Abstract

Background

Childhood cancer survivors report poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Modifiable lifestyle factors such as nutrition and physical activity represent opportunities for interventions to improve HRQOL.

Methods

We examined the association between modifiable lifestyle factors and HRQOL among 2,480 adult survivors of childhood cancer in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Dietary intake, physical activity, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption was assessed through questionnaires. Weight and height were measured in the clinic. HRQOL was evaluated using the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short-Form (SF-36). Physical/mental component summary (PCS/MCS) and eight domain scores of HRQOL were calculated. Multivariable linear regression models were used to estimate regression coefficients (β) associated with HRQOL differences.

Results

Being physically active (PCS β=3.10; MCS β=1.48) was associated with higher HRQOL whereas current cigarette smoking (PCS β= −2.30; MCS β= − 6.49) and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) (PCS β= −3.29; MCS β= − 1.61) were associated with lower HRQOL in both physical and mental domains. Better diet (HEI-2015) was associated with higher physical HRQOL (PCS β=1.79). Moderate alcohol consumption was associated with higher physical (PCS β=1.14) but lower mental HRQOL (MCS β= −1.13) (all p-values <0.05). Adherence to multiple healthy lifestyle factors showed a linear trend with high scores in both physical and mental HRQOL (highest vs. lowest adherence: PCS β= 7.60; MCS β= 5.76; p-trend <0.0001).

Conclusion

The association between healthy lifestyle factors and HRQOL is cumulative, underscoring the importance of promoting multiple healthy lifestyles to enhance HRQOL in long-term survivors of childhood cancer.

Keywords: Lifestyle, HRQOL, childhood cancer survivors, nutrition, physical activity

INTRODUCTION

Advances in diagnosis and treatment of childhood cancer have led to rapid growth of the survivor population, now estimated to exceed 450,000.1 However, long-term survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for physical and psychosocial late-effects.2, 3 Maintaining a healthy lifestyle represents an opportunity to decrease these risks. Recent evidence suggests that many childhood cancer patients adopt unhealthy habits during treatment, such as overconsumption of empty calories and becoming sedentary, which may persist into long-term survivorship.4, 5 Poor adherence to nutrition recommendations is reported among adult survivors of childhood cancer,4 and roughly 50% of long-term survivors are not meeting recommendations for physical activity.5

Healthy lifestyle factors have been associated with better health related quality of life (HRQOL) in survivors of adult-onset cancers,6 but evidence regarding their impact on HRQOL of long-term survivors of childhood cancer is still limited. Prior studies that have evaluated HRQOL in association with lifestyle factors focused primarily on physical activity with relatively small sample sizes (n<200).7–10 The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between adherence to multiple modifiable lifestyle factors and HRQOL in a large cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer enrolled in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE) study.

