Abstract

The environmental, socioeconomic and cultural significance of glaciers has motivated several countries to regulate activities on glaciers and glacierized surroundings. However, laws written to specifically protect mountain glaciers have only recently been considered within national political agendas. Glacier Protection Laws (GPLs) originate in countries where mining has damaged glaciers and have been adopted with the aim of protecting the cryosphere from harmful activities. Here, we analyze GPLs in Argentina (approved) and Chile (under discussion) to identify potential environmental conflicts arising from law restrictions and omissions. We conclude that GPLs overlook the dynamics of glaciers and could prevent or delay actions needed to mitigate glacial hazards (e.g. artificial drainage of glacial lakes) thus placing populations at risk. Furthermore, GPL restrictions could hinder strategies (e.g. use of glacial lakes as reservoirs) to mitigate adverse impacts of climate change. Arguably, more flexible GPLs are needed to protect us from the changing cryosphere.

Keywords: Andes, Glacial hazards, Glacier protection laws, GLOF, Mining

Introduction

The environmental and socioeconomic significance of glaciers is widely recognized (Scott et al. 2007; Pelto 2011). Glaciers provide vital ecosystem services (e.g. water storage and runoff regulation) and their fluctuations represent clear visual indicators of climate change (Houghton et al. 2001). Glacierized environments also attract tourists, generating millions of dollars in revenue worldwide (Scott et al. 2007; Purdie 2013) and represent economic assets benefitting the agriculture and hydropower sectors (Pelto 2011). Furthermore, glaciers have powerful symbolic and cultural value (Carey 2008; Bolin 2009); indeed, some mountain communities believe that glaciers are the abode of deities (Allison 2015). The recognition of the environmental, socioeconomic and cultural significance of glaciers has motivated governments from countries such as Argentina, Chile, and Kyrgyzstan to enact or discuss Glacier Protection Laws (GPLs) to protect glaciers from potentially damaging activities (Taillant 2015; Cox 2016).

Despite their socioeconomic and environmental significance, glacierized areas are also associated with a number of damaging geomorphic and hydrologic processes (e.g. Haeberli and Whiteman 2014). Sudden and/or gradual changes in glacier dynamics, for example, may trigger hazardous phenomena, such as Glacier Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) that can damage areas located hundreds of kilometres downstream, and ice avalanches (Petrakov et al. 2008). Socioeconomic damage caused by glacier processes has been recognized in several glacierized mountains worldwide (Carrivick and Tweed 2016). In Perú alone, rock-ice avalanches and GLOFs have caused more than 10 000 casualties in the 20th Century (Reynolds 1992; Carey 2005; Evans et al. 2009). Thus, several measures to reduce glacial hazards have been taken worldwide. In some cases, ice-dammed lakes have been drained using siphons and explosives (Vincent et al. 2010), whilst in others, ice has been mechanically removed from glaciers to avoid the risk of ice-falls or damage from glacier movement (Colgan and Arenson 2013). These measures have reduced the hazards posed by glaciers and glacial lakes to downstream communities, hydropower plants, and mining projects. However, where such interventions have directly involved interference with a glacier it has also changed the natural dynamics of the glacier involved.

In 2014, a law to protect glaciers and periglacial environments was enacted in Argentina and similar laws have been discussed in the Chilean and Kyrgyzstan parliaments. These GPLs are largely designed to protect glacierized environments from mining and other natural resource extraction activities that have the potential to destroy glacial ice, contaminate water supplies, threaten the cultural value of mountainous areas, discourage tourism, and impinge upon the aesthetic appeal of high-mountain landscapes. However, by restricting activities on and around glaciers, GPLs may also restrict or even prevent the timely implementation of glacial hazard mitigation. In this paper, we describe cases where glacier intervention could be required to manage glacial hazards (“Glacial hazards and the need for glacier intervention” section), analyze the historical development of GPLs in Argentina and Chile (“Outline of Glacier Protection Laws” section), provide examples of legal and environmental conflicts that could arise when managing glacial hazards in the current legal framework (“Anticipating legal and environmental conflicts managing glacial hazards and facing climate change effects” section), and finally make recommendations to be considered within GPLs to protect glaciers without putting people at risk or inhibiting certain climate change adaption strategies (“Conclusions and recommendations” section). Our work adopts environmental/glaciological point of view and do not intend to provide an in-depth analysis of GPLs from a legal perspective. However, advice was sought to assure that the legal context was correctly represented.

Glacial hazards and the need for glacier intervention

In the Central Argentinean and Chilean Andes, socioeconomic damage produced by glaciers has mostly been linked with episodic glacier advance, the hydrological impacts of blockage of mountain streams, and the growth and failure of ice-dammed lakes (Iribarren Anacona et al. 2015). Surging glaciers have been responsible for the majority of these events and multiple glacier surges have occurred nearly simultaneously in the extratropical Andes indicating a probable climate-driven phenomenon (Fig. 1). The best known example of a damaging surge event and outburst flood occurred in 1934 in the Argentinean Andes after the advance of Grande del Nevado del Plomo Glacier (La Vanguardia 1934). The outburst flood was generated when the advancing glacier blocked a stream, creating an ice-dam, which then failed due to the build-up of hydrostatic pressure. The flood caused 20 casualties and severe economic loses along the Mendoza Valley (Iribarren Anacona et al. 2015). Surging glaciers can be particularly dangerous since after surging, highly crevassed glacier snouts can become stranded at lower, warmer altitudes and can form ice dams that block rivers. These ice dams can be rapidly weakened by melting, thereby increasing the likelihood of catastrophic flooding. Thus, actions to reduce the outburst flood hazard or the burial of infrastructure by advancing glaciers can be required over a timescale as short as months or even weeks, making delays due to the requirement to complete a detailed EIS potentially dangerous.

