Abstract

Background

The immune surveillance reactivator lefitolimod (MGN1703), a DNA-based TLR9 agonist, might foster innate and adaptive immune response and thus improve immune-mediated control of residual cancer disease. The IMPULSE phase II study evaluated the efficacy and safety of lefitolimod as maintenance treatment in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) after objective response to first-line chemotherapy, an indication with a high unmet medical need and stagnant treatment improvement in the last decades.

Patients and methods

103 patients with ES-SCLC and objective tumor response (as per RECIST 1.1) following four cycles of platinum-based first-line induction therapy were randomized to receive either lefitolimod maintenance therapy or local standard of care at a ratio of 3 : 2 until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Results

From 103 patients enrolled, 62 were randomized to lefitolimod, 41 to the control arm. Patient demographics and response patterns to first-line therapy were balanced. Lefitolimod exhibited a favorable safety profile and pharmacodynamic assessment confirmed the mode-of-action showing a clear activation of monocytes and production of interferon-gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10). While in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population no relevant effect of lefitolimod on progression-free and overall survival (OS) could be observed, two predefined patient subgroups indicated promising results, favoring lefitolimod with respect to OS: in patients with a low frequency of activated CD86+ B cells (hazard ratio, HR 0.53, 95% CI: 0.26–1.08; n = 38 of 88 analyzed) and in patients with reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (HR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.20–1.17, n = 25 of 103).

Conclusions

The IMPULSE study showed no relevant effect of lefitolimod on the main efficacy end point OS in the ITT, but (1) the expected pharmacodynamic response to lefitolimod, (2) positive OS efficacy signals in two predefined subgroups and (3) a favorable safety profile. These data support further exploration of lefitolimod in SCLC.

Keywords: SCLC, lefitolimod, TLR9 agonist, immunotherapy

Key Message

Maintenance treatment of ES-SCLC patients with the TLR9 agonist lefitolimod in the IMPULSE study showed a favorable safety profile, immunological effects and positive OS signals in two predefined subgroups, with low counts of activated B cells as possible predictive biomarker for an OS benefit. These data support further exploration of lefitolimod alone or in combination in ES-SCLC.

Introduction

Most patients with small-cell lung cancer are diagnosed with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC). Platinum-based combination chemotherapy provides response in at least two-thirds of patients and improves median survival from 3 to 10 months, approximately. On progression, second-line therapy yields response rates of 20%–30%, with median survival times of 6–8 months [1]. Based on the outcome of research over the last decades, SCLC has been referred to as ‘a graveyard for drug development’ and most patients succumb to the disease within 2 years [2]. Thus, the development of treatment options to delay cancer progression and to prolong survival after initial therapy is an unmet need.

In the past it has been shown that VEGFR-inhibition with sunitinib may have impact in this clinical setting [3]. In the rapidly moving field of immuno-oncology, phase III trials assess immune checkpoint inhibition with consecutive maintenance within first-line chemotherapy. These strategies are based on the rationale that chemotherapy not only leads to initial rapid tumor shrinkage with a limited period of disease stability, but also to release of tumor-associated antigens (TAA) as ideal immune targets. The subsequent application of checkpoint-inhibiting antibodies blocks the pathways causing downregulation of the immune response against TAA. ES-SCLC with its high initial response rates to standard platinum-based chemotherapy, a resulting decrease of tumor burden and associated release of TAA could be an ideal setting for such immunotherapeutic strategies [4, 5]. Nevertheless, addition of ipilimumab to chemotherapy did not prolong overall survival (OS) versus chemotherapy alone in patients with newly diagnosed ES-SCLC [6].

However, an efficacious adaptive immune response requires processing and presentation of TAA by dendritic cells as well as allocation of the appropriate cytokine and chemokine environment through cells of the innate immune system. All such immunological requirements for immune surveillance reactivation are fulfilled by the mode-of-action of lefitolimod (MGN1703). Therefore, it was considered as particularly promising for maintenance therapy in ES-SCLC.

