9%) and 131 patients (74.0%) in the avelumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively. Grade ≥3 TRAEs occurred in 17 patients (9.2%) in the avelumab arm and in 56 patients (31.6%) in the chemotherapy arm.

Conclusions

Treatment of patients with GC/GEJC with single-agent avelumab in the third-line setting did not result in an improvement in OS or PFS compared with chemotherapy. Avelumab showed a more manageable safety profile than chemotherapy.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02625623.

Keywords: PD-L1, avelumab, chemotherapy, gastric cancer, gastro-oesophageal junction cancer, phase III

Key Message

The phase III, randomised JAVELIN Gastric 300 trial is the first to compare an anti-PD-L1 antibody (avelumab) with chemotherapy in the third-line setting. The trial did not meet its primary end point of improving OS; however, avelumab had antitumour activity similar to chemotherapy in patients with GC/GEJC treated with two prior regimens for advanced disease, with a more favourable safety profile.

Introduction

Patients with newly diagnosed metastatic gastric cancer/gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (GC/GEJC) have poor prognosis, with median overall survival (OS) of ∼1 year; patients with previously treated metastatic GC/GEJC have even worse prognosis [1–4]. Chemotherapy remains the standard of care for advanced GC/GEJC and can prolong survival and improve quality of life compared with best supportive care (BSC); however, most chemotherapy regimens fail to provide substantial survival benefits [3, 4].

For patients with advanced GC/GEJC, first-line treatment with platinum and fluoropyrimidine is standard, with trastuzumab added for patients with HER2+ tumours [5–7]. Preferred second-line treatments include taxanes, irinotecan, or ramucirumab as monotherapy or in combination with paclitaxel [5, 6]. Although phase III data are lacking, third-line chemotherapy is widely utilised in patients in whom previous lines have failed, especially in Asia [8]. In the TAGS study, trifluridine/tipiracil improved OS [5.7 versus 3.6 months; HR =0.69 (95% CI 0.56–0.85); P = 0.0003] compared with placebo as third-line or later therapy for advanced GC [9]. Currently, there are no standard, internationally recognised guidelines for third-line therapy for patients with advanced GC/GEJC, underscoring the need for effective therapies with acceptable safety profiles [5, 6, 8, 10].

GC/GEJC is associated with immune system evasion and overexpression of immune checkpoint proteins, providing the rationale for immunotherapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy [11–14]. Elevated expression of PD-L1 has been reported in up to 65% of GC/GEJC and is associated with specific subtypes of gastric adenocarcinoma and tumours with high mutational burden [11–14]. However, there is currently no consensus on the role of PD-L1 expression as a prognostic biomarker in advanced GC [15].

Initial trial results have demonstrated the clinical activity of immunotherapy in the third-line setting or beyond in patients with advanced GC/GEJC in single-arm studies or randomised trials using placebo as the comparator. Pembrolizumab was granted accelerated approval in the USA for patients with PD-L1+ GC on the basis of a cohort of a large, non-randomised, phase II study showing tumour responses and manageable safety in patients whose disease had progressed after ≥2 prior lines of chemotherapy [16]. In a phase III trial carried out in Asian patients, nivolumab administered as third or later line of treatment improved OS versus placebo, resulting in approval in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea for the treatment of unresectable advanced or recurrent GC progressing after chemotherapy [2].

Avelumab is a human anti-PD-L1 IgG1 monoclonal antibody that is approved for advanced urothelial carcinoma and metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma and has demonstrated efficacy in various solid tumours, including GC/GEJC [17, 18]. In a cohort of the phase I JAVELIN Solid Tumor trial, avelumab administered as first-line maintenance or second-line treatment of patients with advanced GC/GEJC showed durable antitumour activity and an acceptable safety profile [19]. Avelumab has also shown encouraging results in a phase I cohort of Japanese patients with advanced GC/GEJC that progressed after chemotherapy in the JAVELIN Solid Tumor JPN trial [20].

