Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to 1) describe drug information desired by patients and 2) analyze how such information could be customized to be presented to patients according to their individual information needs.

Materials and methods

We performed a scoping literature search and identified relevant drug information topics by assessing and clustering 1) studies analyzing patients’ enquiries to drug information hotlines and services, and 2) qualitative studies evaluating patient drug information needs. For the two most frequently mentioned topics, we further analyzed which components (ie, information domains) the topics contained and examined patients’ and health care professionals’ (HCPs) views on these components.

Results

Of 27 identified drug information topics in the literature search, patients most frequently requested information on adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and drug–drug interactions (DDIs). Hypothetically, those topics are composed of seven distinct information domains each (eg, ADR and DDI classification by frequency, severity, or onset; information on management strategies, monitoring, and prevention strategies). Patients’ and HCPs’ appraisal concerning the information content of these domains varies greatly and is even lacking sometimes.

Conclusion

Patients particularly request information on ADRs and DDIs. Approaches to customize such information are sparse. The identified information domains of each topic could be used to structure corresponding drug information and to thus facilitate customization to individual information needs.

Keywords: medication information, information needs, customization, adverse drug reactions, side effects, drug-drug interactions

Introduction

Patient-centered care (PCC) emphasizes patient participation in decision making in order to foster the alliance between health care professionals (HCPs) and patients to share power and responsibility.1 Patients appreciate this approach and several studies indicated positive effects on health outcomes as PCC improves communication, patient involvement, patient-HCP relationship, and treatment adherence.2,3 A prerequisite for shared responsibility is the empowerment of patients based on the provision of understandable information that matches the individual patients’ information needs.3 With regard to drug treatment, patients who have received clear and reasonable treatment recommendations and advice are more likely to adhere to their treatment.4

This may be explained by the fact that basic information on drug treatment is mandatory to fulfill the “Five Rights”,5,6 ie, taking the right drug by the right patient in the right dose at the right time following the right technique to prevent unintentional non-adherence. However, in addition to such evident information needs, patients evaluate the benefits of prescribed drugs (necessity belief) and weigh it against their concerns (concern belief). While a profound “necessity belief” appears to predict adherence, a deeper “concern belief” may lead to non-adherence,7 which, in this context, is often called intentional non-adherence.8 Especially in chronic conditions (eg, hypertension) non-adherence is associated with increased overall health care costs, morbidity, and mortality.4 To efficiently address or prevent a patient’s concern and thereby mitigate at least one reason of non-adherence, the provision of subjectively desired information about treatment and drugs seems a promising approach.3

Which information is relevant to a patient depends on several factors including age, socio-economic status, and comorbidities.9 Depending on the patient’s preferences, both receiving “too much” of unsolicited information and receiving not enough information may have negative effects on patient empowerment, thus amplifying patient concerns. Therefore, it is crucial to customize information toward the individual needs of each patient.9 However, systematic data on which drug information patients want and how it should be edited are sparse.

Unmatched drug information needs are reflected in the growing use of online health information services. Taking Germany as an example, approximately half of its population uses the Internet to get health-related information, and especially services such as medication checks and drug–drug interaction (DDI) checks are frequently accessed.10

To satisfy such unmatched information needs, we aimed to 1) describe drug information desired by patients and 2) analyze how such information could be customized to be presented to patients according to their individual information needs.

Materials and methods

We followed the presumption that drug information can be divided into 1) basic drug information and 2) subjectively desired drug information. Basic drug information refers to drug information that is mandatory for every patient in order to be able to conduct the drug treatment following the concept of the “Five Rights”.5 Subjectively desired drug information, on the other hand, satisfies information customized to individual needs and considers concerns or beliefs with regard to the treatment.

While basic drug information often is straightforward, unambiguous, and therefore easily conveyed in medication schedules,11 no overview exists regarding scope and characteristics of subjective drug information needs.

To describe drug information desired by patients, an exploratory number of articles relating to patient information needs with one of the key words “patient information,” “drug information,” “medication information,” and “medicines information” in title/abstract, English or German language, and with a publishing date between January 2000 and February 2017 were searched. The search purposefully identified potentially relevant studies that were subsequently clustered into two groups: the first group 1) comprised studies analyzing patients’ enquiries to drug information hotlines and services, while the second group 2) comprised qualitative studies evaluating patient drug information needs. From the identified studies in the first group, the total number of drug-related enquiries, the enquiry topics, the provider of the information service, and the timeframe of data enquiry were extracted. The enquiry topics were classified according to those previously defined in the respective study by the authors. From the second group, the study design, population, study site, and raised drug information needs were extracted.

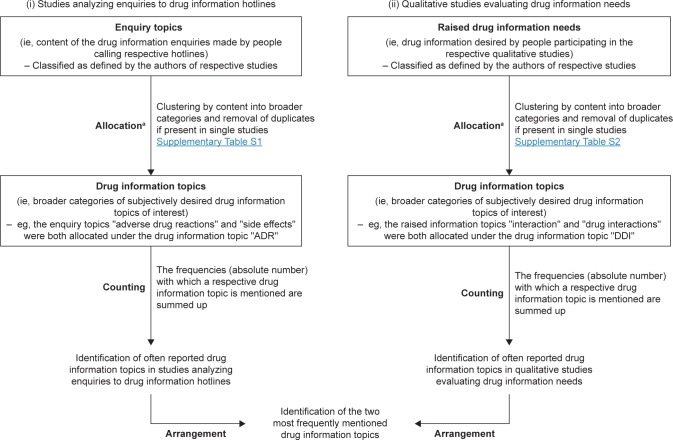

Subsequently, we clustered the different enquiry topics (extracted from studies analyzing patients’ enquiries) and the raised drug information needs (extracted from qualitative studies) as defined in the studies into drug information topics, therewith merging enquiry topics according to their content into broader categories that were consistently defined and applied in both study groups (Table S1 and S2). This allocation was conducted by two clinical pharmacists until concordance was reached (MK and VSW). When this was not possible, a third clinical pharmacist was consulted for clarification (HS). The drug information topics were then counted throughout the different studies and arranged according to frequency in order to identify the most often reported drug information topics and to define the two most frequently mentioned ones (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of information extraction from the identified studies and allocation in order to identify the most often reported drug information topics and to define the two most frequently mentioned ones.