Lefitolimod, a TLR9 agonist, comprises covalently closed DNA molecules without chemical or other non-natural modifications, which is crucial for its favorable safety and tolerability features [7, 8]. Lefitolimod targets TLR9-positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and triggers their secretion of IFN-alpha to activate the effector cells of innate immunity (e.g. monocytes) subsequently leading to high systemic levels of IFN-gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10/CXCL10) [9], a chemotactic and angiostatic protein [10]. IFN-alpha results also in activation of myeloid dendritic cells (mDC) for efficacious presentation of TAA to CD4+ but more importantly for cross-presentation of TAA to CD8+ T cells [11]. In previous phases I and II studies lefitolimod showed a favorable safety profile, activation of antitumor immunity and early signs of immunotherapeutic efficacy [7, 12, 13].

Here we report on a randomized phase II trial assessing the efficacy and safety of lefitolimod as a maintenance strategy in ES-SCLC showing objective tumor response after platinum-based combination chemotherapy.

Patients and methods

Detailed descriptions are available in supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Patients

Patients with ES-SCLC and objective tumor response to four cycles of platinum-based first-line therapy with a platinum-based chemotherapeutic regimen were included.

Study design

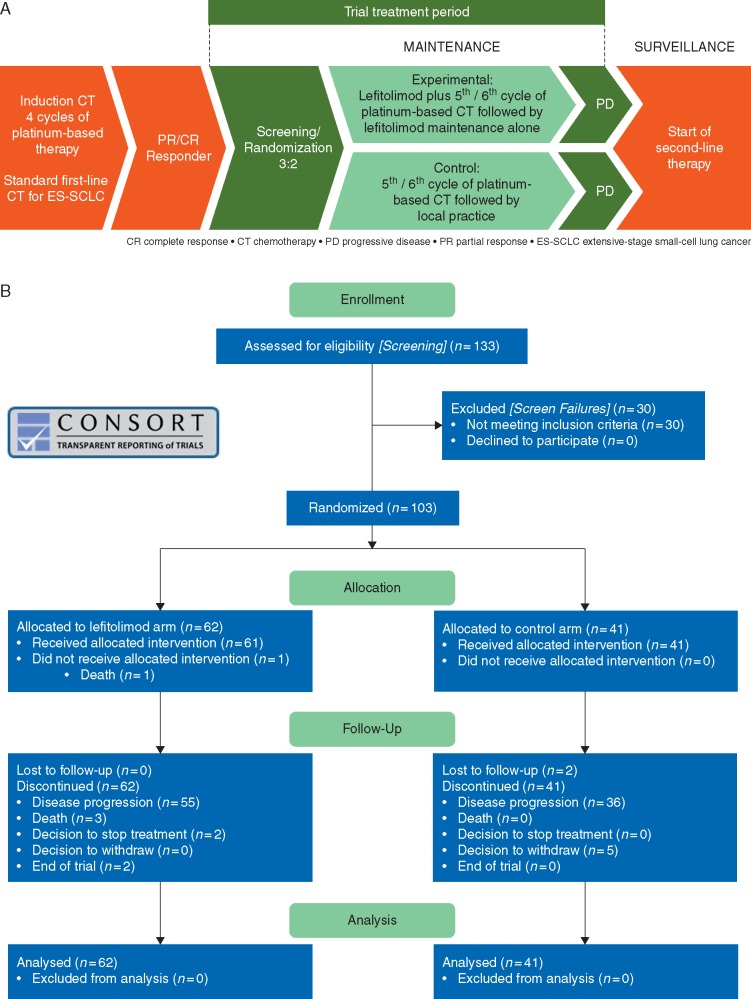

IMPULSE (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02200081) is a randomized, international, multicenter, open-label exploratory phase II trial for OS signal generation. ES-SCLC patients were randomized 3 : 2 to receive lefitolimod maintenance therapy (twice-weekly, 60 mg s.c.) or local standard of care until progression or unacceptable toxicity (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Design of IMPULSE study and CONSORT report chart. (A) Schematic flow chart of IMPULSE, a randomized, controlled, two-arm, multinational phase II clinical trial. (B) CONSORT chart of patient distribution.

Outcome measures

The main efficacy end point was OS in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population. Secondary outcome measures included safety, objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), preplanned subgroup analyses and immunological assessments.

