Abstract

In the following brief report, we examined gender differences in incidence rates of any dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) alone, and non-Alzheimer’s dementia alone in 16,926 women and men in the Swedish Twin Registry aged 65+. Dementia diagnoses were based on clinical workup and national health registry linkage. Incidence rates of any dementia and AD were greater in women than men, with any dementia rates diverging after age 85 and AD rates diverging around 80. This pattern is consistent with women’s survival to older ages compared to men. These findings are similar to incidence rates reported in other Swedish samples.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, any dementia, gender differences, incidence, Swedish Twin Registry

INTRODUCTION

Two-thirds of clinically diagnosed cases of dementia and AD are women, according to U.S. [1] and most European reports. The primary reason offered for this gender difference is women’s greater longevity [2], as risk of developing dementia increases with age. In spite of this proposed explanation, the extent to which gender differences are primarily a matter of the increasing number of women relative to men at older ages or also of women’s having a greater risk than men at the same age remains to be resolved. The extant literature is far from conclusive, consisting mainly of plausible hypotheses about sex-specific biological and gender-specific sociocultural factors that might increase women’s vulnerability over men’s [3–5]. Ultimately, understanding gender-specific trends in dementia and AD may point to preclinical factors that might lower risk of onset differentially in men and women [6]. In the present study, we examine differences between men and women in risk of any dementia, AD alone, and non-AD dementia (NAD) alone by looking at incidence density rates by age and gender.

The higher number of AD or dementia cases among women is often taken to suggest that women have a higher incidence. Yet, a closer inspection of the literature reveals a more complicated account. First, few studies report statistically significant gender differences in incidence rates [6]. Second, meta-analysis has not clarified similarities and differences in rates across international samples [7]. In European samples, several studies have observed gender differences [8–11] whereas the majority do not [12–16]. Gender differences also are observed in U.S. samples [17–20], although again some do not observe them [21–23] or observe them where they previously did not [24, 25].

Irrespective of statistical significance, many studies descriptively suggest gender differences. Incidence rates in women consistently were higher than men in numerous European and U.S. samples [9, 12, 14, 16, 18, 24, 26–31]. Small samples may explain the lack of significant differences between men and women in these studies [24]. Pooling samples in meta-analyses to increase sample size generally demonstrates significant gender differences in AD incidence [7, 32, 33]. One exception, however, is a recent pooled analysis [34] that concluded no gender differences in AD risk between age 55 and 85.

Where gender differences have been observed, they tend to be observed later in life, with the inflection point at which rates begin to differ between men and women also varying by study. While most studies support a pivot age at approximately 80 years old—in which incidence rates in women either switch position with or climb above men’s rates [17–20, 23–25, 35, 36]—there is quite a bit of variability. Previous studies have reported incidence rates that begin to diverge as early as 75–79 years (the Baltimore Longitudinal Study [37]) and as late as 90+ (Kungsholmen Project [8]).

The aim of the current report is to contribute to this literature by tracing annual incidence density rates of older adult participants in the Swedish Twin Registry (STR) to evaluate whether and at what age rates of newly diagnosed cases of dementia are higher in women than men. Using the STR offers several benefits, including a large sample from a single source; the ability to link to administrative records; and the application of uniform methodology to estimate incidence rates for men and women across a broad range of ages. Incidence rates that do not differ by gender would suggest that the greater number of dementia cases in women must be largely a function of their greater longevity, with more women than men surviving long enough to become demented. If incidence rates do differ by gender, survival remains one among many explanations ranging from genetic to environmental causes [17].

