Abstract

We documented lessons learned in the initial design and development of the new Harvard doctor of public health (DrPH) degree, an innovative professional public health doctorate designed to provide advanced education in the field of public health. Using data from program documents, personal participation in the development and administration of the degree, and initial students’ results, we present key learnings from this experience and describe the program’s goals and processes. Now entering its fifth year, the new Harvard DrPH program has enrolled about 70 students and graduated its first 2 classes in a program that combines advanced public health study with leadership development and field engagement. Development of this transformational innovation in advanced public health education required creative approaches to competency development and curriculum design, engagement of faculty to become supportive stakeholders, and substantial support for educational administration. Demand for a program of this type is strong. Continuous improvement is ongoing.

Keywords: public health, public health education, public health leadership, schools of public health, workforce

In 2013, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (hereinafter, HSPH) redesigned its doctor of public health (DPH) degree as part of reforms aimed to distinguish between research degrees and professional degrees. Harvard’s new professional doctor of public health degree is the DrPH. It links advanced academic training and professional competency development in ways distinct from many other DrPH programs that provide more emphasis on research training, similar to a doctor of philosophy (PhD) degree. In May 2017, the first 8 students graduated with the new DrPH degree; in May 2018, another 25 students graduated. This article summarizes lessons learned in the design and implementation of this degree during the first 4 years (2013-2017) until the first students graduated. This article does not evaluate learning outcomes of the program, nor does it assess the career impact on those obtaining this degree.

Background

Calls for redesigning graduate professional public health education preceded the launch of the new Harvard DrPH.1 The DrPH degree was originally envisioned by Rosenau2 and by Welch and Rose in 1915.3 In 1966, Roemer4 proposed a multidisciplinary doctoral professional degree, a DrPH degree equivalent to the doctor of medicine, to meet “the need for personnel to plan, organize, and operate health care systems” rather than treat individual patients.4,5 Fineberg et al1 explored this idea further. The Institute of Medicine reviewed public health education in 19886 and again in 2002, noting that “changes are needed in…academic settings and curriculum.”7 A Lancet Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century emphasized how public health education could address the emerging needs of complex health systems by recommending combining competencies related to health and health systems with bringing about change to improve people’s health.8 In 2013, a supplemental issue of the American Journal of Public Health, renewing these concerns, highlighted reforms to programs and curricula in schools of public health.9-14 In addition to these noteworthy contributions, lively exchanges of ideas on goals, content, and competencies for public health professional education have been published in various academic and professional sources since 2000.15-19

By 2013, doctoral degrees in public health had changed little in the United States. Many DrPH programs claimed to educate future public health leaders, but they required a research-focused doctoral dissertation similar to research-focused doctoral degrees, such as the PhD or doctor of science (SD). Research training was a primary focus of the DrPH, with less emphasis on competencies in knowledge translation and transformative leadership. The new Harvard DrPH sought to create a new synthesis that would balance advanced technical knowledge and analytical competencies with training in change competencies, knowledge, and skills to lead and implement improvements in the public’s health. This new synthesis placed more emphasis on research translation competencies than on research production skills in comparison with Harvard’s doctoral-level research degrees, the SD and the PhD.

Concept

Harvard’s new DrPH redesigned the preexisting DPH that was Harvard’s first public health doctoral degree. By 2013, the DPH was one of 3 doctoral degrees available to students at HSPH: a PhD in 3 fields and an SD and a DPH in most departments. All 3 degrees focused on research training. The primary past distinction between the SD and the DPH was that DPH students had a previous master of public health (MPH) degree and health professional background, whereas those receiving the SD typically had neither an MPH degree nor a health professional background. By 2013, however, this distinction had disappeared. Fewer than 10 students were enrolled in the DPH degree, whereas more than 400 were enrolled in the SD and PhD programs.

Redesigning the DPH was part of HSPH’s “Roadmap to 2013” reforms coinciding with the school’s 100th anniversary.20 A clearer framing of the school’s degree offerings into professional and research pathways was proposed. The former would be the MPH and (new) DrPH degrees, and the latter included existing PhDs, SDs, and a new PhD in population health sciences that would replace the SD.