METHODS

Study Population

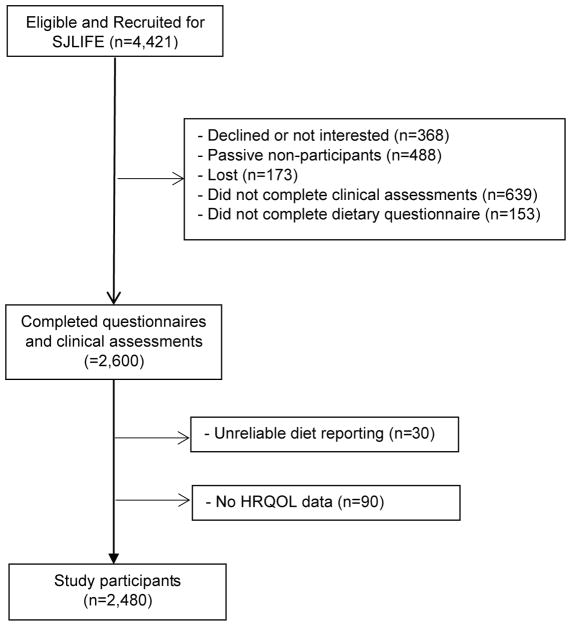

The SJLIFE cohort is comprised of adult survivors of childhood cancer who were treated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) and survived at least 10 years after cancer diagnosis.2, 11 The primary aim of the SJLIFE study is to systematically and prospectively assess health outcomes among childhood cancer survivors as they age. Among 4,421 participants, 2,510 completed comprehensive health questionnaires and clinical assessments at SJCRH. Individuals with unreliable reporting for dietary intake, defined as total caloric intake exceeding three standard deviations above and below the mean value of the natural log-transformed caloric intake in the study population (n=30) were excluded, resulting in 2,480 subjects for analysis (Figure 1). Medical records were abstracted for primary cancer diagnosis and treatment exposures using a previously reported abstraction method.11 All participants provided informed consent for participate in this Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved study.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram

Lifestyle Factors

Diet

Dietary intake was collected using a self-administered Block 2005 Food Frequency questionnaire (FFQ) asking about the usual dietary intake of 110 food items during the past 12 months.12 Diet quality was estimated using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2015 that measures adherence to the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and has 13 components.13 For each component, intake of foods and nutrients is represented on a density basis (per 1,000 kcal). For adequacy components (foods recommended to increase for healthy nutrition: total fruit, whole fruit, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein foods, seafood and plant proteins, and fatty acids), a score of zero is assigned for no intake, and the scores increase proportionately as intake increases to the recommended level. For moderation components (foods recommended to limit for healthy nutrition: refined grains, sodium, and calories from added sugars and saturated fats), intake not exceeding the recommended level is assigned the maximum score and the score decreases as intake increases. The total HEI-2015 score ranges from zero (non-adherence) to 100 (perfect adherence).

Physical Activity

Participants were asked to complete the NHANES Physical Activity Questionnaire that assesses physical activity during the past seven days. Minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity were calculated, with vigorous physical activities weighted at 1.67 per 1 minute.14 Participants were classified as physically active if they met or exceeded 150 minutes per week and physically inactive otherwise, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.15

Weight

Height and weight were measured in the clinic using a wall-mounted stadiometer and an electronic scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms (kg) by height in meters squared (m2), adjusted for amputation status.

Smoking

Current smokers were defined as participants who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and who reported current smoking. Former smokers were defined as participants who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, but who were not currently smoking. Non-smokers reported smoking less than 100 cigarettes during their lifetime.

Alcohol

Nondrinkers were defined as participants who did not drink alcohol in the past 12 months. Moderate alcohol intake was defined as having ≤ 1 drink/day for women and ≤ 2 drinks/day for men. High alcohol intake was defined as having >1 drink/day for women and >2 drinks/day for men.16

Adherence to Multiple Lifestyle Factors

To evaluate the cumulative effect of adherence to multiple healthy lifestyle factors, a total adherence score was created for five modifiable lifestyle factors (Supplemental Table 1). Selection and scoring of lifestyle factors was based on the American Cancer Society’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors.17 For physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption, a value of 1 was assigned if the survivor met the guidelines and 0 otherwise. For diet, a value of 1 was assigned if the subject had a HEI-2015 total score ≥ median of study participants and 0 otherwise. For weight status, a value of 2 was assigned if the subject had normal weight, 1 if overweight or underweight, and 0 if obese. The total adherence score was the sum of all lifestyle factors, ranging from 0 (worst adherence) to 6 (best adherence).

HRQOL

HRQOL was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) version 2.18 The SF-36 comprises eight HRQOL domains that capture dimensions of health status or functioning in the past four weeks: physical functioning (limitations in physical activities), role limitations physical (limitations in daily activities due to physical problems), bodily pain (severity and interference), general health perceptions (general health status), vitality (energy and fatigue), social functioning (limitations in social activities), role limitations emotional (limitations in daily activities due to emotional problems), and mental health (psychological distress). Scores of the physical component summary scale (PCS) and mental component summary scale (MCS) were calculated. Scores of the individual domains, PCS, and MCS of each participant were standardized (mean=50 and a SD=10), adjusting for age and sex. Higher scores correspond to better HRQOL.