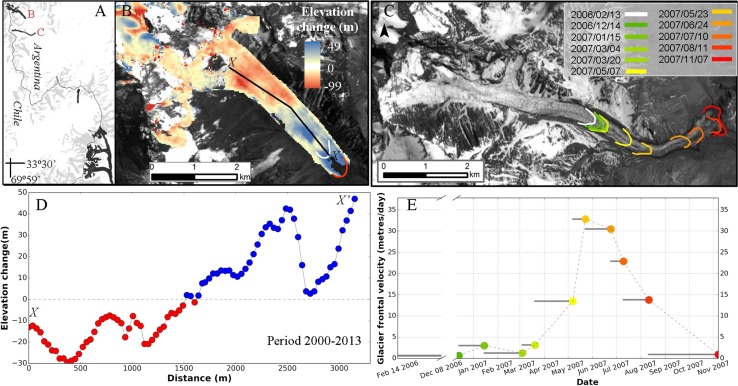

Fig. 1.

a Advancing and surging glaciers (in black) in the Central Chilean and Argentinean Andes during the period of 2004–2007. Examples of glacier mass relocation and frontal progress is shown in the panels b–e. Between March and November of 2007, Grande del Nevado del Plomo Glacier advanced ~ 3 km with a maximum velocity of ~ 33 m/day (e). If an ice dam is formed in a future surge, potentially controversial methods, such as blasting, could be used to open a channel in the ice dam. Elevation change derived from SRTM and TanDem-X digital elevation models (DEM). DEMs were co-registered following Nuth and Kääb (2011) before elevation change estimation

In Patagonia, glaciers are responding rapidly to climate change and have, in general, retreated and thinned considerably over recent decades (Davies and Glasser 2012; Paul and Mölg 2014). This glacial retreat has resulted in the formation and growth of a large number of glacial lakes (Loriaux and Casassa 2013). Some of these lakes have achieved large areas and have subsequently failed producing voluminous (> 106 m3) outburst floods (Harrison et al. 2006; Iribarren Anacona et al. 2015; Fig. 2). The surface area of glacial lakes can remain unchanged, grow steadily over decades or, in some instances, undergo large changes over short periods of time (months to years) as a result of large calving events amongst other factors. The latter scenario can result in the rapid increase in the volume of water available for outburst floods, highlighting the need for continuous monitoring programmes and the facility to implement rapid interventions to prevent GLOFs. Unfortunately, these scenarios have not been taken into account in GPLs.

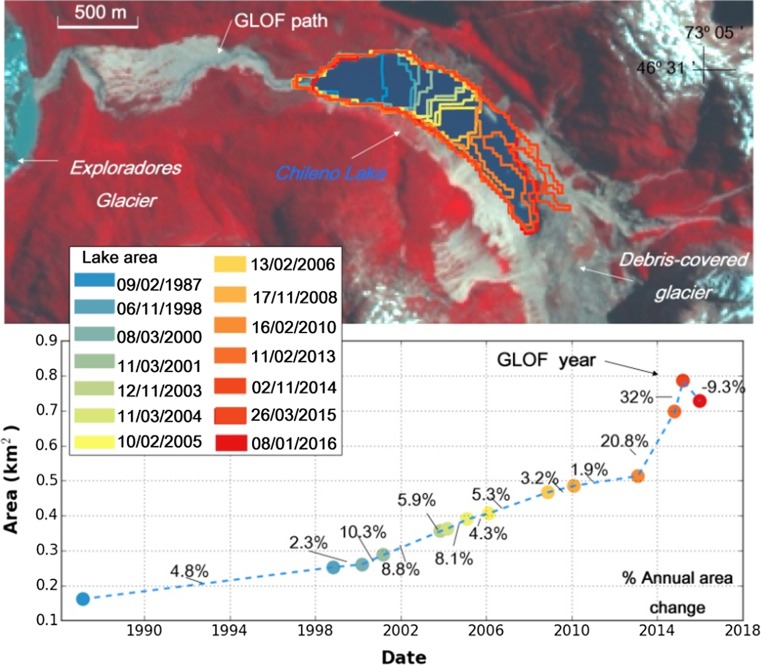

Fig. 2.

Accelerated growth of a moraine-dammed lake in Valle de los Chilenos, Chilean Patagonia. Note the exponential area increase (more than 30% in 1 year) prior to the 2015 GLOF. Rapid lake changes highlight the need for quick hazard management responses, which could include siphoning of glacial lakes in National Parks and/or pristine landscapes

Outline of Glacier Protection Laws

In a number of places, regulations restrict activities undertaken on glaciers and glacier surroundings. In Antarctic for example, the Antarctic Treaty System strictly regulates the waste disposal in the continent and prohibit the exploitation of mineral resources (Butler 2007). In countries such as Canada and Ecuador, activities developed on glaciers and surrounding areas are regulated by National Parks, although commonly there is no explicit mention to glaciers in the legislation (Iza and Rovere 2006; Cox 2016). Regulations affecting glacierized areas can vary intranationally specially in federal states. However, the Civil Code of several countries considers water in their different states as a public property of common use (Iza and Rovere 2006; Butler 2007). Specific regulations regarding glaciers are rare. In Switzerland, for example, according to the decree about concessions for mountain railways and cable cars, cable cars can be developed only on glaciers located close to major tourist villages when glaciers ensure a prolonged ski season (Butler 2007).Thus, glacier legislation is usually embedded into environmental laws, water management protocols and regional planning strategies (Cox 2016). National laws written specifically to regulate or protect mountain glaciers have only recently been adopted and/or considered in national political agendas. These laws were motivated by environmental conflicts arising from mining operations developed on ice-capped mountains (Kronenberg 2013; Taillant 2015; Fig. 3). Thus, mountainous countries such as Argentina, Chile, and Kyrgyzstan, whose economies are largely sustained by mining in glacierized ranges, have led the development of GPLs (Table 1). Indeed, the proposed Kyrgyzstan GPL resembles (in aims and structure) the approved Argentinean law reflecting that both laws were drafted to face similar environmental, political and socioeconomic conflicts. The following section summarizes the historical development of GPLs in Chile and Argentina and highlights legal restrictions and omissions that may constrain glacier management practices and hamper strategies aimed at mitigating impacts of climate change.

