Abstract

Previous studies have shown that people with schizophrenia have high rates of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA). Despite this, intervention studies to treat OSA in this population have not been undertaken. The ASSET (Assessing Sleep in Schizophrenia and Evaluating Treatment) pilot study investigated Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) treatment of severe OSA in participants recruited from a clozapine clinic in Adelaide. Participants with severe untreated OSA (Apnoea-Hypopnoea Index (AHI) > 30), were provided with CPAP treatment, and assessed at baseline and six months across the following domains: physical health, quality of sleep, sleepiness, cognition, psychiatric symptoms and CPAP adherence. Six of the eight ASSET participants with severe OSA accepted CPAP. At baseline, half of the cohort had hypertension, all were obese with a mean BMI of 45, and they scored on average 1.47 standard deviations below the normal population in cognitive testing. The mean AHI was 76.8 and sleep architecture was markedly impaired with mean rapid eye movement (REM) sleep 4.1% and mean slow wave sleep (SWS) 4.8%. After six months of treatment there were improvements in cognition (BACS Z score improved by an average of 0.59) and weight loss (mean weight loss 7.3 ± 9 kg). Half of the participants no longer had hypertension and sleep architecture improved with mean REM sleep 31.4% of the night and mean SWS 24% of the night. Our data suggests CPAP may offer novel benefits to address cognitive impairment and sleep disturbance in people with schizophrenia.

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a nocturnal breathing disorder caused by repeated collapse of the upper airway during sleep, resulting in repetitive arousal. OSA is associated with poor cardiovascular health due to physiological changes related to intermittent hypoxia, and reduced quality of life due to sleep disturbance (Al Lawati et al., 2009). Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) reverses these pathophysiological changes and improves quality of life. (Jing et al., 2008). OSA is prevalent in people with schizophrenia due to high rates of obesity (Galletly et al., 2012) and men with schizophrenia are 2.9 times more likely to have OSA than age matched general population controls (Myles et al., 2018). A recent systematic review estimated that 19–57% of people with schizophrenia suffer comorbid OSA (Myles et al., 2016); these rates are much higher than that seen in the general population (Heinzer et al., 2015). Despite this, there is minimal literature reporting outcomes following treatment of OSA in this population.

The standard treatment for OSA is nocturnal CPAP which involves wearing a face or nasal mask that applies a continuous pressure to splint the upper airway during sleep. Effective CPAP treatment prevents obstructive events that cause repetitive hypoxia and arousals; and restores normal sleep architecture. In general population studies, not all people with OSA can tolerate CPAP, and the duration of CPAP use per night impacts on the clinical efficacy (Weaver et al., 2007). Mean CPAP adherence of four hours per night is considered the minimum required for efficacy. Treatment outcomes and adherence rates for CPAP in people with schizophrenia have not been reported previously and would be valuable in determining whether treatment of OSA in this population is efficacious.

In the general population CPAP reverses morbidity associated with OSA including impaired cognition and vigilance, insulin resistance, and hypertension (Al Lawati et al., 2009; Jing et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2003). Ratings of quality of life, daytime sleepiness, depression and anxiety also improve with CPAP. Thus, treatment of OSA in people with schizophrenia could potentially improve not only cardiometabolic risk factors, but also neurocognitive and functional outcomes. OSA and schizophrenia (Afonso et al., 2011) are associated with disruptions to sleep architecture, as such it is also important to determine whether sleep architecture is normalized to the same extent in people with schizophrenia compared to the general population.

This pilot study examined subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia and comorbid OSA. Subjects undertook psychiatric, cardiometabolic, cognitive and quality of life assessments prior to undergoing treatment with CPAP. The participants were then followed longitudinally during 6 months of CPAP treatment to determine adherence, efficacy and acceptability of treatment, and changes in baseline measures. To our knowledge this is the first prospective assessment of CPAP usage in people with schizophrenia and comorbid OSA.

Specifically, we aimed to determine:

-

1.

The efficacy of and adherence to CPAP treatment in people with schizophrenia and comorbid OSA.

-

2.

Changes in anthropometric measurements before and following six months of CPAP treatment

-

3.

Changes in psychiatric symptoms, quality of life measures, sleep quality measures and cognitive measures before and during CPAP treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Population

Subjects were recruited from a psychiatric outpatient clinic in Adelaide, South Australia. Inclusion criteria included males and females aged 18–64 years, a current clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, currently prescribed clozapine and a diagnosis of severe OSA made during assessment in the ASSET study. Exclusion criteria included inability to provide informed consent and a diagnosis of sleep disordered breathing made prior to enrolment in the ASSET study. Subjects were recruited between January 2015 and March 2016. Ethics approval was provided by The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Ethics Committee. All participants gave written informed consent.

