Highlights

-

•

Exercise training is beneficial to cardiovascular system

-

•

MicroRNAs are responsible for cardiac adaptions to exercise

-

•

Exercise regulated microRNAs benefits heart

-

•

MicroRNAs mediate protective effects of exercise in cardiovascular diseases

-

•

Circulating microRNAs mediate beneficial effects of exercise

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, Circulating microRNAs, Exercise, MicroRNAs

Abstract

Exercise training is beneficial to the cardiovascular system. MicroRNAs (miRNAs, miRs) are a class of conserved non-coding RNAs and play a wide-ranging role in the regulation of eukaryotic gene expression. Exercise training alters the expression levels of large amounts of miRNAs in the heart. In addition, circulating miRNAs appear to be regulated by exercise training. In this review, we will summarize recent advances in the regulation of miRNAs during physical exercise intervention in various cardiovascular diseases, including pathologic cardiac hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. The regulatory role of circulating miRNAs after exercise training was also reviewed. In conclusion, miRNAs might be a valuable target for treatment of cardiovascular diseases and have great potential as biomarkers for assessment of physical performance.

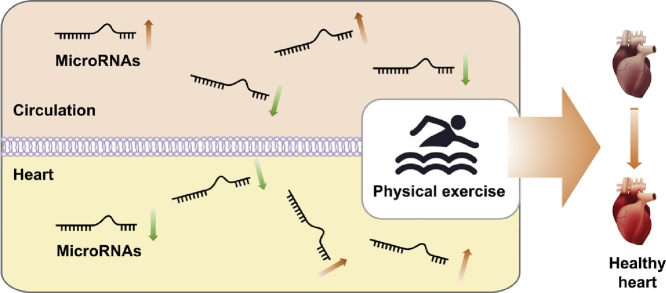

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Exercise can effectively reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. Although the precise molecular mechanism of the beneficial effects of exercise remains unclear, a number of studies have shown that physical exercise can restore myocardial function; improve maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max); and improve endothelial cell function, left ventricular systolic function, and diastolic function.1 Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is effective at all stages of cardiovascular disease treatment and has an important protective effect on cardiovascular disease.2, 3, 4 Therefore, exercise has been used as a non-pharmacologic supplement to support traditional treatment and prevent cardiovascular disease.1, 5 In this review, we review the regulatory role of microRNAs (miRNAs, miRs) in the heart during physical exercise. Attention will be paid to understanding the current knowledge of (1) cardiac adaptations in response to exercise, (2) miRNAs in the heart, and (3) the adaptation of circulating miRNAs (c-miRNAs) to exercise. Finally, the implications and future prospects of miRNAs in heart and circulation will be discussed.

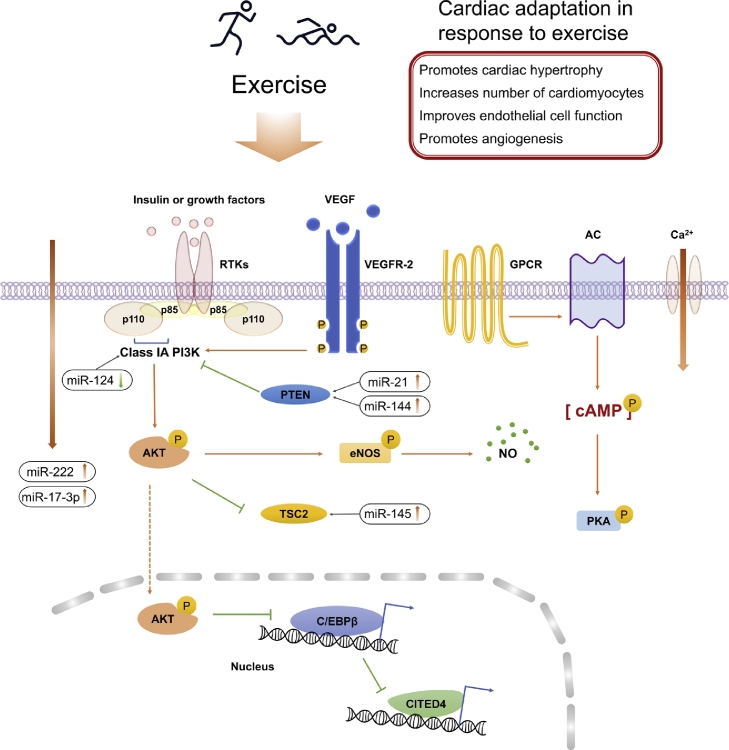

2. Cardiac adaptation in response to exercise

Exercise training can make the heart adapt to changes in morphology, structure, and function (Fig. 1). Long-term exercise training can induce cardiac physiological growth, which is characterized by increased formation of new cardiomyocytes and cardiomyocytes size. Exercised hearts in animals have been found to have a significantly increased number of new cardiomyocytes.6 Using multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry, researchers have found an elevated number of newly generated cardiomyocytes after exercise.7 It has been found that injection of 5-fluorouracil inhibits cardiac cell proliferation and limits the exercised-induced cardioprotective effects from ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury without affecting the exercised-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo.8

Fig. 1.