Notes: aThe allocation was conducted by MK and VSW. If no agreement was reached, HS was consulted for clarification. Categories that were used for allocation were consistently defined and applied in both study groups (i) and (ii).

Abbreviations: ADR, adverse drug reaction; DDI, drug–drug interaction.

To analyze how such information could be customized in order to be presented to patients, we focused on the two most frequently mentioned information topics and assessed in more detail which components (ie, information domains) the topics contained. Subsequently, we evaluated patients’ and HCPs’ expectations toward the content and presentation of these information domains as described in the literature.

Results

Drug information desired by patients

We identified 12 studies analyzing patient enquiries to drug information hotlines and services.12–23 Most studies analyzed enquiries to drug information hotlines (number of studies [n]=10), while some analyzed enquiries to online information services (n=2). Studies originated from several countries, namely Australia (n=5), the Netherlands (n=2), Germany (n=2), Finland (n=1), United States of America (n=1), and the United Kingdom (n=1). Most of the studies were performed with data originating from the Australian drug information hotline “National Prescribing Service MedicineWise” (NPS MedicineWise) and comprised a plethora of drug-related patient enquiries, most of which were safety-related, such as information on adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and DDIs (Table 1). In the second group, 15 qualitative studies that addressed drug information needs with different methods and in different settings and populations were identified.24–38 Studies were conducted in different countries, namely the Netherlands (n=3), United States of America (n=2), the United Kingdom (n=2), Norway (n=1), China (n=1), Armenia (n=1), Germany (n=1), Singapore (n=1), Australia (n=1), Canada (n=1), and Belgium (n=1). In addition, the studies were conducted in various settings, which were community pharmacies (n=8), residents not recruited in direct health care setting (n=3), hospitals (n=2), practices (n=1), and senior centers (n=1). Various study designs were used in the studies, namely semi-structured interviews (n=7), questionnaires (n=5), focus group discussions (n=2), and presenting commonly asked questions to assess interest in these (n=1). Also, in these studies the majority of the drug information topics raised by the patients were safety-related, most frequently seeking information on ADRs and DDIs (Table 2). Yet, there seemed to be some differences based on study context and setting. Patients in senior centers and hospitals were not interested in information topics like “drugs and driving” and “drug use and alcohol”.27,34,38

Table 1.

Studies analyzing enquiry topics to drug information hotlines and services

| Study | Study characteristics | Enquiry topicsa as classified in the respective studies and sorted by descending frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crunkhorn et al12 | Analysis of (i) enquiries made by or concerning people aged 0–17 years and (ii) enquiries made by or concerning people >18 years to a MCC Provider: NPS Medicine Wise, Australia Time: September 2002–June 2010 Total number of enquiries: (i) 14,753 (ii) 98,117 |

(i) Made by or concerning people aged 0–17 years: 1. Lactation 2. Treatment/prophylaxis 3. Dose 4. Adverse drug reaction 5. Interaction 6. Vaccination |

(ii) Made by or concerning people aged >18 years: 1. Adverse drug reaction 2. Interaction 3. Treatment/prophylaxis 4. Mechanism/profile 5. Risk/benefit 6. Dose |

| Pijpers et al13 | Analysis of enquiries to a MCC related to drug use in pregnancy Provider: NPS Medicine Wise, Australia Time: September 2002–June 2010 Total number of enquiries: 1,166 |

Narrative questions and information seeking during pregnancy: 1. Preconception: effects on fertility 2. First trimester: safety of a specific drug 3. Second and third trimesters: preferred/safe treatment of a condition |

|

| Benetoli et al14 | Analysis of enquiries to a social networking site providing drug information Provider: Facebook®, information provider: NPS MedicineWise, Australia Time: October 2013–October 2014 Total number of enquiries: 226 |

1. Side effects 2. Treatment options 3. Drug interactions 4. Dose/administration 5. Mechanism/profile 6. Complementary medicines 7. Others (eg, cost/vaccination) 8. Pediatric 9. Pregnancy 10. Stability/storage/disposal/formulation |

|

| Kloosterboer et al15 |

Analysis of (i) cough and cold related and (ii) other enquiries to a MCC Provider: NPS Medicine Wise, Australia Time: September 2002–June 2010 Total number of enquiries (i) 5,503 (ii) 117,702 |

(i) Cough and cold related: 1. Interaction 2. Other types of concern 3. Pregnancy and lactation 4. Treatment/prophylaxis 5. Adverse drug reaction |

(ii) Other enquiries: 1. Other types of concern 2. Adverse drug reaction 3. Interaction 4. Treatment/prophylaxis 5. Pregnancy and lactation |

| Van De Belt et al16 | Analysis of enquiries asked in an online forum or during (phone/group) consultations by patients of an infertility clinic Clinic: Radboud University Medical Center, the Netherlands Total number of enquiries: 193 |

Most frequently asked questionsb 1. Medication: use/application 2. Schedule of treatment 3. Blood loss during treatment 4. Medication: side effects 5. Quality of oocyte/embryo/semen: lifestyle advices |

|

| Huber et al17 | Analysis of enquiries to a MCC available exclusively for patients Provider: Technical University Dresden, Germany Time: August 2001–January 2007 Total number of enquiries: 4,914 |

1. Adverse drug reaction 2. General information about drug 3. Information about therapy 4. Drug interactions 5. Indication/contraindication of drug 6. Cost/refund/prescription requirement/drug-related legislation 7. Self-medication/dietary supplement/alternative medicine/medical devices 8. Application/dosage of drug 9. Change of medication 10. Mechanism of drug action/pharmacokinetics 11. Pregnancy/breastfeeding |

|

| Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä et al18 | Analysis of enquiries to a community pharmacy-operated MCC Provider: Helsinki University Pharmacy, Finland Time: 1 week during August 2002 Total number of enquiries: 780 |