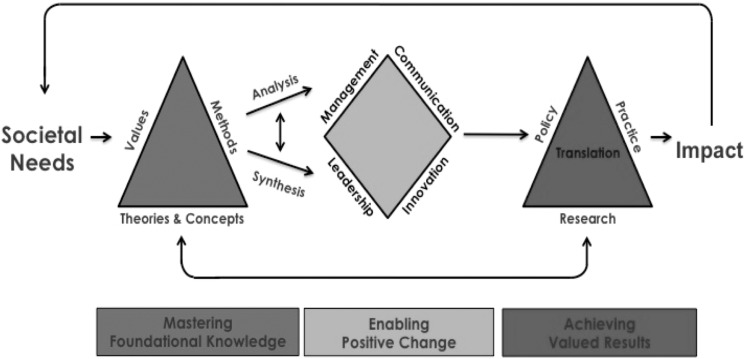

This new Harvard DrPH program linked 3 competency domains.21 One is a foundation in theories and methods, including values in public health and competencies in analysis and synthesis of existing knowledge. A second domain focuses on effecting change as a leader. The third domain emphasizes combining knowledge with change-oriented skills through translating knowledge into results that matter for the public’s health. The strong emphasis on competencies in the second and third domains differentiates the new DrPH from the other doctoral degrees at HSPH (Figure).

Figure.

Conceptual framework developed during planning and used to design the new doctor of public health degree at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2013. Data source: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.23

The dean appointed a transformation team consisting of 15 faculty and staff members, including 5 departments and the dean’s office, with a mix of senior research, leadership, and practice faculty. The transformation team prepared a proposal for the new DrPH. Incorporating reviews by several standing academic committees and the full faculty, it proposed innovations in addition to the curriculum framework. These included the following:

Shifting from a department-based program to a school-wide (cross-departmental) program to encourage interdisciplinary learning

Recruiting students with both US domestic and global health interests to bridge domestic and global work emphasizing that “public health is global health”22

Offering a 3-year doctoral degree, with the first 2 years in full-time residence and the third year devoted to a field-based culminating experience

Designing a culminating experience around a doctoral-level translational result, different from a doctoral dissertation

Accepting students with highly diverse education and employment backgrounds, ranging from previous master’s-level training to having a strong undergraduate degree with substantial previous work experience

Integrating practice competencies and field experiences throughout the program, not only as a practicum or culminating field experience

These innovations were named the DrPH Doctoral Engagement in Leadership and Translation for Action (DELTA) Learning Method. Delta is also the Greek letter signifying change.

Curriculum

These ideas were transformed into a curriculum of courses and activities comprising 3 years of study and practice. Each competency domain required content and needed to be linked. To develop the curriculum, the DrPH team used a defined set of competencies for guidance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Learning competencies for the doctor of public health degree, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Healtha

| Area of Competency | Stated Competencies |

|---|---|

| Core knowledge |

|

| Theories and concepts |

|

| Values |

|

| Methods |

|

| Translation |

|

| Management |

|

| Leadership |

|

| Communications |

|

| Innovation |

|

a Data source: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.23

b Includes historical changes and current patterns of fertility, mortality, causes of death, and the burden of disease, and the development of health and medical interventions and institutions with a global perspective.

cIncludes technical reports, journal articles, and public communications, among other communication strategies.

The first year of residential study (equivalent to almost 3 semesters, July through May) provided most of the foundational knowledge component through required courses. These courses included core public health competencies in biostatistics, epidemiology, and the history of public health ideas. Theory-related competencies were addressed through required courses in economic theory with public health applications, political analysis, and social theory (including perspectives from anthropology, sociology, and social psychology). Additional methods competencies included required courses in econometrics and qualitative research methods, supplemented by 2 advanced methods elective courses. An integrating seminar engaged small teams of students in policy analysis of an important public health problem. Students were also required to demonstrate competencies in financial accounting and financial management via coursework or online programs and complete 2 additional courses in research methods (quantitative or qualitative) from an approved list (Table 2).

Table 2.

