ABSTRACT

Background:

Given the importance of having valid information about the prevalence and reasons of self-medication among pregnant women for preventing self-medication during this period, this study aimed to systematically review and perform a meta-analysis on the prevalence and reasons of self-medication during pregnancy.

Methods:

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in 2018 to estimate the overall self-medication prevalence based on the database sources PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, MagIran, IranMedex and SID. Required data were collected using keywords: medication, self-medication, over-the-counter, non-prescription, prevalence, etiology, and occurrence and pregnant. Descriptive and cross-sectional studies in English and Persian languages were included. There was no time limitation for search. R software was applied for meta-analysis. Random-effects model was applied to estimate the self-medication prevalence with 95% confidence interval. Q statistics and I2 were used to measure the heterogeneity.

Results:

Out of 490 retrieved articles, finally 13 studies were included in meta-analysis, 6 studies of which reported the cause of self-medication. The overall estimated prevalence of self-medication based on the random effect model was 32% (95% CI, 22% - 44%). The most important reasons of self-medication were previous experience of the disease. The most important group of disease in which patients self-medicated was anemia. Also, the most important group of medication was herbal.

Conclusion:

The results of this study showed that the prevalence of self-medication among pregnant women was relatively high and required effective interventions to reduce and prevent self-medication among this group. Providing required information and raising awareness about complications resulting from self-medication, in particular herbal medicines and dietary supplements, should be taken into account.

KEYWORDS: Meta-Analysis , Pregnant , Prevalence , Self-medication

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, the excessive use of medicines and generally self-medication is considered as one of the major health and socio-economic problems in different countries.1-3 Self-medication is defined as the acquisition and use of one or more medicines without a physician’s opinion or diagnosis as well as without prescription or therapeutic monitoring, including the use of herbal or synthetic medicines.4-6 Currently, self-medication has caused an increase in factors such as bacterial resistance, lack of optimal treatment, unwanted and even deliberate poisoning, side effects, and adverse events. Furthermore, dysfunction of medicines market, loss of financial resources and increase in per capita consumption of medicines in the community.7-12

Due to extensive complications of self-medication, attention to complications resulting from self-medication among people in a society is a matter of great importance; furthermore, attention to female population due to being in sensitive periods, such as pregnancy and lactation as well as their more contact with family members and being role model for other family members is an additional issue of importance so that it can be said that the occurrence of pregnancy can easily increase the use of medicines and chemicals among women, while self-medication during this period accounts for more than 3% of congenital anomalies.13-16 On the other hand, various studies showed that women, especially, tend to self-medicate and often frequently use medicines to treat problems such as dysmenorrhea, menopause symptoms, menstrual disorders, mood disorders, prevention of osteoporosis as well as complications during pregnancy and lactation.17-19

Thus, due to the high prevalence of self-medication during pregnancy and its excessive adverse events during this period for both mothers and infants,20-22 conducting effective interventions to reduce and prevent self-medication during pregnancy is a matter of great importance. These interventions can include enhancing people’s knowledge about the consequences of self-medication, educating physicians and pharmacists about appropriate prescription of medicines, and counseling to medicines users as well as providing brochures and catalogs on a large scale. However, the successful implementation of these interventions requires having accurate information on the prevalence and reasons of self-medication during this period. In recent years, studies have been conducted on the reasons and prevalence of self-medication, although limited, in different countries; however, these studies do not provide a comprehensive and clear view for authorities and policymakers in the health system for decision-making and planning, because these studies were conducted in small areas and with low sample size. In this regard, the results of these studies should be gathered and analyzed systematically. This study aimed to systematically review and perform a meta-analysis of the prevalence and reasons of self-medication during pregnancy around the world.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

