Abstract

The white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) suffered a severe population decline due to environmental pollutants in the Baltic Sea area ca. 50 years ago but has since been recovering. The main threats for the white-tailed eagle in Finland are now often related to human activities. We examined the human impact on the white-tailed eagle by determining mortality factors of 123 carcasses collected during 2000–2014. Routine necropsy with chemical analyses for lead and mercury were done on all carcasses. We found human-related factors accounting for 60% of the causes of death. The most important of these was lead poisoning (31% of all cases) followed by human-related accidents (e.g. electric power lines and traffic) (24%). The temporal and regional patterns of occurrence of lead poisonings suggested spent lead ammunition as the source. Lead shot was found in the gizzards of some lead-poisoned birds. Scavenging behaviour exposes the white-tailed eagle to lead from spent ammunition.

Keywords: Disease, Finland, Lead poisoning, Mercury, Mortality factors, White-tailed eagle

Introduction

The white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) (WTE) is the largest raptor in the area of the Baltic Sea. The population has experienced a near extinction in the 1970s but since the late 1980s, a steady increase has been observed (Herrmann et al. 2011). However, the Finnish population is still considered vulnerable due to the small population size (958 mature individuals in 2015) (Tiainen et al. 2016). In the modern world, multiple pressures from the expanding human population can increase mortality and affect the population (Helander and Stjernberg 2002). Environmental pollutants, mainly DDE and PCBs, seriously disturbed the Baltic WTE breeding in the 1960s and 70s (Helander et al. 2002, 2008). Various traumatic deaths due to traffic or human constructions such as electric power lines and wind turbines are common in white-tailed eagles (Krone et al. 2006; Krone et al. 2009; Bevanger et al. 2010). Even intentional persecution (poisoning, shooting) of white-tailed eagles is known to happen occasionally (Krone et al. 2009; Saurola et al. 2013). The main threats of the Finnish WTEs are now considered to be human disturbance and traffic along with construction, forestry and illegal killing (Tiainen et al. 2016).

Lead poisoning from spent ammunition has long been a concern in a wide variety of bird species (Mateo 2009; Pain et al. 2009) and Haliaeetus spp. are particularly affected worldwide (e.g. Iwata et al. 2000; Helander et al. 2009; Franson and Russell 2014). Scavenging raptors like the WTE are at risk when they feed on offal and carcasses with lead bullet fragments and shots (Pain et al. 2009; Nadjafzadeh et al. 2013). The toxic effects of lead on both animals and humans have been considered so serious that many countries have adopted restrictions on the use of lead ammunition in hunting (Mateo 2009; Delahay and Spray 2015). However, the transition to non-toxic ammunition has met resistance and recently there has been opposite development as Norway lifted the ban on lead ammunition in terrestrial hunting (Arnemo et al. 2016).

Previously, the mortality factors of Finnish WTEs have been studied using a small sample of dead birds collected in 1994–2001 (Krone et al. 2006). In this study, the two main causes of death were electrocution and lead poisoning. Causes of death of ringed WTEs have also been recorded in the Ringing Centre of the Finnish Museum of Natural History but these findings are mostly based on external observations, not actual post-mortem examinations.

We studied the mortality factors of the Finnish white-tailed eagle population by examining individuals that had been euthanised or found dead in the field. The study is based on a large material collected from the whole Finnish range during the 2000s. The aim of the study is to determine more reliably than previously the variety of causes of death and the proportion of human-induced mortality compared to natural in the Finnish range of H. albicilla. We take a closer look at lead poisoning to see the extent of the problem and the possible predisposing factors. Eventually, the white-tailed eagle serves as a sentinel for environmental lead. Understanding the significance of various anthropogenic mortality factors of the population is the basis for finding the best mitigating measures.

Materials and methods

The material consisted of 123 carcasses of white-tailed eagles found dead or euthanised because of illness or injury. Carcasses were collected during 2000–2014 and either stored frozen before examination or examined freshly. Examinations were performed in 2008–2014. Only carcasses that were suitable for chemical analyses of the liver were included in the study, i.e. skeletons and severely scavenged or mummified carcasses were not included. Whole carcasses were weighed. Gender was confirmed upon necropsy by inspecting genitalia. Age was determined by plumage and/or by rings. All birds were categorised as adult type (5th autumn and older) or younger. Birds examined in 2011 and later (113 individuals, i.e. 92%) were further placed in three age classes: juvenile (1st year to 2nd spring), immature (2nd autumn to 5th spring) and adult type (5th autumn and older). Exact age (year of death minus year of birth) was known for 83 birds that were ringed as nestlings. Their age range was 0–26 years. There were more females (70) than males (50). Gender could not be confirmed in three cases. Most birds were adult type (83), 20 were immature and 20 juvenile.

A routine necropsy to determine the cause of death was performed on all carcasses. Liver and, when available, kidney were collected for analyses of lead and mercury concentration. The condition and the extent of decomposition of the carcasses varied greatly and, consequently, histology and bacteriology were performed only when deemed feasible and necessary for diagnosis. Tissue samples for histology were fixed in buffered 10% formalin solution. Fixed tissue was embedded in paraffin blocks, cut into 6 μm slices on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE) stain. Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) stain was used to detect acid-fast rod bacteria, i.e. mycobacteria in tissue. Aerobic bacteriological cultures of selected organs (usually lung, liver and intestine) were performed on blood agar and incubated in 37°C when there was a suspicion of bacterial infection. For anaerobic cultures, fastidious anaerobic agar (FAA) was used.

Lead poisoning was diagnosed when chemical analysis of liver (and kidney) revealed toxic lead concentration, and typical pathology (e.g. enlarged gall bladder filled with viscous dark green bile) was found. A liver concentration of lead > 5 mg/kg was deemed to be poisoning (Franson 1996) even when the carcass was too decomposed for complete necropsy. As for traumatic cases, background information was taken into account when determining the cause of death. For example, carcass found under an electric power line with signs of trauma was classified as power line collision.

