Abstract

A clinical pharmacokinetic study was performed in 12 healthy women to evaluate systemic exposure to aluminum following topical application of a representative antiperspirant formulation under real‐life use conditions. A simple roll‐on formulation containing an extremely rare isotope of aluminum (26Al) chlorohydrate (ACH) was prepared to commercial specifications. A 26Al radio‐microtracer was used to distinguish dosed aluminum from natural background, using accelerated mass spectroscopy. The 26Al citrate was administered intravenously (i.v.) to estimate fraction absorbed (Fabs) following topical delivery. In blood samples after i.v. administration, 26Al was readily detected (mean area under the curve (AUC) = 1,273 ± 466 hours×fg/mL). Conversely, all blood samples following topical application were below the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ; 0.12 fg/mL), except two samples (0.13 and 0.14 fg/mL); a maximal AUC was based on LLOQs. The aluminum was above the LLOQ (61 ag/mL) in 31% of urine samples. From the urinary excretion data, a conservative estimated range for dermal Fabs of 0.002–0.06% was calculated, with a mean estimate of 0.0094%.

Study Highlights.

What is the current knowledge on the topic?

Limited data exist on human skin absorption of aluminum in vitro and in vivo following topical application.

what question did this study address?

What is the fraction absorbed of aluminum following topical application of ACH‐containing antiperspirants in humans for use in risk assessment?

What does this study add to our knowledge?

This study adds to the experience of using a state‐of‐the‐art analytical technique, optimized accelerated mass spectroscopy, using the rare radioisotope 26Al. The data obtained provide evidence for very low systemic absorption of aluminum following topical application and a quantitative estimate of Fabs of aluminum from antiperspirants for use in risk assessment.

How might this change clinical pharmacology or translational science?

These data can inform and improve the risk assessment for aluminum in antiperspirants. The study provides further experience of using AMS approaches for clinical samples (blood and urine) analysis using a radiotracer approach.

Aluminum is a commonly occurring metal in the earth's crust and, therefore, naturally occurring in water and agricultural products. Humans are exposed to aluminum through food, drinking water, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetic products. Aluminum salts, such as aluminum chlorohydrate (ACH), are widely used as antiperspirants and as treatment for hyperhidrosis.1 A quantitative dermal safety assessment for aluminum in antiperspirants requires a measure of human absorption to relate to the “no observed effect” level (30 mg/kg/day) from the pivotal neurodevelopmental study in rats.2 This toxicological point of departure was used by the Joint Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO)/World Health Organisation (WHO) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) to establish a tolerable weekly intake for aluminum of 2 mg/kg bw/week and by the European Food Standards Agency (EFSA, 2008) who chose a tolerable weekly intake of 1 mg/kg bw/week. Regulatory review by the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS, 2014) and EFSA (2008) in Europe of available data, where putative roles for aluminum have been investigated in cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease/dementia, resulted in the opinion that the evidence is not conclusive in either regard. Leading cancer research institutes worldwide cannot conclude that there is a definitive connection between aluminum and breast cancer. This leads to developmental toxicity being the effect of concern for a risk assessment.

In 2014, the SCCS published an Opinion3 for aluminum in cosmetic products. Although there were human skin absorption studies available on aluminum compounds, the SCCS concluded that the existing data were limited and a data gap was identified. They stated: “The SCCS is of the opinion that due to the lack of adequate data on dermal penetration to estimate the internal dose of aluminum following cosmetic uses, risk assessment cannot be performed. Therefore, internal exposure to aluminum after skin application should be determined using a human exposure study under use conditions.”

In order to determine the internal exposure to aluminum specifically from dermal exposure of ACH‐containing antiperspirants, it is essential to distinguish the antiperspirant‐derived aluminum from all other sources of aluminum. Thus, a state‐of‐the‐art approach was used to monitor the fate of aluminum in humans after topical application. The approach (building on previous studies4, 5) combined the use of 26Al with the highly sensitive technique of accelerated mass spectroscopy (AMS) and an optimized clinical study design.

Aluminum occurs naturally as 26Al and 27Al; however, 26Al is an extremely rare isotope on earth and its natural abundance is only at trace amounts with 27Al dominating at virtually 100% abundance. The 26Al has a long physical half‐life (7.2 × 105 years) and this property enables 26Al to be used as a radioactive microtracer in the highly sensitive technique of AMS analysis of biological samples. Specifically, for the purpose of this study, 7 μg of 26Aluminum hydrochloride was produced by special request from the Los Alamos Laboratory (Los Alamos, CA), which was 60% of the total world supply of 26Al. This was then formulated as [26Al]‐ACH in a simple antiperspirant roll‐on formulation for dermal application to the shaved and unshaved axillae of human volunteers. An i.v. administration was also prepared in order to calculate a measure of fraction absorbed (Fabs). The scarcity of 26Al limited the number of human subjects that could be dosed in a clinical study and the amount of 26Al that can be applied. From the available data, dermal absorption of aluminum was expected to be very low.