Statistical Analyses

Associations between lifestyle factors and HRQOL were examined using multivariable linear regression models. Results are reported as standardized beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI) that reflect the difference in HRQOL scores in association with adherence to lifestyle factors. Cohen’s effect size (ES) was estimated to determine the magnitude of HRQOL difference, with ES <2 points as negligible, 2.0–4.9 as small, 5.0–7.9 as medium, and ≥8.0 as large.19 Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, and treatment exposures. Treatment exposures were defined as radiation therapy (yes/no, overall and by mutually exclusive regions [head/neck only or head/neck + chest or head/neck + chest + abdomen/pelvis or chest +/− abdomen/pelvis]) and chemotherapy (yes/no, overall and by selected chemotherapy types which are not mutually exclusive). Directed acyclic graphs were used to identify a minimally sufficient set of covariates for each variable to reduce confounding bias and over-adjustment. Five lifestyle factors were adjusted in the same model to determine the potential independent associations of each factor with HRQOL. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Compared to nonparticipants, the 2,480 participants included in the study were similar in age, primary cancer diagnosis and age at diagnosis but were more likely to be female and non-Hispanic whites (Supplemental Table 2). Leukemia was the most common diagnosis among participants, followed by lymphoma, embryonal tumors, sarcoma, CNS tumors, and others (Table 1). The mean HEI-2015 total score was 60.1. Approximately one-half did not meet physical activity guidelines, two-thirds were overweight or obese, 23% were current smokers, and 10% consumed high amounts of alcohol. When adherence to all five lifestyle factors was evaluated, only 6.2% of the survivors achieved the maximum score of 6, and 50.5% had only half or less than half of the maximum score.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer in the St Jude Lifetime (SJLIFE) Cohort

| Characteristics | N (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Cancer and Treatment Exposure | |

| Cancer diagnosis, N (%) | |

| Leukemia | 952 (38.5) |

| Lymphoma | 488 (19.7) |

| Embryonal tumors | 324 (13.1) |

| Sarcoma | 311 (12.6) |

| Central nervous system tumors | 229 (9.3) |

| Other | 172 (7.0) |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 8.3 (5.6) |

| Time from diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 24.1 (8.1) |

| Radiation therapy, N (%) | |

| Radiation (any) | 1,487 (60.0) |

| Head/neck only | 664 (26.8) |

| Head/neck + chest | 158 (6.4) |

| Head/neck + chest + abdomen/pelvis | 442 (17.8) |

| Chest +/− abdomen/pelvis | 172 (6.9) |

| Chemotherapy, N (%) | |

| Alkylating agents | 1,567 (63.2) |

| Anthracyclines | 1,444 (58.2) |

| Antimetabolites | 1,320 (53.2) |

| Glucocorticoids | 1,226 (49.4) |

| Demographics | |

| Age at study enrollment, years, mean (SD) | 32.3 (8.3) |

| Sex, N (%) | 1,275 (51.4) |

| Men | 1,205 (48.6) |

| Women | |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2,076 (83.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 321 (12.9) |

| Other | 83 (3.3) |

| Education, N (%) | |

| Grades 0–12 | 665 (28.3) |

| Some post high school | 781 (33.2) |

| College graduate | 905 (38.5) |

| Marital status, N (%) | |

| Married | 1,006 (40.6) |

| Other | 1,474 (59.4) |

| Lifestyle Factors | |

| Health Eating Index-2015, mean (SD) | 60.1 (10.9) |

| Physical activity*, N (%) | |

| Active | 1,241 (50.5) |

| Inactive | 1,215 (49.5) |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.5 (7.4) |

| Weight status, N (%) | |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 84 (3.4) |