1. Costs and reimbursements 2. Drug–drug interactions 3. Dosage 4. Adverse effects 5. Indication 6. Efficacy 7. Drug use and alcohol 8. Effective substance 9. Mechanism of action 10. Taking medicine correctly 11. Contraindication 12. Storage 13. Breaking up medication 14. Safety of drugs during pregnancy 15. Formulation 16. Drugs and driving 17. Dependency |

|

| Maywald et al19 | Analysis of enquiries to a MCC available exclusively for patients Provider: Technical University Dresden, Germany Time: September 2001–September 2003 Total number of enquiries: 2,049 |

1. ADR (adverse drug reaction)/drug interaction 2. Information about drugs or therapies 3. Self-medication 4. Indications/contraindications 5. Dosage and administration 6. Pharmacokinetics 7. Refund and legalities 8. Miscellaneous |

|

| Assemi et al20 | Analysis of enquiries submitted to an online “Ask Your Pharmacist” drug information service Provider: University of California at San Francisco, USA Time: 1999–2000 Total number of enquiries: 1,087 |

1. Indications, efficacy, mechanism of action 2. Adverse effects 3. Other (non-health-related) 4. Other health-related questions 5. Drug identification 6. Drug–drug or drug–food interactions 7. Dosing issues 8. Pharmacokinetics (eg, time to onset of effects) 9. Drug stability |

|

| Weersink et al21 | Analysis of enquiries related to (i) antipsychotic drugs and (ii) rest of enquiries to a MCC Provider: NPS Medicine Wise, Australia Time: September 2002–June 2010 Total number of enquiries: (i) 6,295 (ii) 119,624 |

(i) Antipsychotic drugs: 1. Safety 2. Efficacy 3. Judicious use 4. Other |

(ii) Rest of enquiries: 1. Safety 2. Efficacy 3. Judicious use 4. Other |

| Marvin et al22 | Analysis of enquiries made by citizens to a hospital pharmacy drug information line Provider: Chelsea and Westminster Hospital London, United Kingdom Time: 6 months in 2008 Total number of enquiries: 500 |

1. Interaction 2. Directions 3. Side effect 4. Supply 5. Error 6. Safety in pregnancy 7. What is it for 8. Storage/expiry 9. Allergy 10. Unknown |

|

| Bouvy et al23 | Analysis of enquiries to (i) a toll-free drug information hotline and (ii) enquiries to a free drug information website Provider: Royal Dutch Association for the advancement of Pharmacy, the Netherlands/Private initiative website by volunteer pharmacists, the Netherlands Time: February 2000 Total numbers of enquiries: (i) hotline: 305 (ii) website: 183 |

(i) Hotline: 1. Adverse reactions/safety 2. General information on a specified drug 3. Interactions and alternative drugs and effectivity mechanism of action 4. Dependency and stopping 5. Therapeutic advice/comparison of products/changing of medications 6. Dosage and time schedule and general information on diseases and groups of drugs 7. Availability of the product/reimbursement 8. Second opinion 9. Pregnancy 10. Lactation 11. Information for school and use outside licensed indication |

(ii) Website: 1. General information on diseases and groups of drugs 2. Therapeutic advice/comparison of products/changing of medications 3. Adverse reactions/safety 4. Availability of the product/reimbursement 5. Alternative drugs 6. General information on a specified drug 7. Information for school 8. Effectivity mechanism of action 9. Dosage and time schedule 10. Use outside licensed indication 11. Pregnancy 12. Dependency and stopping 13. Interactions 14. Second opinion |

Notes:

Enquiry topics of studies, besides those by Pijper et al13 are listed according to their frequency in each individual study. In some studies, one call could contain more than one enquiry topic. Names of enquiry topics were extracted verbatim from the respective studies;

In total, there were 24 different themes according to which the patients’ questions were categorized.

Abbreviations: MCC, medicines call center; NPS MedicineWise, National Prescribing Service MedicineWise.

Table 2.

Qualitative studies evaluating patient drug information needs

| Study | Study characteristics | Raised drug information needsa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sage et al24 | Presenting parents of children with “attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder” a list of commonly asked questions to assess interest in these Population: 70 parents, mostly female Study site: Private pediatric practices, United States |

Questions of highest interest by parents (analogously extracted): • Long-term effects • Treatment • Side effects • Interaction • Dosage • Dosing schedule • Indication and side effects • Availability and drug name • Drug and driving |

|

| Abraham et al25 | Semi-structured interviews with thematic analysis to assess parents’ perspectives on pediatric medication Population: 19 parents, mostly female Study site: Community pharmacies, United States |

Essential drug information requested by parents: • Drug interactions • Side effects |

|

| Twigg et al26 | Questionnaire to measure medication information satisfaction of patients who (i) received an advanced counseling service and (ii) those who did not Population: Patients with more than one regular medicine, 232 assessed questionnaires Study site: Community pharmacies, United Kingdom |

Score for the potential problems (SIMS score 2), unsatisfied with information on: (i) Patients who received service • Whether the medication will affect your sex life • Whether the medicine interferes with other medicines • What are the risks of you getting side effects • What you should do if you experience unwanted side effects • Whether the medicine has any unwanted effects • Whether the medication will make you feel drowsy • Whether you can drink alcohol while taking this medicine • What you should do if you miss a dose |

Score for the potential problems (SIMS score 2), unsatisfied with information on: (ii) Patients who received no service • What are the risks of you getting side effects • Whether the medicine has any unwanted effects • Whether the medication will affect your sex life • Whether the medicine interferes with other medicines • What you should do if you experience unwanted side effects • What you should do if you miss a dose • Whether the medication will make you feel drowsy • Whether you can drink alcohol while taking this medicine |

| Mamen et al27 | Structured questionnaire to assess patients’ need for drug information Population: 162 elderly patients who used at least one prescription medicine Study site: Senior centers, Norway |

Information patients would like to have: • General information/everything • Side effects • How the drug works/what it does • Interactions • Indication of drug • Is it working/is it necessary • Duration of treatment • Other questions |

|

| Yi et al28 | Questionnaires for patients and physicians to identify gaps regarding medication education, content, and delivery Population: 108 ambulatory care patients, 116 hospital clinics physicians Study site: Outpatient pharmacy and hospital clinics, China |