For further analyses, the cases were divided in two main categories: human-related and other, “natural” diagnoses. The human-related diagnoses were further classified in three categories: (1) lead poisoning (2) trauma (collisions into cars, trains, wind turbines or electric power lines; getting entangled in nets or fences) and (3) shooting injuries. Natural diagnoses were divided in two categories: (1) trauma (territorial fights, drowning, unspecific trauma) and (2) disease or starvation.

Samples were additionally categorised according to region and season. Regional categories, Åland and continental Finland, were chosen because the use of lead shot is allowed in all hunting in Åland Islands, while in continental Finland lead shot has been banned in wetland hunting since 1996. Most of the material came from continental Finland (75) while 48 originated from Åland. Seasonal categories, in which the bird was assigned based on the date of finding, are three periods of equal length: autumn (September–December), winter (January–April), summer (May–August). The autumn season is the main hunting season for moose (Alces alces) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), and offal contaminated by lead ammunition residues is likely available. The winter period is characterised by snow and ice cover on lakes and sea and less chances for fishing and preying on waterfowl. The summer period is the warm season when diet range is wider than in the cold season. Seasonal distribution of samples was as follows: autumn 28, winter 53 and summer 41. One individual was not placed in any season because the exact date of finding was missing.

Chemical analyses

Lead concentration was analysed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer, ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, XSeries 2), as in Damerau et al. (2012). The limit of quantitation (LOQ) for lead is 0.010 mg/kg.

Mercury concentrations were analysed by mercury analyzer (AMA254 Advanced Mercury Analyzer, LECO and DMA-80 Direct Mercury Analyzer, Milestone) using direct combustion (in 750°C) in an oxygen-rich environment with no sample pre-treatment (sample size about 0.1 g). The LOQ was 0.020 mg/kg.

Finnish Accreditation Service (FINAS) has accredited both chemical methods and the laboratory conforms to the requirements of the standard SFS-EN ISO/IEC 17025:2005. Results are shown as mg/kg wet weight.

Statistical analyses

Generalised linear modelling (IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0) was used to assess the effects of age category (immature/adult), sex, region (Åland/continental Finland) and season (autumn, winter, summer) on the occurrence of lead poisoning (with binomial distribution and logit link function).

Because the distribution of mercury values was skewed, the values were log transformed before statistical analysis. Generalised linear modelling was used to study the effects of age class (juvenile, subadult or adult), sex and region (Åland or continental Finland) on mercury concentrations in liver and kidneys (with linear distribution). Season was not a factor because of the long-term nature of mercury accumulation. We excluded one exceptionally high kidney mercury value from the modelling as an outlier (82 mg/kg) because all other values remained under 30 mg/kg.

Selection of the best model was based on Akaike information criteria (AIC) and Akaike weights (Burnham and Anderson 2002). Akaike weights (w) were calculated among the models in which the AIC difference to the best model (Δi) was < 2.

Results

Causes of mortality

Human-related diagnoses accounted for 60% of all cases (Table 1). The most important of these was lead poisoning (31%) followed by traumatic death (24%). Collision on power lines was the most common type of trauma. There were four train and one car collision accidents. Shooting injuries were not immediately lethal in most (4/6) cases. Shots had injured legs or wings or punctured intestine leading to peritonitis.

Table 1.

Summary of the main diagnoses

| Diagnosis group | Young | Adult | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Human related | 30 (75%) | 44 (53%) | 74 (60%) |

| 1.1 Lead poisoning | 17 (43%) | 21 (25%) | 38 (31%) |

| 1.2 Trauma | 12 (30%) | 18 (22%) | 30 (24%) |

| 1.2.1 Electric power line | 7 (18%) | 12 (14%) | 19 (15%) |

| 1.2.2 Traffic | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | 5 (4.1%) |

| 1.2.3 Wind turbine | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| 1.2.4 Entangled (net/fence) | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (3.6%) | 4 (3.3%) |

| 1.3 Shooting | 1 (2.5%) | 5 (6.0%) | 6 (4.9%) |

| 2. Natural and other | 10 (25%) | 39 (47%) | 49 (40%) |

| 2.1 Trauma | 4 (10%) | 28 (34%) | 32 (26%) |

| 2.1.1 Territorial fight | 0 | 11 (13%) | 11 (8.9%) |

| 2.1.2 Drowning | 2 (5.0%) | 5 (6.0%) | 7 (5.7%) |

| 2.1.3 Other trauma | 2 (5.0%) | 12 (14%) | 14 (11%) |

| 2.2 Disease/starvation | 6 (15%) | 10 (12%) | 16 (13%) |

| 2.3 Unknown | 0 | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| N | 40 (100%) | 83 (100%) | 123 (100%) |

Natural causes of death or disability were found in 40% of the cases. Various traumas were most common in this category, particularly intraspecific territorial fights among adults. In 12% of cases, there were unspecific bruises and fractures, but some of these may have been caused by territorial fights which can result in variable injuries. For example, two individuals were euthanised because of a fractured wing. Disease and/or starvation was found in 12% of the cases. Three generalised infectious diseases were diagnosed: mycobacteriosis (Mycobacterium sp., 2 cases), aspergillosis (Aspergillus fumigatus, 2 cases) and erysipelas (Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, 1 case). The erysipelas case was a secondary finding, as the main diagnosis of this individual was lead poisoning. Local bacterial infections of the joint were found in two cases, caused by E. rhusiopathiae and Staphylococcus aureus. Cholecystitis and/or cholangiohepatitis (gall bladder and/or bile duct inflammation) along with starvation was the main diagnosis in four cases. Two of these were examined bacteriologically and Clostridium perfringens was isolated from the gall bladder. Starvation as main diagnosis was diagnosed in four cases. Three individuals had arthritis in one joint and one was euthanised because of deformed quills of the wings. In one case, the cause of death was not established but lead poisoning could be ruled out.

In adults, the most important cause of death was natural or unspecific trauma with lead poisoning as second (Table 1). In the younger age category, the most important factor was lead poisoning but disease/starvation was also significant.