Here, we report the results from a randomised, phase III trial of avelumab versus physician’s choice of chemotherapy as third-line treatment in patients with advanced GC/GEJC.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

JAVELIN Gastric 300 (NCT02625623) is a multicentre, international, randomised, open-label, phase III trial assessing avelumab versus physician’s choice of chemotherapy as a third-line treatment of patients with advanced GC/GEJC. Eligible patients were required to be aged ≥18 years; have histologically confirmed recurrent, unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic GC/GEJC (with either measurable or non-measurable disease) for which they received two prior lines of systemic treatment; and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1. Exclusion criteria included prior treatment with T-cell coregulatory protein inhibitors, concurrent anticancer treatment, and concurrent treatment with immunosuppressive agents (see supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and other regulations. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee of each centre; all patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Treatment

All patients were randomised 1 : 1 to receive BSC and either avelumab 10 mg/kg by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks or physician’s choice of chemotherapy. Premedication with diphenhydramine and acetaminophen was required 30–60 min before avelumab infusion. Permitted options in the chemotherapy arm included paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 4-week treatment cycle or irinotecan 150 mg/m2 on days 1 and 15 of a 4-week treatment cycle. Patients randomised to the chemotherapy arm and deemed ineligible for chemotherapy were allowed to receive BSC without chemotherapy (irrespective, the non-avelumab-containing treatment arm will be referred to as the ‘chemotherapy’ arm hereafter). All patients were treated until progression, death, intolerable toxicity, or any other protocol-defined treatment discontinuation criterion was met.

End points

The primary objective was to demonstrate superiority of avelumab versus chemotherapy in terms of OS. Key secondary objectives included comparing progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response rate (ORR) per independent review committee (IRC) assessment, as well as safety/tolerability. Exploratory objectives included assessing duration of and time to response and evaluating tumour shrinkage of target lesions from baseline, disease control rate (DCR), and tumour cell PD-L1 expression levels in relation to response parameters (DCR, ORR, PFS, and OS).

Assessments

On-treatment decisions were made at the discretion of the investigator (including discontinuation from study treatment), whereas assessments reported here are based on a blinded IRC. PFS and objective response were assessed per RECIST v1.1 by an IRC [21]. Adverse events (AEs) were evaluated using the NCI-CTCAE v4.03 (see supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Statistics

The sample size for this trial was selected to provide 90% power to demonstrate improvement of 2 months of median OS time from 4 to 6 months [the primary end point; equivalent to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.67 at the one-sided 2.5% overall significance level]. The primary analysis of comparing OS between treatment groups used a stratified, one-sided log-rank test on the intention-to-treat population and was planned for when 256 OS events had occurred and follow-up was ≥6 months. The stratification factor of region (Asia versus non-Asia) was used for the stratified statistical analysis of the primary and key secondary end points. Time-to-event end points were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method, and confidence intervals (CIs) for the medians were calculated using the Brookmeyer–Crowley method.