METHODS

Sample

The sample was drawn from four different studies of Swedish older adults, all sampled from the STR [38] and all born between 1895 and 1935:1 cross sectional census of all twins in the STR aged 65 and older at the time of study and three longitudinal studies that followed representative sub groups within the STR from the same birth cohort. Some individuals participated in both a longitudinal study and the cross-sectional assessment (described in the Supplementary Material); each was included in the sample only once, but drawing data from both studies combined. In all, 17,349 individual twins were included in the current sample. At first assessment, mean age of men was 71.40 years (SD = 8.75) and mean age of women was 72.61 years (SD = 9.13), with 16.87% of the sample with a final study age of 85 years or greater (n = 2,927). Sample sizes are presented in Table 1 for the total sample and Supplementary Table 1 for individual STR studies.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of any dementia and Alzheimer’s disease for men and women

| Any Dementia |

AD Only |

Non-AD Dementia |

No Dementia Diagnosis |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | N (%) | Age at onset (SD) | N (%) | Age at onset (SD) | N (%) | Age at onset (SD) | N (%) | Age at onset | N |

| Male | 1386 (18.54) | 79.84 (7.58) | 765 (10.24) | 80.02 (7.86) | 621 (8.31) | 79.62 (7.22) | 6088 (81.46) | – | 7474 |

| Female | 2485 (25.16) | 81.47 (7.53) | 1560 (15.80) | 81.33 (7.71) | 925 (9.37) | 81.69 (7.21) | 7390 (74.84) | – | 9875 |

| Total | 3871 (22.31) | 80.88 (7.59) | 2325 (13.40) | 80.90 (7.78) | 1546 (8.91) | 80.86 (7.28) | 13478 (77.69) | – | 17349 |

Note. Total sample is equal to the sum of the sample sizes of Any Dementia and No Dementia Diagnosis values. Number of individuals diagnosed with AD Only and number of individuals diagnosed with Non-AD Dementia sum to number of individuals diagnosed with Any Dementia.

Dementia assessment

All participants received cognitive screening at each contact. Longitudinal study participants were administered a cognitive test battery including the Mini-Mental State Examination. The cross-sectional census included the TELE cognitive screening measure [39], with an in-person dementia diagnostic workup for those who performed poorly. Additionally, in-person dementia diagnostic assessments were conducted on a control sample who made few screening errors for purposes of validation. For participants who missed a longitudinal wave, telephone cognitive screening was also conducted. For all four studies, a diagnostic consensus board assigned a consensus clinical diagnosis using information from the in-person workup and medical records using DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria for dementia, and NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for AD [40]. The same consensus protocols were used across all four studies.

Those not in a longitudinal study or otherwise lost to follow-up were followed by registry linkage, using individual-level data from the Swedish National Patient Register (NPR) and Cause of Death Register (CDR). Registries contained International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes for dementia diagnoses (provided in the Supplementary Material). Of the 3,871 individuals with a dementia diagnosis, 2,325 were diagnosed with AD and 1,546 with another form of dementia (mainly comprising vascular dementia, mixed type, and dementia not otherwise specified). Follow-up continued until 2014, providing a retrospective cohort design.

Participants designated as not having dementia (n = 13,478) were those who were determined to be cognitively normal through participation in at least 1 data collection by a longitudinal study or through the cognitive screening of the entire STR. All others were excluded from the current study sample (n = 423).

Age at onset

Individuals who were clinically diagnosed with dementia received an age at onset based on information collected during their in-person clinical assessment. For individuals whose diagnosis came from the NPR, age at onset was inferred by subtracting three years from NPR date of discharge, which is a conservative estimate given that other analyses of the STR data have established that onset typically is five years before diagnoses appear in the NPR [41]. For individuals whose diagnosis came from the CDR, age at onset was designated as three years prior to date of death [41] plus a small amount of normally distributed random “noise” [N(0,0.66)] to model natural occurring variability in onset.

Data analysis

Incidence rates for dementia were calculated for all individuals using person-years [36]. Participants were determined to be cognitively intact at baseline based on in person evaluation, assessment age ≤60, or no registry diagnosis of dementia. Crude rates were estimated by dividing the number of newly diagnosed individuals by the total number of person-years at risk for every year from age 60 to age 100. Newly diagnosed cases were based on age at onset. Rates are expressed per 1000 person-years, with number of years lived past age 60 serving as the time scale (i.e., start of the study window). Age 60 was selected as the “point of entry” to capture the 5-year period prior to the phase of risk for late-onset dementia. Person years were calculated for demented individuals (cases) and nondemented individuals (controls). Cases contributed 1 person year for every year lived until age of dementia diagnosis. For cases, we estimated disease onset as the midpoint between the last age they were nondemented and their age of onset. Thus, individuals diagnosed at age 72 contributed 1 person year from age 60 until age 71, but at age 72 contributed only 0.5 person year. Person-years contributed from each nondemented individual was 1 additional year for every year lived until age death. Local polynomial regression fitting (loess) was used to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Incidence rates for any dementia, AD alone, and NAD are presented. Where 95% CIs overlap, the results do not support a statistically significant gender difference in incidence rates.