2.2. Measures

A trained research nurse collected data on each participant at baseline at the Lyell McEwin Hospital Research Department, South Australia. Demographic and anthropometric data was recorded on the day prior to or the day following at-home diagnostic polysomnography (PSG) and included age, sex, medical history, prescribed medications, height, weight, waist and neck circumference, body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm at the level of the iliac crest following two normal breaths. Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference ≥ 94 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women. Hypertension was diagnosed if the person had a systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or a diastolic pressure ≥ 85 mm Hg. Psychopathological measures included the Positive And Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987), Montgomery Asperger's Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Williams and Kobak, 2008) and Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) (Morosini et al., 2000). Cognition was assessed using the Brief Assessment of Cognition for Schizophrenia (BACS) (Keefe et al., 2008). The results of the BACS were recorded as Z scores across individual domains and as a total score for Verbal Memory (VM), Digit Sequencing (DIGI), Token Motor Task (TMT), Verbal Fluency (Fluency), Symbol Coding (SC), the Tower of London (TL) and Total z score (Total). A score of zero indicates that the participant is on par with the general population mean. Scores in the negative range indicate cognitive decrements and are presented as standard deviations below the normal population means. Validation studies in people with schizophrenia score 1.5 standard deviations below the normal population mean. Subjective sleep quality was assessed with the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989), severity of insomnia with Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (Morin et al., 2011), Restless Legs Scale (RLS) (Group, 2003), and sleep related quality of life with Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) (Weaver et al., 1997).

Following recruitment and baseline measures subjects underwent at-home eight channel PSG performed using an Embletta ×100 (Natus Medical Inc., USA) or Somte (Compumedics, Australia) portable sleep recorder administered in the participants home by a trained psychiatric registrar. PSG data were manually staged by a BRPT registered Sleep Technician supervised by a board registered sleep physician at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health (ASIH) using the 2007 AASM alternate criteria to obtain an Apnoea-Hypopnoea Index (AHI) (Iber et al., 2007).

Eight subjects had an AHI > 30 events/h and were considered to have severe OSA, all were offered and accepted CPAP titration. We targeted an AHI > 30 events/h because this severity of OSA has been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events. Five of the participants then underwent laboratory-based CPAP titration overnight with additional PSG recording and one underwent at-home APAP titration using a Respironics REMstar Auto System (Philips, Netherlands). One subject underwent at-home APAP titration at their request. One subject failed CPAP titration due to discomfort in the laboratory setting and one developed nausea when using the mask. Both of these subjects declined at-home titration. The remaining six formed the cohort reported in this paper. These six subjects were provided with CPAP machines from the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health and received routine clinical care from this service consisting of an initial physician review and a one-hour education session with a trained CPAP nurse. Ongoing care included physician follow up with an associated nurse review every three months and phone contact from the nurse between reviews.

The PSG data provided a range of sleep measures including AHI, mean apnoea/hypopnea duration, longest apnoea duration, number of desaturations < 90%, total sleep duration, sleep latency, duration of each stage of sleep, duration of slow wave sleep (SWS), total sleep time, duration of non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, sleep efficiency, number of arousals and REM latency.

Participants were followed up after six months of CPAP use using the same anthropometric, psychopathological, cognitive and sleep quality measures as at baseline.

CPAP usage was determined by analyzing subject specific CPAP telemetry recorded using Encore Anywhere (Philips, Netherlands) software. Recorded CPAP adherence data included mean daily CPAP usage, percentage usage of >4 h, mean hourly usage on days used, average usage across all days, percentage of night with large leaks, average AHI and average snoring index.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcome was efficacy of CPAP treatment determined by changes in sleep architecture and AHI, and adherence to CPAP. Secondary outcomes were changes in anthropometric measures, psychopathological measures, sleep quality measures and cognition at six-month follow-up.

2.4. Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24 (IBM, New York). We present descriptive statistics including frequencies, means and standard deviations. No inferential statistics were performed due to the small sample size.