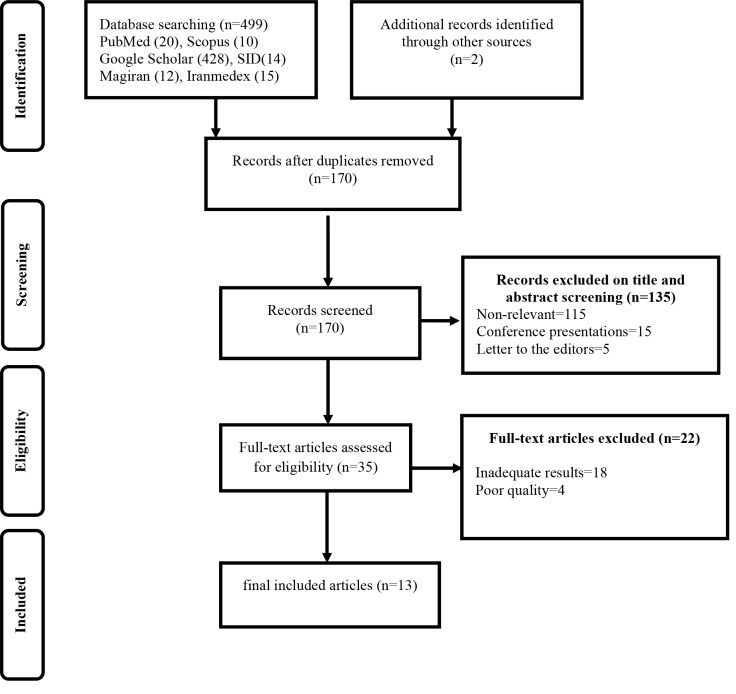

The systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in 2018, using the approach adopted in the book “A Systematic Review to Support Evidence-Based Medicine”. 23 Moreover, we followed the guidelines for conducting and reporting meta-analyses Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analysis (PRISMA).24 The PRISMA statement consists of a 27-item checklist and a 4-phase flow diagram consisting of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. The key element in this process is to identify the best available studies on the topic of interest by designing a screening protocol with sound eligibility criteria.25

Review of the Literature (Identification): In order to identify all relevant publications reporting the prevalence of self-medication in pregnant women, data were collected through searching following keywords: medication, self-medication, over-the-counter, non-prescription, prevalence, etiology, occurrence, pregnant women and pregnant in PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, MagIran, IranMedex, and Scientific Information Database (SID). Published articles were studied in English and Persian languages (Table 1 shows the search strategy for PubMed databases). The related journals and websites were searched manually and the reference lists of the selected articles were also checked. Finally, we also searched the gray literature and consulted with experts. Due to the limited number of studies, there was no time limitation for search. Also, since time limitation had no significant effect on the results, the authors decided not to apply time limitation.

Table 1.

Complete search strategy for PubMed databases

| Set | Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | (((self-medication [Title]) OR Medication [Title]) OR over-the-counter [Title]) OR non-prescription [Title] | 2987 |

| #2 | (((prevalence OR etiology) OR occurrence) | 9856646 |

| #3 | ((pregnant women [Title]) OR pregnant[Title]) | 38960 |

| #1 AND #2 AND #3 * | 20 |

Filters activated: Journal Article, Full text, Publication date to 2018/01/01, Humans, English

Data extraction (Screening): In the first step of article selection, articles with non-relevant titles were excluded by two reviewers (M.M, S.A.A). Then, in the second step, the abstracts and full texts of the articles were reviewed in order to include those articles matching the inclusion criteria. Reference management (Endnote X5) software was utilized to organize and assess the titles and abstracts and identify duplicate articles. Disagreements in each step were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (A.M). Abstracts were reviewed by two authors independently (M.M. and S.A.) and selected based on consensus if they met the study criteria. Data were extracted from the included articles, using a standard data collection form and for each study, information about the study characteristics, sample size, self-medication prevalence, drug group, type of disease, and reasons of self-medication was reported.

Quality assessment (Eligibility): Two reviewers (M.N. and S.G.Sh.) evaluated the articles on the basis of the ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology’ (STROBE) checklist.26 This checklist has 43 questions and the highest score was 45. The studies with a score of over 40 were selected as articles with adequate quality.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Included): The studies with adequate quality that focused on prevalence of self-medication in the pregnant women, cross-sectional studies and those published in English or Persian Languages were included. Conference presentations, case reports, interventions, proceedings and qualitative studies were excluded from the analysis. Articles were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