Results

Patient characteristics

From a total of 133 patients screened, 103 patients were enrolled with 62 patients randomized to the lefitolimod and 41 to the control arm by 41 centers in Belgium, Austria, Germany and Spain (Figure 1B). In general, there was a balanced distribution between the two treatment arms regarding demographic factors such as age, sex, race, smoking status, reported COPD and brain metastasis (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). However, some imbalance in the ECOG performance status in favor of the control arm was noted with 30.6% of patients in the lefitolimod arm versus 46.3% of patients in the control group exhibiting ECOG 0. On top of ECOG, there was an imbalance in prophylactic irradiation during the treatment phase with 16.4% in the treatment and 43.6% in the control arm, respectively (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

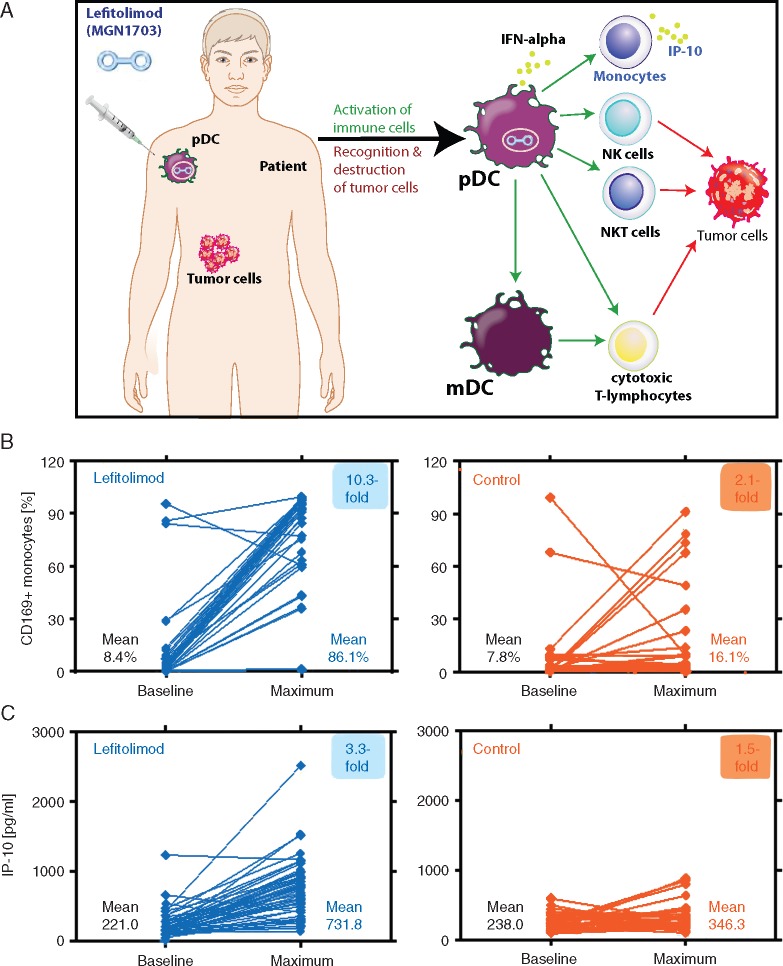

Confirmation of lefitolimod’s mode-of-action

Lefitolimod broadly activates the immune system by targeting predominately TLR9-positive pDC (Figure 2A). This mode-of-action was confirmed in the lefitolimod-treated patients with a clear activation of peripheral monocytes shown by an upregulation of CD169 and elevated IP-10 serum levels in response to subcutaneous lefitolimod treatment (Figure 2B and C), whereas only minor changes occurred in the control patients.

Figure 2.

Immunological analysis of paired patient samples based on lefitolimod’s mode-of-action. (A) Injection of lefitolimod triggers immune surveillance reactivation and antitumor responses. (B) Analysis of activated CD169+ monocytes via flow cytometry of peripheral blood. Paired samples: lefitolimod n = 54 (P < 0.0001), control n = 32 (P = 0.14). (C) Analysis of serum level of chemokine IP-10 via multiplex assay. Paired samples: lefitolimod n = 59 (P < 0.0001), control n = 32 (P = 0.02).