3. Results

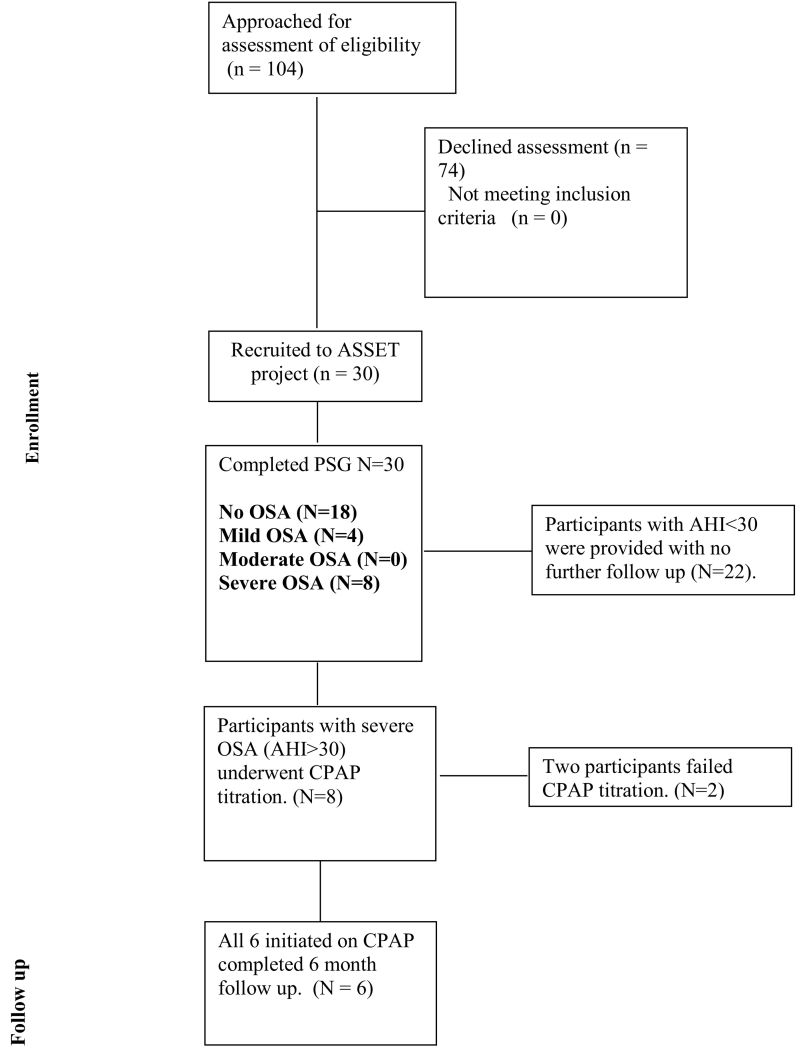

104 subjects were approached for at-home PSG screening as part of the ASSET pilot study. 30 subjects were recruited and underwent baseline study measures of whom 8 were diagnosed with severe OSA. Reasons for declining participation in at-home PSG screening were not collected in these non-consenting patients. Eight subjects from the ASSET study with severe OSA (AHI > 30 events/h) were offered CPAP, six (5 male, 1 female) of whom successfully underwent CPAP titration and completed six months of treatment (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram.

The sample was young and had high rates of obesity and hypertension. Mean age of the sample was 37.4 years (SD 12.3 years), mean BMI was 45 (SD 9.6 range: 36.4–62.1), mean waist circumference was 137.4 cm (SD 9.8 cm range: 126 cm–154 cm), mean neck circumference was 47.7 cm (SD 4.5 cm, range: 44 cm–53 cm), and mean AHI was 76.8 (SD 45, range: 40.2–134.5).

3.1. CPAP acceptability and sleep architecture pre and post-CPAP introduction

Five CPAP titrations occurred in the laboratory setting, allowing PSG to be recorded throughout CPAP initiation. PSG measures of sleep architecture at baseline and after CPAP of the five subjects are presented in Table 1. At baseline the sample had extremely severe OSA with AHIs that ranged from 37.6–134.5 (mean 83.3), and associated disruption of normal sleep architecture. The proportion of restorative SWS and REM sleep were reduced across the sample with mean time in SWS at baseline of 4.8% and mean time in REM of 4.1%. There was consistent improvement across these sleep domains with treatment, with REM sleep rebounding to 31.4% of the night and SWS 24% of the night.

Table 1.

Sleep architecture at baseline and immediately after CPAP initiation.

| ID | AHI |

% non-REM (stage 1&2 plus SWS) |

% slow wave sleep (SWS) |

% REM sleep |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | |

| 1 | 73.4 | 1.1 | 97.6 | 84.6 | 4 | 20.4 | 2.4 | 15.4 |

| 2 | 130.7 | 7.9 | 98.8 | 66.5 | 0.2 | 21.6 | 1.2 | 33.5 |

| 3 | 134.5 | 3.7 | 98.9 | 54.7 | 7.9 | 32.8 | 1.1 | 45.3 |

| 4 | 37.6 | 4.4 | 84.4 | 76.6 | 12.1 | 17.5 | 15.6 | 23.4 |

| 5 | 40.2 | 10.7 | 100 | 60.7 | 0 | 28.1 | 0 | 39.3 |

| Mean (SD) | 83.3 (47.2) | 5.5 (3.7) | 95.94 (6.5) | 68.62 (12) | 4.8 (5.2) | 24 (6.2) | 4.1 (6.5) | 31.4 (12) |