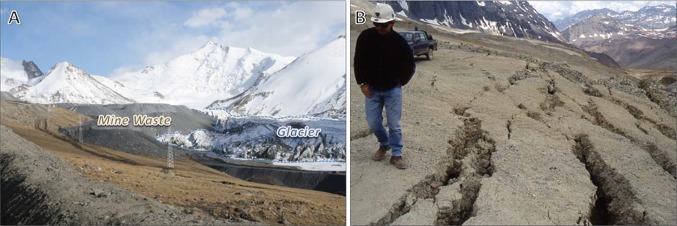

Fig. 3.

a Mine waste dumped on the margin of the Davidoff Glacier at Kumtor Mine, Kyrgyzstan, causing deflected and accelerated flow of the glacier in response to the additional loading from the mine waste. b Example of cracking caused by ice creep affecting a haul road constructed over a mine-waste-/debris-covered glacier at a copper mine in the Central Andes, Chile

Table 1.

Description of GPLs status and jurisdiction

| Country | What is protected | Mention of glacial hazards | Law status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina Law 26.639 (2010) |

Glaciers and permafrost (i.e. frozen or ice-saturated ground) | Allows for the construction of infrastructure to prevent risks (subject to Environmental Impact Statements (EIS)). Article 6b | Approved |

| Chile Law submitted May 2016 |

Glaciers, glacierized catchments, and areas 1000 metres downstream from glacier fronts | No | Third version of the law under discussion in parliament since 2016 |

| Kyrgyzstan (2014) |

Glaciers, zones of continuous permafrost and snowfields (snow that remains after the disappearance of seasonal snow) | No | Approved by parliament in 2014 and vetoed by president |

Historical development of glacier protection laws: Stakeholders and socioeconomic interests

Politics plays a major role in protecting the natural environment and possibly has a larger influence on current GPLs than scientific evidence (Taillant 2015). Argentina was the first country to enact an official law protecting the country’s glaciers, which was promulgated on September 30, 2010 (Table 1). Yet, like in Chile, the enactment of the law had a political backlash. The first draft of the law passed Congress in 2008, only to be vetoed by then-President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who argued that the law would have an adverse economic effect on the country by obstructing the mining industry (Fernandez and Massa 2008). Indeed, in 2008, mining exports totalled over $12 billion annually—making it one of Argentina’s biggest international trade sectors and sources for domestic employment (Younker 2010).

In Chile, a GPL has not yet been adopted; however, a draft law was proposed in 2006 (Horvath 2006) and at least three revised versions have been proposed since (Table 2). The first of these laws was drafted in response to the Pascua Lama mining project which proposed to remove glacier ice for the excavation of mining materials. The proposed actions of the Pascua Lama mining project proved to be highly controversial, and subsequent political demonstrations put pressure on the government to take action to protect glaciers. Indeed, following this controversy, Greenpeace declared Chile’s glaciers an independent country on March 5, 2014, naming it the Glacier Republic—a move seen as a symbolic act of dissent rather than a true legal battle over national borders (Urquieta 2014). The Chilean government, however, has a strong vested interest in the mining industry and faced a strong backlash from stakeholders of the mining sector (Taillant 2015).

Table 2.

Contents of the Chilean and Argentinean laws

| Articles of proposed Chilean law | Articles of approved Argentinean law |

|---|---|

| 1. Aims (protect glaciers as water reserves and providers of ecosystem services) 2. Definition of glaciers and related terms 3. Glacier types recognized by law 4. Glacier’s legal nature 5. Definition of strategic glaciers 6. Forbidden activities 7. Description of activities that require EIS 8. Description of activities that require special authorization 9. Creation of a national register of glaciers 10. Water Directorate assessment of activities that could affect glacier dynamics 11. Issuing of Water Directorate permits 12. Revocation of past permits to intervene glaciers and surrounding areas 13. Modifications of the Water Code 14. Modifications of the Environmental Law 15. Modifications of the Environmental Tribunal Law |

1. Aims (protect glaciers and the periglacial environment as water sources) 2. Definition of glacier and periglacial environment 3. Creation of a national glacier inventory 4. Data included in the glacier inventory 5. Institution responsible of the glacier inventory 6. Forbidden activities 7. Description of activities that require EIS 8. Competent authorities 9. Authority in charge of applying the law 10. Authority’s role 11. Offences and sanctions 12. Penalties for recidivism 13. Offender responsibilities 14. Destiny of resources collected through fines 15. Deadlines to develop a glacier inventory 16. The Antarctic law (operates international laws signed by Argentina) 17. Deadlines to law implementation 18. Communication of the law to the executive |

Although mining has covered, removed, or disturbed millions of cubic metres of glacier ice in the Mapocho and Aconcagua basins in the Chilean Andes (Brenning 2008), the government has a strong interest in keeping the mines open since mining is the principal sector of the Chilean economy. Codelco, a state owned and operated copper mining company which has damaged glacierized areas in the Central Chilean Andes (Brenning 2008), for example, has generated 55.1 billion USD between 2004 and 2011 (before tax) and employed 63 311 people (Codelco 2011). Highlighting its importance, the Chilean government invested 600 million USD into Codelco in 2015, following the international price crash of metals, to help expand mining efforts (Ministerio de Hacienda 2015). That same year, a revised draft of the GPL was proposed by the Minister of the Environment, Pablo Badenier, was amended by parliament in May 2016, and is still under consideration.