A clinical pharmacokinetic study was performed, the objective of which was to obtain a robust measured estimate of the internal dose of aluminum in humans following topical application of a representative 26Al‐antiperspirant formulation, under conditions that reflect real‐life use.

Methods

Production and analysis of 26Al‐labeled ACH

A method to produce 26Al‐labeled ACH was developed for incorporation into an antiperspirant formulation. The method was based on procedures kindly provided by Elementis SRL. In summary, aluminum powder, aluminum chloride (AlCl3) solution, 26Al solution, and water were mixed, while stirring and heated to initiate the reaction. The 26Al‐ACH solution was produced according to the Principles of Good Laboratory Practice (GMP; OECD ENV/MC/CHEM(98)17) and fulfilled the specifications (based on commercially available ACH used in marketed antiperspirant products) for pH, Al:Cl ratio, % chloride, % aluminum, molecular weight profile, and homogeneity of labeling.

The proportion of 26Al:27Al in the ACH test material was 1:820,000 (i.e., 0.138 μg 26Al applied in 113 mg total aluminum) meaning that every atom of 26Al detected would represent 820,000 atoms of aluminum entering the body from the test antiperspirant. The homogeneity of label incorporation (26Al:27Al) was confirmed across molecular weight bands, with mean radioactive concentration 116.8 Bq/g. A simple roll‐on test formulation was prepared containing 25% 26Al‐ACH (6.25% Al), thickened with 0.625% hydroxyethylcellulose to achieve typical commercial viscosity. A commercially available roll‐on antiperspirant containing non‐radiolabeled 27ACH was used during the “daily use” phases of the study on days before and after the radiolabeled dose.

The aluminum citrate solution to be administered intravenously was prepared according to the GMP at the GMP hot laboratory of the department of Radiology & Nuclear Medicine of the VUmc (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). In summary, 26Al in 1 M HCl was diluted with citrate/acetate buffer (pH 4) in a laminar flow unit class A. The product was dispensed from the 300 mL stock solution and filter‐sterilized using a 0.22 μM filter. After dispensing, the vials were sterilized by autoclave (20 minutes at 121°C). The process was validated with three consecutive batches and the production process was approved by the qualified person prior to the production of the final batch used for human application. The procedure for the preparation of the i.v. aluminum citrate formulation was fully described in the Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier.

Clinical study design

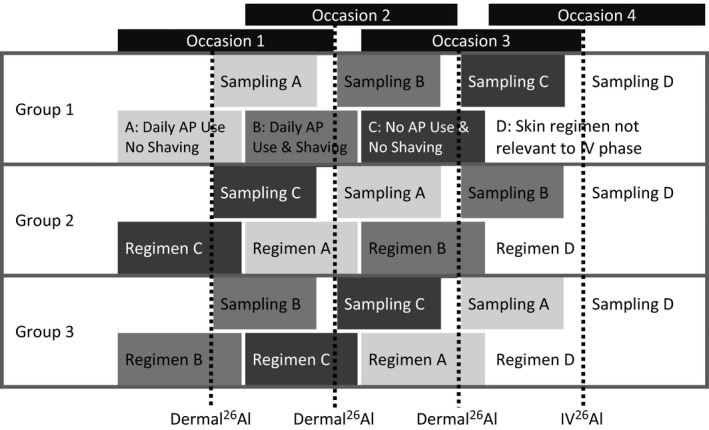

The clinical study was designed as a single‐center, randomized, open‐label, longitudinal crossover study, conducted in The Netherlands (Centre for Human Drug Research (CDHR), Leiden; see Figure 1). Twelve healthy women (23–39 years of age, body mass index within 19.3–27.3 kg/m2) were included for a total study period of 24 weeks; 11 completed the study and one withdrew prior to the i.v. administration as she became pregnant during the study. Subjects were required to be used to frequent (at least three times a week) wet shaving using an appropriate female safety razor (electric shaving not being allowed). Exclusion criteria were, among others, clinically significant abnormality of the axilla as determined by physical examinations (e.g., scars, cuts, wounds, tattoos, and/or dermal abnormalities); use of aluminum‐containing medications prior to and during the course of the study; and axillary hyperhidrosis (including subjects treated for this conditions (e.g., with Botox). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Board Brabant (The Netherlands) ABR number NL49088.028.14 and informed consent was obtained from all volunteer participants prior to the start of the study.

Figure 1.