Results

Patients demographics and treatment duration

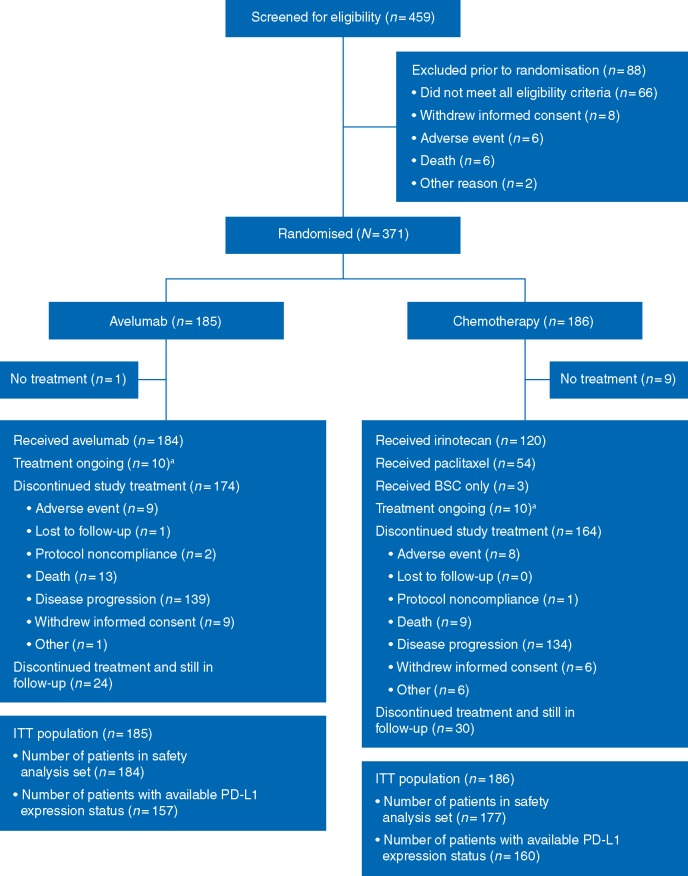

Between 28 December 2015 and 13 March 2017, 459 patients were screened for participation, and 371 were enrolled (Figure 1). Of the 371 enrolled patients, 185 and 186 patients were randomised to the avelumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively. In the chemotherapy arm, 120 (64.5%) patients received irinotecan, 54 (29.0%) paclitaxel, and 3 patients (1.6%) received BSC only. Patient demographics and disease characteristics were generally balanced between arms (Table 1). Notably, 93 patients (25.1%) were enrolled in Asian countries.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. aAs of 14 September 2017. BSC, best supportive care; ITT, intention-to-treat; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1.

Table 1.

Select baseline characteristics in the intention-to-treat population

| Characteristics | Avelumab | Chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 185) | (n = 186) | |

| Age, median (range), years | 59 (29–86) | 61 (18–82) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 140 (75.7) | 127 (68.3) |

| Female | 45 (24.3) | 59 (31.7) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 66 (35.7) | 62 (33.3) |

| 1 | 119 (64.3) | 124 (66.7) |

| Histology | ||

| Tubular | 67 (36.2) | 66 (35.5) |

| Signet ring | 42 (22.7) | 36 (19.4) |

| Mucinous | 15 (8.1) | 21 (11.3) |

| Papillary | 3 (1.6) | 5 (2.7) |

| Other | 57 (31.3) | 58 (31.2) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Tumour site | ||

| Gastric | 122 (65.9) | 138 (74.2) |

| Gastro-oesophageal junction | 63 (34.1) | 48 (25.8) |

| Geographic region | ||

| Europe | 111 (60.0) | 114 (61.3) |

| Asia | 46 (24.9) | 47 (25.3) |

| North America | 14 (7.6) | 11 (5.9) |

| Rest of the world | 14 (7.6) | 14 (7.5) |

| Race | ||

| White | 119 (64.3) | 117 (62.9) |

| Asian | 47 (25.4) | 47 (25.3) |

| Black | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Not collected/missing | 18 (9.7) | 21 (11.4) |

| Time since diagnosis of metastatic disease, median (range), months | 13.6 (2–106) | 13.9 (3–64) |

| Number of prior anticancer therapies for locally advanced/metastatic disease | ||

| 1a | 26 (14.1) | 22 (11.8) |

| 2 | 158 (85.4) | 161 (86.6) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| ≥4 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (1.1) |

| PD-L1 status, ≥1% staining threshold on tumour cells | ||

| Positive | 46 (29.3) | 39 (24.4) |

| Negative | 111 (70.7) | 121 (75.6) |

Data are number of patients (%) unless specified otherwise.

Patients who progressed on neoadjuvant therapy without receiving surgery or adjuvant therapy within 6 months of treatment discontinuation were considered to have received one line of prior treatment of advanced, inoperable disease.

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1.