There were significant differences between the mean weights of the birds in different diagnostic groups, similar in both sexes (ANOVA, F = 22.556, P < 0.001). The lowest mean weights were found in the disease group and the lead-poisoning group (Table 2). Both trauma groups, human-related and natural, had the highest mean weights (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean weights in kilograms (with standard error) of white-tailed eagle carcasses and lead concentration (mg/kg wet weight) in liver in each diagnostic group

| Diagnosis | Male kg ± SE (n) | Female kg ± SE (n) | Pb median | Pb mean | Pb max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead poisoning | 3.18 ± 0.15 (17) | 3.98 ± 0.15 (17) | 21.0 | 18.7 (SD 7.7) | 35.0 |

| Trauma, human related | 4.20 ± 0.16 (12) | 5.68 ± 0.23 (15) | 0.12 | 0.18 (SD 0.16) | 0.59 |

| Shooting injury | 3.36 ± 0.37 (4) | 4.68 ± 1.53 (2) | 0.32 | 0.32 (SD 0.22) | 0.63 |

| Trauma, natural | 4.59 ± 0.22 (9) | 5.18 ± 0.18 (19) | 0.08 | 0.16 (SD 0.22) | 1.1 |

| Disease | 3.06 ± 0.34 (4) | 3.75 ± 0.19 (11) | 0.35 | 0.51 (SD 0.51) | 1.8 |

Lead

Lead poisoning was diagnosed in 38 birds in which the mean liver lead concentration was 18.7 mg/kg (SD 7.7 mg/kg), median 21.0 mg/kg and range 3.5–35.0 mg/kg. Lead concentration in kidneys was determined in 36 of the poisoning cases with a mean value 9.2 mg/kg (SD 3.0 mg/kg), median 8.8 mg/kg and range 4.5–15.0 mg/kg. Two cases had liver values < 5 mg/kg (3.5 and 4.0), but they had higher kidney concentrations (9.6 and 5.9, respectively), and pathology consistent with lead poisoning. The case with the lowest liver concentration was euthanised due to inability to fly. Lead shot (1–5 per bird) were found in the gizzard of five eagles (13.5%). All five originated from Åland.

Pathologically, lead poisonings could be roughly categorised in two forms: more chronic form with severe muscle wasting (55%), and more acute form with some fat reserves remaining and moderate muscular condition (45%). However, even individuals with abundant fat reserves had always detectable muscle wasting. The most consistent finding was abnormally thick or dry and dark green bile in an engorged gall bladder (97%). In 74% of cases, the gizzard was empty or contained only lead shot.

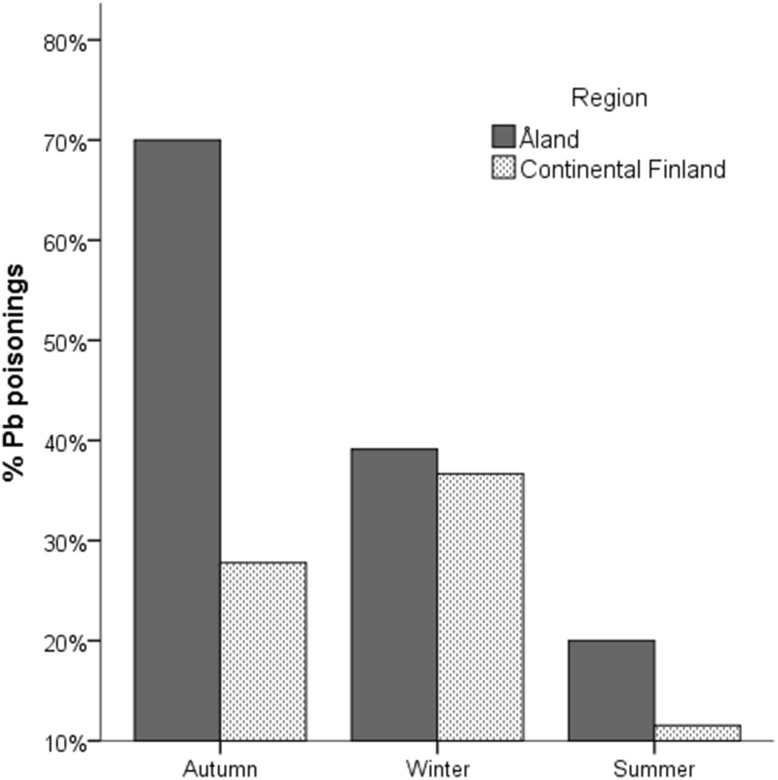

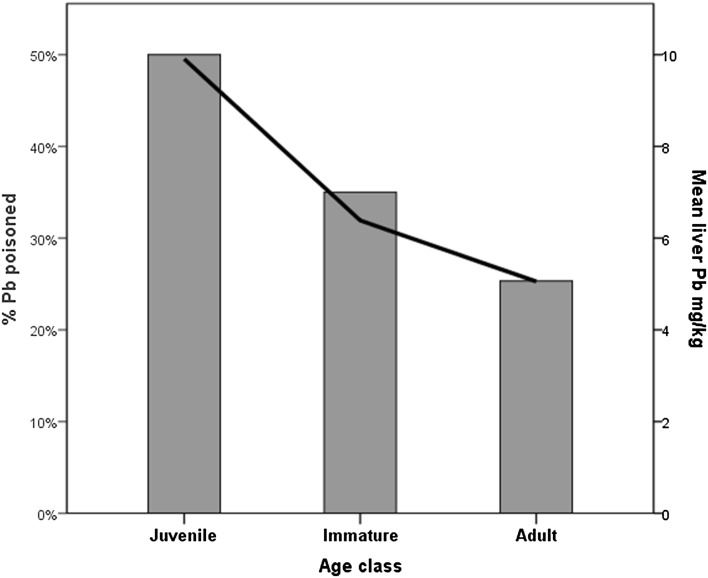

The best model describing the occurrence of lead poisoning included region and season (Table 3). Cases were more common in Åland than in the continent (Fig. 1). Lead poisoning was most common in the two cold seasons (Fig. 1). The second best model, with almost equal weight as the best, included additionally age category. Lead poisoning was most common in juveniles (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