Required courses for doctor of public health (DrPH) students at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, class of 2019a

| Year and Semester | Course Number | Course Name |

|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | ||

| Summer | DrPH 201 | Fundamental Concepts of Public Healthb |

| DrPH 202 | Epidemiologyb | |

| DrPH 203 | Biostatisticsb | |

| DrPH 204 | Regression Methodsb | |

| DrPH 240 | Personal Mastery 1c | |

| HPM 260d | Economicsb | |

| Fall | GHP 525 | Econometrics for Health Policyb |

| SBS 506 | History, Politics, and Public Healthb | |

| GHP 210 | Concepts and Methods for Global Health and Population Studiesb | |

| DrPH 241 | Personal Mastery 2c | |

| DrPH 290 | Qualitative Researchb | |

| DrPH 250 | Enabling Teamsc | |

| Winter | Team field immersionc | — |

| Spring | HPM 247 | Political Analysis for Health Policyb or |

| GHP 269 | Political Analysisb | |

| DrPH 280 | Integrating Seminarb | |

| DrPH 251 | Enabling Large-Scale Changec | |

| HPM 252 | Negotiationc | |

| DrPH 222 | Paradigms of Social Theoryb | |

| Year 2 | ||

| Summer | Individual field immersionb | — |

| Fall and spring | Enabling Change workshopsb | — |

| DrPH 290 | DrPH DELTA Doctoral Project Seminar | |

| Open for electives | — | |

Abbreviations: —, not applicable; DELTA, Doctoral Engagement in Leadership and Translation for Action; GHP, Department of Global Health and Population; HPM, Department of Health Policy and Management; SBS, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

a Source: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.23

b Foundational knowledge courses.

c Enabling change courses.

The enabling-change component proved more challenging than other components. The intention was to encompass competencies in 4 dimensions: leadership, management, communication, and innovation. The initial idea was an integrated studio course on enabling change that took place during several semesters. We soon realized that elements of foundational knowledge would also support this component, such as accounting and financial management, strategy, and organizational behavior. A faculty committee, chaired by a senior professor of public health leadership and including faculty with expertise in these various competency areas, defined the overall framework for enabling change. This framework proposed developing competencies in leadership, management, communication, and innovation, with leadership as an integrative concept, across 4 levels: self, teams, organizations, and systems.

The continuum of competencies beginning with the self and leading to enabling change in large systems inspired the required curriculum, which continues to evolve. In the initial years, it included courses in personal mastery (learning about oneself and learning to learn about oneself), enabling teams, enabling large-scale change, organizational behavior, financial management, and innovation, along with demonstrating competency in financial accounting. The program provided professional leadership coaching support to students in the first year, followed by peer support in the second and third years.

The program committed to integrating field-based practice experience throughout the curriculum. In years 1 and 2, this commitment was realized through field immersions. Field immersions provided an opportunity to practice foundational knowledge and enabling-change competencies as these developed during the first year of the program. The DrPH drew inspiration from the Harvard Business School’s FIELD (Field Immersion Experiences for Leadership Development) program, a year-long course that includes a global external placement with partner organizations.24

The first field immersion, in the January winter session of year 1, was a 3-week team-based residential field engagement with sponsoring organizations. The sponsoring organizations included international and domestic organizations, and the program financed student participation. Students prepared in teams in advance, through the interactive “Enabling Teams” course.

The second field immersion, which took place in the summer after year 1, was an 8-week (320-hour) individual practice engagement with an organization identified by the student. Students were responsible financially, although most students found paid opportunities. Students prepared a learning agreement, approved by both the sponsoring organization and the program, leading to a report upon completion.

The culminating experience of the new Harvard DrPH was the DrPH DELTA Doctoral Project. Its goals and content were described in a student handbook.25 The project offered “an opportunity to the DrPH degree candidate to practice and develop their personal leadership skills while engaging in a project that contributes substantively to public health results.”25 Students began the DELTA Doctoral Project after passing a half-day closed-book written qualifying examination covering all required coursework, including both foundational knowledge and enabling-change courses. They identified a project, typically involving a placement with a host organization, and prepared a proposal under the supervision of a committee composed of 3 members—2 of whom had to be Harvard academic appointees, with an HSPH chair, and 1 of whom could be a relevant professional external to Harvard University or another faculty member. Students had to pass an oral qualifying examination administered by the committee on the proposed project before the work began. Students spent 8 months working on the project itself and an additional month and a half completing written deliverables, and then they took a final oral examination to graduate in May of the third year. Students could petition for additional time to undertake supplementary coursework, spend more time on the doctoral project work, or both.