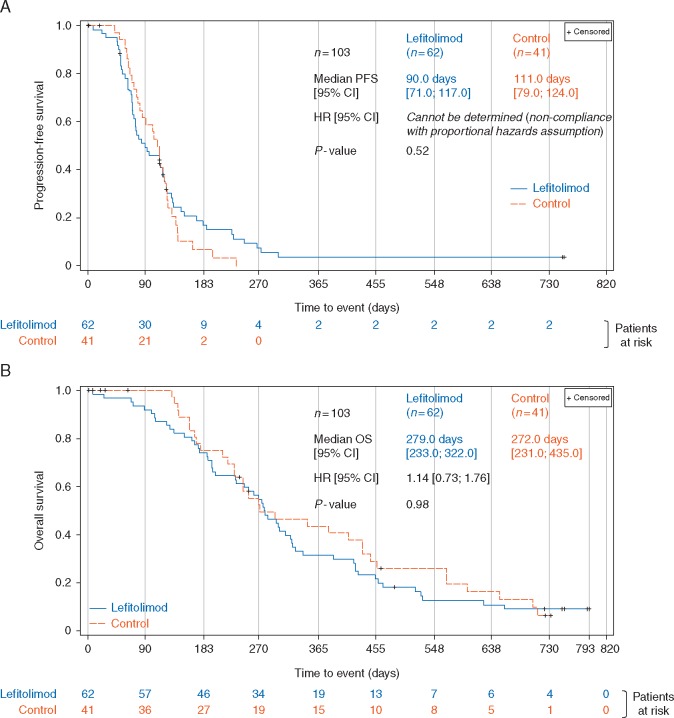

Objective response rate and progression-free survival

There was a trend toward a higher ORR in the lefitolimod arm (11.9%) versus the control arm (8.1%) with an odds ratio of 1.57 (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The PFS within the ITT showed no significant difference (Figure 3A). However, a group of lefitolimod patients exhibited a slower progression with two of them reaching long-term disease control beyond study end (720 days) (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 3.

Progression-free and overall survival of the ITT study population. Kaplan–Meier plot of the PFS (A) and OS (B). Stratified hazard ratio and log-rank P-values are shown.

OS in the ITT population

Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed no relevant difference between the study arms with a median OS of 279 days for the lefitolimod and 274 days for the control group, respectively, and a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.14 (95% CI: 0.73–1.76) comparing 62 lefitolimod with 41 control patients (Figure 3B).

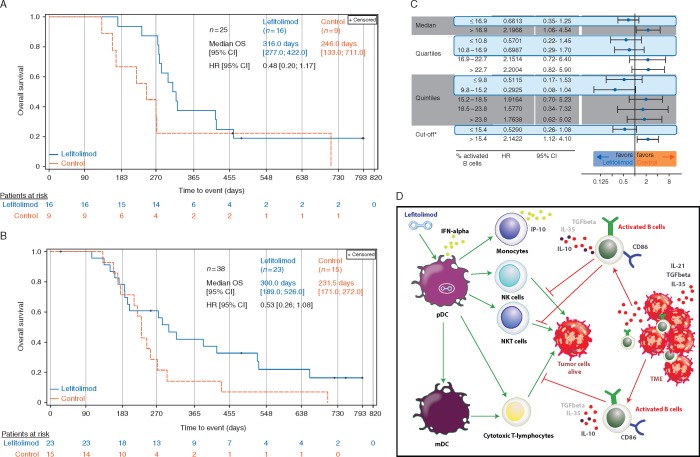

OS in two predefined subgroups

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a frequent underlying disease in SCLC [14]. An OS signal was observed in patients with reported COPD at baseline with a median OS of 316 versus 246 days in the lefitolimod and control group, respectively, and an HR of 0.48 (95% CI: 0.20–1.17) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Overall survival of two subpopulations. (A) Patients with reported COPD at baseline shown in Kaplan–Meier plot. (B) Patients with low number of activated B cells at baseline as depicted in a Kaplan–Meier plot. Central flow cytometric assessment of CD86+CD19+ B cells for cutoff determination at baseline. B cell data were available for 88 of 102 patients. Cutoff defined as 15.4% activated B cells with 38 of 88 patients (43.2%) below cutoff. (C) Robustness of the OS signal in patients with low count of activated B cells: the use of different analysis to confirm the delineated cutoff of 15.4%: median, quartiles and quintiles. (D) Postulated mode-of-action of the activated (regulatory) B cell fraction impairing the lefitolimod-triggered antitumor response. Lefitolimod targets TLR9-positive pDC leading to their activation and production of IFN-alpha initiating subsequent activation of crucial immune cells like NK, NKT and T cells. Activated, regulatory B cells suppress the antitumor properties of these cells via various processes (e.g. secretion of IL-10).