Reactions to the proposed Chilean GPL vary widely. For example, documents published by the Chilean government state that the law would “Guarantee the protection of all Chilean glaciers” (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente 2015) while activist organizations such as Observatorio Latinoamericano de Conflictos Ambientales (OLCA) claim that the original GPL proposal has been reviewed and weakened three times due to pressure from the mining industry, including Codelco (Olca 2016). The 2015 draft was even strongly criticized by the Chilean Supreme Court, who argued that the document does not guarantee adequate protection of all glaciers from potentially harmful activities and thus the law could transgress the principle of non-regression in environmental law (Poder Judicial 2016).

Importantly, although GPLs in Chile and Argentina have been developed with the aim of protecting water resources, (mainly in response to extractive mining activities), issues such as glacial hazards and changes in the periglacial landscape in response to climate change have not been properly addressed. Such omissions have the potential to limit the impact of GPLs, transforming them into static instruments that could be obsolete in a short period due to the challenges that a changing glacial landscape (e.g. rapidly advancing or retreating glaciers and the formation of glacial lakes) pose for mountain communities.

Glacier protection laws and management of glacial hazards

GPLs have overlooked glacial hazards and the potential need to intervene with glacial landscapes to adapt to the effects of climate change. In Argentina, for example, glacial hazards are minimally addressed in the wording of their enacted GPL. Article 6 of the Argentinean GPL defines prohibited activities that include those “which may affect a glacier’s natural condition or functions described in article 1, and those activities which may destruct, move or alter glacier advance”. Article 6b goes into greater specificity by prohibiting “the construction of infrastructure except those necessary for scientific research and preventing risks” (bold font added for emphasis). Hence, GLOFs and other glacial hazards would fall under this section of the law, allowing modification of the periglacial environment to prevent potential risks. However, it does not specify which actions are allowed or explicitly prohibited and does not define the potential risks. Instead, an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) would likely be required on a case-by-case basis because “any activity to be developed on a glacier or the periglacial belt, which is not forbidden, will be subject to an EIS and to an Environmental Strategic Assessment,” as stated in Article 7. The only case in which an EIS would not be required would be if the glacial hazard could be categorized as an emergency rescue as defined in article 7a: where it states that EISs “are exempted from this requirement…rescue activities due to emergencies”. In this regard, the intervention of glacial landscapes to prevent outburst floods or other hazards would likely be prohibited unless an EIS is provided. Activities that require an EIS are discussed in Article 7 and include anything that “can affect glaciers directly or indirectly” thus geoengineering methods commonly used to drain glacial lakes would be subject to an EIS. However, there is some room for interpretation in Article 8c where it states that “rescues derived from aerial or terrestrial emergencies” require special authorization. If loosely interpreted, interfering in the glacial landscape to prevent a GLOF could be categorized as an emergency rescue mission because it would result in the saving of lives and the protection of infrastructure, which would circumvent the need for an EIS.

In Chile, Article 6 of the proposed GPL addresses prohibited activities that include “any infrastructure, programme or activity of commercial purposes developed on a glacier or glacier surroundings, if the glacier is located in a Virgin Reserve (public space with natural conditions excluded from commercial use) or a National Park”. Hence, since hazard prevention is not a commercial activity, it falls outside of this restriction. Yet it should be noted that this only applies to only around 43% of Chilean glaciers (those existing within Virgin Reserves, National Reserves and/or National Parks), most of which are located in sparsely populated regions of Patagonia (Segovia Rocha 2015). On glaciers declared as Strategic Reserves (“glaciers whose melt discharge contributes significantly to basin runoff”), “digging, moving, destructing or covering glaciers with waste material, which could accelerate glacier melting, is forbidden.” This could provide room for the law to be misinterpreted since covering glaciers with thick and low thermal conductivity waste material may protect glaciers from melting (although altering the water chemistry and glacier flow characteristics, such as at Kumtor Mine, Kyrgyzstan (Kronenberg 2013)). “Likewise, it is forbidden to develop any infrastructure or activity on the glacier surroundings which can alter the glacier in a significant way”.

The Argentinean GPL regulates activities on glaciers and their surrounding areas using open clauses but specify some allowed and forbidden actions. These restrictions apply to all the Argentinean glaciers. The Chilean GPL also uses open clauses to regulate activities in glacierized areas, however, Article 7 does not clarify if these regulations apply to all glaciers or to glaciers previously protected by a public authority (i.e. glaciers declared Strategic Reserves or glaciers located in National Parks or Virgin Reserves)”. Thus, under the proposed GPL, the administrative procedures to intervene a glacier in case of an emergency will differ according to the protection category of each glacier.

The wording of the GPL in both Argentina and Chile is similar and glosses over the need for a protocol regarding how to handle GLOFs and other glacial and permafrost (e.g. rock falls from rock glaciers or ice-saturated ground)-related hazards. In the current legal context, the most likely scenario for handling a hazard would be to conduct an EIS, yet this procedure may take months or even years (Miningpress 2015), during which time the hazard could put lives and infrastructure in danger. Notably, under special circumstances (such as in “public calamities”) the Chilean environmental law can reduce in half the time needed for an EIS (Supreme Decree Nº 40). To avoid excessive delays, the hazard could also be categorized as a rescue mission under the article 7 of the Argentinean law and article 8 of the proposed Chilean law; however, this is subject to law interpretation. It is worth noting that in both Argentina and Chile, public works can be developed in National Parks if the infrastructure is of national interest. This may open the room for glacial hazard mitigation measures. This is significant since 14 of 38 failed lakes in Patagonia and Central Andes (see Wilson et al. 2018) were located in National Parks or Virgin reserves and that the devastating (five casualties and 15 people missing; Vera 2017) rock-slide (sourced from a recently deglaciated area) and subsequent hyper-concentrated flow that affected Villa Santa Lucía in December 2017 initiated in a National Park.