Cardiac adaptations in response to exercise. The adaptations of the heart to exercise include changes in morphology (physiological hypertrophy), structure (angiogenesis), and function (improved vascular endothelial function and increased number of cardiomyocytes). AC = adenylyl cyclase; AKT = serine/threonine kinase; cAMP = cyclic adenosine monophosphate; C/EBPβ = CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β; CITED4 = Cbp/p300 interacting transactivator with Glu/Asp rich carboxy-terminal domain 4; eNOS = endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GPCR = G protein-coupled receptor; NO = nitric oxide; PKA = cAMP-dependent protein kinase A; PI3K = phosphoinositide-3-kinase; RTK = receptor tyrosine kinase; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

The IGF-1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is key in regulating cardiac physiological growth.9, 10, 11, 12 Insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) are activators of AKT in cardiomyocytes, and IGF signaling regulates normal growth of embryonic and postnatal organs. High expression of IGF-1 was found in athletes’ myocardium accompanied by physiological cardiac hypertrophy.13 On binding of IGF-1 to the tyrosine kinase receptor on the cell membrane, it activates the activity of p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K and AKT1. The p110α knockout mice are lethal, and physiological cardiac hypertrophy can be induced by IGF-1 or long-term high-intensity exercise to activate p110α.12, 14 Conversely, inhibition of p110α protein expression by p110α dominant negative mutation can impair myocardial normal growth and block exercise-induced physiological cardiac hypertrophy. The simultaneous loss of p85α and p85β in the myocardium also leads to a decrease in myocardial growth.15

Increased AKT1 in cardiomyocytes also leads to a decrease of the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ). C/EBPβ is one of the members of the bHLH family of transcription factors, and its main function is to regulate cell proliferation and transcription of differentiated genes. In the development of physiological cardiac hypertrophy, the expression of the C/EBPβ gene is down-regulated, and CITED4 is up-regulated.16 Silencing of C/EBPβ by small interfering RNA (SiRNA) can promote cardiomyocytes proliferation, confirming that physiological cardiac hypertrophy can be down-regulated by C/EBPβ and mediated by CITED4. This suggests that the induced cell proliferation caused by down-regulation of C/EBPβ expression may be mediated by the negative regulation of CITED4. In addition, C/EBPβ down-regulation in zebrafish embryos can effectively induce cardiomyocyte proliferation; a clear increased proliferation of cardiomyocytes in C/EBPβ heterozygous mice has also been observed. Lower C/EBPβ levels in mice have been found to be effective against heart dysfunction in transverse aortic constriction–induced pressure overload.16 CITED4 negatively regulates cardiomyocytes elongation caused by eccentric hypertrophy, which is highly associated with cardiac dysfunction.17 Overexpression of CITED4 activates mTORC1 pathways and promotes cardiac functional recovery from I/R injury.18 These reports suggest that C/EBPβ/CITED4 regulates the hypertrophy and proliferation of cardiomyocytes in mammalian hearts caused by physiological stimuli.

In addition to cardiac growth, endothelial nitric oxide synthases/NO is up-regulated and regulates vascular homeostasis during exercise training.19 Exercise also induces angiogenesis via increasing the expression level of vascular endothelial growth factor and promoting PI3K/AKT signaling.20, 21 In addition, exercise regulates the action potential and excitation-contraction coupling (E-C coupling) through stimulation of G protein-cAMP-PKA signaling pathways and Ca2+ uptake.22

