Abstract

Eosinophilia (EOS) is an important component of airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in allergic reactions including those leading to asthma. Although cigarette smoking (CS) is a significant contributor to long-term adverse outcomes in these lung disorders, there are also the curious reports of its ability to produce acute suppression of inflammatory responses including EOS through poorly understood mechanisms. One possibility is that proinflammatory processes are suppressed by nicotine in CS acting through nicotinic receptor α7 (α7). Here we addressed the role of α7 in modulating EOS with two mouse models of an allergic response: house dust mites (HDM; Dermatophagoides sp.) and ovalbumin (OVA). The influence of α7 on EOS was experimentally resolved in wild-type mice or in mice in which a point mutation of the α7 receptor (α7E260A:G) selectively restricts normal signaling of cellular responses. RNA analysis of alveolar macrophages and the distal lung epithelium indicates that normal α7 function robustly impacts gene expression in the epithelium to HDM and OVA but to different degrees. Notable was allergen-specific α7 modulation of Ccl11 and Ccl24 (eotaxins) expression, which was enhanced in HDM but suppressed in OVA EOS. CS suppressed EOS induced by both OVA and HDM, as well as the inflammatory genes involved, regardless of α7 genotype. These results suggest that EOS in response to HDM or OVA is through signaling pathways that are modulated in a cell-specific manner by α7 and are distinct from CS suppression.

Keywords: chemokine, cigarette smoke, eosinophils, eotaxin, house dust mites, nicotine, nicotinic receptor α7, ovalbumin

INTRODUCTION

The accumulation of pulmonary eosinophils (eosinophilia, EOS) is a significant component of the airway inflammatory response following exposure to allergens (5, 21, 29, 30). Mouse models have provided a wealth of information regarding how allergens of different types initiate airway inflammatory processes, including those that lead to EOS (12, 14, 31). Two commonly investigated mouse models of allergenic response are sensitization and intranasal challenge to either ovalbumin (OVA), a protein of relatively simple antigenicity (6), or house dust mites (HDM; Dermatophagoides sp.), a complex antigen that is also a common source of contact and airborne allergens (13). After antigen sensitization and challenge, they both elicit airway inflammation, tissue remodeling, and additional allergen-associated cell-specific responses that lead to EOS. One significant difference in their mechanism of action is that OVA induces a strong Th2 immune process whereas HDM includes both Th2 and less well-defined innate processes (6, 13, 29). Thus both models offer different but complementary approaches to gain insights into the mechanisms that lead to allergen-specific EOS.

Cigarette smoking (CS) is another significant contributor to lung disorders. Curiously, although promoting adverse outcomes to pulmonary disease progression, CS has also been associated in both humans and animal models with suppression of macrophage inflammatory responses, reduced EOS, and mast cell activation in response to allergens inducing asthmalike disease (3, 25, 34). Several possibilities to explain how CS does this include a reduced response to allergens through the toxic effects of CS components and the generally adverse impact of local hypoxia. Another possibility is that the local inflammatory response is dampened when nicotine interacts with nicotinic receptors. Distinguishing among these possibilities, and the application this has to understanding links to disease or novel therapeutic approaches, has remained elusive.

This study examined the impact of CS on the EOS response by the distal lung to different allergens. Nicotine acts to modulate the lung inflammatory response mostly through its actions on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 (α7). The role of α7 signaling can be distinguished with the use of previously described mouse models termed α7G (genetically modified to coexpress green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a bicistronic marker of normal α7 receptor expression) or α7E260A:G, in which a point mutation precisely restricts calcium-mediated cell signaling (7–10, 26, 27). Studies using these mice have already demonstrated that alveolar macrophages (AMs), club cells, and alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells of the lung constitutively express α7. Furthermore, inflammatory responses to inflammagens (such as LPS) are modified in mice with the α7 point mutation through cell-specific signaling pathways of immune and epithelial cells. Here we report that normal endogenous α7 function in the mouse lung modifies the EOS response to both HDM and OVA, but through allergen-specific ways. This was determined through comparison of responses in the α7G control mouse and the α7E260A:G mouse having defective α7 receptor function. The EOS response to HDM in the α7E260A:G mouse was suppressed, whereas OVA-induced EOS in this mouse strain was substantially enhanced. RNA analysis of both AMs and enriched distal lung epithelial cells revealed expression profiles indicative of specific impacts by α7E260A:G on normal responses. In particular, the stimulation of EOS signaling chemokines (eotaxins 1 and 2) and an interacting network of pro-EOS and cell-specific genes were modulated by α7 in an allergen-specific manner. Coincident exposure to sidestream CS strongly suppressed EOS induced by both HDM and OVA, but this was independent of the α7 genotype. These results suggest a modulatory role by α7 on EOS that is both antigen and cell specific and that is distinct from EOS suppression produced by CS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical statement.