Although the proposed (Chile) and enacted (Argentina) GPLs define the institutions in charge of monitoring and inventorying glaciers, they do not specifically define which institutions are in charge of identifying glacial hazards. This could be a drawback since well-defined institutional roles are a key in glacial hazard management (Carey 2008). Indeed, ill-defined roles could cause liability issues in case of damage produced by hazardous processes sourced from glacier and permafrost areas (Cox 2016).

Glacier protection laws and adaptation to climate change

A further drawback of the GPLs discussed is that they may unintentionally hinder climate change adaptation by prohibiting any interference in glacial landscapes. As previously stated, GPLs were drafted primarily to stop potentially harmful mining practices. However, in doing so, they unintentionally restrict local communities from altering the glacial landscape for adaptation purposes. In other words, there is no distinction between community use of glacierized environments (including periglacial areas and glacial lakes) and commercial use (e.g. mining) even though the tangible effects of each are very different. With decreasing rainfall and increasing temperatures in Andean regions (e.g. Vicuña et al. 2011; Vuille et al. 2015), it may be in the best interest of local communities to use glacial lakes, for example, as reservoirs for drinking water or for subsistence agriculture since demand for irrigation water is expected to increase due to global warming (Meza et al. 2012). In fact, synergies between multipurpose projects of flood prevention, hydropower generation and water regulation for agriculture in glacierized basins have been proposed in the Alps and Cordillera Blanca (Haeberli et al. 2016). Yet all modifications of glaciers (and thus some glacial lakes) for economic benefits are outlawed under the GPLs. However, Chile’s law states in Article 4 that, “Glaciers are national goods of public use”. Consequently, glaciers are not subject to appropriation. Furthermore, “glaciers cannot be tradable as water resources”. Defined as such, glaciers and their waters are property of the public and should serve the community needs. Similarly, Argentina states that the objective of their GPL is to “preserve glaciers as strategic water reserves for human consumption, for agriculture and for basin recharge, for maintaining the biodiversity, as a source of scientific data and as a tourist attraction”. Thus, there is a potential conflict within the wording of GPLs by defining glaciers as public goods while also prohibiting local communities from modifying them to best serve their needs in adapting to climate change. As an example, the Chilean GPL mentions that englacial, supraglacial and subglacial water bodies are parts of glaciers and that glaciers cannot be traded in the water market. Thus, the use of some glacial lakes for economic purposes is forbidden (especially lakes in contact with glaciers). However, the Chilean Water Code mentions that all terrestrial water bodies (i.e. lakes, rivers and wetlands) are tradable. In the current form, the Chilean GPL will tacitly derogate the Chilean Water Code limiting the use of glacial lakes.

Anticipating legal and environmental conflicts managing glacial hazards and facing climate change effects

As we have discussed, GPLs currently fail to recognize glacial and permafrost-related hazards. GPLs specify the activities that can be developed on glaciers and their surrounding landscapes (e.g. mountaineering, rescue missions and scientific expeditions), and the activities that are forbidden (e.g. removing glaciers from National Parks) or should be subject to an EIS. However, there is no specific regulation regarding preventive or emergency measures when dealing with glacial hazards. Moreover, there is no distinction between the modification of glaciers or their surrounding areas for mining or other potentially harmful activities and those made by communities responding to the effects of climate change. These omissions could result in social and environmental conflicts since interventions in the glacial landscape unavoidably change glacier and permafrost dynamics and may face cryoactivism opposition (e.g. Taillant 2016; Tollefson and Rodríguez Mega 2017). For example, the hazard posed by moraine-dammed lakes can be reduced through dam reinforcement techniques, which include dam reprofiling, impermeabilization and grouting (Portocarrero 2014). These techniques can modify the thermal and hydrological regime of ice-cored moraines. Lowering lake levels by tunnelling or siphoning, on the other hand, can modify ice flow dynamics by decreasing ice velocity and changing calving rates.

Other techniques, such as ice mechanical excavation, melting and blasting (Colgan and Arenson 2013), have been applied by engineering projects in high-mountain areas and can be used to prevent damage from glacier advance or to drain an ice-dammed lake (Vincent et al. 2010). These techniques will have a direct impact on glacier volume and dynamics (as a result of ice mass being removed) and could have an impact on the chemical composition of glaciers since explosives release debris and chemicals during blasting. Due to the impacts in the glacial and periglacial environment, a thorough communication to the public of glacial and permafrost-related hazards is required to avoid social pressure that could delay hazard reduction measures. As Carey (2008) suggests, people can influence not only their vulnerability to natural hazards but also can affect the implementation of hazard mitigation policies.

Conflicts can arise when managing the hazard posed by glacial lakes located in sensitive areas (e.g. Kargel et al. 2012), such as National Parks and/or pristine landscapes, which are common in Patagonia and in arid regions where competition for water resources is intense (Taillant 2015; Fig. 4). Delays in the response to potentially hazardous lakes brought about by such conflicts could result in larger outburst floods increasing the risks posed to downstream communities and infrastructure. Furthermore, litigation issues could arise if an EIS is not developed quickly enough and damaging hazards are triggered. Despite conflicts specifically related to glacial hazards having not yet occurred in the extratropical Andes, they should be considered since one of the major challenges of climate change adaptation is facing hazardous processes in new places and with unprecedented intensity (IPCC 2014).

Fig. 4.

Ice-dammed lake at Río Seco de los Tronquitos Glacier in the arid Andes of Chile (January 2018). A lake on the same glacier produced a GLOF in 1985 that damaged agricultural land 100 km downstream. Due to the region’s water scarcity, modifying the glacier or the lake to prevent a future GLOF could result in environmental conflict

Several questions arise from the aforementioned conflicts regarding the implementation of GPLs. For example: what would happen if hazard reduction measures (that inevitably impact glaciers and/or frozen ground) are required promptly, in shorter timescales than those required to develop an EIS? What will happen if hazard reduction measures (e.g. the use of explosives or the removal of glacier ice) are seen as harmful to the environment and rejected by the community in EIS public consultations? What would happen if glaciers advance and the new protected area encompass sites already being exploited economically?