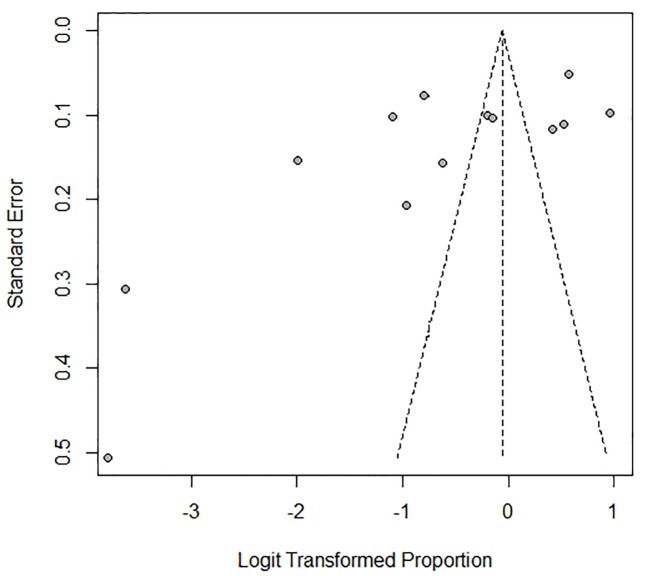

Data analysis: R software version 2.14 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was applied for meta-analysis; it estimates the overall self-medication prevalence (event rate). The meta-analysis was performed, using a random-effects model to estimate the self-medication prevalence, with 95% confidence interval. Q statistics and I2 were used to measure heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50% is considered as heterogeneity). To identify and reduce the source of heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis was done. Publication bias was assessed through the funnel plot. Funnel plot is a useful tool to visually assess the potential publication bias.27 In the funnel plot, the X-axis represents the mean result and the Y-axis shows the sample size or an index of precision.28 Microsoft Office Excel 2010 was used to draw the graph.

RESULTS

In this study, out of 501 articles, finally 13 articles completely related to the study objects were included13,14,16-19,21,29-34(Figure 1).

Figure1.

Flow diagram for study selection for systematic review

Based on the searches in PubMed, out of 20 papers retrieved, 9 were removed due to duplicates. Also, in the title, abstract and full-text screening, 7 cases were also excluded; finally, 4 articles were finally included in the study (Table 1).

The results of the extracted data from the entered articles are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The results of the extracted data from the articles entered

| Author, year | Country | Sample size | Design | Self-medication prevalence(%) | Drug group(%) | Type of disease(%) | Cause of Self-medication(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marwa, KJ et al: 2018 | Tanzania | 372 | Cross sectional | 46.2 | - Antimalarial (24.42) | - Malaria (32.56) | ||

| - Antibiotics (9.58) | -Urinary Tract Infection (9.3) | |||||||

| - Antiemetic (34.30) | - Morning Sickness (25.55) | |||||||

| - Analgesics (19.19) | - Heartburn (2.34) | |||||||

| - Antiasthma (1.74) | - Headache (19.19) | |||||||

| - Antiepileptic (1.16) | - Asthma (1.74) | |||||||

| - Antihypertensive (1.16) | - Epilepsy (1.16) | |||||||

| - Cough & Cold Remedies(5.23) | - Hypertension (1.6) | |||||||

| - Heartburn (1.74) | - Cough & Cold (5.25) | |||||||

| - Antihelmintics (1.16) | - Diarrhoea (1.58) | |||||||

| - Helminth’s (1.58) | ||||||||

| - Fungal Infection (0.58) | ||||||||

| Joseph, BN et al: 2017 | Nigeria | 350 | Cross-sectional | 62.9 | - know about the disease and-how it is treated (31.4) | |||

| - Previous use of medication(26.3) | ||||||||

| -Treatment for a minor ailment (19.8) | ||||||||

| - Recommendation from friends/acquaintances(7) | ||||||||

| - Saves time(7) | ||||||||

| - Cost effectiveness (6.4) | ||||||||

| Yusuff, KB et al: 2011 | Nigeria | 1650 | Prospective cross-sectional | 63.8 | -Paracetamol (34.3) | -Body pains/fever (30.1) | - accessibility/uncontrolled availability (40) | |

| - Hematinics + vitamins (33.8) | -Joint pain (14.5) | - long distance to public health facilities (29.6) | ||||||

| -Local herbs (11.7) | -Cough (10.2) | |||||||

| -Piroxicam (5.6) | -General weakness (9.2) | |||||||

| -Cough medicines (5.4) | -Indigestion (8.5) | |||||||

| -Dipyrone (2.7) | -Headache (7.8) | |||||||

| -Ampicilin (1.9) | -Sleeplessness (7.6) | |||||||

| -Chloramphenicol (1.6) | -Nausea (7.2) | |||||||

| -Prednisolone (1.4) | -Heart burn (2.5) | |||||||

| -Diazepam (0.8) | -Body swelling (2.4) | |||||||

| -Calcium supplements (0.8) | ||||||||

| Bagheri, A et al: 2014 | Iran | 303 | Cross- | sectional | 60.5 | |||

| Ziayee , T et al: 2008 | Iran | 180 | Descriptive, Cross-sectional | 2.2 | -Chemical(2.2) | |||