The basic crossover study design for three groups of four human volunteers showing the randomization of the three occasions of dermal product use and shaving regimens followed by the fourth occasion of i.v. dosing, each occasion of dosing with an extremely rare isotope of aluminum (26Al) has a sampling period that overlaps with the adaptation phase of the subsequent regimen. The dosing phases are as follows: A – topical application of 26Al‐chlorohydrate (ACH) after daily use of Al‐containing antiperspirant (AP) without shaving, representing typical repeated exposure; B – topical application of 26Al‐ACH after daily use of Al‐containing antiperspirant and daily shaving, representing repeated exposure with worst‐case daily shaving behavior; C – topical application of 26Al‐ACH without daily use of Al‐containing antiperspirant without shaving, representing single exposure, to allow direct comparison with a previous human study4; D – i.v. administration (at 1/100th the topical 26Al dose) of 26AlCl3 for the assessment of Fabs.

Four treatment periods were included in the study (see Figure 1).

Prior to each of the three topical treatments with 26Al‐ACH, a 4‐week adaptation was scheduled depending upon which treatment group the subjects were allocated to (e.g., to apply unlabeled antiperspirant and/or whether or not to shave on a daily basis). There were four subjects per group, and each subject served as their own control. All subjects were treated with an i.v. dose (D) at the end of the study.

The 26Al‐labeled formulation was applied to both axillae within a delineated area of ~100 cm2 per armpit. An amount of 1.5 g/day of the test formulation (6.25% Al; 25% 26Al‐ACH; 50 Bq 26Al/axillae) was applied to each axilla using positive displacement pipette.

After topical application of the 26Al‐ACH antiperspirant, a cotton T‐shirt was dispatched to the subjects to wear for the rest of the day and during the night to minimize loss of radiolabel to the environment. Twenty‐four hours after application, the subjects were instructed to take a shower and to wash their axillae. To establish a pharmacokinetic profile, blood samples were collected at various time points up to 35 days after application. Whole blood samples were analyzed (not plasma) to avoid any potential impact of protein binding in the analysis. Samples were taken at T = predose, 5, 15, 30 minutes, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 hours, then 3, 4, 8, 15, 22, and 29 days postdose administration. To provide some evidence on urinary excretion, spot urine samples were taken in the study at 24 hours, 3, 4, 18, 15, 22, and 29 days postdose and normalized to creatinine concentration.

Blood and urine analysis of 26Al by AMS

All blood and urine samples collected in the clinical study were analyzed for 26Al content by AMS (1 MV Tandetron Accelerator Mass Spectrometer, model 4100B0, purchased from High Voltage Engineering, The Netherlands). This approach had been used previously for oral aluminum absorption.5 An AMS method for the detection of 26Al in human blood and urine samples was developed and qualified by determining the parameters of selectivity, linearity, accuracy, precision, and lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ). In brief, the technical settings were optimized for charge stage (3+), Cesium temperature in the ion source (115°C), and target and extraction cone voltages (7 and 28 kV). As biological samples contain a relatively high concentration of magnesium (Mg), this could negatively influence AMS analysis due to similar mass (m = 26). The interference was found to be negligible, as 26Al ion count was not significantly altered in the detector, when the matrices were spiked with up to 10 times the natural levels of Mg. The biological samples, containing aluminum as a complex with chloride, were processed to convert the aluminum chloride into aluminum oxide (Al2O3), as this was considered the most optimal sample composition for AMS. Previously published approaches for the oxidation of aluminum were very elaborate and time‐consuming, using acid digestion followed by oxide precipitation. One reason for such a complicated sample preparation method was to minimize AMS sample contamination with Mg material. Because it was shown that even very high levels of Mg did not influence the quality of the results, a more straightforward sample oxidation procedure was developed. Briefly, clinical samples were transferred to a porcelain crucible and a fixed amount of 27Al solution was added. Next, the samples were slowly heated in a stepwise approach in a graphite furnace for oxidation (total time for oxidation was 14 hours). After cooling of the oxidized sample, the powder was collected from the crucibles and mixed with powdered silver (1:4), and then the mixture was pressed in copper targets for AMS analysis.

Urine analysis of 27Al by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

Additionally, all urine samples were analyzed for 27Al content by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP‐MS). The ICP‐MS analysis was performed using Rhodium (m/z 103) as internal standard. Samples were dissolved in 1 mL nitric acid (concentrated) and demineralized water and subsequently analyzed on an Element 2 (Thermo Fisher) at medium resolution.

Data analysis

Using 26Al/27Al isotope ratios, a linear regression model with a weighting factor of 1/x2 was used to determine the calibration curves. Concentrations in mBq/mL were then converted to g Al/mL based on the specific activity for 26Al of 62.9 MBq/g.