3. The benefits of miRNAs and exercise-regulated miRNAs to the heart

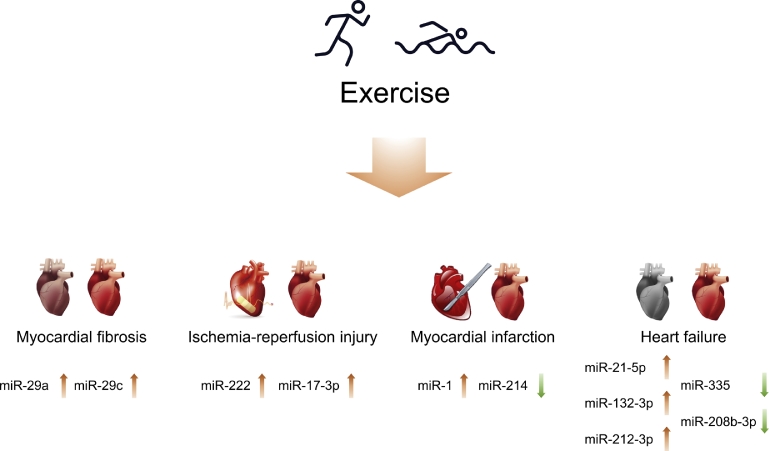

The miRNAs are a class of highly conserved non-coding RNAs whose mature sequences often consist of 18–25 nucleotides. MiRNAs regulate the expression of specific target genes by binding to complementary sequences in mRNA to induce degradation of mRNA or to inhibit translation of proteins.23 The maturation process of miRNAs is controlled by multiple post-transcriptional regulatory steps. Similar to mRNA, primary miRNAs are mainly produced by direct transcription under the action of RNA polymerase II. These primary miRNA transcripts are further cleaved by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex and folded into precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) of 70–110 nucleotides.24 Generally, the pre-miRNA is transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. After being released into the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNA is cleaved by DICER into a short-chain mature miRNA. The mature miRNA is then loaded into the RISC/Argonaut complex, which recognizes and binds to and cleaves the sequence that the 3′-UTR of the mRNA specifically binds to the miRNA.25 Ultimately, the stability of the mRNA is decreased or the protein translation process is directly inhibited. Numerous miRNAs in the heart are altered after exercised training.26 The modulation of miRNAs in exercise-induced cardioprotection has received increasing attention.27, 28 In the following sections, we will briefly summarize the role that miRNAs involved in exercise play in protecting against cardiovascular diseases (Fig. 2) and will describe the role of several miRNAs that have been examined in detail (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Exercise-regulated microRNAs that benefit the heart. MicroRNAs mediate the protective effects of exercise in cardiovascular diseases including myocardial fibrosis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, myocardial infarction, and heart failure.

Table 1.

Summary of well-studied miRNAs involved in exercise protecting against cardiovascular diseases.

| Related diseases | Exercise type | miRNAs | Targets | Regulation | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial fibrosis | Swimming | miR-29a miR-29c | Col1a1, Col3a1 | ↑ | Antifibrotic | 32 |

| Col1a1, Col3a1 | ↑ | Pro-hypertrophy | ||||

| Myocardial I/R injury | Running/swimming | miR-222 | p27, HIPK1, HMBOX1 | ↑ | Increase cardiac growth | 36 |

| Myocardial I/R injury | Running/swimming | miR-17-3p | TIMP3 | ↑ | Increase cardiac growth | 38 |

| Myocardial infarction | Swimming | miR-1 | NCX-1 | ↑ | Anti-angiogenesis | 42 |

| miR-214 | SERCA-2 | ↓ |

Abbreviations: Col1a1 = collagen alpha-1(I) chain; Col3a1 = collagen alpha-1(III) chain; HIPK1 = homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1; HMBOX1 = homeobox-containing protein 1; I/R = ischemia-reperfusion; miRNAs = microRNAs; NCX-1 = sodium/calcium exchanger-1; p27 = cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B; SERCA-2 = sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2; TIMP3 = metalloproteinase inhibitor 3.

3.1. MiRNAs mediate protective effects of exercise in myocardial fibrosis

Myocardial fibrosis is characterized by excessive proliferation of cardiac fibroblast and collagen deposition.29 The occurrence of cardiac fibrosis is closely related to various cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction (MI), hypertension, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiac fibrosis is a common pathologic change in the development of a variety of heart diseases and is also an important cause of ventricular remodeling. The main manifestations of cardiac fibrosis in the pathologic morphology are increased collagen deposition and the imbalance of various types of collagen, especially the disproportion of type I and type III collagen, accompanied by proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts.30 The miR-29 family is involved in the regulation of the fibrotic processes of various diseases. In the heart, miR-29 targets a variety of matrix proteins to regulate their expression. MiR-29 was found to be dramatically down-regulated in cardiac fibrotic scar after MI.31 Up-regulation miR-29 could reduce total collagen content. After a microarray analysis in 2 different protocols of swimming training was conducted, 87 miRNAs among 349 different miRNAs were found to be significantly altered.32 In the miR-29 family, miR-29a and miR-29c were both up-regulated after swimming training; correspondingly, col1a1 and col3a1, target genes of miR-29a and miR-29c, decreased in both training groups.32

3.2. miRNAs mediate protective effects of exercise in I/R injury

After partial or complete acute obstruction of the coronary artery, the ischemic myocardium can resume normal perfusion when it is re-established, but its tissue damage is a pathologic process of progressive aggravation. When the ischemic tissue restores blood perfusion, it leads to significant pathophysiological changes in the myocardium and the local vascular network in the reperfusion area, as well as a series of damaging changes caused by ischemia. These changes work together to promote further tissue damage, a phenomenon known as myocardial I/R injury.33 I/R injury will greatly reduce the efficacy of myocardial reperfusion. Its mechanism is currently thought to be mainly related to the large amount of intracellular oxygen-free radicals, calcium ion overload, inflammatory effects of white blood cells, and high-energy phosphate compounds.34, 35 Because of the high incidence and high mortality of I/R injury, the mechanism and treatment of such diseases have received extensive attention. MiRNAs and exercise protection from I/R injury have also been studied in relation to myocardial I/R injury.

MiR-222 is the first miRNA to be fully studied in relation to exercise and the prevention of myocardial I/R injury.36 MiR-222 resides in close proximity to the X chromosome and constitutes a miR-222∼221 cluster. A microarray analysis found that miR-222 was elevated in mice that participated in both wheel running and swimming exercise models. Interestingly, it has been reported that miR-222 was also elevated in the peripheral blood of young athletes.37 In addition, elevated levels of miR-222 were found in circulating blood of 28 exercise-trained patients with heart failure. Overexpression of miR-222 promotes cardiomyocytes growth and proliferation in vitro and in vivo through targeting p27, HIPK1, and HMBOX1. Inhibition of miR-222 in vivo prevented exercise-induced cardiac growth. The use of cardiac-specific miR-222 transgenic mice to study the miR-222 in vivo effects demonstrated that overexpression of miR-222 protects against cardiac I/R injury.36 Another miRNA, miR-17-3p, was also found at increased levels in 2 different murine exercise models.38 Similar to miR-222, the miR-17-3p expression level was found to be heightened in serum from exercise-trained patients with chronic heart failure. MiR-17-3p promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and increased cardiomyocyte size through directly targeting TIMP3 and indirectly regulating the PTEN-AKT signal pathway. In vivo, miR-17-3p inhibition could lessen the exercise-induced cardiac growth. Overexpression of miR-17-3p could protect against I/R injury-induced cardiac remodeling.38 Interestingly, TIMP3 was also identified as the target gene of miR-222 in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.39 However, it remains to be studied whether TIMP3 in cardiomyocytes acts as a target gene of miR-222 as it mediates the protective effect on the heart.