3.2. CPAP adherence

CPAP usage was assessed using Philips Encore Anywhere software. This allowed determination of residual AHI with treatment, mask leakage, snoring, and percentage of the night CPAP was being used. Usage data for the first month is presented in Table 2, and usage data for the first six months of treatment is presented in Table 3. CPAP use of >4 h per night is considered adequate adherence and is sufficient to substantially reverse levels of sleepiness (Weaver et al., 2007). In the six months of treatment the mean proportion of nights when CPAP was used for ≥4 h was 60%, and mean usage was 7.6 h/night, indicating adequate adherence. Mask leak and residual AHI are indicators of the effectiveness and proficiency with using CPAP. The average residual AHI across the first six months of treatment was 3.6 events/h and percentage of the night in large leak 9.7%, indicating adequate treatment effect.

Table 2.

CPAP usage during the first month of treatment.

| Days used | Percentage of days ≥4 h | Average usage in hours on days used | Average usage in hours on all days | Average % of the night in large leak | Average AHI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 | 61.3 | 6.1 | 4.7 | 0.3 | 2.2 |

| 2 | 19 | 35.5 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 8.5 |

| 3 | 30 | 96.8 | 9.2 | 8.9 | 4.4 | 4.8 |

| 4 | 29 | 84.4 | 7.75 | 7 | 21.7 | 1.7 |

| 5 | 14 | 37.5 | 9.5 | 4 | 6.7 | 4.4 |

| 6 | 29 | 80.6 | 8.75 | 8.15 | 35.2 | 7.3 |

| Mean (SD) | 24 days (6.5 days) | 66% (25%) | 7.6 h (2 h) | 5.9 h (2.4 h) | 11.6% (14%) | 4.8 (2.7) |

Abbreviations: Apnoea-Hypopnoea Index (AHI).

Table 3.

CPAP usage during the first six months of treatment.

| Days used | Percentage of days ≥4 h | Average usage in hours on days used | Average usage in hours on all days | Average % of the night in large leak | Average AHI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 148 | 67 | 6.85 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 115 | 39.6 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 6.8 |

| 3 | 177 | 89 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 6.8 | 1.9 |

| 4 | 109 | 53.5 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 11.8 | 1.5 |

| 5 | 72 | 34.6 | 8.8 | 3.5 | 8.4 | 2.7 |

| 6 | 158 | 78.3 | 8.75 | 7.5 | 26 | 7.3 |

| Mean | 130 days (38 days) | 60.3% (21.5%) | 7.6 h (1.4 h) | 5.4 h (2.1 h) | 9.7% (8.7%) | 3.6 (2.7) |

Abbreviations: Apnoea-Hypopnoea Index (AHI).

3.3. Physical health

Height, weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and neck circumference (NC) before and during treatment are presented in Table 4, blood pressure and heart rate before and during treatment are presented in Table 5. The participants had high rates of obesity and hypertension (100%) for such a young sample after six months of CPAP treatment, with no other interventions, five participants lost weight and three no longer had hypertension.

Table 4.

Weight, BMI, WC and NC changes after 6 months treatment with CPAP.

| ID | Age | Height | Weight |

BMI |

WC |

NC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | |||

| 1 | 26 | 176 | 192.5 | 183.3 | 62.14 | 59.79 | 154 | 151 | 53 | Missing |

| 2 | 40 | 170 | 136 | 125.3 | 47 | 43.01 | 135 | 133 | 53 | 46 |

| 3 | 30 | 175 | 142.4 | 121.3 | 46.5 | 39.61 | 139.5 | 134 | 43 | Missing |

| 4 | 45 | 181 | 133.2 | 126 | 40.69 | 38 | 140 | 124 | 45 | 43 |

| 5 | 26 | 186 | 125.8 | 131 | 36.4 | 37.86 | 130 | 134 | 44 | 44 |

| 6 | 57 | 158 | 92.6 | 92 | 36.86 | 36 | 126 | 120 | 48 | 46 |

| Mean (SD) | 137.1(32.3) | 129.8 (29.7) | 44.9 (9.5) | 42.4 (8.9) | 137.4 (9.7) | 137.2 (10.7) | 47.5 (4) | 44.6 (1.5) | ||

| Mean change (SD) | −7.3 (8.9) | −2.55 (2.8) | −4.7 (6.5) N = 5 |

−2.75 (3.0) N = 4 |

||||||

Abbreviations: continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), neck circumference (NC).