Blood concentration‐time areas under the curve (AUC) were determined using the trapezoid method (linear up and log‐linear down method). The areas for time intervals before reaching the maximum concentration and time intervals below LLOQ are calculated as:

The areas for time intervals after maximum concentration are given by:

For the intravenous administration, only the log‐linear equation was used. The area from the last time point to infinity was calculated as:

where k el is the elimination rate constant, derived as the (absolute value of the) slope of the log‐concentration‐time curve of the last four time points (168–672 hours). AUC0–∞ are calculated for each subject and each treatment. The Fabs was calculated as the ratio of dermal to i.v. AUC for each topical application scenario, then averaged over subjects to get a mean Fabs and SD per scenario.

The fraction of dose excreted in urine was estimated using the following steps:

For each day of urine sampling for each subject, the 24‐hour urine production (l/day) is estimated by dividing the typical creatinine excretion of 10 mmol/day by the measured creatinine concentration (mmol/l) in the urine sample.6

Each measured 26Al concentration is multiplied by the 24‐hour urine production and divided by the applied dose to derive the fraction of the dose excreted in that 24‐hour window.

For the topical administration data, urinary concentrations on days without sampling are estimated by linear interpolation between the surrounding days on which a urine sample was taken, and multiplied by the average of all 24‐hour urine productions of the subject, and taken for further calculations as described above.

For the i.v. administration data, the amount of 26Al excreted on days without sampling is log‐linearly interpolated between days on which a urine sample was taken, and taken for further calculations as described above.

Daily fractions of the dose excreted are summed to a cumulative total fraction of the dose excreted in urine within the treatment period.

Results

Safety and tolerability

All four treatments (see Figure 1) were well tolerated by the subjects. No clinically relevant changes in clinical laboratory measures, vital signs or electrocardiogram measures were observed upon topical application or i.v. administration of test materials. A total of 55 adverse events were reported during the study period (Table 1); the reported adverse events that were considered to be possibly or probably related to study treatment (n = 10) were of mild severity. During topical administration there were two instances of rash/pruritus, both considered to be possibly treatment related. Mild paresthesia was observed in 7 of 11 subjects upon i.v. injection of labeled aluminum, along with one instance of salivary hypersecretion also considered to be possibly treatment related. No serious adverse events occurred in this study. Eleven subjects completed the study.

Table 1.

Summary of emergent adverse events by relationship, intensity and system organ class

| Relationship | Intensity | System organ class (number) |

|---|---|---|

| Probably | Mild | Paresthesia (7) |

| Possibly | Mild | Pruritus/rash (2); salivary hypersecretion (1) |

| Unlikely | Mild | nausea (1) |

| Unrelated | Moderate | Urinary tract infection (1); facial bone fracture (1) |

| Mild | Infections (16); headache/paresthesia (10); gastrointestinal disorders (6); general disorders (5); epistaxis (2); injury (1); musculoskeletal chest pain (1); pregnancy (1) |

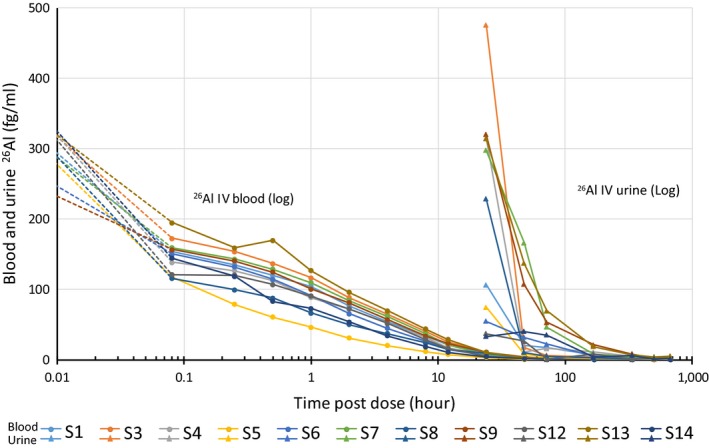

Blood analysis of 26Al using AMS

In total, 732 whole blood samples were analyzed for 26Al content by AMS. Following i.v. administration, 26Al had declined to very low levels after 24 hours but could be detected up to 28 days after administration in 6 of 11 subjects (Figure 2). Based on these data, the mean AUC for the i.v. route was calculated to be 1,273 ± 466 hours × fg/mL. All blood samples collected after topical application gave results below the LLOQ (0.12 fg 26Al/mL) except for two samples (treatment B, subject 11 = 2 hour's value: 0.13 fg 26Al/mL; and treatment C, subject 7 = 6 hour's value: 0.14 fg 26Al/mL).

Figure 2.

Blood (circles) and urine (triangle) measurement (fg/mL) of an extremely rare isotope of aluminum (26Al) following i.v. dosing in 11 human volunteers: subjects 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, and 14. Note the logarithmic scale.