3.3. MiRNAs mediate protective effects of exercise in MI

MI is an ischemic death of the myocardium. In coronary artery disease, the blood flow of the coronary artery is drastically reduced, causing severe and long-lasting acute ischemia of myocardium, eventually leading to ischemic death of the myocardium.40 In the ischemic heart, mitochondrial structure and function are damaged, oxidative phosphorylation is impaired, adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) production is insufficient, and the calcium pump is dysfunctional. Therefore, when calcium is overloaded, excessive Ca2+ in the cytoplasm cannot be excreted outside the cell, causing the Ca2+ concentration in the cytoplasm to further increase, activating various cellular pathways and leading to myocardial cell death. It is generally believed that the ratio of Na+ concentration inside and outside the cell is closely related to the transport and overload of Ca2+. In the presence of myocardial ischemia, the expression of the sodium/calcium exchanger, sarcoplasmatic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA-2), and phospholamban was decreased. Aerobic intensity–controlled, interval training–increased cardiomyoyte function after MI was accompanied by elevated SERCA-2 protein expression and Ca2+-sensitivity.41 MI leads to decreased expression of miR-1 and increased expression of miR-214; sodium/calcium exchanger and SERCA-2 are targeted by miR-1 and miR-214 in the remote region of myocardium. It has been reported that exercise training can prevent the decrease of miR-1 expression and the increase of miR-214 expression induced by MI, which in turn promotes cardiac recovery of Ca2+ handling.42

3.4. MiRNAs mediate protective effects of exercise in heart failure

Heart failure is not an independent disease but the end stage of heart disease development. Almost all cardiovascular diseases, such as MI, cardiomyopathy, hemodynamic overload, inflammation, and other causes of myocardial damage, will eventually lead to heart failure.43 Although the significance of exercise training for the treatment of heart failure has been widely accepted, the mechanisms by which exercise training plays a protective role remain poorly understood. A number of studies have shown that long-term sedentariness can aggravate heart failure, and exercise training is beneficial for patients with heart failure.44, 45, 46 This phenomenon has also been verified in animal models of heart failure.47 In a study of the global changes in the expression of miRNAs in transverse aortic constriction–induced heart failure among rats before and after exercise training, 56 miRNAs were found to be abnormally regulated after exercise training, of which 38 were up-regulated and 18 were down-regulated.48 Among them, in previous studies involving I/R injury and cardioprotection by ischemic pre- and post-conditioning miR-21, miR-144, miR-146b, miR-208b, miR-212, miR-214, and miR-335 were also found to be dysregulated, which suggests that there may be some miRNAs that play a role in multiple cardioprotective intervention mechanisms, a possibility worthy of further study and discussion. Additional analysis of the expression of cardiac stress markers during heart failure showed that exercise training did not alter the expression levels of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and α-actin. Using miRTarBase, miRWalk, and further gene-term enrichment analysis, 26 pathways were clustered in 5 major biologic modules, including in programmed cell death, transforming growth factor-β signaling, cellular metabolic process, cytokine signaling, and cell morphogenesis.48

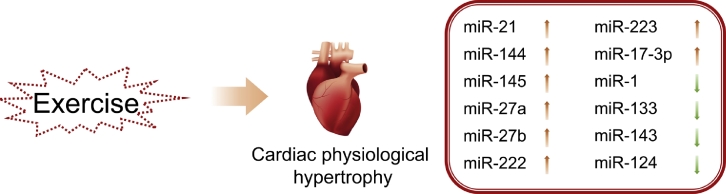

4. MiRNAs mediate exercise-induced cardiac physiological hypertrophy

The cardiac adaptations to exercise training include a set of beneficial effects on muscle metabolism, circulation system, and heart performance.49 Physiological cardiac hypertrophy is 1 phenotype induced by exercise training. The changes of many miRNAs are associated with physiological cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. 3). The expression of miR-1 and miR-133 is reduced in the hearts of rats after treadmill training.50 To evaluate the role of miRNAs in regulating the cardiac signal cascades in exercised rats, they were tested with swimming tasks. MiR-21 (target PTEN), miR-144 (target PTEN), and miR-145 (target TSC2) were up-regulated, whereas miR-124 (target PI3K) was down-regulated in the swimming training group,51 which was consistent with the model that exercise could induce left ventricular hypertrophy. Generally, the renin-angiotensin system of the heart increases when pathologic cardiac hypertrophy occurs, typically involving an increase in angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and angiotensin II (Ang II). In exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy, miR-27a and miR-27b (both target ACE) were significantly up-regulated, but miR-143 (target ACE2) was significantly down-regulated, which has been consistently associated with reduced expression levels of ACE and Ang II but elevated expression levels of ACE2 in animals trained with aerobic exercise.52 In treadmill-trained mice, the miR-223 in their hearts was up-regulated; this elevation of miR-223 could lead to physiological cardiac hypertrophy through directly targeting the 3′-UTRs of FBXW7 and Acvr2a.53 In addition to the expression of miR-222, miR-17-3p expression was also increased in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy.36, 38

Fig. 3.