At data cut-off (14 September 2017), median duration of treatment in the avelumab arm was 8.0 weeks (range 2–66) and patients received a median of 3 doses (range 1–31), while the chemotherapy arm had median treatment duration of 9.0 weeks (range 4–58) and patients received a median of 5 doses (range 1–39). Median duration of follow-up was 10.6 months in both the avelumab (range 0.1–17.8) and chemotherapy (range 0.0–17.6) arms. Twenty patients (5.4%) were still receiving study treatment [10 (5.4%) in each arm] at data cut-off. Disease progression was the most common reason for discontinuation in both the avelumab [n = 139 (75.1%)] and chemotherapy [n = 134 (72.0%)] arms. Post-treatment anticancer drug therapy was received by 58 patients (31.3%) and 66 patients (35.4%) in the avelumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively; the use of post-progression chemotherapy was balanced between arms (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Seventeen patients (9.4%) had detectable antidrug antibodies in the avelumab arm.

Efficacy

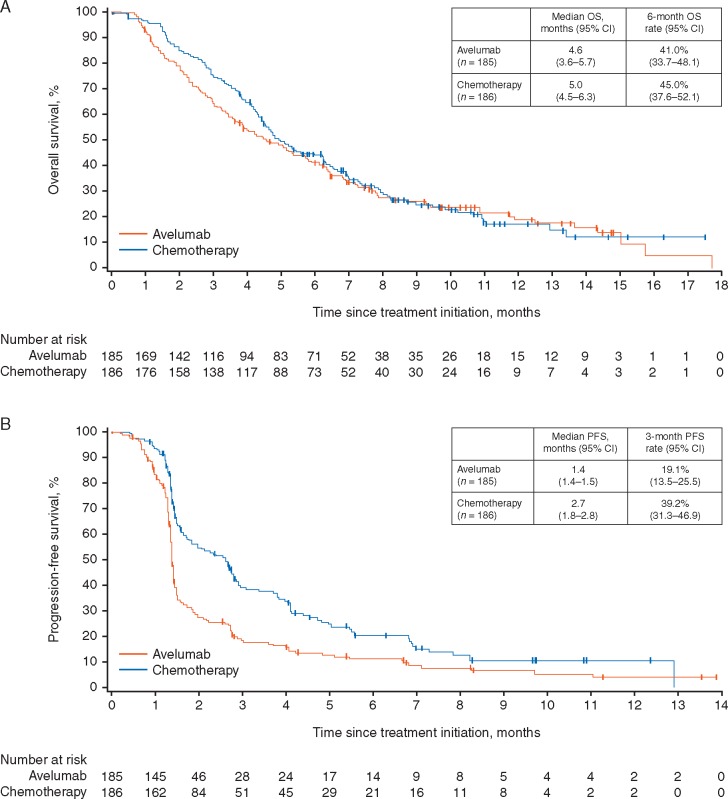

The intention-to-treat population (all patients randomised to study treatment) comprised all 371 randomised patients. Median OS, the primary end point, was 4.6 months (95% CI 3.6–5.7) in the avelumab arm compared with 5.0 months (95% CI 4.5–6.3) in the chemotherapy arm [HR =1.1 (95% CI 0.9–1.4); P = 0.81] (Figure 2). There were no statistically significant differences between the irinotecan and paclitaxel chemotherapy subgroups (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). When assessing solely patients with disease control, median OS favoured avelumab [12.5 months (95% CI 7.8–17.8) versus 8.0 months (95% CI 7.0–11.0)].

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots of median (A) overall survival (OS) and (B) progression-free survival (PFS) in the intention-to-treat population (n = 371).

Median PFS was 1.4 months (95% CI 1.4–1.5) in the avelumab arm and 2.7 months (95% CI 1.8–2.8) in the chemotherapy arm [HR =1.73 (95% CI 1.4–2.2); P > 0.99].