The best models (ΔAICc < 2) describing (A) the occurrence of lead poisoning in white-tailed eagles (B) the mercury levels (mg/kg wet weight, log transformed) in liver and (C) the mercury levels (mg/kg wet weight, log transformed) in kidney according to generalised linear modelling with Akaike weights (w), number of variables (K), Akaike information criteria value corrected for small sample size (AICc) and the difference of the model’s AICc to that of the best model (ΔAICc). Variables are SEASON = time of sampling (January–April, May–August or September–December), REGION = sampling region (Åland/Continental Finland), AGE = age class (immature/adult) and sex (male/female)

| Dependent | Rank | Model | K | AICc | ΔAIC | w |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Lead poisoning (yes/no) | 1 | SEASON + REGION | 4 | 65.74 | 0 | 0.28 |

| 2 | SEASON + REGION + AGE | 5 | 65.96 | 0.22 | 0.25 | |

| 3 | SEASON + REGION + SEX | 5 | 67.35 | 1.60 | 0.12 | |

| 4 | SEASON + AGE | 4 | 67.38 | 1.64 | 0.12 | |

| 5 | SEASON | 3 | 67.47 | 1.73 | 0.12 | |

| 6 | SEASON + REGION + AGE + SEX | 6 | 67.56 | 1.81 | 0.11 | |

| (B) Mercury liver (log mg/kg) | 1 | AGE | 2 | 192.86 | 0 | 0.34 |

| 2 | AGE + REGION | 3 | 193.21 | 0.35 | 0.29 | |

| 3 | AGE + SEX | 3 | 193.87 | 1.01 | 0.21 | |

| 4 | AGE + SEX + REGION | 4 | 194.25 | 1.38 | 0.17 | |

| (C) Mercury kidney (log mg/kg) | 1 | AGE + REGION | 3 | 202.25 | 0 | 0.71 |

| 2 | AGE + REGION + SEX | 4 | 204.03 | 1.79 | 0.29 |

Fig. 1.

Regional and seasonal differences in the occurrence of lead poisonings in white-tailed eagles

Fig. 2.

Differences in liver lead concentrations (mg/kg wet weight; black line) between age classes and the proportion of lead-poisoned WTE’s in each age class (grey bars)

Mean and median lead concentrations in the liver in the individuals that had not been lead poisoned were 0.24 (SD 0.31) mg/kg and 0.14 mg/kg, respectively, and in kidney 0.39 (SD 0.53) mg/kg and 0.17 mg/kg, respectively. When comparing lead concentrations between different diagnostic groups other than lead poisoning, there were significant differences in liver values (df = 3, Χ2 = 13.701, P = 0.003; Table 2). The highest mean and median liver values were found in the disease group, and the lowest values in the natural trauma group. There were no significant differences between groups in kidney lead levels (df = 3, Χ2 = 6.871, P = 0.076).

Four individuals had liver lead levels in the range 1.0–1.8 mg/kg. These were the next highest levels below actual poisoning cases. Three of these were diagnosed in the disease group. One had aspergillosis, one had mycobacteriosis and one was diagnosed with arthritis of the hock joint and staphylococcal infection. The fourth case had drowned in a fishing net.

Because of varying and often small annual sample sizes, we calculated three-year averages of the annual proportion of lead-poisoned birds. The proportion varied around 30% during the whole period (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of lead-poisoned white-tailed eagles, three-year moving averages. Number of examined birds is shown above the value points

Mercury

The best model for liver mercury concentration included only age class (Table 3). For kidney mercury concentration, the best model included age class and region. Mercury levels in both liver and kidney increased with age (Table 4, Fig. 4). Kidney mercury level was higher in Åland than in the continent.

Table 4.

Mercury concentration (mg/kg wet weight) in liver and kidney of white-tailed eagles. Values for each age class (juvenile/immature/adult) are presented separately

| Age class | Organ | N | Median | Mean | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juvenile | Liver | 19 | 1.1 | 2.16 (SD 2.10) | 7.8 |

| Kidney | 19 | 2.1 | 3.43 (SD 4.06) | 17.2 | |

| Immature | Liver | 20 | 2.0 | 2.39 (SD 1.78) | 6.2 |

| Kidney | 20 | 4.4 | 5.46 (SD 5.37) | 19.0 | |

| Adult | Liver | 81 | 3.0 | 4.75 (SD 4.14) | 17.2 |

| Kidney | 73 | 8.2 | 9.60 (SD 6.92) | 82.0 | |

| All | Liver | 120 | 2.6 | 3.94 (SD 3.75) | 17.2 |

| Kidney | 113 | 5.9 | 8.47 (SD 9.67) | 82.0 |

Fig. 4.

Mean mercury concentrations (log transformed) in liver and kidney in three main age classes [N (liver) = 120, N (kidney) = 113]

When looking at mercury levels on a more detailed age level, the values did not seem to increase in age groups older than 8–10 years and the variation was greater in the oldest age groups (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mean mercury concentrations (log transformed) in liver and kidney in eight age categories [N (liver) = 83, N (kidney) = 77]

The differences in mercury levels between diagnostic groups were not significant for liver (df = 4, Χ2 = 9.069, P = 0.059) nor for kidney (df = 4, Χ2 = 8.085, P = 0.089).

One adult male (10 years old) had an exceptionally high mercury concentration in the kidney (82 mg/kg). However, the immediate cause of death was trauma (fractured sternum). Body condition was normal and the bird had been able to feed on a hare shortly before death, i.e. poisoning was not suspected. Additionally, high kidney mercury levels in the range 20–30 mg/kg were found in 7 individuals (6.2% of all).