RESULTS

Gender differences in incidence rates of dementia

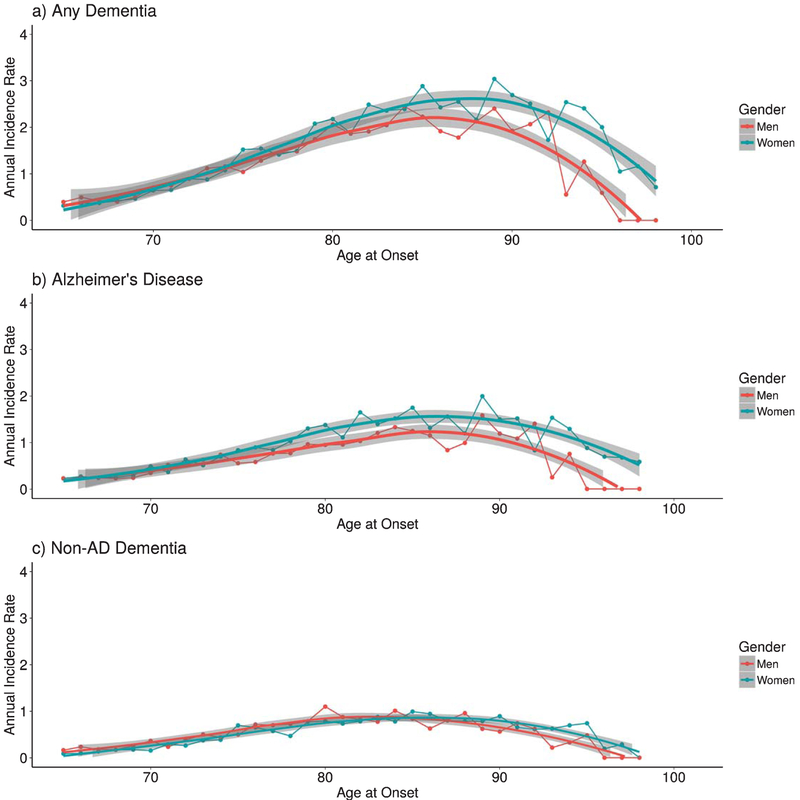

Table 1 presents the proportion of men and women diagnosed with any dementia, AD alone, and NAD alone. Of the 3,871 individuals with a dementia diagnosis, 2,325 were diagnosed with AD and 1,546 with another form of dementia. Women were more likely than men to be diagnosed with any dementia and AD whereas NAD was more equally prevalent. Incidence rates of any dementia for men and women were nearly equivalent until the early 80s, but diverged thereafter and significantly diverged between 85 and 90 years of age (Fig. 1a). Beyond 90, incidence rates for both men and women declined, most likely because of the sparseness of data in old-old age. For AD alone, significant divergence in rates occurred at approximately 80 years of age. Although divergence is visually more prominent at a somewhat younger age (younger than 75), the confidence intervals of the loess lines still overlap (Fig. 1b). For NAD alone, rates are similar between men and women until greater than 90 years of age, at which point women have significantly higher rates than men despite slight visual differences (Fig. 1c). Patterns were similar when incidence rates were traced only with clinically diagnosed cases of dementia as well as separately in the cross-sectional census alone and combined longitudinal samples.

Fig. 1.

Incidence density rates of a) any dementia, b) Alzheimer’s disease, and c) non-AD dementia per 1000 person-years in men and women twins across late adulthood. Loess smoothing lines (with 95% confidence interval) were fit using nonparametric local polynomial regression fitting methods.