Subgroup analyses of OS according to baseline demographics and disease characteristics, including PD-L1 expression, displayed no significant differences favouring either treatment arm, while PFS subgroup analyses consistently favoured the chemotherapy arm (supplementary Figures S2 and S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The confirmed ORR was 2.2% (n = 4, 95% CI 0.6–5.4) and 4.3% (n = 8, 95% CI 1.9–8.3) in the avelumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively (Table 2). At data cut-off, eight patients had ongoing responses in the avelumab (n = 3) and chemotherapy (n = 5) arms. ORRs by patient subgroup are shown in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. Median time to response was 12.2 weeks (range 5.7–17.6) in the avelumab arm and 11.6 weeks (range 4.3–23.6) in the chemotherapy arm (supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Median duration of response was not determined (range 1.4–5.5) and 5.5 months (range 1.5–7.0) in the avelumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively. The ORR was similar in an exploratory post hoc analysis of only randomised patients with measurable disease at baseline (2.0% versus 4.6% in the avelumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively).

Table 2.

Confirmed response rate per IRC in the intention-to-treat population

| Avelumab | Chemotherapy | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 185 | n = 186 | |

| Best objective response, n (%)a | ||

| CR | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| PR | 3 (1.6) | 7 (3.8) |

| SD | 30 (16.2) | 62 (33.3) |

| Non-CR/non-PD | 7 (3.8) | 12 (6.5) |

| PD | 94 (50.8) | 59 (31.7) |

| Non-evaluableb | 50 (27.0) | 45 (24.2) |

| ORRc (95% CI), %d | 2.2 (0.6–5.4) | 4.3 (1.9–8.3) |

| Disease control rate (95% CI), %e | 22.2 (16.4–28.8) | 44.1 (36.8–51.5) |

Clinical activity of best objective response based on confirmed responses.

Non-evaluable includes ‘missing’ and ‘not assessable’.

Objective response rate is defined as the proportion of patients with best objective response of CR or PR.

95% confidence interval using the Clopper–Pearson method.

Disease control rate is CR+PR+SD (including non-CR/non-PD).

CR, complete response; IRC, independent review committee; ORR, objective response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Safety

The safety analysis set (all patients who were administered any dose of study treatment or BSC only) comprised 184 patients treated with avelumab and 177 patients treated with chemotherapy. Treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) of any grade occurred in 90 patients (48.9%) in the avelumab arm and 131 patients (74.0%) in the chemotherapy arm (Table 3). Grade ≥3 TRAEs occurred in 17 patients (9.2%) in the avelumab arm and 56 patients (31.6%) in the chemotherapy arm.

Table 3.

Incidence of TRAEs (any grade in >10% or grade ≥3 in >1%) in the safety analysis set

| Avelumab (n = 184) |

Chemotherapy (n = 177) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Grade 4/5a | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Grade 4/5b | |

| Any TRAE | 90 (48.9) | 17 (9.2) | 1 (0.5) | 131 (74.0) | 56 (31.6) | 13 (7.3) |

| Nausea | 12 (6.5) | 0 | 0 | 50 (28.2) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Diarrhoea | 11 (6.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 47 (26.6) | 6 (3.4) | 0 |

| Neutropeniac | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 (20.9) | 23 (13.0) | 7 (4.0) |

| Alopecia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 (14.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Anaemia | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 24 (13.6) | 11 (6.2) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (3.3) | 0 | 0 | 24 (13.6) | 4 (2.3) | 0 |

| Infusion-related reactiond | 39 (21.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 5 (2.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Asthenia | 7 (3.8) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 22 (12.4) | 5 (2.8) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 11 (6.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 18 (10.2) | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 8 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 17 (9.6) | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| Decreased WBC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 (7.3) | 7 (4.0) | 3 (1.7) |

| Elevated ALT | 6 (3.3) | 3 (1.6) | 0 | 7 (4.0) | 4 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Elevated AST | 7 (3.8) | 4 (2.2) | 0 | 6 (3.4) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (3.4) | 6 (3.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| Elevated blood alkaline phosphatase | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| Elevated GGT | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.2) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| Elevated lipase | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Sudden death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

Data are number of patients (%).