Mice were housed and used for this study in accordance with protocols approved in advance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Utah (Protocol No. 12-06001). In all cases animals were maintained according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Each experiment used groups of three to five mice that were age (4–6 mo), sex, and strain matched. The α7G and α7E260A:G mouse lines have been described in detail elsewhere (7–10). Briefly, a bicistronic IRES-tauGFP reporter cassette was introduced into the 3′ end of the Chrnα7 gene using the precision of homologous recombination to produce the α7G mouse in which α7 transcript expression is visualized by coexpression of GFP. To restrict the α7 ion channel permeability to calcium, in the α7G genetic background the pore-lining glutamate residue 260 was converted to an alanine (α7E260A:G) by point mutation using homologous recombination. Mice were sex and age matched and housed four or five animals per cage.

Allergen sensitization and exposure.

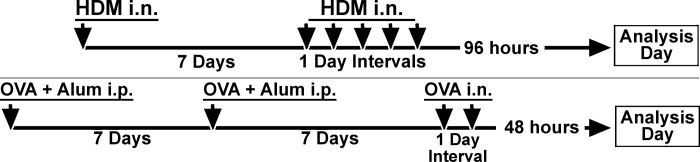

Figure 1 illustrates the sensitization and challenge protocols for both HDM and OVA. Mice were sensitized with OVA via established protocols (6, 15). Briefly, mice were immunized twice (1-wk interval between immunizations) with 200 µg of OVA in an equal volume of alum (intraperitoneal; total volume of 200 µl). One week after the second immunization, mice were challenged with 50 µg of OVA in saline by intranasal inhalation for 2 consecutive days and harvested 48 h after the last challenge. In separate experiments mice were sensitized to HDM (Dermatophagoides sp.; Greer, Lenoir, NC) via an established protocol (3). Briefly, mice were sensitized by administration of 1 µg of HDM in saline via intranasal inhalation (total volume of 40 µl, 20 µl per nostril) and rested for 1 wk. Mice then received 10 µg of HDM (intranasal; total volume of 40 µl, 20 µl per nostril) for 5 consecutive days. These mice were harvested 96 h later. For these studies we determined the optimal response time for eliciting EOS for each of these antigens after the last challenge dose (48 h for OVA, 96 h for HDM). We have found (not shown) that regardless of whether HDM-treated mice were harvested at 24, 48, 72, or 96 h, the α7E260A:G mouse still responds less well than the α7G mouse (see results). Similarly, for OVA-treated mice, at all times tested (24, 48, 72, or 96 h) the α7E260A:G mouse demonstrates an enhanced EOS response compared with the α7G mouse (see results). We chose to analyze EOS and transcripts at the peak of the response for each antigen in order to observe maximal changes between the α7G and α7E260A:G mice. For some experiments, mice were bled just before harvesting to collect plasma for serum measurement of IgE by ELISA per manufacturer’s instructions (Mouse IgE ELISA kit EMIGHE; ThermoFisher, Pittsburgh, PA).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design for allergen [house dust mite (HDM) or ovalbumin (OVA)] sensitizations and challenges used in these experiments. i.n., intranasal; i.p., intraperitoneal.

Isolation of bronchial alveolar lavage fluid and lung epithelial cells.

Cells present in the bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were isolated as described previously (7–10). Briefly, mice were injected intraperitoneally with Avertin before thoracotomy and exsanguinated by severing the abdominal aorta. The trachea was revealed and punctured with an 18-gauge needle followed by an 21-gauge winged infusion set (secured with a suture above the carina) attached to a syringe containing 1 ml of buffer (PBS-2% FBS-0.05% EDTA) that was used to gently flush the lung. The flushing process was repeated five times, and the cells were collected by centrifugation.