Topics with largest difference between information desired by patients and received information: • What to do if adverse reaction experienced • Drug–food interactions • Drug–drug interactions • Adverse reactions • Onset of action • Duration of therapy • Medication storage |

|

| Kazaryan and Sevikyan29 | Interview to identify patients’ needs of drug information Population: 1,059 people who visited community pharmacies Study site: Community pharmacies, Armenia |

Information requested by patients: • Indication • Dosage and method of administration • Contraindications • Adverse reactions • Simultaneous use of multiple medicines • Information about medicine’s price |

|

| Mahler et al30 | Standardized questionnaires consisting of SIMS-D and MARS-D to assess the extent to which patients are satisfied with drug information Population: 834 chronically ill patients Study site: Heidelberg, Germany |

Score for the potential problems (SIMS score 2), unsatisfied with information on:b • What are the risks of you getting side effects • Whether the medication will affect your sex life • Whether the medicine has any unwanted effects • What you should do if you experience unwanted side effects • Whether the medicine interferes with other medicines • Whether the medication will make you feel drowsy • What you should do if you miss a dose • Whether you can drink alcohol while taking this medicine |

|

| Ho et al31 | Questionnaire to identify patients’ needs of drug information Population: 201 patients in an outpatient pharmacy Study site: Outpatient pharmacy of a university hospital, Singapore |

Information wanted: • Adverse effects • Dosing • Indication • Interactions (drug–drug, herb–drug) • Mechanism of action • Use of devices • Pregnancy or breastfeeding |

|

| Newby et al32 | Telephone survey to investigate information seeking behavior and questions asked about drugs by drug users with (i) satisfied and (ii) unmet needs of drug information Population: 61 residents who completed follow-up interviews Study site: Residents in New South Wales, Australia |

Questions asked about drugs: (i) Drug users with satisfied needs • Adverse effects • How well medicine worked for a particular condition • Advice on the best treatment for a particular condition • Other • Reason for taking the medicine • General inquiry about a medicine • How to use the medicine • Interactions • Pregnancy and lactation |

Questions asked about drugs: (ii) Drug users with unmet needs • Adverse effects • How well medicine worked for a particular condition • Other • Advice on the best treatment for a particular condition • General inquiry about a medicine • Reason for taking the medicine • How to use the medicine • Pregnancy and lactation • Interactions |

| van Geffen et al33 | Semi-structured telephone interviews to identify patients’ information needs when starting with SSRI treatment Population: 41 patients with first prescription of a SSRI Study site: Community pharmacies, the Netherlands |

Information wanted at start of treatment: • Delayed onset of action • Adverse effects • Dependency • Reasons for use • Consequences of long-term use • Interactions • Duration of treatment and discontinuation |

|

| Zwaenepoel et al34 | Standardized interviews to explore information preferences of psychiatrics inpatients Population: 279 psychiatric inpatients Study site: Psychiatric hospitals, Belgium |

Information wanted: • Side effects • How does the drug work? • What is drug taken for? • No further information • Addictive? • Interactions? • Harmful? |

|

| Lamberts et al35 | Semi-structured telephone interviews and patient focus group discussions to obtain insights into information needs of patients who have recently started treatment with oral antidiabetics Population: 42 patients with first prescription of an oral antidiabetic, 11 further participating in 2 focus groups Study site: Community pharmacies, the Netherlands |

Information wanted according to patients: • What your medicine is for • What you should do if you forget a dose • Whether the medicine interferes with other medicines • How to use your medicine • How long you will need to be on your medicine • How long it will take to act • Whether the medicine has any unwanted effects • How it works • What are the risks of stopping the medicine • What are the risks of you getting side effects |

|

| Nair et al36 | Focus groups to explore what patients want to know about their medication and how HCPs respond to these information needs Population: 88 patients who had taken at last one medication, 27 physicians, and 35 pharmacists in 19 focus groups Study sites: British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Canada |

Information topics discussed: • Side effects and risk information • Range of treatment options • How long to take medication • Cost of medication • Is this medication right for me? |

|

| Raynor et al37 | Focus groups to examine the experiences with drug information of people with a chronic illness Population: 23 patients with asthma participating in 4 focus groups Study site: Community pharmacies, United Kingdom |

Information need areas identified: • Name and purpose of treatment • When and how to take it; how long to take • Side effects and what to do about them • Problems with other drugs • How to tell if it is not working |

|

| Borgsteede et al38 | Semi-structured interviews to explore patients’ needs of information about their medication at hospital discharge Population: 31 patients being discharged from the hospital Study site: General teaching hospital, the Netherlands |

Information aspects important for patients: • Basic information (eg, drug name, indication, use) • Information about side effects • Information about alternatives • What to do when medication problems are encountered |

|

Notes:

In some studies, more than one information topic could be given by study participants;

The study used a German version of the SIMS; wording of the topics raised is according to the respective English version.

Abbreviations: HCP, health care professional; MARS, Medication Adherence Reporting Scale; SIMS, Satisfaction with Information about Medicines Scale; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