The safety analysis set comprised all patients who were administered any dose of the study medication or best supportive care only.

All TRAEs with avelumab were grade 4.

All TRAEs with chemotherapy were grade 4, except for 1 event of grade 5 sudden death.

Includes the preferred terms neutropenia and neutrophil count decreased.

Includes adverse events categorised as infusion-related reaction, drug hypersensitivity, or hypersensitivity reaction that occurred on the day of infusion or day after infusion, in addition to signs and symptoms of infusion-related reaction that occurred on the same day of infusion and resolved within 2 days.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; TRAE, treatment-related adverse event; WBC, white blood cell.

TRAEs led to discontinuation in seven patients (3.8%) in the avelumab arm and nine patients (5.1%) in the chemotherapy arm. Death related to treatment occurred in one patient (0.6%; sudden death) in the chemotherapy arm; there were no treatment-related deaths in the avelumab arm. Following comprehensive medical review, 12 patients (6.5%) were found to have an immune-related AE with avelumab, which was grade ≥3 in 4 patients (2.2%; autoimmune hepatitis, autoimmune hypothyroidism, colitis, and elevated AST). Treatment-related infusion-related reactions, as evaluated according to a composite definition of preferred terms including signs and symptoms, occurred in 39 (21.2%) and 5 (2.8%) patients in the avelumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively.

Discussion

The JAVELIN Gastric 300 trial, the first study to compare an anti-PD-L1 antibody (avelumab) to chemotherapy in third-line treatment of GC/GEJC, did not meet its primary end point of improving OS or the secondary end points of PFS and ORR. Avelumab showed clinical activity in patients with GC/GEJC previously treated with two prior regimens for advanced disease, although not superior to chemotherapy; moreover, the safety profile of avelumab was superior to that of chemotherapy.

The first reported phase III trial of a PD-1/PD-L1 agent in advanced GC/GEJC was ATTRACTION-2 (NCT02267343), which used a placebo instead of an active comparator in the control arm. In ATTRACTION-2, nivolumab demonstrated superiority in OS [5.26 versus 4.14 months; HR =0.63 (95% CI 0.51–0.78); P < 0.0001] compared with placebo as third or later line of therapy in Asian patients with advanced GC/GEJC [2]. KEYNOTE-061 (NCT02370498), a randomised, phase III trial comparing pembrolizumab with paclitaxel as second-line treatment in patients with advanced GC/GEJC and disease progression after platinum and fluoropyrimidine doublet therapy, failed to meet its primary end point of OS [9.1 versus 8.3 months; HR =0.82 (95% CI 0.66–1.03); P = 0.042 (one-sided)] in patients with a PD-L1 combined positive score ≥1 [22]. To our knowledge, JAVELIN Gastric 300 and KEYNOTE-061 are the only randomised trials comparing anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies with chemotherapy in patients with previously treated GC/GEJC. Although not approved for use in the third-line setting, chemotherapy is frequently used on the basis of several studies that have suggested improved patient outcomes relative to BSC or placebo [23].

GC/GEJC is biologically heterogeneous, which increases the difficulty of treatment. However, we did not find evidence of clinical benefit compared with commonly used chemotherapy in any of the examined subgroups, including tumour PD-L1 expression status. Furthermore, the impact of PD-L1 expression on prognosis in advanced GC/GEJC is not completely clear. Recent findings from a meta-analysis suggested that PD-L1 expression levels are associated with OS [24]. Conversely, this study and others have not shown a strong link between prognosis and tumour PD-L1 expression in patients with GC/GEJC [13]. Potential differences in patient cohorts, immunohistochemistry methods, and end points may account for these findings.