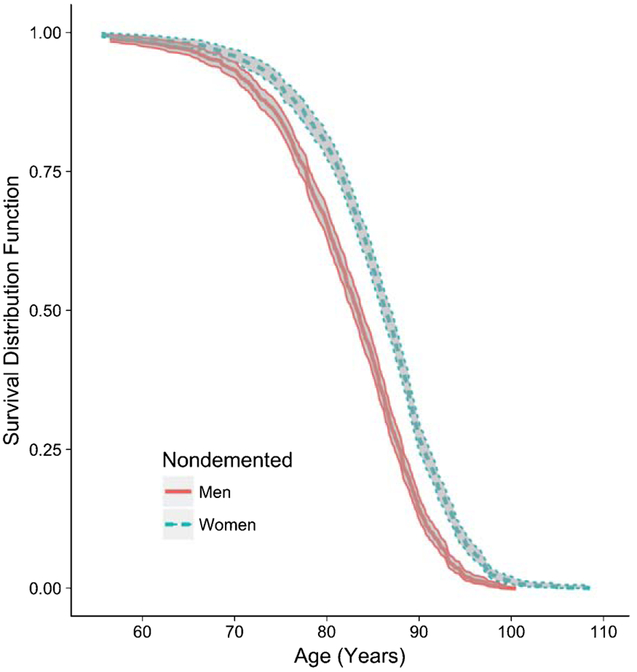

To draw support for the explanation that longevity plays a role in women’s greater incidence rates than men’s at older ages, we estimated survival rates of nondemented men and women. Men had lower likelihood of survival beyond age 90 compared to women (Fig. 2), with women’s survival nearly double men’s and diverging with men’s between ages 70–75.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of nondemented men and women. The exact probabilities of survival beyond age 90.0 are 0.14 for men and 0.27 for women.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological studies present a bewildering impression of gender differences in dementia and AD. Careful review of published data suggests that in most studies, gender differences in incidence rates do not emerge until after age 80. European studies have more consistently reported gender differences; yet, lack of consensus between and within American and European study samples illustrates heterogeneity in rates and ages of divergence in male and female rates. In the current study, any dementia rates were relatively similar until after age 80, with women reaching significantly higher rates than men in the late 80s. For AD alone, women had significantly higher rates of AD starting in the early 80s.

The current results fit well with previous findings in a number of U.S. and European samples [8, 10, 28, 33, 35] where women’s rates were observed to be consistently higher than men’s after age 80, and rates declining in both genders in old-old age. Contrary to previous findings, we found statistically significant differences in AD rates at an earlier age than for any dementia. Women’s survival to longer ages may be one explanation for women’s higher incidence of dementia and AD, possibly. Other explanations may be etiological differences, selective attrition of men due to early mortality attributable to cardiovascular risk factors with a competing risk of death or dementia, and lower thresholds of disease pathology required to produce symptoms [17]. The current results encourage deeper investigation of biological and environmental mechanisms that put women at greater risk compared to men [6].

The combination of clinical and registry-based diagnoses stabilize incidence rates into the early 90s, offering reasonable resolution of gender differences in risk during this period. These results can be safely generalized to nontwin Swedish populations, as they support and extend reports from the Kungsholmen Project [8], and prior research noted similar prevalence rates in the STR compared to other population-based European and U.S. samples [42].

Non-AD dementia rates primarily reflect vascular dementia, but include other dementias and are therefore confounded by differing geneses of pathology. The NAD results are useful in making clear that rates for any dementia mainly represent AD.

The study has several limitations. First, not all dementia diagnoses were made from clinical assessments. However, use of registry-based diagnosis provides reliable identification of dementia and AD cases in the Swedish National Patient Registry [43], with no evidence of gender differences in sensitivity of the registries. Albeit, the registry underestimates true cases and has a sensitivity of about 0.50. Second, secular trends could not be addressed in the current study. Third, a retrospective cohort design was used that included an older population who survived longer to be included in the study, which may have introduced bias attributed to selective mortality from competing causes of death (e.g., cardiovascular disease) and dementia onset between genders in older age groups [17]. Ideally, all data would have come from longitudinal research designs, with all participants non-demented at baseline. The advantage, however, was an increase in power and representativeness.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging T32 AG000037-37 & R01 AG08724 and the Alzheimer Association AARF-17-505302.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/18-0141r2).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180141.