Table 5.

Blood pressure and HR changes after 6 months treatment with CPAP.

| ID | Systolic BP |

Diastolic BP |

Hypertensiona Y v N |

Heart rate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | |

| 1 | 139 | 145 | 75 | 88 | Y | Y | 95 | 106 |

| 2 | 127 | 121 | 88 | 87 | Y | Y | 88 | 93 |

| 3 | 134 | 109 | 79 | 74 | Y | N | 102 | 82 |

| 4 | 153 | 120 | 92 | 84 | Y | N | 90 | 92 |

| 5 | 133 | 143 | 92 | 80 | Y | Y | 116 | 102 |

| 6 | 154 | 129 | 97 | 81 | Y | N | 112 | 90 |

| Mean (SD) | 140 (11.1) | 127.8 (14.1) | 87.2 (8.5) | 82.3 (5.2) | 50% reduction in hypertension | 100.5 (11.6) | 94.2 (8.6) | |

| Mean change (SD) | −12.1 (18) | −4.8 (10.2) | −6.3 (14) | |||||

Hypertension was diagnosed if the person had a systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or a diastolic pressure ≥ 85 mm Hg.

3.4. Psychiatric symptom scales

Psychiatric symptom measures were recorded at baseline and after six months of CPAP therapy and are presented in Table 6. Higher scores on the PANSS indicates more severe psychosis, higher scores on the MADRS indicates more severe depression and higher scores on the PSP indicate better overall functioning. There were no observable changes in psychopathology scales in these participants. The baseline scores were below diagnostic and clinically significant ranges.

Table 6.

Psychiatric symptom scales before and after 6 months treatment with CPAP.

| ID | PANSS |

MADRS |

PSP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | |

| 1 | 73 | 62 | 4 | Missing | 49 | 60 |

| 2 | 42 | 54 | 2 | 2 | 72 | 60 |

| 3 | 86 | 92 | 12 | 4 | 33 | 37 |

| 4 | 43 | 57 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 61 |

| 5 | 63 | 67 | 6 | 10 | 60 | 60 |

| 6 | 54 | 52 | 4 | 0 | 60 | 50 |

| Mean | 60.2 (17.4) | 64 (14.8) | 4.8 (4.6) | 3.8 (3.8) | 55.6 (13.3) | 54.7 (9.6) |

| Mean change (SD) | 3.8 (9.3) | −1.0 (5.0) | −1.0 (8.7) | |||

Abbreviations: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS), Montgomery Aspergers Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

3.5. Sleep quality scales

Sleep quality measures were recorded at baseline and after six months of CPAP therapy and are presented in Table 7. Higher scores on the PSQI, FOSQ, ESS, ISI and RLS indicate worse sleep quality in those domains. Sleep quality and functional consequences of poor sleep did not consistently change with CPAP. Insomnia severity reduced consistently, but the threshold for clinical insomnia is a score of 15, and as such the baseline results were not within the diagnostic range for most participants.

Table 7.

Sleep quality measures before and after six months of CPAP.

| ID | PSQI |

FOSQ |

ISI |

RLS |

ESS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | |

| 1 | 7 | 11 | 30 | 35 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 7 | 8 | 39 | 31 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 10 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 19 | 27 | 16 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 3 |

| 4 | 5 | 4 | 36 | 39 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| 5 | 8 | 6 | 31 | 32 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 5 |

| 6 | 3 | 2 | 35 | 31 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Mean | 5.7 | 5.8 | 31.7 | 32.5 | 9.7 | 4 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 5.8 (4) | 5.4 (2.7) |

| Mean change (SD) | 0.16 (2.1) | 0.83 (5.91) | −5.6 (1.86) | 0.83 (6.43) | −0.4 (3.5) | |||||

Abbreviations: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Restless Leg Scale (RLS), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).

3.6. Cognition

Cognition was recorded at baseline and after six months of CPAP therapy using the BACS, the results are presented in Table 8. At baseline the mean BACS total Z score was −1.47 and Verbal memory (short term memory) −1.89. CPAP demonstrated improvements across several domains including Verbal memory 0.55 and the overall change was 0.59 (SD 0.25).

Table 8.