| Normal weight (BMI =18.5–24.9) | 807 (32.8) |

| Overweight (BMI =25–29.9) | 704 (28.6) |

| Obese (BMI ≥30) | 868 (35.2) |

| Smoking, N (%) | |

| Nonsmokers | 1,621 (65.6) |

| Former smokers | 284 (11.5) |

| Current smokers | 565 (22.9) |

| Alcohol, drink/week, N(%) | |

| Nondrinkers | 1,176 (47.9) |

| Moderate | 1,038 (42.3) |

| High | 239 (9.7) |

| Adherence scores to healthy lifestyle behaviors, N(%) | |

| 0–2 | 568 (22.9) |

| 3 | 685 (27.6) |

| 4 | 651 (26.3) |

| 5 | 423 (17.1) |

| 6 | 153 (6.2) |

Minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) were calculated by summarizing minutes, with vigorous physical activities weighted at 1.67 minutes for each minute of vigorous physical activity. Participants were classified as physically active if MVPA met or exceeded 150 minutes per week, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.15

Moderate alcohol intake was defined as ≤ 1 drink/day for women and ≤ 2 drinks/day for men; and high alcohol intake was defined as > 1 drink/day for women and >2 drinks/day for men, according to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.16

Survivors who were physically active had higher HRQOL in both physical and mental health domains (PCS β=3.10, p<0.0001; MCS β=1.48, p=0.002) than those inactive, and obese survivors had lower HRQOL in both physical and mental health domains (PCS β= −3.29, p<0.0001; MCS β= −1.61, p=0.005) compared to those with a normal weight (Table 2). Survivors with the highest quartile of diet quality (HEI-2015), compared to those in the lowest quartile, reported higher HRQOL in the physical (PCS β=1.79, p=0.003) but not mental health domain. Compared to nonsmokers, current smokers had lower HRQOL in both physical and mental health domains (PCS β= −2.30, p<0.0001; MCS (β= −6.49, p<0.0001) whereas being a former smoker was associated with lower HRQOL only in the mental health domain (MCS β= −1.69, p=0.02). Compared to nondrinkers, survivors who had moderate alcohol intake had higher HRQOL in the physical health domain (PCS β=1.14, p=0.006) and lower HRQOL in the mental health domain (MCS β= −1.13, p=0.02).

Table 2.

Lifestyle Factors and Physical/Mental Component Summary (PCS/MCS) HRQOL in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer*

| Physical Component Summary (PCS) | Mental Components Summary (MCS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| beta | P | beta | P | |

| Age, years (ref: 18–29) | ||||

| 30–39 | −2.14 | <.0001 | −0.99 | .05 |

| ≥40 | −6.19 | <.0001 | −0.07 | .91 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.71 | .09 | 2.29 | <.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: non-Hispanic White) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black and other | −0.58 | .30 | 0.04 | .95 |

| Education (ref: Grades 0–12) | ||||

| Post high school/some college | 3.69 | <.0001 | 2.48 | <.0001 |

| College graduate | 5.76 | <.0001 | 3.58 | <.0001 |

| Marital status (married vs. other) | 1.74 | .0003 | 2.78 | <.0001 |

| Radiation therapy (ref: no RT) | ||||

| Any RT | −2.16 | <.0001 | −0.42 | .39 |

| Head/neck only | −1.71 | .001 | −0.59 | .33 |

| Head/neck + chest | −1.76 | .05 | −1.82 | .08 |

| Head/neck + chest + abdomen/pelvis | −3.30 | <.0001 | 0.05 | .96 |

| Chest +/− abdomen/pelvis | −2.74 | 0.002 | −0.12 | .90 |

| Chemotherapy (ref: no chemotherapy) | ||||

| Alkylating agents | −1.71 | <.0001 | −0.08 | .87 |

| Anthracyclines | 0.45 | .35 | −0.23 | .69 |

| Antimetabolites | −0.26 | .71 | 0.19 | .81 |

| Glucocorticoids | 0.41 | .57 | −0.34 | .66 |

| HEI-2015 (ref. Q1 <52.1) | ||||

| Q2 (52.2–60.0) | 0.50 | .35 | 0.72 | .26 |

| Q3 (60.1–67.8) | 1.84 | .001 | 1.20 | .07 |

| Q4 (≥67.9) | 1.79 | .003 | 1.31 | .06 |

| Physical Activity (active vs. inactive) | 3.10 | <.0001 | 1.48 | .002 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (ref: 18.5–24) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | −0.22 | .84 | 0.66 | .61 |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | −0.40 | .43 | −0.34 | .56 |