The DELTA Doctoral Project had 3 deliverables. The first was the DrPH DELTA doctoral thesis, a monograph consisting of an analytical platform and a results statement with a recommended length of approximately 100 pages. The thesis was a substantive intellectual product of doctoral caliber but different from a dissertation for a research doctorate. Today, the latter is usually 3 papers deemed publishable in a peer-reviewed academic journal (Box).

Box.

Doctoral thesis titles of students in the doctor of public health program, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, May 2017

Alamro N. “Geographic Disparities in Saudi Mortality: Toward a Policy-Relevant Analysis”

Almodovar Y. “Stewardship and Accountability of the Government Health Insurance Plan’s Spending in Puerto Rico: A Case Study of the Outpatient Prescription Drug Program”

Andrade G. “From Promise to Delivery: Organizing the Government of Peru to Improve Public Health Outcomes”

Dickelson N. “Exploring Emerging Practices to Improve the Health Status of Medicaid Managed Care Populations Through a Social Determinants of Health Approach”

Lapedis J. “The Use of Multi-Stakeholder Coalitions to Integrate Healthcare and Social Services”

Reynoso J. “Cultivating Total Health: Intervening on Food Insecurity via Implementation of the Clinic-to-Community Integration Strategy”

Seidman G. “Achieving Universal Primary Health Care Through Health Systems Strengthening: Lesotho’s National Primary Health Care Reform”

Vigo D. “On Burden: A Study of the Population-Level Health Effects of Mental Illness”

The second product was described as “other deliverables.” These deliverables could include any important translational outputs from a student’s work, for example, media products (print, internet-based, or using other media), policy white papers, or published research articles. Other deliverables demonstrated translational contributions of the student that would not usually be part of a doctoral thesis.

The third DELTA Doctoral Project deliverable was a “personal journey statement,” which describes the students’ personal growth and development through the DrPH program. The DrPH Doctoral Project Manual25 provides further details on content and assessment criteria.

Program Governance and Faculty Roles

HSPH’s graduate degrees either primarily have cross-departmental governance (MPH and now the PhD) or primarily intradepartmental governance (SD and the master of science [SM] degree). With cross-departmental governance, degree requirements, admissions, and operations are overseen by a school-level multidepartmental committee, although concentrations or majors are managed by departments. With intradepartmental governance, these functions are internal to individual departments. All degrees receive oversight from a school-level committee of educational policy and committee of admissions and degrees, with faculty members representing departments.

The new DrPH program is a school-wide program without departmental concentrations. Having a program without departmental concentrations created a new organizational challenge because departments had to define their own roles to support and manage their contributions to the program.

A DrPH steering committee was initially formed with representation from 5 key departments: biostatistics, epidemiology, health policy and management, global health and population, and social and behavioral sciences. The dean and other senior administrators also sat on this committee, which initially met monthly. It reviewed all program processes and key documents, such as an annual student manual, the DELTA Doctoral Project Handbook, and field immersion guidelines. Student representatives were also invited to join this committee in a spirit of co-invention (ie, involving active participation and feedback from students in the continuing process of program development). The DrPH program formed its own admissions committee, which developed a DrPH-specific admissions process with guidance from the steering committee.

The school-wide nature of the new Harvard DrPH program posed challenges for engaging faculty. Departments give priority to the programs in which they play a more direct managing role in curriculum development, admissions, and allocation of faculty advisors. The DrPH program had to reach out to individual department chairs to seek their support and to individual faculty as academic advisors, chairs, and committee members of DELTA Doctoral Project committees. This process required substantial effort from DrPH staff members, but by the end of the third year, about 40 faculty members from 6 departments were participating in DrPH advising and committees.

The new DrPH program planned to limit each class size to 25 students. The first class had 15 students, and subsequent classes were larger. About 70 students were enrolled by the beginning of the 2017-2018 academic year. A dedicated program team that grew to 5 full-time equivalent staff members grew and managed the DrPH program, including a deputy director, a faculty director for enabling change, an administrator, a field immersion lead, and support staff members. Thanks to a generous monetary gift to launch the program, resources were available to recruit initial staff members and provide modest compensation to faculty participating in program oversight and advising.