To gain more understanding in the immunological mode-of-action we divided patients at baseline in two groups based on the frequency of CD86+ B cells previously described as activated B cells [15]. In fact, in the predefined subgroup of patients with a low number of activated B cells using a cutoff of 15.4% an OS signal could be detected with a median OS of 300 versus 232 days and an HR of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.26–1.08) (Figure 4B). The robustness of this signal was confirmed using different cutoffs like median, quartiles and quintiles for which a consistent benefit of patients with a low number of B cells was detected (Figure 4C).

Post hoc analysis

Patients benefitting from immunotherapy are typically found in a minor subgroup. Here, we distributed the patients into subgroups of short-, medium- and long-lasting responders (PFS ≤80 days, 81–149 days and ≥150 days, respectively) with mainly radiologic progression as events for PFS determination. A clear association of prolonged PFS with an advantage in OS was detected in lefitolimod patients (HR 0.23, 95% CI: 0.10–0.53 for long-lasting versus short-lasting responders). This does not hold true for control patients (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Another post hoc analysis revealed that strong lefitolimod-induced immune activation—represented as increase of IP-10 or CD169+ monocytes—translated into an OS benefit with HR of 0.66 (95% CI: 0.38–1.15) or 0.50 (95% CI: 0.28–0.90), respectively, when analyzed after 4 weeks of treatment (supplementary Figures S3 and S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Safety profile

Lefitolimod showed a favorable safety profile in this vulnerable population. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) are presented in supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online. One SUSAR of grade 2 leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with platinum-based chemotherapy was reported. Patients received twice-weekly subcutaneous injections of lefitolimod for up to 2 years. High treatment adherence was established with 2031 of 2143 (94.8%) planned doses administered. Only four patients had temporary treatment interruptions due to AE not recurring under resumption of treatment. No patient discontinued or had a dose reduction due to an AE.

Discussion

For the last 30 years, there was no important therapeutic advance in ES-SCLC leading this indication to be designated a recalcitrant cancer [5]. While also the IMPULSE trial in ES-SCLC indicated no improvement of OS in the ITT population, encouraging OS signals were detected in two predefined patient subgroups: (i) Patients with a reported history of COPD and (ii) patients with a low number of activated B cells.

COPD is known as independent risk factor for SCLC [14]. A recent publication indicates an importance of circulating immune-cell alterations in the pathophysiology of COPD [16]. Indeed, we observed an OS signal in lefitolimod patients with reported COPD at baseline. Interestingly, the initial immune cell infiltration in COPD creates a tumor-suppressive environment. However, during persistent COPD chronic inflammation evolves which may in turn facilitate tumor growth [17]. It may be speculated that the imbalanced immune environment in COPD is favorably influenced by lefitolimod-induced immune activation. Unfortunately, for this relatively small subgroup of patients with reported COPD (25/103), no detailed information about the immune status was available precluding further meaningful analysis of immune markers.

For 88 patients, we were able to measure the frequency of activated CD86+ B cells at baseline. The cutoff separating patients with low or high proportions of activated B cells placed 38 patients (43%) into the group with <15.4% of activated B cells. Here, lefitolimod maintenance exerted a noteworthy effect on OS. Activated B cells as characterized here include a population of B cells with regulatory function (Breg). Differentiation of immune cell precursors into Breg is initiated by cytokines secreted by tumor cells and active Breg suppress antitumor responses through inhibition of cytotoxic T cells, NK cells and M1-polarized macrophages [18–20]. Hence, the presence of a high number of Breg, reflected by a high proportion of activated B cells, likely inhibits the antitumor effects driven by lefitolimod (Figure 4D). Thus, a low proportion of activated B cells may be developed as a predictive biomarker for the identification of patients benefiting from maintenance treatment with lefitolimod.