| Obese (≥30) | −3.29 | <.0001 | −1.61 | .005 |

| Smoking (ref: Nonsmokers) | ||||

| Former | −1.13 | .07 | −1.69 | .02 |

| Current | −2.30 | <.0001 | −6.49 | <.0001 |

| Alcohol, drink/week (ref: Nondrinkers) | ||||

| Moderate | 1.14 | .006 | −1.13 | .02 |

| High | 0.11 | .87 | 0.12 | .88 |

|

Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Factors (ref: adherence score <=2) |

||||

| 3 | 2.32 | <.0001 | 2.16 | 0.0004 |

| 4 | 4.96 | <.0001 | 4.32 | <.0001 |

| 5 | 5.78 | <.0001 | 5.03 | <.0001 |

| 6 | 7.69 | <.0001 | 5.76 | <.0001 |

| P trend<0.0001 | P trend<0.0001 | |||

Betas and P values for education and marital status were adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity; betas and P values for treatment were adjusted for age, sex, and cancer type; betas and P values for Healthy Eating Index-2015, physical activity, body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, lifestyle behaviors were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and five lifestyle factors (Healthy Eating Index-2015, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption) simultaneously in the same model; and betas and P values for adherence to healthy lifestyle factors were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Betas were standardized estimates that reflect T-scores (mean=50; SD=10) in each HRQOL domain in association with each risk factor.

Greater adherence to multiple lifestyle factors showed a linear trend with higher scores for both physical and mental health domains of HRQOL (Table 2). Compared to those with poor adherence (total adherence score ≤2), survivors with the best adherence (total adherence score=6) had more than ½ of the SD (SD=10) higher HRQOL scores (i.e., clinically significant impact) in both physical and mental health domains (PCS β= 7.69, p<0.0001; MCS β=5.75, p<0.0001).

In multivariable models adjusting for all five lifestyle factors, being physically active was associated with better HRQOL in each domain whereas obesity and current smoking were associated with lower HRQOL in each domain (Table 3). Having a high-quality diet was associated with better HRQOL in physical functioning, bodily pain, social functioning, and vitality. Moderate alcohol intake was associated with low mental health but high physical functioning and low role limitation physical. Adherence to multiple lifestyle factors was associated with each HRQOL domain in a dose-response fashion.

Table 3.

Lifestyle Factors and Eight Domains of HRQOL in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer*

| Physical Health Domain | Mental Health Domain | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Physical Functioning | Role Limitations due to Physical Problems | Bodily Pain | General Health Perceptions | Mental Health | Role Limitations due to Emotional Problems | Social Functioning | Vitality | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

|

HEI-2010 (ref: Q1 <52.1) |

||||||||||||||||

| Q2 (52.2–60.0) | 0.62 | .26 | 0.34 | .56 | 0.99 | .09 | 1.17 | .06 | 0.32 | .60 | 0.87 | .16 | 1.02 | 0.08 | 0.89 | .14 |

| Q3 (60.1–67.8) | 1.71 | .003 | 0.29 | .63 | 2.35 | .0001 | 2.23 | .001 | 1.31 | .04 | 1.48 | .02 | 1.39 | 0.02 | 1.63 | .01 |

| Q4 (≥67.9) | 2.14 | .0004 | 0.76 | .23 | 2.02 | .002 | 2.15 | .002 | 1.32 | .05 | 1.16 | .09 | 1.59 | 0.01 | 2.11 | .001 |