Lung epithelial cells were isolated after death as above and perfusion with 10 ml of sterile saline through the right ventricle. Lungs were then lavaged through the trachea, as above, to remove BALF cells. Prewarmed dispase (Dispase II, neutral protease grade II; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) [1 ml of 2 mg/ml (1.8 units/ml)] in Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS)-50 mM HEPES was then infused via the trachea into the lungs. Low-melting-point agarose (1 ml, 1% in DPBS) (ThermoFisher) was then infused via the trachea, and ice was placed on the inflated lungs to solidify the agarose and maintain the dispase in situ. After 2 min the inflated lungs were removed from the chest and dissected away from other tissue such as trachea, thymus, and heart. Lungs were placed in 5 ml of prewarmed dispase (2 mg/ml in DPBS-50 mM HEPES) for 10 min, gently teased apart, passed through a 70-μm cell strainer (gently massaged through), and incubated again for another 10 min in 10 ml of DNase-DMEM-HEPES (deoxyribonuclease I, type II-S; Millipore/Sigma). Cells were then passed through a 40-μm cell strainer into a 50-ml conical tube and centrifuged (1,100 rpm for 10 min, 4°C). Red blood cells were lysed (Invitrogen/ThermoFisher, Pittsburgh, PA), and cells were counted. These cells were then incubated with anti-CD45 antibody conjugated with magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) and separated with an AutoMacs (Miltenyi Biotech). Cells not collected on the magnetic beads (CD45−) were then stained to determine their purity with fluorochrome-labeled anti-CD326 (epCAM) antibody, anti-CD45 antibody, and anti-CD31 (endothelial cell marker). Typically, 98% of cells are CD326+, CD45−, and CD31−.

Flow cytometry.

Methods of flow cytometry (FC) were described in detail previously (7–10). In summary, BALF cells were washed and resuspended (0.5–1 × 106 cells) in 200 µl of FACS staining buffer (PBS, 2% BSA, 0.05% EDTA, serum albumin 0.1%; 4°C), Fc receptors were blocked, and antibodies to CD45, CD11c, CD11b, SiglecF, CD4, CD8, and/or Gr1 were added as previously described (7, 10). Thirty thousand live nucleated cell events were collected for each sample (Accuri cell cytometry system), and the data were analyzed (CFlow Software, Ann Arbor, MI). To correct for high AM autofluorescence in CS samples (9), FC attenuation correction filters [FL1 (CD144), FL2 (CP148), FL3 (CP164), and FL4 (CP165)] were used. Nevertheless, in some cases significant autofluorescence limited additional cell characterization.

Cigarette smoking.

As described previously (9), mice were exposed 5 days/wk for 4 mo to sidestream CS in a Teague smoking chamber with University of Kentucky Agricultural Research program reference cigarettes (3RF4). This was standardized to 25–50 cigarettes per session to obtain total suspended particulates of 150 mg/m3. This required ~225 min of exposure that was initiated at 8:00 AM. Control mice were exposed to room air. This method produces average serum cotinine levels (ELISA kit; Calbiotech) of 10–14 ng/ml when measured 18 h after the most recent CS treatment. Sensitization to OVA or HDM was initiated after 4 mo of CS exposure, and CS was maintained throughout the sensitization and challenge periods. Lungs were harvested after their last exposure and at the appropriate time for the allergen (48 h OVA, 96 h HDM).

Lung histology.

For histological examination at least five α7G or α7E260A:G lungs (right/large lobe) were harvested 48 h after OVA challenge or 96 h after HDM and were prepared with paraformaldehyde gravity inflation and embedded and sectioned (5–10 μm) as described previously (10). Sections were stained with standard hematoxylin and eosin methods or Giemsa staining (per manufacturer’s instructions; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Images were captured in brightfield with a CCD camera and compiled in Photoshop CS5.

RNA transcript measurement.