While no relevant PFS benefit for the treatment arm was shown a group of lefitolimod patients exhibited slower progression with two patients reaching long-term disease control (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). In keeping with this, a trend toward a higher ORR in the lefitolimod arm was observed. In a post hoc analysis, patients with short-, medium- and long-lasting responses were analyzed for OS and a strong direct association between PFS and OS benefit is evident in lefitolimod but not in control patients (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). While in ES-SCLC only weak to moderate associations between PFS and OS were observed with standard treatments [21, 22], strong direct PFS to OS associations are a common feature of other immunotherapies. They herein identify a group of patients benefitting from immunotherapy with lefitolimod as well.

Corroborating the mode-of-action of lefitolimod, this study showed a strong and significant increase of CD169+ monocytes as well as of IP-10 within the lefitolimod-treated population. Furthermore, lefitolimod-induced immune activation translated into beneficial OS effects (supplementary Figure S3 and S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Hence, these biomarkers may have the potential for monitoring and guiding lefitolimod treatment.

The favorable safety profile of lefitolimod, described in previous reports [12, 13], was largely confirmed in the current trial. Headache, nausea, asthenia and fatigue are consistent with the mode-of-action expressed by flu-like symptoms in a population recovering from chemotherapy. It can be speculated that cough may also be supported by the mode-of-action in lung cancer patients.

Few drugs undergo evaluation or have recently been investigated in maintenance treatment after first-line chemotherapy in (ES-)SCLC. One is sunitinib, for which a significant PFS improvement did not translate to improved OS [3]. Earlier temsirolimus (CCI 779), given at 25 or 250 mg weekly in maintenance, seemed not to increase PFS in ES-SCLC [23]. Topotecan following cisplatin and etoposide improved PFS but failed to improve OS in ES-SCLC [24].

Another drug currently evaluated in maintenance in an ongoing phase III trial is the antibody-drug-conjugate rovalpituzumab tesirine (Rova-T), which targets Delta-like protein 3 (DLL3), a ligand of the Notch1 receptor [25]. In a phase I expansion cohort of advanced treatment lines of ES-SCLC Rova-T showed promising results with respect to response rate and disease control rate [26]. Therefore, the Rova-T is currently evaluated in a randomized phase III trial, with high DLL3 expression as a predictive biomarker. However, preliminary results from a phase II trial in third-line patients with relapsed or refractory DLL3-expressing SCLC look less promising [27].

Since results from phase I or phase II trials seemed promising [2, 4], treatment options with checkpoint inhibition are quickly expanded into phase III trials, even combinations in conjunction with chemotherapy, allowing for extension into maintenance treatment. A phase I trial of the anti-PD-1-antibody pembrolizumab in ES-SCLC patients resulted in an ORR of 33% [28]. Notably, an OS of 9.2 months reported for pembrolizumab in maintenance after 4–6 cycles of chemotherapy was in a similar range as observed in the IMPULSE study [29].

Due to the blinded IMPULSE study design, the early withdrawal of consent by four control patients could not be compensated and—together with imbalances in ECOG and prophylactic irradiation during treatment which seem to favor the control arm in the population studied—limits the explanatory power of this arm as result of the small sample size.

In summary, the IMPULSE study yielded evidence that treatment with lefitolimod is feasible and safe in ES-SCLC and that especially low counts of activated B cells may be useful as a predictive biomarker for a beneficial OS effect. Keeping in mind that this indication is regarded as a ‘recalcitrant cancer’ [5] and a ‘graveyard for drug development’ [2], with the data presented here there is a clear rationale for further exploration of lefitolimod alone or in combination with other immune-oncological approaches in ES-SCLC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participating patients and their families. We thank all involved investigators and the site staff from the IMPULSE study team.