Brief Assessment of Cognition for Schizophrenia (BACS).

| VM |

DIGI |

TMT |

Fluency |

SC |

TL |

Total |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | Baseline | CPAP | |

| 1 | −2.35 | −1.63 | −0.81 | −2.08 | −2.24 | −0.52 | 1.05 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −1.06 | −0.81 |

| 2 | −1.31 | −0.38 | 0.46 | 1.22 | −0.52 | −0.38 | −0.35 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.62 | −0.16 | 0.41 |

| 3 | −3.50 | −2.46 | −3.59 | −2.58 | −1.57 | −0.38 | −2.16 | −2.33 | −2.52 | −2.2 | −1.31 | −1.03 | −3.64 | −2.73 |

| 4 | −0.69 | 0.66 | −0.56 | 0.71 | −1.18 | −1.18 | −0.19 | 0.22 | −0.45 | −0.29 | 1.17 | 1.45 | −0.47 | 0.39 |

| 5 | −2.25 | −2.35 | −1.57 | −0.05 | −0.12 | −0.38 | −1.83 | −1.5 | −1.33 | −0.69 | −0.48 | −0.75 | −1.88 | −1.43 |

| 6 | −1.21 | −1.83 | −1.82 | −0.81 | 0.01 | 1.2 | −0.52 | −0.68 | −1.4 | −0.85 | −1.58 | −1.58 | −1.62 | −1.13 |

| Mean | −1.89 | −1.33 | −1.32 | −0.6 | −0.93 | −0.27 | −0.67 | −0.59 | −0.82 | −0.56 | −0.3 | −0.2 | −1.47 | −0.88 |

| Mean change (SD) | 0.55 (0.75) | 0.71 (1) | 0.66 (0.8) | 0.085 (0.41) | 0.15(0.37) | 0.09 (0.23) | 0.59 (0.25) | |||||||

Abbreviations: verbal memory (VM), digit sequencing (DIGI), token motor task (TMT), verbal fluency (fluency), symbol coding (SC), Tower of London (TL).

4. Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates CPAP treatment is effective at normalizing sleep architecture disturbances in subjects with schizophrenia and comorbid severe OSA. Average measures of CPAP use were adequate at one month and were sustained over a six-month follow-up period. Average daily usage stabilized between 5 and 6 h on average whilst percentage of days with usage >4 h a night was maintained at or above 60% for the duration of follow-up. This latter criterion is the threshold for adequate CPAP adherence for clinical efficacy. CPAP adherence has not been investigated previously in schizophrenia, and our results indicate that this treatment is acceptable, and usage is sustained in the long term. After six months treatment, the AHI remained suppressed, indicating effective reversal of obstructive apnoea, and there was a reduction in time spent with mask leakage, indicating that subjects became more proficient at fitting their masks correctly.

Treatment with CPAP normalized sleep architecture with a rebound in REM sleep from an average of 4.1% to 31.4%, and a tripling of slow wave sleep. This may be important clinically as slow wave sleep is associated with rejuvenation and neuroendocrine homeostasis. Interestingly at follow-up after CPAP and in spite of substantial improvement in sleep architecture, there was little change in patient reported subjective sleep quality scales. There was a slight improvement in ISI scores, no change in FOSQ scores and a trend towards worsening of PSQI scores. A disconnect between objective functional outcomes and subjective impairment indicators have been previously noted in people with schizophrenia (Strassnig et al., 2018), our data similarly suggests subjective self-ratings are not an accurate reflection of objective sleep quality in people with schizophrenia.

Participants treated with CPAP had an average 7.3 kg weight loss at 6 months with an average 2.5 point reduction in BMI and an average 4.5 cm reduction in waist circumference. This is a novel finding that warrants further evaluation. Obesity is highly prevalent in people with schizophrenia and weight loss is difficult to achieve and maintain. All of our participants were taking clozapine, the most obesogenic antipsychotic drug. In the general population, treatment with CPAP is not associated with weight loss (Redenius et al., 2008). The loss of weight in our subjects may reflect improved vitality and an increase in physical activity; future studies should include objective measures of activity such as actigraphy to explore this possibility. In addition, restoration of normal oxygenation during sleep may be associated with a normalization of insulin resistance, which might advantageously influence macronutrient metabolism.

Hypertension also improved, with a mean reduction of 12.1 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure and 4.8 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure. All six participants met criteria for hypertension at baseline, but only three met these criteria at six months. These changes are consistent with general population studies of CPAP treatment in OSA (Martínez-García et al., 2013). At baseline all of our participants met criteria for obesity, all had at-risk waist circumference and all had hypertension. People with schizophrenia have much higher rates of metabolic syndrome than the general population (Galletly et al., 2012), and our findings indicate improvement in some of the components of metabolic syndrome.

Our subjects were relatively young (mean age 37.4 years, range 26 to 57). The early onset of obesity and metabolic disturbances in people with schizophrenia has been documented previously (Foley et al., 2013; Galletly et al., 2012). Our findings emphasize that OSA, like obesity and metabolic syndrome, can occur early in this population. Young people with the risk factors for OSA (obesity, elevated waist and neck circumference, smoking, alcohol abuse, sedating medications) should be screened using an objective measure such as home PSG, as they may well have undiagnosed OSA.