MicroRNAs that mediate exercise-induced cardiac physiological hypertrophy.

5. Exercise-regulated circulating miRNAs are beneficial to the heart

In recent years, studies have shown that miRNAs can be released and exist outside the cell in a stable form to become c-miRNAs in plasma.54 The relative content of c-miRNAs under environmental stimulation and pathophysiological stress can be adaptively changed. It was also found that c-miRNAs have excellent stability in plasma and serum. Therefore, the potential value of c-miRNAs is indicated as possible biomarkers and physiological stress assessment indicators. In the past few years, various studies have focused on cardiovascular diseases and sought to develop sensitive and effective physiological indicators.55, 56, 57, 58 In the field of sports training, it is also necessary to develop new biomarkers to evaluate the adaptation to exercise.59 Therefore, certain characteristics of miRNAs, which have shown unique value in the diagnosis and prognosis of various tumors and cardiovascular diseases, have rapidly attracted widespread attention. A summary of the changes in several c-miRNAs in response to different kinds of exercise is described in the following and shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the c-miRNAs in response to exercise.

| Source | Participant | Exercise type | c-miRNAs | Regulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | Matched on gender | Marathon running | miR-21 | Positively correlated with the FINDRISC | 60 |

| 40–45 years | miR-210 | Positively correlated with CRP | |||

| miR-222 | Positively correlated with serum ASAT | ||||

| Plasma | Male | Marathon running | miR-1 | ↑(immediately after running) | 56, 64 |

| 40–50 years | miR-133a | ||||

| miR-499 | |||||

| miR-208a | |||||

| Plasma | Male | Marathon running | miR-133 | ↑(immediately after running) | 65 |

| 56.8 ± 5.2 years | miR-126 | ||||

| Plasma | Male | Cycling | miR-21 | ↑(acute test before sustained training) | 37 |

| 19.1 ± 0.6 years | miR-221 | ||||

| miR-146 | ↑(acute test after sustained training) | ||||

| miR-222 | |||||

| Plasma | Male | Rowing | miR-20a | ↑(90-day training) | 37 |

| 19.1 ± 0.6 years | |||||

| Serum | Male | Cycling | miR-486 | ↓(acute exercise) | 66 |

| 21.5 ± 4.5 years | miR-486 | ↓(4-week training) | |||

| Serum | Male | Basketball | miR-221 | ↓(post acute exercise) | 68 |

| 25.90 ± 4.95 years | miR-21 | ||||

| miR-146a | |||||

| miR-210 | |||||

| miR-208b | ↓(3-month exercise) | ||||

| miR-221 | ↑(3-month exercise) |

Abbreviations: ASAT = aspartate aminotransferase; c-miRNAs = circulating miRNAs; CRP = C-reactive protein; FINDRISC = Finnish Type 2 Diabetes Risk Score.

Recently, there have been several studies on the effects of acute and chronic exercise training on c-miRNAs in the blood.60 A population of 4631 people who successfully completed the VO2max exercise test was selected for c-miRNAs screening. Participants were assigned to one of 2 groups: those with high VO2max (HV) and those with lower VO2max (LV). Each group has 12 participants, who ranged in age from 40–45 years. Among the 720 candidate c-miRNAs, miR-210 and miR-222 were found to be significantly higher in the the LV group than in the HV group. Results also showed that miR-21 was significantly higher in the male LV group compared with males in the HV group. At the same time, it was found that miR-21 and miR-222 were significantly positively correlated with the Finnish Type 2 Diabetes Risk Score. Additionally, miR-21 and C-reactive protein and miR-210 and serum aspartate aminotransferase were also significantly positively correlated.60 MiRNAs microarray analyses were further conducted to screen for differences in c-miRNAs in populations with different cardiorespiratory levels, and researchers selected miR-21, miR-210, and miR-222 for follow-up validation studies. Interestingly, these 3 miRNAs have been initially studied in the physiological functions of the cardiovascular system.61, 62, 63

In a study investigating the effects of 1-time marathon running on c-miRNAs, it was found that the changes in miRNAs that regulate muscle function (miR-1, miR-133a, miR-499, and miR-208a), miR-126, which regulates blood vessel growth, and miR-146a, which regulates inflammatory response, were significantly increased after marathon running and returned to pre-run levels at different speeds within 24 h in 21 male runners.56 Consistent with those findings, a study examining changes in c-miRNAs before and after running a marathon found that miR-1, miR-133a, miR-206, and miR-499, as well as miR-208, which is abundantly expressed in muscle, increased significantly among 14 male runners immediately after the run.64 Except for miR-499 and miR-208b, which recovered after 24 h, other miRNAs did not recover to a normal level.64 Similary, both c-miR-133 and c-miR-126 levels significantly increased after running a marathon among a population of 50 to 60 year olds.65