Lessons Learned

The new Harvard DrPH was like a start-up company—an exciting new enterprise that broke new ground in educational innovation and built new structures and processes. After 4 years of design and implementation and with the first graduates, much had been put in place. The program was fully staffed and had a large and excellent student body, a complete set of administrative processes, a well-developed curriculum, and a proven pathway to graduation. But the development of the DrPH was far from complete. Many changes were introduced along the way and more are sure to come. Following are some of the key lessons learned.

Excellent Students Are Keen to Pursue an Advanced Professional Degree

The DrPH was marketed as different from a research doctorate. About 200 students applied for the program annually for classes of about 25 students. This large pool of applicants enabled the program to be more selective than the MPH and almost as competitive as the new fully funded PhD. Broad demand is there, and the program has been successful in admitting underrepresented minority students (ie, US citizens and permanent residents from defined underrepresented minority groups).

The DrPH Design Introduced Innovations Requiring Sustained Commitment and Leadership at School and Department Levels

Substantial challenges arose in gaining wider school participation because the program was integrated across departments and across global and domestic interests, and the professional degree required new guidelines and standards. The dean’s presence on the steering committee and advocacy with the department chairs helped to mobilize support from various units for a new initiative, which was not any department’s sole responsibility.

The Research-Oriented Faculty Showed Substantial Interest in Supporting Innovative Applied Public Health Work

Research contributions are a high priority at HSPH, and the faculty have many incentives to focus mostly on their own research. Nonetheless, many faculty welcomed the opportunity to teach and advise students whose orientation was toward applied public health work. These faculty contributed substantially to the program through dedicated teaching, advising, and committee work. Professionally oriented DrPH students differ from research doctoral students. Faculty report informally that working with DrPH students strengthens their own engagement in public health action and builds on their research expertise.

DrPH Students Bring New Perspectives

DrPH students arrive with more practical work experience than many master’s or research doctoral students (minimum of 4 years’ full-time equivalent experience for the DrPH), although often with less previous quantitative training. These differences introduce a valuable diversity into the classroom and community and result in products of more direct public health application than research articles. Such applied work may strengthen the school’s reputation for impact in new ways.

Sustainable Financing of the DrPH Will Require Fundraising

The DrPH benefited from an initial gift supporting its launch, followed in year 3 by an additional gift from an anonymous donor. Still, typical students self-finance much of the costs of their degree, which can reach $180 000 during a 3-year period, including tuition and living expenses. DrPH students are concerned about their financial obligations and equity with better-funded research doctoral students in the school. They may finance about half of their total costs through self-generated grants, work, and loans. More fellowship support for DrPH students would sustain the program and create opportunities for students in financial need.

The DELTA Doctoral Project Needs Further Development and Refinement

Creating a culminating experience for a professionally focused Harvard doctorate that was different from the traditional dissertation was an important educational achievement. A question often asked is, “What makes these DrPH requirements a qualification for a doctoral degree?” We reflect back to Milton Roemer’s earlier idea of the DrPH as equivalent to the doctor of medicine degree. We have a century of experience in determining who is qualified for a doctor of medicine degree. The design of the DrPH can contribute to the broader assessment for the doctorate in public health. With the program now producing results, its criteria and standards should be reviewed.

More Work Is Needed to Develop Advanced Competencies in “Enabling Change

HSPH has taught public health leadership and related competencies to master’s students for years.26 Most DrPH students enter the program with a previous master’s degree and can pursue additional courses. Other Harvard schools, such as the Business School and the Kennedy School of Government, have more diverse offerings in these areas. The DrPH program challenges HSPH to enhance its distinct public health leadership curriculum. The DrPH program has a dedicated director for enabling change and continues to develop this innovative didactic element with new courses and applied experiences.

Way Forward

The first graduation of new Harvard DrPH students in May 2017 was a milestone to celebrate, but much work needs to be done, particularly in 6 key areas: (1) securing continued and broader departmental and faculty commitment to the program, (2) strengthening the contributions of the DrPH program to broader education at HSPH, (3) developing a sound financial model for program funding and student support, (4) strengthening the school-based curriculum in leadership and related competencies, (5) strengthening the content and integration of field immersions, and (6) further developing the DrPH DELTA Doctoral Projects. A new faculty director was appointed to lead the program in 2018. Readers are referred to the program website at www.hsph.harvard.edu/drph for the latest information.