OSA is associated with cognitive deficits, particularly: attention, vigilance, short term/working memory, executive functioning and motor functioning. People with normal or low baseline cognitive function are more vulnerable to the cognitive deficits of OSA, and these deficits have been found to normalize with CPAP treatment (Barnes et al., 2004; Matthews and Aloia, 2011; Pan et al., 2015). The mechanisms underlying the cognitive deficits caused by OSA are poorly understood but may be explained to some degree by sleep fragmentation, sleep deprivation, hypoxia, chronic inflammation and cerebellar vascular damage. CPAP treatment improves performance across multiple cognitive domains (Pan et al., 2015) resulting in improved functional and occupational outcomes in the general population (Tregear et al., 2010). Translation of this benefit to people with schizophrenia and comorbid OSA would be an innovative means of modifying cognitive symptoms and real-world functional outcomes: currently an area of unmet clinical need. Our pilot results indicate that treatment of severe OSA with CPAP improves cognition in people with schizophrenia. Cognitive function improved with an average overall Z score improvement on the BACS of 0.59. Cognitive impairment is a major determinant of functional outcome in Schizophrenia (Green et al., 2000) and has been identified as a crucial target for treatment (MATRICS) (Green et al., 2004) but, as with obesity, achieving meaningful change has been difficult.

This study provides proof of concept that treatment of OSA with CPAP is feasible in people with schizophrenia and offers insight into the novel benefits treatment may have on sleep quality, cardiometabolic outcomes and cognition in this population. The diagnostic measures and treatment interventions undertaken in this study are standard practice, not investigational and importantly are broadly available and easily accessible in most public health services. We have demonstrated that the investigation and treatment of OSA is well tolerated and acceptable in a population of subjects with serious mental illness, thus indicating that stable schizophrenia itself is neither a barrier to effective treatment nor an excuse for clinical apathy when a sleep disorder is suspected. Further more highly powered randomized trials should be performed in the future to determine whether CPAP treatment of OSA comorbid with schizophrenia has a clinically relevant effect on cognitive and psychopathological symptoms.

4.1. Limitations

Whilst our results are important and encouraging, several limitations to our study should be acknowledged. Firstly, the small numbers and observational nature of the study do not allow causal inferences to be made from the follow-up data presented and are hypothesis generating only. Similarly, the absence of a control group makes it difficult to determine whether changes in cognition are independently associated with CPAP treatment, further controlled studies are required to validate our results. Measures of fasting blood sugar, cholesterol and triglycerides, and insulin resistance were not recorded and should be included in future studies of CPAP treatment of OSA in schizophrenia. Secondly, whilst our data does support the acceptability of PSG and CPAP these results may not be broadly generalisable to typical populations of people with psychotic illness. Whilst consecutive recruitment was undertaken, subjects refusing to participate in screening for OSA may have introduced selection bias where those less likely to adhere to CPAP were self-excluded from screening. Recruitment was also from a clozapine clinic, potentially representing a population where psychotic symptoms may be better controlled thus adherence to treatment more likely. Similarly, universal clozapine exposure may have biased results in our cohort as the effect of clozapine on sleep architecture is poorly understood. Clozapine is highly sedating and may confound interpretation of objective daytime sleepiness measures that have been validated in general populations. Thirdly, the study interventions and follow-up may have introduced bias in that subjects may have felt more encouraged to participate and adhere to treatment. We consider this unlikely however as the majority of the study was undertaken using pre-existing sleep services and standard follow-up.

5. Conclusion

People with schizophrenia commonly suffer lifetime disability due to severe, chronic functional impairment. Our pilot data indicates that effective treatment of OSA with CPAP therapy is achievable and well tolerated in people with schizophrenia and may improve cognition, sleep architecture and cardiometabolic measures, including blood pressure and weight. There is no previous published literature on the cognitive and physical outcomes before and after CPAP. Further research such as a randomized controlled trial of CPAP in people with schizophrenia and OSA, to determine whether CPAP leads to cognitive enhancement, improves functional outcomes and reduces cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors would be beneficial.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists New Investigator Grant.