In a study of young healthy men, after 90 days of sustained exercise training it was found that miR-146 and miR-222 levels were significantly elevated after acute exercise but were not affected by long-term training.37 MiR-21 and miR-221 significantly increased after acute exercise before long-term training but were not sensitive to acute exercise after long-term training, suggesting that long-term exercise training reduces the sensitivity of miR-21 and miR-221 to acute exercise. MiR-20a increased significantly after long-term training but was not sensitive to acute exercise. MiR-133a, miR-210, and miR-328 did not significantly respond to long-term exercise training and acute exercise.37 In a study of 11 healthy men involving the detection of circulating miR-1, miR-133, miR-206, miR-208b, miR-499, and miR-486 expression, it was found that c-miR-486 was significantly reduced after both acute exercise and 4 weeks of training.66 It is worth noting that miR-486 can promote PI3K/AKT signaling by inhibiting the target protein PTEN, which regulates insulin-dependent sugar transport and skeletal muscle energy metabolism.67 Therefore, the decrease of c-miR-486 during exercise may be the result of absorption by the muscles. This indicates that maintaining c-miR-486 levels may be important for exercise endurance. Circulating miRNA levels in response to acute exercise and 3 months of long-term basketball training were also detected in the basketball athletes.68 Among the participants, circulating miR-221 demonstrated different behaviors after acute exercise and long-term basketball training. The miR-221 level in serum decreased after acute exercise, whereas it increased after 3 months of basketball training. MiR-208b was not sensitive to acute exercise, but it decreased after long-term basketball training. Circulating miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-210 levels only decreased after acute exercise.68

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

Increasing evidence has demonstrated that miRNAs are important for cardiac protection in response to exercise training. However, the regulation mechanism of miRNAs in exercise beneficial to the heart is still relatively obscure, and only a small number of studies have investigated the details about the relationship between exercise that is beneficial to the heart and miRNA regulation.

In addition to miRNAs, the role of long non-coding RNAs and circular RNAs in exercise-induced cardioprotective effects remains unknown. Further studies should be undertaken to explore the underlying mechanisms responsible for cardiac adaptations to exercise and the regulation of non-coding RNAs.

Interestingly, in addition to playing an important role in exercise that is beneficial to the heart, miRNAs are also involved in the development or progression of some cardiovascular diseases. This suggests that studying the potential role of miRNAs in response to exercise could lead to a new drug for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases or to the discovery of new therapeutic strategies. However, differences between the human species and mouse species should be considered before therapeutic strategies are transitioned from the laboratory bench to the medical clinic.

For c-miRNAs, muscle-specific miRNAs are being studied more intensely, whereas non-muscle–specific forms are being studied less frequently. The exercise-sensitive, non-muscle–specific circulating miRNAs responsible for tissue development and physiological functions are not well understood. It is important to explore these c-miRNAs and their functions before developing them as physical performance biomarkers.

Last but not least, there has been great interest in exploring c-miRNAs in blood as potential biomarkers. The c-miRNAs may be released into blood through their association with lipid vesicles (exosomes, microvesicles, apoptotic bodies) or proteins, and they further mediate cell-to-cell communication. Lipid vesicles derived from different cells/tissues exhibit different secretion characteristics when used as a carrier of miRNAs. At the same time, different miRNAs also have different carrier selectivity when secreted into blood. The c-miRNAs can be absorbed by distant tissue cells along with blood flow, thereby regulating the metabolism of other tissues and organs and playing a role in information regulation between cells. However, whether and to what extent c-miRNAs can be released from specific tissues and exert paracrine function remains to be investigated. It is important to learn more about the role of c-miRNAs in intercellular communication.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81722008, 91639101, and 81570362 to JX and 81800358 to LW), the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2017-01-07-00-09-E00042 to JX), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (17010500100 to JX), and the development fund for Shanghai talents (to JX).

Authors’ contributions

LW and JX performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript; YL and GL draw the figures; JX edited and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