| Physical Activity | ||||||||||||||||

| Active vs. inactive | 3.46 | <.0001 | 2.63 | <.0001 | 1.53 | .0004 | 3.26 | <.0001 | 2.71 | .01 | 2.39 | <.0001 | 2.04 | <.0001 | 2.76 | <.0001 |

|

Body Mass Index, kg/m2 (ref: 18.5–24.9) |

||||||||||||||||

| <18.5 | 0.40 | .73 | 0.53 | .66 | 1.34 | 0.27 | −2.60 | .045 | −0.06 | .96 | 1.43 | .27 | 2.22 | .07 | −0.52 | .67 |

| 25–29.9 | −0.75 | .14 | 0.03 | .95 | −0.15 | 0.78 | −1.14 | .048 | −0.61 | .28 | −0.35 | .54 | −0.50 | .36 | −0.53 | .34 |

| ≥30 | −3.15 | <.0001 | −1.74 | .001 | −3.05 | <.0001 | −4.14 | <.0001 | −2.61 | <.0001 | −1.36 | .01 | −2.07 | <.0001 | −2.76 | <.0001 |

|

Smoking (ref: Nonsmokers) |

||||||||||||||||

| Former | −0.67 | .28 | −0.86 | 0.65 | −2.71 | <.0001 | −1.82 | .01 | −1.96 | .005 | −1.60 | 0.02 | −1.48 | 0.03 | −1.31 | .05 |

| Current | −2.58 | <.0001 | −3.03 | <.0001 | −4.73 | <.0001 | −4.60 | <.0001 | −6.25 | <.0001 | −5.67 | <.0001 | −5.04 | <.0001 | −4.39 | <.0001 |

|

Alcohol, drink/wk (ref: Nondrinkers) |

||||||||||||||||

| Moderate | 1.03 | .01 | 1.11 | .01 | −0.14 | .75 | .20 | .68 | −1.21 | .01 | −0.27 | .54 | −0.07 | .87 | −0.43 | .35 |

| High | −0.09 | .90 | 0.69 | .35 | −0.75 | .32 | .05 | .95 | −0.40 | .61 | −0.29 | .73 | 0.65 | .39 | 0.43 | .57 |

|

Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle (ref: score ≤2) |

||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 2.35 | <.0001 | 2.58 | <.0001 | 2.11 | 0.001 | 3.28 | <.0001 | 2.57 | <.0001 | 2.52 | <.0001 | 1.95 | <.0001 | 2.42 | <.0001 |

| 4 | 4.99 | <.0001 | 3.99 | <.0001 | 4.84 | .0004 | 6.05 | .0004 | 4.56 | <.0001 | 4.85 | <.0001 | 4.34 | .001 | 4.73 | <.0001 |

| 5 | 5.98 | <.0001 | 4.37 | <.0001 | 5.88 | <.0001 | 7.54 | <.0001 | 5.57 | <.0001 | 5.51 | <.0001 | 5.14 | <.0001 | 5.34 | <.0001 |

| 6 | 7.81 | <.0001 | 4.93 | <.0001 | 7.05 | <.0001 | 10.20 | <.0001 | 6.38 | <.0001 | 5.70 | <.0001 | 5.71 | <.0001 | 8.52 | <.0001 |

Betas and P-values for HEI-2010, physical activity, BMI, smoking and alcohol, models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and five lifestyle factors simultaneously. Betas and P-values for adherence to healthy lifestyle, models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, radiation therapy (yes/no for the following mutually exclusive categories: head/neck only, head/neck + chest, head/neck + chest + abdomen/pelvis, chest +/− abdomen/pelvis without head/neck), and chemotherapy (yes/no for alkylating agents, anthracyclines, antimetabolites, and glucocorticoids). Betas were standardized estimates that reflect T-scores in each HRQOL domain in association with lifestyle factors.