Conclusions and recommendations

GPLs have been drafted in Chile and Argentina with the aim of safeguarding glacierized areas from the negative effects of mining activity. However, in the proposed and implemented GPLs of both countries, provisions for physical interventions to mitigate and/or prevent glacial hazards and the effects of climate change have been mostly overlooked. In the current legal context, laws could delay or even prohibit hazard reduction measures, and in doing so, adversely affect downstream communities and socioeconomic assets and hamper climate change adaptation strategies. We argue that both laws were drafted with retreating and stagnant glaciers in mind, overlooking the possibility of glacier advance, rapid glacier retreats and concomitant challenges.

We suggest that GPLs should include exceptions that allow for timely interventions at glacier and permafrost sites of interest, to protect human life and/or strategic infrastructure. These exceptions could accelerate decision-making processes and will help avoiding future legal constraints when managing emergencies associated with glacial hazards. Thus, we argue that exceptions in GPLs should not only allow authorities to modify potentially threatening glaciers and ice-rich permafrost, such as rock glaciers, but also ensure that these interventions are allowed quickly in case of emergencies, which may imply shortening of the EIS process. GPLs should also clearly state which national and local institutions and authorities are in charge of identifying and managing glacial hazards to provide qualified personnel, equipment, and resources when needed.

Omissions in past and proposed GPLs can result in social and environmental conflicts. Such conflicts can arise when intervention is needed for glacial lakes in National Parks (e.g. constructing dam reinforcement infrastructure or siphoning of glacial lakes), for example, or when supraglacial or subglacial lakes need to be drained in arid regions where competition for water resources is high.

GPLs should be clear about the interventions allowed to protect economic projects already located in glacierized areas since allowing glacier intervention to manage glacial hazards can be used as a loophole to intervene in the glacial landscape for purely economic purposes (e.g. to protect mining facilities). Open clauses in GPLs instead of detailed lists of glacier interventions authorized could help to better manage glacial hazards choosing the best method according to ground conditions and the available resources.

Environmental conflicts associated with glaciers identified in the Chilean and Argentinean Andes could arise in other geographic settings since mountain glaciers are retreating globally and laws tend to overlook spatial heterogeneity and landscape dynamics (Bartel et al. 2013). Thus, the extratropical Andes offer a good example of potential environmental and legal conflicts that could arise as a result of glacial landscape intervention. Finally, we argue that GPLs should protect glaciers from harmful activities; however, GPLs also should ensure the right of communities to intervene with the glacial landscape to mitigate adverse climate change effects. This requires a throughout socio-ecologic cost–benefit analysis where all relevant environmental benefits and costs are carefully weighted.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the RCUK-CONICYT project MR-N026462-1 “Glacial Hazards in Chile: Processes, Assessment, Mitigation, and Risk Management Strategies” and a VRIEA-PUCV project. This study was kindly supported with TanDEM-X data under DLR AO XTI_GLAC0264. David Farías acknowledge the support of Becas Chile, CONICYT. We thank Mark Carey and Alejandra Mancilla for commenting on an early draft of this work. We also thank two reviewers whose comments helped to strengthen our text.

Biographies

Pablo Iribarren Anacona

is Lecturer at the Universidad Austral de Chile/Instituto de Ciencias de la Tierra. His research interests include glacial and permafrost-related hazards and mountain geography.

Josie Kinney

is a recent graduate of the University of Oregon Robert D. Clark Honors College with a bachelors in environmental studies and Spanish. Her research interests include political ecology and, more broadly, the ways in which capitalism, climate change, and politics intersect to create—or resolve—environmental justice issues.

Marius Schaefer

is Assistant Professor at Universidad Austral de Chile/Instituto de Ciencias Físicas y Matemáticas. His research interests include Glaciology, Glacier-Climate Interactions, Geophysical Flows, Calving Glaciers and Glacial Hazards.

Stephan Harrison

is a climate scientist working on climate change impacts, natural hazards and climate change adaptation in the world’s mountains. He has worked for over 30 years on earth system responses to climate change in Patagonia, and also in the tropical Andes, Himalaya, Tien Shan and European Alps. From this research, Stephan has published over 150 refereed scientific papers. He is a former Leverhulme Research Fellow and is a climate change advisor to the UK Government.

Ryan Wilson

is Post-Doctorate Research Associate at Aberystwyth University working on the NERC/CONICYT funded ‘Glacial Hazards in Chile Project’. Ryan’s research interests are centred on the application of GIS and remote sensing datasets to monitor and map the cryosphere. These interests are aimed at achieving a better understanding of past, present and future glacier change and its subsequent impacts on the environment.

Alexis Segovia

is a geographer and master in “Conservation of Nature and Wilderness Areas” of the University of Chile. His research interests include mountain ecosystems, environmental policy, ecological economics and ecosystem services.

Bruno Mazzorana

is Associate Professor at the Universidad Austral de Chile/Instituto de Ciencias de la Tierra. His research interests include Natural Hazard related Risks, Fluvial Dynamics and Adaptive Capacity of SETS (social, ecological and technological systems).

Felipe Guerra

is a Lawyer and Researcher at Observatorio Ciudadano. His research interests include Environmental Law and Regulation of Natural Resources, as well as Human Rights of Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples.

David Farías

is a Ph.D. student at the Glaciology and Remote Sensing group, Institute of Geography, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany.