Discussion

Anthropogenic factors accounted for more than half of the white-tailed eagle mortality in our sample. The impact was even stronger in juvenile birds in which 75% of cases had died of human-related causes. The most important of these factors was lead poisoning (31% of all cases). The proportion was greater than in an earlier study of 11 Finnish WTEs where lead levels indicating poisoning were found in two cases (18%) (Krone et al. 2006). Such a high frequency of lead poisonings poses a possible threat to the population but the relatively harder impact on immature birds may reduce the effect. In Swedish WTEs, which share the Baltic Sea habitat with their Finnish conspecifics, elevated lead concentrations were found in 22%, and levels indicating lead poisoning in 14% of the birds (Helander et al. 2009). During the data collection period 2000–2014, there was no evident change in the annual frequency of lead poisoning: the proportion varied around 30%. Lead toxicosis is a well-known problem in Haliaeetus spp. and it has been recorded worldwide: in Sweden (Helander et al. 2009), in Germany and Austria (Kenntner et al. 2001; Müller et al. 2007), in USA (Stauber et al. 2010; Franson and Russell 2014), in Canada (Wayland and Bollinger 1999), in Greenland (Krone et al. 2004) and in Japan (Iwata et al. 2000).

Our findings support directly and indirectly the notion that spent lead ammunition is the cause of the poisonings. We found lead shot in the gizzards of some (13.5%) of the poisoned birds but never in gizzards of birds with other diagnoses. Lead was a problem particularly in Åland. The availability of lead ammunition in the environment in Åland is greater since lead shot is legal in all hunting there, whereas in continental Finland lead shot has been banned in wetland hunting since 1996. However, lead poisoning was frequently found in continental Finland indicating a source from terrestrial hunting or non-compliance with lead shot ban. Temporally, the highest frequency of lead poisonings (43%) was observed during autumn season (September–December) which coincides with the main hunting season. The seasonality of lead poisonings in Haliaeetus spp., connected to hunting and cold season, has been observed also in earlier studies (e.g. Stauber et al. 2010; Müller et al. 2007). In autumn, decreasing fish availability and increasing availability of hunting offal can cause a diet switch and expose the bird to lead fragments from bullets (Krone et al. 2006; Nadjafzadeh et al. 2013). Lead bullets can be fragmented into hundreds of large and small pieces widely along the wound channel in deer tissues and offal (Hunt et al. 2006). In the summer season (May–August), lead poisonings were notably less common although not absent. The breeding season diet of Finnish WTE’s in the Baltic Sea region consists mainly of birds and fish with only very small proportion of mammals (Sulkava et al. 1997; Ekblad et al. 2016). However, feeding on birds may also be risky because of lead shot embedded in the tissues of game birds: a German study found over 20% of live X-rayed geese having shot in their tissues (Krone et al. 2008).

Pathology of lead poisoning in the white-tailed eagle resembled that of the bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) (Franson and Russell 2014): enlarged gall bladder and poor condition were typical common features. Green staining of gizzard and intestinal contents is also common. Mean weights of lead-poisoned WTEs were 3.18 and 3.98 kg in males and females, respectively, while the corresponding weights of normal living WTEs were estimated to be 4.7 kg for males and 5.9 kg for females (Koivusaari et al. 2003). Even considering post-mortem desiccation of the carcass, severe weight loss was associated with lead poisoning.

When comparing liver lead levels in diagnostic groups other than lead-poisoning group, the disease group had the highest mean value. This would suggest that even sublethal lead concentrations can have notable negative effects on the health of the bird. Experimentally, lead exposure in birds has been linked to depressed enzyme function of red blood cells and anaemia (Hoffman et al. 1981; Redig et al. 1991). Even low levels of lead in human organ system can be harmful and the same is likely to apply also to birds (Hunt 2012; EFSA 2013). Subclinical levels of lead in blood were negatively connected with body condition in wild whooper swans (Cygnus cygnus) in Britain (Newth et al. 2016). In eiders (Somateria mollissima), a negative correlation between blood lead concentration on subclinical level and condition on arrival at the breeding grounds has been found (Provencher et al. 2016). In golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), subclinical concentration of lead in blood was negatively related to flight height and movement rate (Ecke et al. 2017). We did not find evidence that subclinical lead levels in liver would be connected with increased risk of trauma. The same result was found in the bald eagle and the golden eagle in the USA (Franson and Russell 2014).

The tissue concentrations of mercury increased with age suggesting tolerance of slowly accumulating mercury. Fish in the Baltic Sea are a steady source of mercury for piscivorous birds (HELCOM 2010). When looking closer at age differences it seemed that mercury concentrations in kidneys did not steadily rise with age but started to level off and have more variation after 8–10 years of age (Fig. 5). One explanation for this might be that mortality is increased in the oldest individuals in which mercury levels have reached a sufficiently high level. However, the small sample size of oldest individuals may confound the results. In the 1960s when the Finnish WTE population was seriously declining, Henriksson et al. (1966) found some extremely high mercury concentrations (the highest 123 mg/kg in kidney) in eagles found dead and, accordingly, diagnosed mercury poisoning in five out of six individuals. In eleven Finnish WTEs collected in 1994–2001, the mercury levels were close to the level of this study (Krone et al. 2006). In contrast, mercury values of WTEs from Germany and Austria (Kenntner et al. 2001) and Poland (Kalisinska et al. 2014) were lower, median concentrations for both liver and kidney being < 1 mg/kg.

In our material there was an individual with potentially toxic kidney mercury level but the significance of this finding remained uncertain, as the immediate cause of death was trauma. Kidney levels are generally higher than liver levels (Kenntner et al. 2001; Kalisinska et al. 2014). Mercury concentrations in tissues of birds found dead can be difficult to interpret. Marine mammals and birds can potentially have very high mercury levels in tissues without serious consequences (Heinz 1996). Most likely, the reason for this tolerance is having the mercury in a less toxic form instead of the most toxic form, methylmercury. In the WTE, the proportion of methylmercury in kidney is found to be lower than in liver, muscle or brain (Kalisinska et al. 2014). Interaction between selenium and mercury can also lower the toxicity of either metal in adult birds (Heinz and Hoffman 1998).