Transcript expression was quantitated with PCR profiling arrays or RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) as described previously (7, 9, 10). For each mouse, BALF was lavaged to collect CD11c+ cells (AM), and the distal epithelial cells were then enriched (CD45− and CD31−) with successive magnetic bead separation (purity >97%). Epithelium was measured with RNA-Seq (Illumina platform) or for AMs interrogation of inflammatory and chemokine genes with the RT2-Profiler PCR-array (PAMM-011Z; Qiagen). As previously described (9, 10), reads were aligned to the NCBI37/mm9 mouse genome with STAR and read counts from protein coding sequences (CDS) were summarized with the htseq-count script and mouse GENCODE version M1 annotation. After filtering out transcripts encoding immunoglobulins, histocompatibility genes, and hypothetical genes with an Ensembl GM prefix, CDS read counts were analyzed for differential expression with the edgeR Bioconductor package (1). Library size per sample averaged 10.5 million read counts (range 7.8–16.4 million). Read counts were normalized with the TMM method and filtered to remove low-count genes, requiring a count per million (CPM) threshold value of 5 in at least four samples. This reduced the total number of CDS transcripts from 18,229 to 11,240 genes. The design matrix and dispersion estimates were fit to a linear model with the edgeR glmFit function, and differential expression was tested with the glmTreat function between treated and control samples relative to a fold change threshold of 2. Gene-level results were displayed as mean-difference plots, with log fold change for each gene plotted against the average abundance in log2 CPM with the Glimma package (33). Database resources such as GeneMANIA (Ref. 37, using Max resultant genes or attributes and network weighted to Biological process based) and PASTAA (Ref. 28, using Ensembl_46; default calculation) were applied to predicted possible physical and coexpression interactions. RNA was reserved for quantitative TaqMan real-time quantitative PCR (Applied Bioscience/ThermoFisher) confirmation of for the following transcripts: Ccl11 (Mm00441238_m1); Ccl24 (Mm00444701_m1); and routine screening (not shown) for IL-1α (Mm00439620_m1), IL-1β (Mm00434228_m1), IL-4 (Mm00445259_m1), IL-12 (Mm01288989_m1), IL-13 (Mmoo434204_m1), Ccl2 (Mm00441242_m1), and TNF-α (Mm00443258_m1).

RESULTS

Eosinophilia induced by HDM is positively modulated by α7 and suppressed by CS.