The IMPULSE study team includes: Dr Georg Pall, Medizinische Universitaet Innsbruck, Univ.-Klinik für Innere Medizin V, Internistische Onkologie, Innsbruck, Austria; Dr Veerle Surmont, Universitair Ziekenhuis Gent, Thoracale Oncologie, Gent, Belgium; Dr Léon Bosquee, Clinique André Renard, Herstal, Belgium; Prof. Paul Germonpré, AZ Maria Middelares, Gent, Belgium; Prof. Dr Wolfgang Brückl, Klinikum Nuernberg Nord, Pneumologie, Med. Klinik 3, Nuernberg, Germany; Dr Christina Grah, Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Havelhoehe, Lungenkrebszentrum—Innere Medizin—Pneumologie, Berlin, Germany; Dr Christian Herzmann, Forschungszentrum Borstel, Klinisches Studienzentrum, Borstel, Germany; Dr Rumo Leistner, Sozialstiftung Bamberg, Zentrum Innere Medizin, Medizinische Klinik IV, Pneumologie, Pneumologische Onkologie, Allergologie und Schlafmedizin, Bamberg, Germany; PD Dr Andreas Meyer, Kliniken Maria Hilf, Klinik für Pneumologie, Mönchengladbach, Germany; Dr Lothar Müller, Onkologische Schwerpunktpraxis Leer-Emden, Praxis Leer, Leer, Germany; Dr Oliver Schmalz, HELIOS Klinikum Wuppertal, Abteilung Onkologie und Palliativmedizin, Medizinische Klinik I Bergisches Tumorzentrum, Wuppertal, Germany; Dr Christian Scholz, Vivantes Krankenhaus Am Urban, Abteilung für Innere Medizin—Hämatologie und Onkologie, Berlin, Germany; Dr Michael Schröder, HELIOS St. Johannes Klinik Duisburg, Institut für spezielle Pharmakotherapie, Klinik für Hämatologie, Onkologie und klinische Immunologie, Duisburg, Germany; Dr Monika Serke, Lungenklinik Hemer, Hemer, Germany; Dr Claas Wesseler, ASKLEPIOS Klinik Harburg, Thoraxzentrum Hamburg, Onkologischer Schwerpunkt, DRG, Hamburg, Germany; Prof. Christian Brandts, Universitaetsklinikum Frankfurt, Med. Klinik II, Frankfurt a. M., Germany; Prof. Hans-Georg Kopp, Medizinische Universitaetsklinik Tuebingen, Medizinische Klinik II, Abt. Internistische Onkologie, Tuebingen, Germany; Dr Wolfgang Blau, Justus-Liebig-Universität, Medizinische Klinik IV, Universitätsklinik, Gießen, Germany; Prof. Frank Griesinger, Klinikzentrum für Strahlentherapie, Hämatologie und Onkologie, Klinik für Hämatologie und Onkologie, Universitätsklinik für Innere Medizin-Onkologie, Oldenburg, Germany; Dr Maria Rosario Garcia Campelo, Hospital Teresa Herrera/CHUAC, A Coruña, Spain; Dr Yolanda Garcia Garcia, Hospital Universitario Parc Tauli, Edificio Santa Fe, Sabadell, Spain; Dr José Manuel Trigo Perez, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Malaga, Spain.

Funding

This trial was sponsored by MOLOGEN AG (no grant number applies).

Disclosure

MT, RMH, MW were investigators and had also advisory roles in this study. MT is advisor/speaker for Roche, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Celgene, AbbVie, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Lilly outside of this work. CM is a consultant to MOLOGEN AG. BW is an advisor to MOLOGEN AG. MS, EW and KK are employees of MOLOGEN AG. All remaining authors have declared no competing conflicts of interest to the presented work.

Contributor Information

IMPULSE study team:

Dr Georg Pall, Dr Veerle Surmont, Dr Léon Bosquee, Prof. Paul Germonpré, Prof. Dr Wolfgang Brückl, Dr Christina Grah, Dr Christian Herzmann, Dr Rumo Leistner, PD Dr Andreas Meyer, Dr Lothar Müller, Dr Oliver Schmalz, Dr Christian Scholz, Dr Michael Schröder, Dr Monika Serke, Dr Claas Wesseler, Prof. Christian Brandts, Prof. Hans-Georg Kopp, Dr Wolfgang Blau, Prof. Frank Griesinger, Dr Maria Rosario Garcia Campelo, Dr Yolanda Garcia Garcia, and Dr José Manuel Trigo Perez