Another important finding from our study is that fewer patients had TRAEs with avelumab than with chemotherapy (either any-grade or grade ≥3 TRAEs). These results demonstrate that avelumab is better tolerated than chemotherapy in patients with heavily pretreated GC/GEJC, supporting the potential of avelumab for combination or maintenance therapy, even in later stages of disease. Nevertheless, the optimal strategy for incorporating checkpoint inhibitors into the continuum of care for patients with advanced GC/GEJC is still unknown, and studies of alternative anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment strategies in earlier lines of therapy are warranted.

Ongoing randomised, phase III trials for advanced GC/GEJC evaluating checkpoint inhibitors in the first-line setting include CheckMate 649 (NCT02872116), comparing nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus nivolumab plus investigator’s choice of chemotherapy (XELOX or FOLFOX) versus chemotherapy alone. ATTRACTION-4 (NCT02746796) is a phase II/III trial evaluating nivolumab plus chemotherapy (oxaliplatin plus either S-1 or capecitabine) versus chemotherapy alone in Asian patients. KEYNOTE-062 (NCT02494583) is comparing pembrolizumab as monotherapy or in combination with cisplatin/5-FU (or capecitabine) versus cisplatin/5-FU (or capecitabine) alone as treatment of patients with PD-L1+ tumours. JAVELIN Gastric 100 (NCT02625610), a randomised, phase III trial is comparing single-agent avelumab administered after patients receive at least stable disease with 3 months of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy as switch-maintenance treatment versus continuation of chemotherapy.

Results from these randomised, controlled trials will contribute to the unmet need for therapeutic efficacy and safety data to inform standardised guidelines for the management of advanced GC/GEJC and potentially identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from checkpoint inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families, investigators, co-investigators, and study teams at each of the participating centres, at Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, and at EMD Serono, Billerica, MA, USA (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Funding

This work was supported by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, and is part of an alliance between Merck KGaA and Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA. Medical writing support was provided by ClinicalThinking, Inc., Hamilton, NJ, USA, and funded by Merck KGaA, and Pfizer Inc. No grant number is applicable.

Disclosure

Y-JB reports consultancy or advisory role with ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Five Prime Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Green Cross, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Samyang Biopharm; and research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Boston Biomedical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CKD, Curis, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Five Prime Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Green Cross, Hanmi, MacroGenics, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka, Pfizer, Takeda, and Taiho Pharmaceutical. EVC reports research funding from Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Ipsen, Merck, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche, and Servier. K-WL reports consultancy or advisory role with Merck KGaA, and Sanofi/Aventis; and research funding from AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Daiichi Sankyo, Five Prime Therapeutics, Green Cross, MacroGenics, Merck KGaA, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Taiho Pharmaceutical. LW reports consultancy or advisory role with Amgen, Eisai, Halozyme, and Roche; speaker services for Amgen, Roche, and Sanofi; and travel, accommodations, or expenses from Roche and Servier. MS reports personal fees from AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. M-HR reports honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dae Hwa Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, and Ono Pharmaceutical; and consultancy or advisory with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dae Hwa Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, and Ono Pharmaceutical. HCC reports consultancy or advisory role with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Quintiles, and Taiho Pharmaceutical; research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Taiho Pharmaceutical; and speaker services for Eli Lilly, Merck Serono, and Foundation Medicine. S-EA-B reports consultancy or advisory role with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Nordic Pharma, and Roche; speaker services for AIO gGmbH, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Forum für Medizinische Fortbildung, MCI, Nordic Pharma, Promedicis, and Roche; is the CEO/Founder of IKF Klinische Krebsforschung GmbH; and research funding from Celgene, Eli Lilly, Federal Ministry of Education of Research, German Cancer Aid (Krebshilfe), German Research Foundation, Hospira, Medac, Merck, Roche, Sanofi, and Vifor. NB reports honoraria from Chugai Pharma, Eli Lilly, Merck KGaA, Ono Pharmaceutical, Shionogi Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Yakult Honsha, and his institution has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Taiho Pharmaceutical. MHM reports consultancy or advisory fees and speaker services for Amgen, Bayer, Merck & Co, Merck KGaA, and Roche and has received travel expenses from Amgen, Merck KGaA, and Pfizer. JH and HX and are employees of EMD Serono, a company of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. JH reports personal fees from EMD Serono during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. RH is an employee of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt. IC is an employee of EMD Serono and owns stock in Eli Lilly. JT reports honoraria from Amgen, Baxalta, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck KGgA, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, and Servier; consultancy or advisory role with Amgen, Baxalta, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck KGgA, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, and Servier; and travel, accommodations, or expenses from Amgen, Baxalta, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Merck KGgA, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, and Servier. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M. et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975, 2015; https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015.