John M. Reynolds

is an Honorary Professor, Aberystwyth University, Wales, UK, and Managing Director of Reynolds International Ltd, his own geological and geophysical consultancy company based in Mold, Wales, UK. His professional and research interests include integrated geohazard assessment, glacial hazards, and geohazard mitigation, especially in the Andes and Hindu Kush–Karakoram–Himalayas.

Neil F. Glasser

is a Professor of Physical Geography at Aberystwyth University in Wales. His research interests include the effects of climate change on glaciers in South America, Himalayan glaciology and water resources, and the response of the Antarctic Ice Sheet and its ice shelves and glaciers to recent climate change.

Contributor Information

Pablo Iribarren Anacona, Email: pablo.iribarren@uach.cl.

Josie Kinney, Email: Josie11k@gmail.com.

Marius Schaefer, Email: mschaefer@uach.cl.

Stephan Harrison, Email: stephan.harrison@exeter.ac.uk.

Ryan Wilson, Email: ryw3@aber.ac.uk.

Alexis Segovia, Email: alexisegov@ug.uchile.cl.

Bruno Mazzorana, Email: bruno.mazzorana@uach.cl.

Felipe Guerra, Email: felipe.guerra.schleef@gmail.com.

David Farías, Email: david.farias@fau.de.

John M. Reynolds, Email: jmr@reynolds-initernational.co.uk

Neil F. Glasser, Email: nfg@aber.ac.uk

References

- Allison E. The spiritual significance of glaciers in an age of climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 2015;6:493–508. doi: 10.1002/wcc.354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel R, Graham N, Jackson S, Prior JH, Robinson DF, Sherval M, Williams S. Legal geography: An Australian perspective. Geographical Research. 2013;51:339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin I. The glaciers of the Andes are melting: Indigenous and anthropological knowledge merge in restoring water resources. In: Crate SA, Nuttall M, editors. Anthropology and climate change: From encounters to actions. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2009. pp. 228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Brenning A. The impact of mining on rock glaciers and glaciers. Examples from central Chile. In: Orlove BS, Wiegandt E, Luckman B, editors. Darkening peaks: Glacier retreat, science, and society. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008. pp. 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, M. 2007. Glaciers as objects of law and international treaties. In Alpine space-man & environment, ed. Psenner, R. and Lackner, R. vol. 3, The water balance of the Alps, What do we need to protect the water resources of the Alps? Proceedings of the Conference held at Innsbruck University, 28–29 September 2006. Innsbruck: Universidad de Innsbruck, 2007, 19–31 pp.

- Carey M. Living and dying with glaciers: People’s historical vulnerability to avalanches and outburst floods in Peru. Global and Planetary Change. 2005;47:122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey M. The politics of place: Inhabiting and defending glacier hazard zones in peru’s Cordillera Blanca. In: Orlove B, Wiegandt E, Luckman B, editors. Darkening peaks: Glacial retreat, science, and society. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008. pp. 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Carrivick J, Tweed F. A global assessment of the societal impacts of glacier outburst floods. Global and Planetary Change. 2016;144:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codelco. 2011. History of Codelco. Retrieved August 5, 2016, from https://www.codelco.com/flipbook/memorias/memoria2011/en/history.html.

- Colgan W, Arenson L. Open-pit glacier ice excavation: Brief review. Journal of Cold Regions Engineering. 2013;27:223–243. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CR.1943-5495.0000057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. Finding a place for glaciers within environmental law: An analysis of ambiguous legislation and impractical common law. Appeal. 2016;21:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Davies B, Glasser N. Accelerating recession in Patagonian glaciers from the “Little Ice Age” (c. AD 1870) to 2011. Journal of Glaciology. 2012;58:1063–1084. doi: 10.3189/2012JoG12J026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Bishop N, Smoll L, Murillo P, Delaney K, Oliver-Smith A. A re-examination of the mechanism and human impact of catastrophic mass flows originating on Nevado Huascarán, Cordillera Blanca, Peru in 1962 and 1970. Engineering Geology. 2009;108:96–118. doi: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2009.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, C., and S. Massa. 2008. Obsérvase El Proyecto De Ley Registrado Bajo El N 26.418. Dirección Nacional del Registro Oficial Decreto 1837. 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2016, from http://www.bdlaw.com/assets/htmldocuments/CHILE_Argentine_Presidential_Veto_(Decree_1837_2008).PDF.

- Haeberli W, Whiteman C, editors. Snow and ice-related hazards, risks, and disasters. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haeberli W, Bütler M, Huggel C, Lehmann T, Schaub Y, Schleiss A. New lakes in deglaciating high-mountain regions—Opportunities and risks. Climatic change. 2016;139:201–214. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1771-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S, Glasser N, Winchester V, Haresign E, Warren CR, Jansson K. A glacial lake outburst flood associated with recent mountain glacier retreat. Patagonian Andes, Holocene. 2006;16:611–620. doi: 10.1191/0959683606hl957rr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, A. 2006. Proyecto de ley sobre valoración y protección de los glaciares. Senado de Chile, 9 p.

- Houghton JT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ, Noguer M, van der Linden PJ, Dai X, Maskell K, Johnson CA, editors. Climate change 2001: The scientific basis: Contribution of working group 1 to the Third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, 881 pages. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC Climate Change. 2014. Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Summary for policymakers. In Contribution of working group II to the intergovernmental panel on climate change ed. Field, C.B. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Iribarren Anacona P, Mackintosh A, Norton KP. Hazardous processes and events from glacier and permafrost areas: Lessons from the Chilean and Argentinean Andes. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 2015;40(1):2–21. doi: 10.1002/esp.3524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iza, A., and M.B.Rovere. 2006. Aspectos jurídicos de la conservación de los glaciares. UICN, Gland, Suiza. ISBN-10: 2-8317-0921-0.