| -Herbal(84.2) | ||||||||

| -Acetaminophen | ||||||||

| -Amoxicillin | ||||||||

| -Antihistamines | ||||||||

| -Cold | ||||||||

| -Fluoxetine | ||||||||

| -Ranitidine | ||||||||

| Shamsi, M and Bayati, A: 2010 | Iran | 400 | Descriptive, Cross-sectional | 12 | - Antibiotics(48) | - anemia (55) | -Ignorance of the disease(58) | |

| - Cold(43) | - Digestive (46) | - Not having health insurance(56) | ||||||

| - Iron tablet(40) | - Respiratory (34) | -High costs of visit (54) | ||||||

| - Sedatives(38) | - Neurological disease(24) | -Previous experienve of disease(51) | ||||||

| - Antipyretic (26) | - headache(22) | -Lack of access to physician(44) | ||||||

| -Acetaminophen(24) | - Dermatological (18) | -Not enough time(40) | ||||||

| - Multivitamins(22) | -Previous use of medication(34) | |||||||

| - Folic acid(21) | -Convenient Access(32) | |||||||

| -Easy to buy without prescription(26) | ||||||||

| -Ensure the safe medication(24) | ||||||||

| -Lack of information on the effects of drugs(23) | ||||||||

| Ghaneie, R et al: 2013, | Iran | 116 | Descriptive, Cross-sectional | 27.6 | - Analgesics(15) | -No time to see the doctor(13.8) | ||

| - Antibiotics(5) | -High costs of visit (22.4) | |||||||

| - Vitamins(4) | -Underestimate the problem(47.4) | |||||||

| - Digestive(3) | -Fear of having a serious illness(11.2) | |||||||

| -Lack of physician trust(5.2) | ||||||||

| Baghianimoghadam, M. H.et al:2013, | Iran | 180 | Descriptive- analytic cross-sectional | 35 | ||||

| Sattari, M et al: 2012, | Iran | 400 | Cross-sectional | 44.9 | herbal medicine | |||

| Afshary, P. et al: 2015 | Iran | 801 | Descriptive-analytical | 31 | -Convenient Access(5.2) | |||

| -Mild Disease(19.8) | ||||||||

| -Previous experience of disease(49) | ||||||||

| -Ignorance of the disease(4.2) | ||||||||

| -Costly medical expenses(35.4) | ||||||||

| -Lack of healthcare insurance(2.1) | ||||||||

| -Lack of time(2.1) | ||||||||

| -The drug at home(2.1) | ||||||||

| -Experiencing good Result from self-medication(15.6) | ||||||||

| - Lack of physician trust (3.1) | ||||||||

| Abasiubong, F: 2012, | Nigeria | 518 | Cross-sectional | 72.4 | -fever/pain relievers (41.9) | protection from witches and witchcrafts, preventing pregnancy from coming out, for blood: poor sleep, fever and vomiting and infections. | ||

| -mixture of herbs and other drugs(9.1) | ||||||||

| -sedatives(4.0) | ||||||||

| -kolanuts(1.3) | ||||||||

| Abeje G, et al: 2015, Northwest | Ethiopia | 510 | Cross-sectional | 25.1 | -modern medication(68.7) | -Less Costly (6.25) | ||

| -traditional(21.1) | -Underestimate The problem(22.6) | |||||||

| - Long Waiting time(11.7) | ||||||||

| - Previous Use Of medication(11.7) | ||||||||

| Liao, Sh. et al:2015 | China | 422 | Cross-sectional | 2.6 | ||||

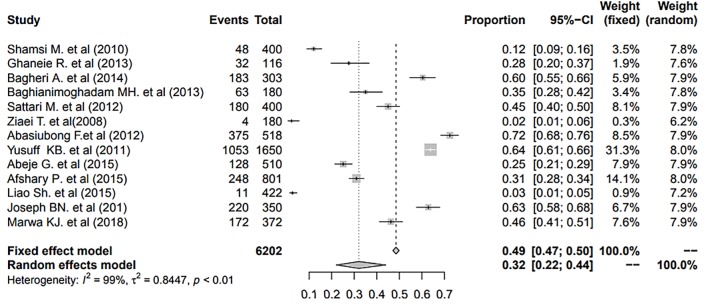

In the 13 articles reviewed, 6202 individuals had been studied. The highest prevalence was observed in Nigeria (72.4) and lowest in Iran (2.2). The overall prevalence of self-medication in pregnant women is shown in Figure 2.