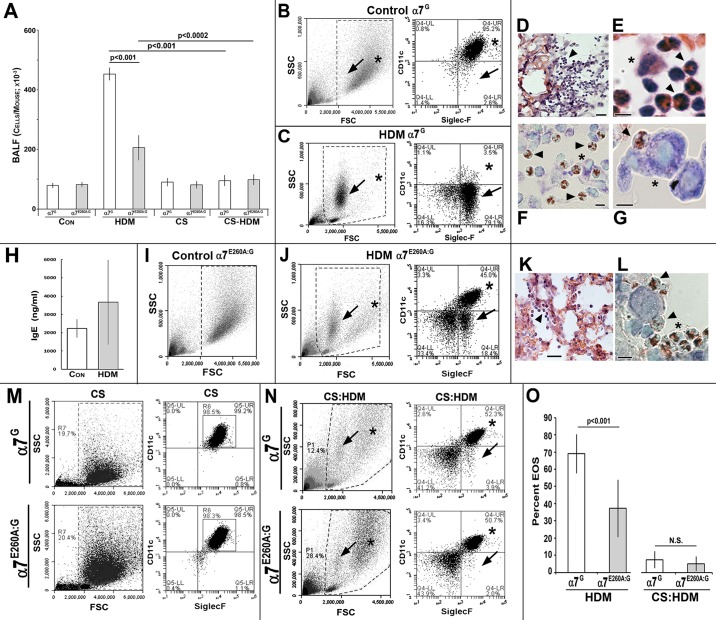

EOS was induced in two mouse models of allergic responsiveness (materials and methods): HDM (Fig. 2) or OVA (Fig. 3). Sets of both α7G (control, normal α7 function) and α7E260A:G (defective signaling through α7) mice were used to compare their respective optimal responses to allergen. Also included were mouse groups first exposed to sidestream CS (CS exposure for 4 mo; see materials and methods and Ref. 9) before antigen sensitization and challenge. For HDM, after intranasal sensitization and challenge (n = 10 total mice, 2 independent trials; male and female) the BALF contained a large increase in total cells in α7G mice but significantly fewer cells in α7E260A:G mice (Fig. 2A). In mice receiving chronic CS the total BALF cell number was equivalent to non-CS (control) samples, and this was not significantly altered after HDM sensitization and challenge. The phenotype of the isolated BALF cells was confirmed with FC and marker-specific antibodies. The majority of BALF cells from control mice were AMs, as revealed by their characteristically larger size (greater forward scatter) and mixed granularity (side scatter) and by staining with antibodies to both the CD11c and SiglecF surface markers (Fig. 2B). Mice that received HDM sensitization only (no challenge doses) or received challenge doses only (not previously sensitized with HDM) did not show an increase in BALF cells or EOS infiltration into BALF (not shown). In BALF preparations from HDM-sensitized mice 96 h after final challenge, the α7G BALF cell composition changed substantially. Now the dominant BALF cell population was of relatively smaller size and high granularity that marker analysis confirmed as EOS (CD11c−/SiglecF+; Fig. 2C). At this time, on average 70% of the total cells in BALF were EOS and 5% were AMs. Also present in small numbers were T cells [CD4+ (4%) and CD8+ (10%)], granulocytes (Gr1+; 3–5%), and few (if any) CD11b+ cells (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Modulation of house dust mite (HDM)-induced eosinophilia (EOS) by nicotinic receptor α7 (α7). A: average bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) total cell number of α7G or α7E260A:G lungs subsequent to sensitization and challenge with HDM before or after exposure to sidestream cigarette smoke (CS) exposure. B: flow cytometry (FC) scatterplot (left, boxed area) and marker analysis (right) of α7G control BALF (non-HDM treated) reveals that >95% are alveolar macrophages (AMs) (CD11c+/SiglecF+; asterisks). Smaller granular cells (CD11c−/SiglecF+, arrows) were infrequent. SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter. C: FC analysis of α7G BALF 96 h after HDM challenge and increased EOS (>75%). Left: high granularity (SSC) and smaller size (FSC) (arrows). Right: CD11c−/SiglecF+ (arrows). Note reduced proportion of AMs (CD11c+/SiglecF+; asterisks). D–G: histology of α7G lung after HDM confirms the presence of small granular cells (D, arrowhead) in terminal bronchioli and alveolar spaces that are absent from controls (not shown; see Refs. 9, 10). E: at increased magnification the classic size and lobed nuclear appearance of EOS are seen (arrowheads). An AM is also present (asterisk). F: Giemsa-stained eosinophils (red nuclei; arrowheads) and an AM (asterisk). G: increased magnification (Giemsa stained) shows the common EOS (arrowhead) association with an AM (asterisk). Bars, 50 μm (D), 10 μm (E–G). H: quantitation of serum IgE from α7G mice not receiving HDM (Con) and after HDM. I: FC analysis of nontreated α7E260A:G lung BALF. J: α7E260A:G BALF after HDM. EOS (arrows) is identified by size and granularity (left) and marker confirmation (CD11c−/SiglecF+; right). AMs identified by asterisks. K: histology of the α7E260A:G lung after HDM challenge confirms cell infiltrates (EOS, arrowhead). L: Giemsa staining shows accumulation of EOS (red nuclei) mostly along alveolar cell linings (asterisk) and in association with AMs (arrowheads). Bars, 50 μm (K), 10 μm (L). M: FC results of BALF from α7G or α7E260A:G after exposure to CS for 4 mo (see text and Ref. 9). Size and granularity (boxed areas, left) and AM content of >95% (CD11c+/SiglecF+, right) are shown (compare with B and I). N: FC of BALF from CS-treated mice that were sensitized and challenged with HDM. EOS (arrows) and AM (asterisks) are identified. O: average EOS response of each α7 genotype after HDM challenge in either the presence or the absence of CS. CS suppression of HDM EOS is highly significant for both genotypes (P < 0.0001). N.S., not significant (P > 0.05). Error bars in A, H, and O = SEM.