DISCUSSION

In a large cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer, we found modifiable lifestyle factors inclusive of diet, physical activity, body mass index, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption were significantly associated with HRQOL. Increased adherence to multiple healthy lifestyle factors demonstrated a linear increase in both physical and mental domains of HRQOL. Our findings identified important intervention targets for childhood cancer survivors that may positively impact both of their mental health and functional status.

Long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for treatment-related chronic health conditions20 and/or symptoms of health complications,21 which can negatively impact HRQOL. Yeh et al reported lower quality of life in 7,105 adult survivors of childhood cancer survivors compared to the general population.20 Lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity are modifiable behaviors that have established effects on HRQOL in the general population.22, 23 We found a clear trend of adherence to multiple lifestyle factors associated with better HRQOL in all eight domains. It is important to note that adherence to multiple healthy lifestyle factors (e.g., 3–5 healthy lifestyle factors) were associated with at least half of the standard deviation increase in HRQOL. While this represents a clinically meaningful difference,19, 24 our results also imply that cancer survivors need to be advised to adopt multiple health behaviors to achieve clinically meaning improvement in HRQOL.

Importantly, these modifiable lifestyle factors showed comparable magnitude of associations with HRQOL to that of demographic and treatment factors that are not amenable to interventions.21 For example, the negative impact of radiation therapy or alkylating agents on the physical domain of HRQOL ranged from −1.7 to −3.3, similar to the magnitude of the association between individual lifestyle factors and HRQOL (obesity: −3.3; current smoking: −2.3; being physically active: 3.1; better diet quality: 1.8). Thus, the significant impact of these treatment exposures on HRQOL was similar to the impact from adherence to multiple lifestyle factors. Because childhood cancer survivors receive cancer treatment at a young age, they are likely to experience treatment-related complications for longer periods of time and during critical stages of development of behavioral patterns.25 Thus, it is important to consider lifestyle interventions early to improve the long-term health of the growing population of childhood cancer survivors.

Among the five lifestyle factors evaluated in our study, meeting physical activity guidelines had the strongest association with high physical HRQOL and being obese had the strongest association with low physical HRQOL. Current smoking had the strongest association with low mental HRQOL. Eating a healthy diet had a stronger association with physical than mental HRQOL. Interestingly, moderate alcohol consumption was associated with high physical but low mental HRQOL. This bidirectional association of HRQOL with alcohol consumption has been previously reported in 92,448 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study. 26 Although moderate alcohol consumption has recognized benefits on heart health, a recent meta-analysis provided strong evidence that pre- and post-diagnosis alcohol consumption was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality and cancer recurrence among cancer survivors.27 The underlying mechanisms for the bidirectional association between alcohol consumption and HRQOL among cancer survivors remain to be defined in future studies.

Childhood cancer survivors who had the best adherence to modifiable lifestyle factors reported the highest HRQOL in two physical health (physical functioning and general health perceptions) and one mental health domains (vitality). A prior study of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer also noted that greater fatigue was associated with dietary intake including a higher percent of energy from fat, and that greater fatigue and lower physical functioning was associated with not meeting physical activity recommendations.7 Another study reported higher physical functioning, but not social functioning, cognitive functioning, or pain, was associated with higher levels of physical activity among adult survivors of childhood cancer.10 These findings may suggest that among multiple HRQOL domains, physical functioning and fatigue are ones most strongly associated with lifestyle factors. Advising childhood cancer survivors to follow a healthy lifestyle can particularly improve survivors’ physical functioning and vitality.

This study’s strengths include characterization of HRQOL in a large cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer with different cancer diagnoses, and the use of valid and reliable measures of lifestyle factors. The availability of demographic and treatment data allowed multivariable adjustments and comparisons of the magnitude of the associations. We chose not to adjust for comorbidities given that comorbidities are strongly associated with the cancer treatments and operate as intermediates on the pathway from lifestyle factors to HRQOL.28 Study limitations include measurement errors associated with self-reported lifestyle factors and social desirability of reporting a healthy lifestyle. Such misreporting could result in attenuation of the true magnitude of the observed associations. Cross-sectional nature of our study precludes making causal inference between lifestyle factors and HRQOL, particularly since the recall period for the various lifestyle factors differ. Because we evaluated five lifestyle factors in the same study, some of the results could potentially be due to false positive findings. Our results may be subject to selection bias from non-participation. However, an analysis of the overall SJLIFE cohort suggested no substantial differences in demographic, disease, and neighborhood characteristics between participants and non-participants, thus alleviating serious concerns about selective non-participation in the cohort.29