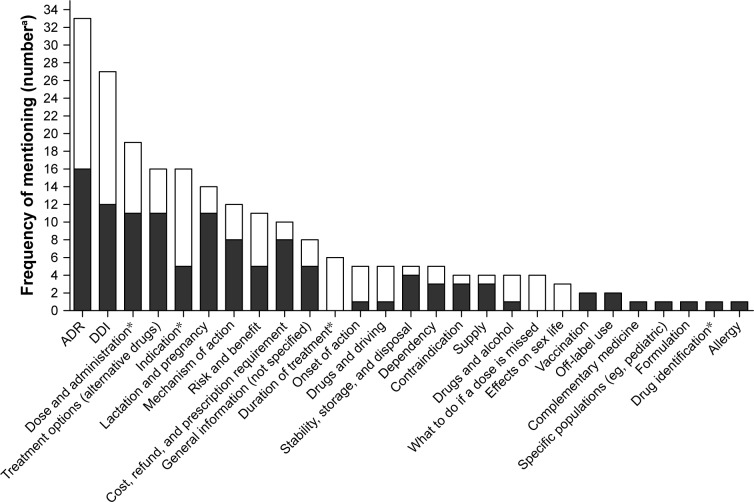

Some information topics like “cost, refund, and prescription requirement” and “stability, storage, and disposal” were predominantly mentioned in ambulatory settings (ie, pharmacies and residents).28,29,36 Such topics were also more often mentioned in studies analyzing patient enquiries to drug information hotlines and services. The majority of raised drug information topics were largely identical in the examined studies regardless of whether semi-structured interviews or questionnaires were used. Focus groups that were held between patients and researchers,36 and patients, physicians, and pharmacists,37 also freely discussed predominantly safety-related drug information topics in addition to information topics that can be considered to follow the principle of the “Five Rights,”5 such as “dose and administration,” “indication,” and “duration of treatment.” Arrangement of the allocated drug information topics according to frequency yielded ADRs and DDIs as the drug information topics most often sought by the patients regardless of country, setting, and study design. Other frequently requested drug information topics were dose and administration (ie, how and in which strength to take the drug), indication of a drug, and treatment options (ie, whether alternative drugs can be used to treat the condition). Selected topics of lower interest were information on vaccination, off-label use, drug formulation, and allergy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Arrangement of the allocated drug information topics according to frequency of mentioning in assessed 1) studies on drug information hotlines (solid bars) and 2) qualitative studies (open bars).

Notes: aThe frequencies (absolute number) with which a respective drug information topic was mentioned in the assessed studies were summed up. *Drug information topics that can be considered to be mandatory to conduct the drug treatment (“Five Rights”).

Abbreviations: ADR, adverse drug reaction; DDI, drug–drug interaction.

Customization of drug information

Both ADR and DDI information may be composed of seven different information domains each (Table 3): ADR information could be customized according to the frequency, severity, onset of ADRs (eg, start of therapy vs long-term effects), duration of ADRs (eg, long-term vs short-term), and management strategies including limitations of self-management (ie, how to minimize ADRs and when to consult a physician). Moreover, additional information could be given on appropriate monitoring and prevention strategies (eg, tools to cope with ADRs).

Table 3.

The two most frequently mentioned drug information topics and their information domains

| Drug information topic | Information domains | Amount of information desired by patients and implications in the literature | Health care professionals’ perceptions and worries |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADRs | Classification by • Frequency according to SmPC using qualitative EU guideline descriptions (ie, very common, common, uncommon, rare, very rare)46 |

• Some patients do not want any information33,38–41 • Some patients want a full disclosure of all possible ADRs36,38–41 • Some patients want specific ADR information categorized by frequency with common ADRs being of greater interest39,42–45 • Patients do not want physicians to tailor ADR information for them39 Implications in the literature • Using the qualitative EU guideline descriptions for frequency leads to massive overestimation of perceived risk46 • Meta-analysis: risk of ADRs should be quantified numerically47 • Higher desire for ADR information by patients with previous experiences of ADRs34,39,48 |

• Physicians and pharmacists question the amount of ADR information as a cause of non-adherence36,41,49–53 and know patients who do not want any information50 • Physicians and pharmacists differ on who should discuss ADRs with patients because each profession considers itself more capable or the other profession responsible for doing so33,41,49 Extent of ADR information during physician consultations • ADR information is often not part of consultations54 • Physicians are more likely to inform on ADRs that occur frequently52,53 |

| Classification by • Severity (ie, serious or non-serious ADRs) |

• Some patients do not want any information33,38–41 • Some patients want a full disclosure of all possible ADRs36,38–41 • Some patients want specific ADR information categorized by severity with dangerous ADRs being of greater interest39,42–45 • Patients do not want physicians to tailor ADR information for them39 Implications in the literature • Using the qualitative EU guideline descriptions for frequency leads to massive overestimation of perceived risk46 • Meta-analysis: risk of ADRs should be quantified numerically47 • Higher desire for ADR information by patients with previous experiences of ADRs34,39,48 |

• Physicians and pharmacists question the amount of ADR information as a cause of non-adherence36,41,49–53 and know patients who do not want any information50 • Physicians and pharmacists differ on who should discuss ADRs with patients because each profession considers itself more capable or the other profession responsible for doing so33,41,49 Extent of ADR information during physician consultations • ADR information is often not part of consultations54 • Severity does not seem to influence likelihood that physicians inform on ADRs52,53 |

|

| Classification by • Onset of ADRs (eg, start of therapy vs long-term effects) |

• Patients want information on ADRs occurring both early on and during long-term treatment33,37,55 | • No data available | |

| Classification by • Duration of ADRs (eg, long-term vs short-term) |

• No data available | • No data available | |

| Classification by • Management strategies including limitations of self-management (ie, how to minimize ADRs and when to consult a physician) |

• Patients want information on how to reduce ADRs33 | • No data available | |

| Additional information on • Monitoring |

• Patients want information on how to reduce ADRs33 | • No data available | |

| Additional information on • Prevention strategies |

• Patients want information on how to avoid ADRs33 | • No data available | |

| DDIs | Empowerment to identify interactions • Identification of interaction partners |

• Some patients believe that drugs counteract with each other when taken together, while some trust their prescriber that no DDIs will occur55 • Patients request information on interactions between prescription drugs and OTC medications (11.4%)56 • Patients request information on interactions between drugs and food (6.8%)56 • Patients are interested in identification of interaction partners because 62% of the female participants wanted to learn more about DDIs between hormonal contraceptives and antiepileptic drugs57 Implications in the literature • Focus should be put on interactions with OTC drugs and food58,59 • Patients fail to transfer knowledge on DDI management into practice60 |

• No data available |

| Classification by • Frequency (ie, the frequency with which a DDI may occur) |

• Patients request information on frequency (2.3%) and prevalence of DDIs (2.3%)56 | • No data available | |

| Classification by • Severity (ie, a serious or non-serious DDI effect) |

• Patients request information on seriousness (19.3%) and effects of DDIs (5.7%)56 | • No data available | |

| Classification by • Onset of DDIs (ie, most likely timing when a DDI occurs) |

• No data available | • No data available | |

| Additional information on • Management strategies including limitations of self-management (ie, how to minimize DDIs and when to consult a physician) |

• Patients request information on management of DDIs (eg, influence of timing and dose) (2.3%)56 | • No data available | |

| Additional information on • Monitoring |

• Patients request information on signs of DDIs (3.4%)56 | • No data available | |

| Additional information on • Prevention strategies |

• Patients request information on how to prevent DDIs (eg, influence of timing and dose) (2.3%)56 | • No data available |

Abbreviations: ADR, adverse drug reaction; DDI, drug–drug interaction; EU, European Union; OTC, over-the-counter; SmPC, Summary of Product Characteristics.