Figure2.

The overall prevalence of self-medication in pregnant women according to random effect model

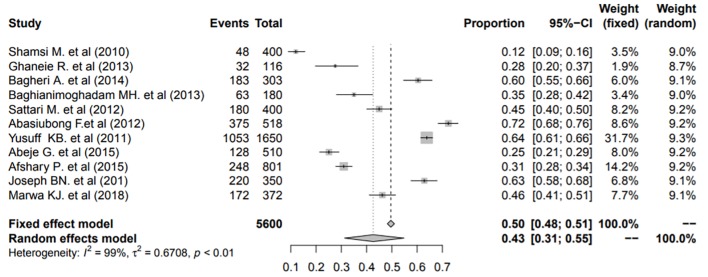

The overall prevalence of self-medication in pregnant women based on the random effect model was determined to be 32% (95% CI, 22% - 44%). 95% CI for the prevalence was drawn for each study in the horizontal line format (Q=885.9, df=12, P<0. 01 I2= 99, Tau2: 0.84). Due to high heterogeneity of the results, sensitivity analysis was done after excluding Ziayee et al. (2008) and Liao et al.’s (2015) studies. The results showed that after sensitivity analysis, heterogeneity improved considerably (Figure 3). (Q=689, df=10, P<0. 01, I2= 99, Tau2: 0.67). After this change, the overall prevalence of self-medication based on the random effect model was determined to be 43%.

Figure3.

The overall prevalence of self-medication in pregnant women after sensitivity analysis (excluding Ziayee et al. (2008) and Liao et al.’s (2015) studies)

To evaluate the publication bias, we applied funnel plot (Figure 4). The result of this funnel plot showed that there was the possibility of publication bias among the studies.

Figure4.

Funnel plot of standard error by event rate

According to the findings, the most common drug groups the pregnant women self-medicated were herbal (48%), nutritional agents (27.1%), analgesics and antipyretic (25%), antibiotics (20.9%), vitamins (19.9), and sedatives and hypnotics (16.5%). Also, the most common diseases for which the pregnant women self-medicated were anemia (55%), respiratory (34%), digestive (27.3%), neurological (24%), cough and cold (19.5%), dermatological (18%), headache (16.3%) and articular health problems (14.5%).

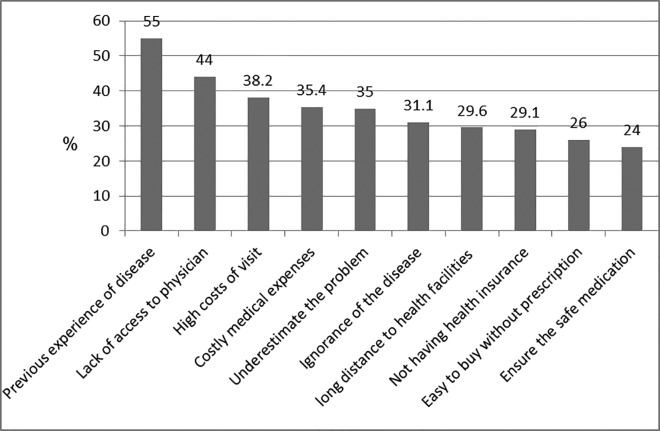

The most common reason of self-medication are shown in Figure 5.

Figure5.

The most common reasons of self-medication in pregnant women

As shown in Figure 5, the most important self-medication determinant factors were previous experience of disease, lack of access to physicians, and high costs of visit.