Each of the 6 areas benefits from the substantial foundation already in place and presents intellectual, didactic, financial, and operational challenges and opportunities. The Harvard DrPH is making an important contribution to realizing the vision of advanced professional public health education. As Milton Roemer wrote 50 years ago,

The effective performance of health care systems in the United States and throughout the world requires the education of thousands of doctors of public health. I do not mean doctors of medicine with a bit of supplementary training in public health. The need is for specialists in the health of populations, prepared to at least the same level of professional competence as physicians dealing with the sickness of an individual patient.4

Acknowledgments

Many colleagues contributed to the development and implementation of the new Harvard doctor of public health (DrPH) degree. We appreciate the support of Dean Michelle Williams in the development of the program as department chair in epidemiology and member of the steering committee and her continued support as dean of the school. Also, although there are too many people to mention individually, of special note are, in alphabetical order: Jennifer Betancourt, Alexander Hendren, David Hunter, Aria Jin, Howard Koh, Ian Lapp, Kimberlyn Leary, Michael McCormack, Frances Newton, Fawn Phelps, Shaloo Puri, Nancy Turnbull, Gary Williams; members of the DrPH Transformation Team, Steering Committee, and Enabling Change Committee; and DrPH students in the first 3 cohorts of the program. The authors appreciate valuable comments received from reviewers and the journal, which greatly improved the article. Current information on the Harvard DrPH can be found at www.hsph.harvard.edu/drph.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Fineberg HV, Green GM, Ware JH, Anderson BL. Changing public health training needs: professional education and the paradigm of public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:237–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenau MJ. Courses and degrees in public health work. JAMA. 1915;64(10):794–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Welch WH, Rose W. Institute of Hygiene: A Report to the General Education Board of Rockefeller Foundation. New York: Rockefeller Foundation; 1915. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roemer MI. The need for professional doctors of public health. Public Health Rep. 1966;101(1):21–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roemer MI. Preparing public health leaders for the 1990s. Public Health Rep. 1988;103(5):443–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM, eds. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levy M, Gentry D, Klesges LM. Innovations in public health education: promoting professional development and a culture of health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):S44–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fried LP. Innovating for 21st century public health education: a case for seizing this moment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):s5–s7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thibault GE. Public health education reform in the context of health professions education reform. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):s8–s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koh HK. Educating future public health leaders. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):s11–s13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lachance JA, Oxendine JS. Redefining leadership education in graduate public health programs: prioritization, focus, and guiding principles. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):s60–s64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bennett CJ, Watson SL. Improving the use of competencies in public health education. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 5):s65–s67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. Doctor of public health (DrPH) core competency model, version 1.3. November 2009 https://www.aspph.org/teach-research/models/drph-model. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- 16. Calhoun JG, Dollett L, Sinioris ME, et al. Development of an interprofessional competency model for healthcare leadership. J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(6):375–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. Core competencies for public health professionals. June 2014. http://www.phf.org/resourcestools/Documents/Core_Competencies_for_Public_Health_Professionals_2014June.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- 18. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Center for Creative Leadership. Ladder to leadership: developing the next generation of community healthcare leaders. March 2015 https://www.ccl.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/LTLDevelopingHealthcare.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- 19. Wright K, Rowitz L, Merkle A, et al. Competency development in public health leadership. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1202–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frenk J, Hunter DJ, Lapp I. A renewed vision for higher education in public health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):S109–S113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The Harvard DrPH: curriculum. 2018. www.hsph.harvard.edu/drph/curriculum-3 . Accessed November 6, 2017.

- 22. Fried LP, Bentley ME, Buekens P, et al. Global health is public health. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):536–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Harvard DrPH program student manual for students entering July 2016. Updated February 10, 2017 https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1496/2018/07/DrPH-Student-Manual-for-Class-of-2019.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2018.

- 24. Harvard Business School. The field method: bridging the knowing-doing gap. http://www.hbs.edu/mba/academic-experience/Pages/the-field-method.aspx . Accessed August 18, 2018.

- 25. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. DrPH DELTA doctoral project manual, class of 2019. Updated July 2018 https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1496/2018/07/DrPH-Delta-Doctoral-Project-Manual-Cohort-3.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2018.

- 26. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Public health leadership. 2018. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/phl . Accessed September 9, 2018.