REFERENCES

- [1].Thies W, Bleiler L (2013) 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 9, 208–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mielke MM, Vemuri P, Rocca WA (2014) Clinical epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: Assessing sex and gender differences. Clin Epidemiol 6, 37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Altmann A, Tian L, Henderson VW, Greicius MD (2014) Sex modifies the APOE-related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 75, 563–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Shusterd Lynne T (2014) Oophorectomy, estrogen, and dementia: A2014 update. Mol Cell Endocrinol 18, 1199–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lin KA, Choudhury KR, Rathakrishnan BG, Marks DM, Petrella JR, Doraiswamy PM (2015) Marked gender differences in progression of mild cognitive impairment over 8 years. Alzheimers Dement (NY) 1, 103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Snyder HM, Asthana S, Bain L, Brinton R, Craft S, Dubal DB, Espeland MA, Gatz M, Mielke MM, Raber J, Rapp PR, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC (2016) Sex biology contributions to vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: A think tank convened by the Women’s Alzheimer’s Research Initiative. Alzheimers Dement 12, 1186–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jorm AF, Jolley D (1998) The incidence of dementia: A meta-analysis. Neurology 51, 728–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, von Strauss E, Tontodonati V, Herlitz A, Winblad B (1997) Very old women at highest risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Incidence data from the Kungsholmen Project, Stockholm. Neurology 48, 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ott A (1998) Incidence and risk of dementia. Am J Epidemiol 147, 574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Letenneur L, Gilleron V, Commenges D, Helmer C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF (1999) Are sex and educational level independent predictors of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease? Incidence data from the PAQUID project. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 66, 177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Andersen K, Launer LJ, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, Kragh-Sorensen P, Baldereschi M, Brayne C, Lobo A, Martinez-Lage JM, Stijnen T, Hofman A (1999) Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia: The EURODEM Studies. EURODEM Incidence Research Group. Neurology 53, 1992–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Paykel ES, Brayne C, Huppert FA, Gill C, Barkley C, Gehlhaar E, Beardsall L, Girling DM, Pollitt P, Connor DO (1994) Incidence of dementia in a population older than 75 years in the United Kingdom. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51, 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Boothby H, Blizard R, Livingston G, Mann A (1994) The Gospel Oak Study stage III: The incidence of dementia. Psychol Med 24, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bickel H, Cooper B (1994) Incidence and relative risk of dementia in an urban elderly population: Findings of a prospective field study. Psychol Med 24, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Morgan K, Lilley JM, Arie T, Byrne EJ, Jones R, Waite J (1993) Incidence of dementia in a representative British sample. Br J Psychiatry 163, 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brayne C, Gill C, Huppert FA, Barkley C, Gehlhaar E, Girling DM, DW OC, Paykel ES (1995) Incidence of clinically diagnosed subtypes of dementia in an elderly population. Br J Psychiatry 167, 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chene G, Beiser A, Au R, Preis SR, Wolf PA, Dufouil C, Seshadri S (2015) Gender and incidence of dementia in the Framingham Heart Study from mid-adult life. Alzheimers Dement 11, 310–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Au R, McNulty K, White R, D’Agostino RB Sr (1997) Lifetime risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: The impact of mortality on risk estimates in the Framingham Study. Neurology 49, 1498–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zandi PP, Carlson MC, Plassman BL, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Mayer LS, Steffens DC, Breitner JC (2002) Hormone replacement therapy and incidence of Alzheimer disease in older women: The Cache County Study. J Am Med Assoc 288, 2123–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tom SE, Hubbard RA, Crane PK, Haneuse SJ, Bowen J, McCormick WC, McCurry S, Larson EB (2015) Characterization of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in an older population: Updated incidence and life expectancy with and without dementia. Am J Public Health 105, 408–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Mccann JJ, Beckett LA, Evans DA (2001) Is the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease greater for women than for men? Am J Epidemiol 153, 132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kawas C, Gray S, Brookmeyer R, Fozard J, Zonderman A (2000) Age-specific incidence rates of Alzheimer’s disease: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neurology 54, 2072–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Edland SD, Rocca WA, Petersen RC, Cha RH, Kokmen E (2002) Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence rates do not vary by sex in Rochester, Minn. Arch Neurol 59, 1589–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bachman DL, Wolf PA, Knoefel JE, Cobb JL, Belanger AJ, White LR (1993) Incidence of dementia and probable Alzheimer’s disease in a general population: The Framingham Study. Neurology 43, 515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Teri L, Schellenberg GD, van Belle G, Jolley L, Larson EB (2002) Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence. Arch Neurol 59, 1737–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ruitenberg A, Ott A, Van Swieten JC, Hofman A, Breteler MMB (2001) Incidence of dementia: Does gender make a difference? Neurobiol Aging 22, 575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hagnell O, Lanke J, Rorsman B, Ojesjo L (1981) Does the incidence of age psychosis decrease? Neuropsychobiology 7, 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hagnell O, Ojesjo L, Rorsman B (1992) Incidence of dementia in the Lundby Study. Neuroepidemiology 11(Suppl 1), 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Matthews FE, Stephan BCM, Robinson L, Jagger C, Barnes LE, Arthur A, Brayne C, Comas-Herrera A, Wittenberg R, Dening T, McCracke CFM, Moody C, Parry B, Green E, Barnes R, Warwick J, Gao L, Mattison A, Baldwin C, Harrison S, Woods B, McKeit IG, Ince PG, Wharton SB, Forster G (2016) A two decade dementia incidence comparison from the Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies i and II. Nat Commun 7, 11398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, Bond J, Jagger C, Robinson L, Brayne C (2013) A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: Results of the cognitive function and ageing study i and II. Lancet 382, 1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Paganini-Hill A, Berlau D, Kawas CH (2010) Dementia incidence continues to increase with age in the oldest old the 90+ study. Ann Neurol 67, 114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS (1998) The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55, 809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Launer LJ, Andersen K, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Amaducci LA, Brayne C, Copeland JRM, Dartigues J-F, Kragh-Sorensen P, Lobo A, Martinez-Lage JM, Stijnen T, Hofman A (1999) Rates and risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Results from EURODEM pooled analyses. Neurology 52, 78–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Neu SC, Pa J, Kukull W, Beekly D, Kuzma A, Gangadharan P, Wang LS, Romero K, Arneric SP, Redolfi A, Orlandi D, Frisoni GB, Au R, Devine S, Auerbach S, Espinosa A, Boada M, Ruiz A, Johnson SC, Koscik R, Wang JJ, Hsu WC, Chen YL, Toga AW (2017)Apolipoprotein E genotype and sex risk factors for Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 74, 1178–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Miech RA, Breitner JCS, Zandi PP, Khachaturian AS, Anthony JC, Mayer L (2002) Incidence of AD may decline in the early 90s for men, later for women: The Cache County study. Neurology 58, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Borenstein AR, Wu Y, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Uomoto J, McCurry SM, Schellenberg GD, Larson EB (2014) Incidence rates of dementia, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia in the Japanese American population in Seattle, WA: The Kame Project. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 28, 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kawas CH (2008) The oldest old and the 90+ Study. Alzheimers Dement 4, S56–S59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lichtenstein P, Sullivan PF, Cnattingius S, Gatz M, Johansson S, Carlström E, Björk C, Svartengren M, Wolk A, Klareskog L, de Faire U, Schalling M, Palmgren J, Pedersen NL (2006) The Swedish Twin Registry in the third millennium: An update. Twin Res Hum Genet 9, 875–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Järvenpää T, Rinne O, Räihä I (2002) Characteristics of two telephone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 13, 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jin Y-P, Gatz M, Johansson B, Pedersen NL (2004) Sensitivity and specificity of dementia coding in two Swedish disease registries. Neurology 63, 739–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gatz M, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Berg S, Mortimer JA, Reynolds CA, Fiske A, Pedersen NL (2005) Complete ascertainment of dementia in the Swedish Twin Registry: The HARMONY study. Neurobiol Aging 26, 439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rizzuto D, Feldman AL, Karlsson IK, Dahl Aslan AK, Gatz M, Pedersen NL (2018) Detection of dementia cases in two Swedish health registers: A validation study. J Alzheimers Dis 61, 1301–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.