- 2. Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T. et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 390(10111): 2461–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wagner AD, Syn NL, Moehler M. et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 8: CD004064.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Digklia A, Wagner AD.. Advanced gastric cancer: current treatment landscape and future perspectives. WJG 2016; 22(8): 2403–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W. et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(Suppl 5): v38–v49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Gastric Cancer. V2.2018; https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf (10 May 2018, date last accessed).

- 7. Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A. et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salati M, Di Emidio K, Tarantino V, Cascinu S.. Second-line treatments: moving towards an opportunity to improve survival in advanced gastric cancer? ESMO Open 2017; 2(3): e000206.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tabernero J, Shitara K, Dvorkin M. et al. Overall survival results from a phase III trial of trifluridine/tipiracil versus placebo in patients with metastatic gastric cancer refractory to standard therapies (TAGS). Ann Oncol 2018; 29(Suppl 5): mdy208.001. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver.4). Gastric Cancer 2017; 20(1): 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 513(7517): 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Amatatsu M, Arigami T, Uenosono Y. et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 is a promising blood marker for predicting tumor progression and prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Sci 2018; 109(3): 814–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawazoe A, Kuwata T, Kuboki Y. et al. Clinicopathological features of programmed death ligand 1 expression with tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte, mismatch repair, and Epstein-Barr virus status in a large cohort of gastric cancer patients. Gastric Cancer 2017; 20(3): 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuan J, Zhang J, Zhu Y. et al. Programmed death-ligand-1 expression in advanced gastric cancer detected with RNA in situ hybridization and its clinical significance. Oncotarget 2016; 7(26): 39671–39679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang L, Zhang Q, Ni S. et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression in gastric cancer: correlation with mismatch repair deficiency and HER2-negative status. Cancer Med 2018; 7(6): 2612–2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW. et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase 2 Clinical KEYNOTE-059 Trial. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4(5): e180013.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patel MR, Ellerton J, Infante JR. et al. Avelumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum failure (JAVELIN Solid Tumor): pooled results from two expansion cohorts of an open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19(1): 51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Brohl AS. et al. Two-year efficacy and safety update from JAVELIN Merkel 200 part A: a registrational study of avelumab in metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma progressed on chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(Suppl): abstr 9507. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chung H, Arkenau HT, Lee J. et al. Avelumab (anti-PD-L1) as first-line maintenance (1L mn) or second-line (2L) therapy in patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer (GC/GEJC): updated phase Ib results from the JAVELIN Solid Tumor trial. Oral presentation at American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2018, 14–18 April 2018, Chicago, IL, Abstr CT111.

- 20. Hironaka S, Shitara K, Iwasa S. et al. Avelumab (MSB0010718C; anti-PD-L1) in Japanese patients with advanced gastric cancer: results from a phase 1b trial. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(Suppl 7): mdw521.047. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(2): 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shitara K, Ozguroglu M, Bang YJ. et al. Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously treated, advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (KEYNOTE-061): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10142): 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zheng Y, Zhu XQ, Ren XG.. Third-line chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96(24): e6884.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gu L, Chen M, Guo D. et al. PD-L1 and gastric cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017; 12(8): e0182692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.