References

- Afonso P., Viveiros V., Vinhas de Sousa T. Sleep disturbances in schizophrenia. Acta Med. Port. 2011;24(Suppl. 4):799–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Lawati N.M., Patel S.R., Ayas N.T. Epidemiology, risk factors, and consequences of obstructive sleep apnea and short sleep duration. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009;51(4):285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M., McEvoy R.D., Banks S., Tarquinio N., Murray C.G., Vowles N., Pierce R.J. Efficacy of positive airway pressure and oral appliance in mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;170(6):656–664. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1571OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse D.J., Reynolds C.F., Monk T.H., Berman S.R., Kupfer D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D.L., Mackinnon A., Watts G.F., Shaw J.E., Magliano D.J., Castle D.J., McGrath J.J., Waterreus A., Morgan V.A., Galletly C.A. Cardiometabolic risk indicators that distinguish adults with psychosis from the general population, by age and gender. PLoS One. 2013;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galletly C.A., Foley D.L., Waterreus A., Watts G.F., Castle D.J., McGrath J.J., Mackinnon A., Morgan V.A. Cardiometabolic risk factors in people with psychotic disorders: the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2012;46(8):753–761. doi: 10.1177/0004867412453089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.F., Kern R.S., Braff D.L., Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26(1):119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.F., Nuechterlein K.H., Gold J.M., Barch D.M., Cohen J., Essock S., Fenton W.S., Frese F., Goldberg T.E., Heaton R.K. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;56(5):301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group I.R.L.S.S. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2003;4(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzer R., Vat S., Marques-Vidal P., Marti-Soler H., Andries D., Tobback N., Mooser V., Preisig M., Malhotra A., Waeber G. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: the HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015;3(4):310–318. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00043-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iber C., Ancoli-Israel S., Chesson A., Quan S.F. American Academy of Sleep Medicine Westchester; IL: 2007. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. [Google Scholar]

- Jing J., Huang T., Cui W., Shen H. Effect on quality of life of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a meta-analysis. Lung. 2008;186(3):131–144. doi: 10.1007/s00408-008-9079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S.R., Fiszbein A., Opler L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe R.S., Harvey P.D., Goldberg T.E., Gold J.M., Walker T.M., Kennel C., Hawkins K. Norms and standardization of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) Schizophr. Res. 2008;102(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García M.-A., Capote F., Campos-Rodríguez F., Lloberes P., de Atauri M.J.D., Somoza M., Masa J.F., González M., Sacristán L., Barbé F. Effect of CPAP on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: the HIPARCO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2407–2415. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews E.E., Aloia M.S. Cognitive recovery following positive airway pressure (PAP) in sleep apnea. Prog. Brain Res. 2011;190:71–88. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53817-8.00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C.M., Belleville G., Belanger L., Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosini P.L., Magliano L., Brambilla L., Ugolini S., Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000;101(4):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles H., Myles N., Antic N.A., Adams R., Chandratilleke M., Liu D., Mercer J., Vakulin A., Vincent A., Wittert G. Obstructive sleep apnea and schizophrenia: a systematic review to inform clinical practice. Schizophr. Res. 2016;170(1):222–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles H., Vincent A., Myles N., Adams R., Chandratilleke M., Liu D., Mercer J., Vakulin A., Wittert G., Galletly C. Obstructive sleep apnoea is more prevalent in men with schizophrenia compared to general population controls: results of a matched cohort study. Australas. Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1039856218772241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y.-Y., Deng Y., Xu X., Liu Y.-P., Liu H.-G. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on cognitive deficits in middle-aged patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chin. Med. J. 2015;128(17):2365. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.163385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S.R., White D.P., Malhotra A., Stanchina M.L., Ayas N.T. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy for treating sleepiness in a diverse population with obstructive sleep apnea: results of a meta-analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163(5):565–571. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redenius R., Murphy C., Rsquo E., Al-Hamwi M., Zallek S.N. Does CPAP lead to change in BMI? J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2008;4(03):205–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassnig M., Kotov R., Fochtmann L., Kalin M., Bromet E.J., Harvey P.D. Associations of independent living and labor force participation with impairment indicators in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder at 20-year follow-up. Schizophr. Res. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregear S., Reston J., Schoelles K., Phillips B. Continuous positive airway pressure reduces risk of motor vehicle crash among drivers with obstructive sleep apnea: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2010;33(10):1373–1380. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.10.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T.E., Laizner A.M., Evans L.K., Maislin G., Chugh D.K., Lyon K., Smith P.L., Schwartz A.R., Redline S., Pack A.I., Dinges D.F. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep. 1997;20(10):835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T.E., Maislin G., Dinges D.F., Bloxham T., George C.F., Greenberg H., Kader G., Mahowald M., Younger J., Pack A.I. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30(6):711–719. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.B., Kobak K.A. Development and reliability of a structured interview guide for the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (SIGMA) Br. J. Psychiatry. 2008;192(1):52–58. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]