Urine analysis of 26Al using AMS

In total, 384 spot urine samples were analyzed for 26Al content by AMS and were additionally assayed for creatinine concentration. For urine, a much higher number of samples (31%) contained quantifiable 26Al concentrations following topical application, thereby providing more reliable data as input for noncompartmental analysis of urinary excretion of 26Al. Morning spot urine samples were normalized for creatinine concentration using a mean creatinine excretion of 10 mmol/day.6 The LLOQ in urine samples was analyzed to be 61 ag/mL and additionally, the limit of detection (LOD) was calculated to be 34 ag/mL. For urine data, values below the LLOQ and above the LOD were replaced by half the LLOQ; whereas values below LOD were replaced by half the LOD. There was no observable impact on the rate or extent of aluminum absorption with shaving or daily dosing of normal antiperspirant (i.e., there was no statistical difference among treatment groups A, B, and C). The values for spot urine measurements taken from 24 hours onward following i.v. dosing are shown in Figure 2.

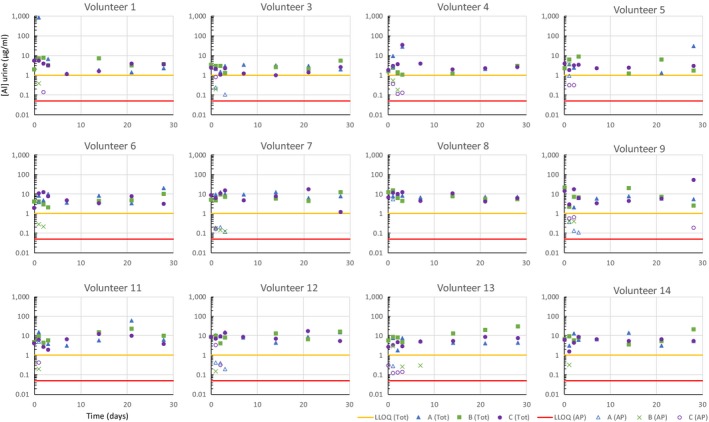

Urine analysis of 27Al using ICP‐MS

In total, 384 spot urine samples were analyzed for 27Al by ICP‐MS. Background levels of total 27Al in urine from all daily exposure sources are shown in Figure 3. Average levels of 27Al in urine of 9.5 μg 27Al/l were consistent with the published German Human Biomonitoring Commission reference value of 15 μg Al/l.7 Although urinary aluminum levels varied substantially between subjects, and over time within each subject, there was no difference between dermal phases A and B, where 27Al containing antiperspirants use was mandatory, and dermal phase C where antiperspirant use was prohibited. There was also no obvious impact of applying the test antiperspirant formulation (6.25% Al) at the 90th percentile amount (1.5 g in total).

Figure 3.

Comparison of total aluminum excretion measured in spot urine samples measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (μg/L), along with the calculated contribution from the an extremely rare isotope of aluminum (26Al) labeled antiperspirant (expressed in μg/l total aluminum, calculated from the 26Al excretion measured by accelerator mass spectrometry AMS, according to the ratio of 26Al:27Al in the labeled antiperspirant), for each of the 12 human volunteers, measured in spot samples days after dosing (note volunteers 2 and 10 were recruited in reserve and did not receive treatments with 26Al). The yellow line on each graph represents the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 1 μg/l for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry ICP‐MS measurement of total aluminum. The red line is 0.049 μg/l, calculated for the antiperspirant derived aluminum and equivalent to the LLOQ of 0.06 fg/l for 26Al measured by AMS).

Fraction absorbed

The Fabs was defined as the ratio of cumulative fractions of the dose excreted between topical and i.v. applications. This ratio was derived for each topical application scenario for each subject, and then averaged over subjects. For those blood samples that were below the LLOQ, a value was used as half the value of the LLOQ rather than zero. This was consistent with an approach as described by the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety in its report on aluminum.8 Following this approach, and using blood analysis, results in an estimated mean percentage absorbed at 0.0221 ± 0.0123% (Table 2). As the vast majority of samples were below LLOQ, replacing them by half the LLOQ value likely results in an overestimation of true absorption.

Table 2.