References

- 1.Wei X, Liu X, Rosenzweig A. What do we know about the cardiac benefits of exercise? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMullen JR, Amirahmadi F, Woodcock EA, Schinke-Braun M, Bouwman RD, Hewitt KA. Protective effects of exercise and phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110α) signaling in dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:612–617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606663104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenk K, Erbs S, Hollriegel R, Beck E, Linke A, Gielen S. Exercise training leads to a reduction of elevated myostatin levels in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:404–411. doi: 10.1177/1741826711402735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quindry J, French J, Hamilton K, Lee Y, Mehta JL, Powers S. Exercise training provides cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion induced apoptosis in young and old animals. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huh JY, Mougios V, Kabasakalis A, Fatouros I, Siopi A, Douroudos II. Exercise-induced irisin secretion is independent of age or fitness level and increased irisin may directly modulate muscle metabolism through AMPK activation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E2154–E2161. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waring CD, Vicinanza C, Papalamprou A, Smith AJ, Purushothaman S, Goldspink DF. The adult heart responds to increased workload with physiologic hypertrophy, cardiac stem cell activation, and new myocyte formation. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2722–2731. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vujic A, Lerchenmuller C, Wu TD, Guillermier C, Rabolli CP, Gonzalez E. Exercise induces new cardiomyocyte generation in the adult mammalian heart. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1659. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04083-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bei Y, Fu S, Chen X, Chen M, Zhou Q, Yu P. Cardiac cell proliferation is not necessary for exercise-induced cardiac growth but required for its protection against ischaemia/reperfusion injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:1648–1655. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weeks KL, McMullen JR. The athlete's heart vs. the failing heart: can signaling explain the two distinct outcomes? Physiology (Bethesda) 2011;26:97–105. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00043.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMullen JR, Shioi T, Zhang L, Tarnavski O, Sherwood MC, Kang PM. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110α) plays a critical role for the induction of physiological, but not pathological, cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12355–12360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934654100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBosch B, Treskov I, Lupu TS, Weinheimer C, Kovacs A, Courtois M. Akt1 is required for physiological cardiac growth. Circulation. 2006;113:2097–2104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weeks KL, Bernardo BC, Ooi JYY, Patterson NL, McMullen JR. The IGF1-PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in mediating exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy and protection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1000:187–210. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-4304-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neri Serneri GG, Boddi M, Modesti PA, Cecioni I, Coppo M, Padeletti L. Increased cardiac sympathetic activity and insulin-like growth factor-I formation are associated with physiological hypertrophy in athletes. Circ Res. 2001;89:977–982. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi L, Okabe I, Bernard DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A, Nussbaum RL. Proliferative defect and embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a deletion in the p110α subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10963–10968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo J, McMullen JR, Sobkiw CL, Zhang L, Dorfman AL, Sherwood MC. Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates heart size and physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9491–9502. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9491-9502.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bostrom P, Mann N, Wu J, Quintero PA, Plovie ER, Panakova D. C/EBPβ controls exercise-induced cardiac growth and protects against pathological cardiac remodeling. Cell. 2010;143:1072–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryall KA, Bezzerides VJ, Rosenzweig A, Saucerman JJ. Phenotypic screen quantifying differential regulation of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy identifies CITED4 regulation of myocyte elongation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;72:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bezzerides VJ, Platt C, Lerchenmuller C, Paruchuri K, Oh NL, Xiao C. CITED4 induces physiologic hypertrophy and promotes functional recovery after ischemic injury. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e85904. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manoury B, Montiel V, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide synthase in post-ischaemic remodelling: new pathways and mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:304–315. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson MG, Ellison GM, Cable NT. Basic science behind the cardiovascular benefits of exercise. Heart. 2015;101:758–765. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bekhite MM, Finkensieper A, Binas S, Muller J, Wetzker R, Figulla HR. VEGF-mediated PI3K class IA and PKC signaling in cardiomyogenesis and vasculogenesis of mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1819–1830. doi: 10.1242/jcs.077594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1205–1253. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–3027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratt AJ, MacRae IJ. The RNA-induced silencing complex: a versatile gene-silencing machine. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17897–17901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandes T, Barauna VG, Negrao CE, Phillips MI, Oliveira EM. Aerobic exercise training promotes physiological cardiac remodeling involving a set of microRNAs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H543–H552. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00899.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ooi JY, Bernardo BC, McMullen JR. The therapeutic potential of miRNAs regulated in settings of physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Future Med Chem. 2014;6:205–222. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Liang Y, Li Y. Non-coding RNAs in exercise. NCRI. 2017;1:10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gourdie RG, Dimmeler S, Kohl P. Novel therapeutic strategies targeting fibroblasts and fibrosis in heart disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:620–638. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:549–574. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Thatcher JE, DiMaio JM, Naseem RH, Marshall WS. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13027–13032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soci UP, Fernandes T, Hashimoto NY, Mota GF, Amadeu MA, Rosa KT. MicroRNAs 29 are involved in the improvement of ventricular compliance promoted by aerobic exercise training in rats. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:665–673. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00145.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carden DL, Granger DN. Pathophysiology of ischaemia-reperfusion injury. J Pathol. 2000;190:255–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<255::AID-PATH526>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang KR, Liu HT, Zhang HF, Zhang QJ, Li QX, Yu QJ. Long-term aerobic exercise protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury via PI3 kinase-dependent and Akt-mediated mechanism. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1579–1588. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Zhang H, Zhang C. Role of inflammation in the regulation of coronary blood flow in ischemia and reperfusion: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X, Xiao J, Zhu H, Wei X, Platt C, Damilano F. miR-222 is necessary for exercise-induced cardiac growth and protects against pathological cardiac remodeling. Cell Metab. 2015;21:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baggish AL, Hale A, Weiner RB, Lewis GD, Systrom D, Wang F. Dynamic regulation of circulating microRNA during acute exhaustive exercise and sustained aerobic exercise training. J Physiol. 2011;589:3983–3994. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.213363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi J, Bei Y, Kong X, Liu X, Lei Z, Xu T. miR-17-3p contributes to exercise-induced cardiac growth and protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Theranostics. 2017;7:664–676. doi: 10.7150/thno.15162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y, Bei Y, Shen S, Zhang J, Lu Y, Xiao J. MicroRNA-222 promotes the proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells by targeting P27 and TIMP3. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:282–292. doi: 10.1159/000480371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wisloff U, Loennechen JP, Currie S, Smith GL, Ellingsen O. Aerobic exercise reduces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and increases contractility, Ca2+ sensitivity and SERCA-2 in rat after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:162–174. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melo SF, Barauna VG, Neves VJ, Fernandes T, Lara Lda S, Mazzotti DR. Exercise training restores the cardiac microRNA-1 and -214 levels regulating Ca2+ handling after myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:166. doi: 10.1186/s12872-015-0156-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu SZ, Marcinek DJ. Skeletal muscle bioenergetics in aging and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s10741-016-9586-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kavanagh T, Mertens DJ, Hamm LF, Beyene J, Kennedy J, Corey P. Prediction of long-term prognosis in 12 169 men referred for cardiac rehabilitation. Circulation. 2002;106:666–671. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000024413.15949.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wisloff U, Stoylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rognmo O, Haram PM. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. 2007;115:3086–3094. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haykowsky MJ, Liang Y, Pechter D, Jones LW, McAlister FA, Clark AM. A meta-analysis of the effect of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling in heart failure patients: the benefit depends on the type of training performed. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2329–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chicco AJ, McCune SA, Emter CA, Sparagna GC, Rees ML, Bolden DA. Low-intensity exercise training delays heart failure and improves survival in female hypertensive heart failure rats. Hypertension. 2008;51:1096–1102. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Souza RW, Fernandez GJ, Cunha JP, Piedade WP, Soares LC, Souza PA. Regulation of cardiac microRNAs induced by aerobic exercise training during heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1629–H1641. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00941.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McMullen JR, Jennings GL. Differences between pathological and physiological cardiac hypertrophy: novel therapeutic strategies to treat heart failure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klattenhoff CA, Scheuermann JC, Surface LE, Bradley RK, Fields PA, Steinhauser ML. Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;152:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandes T, Hashimoto NY, Magalhaes FC, Fernandes FB, Casarini DE, Carmona AK. Aerobic exercise training-induced left ventricular hypertrophy involves regulatory MicroRNAs, decreased angiotensin-converting enzyme-angiotensin ii, and synergistic regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin (1-7) Hypertension. 2011;58:182–189. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang L, Li Y, Wang X, Mu X, Qin D, Huang W. Overexpression of miR-223 tips the balance of pro- and anti-hypertrophic signaling cascades toward physiologic cardiac hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:15700–15713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.715805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ajit SK. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and signaling molecules. Sensors (Basel) 2012;12:3359–3369. doi: 10.3390/s120303359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baggish AL, Park J, Min PK, Isaacs S, Parker BA, Thompson PD. Rapid upregulation and clearance of distinct circulating microRNAs after prolonged aerobic exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014;116:522–531. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01141.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rong X, Jia L, Hong L, Pan L, Xue X, Zhang C. Serum miR-92a-3p as a new potential biomarker for diagnosis of Kawasaki disease with coronary artery lesions. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2017;10:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12265-016-9717-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simha V, Qin S, Shah P, Smith BH, Kremers WK, Kushwaha S. Sirolimus therapy is associated with elevation in circulating PCSK9 levels in cardiac transplant patients. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2017;10:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s12265-016-9719-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roca E, Nescolarde L, Lupon J, Barallat J, Januzzi JL, Liu P. The dynamics of cardiovascular biomarkers in non-elite marathon runners. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2017;10:206–208. doi: 10.1007/s12265-017-9744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bye A, Rosjo H, Aspenes ST, Condorelli G, Omland T, Wisloff U. Circulating microRNAs and aerobic fitness—the HUNT-Study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fasanaro P, D'Alessandra Y, Di Stefano V, Melchionna R, Romani S, Pompilio G. MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand Ephrin-A3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15878–15883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800731200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu X, Cheng Y, Zhang S, Lin Y, Yang J, Zhang C. A necessary role of miR-221 and miR-222 in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal hyperplasia. Circ Res. 2009;104:476–487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.185363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng Y, Liu X, Zhang S, Lin Y, Yang J, Zhang C. MicroRNA-21 protects against the H2O2-induced injury on cardiac myocytes via its target gene PDCD4. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mooren FC, Viereck J, Kruger K, Thum T. Circulating microRNAs as potential biomarkers of aerobic exercise capacity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H557–H563. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00711.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uhlemann M, Mobius-Winkler S, Fikenzer S, Adam J, Redlich M, Mohlenkamp S. Circulating microRNA-126 increases after different forms of endurance exercise in healthy adults. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:484–491. doi: 10.1177/2047487312467902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aoi W, Ichikawa H, Mune K, Tanimura Y, Mizushima K, Naito Y. Muscle-enriched microRNA miR-486 decreases in circulation in response to exercise in young men. Front Physiol. 2013;4:80. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Small EM, O'Rourke JR, Moresi V, Sutherland LB, McAnally J, Gerard RD. Regulation of PI3-kinase/Akt signaling by muscle-enriched microRNA-486. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4218–4223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000300107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Y, Yao M, Zhou Q, Cheng Y, Che L, Xu J. Dynamic regulation of circulating microRNAs during acute exercise and long-term exercise training in basketball athletes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:282. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]