DISCUSSION

The results of the current study showed that the overall prevalence of self-medication among pregnant women in the world is about 32% although the results show high heterogeneity. However, a sensitivity analysis was done to improve it. This rate is similar to the results of a systematic review which investigated self-medication among the elderly.35 Results of a review study also showed that the prevalence of self-medication among the adolescents varies from 2 to 92%.36 Despite the expected higher prevalence of self-medication in pregnant women than other groups, due to pregnancy complications, the results of the current study, compared with findings of the studies conducted in the field,37-41 showed that self-medication among pregnant women compared to other groups in general was relatively low. One of the important reasons for this issue could be pregnant women’s fear of the effects of self-medication on their fetuses because self-medication in pregnant women due to fetal abnormalities is more sensitive in other people and the consumption of medicines during pregnancy is considered as an important factor for fetal abnormalities.42 Also, during recent years, initiatives and interventions, such as enhancing knowledge of people about the consequences of self-medication, educating physicians and pharmacists about appropriate prescription of medicines and counseling to medicine users as well as providing brochures and catalogs on a large scale were planned and implemented, in particular for pregnant women, which could be effective in this regard.31,43-47 However, given the sensitivity and risks of self-medication during pregnancy, 32 percent (more than one third of pregnant women) is a high rate and serious initiatives should be taken into account by authorities and health systems managers as well as families, in turn, in order to prevent and reduce the issue.

Herbal medicines and dietary supplements were the most medicine groups arbitrarily consumed by pregnant women. In a study which investigated self-medication among the elderly, painkillers were the most arbitrarily consumed medicines.35 In another studies, painkillers were also the most arbitrarily consumed medicines.48 Also, many other studies reported a significant relationship between female gender and self-medication of painkillers.49-51

Anemia was the most common problem for the treatment of which pregnant women arbitrarily used medicines. Some studies conducted on self-medication also reported anemia as the most important disease for the treatment of which self-medication is common.52-54

During pregnancy, the need to iron for pregnant women’s body significantly increases. During pregnancy, the blood gradually increases up to 50 percent of the normal level. Additional iron is needed to produce enough hemoglobin for this blood volume. During this period, extra iron is required for the fetus and placenta.55 Given that in this study dietary supplements were the second medicines groups used arbitrarily, pregnant women probably prepared and used iron supplements arbitrarily. Since arbitrary use of dietary supplements, in particular iron without physician consultation, may have a bad effect,56 dietary supplements, especially iron, should not be available without physician prescription for people and pregnant women; also sufficient trainings in this regard should be provided.

The results of the study showed that the most reasons for self-medication was previous experience of the disease. This issue was similar to the most studies conducted in the field of self-medication.57-61 Given that the majority of diseases and discomforts of pregnancy such as nausea and vomiting are usually repeated periodically, and also some diseases and conditions are experienced during first pregnancies, women often prefer to deal with these similar situations and conditions using previous prescribed medicines.

The limitation of this study was the fact that we had no access to some databases and also the included articles were only in the English and Persian languages. Also, according to the number of studies, it was not possible to categorize the articles based on the type of criteria. Another limitation of the current study was high possibility of publication bias and heterogeneity in the results; in this regard, the authors recommended that when using the results of this study, readers should pay attention to this issue.

Strengths of this paper was that examination of integrated assessment provides wide and deep information about various aspects of self-medication in pregnant women (prevalence, common drug groups which pregnant women self-medicated, most common self-medicated groups of diseases and most common reasons of self-medication) that can be used by policymakers and health care providers in decision-making and holding effective interventions to prevent self-medication in pregnant women.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study showed that the prevalence of self-medication among pregnant women has been relatively high and requires effective measures and interventions to reduce and prevent self-medication among this group. Providing the required information and raising awareness about complications resulting from self-medication, in particular herbal medicines and dietary supplements should be taken into account. Educating physicians and pharmacists about prescribing proper and adequate quantity of medicines, avoiding the provision of medicines without physician prescription, increasing pregnant women’s access to maternal care services, reducing the costs of maternal care services and building culture using public media in order to decrease self-medication can be taken into consideration. Due to the importance of publication bias in systematic reviews, it is recommended that researchers apply funnel plot to assess the publication bias.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was funded and supported by Health Management and Economics Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences; Grant no.25525.

Conflict of Interest:None declared.