Traumas related to human activity were important mortality factors for white-tailed eagles in our material. The most dangerous human constructions were electric power lines which were the cause of death in 15% of the cases. This is a much lower proportion than that found in the data from ringed WTEs in which 55% of cases were classified as power line collisions and electrocutions (Saurola et al. 2013) and also lower than the 36% found by Krone et al. (2006). The problem has been recognised by experts and the energy industry, and protective measures to “disarm” the most dangerous electric poles have been taken. A manual on protection of large birds from electrocutions was issued in 2009 by WWF Finland and energy companies (e.g. Stjernberg et al. 2009). It seems that the protective measures may indeed have decreased power line accidents.

With the active construction of wind turbines along coastal regions overlapping white-tailed eagle habitat, the risk of these large birds hitting turbines should be increasing. However, collisions with wind turbines were rare, only two cases were found. Traffic accidents and, also, getting trapped in nets or fences were more common findings than wind turbine collisions. However, not all wind turbine collisions are submitted to pathological examination and WTE experts have knowledge of at least 10 such collisions in Finland in 2000s (T. Stjernberg, pers. comm.). WTE mortality and decreased breeding success due to wind turbines in important WTE habitat has been recorded in Norway (Dahl et al. 2012). Increasing knowledge about risks associated with wind farms encouraged the Finnish WTE working group and WWF Finland to compile guidelines for eagle-safe wind farm construction (Nuuja 2017). Telemetry study of dispersing juveniles showed that risks can be reduced by avoiding construction of wind turbines along the coastline and with a 2 km buffer zone between WTE nests and turbines (Balotari-Chiebao et al. 2016).

Intentional persecution of the white-tailed eagle has apparently decreased since the earlier part of the 20th century (Saurola et al. 2013) but we still found evidence of shooting injuries in six individuals. Shots were not always immediately lethal but instead damaged wings, legs or internal organs leading to incapacity to fly or inflammatory disease. In a study of German WTEs, a similar situation was found as the shot birds had died of lingering illness caused by the shooting (Krone et al. 2009). Of course, some shooting cases may be missing from pathological studies because they are not submitted to examination, for legal or illegal reasons.

Infectious diseases were rare findings in our material. Generalised infections were caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium sp. (mycobacteriosis) and Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae (erysipelas) and the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus (aspergillosis) and five individuals in total had been infected. Mycobacteriosis, also referred to as avian tuberculosis, has earlier been found in bald eagles (e.g. Heatley et al. 2007) but for WTEs, reports are lacking. E. rhusiopathiae is a well-known porcine infectious agent with zoonotic potential. However, it can survive in marine and freshwater environment where fish can be carriers and cause disease in fish-eating birds (Brooke and Riley 1999). Aspergillosis is typically a respiratory disease especially in immunocompromised birds (Thomas et al. 2007). None of these agents are known for causing wider mortality in raptor populations, but rather isolated incidents. However, in juvenile WTE’s diseases and starvation were relatively important, being the third most important diagnostic category in our material. A rare epidemic of infectious disease in Baltic Sea WTEs was seen recently in 2016–2017 when highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI) H5N8 was found to infect WTEs (OIE 2017). Warming winters in the north with more overwintering waterfowl that carry viruses may increasingly expose WTEs to HPAI.

Conclusion

Our study showed that various human-related factors dominated the causes of death in Finnish white-tailed eagles. The most troubling finding was the large amount of lead poisonings throughout the study period. Although lead shot has been banned in waterfowl hunting in continental Finland for two decades, they are legal in terrestrial hunting exposing the eagles to lead embedded in mammal carcasses and offal. Åland allows lead ammunition in all hunting, including spring hunt of eiders, important prey of the WTE. General wildlife health surveillance in Finland reveals annually lead poisonings particularly in WTEs and whooper swans (Finnish Food Safety Authority database). Decisive protective actions have been taken to help the WTE to avoid environmental contaminants, electrocutions and wind turbine collisions. Further measures are needed to control the toxic effects of lead from ammunition for the protection of both animal and human health. Replacing harmful lead ammunition with non-toxic alternatives is a feasible solution.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our thanks to the people who submitted or reported dead or diseased white-tailed eagles suitable for this study. We warmly thank the competent staff of the Finnish Food Safety Authority, especially Minna Nylund, Perttu Koski, Nina Aalto and Annette Brockmann for their help in post-mortem examinations.

Biographies

Marja Isomursu

is a DVM, Ph.D. (ecology) and a senior researcher at the Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira, Veterinary Bacteriology and Pathology Research Unit, Wild and Aquatic Animal Pathology Section. Her expertise includes wildlife disease surveillance and diagnostics, with special interest in avian diseases.

Juhani Koivusaari

is a Phil. Lic. of the University of Kuopio (now University of Eastern Finland). His research interests include population ecology, food biology and environmental toxicology. He is a founding member of the WWF white-tailed eagle working group which played a crucial role in the conservation of the Finnish white-tailed eagle, with over 50 years of experience in the conservation, monitoring and research of the white-tailed eagle. He is currently retired.

Torsten Stjernberg

is an adjunct professor of the University of Helsinki. His research includes i.a. the Finnish bat fauna, otters and early ornithology and early zoological illustrators and artists. He is a founding member of the WWF Finland white-tailed eagle working group (founded 1972) with over 50 years of experience in the conservation, monitoring and research of the white-tailed eagle. He is currently an emeritus researcher at the Finnish Museum of Natural History.

Varpu Hirvelä-Koski

is a DVM, Ph.D. and a senior researcher at the Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira, Veterinary Bacteriology and Pathology Research Unit, Wild and Aquatic Animal Pathology Section. Her specialty in research is bacteriology, terrestrial and aquatic pathogens of wild and domestic animals.

Eija-Riitta Venäläinen

is a Ph.D., a senior researcher and the chief of the Inorganic Chemistry Section at the Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira. Her specialty in research are heavy metals in food and in animal tissues, especially wild animals.

Contributor Information

Marja Isomursu, Email: marja.isomursu@evira.fi.