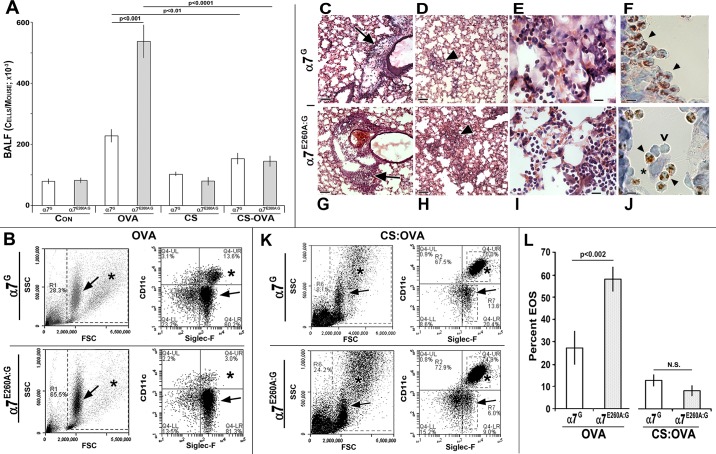

Fig. 3.

Modulation of ovalbumin (OVA)-associated eosinophilia (EOS) by nicotinic receptor α7 (α7). A: bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) average total cell number from control α7G or α7E260A:G (Con) or subsequent to sensitization and challenge with OVA before or after exposure to sidestream cigarette smoke (CS). B: typical EOS of BALF from both α7 genotypes as measured by flow cytometry (FC). Scatterplots (left) and marker analysis (right) show EOS (arrows) and alveolar macrophage (AM; asterisks) content. SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter. C–J: histology of α7 lung after OVA inhalation. The accumulation of small granular cells (EOS) was particularly strong in perivascular regions (C and G; arrows) and in focal clusters in the lung parenchyma (D and H; arrowheads) that are more extensive in the α7E260A:G. Increased magnification shows infiltrating cells distributed differently within alveoli of α7G (adjacent to alveolar walls; E) or α7E260A:G (alveolar spaces; I). F and J: Giemsa stain of EOS (red nuclei, arrowheads). Note different distributions between α7 genotypes and association with AMs (asterisk). Leukocytes not identified by Giemsa staining are also present (v). Bars, 50 μm (C, D, G, and H), 10 μm (E, F, I, and J). K: BALF from CS- and OVA-treated mice. FC of BALF from CS- and OVA-treated lungs shows AMs in scatterplots (left; asterisks) or marker analysis (right). L: average EOS response for each α7 genotype after OVA challenge in either the presence or the absence of CS and statistical significance. N.S., not significant (P > 0.05). Error bars in A and L = SEM.

Lung histology confirmed the cellular infiltrate predicted by FC. After HDM, increased densities of small cells were enriched in the bronchioles, bronchioli, and, to a lesser extent, alveolar spaces (Fig. 2, D–G) of the lung. The α7G control (non-allergen treated) lung histology (not shown) exhibits typical lung morphology and no evidence of EOS cell infiltrate (see Refs. 7, 9, 10). At increased magnification the size and nuclear morphology of infiltrating cells were consistent with EOS (Fig. 2E), which was confirmed with Giemsa stain (Fig. 2F). Eosinophils are also commonly found in association with AMs (Fig. 2G), which are identified as large cells with light blue nuclei after Giemsa staining.

After HDM sensitization and challenge IgE levels can increase, but unlike in humans this is not necessarily specific to HDM (19). The results of serum IgE levels quantitated in six α7G mice before or after HDM sensitization and challenge showed a trend toward increased levels, but it was not statistically significant (Fig. 2H). Thus in this experimental design system the response to HDM was accompanied by only a weak increase in IgE levels at this time.

To determine whether α7 receptor signaling modulates the EOS response to HDM, groups of α7G (control) or α7E260A:G mice (age and sex matched, 4 or 5 male or female mice per experiment) were sensitized and subsequently challenged with HDM (materials and methods). BALF was collected at 96 h, and the average number of cells was calculated. Although elevated above no HDM treatment, the number of cells recovered from the α7E260A:G lung BALF was reduced relative to the control α7G response (Fig. 2A). Sex had no impact on the result (not shown). The α7E260A:G cell composition of BALF from non-HDM-treated mice was similar to that from α7G control mice (compare Fig. 2I to Fig. 2B and see Refs. 7, 9, 10), and after HDM sensitization and challenge there was an increase in EOS (CD11c−/SiglecF+; Fig. 2J). However, this increase was substantially reduced in the BALF from α7E260A:G compared with α7G HDM-sensitized and challenged mice (Fig. 2J vs. Fig. 2C). Histological analysis confirmed these infiltrating cells to be mostly eosinophils (Fig. 2K and Giemsa stain in Fig. 2L), and their reduced number in the α7E260A:G mouse is evident (Fig. 2K). Interactions between EOS and AMs were again observed (Fig. 2L). Quantification of the results (Fig. 2O) confirmed that EOS in the BALF of control α7G mice was substantially elevated (average 70%) compared with α7E260A:G mice (average 37%). At this time (96 h after challenge) cell infiltrates of other types including CD4 and CD8 T cells, granulocytes, and macrophages (CD11b+) did not differ between α7 genotypes (not shown). Thus, in response to HDM, normal α7 signaling favors EOS accumulation in the lung, whereas impaired α7 signaling results in reduced EOS.