For DDIs, customization could refer to the identification of DDIs, frequency, severity, or onset of DDIs. Furthermore, additional information on management strategies including limitations of self-management, monitoring, and prevention strategies (eg, different timing, lower dosages, and alternative medicines) could be given.

The subsequent literature search illustrated some of these domains with patients’ needs and HCP perceptions regarding extent of information wanted because especially classification of ADRs by frequency and severity was often mentioned in the assessed literature. However, the majority of the domains were never extensively assessed in patients or HCPs. Hence, knowledge of whether and to which extent patients require the diverse elements of information and to what extent HCPs support them is limited.

Discussion

Patients request largely differing information on their drugs beyond the basic information of the “Five Rights” provided in medication schedules. Thereby, information needs verbal-ized in qualitative studies are reflected in actual enquiries to information hotlines and services. Undoubtedly, safety-related information on ADRs and DDIs is most often sought.30,37

In comparison to other drug information topics such as appropriate storage of drugs or indication of a drug, relevant information on ADRs and DDIs is broader and less explicit. Hence, if patients request information on ADRs, it typically remains unclear what they actually want to know. For instance, do patients want to learn only about the most frequent ADRs, or the most severe ones, or those they can independently monitor and manage? Nevertheless, such safety-related information might particularly interfere with patient concerns about their drug treatment and may hence also influence their adherence to drug treatment because lacking information might promote a deeper “concern belief” and thus non-adherence.7,8 Owing to the high diversity of ADR and DDI information, it is difficult to satisfy individual needs, identify information deficits, and provide missing details while avoiding to transfer information that is not sought or irrelevant in the current patient situation.

For both ADRs and DDIs, we identified seven distinct information domains that would allow for customizing information. Such customization would then enable HCPs to individually provide patients with the respective drug information of personal interest. Only little is published on patient attitudes toward these information domains and even fewer evidence exists on how patient needs could be assessed to identify unmet information needs.

For instance, there are patients who decline to receive additional information and treatment willingness of some patients already diminishes when the mere presence of possible ADRs is mentioned, regardless of their likelihood of occurrence.61 Often, this fear of potential non-adherence is put forward by HCPs who are reluctant to offer what they deem too much additional information. However, this fear is not reflected in literature.62,63

At the other extreme, some patients want a full disclosure of all possible ADRs. Indeed, patients often seem to follow a safety-conscious strategy and opt for a maximum of information without a real understanding of risk and likelihood.39,46 Furthermore, patients seem to be particularly interested in risks considered most threatening for their own well-being regardless of their likelihood of occurrence.44

The majority of patients probably is situated in between these two extremes, and while customization of information to satisfy individual needs is acknowledged,58 explicit endeavors remain scarce. Often, patients are left with patient information leaflets that follow a “one-size-fits-all” approach and the vast number of ADRs mentioned often causes undesirable emotional reactions (eg, fear) that might promote non-adherence.42 With regard to DDIs, some patients believe that a lot of drugs should not be combined because their efficacy could be altered, whereas other patients believe that co-prescribed medicines are unlikely to interact at all.55 Considering self-medication in particular, there is a need to inform patients and raise awareness about possible DDIs between prescribed drugs and those used in self-medication.

While extensive research has been undertaken to assess professional DDI checkers regarding their content, design, and use in a professional setting, there is very limited information on performance of DDI checkers informing patients and laypersons.64 Many available DDI checkers lack DDI severity information, contain only limited patient-oriented risk communication, and have only limited patient readability.64 Especially, lengthy and complex information on possible DDIs is not well understood.65 Future research is therefore necessary to facilitate 1) customization of ADR information and 2) customization of DDI information with advanced drug information management in order to enable customization possibilities. Besides enabling customization possibilities of drug information, a particular emphasis must be put on making this information easily accessible for future users (eg, patients). Therefore, in a subsequent step, low-threshold dissemination channels must be assessed and validated with patients.

A first step would be to develop, validate, and release a database that contains available drug information in commonly understood language and register that is structured according to relevant identified information domains (Table 3). Such a database would allow selecting only information domains important for the individual patient and would thus individualize information transfer. A second prerequisite would be a tool to assess and identify individual drug information needs and select information domains for which a patient wants additional information. There are already tools available to assess whether patients desire more or less information in general and about their drugs in particular, such as the “Extent of Information Desired” scale,9 and tools that help measuring overall satisfaction with drug information, such as the “Satisfaction with Information about Medicines Scale”.26,30 However, a tool to determine specific information domains on ADRs and DDIs to allow patients to select the amount and content of additional drug information is lacking. To recognize and identify boundaries and implications of customized drug information, it will be crucial on the one hand to identify patient populations benefiting from such a form of information. On the other hand, it will be equally important to find those patients who do not need additional information, and particularly those who are not served by such an approach while being in need of additional information – to this end, it may also be necessary to include further patient characteristics that influence information needs, predominantly the patient’s health literacy.66 Looking at the literature, high desires for information were expressed for instance by patients with diabetes diagnosis, whereas patients with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases expressed lower desires for drug information.9 Additional factors like diseases and comorbidities may therefore also influence individual information needs.9,34 How and in which way such influence takes place should consequently also be assessed.

Limitations

The present work has several limitations. First, we conducted a narrative instead of a systematic review and only assessed a single (albeit large) database (PubMed). However, our aim was to identify the most relevant drug information topics and highlight how such information can be customized. With a narrative approach we were able to include a broad spectrum of articles and therefore widely assess drug information needs. The topics extracted from PubMed articles showed strong consistency and little deviation of topics mentioned, therewith suggesting an already sufficient approach. Furthermore, while not applying the full range of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) statement, we still applied various checklist items in our review process whenever possible (eg, eligibility criteria, information sources, data collection progress, synthesis of results, study characteristics, summary of evidence, limitations, conclusions, and funding).67

Second, our approach to assess unsatisfied drug information needs by analyzing enquiries to drug information hotlines and services might be biased by the fact that actively calling a hotline requires some basic interest in drug-related topics and ambition to self-reliantly acquire information; therefore, more “empowered” and proactive patients may be selected by this approach and less empowered patients might be missed. Nevertheless, the second assessment of unmatched information needs including a variety of qualitative studies yielded similar results, supporting the conclusion that these findings indeed reflect the drug information needs of a broad population of patients.