Percentages of the applied topical dose absorbed following three different topical treatment periods, and all data taken together, as calculated by noncompartmental methods from (1) blood data and (2) urinary excretion data

| Treatment | A | B | C | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Noncompartmental methods from blood data | ||||

| Mean | 0.0198 | 0.0260 | 0.0206 | 0.0221 |

| SD | 0.0077 | 0.0185 | 0.0076 | 0.0123 |

| CV (%) | 39 | 71 | 37 | 55 |

| Min | 0.0131 | 0.0114 | 0.0131 | 0.0114 |

| Max | 0.0354 | 0.0759 | 0.0361 | 0.0759 |

| (2) Noncompartmental methods from urinary excretion data | ||||

| Mean | 0.0078 | 0.0081 | 0.0122 | 0.0094 |

| SD | 0.0064 | 0.0113 | 0.0192 | 0.0131 |

| CV (%) | 81 | 140 | 158 | 140 |

| Min | 0.0021 | 0.0022 | 0.0020 | 0.0020 |

| Max | 0.0200 | 0.0410 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 |

Mean, SD, coefficient of variation (CV %) and minimum and maximum observation among 11 subjects are given.

A = daily use of antiperspirant without shaving; B = daily use of antiperspirant and daily shaving; C = no use of daily antiperspirant without shaving.

Using the urine analysis, the mean values calculated for Fabs are shown in Table 2 and the individual data are shown in Table 3. For those urine samples that were below the LLOQ, a value was used as half the value of the LLOQ rather than zero. Taking all data into account and recognizing the uncertainty in the approach using one half the LLOQ data, the fraction absorbed for all topical treatment periods, based on 26Al concentrations in urine, was estimated to be of the order 0.002–0.06%, with a mean estimate of 0.0094%.

Table 3.

Best‐case, worst‐case and the “Norwegian” half LLOQ approach to providing an estimate of % absorbed for individual subjects using the urine data

| Best‐case estimatea | Norwegian half LLOQ‐based estimateb | Worst‐case estimatec | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | A/D | B/D | C/D | No. | A/D | B/D | C/D | No. | A/D | B/D | C/D |

| 1 | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | 0.0333 | 1 | 0.0028 | 0.0035 | 0.0350 | 1 | 0.0048 | 0.0061 | 0.0366 |

| 3 | 0.0028 | 0.0012 | 0.0022 | 3 | 0.0041 | 0.0032 | 0.0042 | 3 | 0.0055 | 0.0053 | 0.0062 |

| 4 | 0.0065 | 0.0021 | 0.0031 | 4 | 0.0085 | 0.0041 | 0.0046 | 4 | 0.0105 | 0.0062 | 0.0061 |

| 5 | 0.0108 | 0.0363 | 0.0022 | 5 | 0.0169 | 0.0410 | 0.0088 | 5 | 0.0229 | 0.0456 | 0.0155 |

| 6 | 0.0127 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 6 | 0.0145 | 0.0042 | 0.0026 | 6 | 0.0162 | 0.0059 | 0.0051 |

| 7 | 0.0019 | 0.0012 | 0.0010 | 7 | 0.0031 | 0.0022 | 0.0020 | 7 | 0.0042 | 0.0032 | 0.0030 |

| 8 | 0.0167 | 0.0004 | 0.0010 | 8 | 0.0200 | 0.0041 | 0.0036 | 8 | 0.0234 | 0.0077 | 0.0062 |

| 9 | 0.0026 | 0.0043 | 0.0039 | 9 | 0.0031 | 0.0050 | 0.0047 | 9 | 0.0036 | 0.0057 | 0.0055 |

| 12 | 0.0051 | 0.0006 | 0.0611 | 12 | 0.0066 | 0.0030 | 0.0625 | 12 | 0.0082 | 0.0055 | 0.0639 |

| 13 | 0.0010 | 0.0131 | 0.0018 | 13 | 0.0021 | 0.0140 | 0.0026 | 13 | 0.0031 | 0.0149 | 0.0034 |

| 14 | 0.0011 | 0.0016 | 0.0000 | 14 | 0.0045 | 0.0046 | 0.0033 | 14 | 0.0079 | 0.0077 | 0.0065 |

| Best‐case estimatea | Norwegian half LLOQ‐based estimateb | Worst‐case estimatec | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | A | B | C | All | Scenario | A | B | C | All | Scenario | A | B | C | All |

| Mean | 0.0056 | 0.0058 | 0.0100 | 0.0071 | Mean | 0.0078 | 0.0081 | 0.0122 | 0.0094 | Mean | 0.0100 | 0.0103 | 0.0144 | 0.0116 |

| SD | 0.0055 | 0.0107 | 0.0195 | 0.0129 | SD | 0.0064 | 0.0113 | 0.0192 | 0.0131 | SD | 0.0075 | 0.0121 | 0.0191 | 0.0134 |

| %CV | 97 | 184 | 195 | 181 | %CV | 81 | 140 | 158 | 140 | %CV | 75 | 117 | 133 | 116 |

| Min | 0.0007 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Min | 0.0021 | 0.0022 | 0.0020 | 0.0020 | Min | 0.0031 | 0.0032 | 0.0030 | 0.0030 |

| Max | 0.0167 | 0.0363 | 0.0611 | 0.0611 | Max | 0.0200 | 0.0410 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | Max | 0.0234 | 0.0456 | 0.0639 | 0.0639 |