Juhani Koivusaari, Email: juhani.koivusaari@netikka.fi.

Torsten Stjernberg, Email: torsten.stjernberg@helsinki.fi.

Varpu Hirvelä-Koski, Email: varpu.hirvela-koski@evira.fi.

Eija-Riitta Venäläinen, Email: eija-riitta.venalainen@evira.fi.

References

- Arnemo J, Andersen O, Stokke S, Thomas VG, Krone O, Pain DJ, Mateo R. Health and environmental risks from lead-based ammunition: Science versus socio-politics. EcoHealth. 2016;13:618–622. doi: 10.1007/s10393-016-1177-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balotari-Chiebao F, Villers A, Ijäs A, Ovaskainen O, Repka S, Laaksonen T. Post-fledging movements of white-tailed eagles: Conservation implications for wind-energy development. Ambio. 2016;45:831–840. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0783-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevanger, K., F. Berntsen, S. Clausen, E.L. Dahl, Ø. Flagstad, A. Follestad, D. Halley, F. Hanssen, et al. 2010. Pre- and post-construction studies of conflicts between birds and wind turbines in coastal Norway (Bird-Wind). Report on findings 2007–2010. NINA Report 620, Trondheim, Norway.

- Brooke CJ, Riley TV. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: bacteriology, epidemiology and clinical manifestations of an occupational pathogen. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1999;48:789–799. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-9-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information- theoretic approach. 2. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl EL, Bevanger K, Nygård G, Røskaft E, Stokke BG. Reduced breeding success in white-tailed eagles at Smøla windfarm, western Norway, is caused by mortality and displacement. Biological Conservation. 2012;145:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damerau A, Venäläinen ER, Peltonen K. Heavy metals in meat of Finnish city rabbits. Food Additives & Contaminants. 2012;5:246–250. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2012.702131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahay, R.J., and C.J. Spray (eds.). 2015. Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead Ammunition: understanding and minimising the risks to human and environmental health. Oxford: Edward Grey Institute, The University of Oxford.

- Ecke F, Singh NJ, Arnemo JM, Bignert A, Helander B, Berglund ÅMM, Borg H, Bröjer C, et al. Sublethal lead exposure alters movement behavior in free-ranging golden eagles. Environmental Science and Technology. 2017;51:5729–5736. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b06024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). 2013. Scientific opinion on lead in food. Retrieved 11 April, 2017, from http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1570.

- Ekblad CMS, Sulkava S, Stjernberg TG, Laaksonen TK. Landscape-scale gradients and temporal changes in the prey species of the white-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) Annales Zoologici Fennici. 2016;53:228–240. doi: 10.5735/086.053.0401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franson C. Interpretation of tissue lead residues in birds other than waterfowl. In: Beyer WN, Heinz GH, Redmon-Norwood AW, editors. Environmental contaminants in wildlife—interpreting tissue concentrations. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1996. pp. 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Franson JC, Russell RE. Lead and eagles: demographic and pathological characteristics of poisoning, and exposure levels associated with other causes of mortality. Ecotoxicology. 2014;23:1722–1731. doi: 10.1007/s10646-014-1337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatley JJ, Mitchell MM, Roy A, Cho DY, Williams DL, Tully TN. Disseminated Mycobacteriosis in a Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery. 2007;21:201–209. doi: 10.1647/1082-6742(2007)21[201:DMIABE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz GH. Mercury poisoning in wildlife. In: Fairbrother A, Hoff GL, Locke LN, editors. Noninfectious diseases of wildlife. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press; 1996. pp. 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz GH, Hoffman DJ. Methylmercury chloride and selenomethionine interactions on health and reproduction in mallards. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 1998;17:139–145. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620170202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helander B, Stjernberg T. Action Plan for the conservation of White-tailed Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) Strasbourg: Birdlife International; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Helander B, Olsson A, Bignert A, Asplund L, Litzén K. The role of DDE, PCB, coplanar PCB and eggshell parameters for reproduction in the white-tailed sea eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) in Sweden. Ambio. 2002;31:386–403. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-31.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander B, Bignert A, Asplund L. Using raptors as environmental sentinels: Monitoring the white-tailed sea eagle Haliaeetus albicilla in Sweden. Ambio. 2008;37:425–431. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[425:URAESM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander B, Axelsson J, Borg H, Holm K, Bignert A. Ingestion of lead from ammunition and lead concentrations in white-tailed sea eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) in Sweden. Science of the Total Environment. 2009;407:5555–5563. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELCOM (Helsinki Commision). 2010. Hazardous substances in the Baltic Sea – An integrated thematic assessment of hazardous substances in the Baltic Sea. Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings No. 120B. Retrieved February, 2018, from http://www.helcom.fi/Lists/Publications/BSEP120B.pdf.

- Henriksson K, Karppanen E, Helminen M. High residues of mercury in Finnish white-tailed eagles. Ornis Fennica. 1966;43:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, C., O. Krone, T. Stjernberg, and B. Helander. 2011. Population development of baltic bird species: White-tailed sea eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla). HELCOM Baltic Sea Environment Fact Sheets. Retrieved May, 2017, from http://www.helcom.fi/baltic-sea-trends/environment-fact-sheets/.