Despite these limitations, our study provides one of the first evaluations of the impact of lifestyle factors on HRQOL in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Our findings underscore the potential for optimizing survivors’ HRQOL by increasing adherence to healthy lifestyle factors. Future research is needed to identify barriers to adhering to a healthy lifestyle, and to evaluate the cost and effectiveness of integrating health promoting lifestyle interventions into cancer care for this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This study was supported by NIH/NCI 1R03CA199516-01 (FFZ), NIH/NCI U01CA194457 (MMH/LLR), and by ALSAC. The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of this study or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest (COI) Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Author Contributions: FZ, KK, MH and IH designed this research; FZ, LL, and FC performed statistical analysis; FZ wrote the original draft; KK, MH, IH, NB, KN, TB, JK, RO, JL and LL critically reviewed and revised the paper; FZ had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:435–446. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang FF, Ojha RP, Krull KR, et al. Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer Have Poor Adherence to Dietary Guidelines. J Nutr. 2016;146:2497–2505. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.238261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florin TA, Fryer GE, Miyoshi T, et al. Physical inactivity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1356–1363. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosher CE, Sloane R, Morey MC, et al. Associations between lifestyle factors and quality of life among older long-term breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:4001–4009. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badr H, Chandra J, Paxton RJ, et al. Health-related quality of life, lifestyle behaviors, and intervention preferences of survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:523–534. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellano C, Perez-Campdepadros M, Capdevila L, Sanchez de Toledo J, Gallego S, Blasco T. Surviving childhood cancer: relationship between exercise and coping on quality of life. Span J Psychol. 2013;16:E1. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2013.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murnane A, Gough K, Thompson K, Holland L, Conyers R. Adolescents and young adult cancer survivors: exercise habits, quality of life and physical activity preferences. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:501–510. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paxton RJ, Jones LW, Rosoff PM, Bonner M, Ater JL, Demark-Wahnefried W. Associations between leisure-time physical activity and health-related quality of life among adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancers. Psychooncology. 2010;19:997–1003. doi: 10.1002/pon.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, et al. Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:825–836. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires : the Eating at America’s Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1089–1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute. Comparing the HEI-2015, HEI-2010 & HEI-2005. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:243–274. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waren JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to scroe version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2136–2145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh JM, Hanmer J, Ward ZJ, et al. Chronic Conditions and Utility-Based Health-Related Quality of Life in Adult Childhood Cancer Survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016:108. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang IC, Brinkman TM, Kenzik K, et al. Association between the prevalence of symptoms and health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4242–4251. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.8867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carson TL, Hidalgo B, Ard JD, Affuso O. Dietary interventions and quality of life: a systematic review of the literature. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:401–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang FF, Parsons SK. Obesity in Childhood Cancer Survivors: Call for Early Weight Management. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:611–619. doi: 10.3945/an.115.008946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schrieks IC, Wei MY, Rimm EB, et al. Bidirectional associations between alcohol consumption and health-related quality of life amongst young and middle-aged women. J Intern Med. 2016;279:376–387. doi: 10.1111/joim.12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwedhelm C, Boeing H, Hoffmann G, Aleksandrova K, Schwingshackl L. Effect of diet on mortality and cancer recurrence among cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Rev. 2016;74:737–748. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE) Lancet. 2017;390:2569–2582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31610-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ojha RP, Oancea SC, Ness KK, et al. Assessment of potential bias from non-participation in a dynamic clinical cohort of long-term childhood cancer survivors: results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:856–864. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.