Conclusion

Patients particularly request safety-related drug information that exceeds the typical scope of medication schedules. While it is well known that extent and content of the favored information can vary, evidence on how to assess information needs and correspondingly customize information is sparse. This review suggests that for both ADRs and DDIs, rather diverse but only limited information domains are needed and that individual patients largely differ with respect to their information needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Viktoria S Wurmbach (VSW) for her help in allocating the enquiry topics and raised drug information topics into broader categories (drug information topics). In addition, the authors thank the members of the “Cooperation Unit Clinical Pharmacy” for valuable input regarding the information domains for the two most frequently mentioned drug information topics. Part of this work was supported by the “Klaus Tschira Foundation gGmbH (KTS),” Heidelberg, Germany. The funding sources had no involvement in collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in the writing of the report. In addition, we acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the funding programme Open Access Publishing, by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts and by Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):1923–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Boer D, Delnoij D, Rademakers J. The importance of patient-centered care for various patient groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(3):405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(12):600–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Náfrádi L, Galimberti E, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. Intentional and Unintentional Medication Non-Adherence in Hypertension: The Role of Health Literacy, Empowerment and Medication Beliefs. J Public Health Res. 2016;5(3):762. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2016.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott M, Liu Y. The nine rights of medication administration: an overview. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(5):300–305. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.5.47064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haefeli WE. Verabreichungsfehler – welche Informationen braucht ein Patient um seine Arzneimittel-Therapie sicher durchzuführen? [Drug administration errors-what information is required to enable patients to safely take their drugs? Ther Umsch. 2006;63(6):363–365. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930.63.6.363. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vries ST, Keers JC, Visser R, et al. Medication beliefs, treatment complexity, and non-adherence to different drug classes in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(2):134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duggan C, Bates I. Medicine information needs of patients: the relationships between information needs, diagnosis and disease. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(2):85–89. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EPatient RSD GmbH . Press conference. EPatient Survey 2016. Berlin, Germany: Mar 3, 2016. [Accessed October 25, 2018]. Available from: https://dl.health-it-portal.de/topics/860/files/pressemappe_fachmedien_epatientsurvey2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botermann L, Krueger K, Eickhoff C, Kloft C, Schulz M. Patients’ handling of a standardized medication plan: a pilot study and method development. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:621–630. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S96431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crunkhorn C, van Driel M, Nguyen V, Mcguire T. Children’s medicine: What do consumers really want to know? J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(2):155–162. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pijpers EL, Kreijkamp-Kaspers S, Mcguire TM, Deckx L, Brodribb W, van Driel ML. Women’s questions about medicines in pregnancy – An analysis of calls to an Australian national medicines call centre. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;57(3):334–341. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benetoli A, Chen TF, Spagnardi S, Beer T, Aslani P. Provision of a Medicines Information Service to Consumers on Facebook: An Australian Case Study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(11):e265. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kloosterboer SM, Mcguire T, Deckx L, Moses G, Verheij T, van Driel ML. Self-medication for cough and the common cold: information needs of consumers. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(7):497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van De Belt TH, Hendriks AF, Aarts JW, Kremer JA, Faber MJ, Nelen WL. Evaluation of patients’ questions to identify gaps in information provision to infertile patients. Hum Fertil. 2014;17(2):133–140. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.912762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber M, Kullak-Ublick GA, Kirch W. Drug information for patients – an update of long-term results: type of enquiries and patient characteristics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(2):111–119. doi: 10.1002/pds.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä MK, Antila J, Eerikäinen S, et al. Utilization of a community pharmacy-operated national drug information call center in Finland. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2008;4(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maywald U, Schindler C, Krappweis J, Kirch W. First patient-centered drug information service in Germany – a descriptive study. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(12):2154–2159. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assemi M, Torres NM, Tsourounis C, Kroon LA, Mccart GM. Assessment of an online consumer “Ask Your Pharmacist” service. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(5):787–792. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weersink RA, Taxis K, Mcguire TM, van Driel ML. Consumers’ questions about antipsychotic medication: revealing safety concerns and the silent voices of young men. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(5):725–733. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-1005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marvin V, Park C, Vaughan L, Valentine J. Phone calls to a hospital medicines information helpline: analysis of queries from members of the public and assessment of potential for harm from their medicines. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(2):115–122. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2010.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouvy ML, van Berkel J, de Roos-Huisman CM, Meijboom RH. Patients’ drug-information needs: a brief view on questions asked by telephone and on the Internet. Pharm World Sci. 2002;24(2):43–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1015574315469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sage A, Carpenter D, Sayner R, et al. Online Information-Seeking Behaviors of Parents of Children With ADHD. Clin Pediatr. 2018;57(1):52–56. doi: 10.1177/0009922817691821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraham O, Brothers A, Alexander DS, Carpenter DM. Pediatric medication use experiences and patient counseling in community pharmacies: Perspectives of children and parents. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(1):e32, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Twigg MJ, Bhattacharya D, Clark A, et al. What do patients need to know? A study to assess patients’ satisfaction with information about medicines. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(4):229–236. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mamen AV, Håkonsen H, Kjome RL, Gustavsen-Krabbesund B, Toverud EL. Norwegian elderly patients’ need for drug information and attitudes towards medication use reviews in community pharmacies. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015;23(6):423–428. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi ZM, Zhi XJ, Yang L, et al. Identify practice gaps in medication education through surveys to patients and physicians. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1423–1430. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S93219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazaryan I, Sevikyan A. Patients in need of medicine information. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2015;27(Suppl 1):S21–S22. doi: 10.3233/JRS-150675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahler C, Jank S, Hermann K, Haefeli WE, Szecsenyi J. Information zur Medikation – wie bewerten chronisch kranke Patienten das Medikationsgespräch in der Arztpraxis? [Information on medications – How do chronically ill patients assess counselling on drugs in general practice?] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2009;134(33):1620–1624. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1233990. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho CH, Ko Y, Tan ML. Patient needs and sources of drug information in Singapore: is the Internet replacing former sources? Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(4):732–739. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newby DA, Hill SR, Barker BJ, Drew AK, Henry DA. Drug information for consumers: should it be disease or medication specific? Results of a community survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(6):564–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Geffen EC, Kruijtbosch M, Egberts AC, Heerdink ER, van Hulten R. Patients’ perceptions of information received at the start of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor treatment: implications for community pharmacy. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(4):642–649. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zwaenepoel L, Bilo R, De Boever W, et al. Desire for information about drugs: a survey of the need for information in psychiatric in-patients. Pharm World Sci. 2005;27(1):47–53. doi: 10.1007/s11096-005-4696-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamberts EJ, Bouvy ML, van Hulten RP. The role of the community pharmacist in fulfilling information needs of patients starting oral antidiabetics. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2010;6(4):354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair K, Dolovich L, Cassels A, et al. What patients want to know about their medications. Focus group study of patient and clinician perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:104–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raynor DK, Savage I, Knapp P, Henley J. We are the experts: people with asthma talk about their medicine information needs. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borgsteede SD, Karapinar-Çarkit F, Hoffmann E, Zoer J, van den Bemt PM. Information needs about medication according to patients discharged from a general hospital. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(1):22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziegler DK, Mosier MC, Buenaver M, Okuyemi K. How much information about adverse effects of medication do patients want from physicians? Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(5):706–713. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.5.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meredith C, Symonds P, Webster L, et al. Information needs of cancer patients in west Scotland: cross sectional survey of patients’ views. BMJ. 1996;313(7059):724–726. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Williams BR, Cipri CS, Wenger NS. Which providers should communicate which critical information about a new medication? Patient, pharmacist, and physician perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):462–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herber OR, Gies V, Schwappach D, Thürmann P, Wilm S. Patient information leaflets: informing or frightening? A focus group study exploring patients’ emotional reactions and subsequent behavior towards package leaflets of commonly prescribed medications in family practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnett GC, Charman SC, Sizer B, Murray PA. Information given to patients about adverse effects of radiotherapy: a survey of patients’ views. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2004;16(7):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarn DM, Wenger A, Good JS, Hoffing M, Scherger JE, Wenger NS. Do physicians communicate the adverse effects of medications that older patients want to hear? Drugs Ther Perspect. 2015;31(2):68–76. doi: 10.1007/s40267-014-0176-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirsh D, Clerehan R, Staples M, Osborne RH, Buchbinder R. Patient assessment of medication information leaflets and validation of the Evaluative Linguistic Framework (ELF) Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berry DC, Knapp P, Raynor DK. Provision of information about drug side-effects to patients. Lancet. 2002;359(9309):853–854. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07923-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Büchter RB, Fechtelpeter D, Knelangen M, Ehrlich M, Waltering A. Words or numbers? Communicating risk of adverse effects in written consumer health information: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:76. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laaksonen R, Duggan C, Bates I. Desire for information about drugs: relationships with patients’ characteristics and adverse effects. Pharm World Sci. 2002;24(5):205–210. doi: 10.1023/a:1020542502118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamrosi KK, Raynor DK, Aslani P. Pharmacist and general practitioner ambivalence about providing written medicine information to patients-a qualitative study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(5):517–530. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGrath JM. Physicians’ perspectives on communicating prescription drug information. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(6):731–745. doi: 10.1177/104973299129122243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamb GC, Green SS, Heron J. Can physicians warn patients of potential side effects without fear of causing those side effects? Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(23):2753–2756. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420230150018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krag A, Nielsen HS, Norup M, Madsen SM, Rossel P. Research report: do general practitioners tell their patients about side effects to common treatments? Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(8):1677–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liseckiene I, Liubarskiene Z, Jacobsen R, Valius L, Norup M. Do family practitioners in Lithuania inform their patients about adverse effects of common medications? J Med Ethics. 2008;34(3):137–140. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.019448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krska J, Morecroft CW, Poole H, Rowe PH. Issues potentially affecting quality of life arising from long-term medicines use: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(6):1161–1169. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9841-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mutebi A, Warholak TL, Hines LE, Plummer R, Malone DC. Assessing patients’ information needs regarding drug-drug interactions. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53(1):39–45. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mody SK, Haunschild C, Farala JP, Honerkamp-Smith G, Hur V, Kansal L. An educational intervention on drug interactions and contraceptive options for epilepsy patients: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2016;93(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young A, Tordoff J, Smith A. “What do patients want?” Tailoring medicines information to meet patients’ needs. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(6):1186–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Indermitte J, Reber D, Beutler M, Bruppacher R, Hersberger KE. Prevalence and patient awareness of selected potential drug interactions with self-medication. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32(2):149–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dohle S, Dawson IG. Putting knowledge into practice: Does information on adverse drug interactions influence people’s dosing behaviour? Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(2):330–344. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Waters EA, Weinstein ND, Colditz GA, Emmons K. Explanations for side effect aversion in preventive medical treatment decisions. Health Psychol. 2009;28(2):201–209. doi: 10.1037/a0013608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myers ED, Calvert EJ. Information, compliance and side-effects: a study of patients on antidepressant medication. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;17(1):21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb04993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Howland JS, Baker MG, Poe T. Does patient education cause side effects? A controlled trial. J Fam Pract. 1990;31(1):62–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adam TJ, Vang J. Content and Usability Evaluation of Patient Oriented Drug-Drug Interaction Websites. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2015;2015:287–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gustafsson J, Kälvemark S, Nilsson G, Nilsson JL. Patient information leaflets – patients’ comprehension of information about interactions and contraindications. Pharm World Sci. 2005;27(1):35–40. doi: 10.1007/s11096-005-1413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wali H, Grindrod K. Don’t assume the patient understands: Qualitative analysis of the challenges low health literate patients face in the pharmacy. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(6):885–892. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]