- Hoffman DJ, Pattee OH, Wiemeyer SN, Mulhern B. Effects of lead shot ingestion on δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase activity, hemoglobin concentration and serum chemistry in bald eagles. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 1981;17:423–431. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-17.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt WG. Implications of sublethal lead exposure in avian scavengers. Journal of Raptor Research. 2012;46:389–393. doi: 10.3356/JRR-11-85.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt WG, Burnham W, Parish CN, Burnham KK, Mutch B, Oaks JL. Bullet fragments in deer remains: Implications for lead exposure in avian scavengers. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 2006;34:167–170. doi: 10.2193/0091-7648(2006)34[167:BFIDRI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata H, Watanabe M, Kim E-Y, Gotori R, Yasunaga G, Tanabe S, Masuda Y, Fujita S. Contamination by chlorinated hydrocarbons and lead in Steller’s Sea-Eagle and White-tailed Eagle from Hokkaido, Japan. In: Ueta M, McGrady MJ, editors. First symposium on Steller’s and white-tailed eagles in East Asia. Tokyo: Wild Bird Society of Japan; 2000. pp. 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kalisinska E, Gorecki J, Lanocha N, Okonska A, Melgarejo JB, Budis H, Rzad I, Golas J. Total and methylmercury in soft tissues of white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) and Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) collected in Poland. Ambio. 2014;43:858–870. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0533-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenntner N, Tataruch F, Krone O. Heavy metals in soft tissue of white-tailed eagles found dead or moribund in Germany and Austria from 1993 to 2000. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2001;20:1831–1837. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620200829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivusaari, J., T. Stjernberg, H. Ekblom, and J. Högmander. 2003. Daily body weight, amount of food and time of feeding of white-tailed sea eagles at Finnish winter feeding stations 1992–2000. In: SEA EAGLE 2000. Proceedings from an international conference at Björkö, Sweden, 13–17 September 2000, ed. B. Helander, M. Marquiss, and W. Bowerman. Stockholm: Swedish Society for Nature Conservation/SNF & Åtta.45 Tryckeri AB.

- Krone O, Wille F, Kenntner N, Boertmann D, Tataruch F. Mortality factors, environmental contaminants, and parasites of white-tailed sea eagles from Greenland. Avian Diseases. 2004;48:417–424. doi: 10.1637/7095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone O, Stjernberg T, Kenntner N, Tataruch F, Koivusaari J, Nuuja I. Mortality factors, helminth burden, and contaminant residues in white-tailed sea eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) from Finland. Ambio. 2006;35:98–104. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2006)35[98:MFHBAC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone O, Kenntner N, Trinogga A, Nadjafzadeh M, Scholz F, Sulawa J, Totschek K, Schuck-Wersig P, et al. Lead poisoning in white-tailed sea eagles: causes and approaches to solutions in Germany. In: Watson RT, Fuller M, Pokras M, Hunt WG, et al., editors. Ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: Implications for wildlife and humans. Boise, ID: The Peregrine Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krone O, Kenntner N, Tataruch F. Gefährdungsursachen des Seeadlers. Denisia. 2009;27:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo R. Lead poisoning in wild birds in Europe and the regulations adopted in different countries. In: Watson RT, Fuller M, Pokras M, Hunt WG, editors. Ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: Implications for wildlife and humans. Boise, ID: The Peregrine Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Müller K, Altenkamp R, Brunnberg L. Morbidity of free-ranging white-tailed sea eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) in Germany. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery. 2007;21:265–274. doi: 10.1647/2007-001R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadjafzadeh M, Hofer H, Krone O. The link between feeding ecology and lead poisoning in white-tailed eagles. Journal of Wildlife Management. 2013;77:48–57. doi: 10.1002/jwmg.440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newth JL, Rees EC, Cromie RL, McDonald RA, Bearhop S, Pain DJ, Norton GJ, Deacon C, et al. Widespread exposure to lead affects the body condition of free-living whooper swans Cygnus cygnus wintering in Britain. Environmental Pollution. 2016;209:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuuja, I. (ed.). 2017. Merikotkien puolesta—WWF:n merikotkatyöryhmän vuosikymmenten taival. Helsinki: WWF Finland report. (For the white-tailed eagles—the journey of the WWF white-tailed eagle working group. In Finnish).

- OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health). 2017. Update on highly pathogenic avian influenza in animals (types H5 and H7). Retrieved December, 2017, from: http://www.oie.int/animal-health-in-the-world/update-on-avian-influenza/.

- Pain DJ, Fisher IJ, Thomas VG. A global update of lead poisoning in terrestrial birds from ammunition sources. In: Watson RT, Fuller M, Pokras M, Hunt WG, editors. Ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: Implications for wildlife and humans. Boise, ID: The Peregrine Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Provencher JF, Forbes MR, Hennin HL, Love OP, Braune BM, Mallory ML, Gilchrist HG. Implications of mercury and lead concentrations on breeding physiology and phenology in an Arctic bird. Environmental Pollution. 2016;218:1014–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redig PT, Lawler EM, Schwartz S, Dunnette JL, Stephenson B, Duke GE. Effects of chronic exposure to sublethal concentrations of lead acetate on heme synthesis and immune function in red-tailed hawks. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 1991;21:72–77. doi: 10.1007/BF01055559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurola P, Valkama J, Velmala W. The finnish bird ringing Atlas. Helsinki: Finnish Museum of Natural History and Ministry of Environment; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stauber E, Finch N, Talcott PA, Gay JM. Lead poisoning of bald (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and golden (Aquila chrysaetos) eagles in the US Inland Pacific Northwest Region—an 18-year retrospective study: 1991–2008. Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery. 2010;24:279–287. doi: 10.1647/2009-006.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stjernberg, T., J. Koivusaari, J. Högmander, T. Ollila, S. Keränen, G. Munsterhjelm, and H. Ekblom. 2009. Population size and nesting success of the White-tailed Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) in Finland, 2007–2008. Linnut-vuosikirja 2008: 14–21. (in Finnish, English summary).

- Sulkava S, Tornberg R, Koivusaari J. Diet of the white-tailed eagle Haliaeetus albicilla in Finland. Ornis Fennica. 1997;74:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NJ, Hunter DB, Atkinson CT. Infectious diseases of wild birds. 9. Ames, ID: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen J, Mikkola-Roos M, Below A, Jukarainen A, Lehikoinen A, Lehtiniemi T, Pessa J, Rajasärkkä A, et al. Suomen lintujen uhanalaisuus 2015—the 2015 red list of Finnish bird species. Helsinki: Ympäristöministeriö & Suomen ympäristökeskus; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wayland M, Bollinger T. Lead exposure and poisoning in bald eagles and golden eagles in the Canadian prairie provinces. Environmental Pollution. 1999;104:341–350. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00201-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]