References

- 1. Leighl NB. Sunitinib: the next advance in small-cell lung cancer? J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(15): 1637–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oronsky B, Reid TR, Oronsky A. et al. What’s new in SCLC? A review. Neoplasia 2017; 19(10): 842–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ready NE, Pang HH, Gu L. et al. Chemotherapy with or without maintenance sunitinib for untreated extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study—CALGB 30504. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(15): 1660–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Horn L, Reck M, Spigel DR.. The future of immunotherapy in the treatment of small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 2016; 21(8): 910–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD. et al. Small-cell lung cancer: what do we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2017; 7: 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reck M, Luft A, Szczesna A. et al. Phase III randomized trial of ipilimumab plus etoposide and platinum versus placebo plus etoposide and platinum in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(31): 3740–3748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wittig B, Schmidt M, Scheithauer W. et al. MGN1703, an immunomodulator and toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9) agonist: from bench to bedside. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015; 94(1): 31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmidt M, Hagner N, Marco A. et al. Design and structural requirements of the potent and safe TLR-9 agonistic immunomodulator MGN1703. Nucleic Acid Ther 2015; 25(3): 130–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kapp K, Kleuss C, Schroff M. et al. Genuine immunomodulation with dSLIM. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2014; 3: e170.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nagarsheth N, Wicha MS, Zou W.. Chemokines in the cancer microenvironment and their relevance in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2017; 17(9): 559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corrales L, Matson V, Flood B. et al. Innate immune signaling and regulation in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res 2017; 27(1): 96–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmoll HJ, Wittig B, Arnold D. et al. Maintenance treatment with the immunomodulator MGN1703, a Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonist, in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma and disease control after chemotherapy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014; 140(9): 1615–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weihrauch MR, Richly H, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS. et al. Phase I clinical study of the toll-like receptor 9 agonist MGN1703 in patients with metastatic solid tumours. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51(2): 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang R, Wei Y, Hung RJ. et al. Associated links among smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and small cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis in the International Lung Cancer Consortium. EBioMedicine 2015; 2: 1677–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Janeway CA, Bottomly K.. Signals and signs for lymphocyte responses. Cell 1994; 76(2): 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halper-Stromberg E, Yun JH, Parker MM. et al. Systemic markers of adaptive and innate immunity are associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and spirometric disease progression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018; 58(4): 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGarry Houghton A. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13(4): 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Candando KM, Lykken JM, Tedder TF.. B10 regulation of health and disease. Immunol Rev 2014; 259(1): 259–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Y, Gallastegui N, Rosenblatt JD.. Regulatory B cells in anti-tumor immunity. Int Immunol 2015; 27(10): 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mauri C, Menon M.. Human regulatory B cells in health and disease: therapeutic potential. J Clin Invest 2017; 127(3): 772–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foster NR, Renfro LA, Schild SE. et al. Multitrial evaluation of progression-free survival as a surrogate end point for overall survival in first-line extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Thoracic Oncol 2015; 10(7): 1099–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Imai H, Kaira K, Minato K.. Clinical significance of post-progression survival in lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2017; 8(5): 379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pandya KJ, Dahlberg S, Hidalgo M. et al. A. randomized, phase II trial of two dose levels of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer who have responding or stable disease after induction chemotherapy: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (E1500). J Thor Oncol 2007; 2(11): 1036–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schiller JH, Adak S, Cella D. et al. Topotecan versus observation after cisplatin plus etoposide in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: E7593—a phase III trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19(8): 2114–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saunders LR, Bankovich AJ, Anderson WC. et al. A DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate eradicates high-grade pulmonary neuroendocrine tumor-initiating cells in vivo. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7: 302ra136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rudin C, Pietanza MC, Bauer TM. et al. Rovalpituzumab tesirine, a DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: a first-in-human, first-in-class, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(1): 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. AbbVie Pressroom. AbbVie announces results from phase 2 study evaluating rovalpituzumab tesirine (Rova-T) for third line treatment of patients with DLL-3-expressing relapsed/refractory small cell lung cancer. 2018.

- 28. Ott PA, Elez E, Hiret S. et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(34): 3823–3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gadgeel SM, Ventimiglia J, Kalemkerian GP. et al. Phase II study of maintenance pembrolizumab (pembro) in extensive stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) patients (pts). J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: abstr8504. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.