- Kargel JS, Alho P, Buytaert W, Celleri R, Cogley JG, Dussaillant A, Zambrano G, Haeberli W, et al. Glaciers in Patagonia: Controversy and prospects. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 2012;93:212. doi: 10.1029/2012EO220011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg J. Linking ecological economics and political ecology to study mining, glaciers and global warming. Environmental Policy and Governance. 2013;23:75–90. doi: 10.1002/eet.1605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Vanguardia. 1934. El desbordamiento del Mendoza. Sábado 13 de Enero de 1934; 26–27 pp.

- Loriaux TH, Casassa G. Evolution of glacial lakes from the Northern Patagonian Icefield and terrestrial water storage in a sea-level rise context, Global Planet. Change. 2013;102:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Meza F, Wilks DS, Gurovich L, Bambach N. Impacts of climate change on irrigated agriculture in the Maipo Basin, Chile: Vulnerability of water rights and changes in the demand for irrigation. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management. 2012;138:421–430. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miningpress. 2015. SEIA: Cuánto demora la tramitación ambiental en Chile. Retrieved September 4, 2017, from http://www.miningpress.com/nota/290452/seia-cuanto-demora-la-tramitacion-ambiental-en-chile.

- Ministerio de Hacienda. 2015. Declaración pública sobre capitalización de codelco. Gobierno de Chile. 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2016, from http://www.hacienda.cl/sala-de-prensa/noticias/historico/declaracion-publica-sobre.html.

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile. 2015. Experto Del Cees Valora Aporte De La Ley Que Busca Proteger Los Glaciares. Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile. 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2016, from http://portal.mma.gob.cl/experto-del-cees-valora-aporte-de-la-ley-que-busca-proteger-los-glaciares/.

- Nuth C, Kääb A. Co-registration and bias corrections of satellite elevation data sets for quantifying glacier thickness change. The Cryosphere. 2011;5(271–290):2011. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio latinoamericano de conflictos ambientales (OLCA). 2016. Ante denuncias: Comisión de derechos humanos pide revisar proyecto de ley de “Protección” De Glaciares. Retrieved July 18, 2016, from http://olca.cl/articulo/nota.php?id=106140.

- Paul F, Mölg N. Hasty retreat of glaciers in northern Patagonia from 1985 to 2011. Journal of Glaciology. 2014;60(244):1033–1043. doi: 10.3189/2014JoG14J104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelto M. Hydropower: Hydroelectric power generation from alpine glacier melt. Encyclopaedia of Snow Ice and Glaciers. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011. pp. 546–551. [Google Scholar]

- Petrakov DA, Chernomorets SS, Evans SG, Tutubalina OV. Catastrophic glacial multi-phase mass movements: A special type of glacial hazard. Advances in Geosciences. 2008;14:211–218. doi: 10.5194/adgeo-14-211-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poder Judicial. 2016. Oficio No. 110-2016. Informe Proyecto de Ley No. 26-2016. 12 p.

- Portocarrero C. The glacial lake handbook. Reducing risk from dangerous glacial lakes in the Cordillera Blanca, Perú. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Agency for International development; 2014. p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Purdie H. Glacier retreat and tourism: Insights from New Zealand. Mountain Research and Development. 2013;33:463–472. doi: 10.1659/mrd-journal-d-12-00073.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JM. The identification and mitigation of glacier-related hazards: Examples from the Cordillera Blanca, Peru. In: McCall GJH, Laming DCJ, Scott S, editors. Geohazards. London: Chapman & Hall; 1992. pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia Rocha A. Glaciares en el Sistema de Áreas Silvestres Protegidas por el Estado (SNASPE) Investigaciones Geográficas, 2015;49:51–68. doi: 10.5354/0719-5370.2015.37513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D, Jones B, Konopek J. Implications of climate and environmental change for nature-based tourism in the Canadian Rocky Mountains: A case study of Waterton Lakes National Park. Tourism Management. 2007;28:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taillant J. Glaciers: The politics of ice. USA: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- Taillant, J. 2016. Cryoactivism. Environmental justice and climate change in Latin America, vol. xlvii: Issue 4.LASA FORUM.

- Tollefson J, Rodríguez Mega E. Argentinean geoscientist faces criminal charges over glacier survey. Nature. 2017;552:159–160. doi: 10.1038/d41586-017-08236-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquieta, C. 2014. Bachelet Cede a Presión Mediática Y Anuncia Protección De Glaciares.” El Mostrador, 2014. Retrieved 3 August, 2010, from http://www.elmostrador.cl/noticias/pais/2014/05/21/bachelet-cede-a-presion-mediatica-y-anuncia-proteccion-de-glaciares/.

- Vera, A. 2017. Cinco fallecidos y 15 desaparecidos tras aluvión en Villa Santa Lucía. La Tercera. Retrieved 16 December, 2007.

- Vicuña S, Garreaud R, McPhee J. Climate change impacts on the hydrology of a snowmelt driven basin in semiarid Chile. Climatic Change. 2011;105:469. doi: 10.1007/s10584-010-9888-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent C, Auclair S, Le Meur E. Outburst flood hazard for glacier-dammed Lac de ochemelon, France. Journal of Glaciology. 2010;56(195):91–100. doi: 10.3189/002214310791190857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vuille M, Franquist E, Garreaud R, Lavado Casimiro WS, Cáceres B. Impact of the global warming hiatus on Andean temperature. Journal of Geophysical Research. 2015;120:3745–3757. doi: 10.1002/2015JD023126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R, Glasser N, Reynolds J, Harrison S, Iribarren Anacona P, Schaefer M, Shannon S. Glacial lakes of central and Patagonian Andes. Global and Planetary Change. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2018.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Younker, K. 2010. Ley De Glaciares: Caught in the balance. The Argentina independent. Retrieved 19 October, 2016, from http://www.argentinaindependent.com/socialissues/environment/ley-de-glaciares-caught-in-the-balance/.