As noted above, a widely reported but controversial finding is that CS exposure can suppress many allergic responses. Because nicotine is a major component of tobacco products, especially cigarettes, suppression of inflammatory signaling acting through α7 is possible. To determine whether CS exposure modifies HDM-induced EOS, groups of mice (n = 10) from both α7 genotypes were exposed to sidestream CS for 4 mo (materials and methods and Ref. 9) before HDM sensitization and challenge. FC results examining BALF show that CS increases the size and granularity of AM (CD11c+/SiglecF+) but not their relative numbers regardless of α7-genoytpe (Fig. 2M; Ref. 9). Upon sensitization and challenge with HDM, CS-exposed mice show a significantly decreased EOS response compared with nonexposed α7G mice, and thus this effect occurs independent of α7 genotype (Fig. 2N; quantitated in Fig. 2O). Therefore, the more subtle modulation of the allergen response by α7 is absent in CS-exposed mice, where it is likely overwhelmed by other agents (also see Ref. 9).

Eosinophilia induced by ovalbumin is negatively modulated by α7 and suppressed by CS.

Since normal α7 signaling promotes increased HDM-induced EOS, as suggested by the α7E260A:G decreased EOS response, we determined whether this result can be generalized to other allergy-associated EOS responses. To test this, the well-characterized model of allergic sensitization to OVA was used. Control α7G or α7E260A:G mouse groups (age and sex matched, 4 or 5 male or female mice per experiment) were sensitized to OVA and then challenged (intranasal; materials and methods). At 48 h after challenge (optimal cellular response; not shown), the cell numbers in BALF increased in both α7 genotypes after OVA, but unlike HDM this increase was significantly greater in the α7E260A:G mice (2- to 3-fold increase, significance of P < 0.001; n = 24 per group; Fig. 3A). FC scatterplots and marker analysis again confirm that the dominant change in BALF is increased EOS (Fig. 3B), especially in the α7E260A:G mice. Histology shows that after OVA the lung landscape is dominated by EOS (Fig. 3, C–J), but these cells were highly concentrated in perivascular aggregates (Fig. 3, C and G) and formed prominent focal accumulations in more distal alveoli (Fig. 3, D and H). At increased magnification it can be seen that the α7G cell infiltrates tend to collect near alveoli linings, but they are more randomly spread throughout the alveolar space in α7E260A:G (Fig. 3, E and I). Similar to HDM, eosinophils (as confirmed by Giemsa stain; Fig. 3, F and J) are often in association with AMs (large cells with light blue nuclei; Fig. 3J). Some cells of size similar to eosinophils do not exhibit Giemsa nuclear staining (red). These could be a small but significant population of CD4+ T cells that in FC analysis of BALF is on average 2.4% for α7G vs. 6.8% for α7E260A:G (not shown). Other cell types such as granulocytes did not differ quantitatively between α7 genotypes (not shown). The quantitation of α7-dependent change in EOS is summarized in Fig. 3L, left. In α7G BALF the average is 27 ± 8% (n = 23 mice) vs. 59 ± 7% in α7E260A:G BALF (n = 24). Thus the impact of α7 on lung EOS after challenge to either OVA or HDM was robust, but it promotes EOS to HDM (decreased in the α7E260A:G) and just the opposite after OVA challenge (increased in the α7E260A:G). This striking result strongly supports the conclusion that normal α7G function can strongly modulate the EOS component of an allergic response, but it does so through mechanisms specific to the allergen.