CV, coefficient of variation; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification; LOD, limit of detection. aBest‐case Estimate: all values below LLOQ are treated as true zero concentrations. bNorwegian Half LLOQ Based Estimate: all values below LOD are replaced by half of the LOD; all values between LOD and LLOQ are replaced by half of the LLOQ. This approach was used by the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety in its report on aluminium.10

cWorst‐case Estimate: all values below LOD are replaced by the LOD; all values between LOD and LLOQ are replaced the LLOQ.

Discussion

In this study, using state‐of‐the‐art techniques, we present a refined estimate of aluminum dermal absorption. Human skin absorption of aluminum has been studied previously: an in vitro study was performed by Pineau et al.9 using ex vivo human skin with 27Al delivered in antiperspirant formulations and a limited single dose in vivo human study has also been performed by Flarend et al.,4 both deemed by regulators as not reliable.

In Pineau et al.,9 the measured amounts of aluminum in the receptor fluid were negligible and close to the figures recorded with blank samples. Nonradioactive 27Al was used rather than radioactive 26Al that would have enabled greater sensitivity and more accuracy for measurement of such low levels of absorption. Mass balances varied from 51 ± 10% to 141 ± 29%, which is not compliant with SCCS criteria10 for valid in vitro mass balance skin absorption studies and the data are of questionable human relevance (for example, the ex vivo skin is not capable of physiological sweating).

The new study reported here was designed based on the preliminary findings by Flarend et al.4 In that study, ~13 mg Al, containing 6 Bq 26Al, formulated in a 21% ACH solution, was applied to the left axilla in one male and one female subject. In selected blood samples, 26Al could be detected at very low levels by AMS; however, the concentrations found were too low to provide solid quantitative data. In urine, 26Al was detected in the first day and continued for at least 44 days. Most of the urinary excretion occurred over the first 2‐week postexposure. Of the applied aluminum, 0.0082% and 0.016% was eliminated in urine from the male and female subjects, respectively. Based on this, following correction for 85% renal excretion,11 Flarend et al.4 estimated that 3.6 μg would be absorbed from the single application of antiperspirant, equivalent to 0.012% of the applied dose. The remaining aluminum was either lost into the environment when the bandages came loose, or was retained as precipitating plugs on the sweat ducts.

In the study reported here, a similar LLOQ of 26Al in blood (0.12 fg/mL) to that seen by Flarend et al.4 was achieved. It was anticipated that the application of a 16‐fold higher dose of radioactivity (~100 Bq of 26Al), applied to both axillae, would result in quantifiable blood levels. Unexpectedly, hardly any measurable concentrations in the blood samples after topical application were found, except for two samples that had values (0.13 and 0.14 fg/mL) just above the LLOQ. This meant that, similar to Flarend et al.,4 estimation of Fabs from the dermal route had to rely here on using the urine data, where 31% of samples had quantifiable levels of 26Al.

Creatinine adjusted spot urine samples at 24 hours had been collected as a backup, because blood samples were the primary focus of the study. Using the i.v. data as a benchmark, the calculations assume that the quantity in the spot urine sample only represents 5–20% of the systemically available dose, which means that the amount absorbed in the dermal phases is substantially overestimated. In hindsight, a total 24‐hour urine collection would have provided a better measure, but the primary aim at the beginning of this study was to rely on expected measures in blood. Although creatinine correction can be used to correct spot urine samples for differences in urine volume output between volunteers and time points, it cannot correct for the aluminum concentrations that would have been excreted in bladder voiding prior to the 24‐hour spot test. This means that the quantity of aluminum excreted in the early part of the first 24 hours is unknown, as is the time since last urination prior to the spot urine sample collection. For the i.v. doses, the impact of missing the first 12 + hours of excretion is substantial because the majority of the i.v. dose of 26Al is lost from the blood in the minutes and hours postdose (Figure 2), meaning that using 24‐hour spot urine to estimate i.v. dose is likely to substantially underestimate internal exposure. For the dermally applied samples, the impact is likely much smaller because the absorption kinetics across the skin would be slower, meaning the 24‐hour spot urine samples would better reflect internal exposure. Because the i.v. data are the benchmark for assessing Fabs in this study design, the uncertainty introduced by using spot urine measurements would overestimate true dermal absorption.