REFRENCES

- 1.Abasaeed A, Vlcek J, Abuelkhair M, Kubena A. Self-medication with antibiotics by the community of Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:491–7. doi: 10.3855/jidc.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad A, Patel I, Mohanta G, Balkrishnan R. Evaluation of self medication practices in rural area of town sahaswan at northern India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4:S73–8. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.138012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eticha T, Mesfin K. Self-medication practices in Mekelle, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masoudi Alavi N, Alami L, Taefi S, Shojae Gharabagh G. Factor analysis of self-treatment in diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:761. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gul H, Omurtag G, Clark PM, et al. Nonprescription medication purchases and the role of pharmacists as healthcare workers in self-medication in Istanbul. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:PH9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehuys E, Gevaert P, Brusselle G, et al. Self-medication in persistent rhinitis: overuse of decongestants in half of the patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asseray N, Ballereau F, Trombert-Paviot B, et al. Frequency and severity of adverse drug reactions due to self-medication: a cross-sectional multicentre survey in emergency departments. Drug Saf. 2013;36:1159–68. doi: 10.1007/s40264-013-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grantham G, McMillan V, Dunn SV, et al. Patient self-medication--a change in hospital practice. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:962–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeiffer K, Some F, Muller O, et al. Clinical diagnosis of malaria and the risk of chloroquine self-medication in rural health centres in Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:418–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pretet S, Perdrizet S, Poisson N, et al. Treatment compliance and self-medication in asthma in France. Eur Respir J. 1989;2:303–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shamsi M, Tajik R, Mohammadbegee A. Effect of education based on Health Belief Model on self-medication in mothers referring to health centers of Arak. J Arak Uni Med Sc. 2009;12:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuefeng L, Keqin R, Xiaowei R. Use of and factors associated with self-treatment in China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:995. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abasiubong F, Bassey EA, Udobang JA, et al. Self-Medication: potential risks and hazards among pregnant women in Uyo, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afshary P, Mohammadi S, Najar S, et al. Prevalence And Causes Of Self-Medication In Pregnant Women Referring To Health Centers In Southern Of Iran. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2015;6:612–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bello FA, Morhason-Bello IO, Olayemi O, Adekunle AO. Patterns and predictors of self-medication amongst antenatal clients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2011;52:153–7. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.86124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghaneie R, Hemmati Maslakpak M, Baghi V. Self-Medication in Pregnant Women. J Res Dev Nurs Midwifery. 2013;10:92–8. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abeje G, Admasie C, Wasie Factors associated with self medication practice among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care at governmental health centers in Bahir Dar city administration, Northwest Ethiopia, a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:276. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.276.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamsi M, Bayati A. A survey of the Prevalence of Self-medication and the Factors Affecting it in Pregnant Mothers Referring to Health Centers in Arak city. Pars Journal of Medical Sciences. 2009;7:34–42. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yusuff KB, Omarusehe LD. Determinants of self medication practices among pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33:868–75. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Mvo Z. Indigenous healing practices and self-medication amongst pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2002;6:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao S, Luo B, Feng X, et al. Substance use and self-medication during pregnancy and associations with socio-demographic data: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2015;2:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macartney S, Whyte M. New moms and self medication. Can Nurse. 1995;91:47–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan K, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine. 2nd ed. Florida: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151:W–65W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLeroy KR, Northridge ME, Balcazar H, et al. Reporting guidelines and the American Journal of Public Health’s adoption of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:780–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallin J, Ognibene F. Principles and practice of clinical research. 3rd ed. Massachusetts: Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagheri A, Eskandari N, Abbaszadeh F. Self-medication and Supplement Use by Pregnant Women in Kashan Rural and Urban Areas. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;24:151–7. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ziayee T, Ozgoli G, Yaghmaei F, Akbar Zadeh A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of pregnant women about self-medication during pregnancy in health care centers affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Journal of Nursing & Midwifery. 2008;18:35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baghianimoghadam MH, Mojahed S, Baghianimoghadam M, et al. Attitude and practice of pregnant women regarding self-medication in Yazd, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:580–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sattari M, Dilmaghanizadeh M, Hamishehkar H, Mashayekhi SO. Self-reported Use and Attitudes Regarding Herbal Medicine Safety During Pregnancy in Iran. Jundishapur Journal of Natural Pharmaceutical Products. 2012;7:45–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marwa KJ, Njalika A, Ruganuza D, et al. Self-medication among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Makongoro health centre in Mwanza, Tanzania: a challenge to health systems. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18:16. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1642-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joseph B, Ezie IJ, Aya BM, Dapar MLP. Self-medication among Pregnant Women Attending Ante-natal Clinics in Jos-North, Nigeria. International Journal of TROPICAL DISEASE & Health. 2016;21:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jerez-Roig J, Medeiros LF, Silva VA, et al. Prevalence of self-medication and associated factors in an elderly population: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2014;31:883–96. doi: 10.1007/s40266-014-0217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shehnaz S, Agarwal AK, Khan N. A systematic review of self-medication practices among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:467–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klemenc-Ketis Z, Hladnik Z, Kersnik J. Self-medication among healthcare and nonhealthcare students at University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Med Prin Pract. 2010;19:395–401. doi: 10.1159/000316380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phalke VD, Phalke DB, Durgawale PM. Selfmedication practices in rural Maharashtra. Indian. J Community Med 2006;31:34–5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jafari F, Khatony A, Rahmani E. Prevalence of self-medication among the elderly in Kermanshah-Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7:360–5. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n2p360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pandya RN, Jhaveri KS, Vyas FI, Patel VJ. Prevalence, pattern and perceptions of self-medication in medical students. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 2013;2:275–80. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abahussain E, Matowe LK, Nicholls PJ. Self-reported medication use among adolescents in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2005;14:161–4. doi: 10.1159/000084633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaves RG, Lamounier JA, Cesar CC. Self-medication in nursing mothers and its influence on the duration of breastfeeding. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2009;85:129–34. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson WJ, Edwards SA, Roberts AW, Keller RJ. Comprehensive self-medication program for epileptic patients. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1978;35:798–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Degener JE, et al. Determinants of self-medication with antibiotics in Europe: the impact of beliefs, country wealth and the healthcare system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:1172–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowe CJ, Raynor DK, Courtney EA, et al. Effects of self medication programme on knowledge of drugs and compliance with treatment in elderly patients. BMJ. 1995;310:1229–31. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz D. Safe self-medication for elderly outpatients. Am J Nurs. 1975;75:1808–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hardon AP. The use of modern pharmaceuticals in a Filipino village: doctors’ prescription and self medication. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:277–92. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaghaghi A, Asadi M, Allahverdipour H. Predictors of Self-Medication Behavior: A Systematic Review. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43:136–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furu K, Skurtveit S, Rosvold EO. Self-reported medical drug use among15-16 year-old adolescents in Norway. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2005;125:2759–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dyb G, Holmen TL, Zwart JA. Analgesic overuse among adolescents with headache: The Head-HUNT-Youth Study. Neurology. 2006;66:198–201. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000193630.03650.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lagerløv P, Holager T, Helseth S, Rosvold EO. [Self-medication with overthe-counter analgesics among 15-16 year-old teenagers] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2009;129:1447–50. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.09.32759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castel JM, Laporte JR, Reggi V, et al. Multicenter study on self-medication and self-prescription in six Latin American countries. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61:488–93. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akanbi OM, Odaibo AB, Afolabi KA, Ademowo OG. Effect of self-medication with antimalarial drugs on malaria infection in pregnant women in South-Western Nigeria. Med Princ Pract. 2005;14:6–9. doi: 10.1159/000081915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahebi L, Vahidi RG. Self-medication and storage of drugs at home among the clients of drugstores in Tabriz. Current Drug Safety. 2009;4:107–12. doi: 10.2174/157488609788172982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaime-Perez JC, Gomez-Almaguer D. Iron stores in low-income pregnant Mexican women at term. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:81–4. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(01)00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasmussen KM, Stoltzfus RJ. New evidence that iron supplementation during pregnancy improves birth weight: new scientific questions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:673–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sawair FA, Baqain ZH, Abu Karaky A, Abu Eid R. Assessment of self-medication of antibiotics in a Jordanian population. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18:21–5. doi: 10.1159/000163041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Widayati A, Suryawati S, de Crespigny C, Hiller JE. Self medication with antibiotics in Yogyakarta City Indonesia: a cross sectional population-based survey. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:491. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shankar PR, Partha P, Shenoy N. Self-medication and non-doctor prescription practices in Pokhara valley, Western Nepal: a questionnaire-based study. BMC Fam Pract. 2002;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al-Azzam SI, Al-Husein BA, Alzoubi F, et al. Self-medication with antibiotics in Jordanian population. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2007;20:373–80. doi: 10.2478/v10001-007-0038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tabiei S, Farajzadeh Z, Eizadpanah AM. Self-medication with drug amongst university students of Birjand. Modern Care. 2012;9:371–8. [In Persian] [Google Scholar]