It is generally accepted that the urinary route is the prevailing route of aluminum clearance with an unknown amount excreted in feces.11 Therefore, urine data are a reliable basis for estimating aluminum exposure. In addition, as the same subjects underwent both topical and i.v. dosing, each person acted as their own control and there is no need to account for any interindividual variation between topical and i.v. dosing. Using the half LLOQ‐based method8 to account for uncertainties, the estimated fraction of aluminum absorbed was 0.002–0.06%, with a mean estimate of 0.0094%. Interestingly, a similar estimate of 0.0092% was found when the actual measured data below the LLOQ were included. Although the use of samples below the LLOQ introduces additional uncertainty, the results are consistent with the Norwegian half LLOQ‐based approach, which is adequately conservative. A similar result was seen in blood samples; the percentage absorbed, calculated including the blood concentrations that were as measured below the LLOQ, were found to be 0.0105%.

In addition to measuring 26Al by AMS for the absolute bioavailability determination, total 27Al was measured in urine samples using ICP‐MS. This “background” aluminum in the body represents overall exposure from food, drink, and endogenous and other environmental sources.12 These total aluminum measurements provide an additional line of evidence to suggest antiperspirants make only a minor contribution to systemic exposure because there was no observed impact on systemic total aluminum levels during clinical phases where daily antiperspirant use was mandatory (phases A and B) or prohibited (phase C).

The absolute bioavailability method has, together with the rare 26Al radioisotope, provided a useful investigative tool for determining the skin absorption of aluminum under real‐life conditions. Future investigations of this type should consider 24‐hour urine collection, ideally with higher sampling resolution, and consider increasing the dermal dose of radiolabel by increasing the ratio of 26Al:27Al in the dermally applied test material. Because, from the measurable urine samples (31% of all samples), the present study saw no apparent difference between the various treatments (shaving or daily use) any future investigations could be simplified to a single phase including shaving and daily use.

Funding

This study at TNO, The Netherlands was 100% funded by Cosmetics Europe. Camilla Alexander‐White was funded as an independent toxicology consultant by Cosmetics Europe to support the Cosmetic Europe Aluminum Consortium.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Author Contributions

R.d.L., W.V., and C.A.‐W. wrote the manuscript. R.d.L. and W.V. designed the research. E.v.D., D.G., S.B., K.B., B.W., P.A.M.P., and G.A.v.d.L. performed the research. E.v.D., D.G., S.B., K.B., B.W., C.A.‐W., P.A.M.P., and G.A.v.d.L. analyzed the data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Department of Energy because the 26Al used in this research were supplied by the United States Department of Energy Office of Science by the Isotope Program in the Office of Nuclear Physics. We would also like to thank Wim Meuling (Clinical and Hands‐on Services) for his scientific advice in relation to this study. We thank Elementis SRL for the provision of reagents used to prepare ACH formulations.

References

- 1. Draelos, D.Z. Antiperspirants and the hyperhidrosis patient. Dermatol. Ther. 14, 220–224 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poirier, J. et al Double‐blind, vehicle‐controlled randomized twelve‐month neurodevelopmental toxicity study of common aluminum salts in the rat. Neuroscience 193, 338–362 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. SCCS . Opinion on the safety of aluminium in cosmetic products.; 2014. Contract No.: SCCS/1525/14 Revision of 18 June 2014.

- 4. Flarend, R. , Bin, T. , Elmore, D. & Hem, S.L. A preliminary study of the dermal absorption of aluminium from antiperspirants using aluminium‐26. Food Chem. Toxicol. 39, 163–168 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steinhausen, C. et al Investigation of the aluminium biokinetics in humans: a 26Al tracer study. Food Chem. Toxicol. 42, 363–371 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang, S.T. , Pizzolato, S. & Demshar, H.P. Aluminum levels in normal human serum and urine as determined by Zeeman atomic absorption spectrometry. J. Anal. Toxicol. 15, 66–70 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schulz, C. , Angerer, J. , Ewers, U. & Kolossa‐Gehring, M. The German Human Biomonitoring Commission. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 210, 373–382 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. VKM Norwegian scientific Committee for Food Safety , Risk assessment of the exposure to aluminium through food and the use of cosmetic products in the Norwegian population. (2013).

- 9. Pineau, A. , Guillard, O. , Favreau, F. , Marrauld, A. , Fauconneau, B. In vitro study of percutaneous absorption of aluminum from antiperspirants through human skin in the Franz™ diffusion cell. J. Inorg. Biochem. 110, 21–26 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. SCCS . The SCCS notes of guidance for the testing of cosmetic ingredients and their safety evaluation. 9th revision.; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. Priest, N.D. The biological behaviour and bioavailability of aluminium in man, with special reference to studies employing aluminium‐26 as a tracer: review and study update. J. Environ. Monit. 6, 375–403 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. European Food Standards Agency . Safety of Aluminium from dietary intake. EFSA J. 754, 1–34 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]