The impact of long-term exposure to CS (4 mo) was to decrease OVA-induced cell infiltration into the BALF (Fig. 3K), as quantitated in Fig. 3L. This is consistent with other reports of suppression by CS exposure of the inflammatory response to OVA in the mouse model (7). Thus CS exposure diminished the EOS response to both OVA and HDM and did so in an α7G-α7E260A:G genotype-independent manner.

Allergen-specific modulation by α7 of lung transcriptional responses.

To examine how the striking inverse modulation of EOS by α7 occurs, transcriptional responses by lung epithelium and AMs to HDM vs. OVA were measured. EOS recruitment and retention in response to an allergen/antigen challenge is mediated by the local tissue environment (12, 14, 31) including the cells of immune (AMs) and epithelial origin (11, 12, 16, 35). In the mouse lung α7G is expressed by at least AM, club, and ATII cells, where it controls robust inflammatory responses to endotoxin (LPS); however, LPS does not elicit lung EOS (7, 9, 10). To examine transcriptional responses, parallel cages of five mice of both α7 genotypes were sensitized and challenged with either OVA or HDM, and AMs (CD11c+; collected from BALF) or enriched lung epithelial cells (CD45−) from distal lung (materials and methods) were harvested for RNA isolation after challenge with HDM (96 h) or OVA (48 h). Quantitative RT2-PCR profiling arrays were used to focus on a subset of chemotactic and inflammatory gene expression profiles from AMs (BALF cells, CD11c+), and RNA-Seq was used to examine global gene expression profiles in distal lung epithelium (materials and methods).

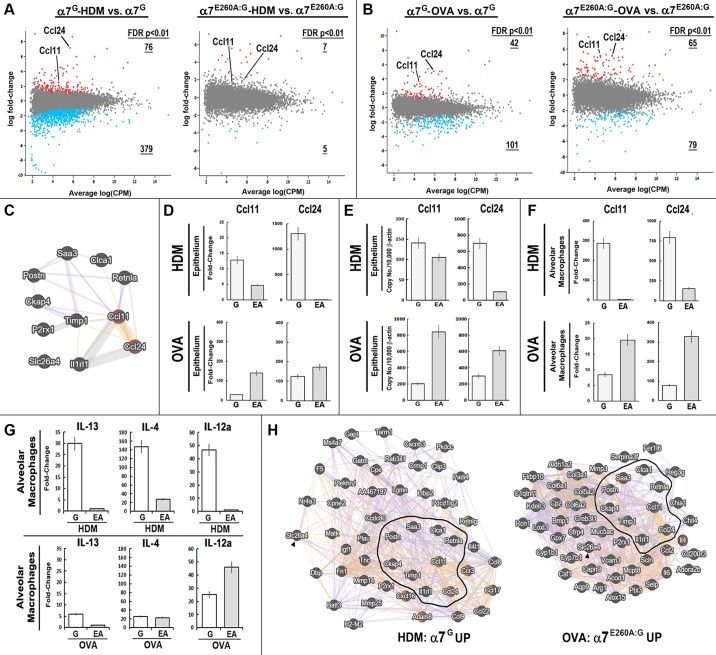

RNA-Seq measurements of lung epithelium after HDM revealed only modest changes in overall gene expression between α7G and α7E260A:G cells (see also Ref. 24). Supplemental Table S1 lists all genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) of P < 0.05 (Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the Journal website). For further analysis, a more stringent FDR cutoff of P < 0.01 was applied to identify 76 transcripts selectively increased in the α7G mice and 379 that decreased relative to the non-HDM-challenged control mice (Fig. 4A). A substantial dampening of this HDM-induced epithelial response was evident, with only seven transcripts increasing and five decreasing in the α7E260A:G mice. This indicates that limiting the ability of normal α7 signaling, as in the α7E260A:G lung epithelia, is an important component and possibly a determinant of the EOS response to HDM. This possibility is supported further by the relative α7-modulated epithelial response to OVA sensitization and challenge. The epithelial transcriptional response for those genes exhibiting the preferred FDR cutoff of P < 0.01 (Supplemental Table S2 lists all transcripts of FDR P < 0.05) again varied with α7 genotype (Fig. 4B). In the α7G mice 42 genes increased and 101 decreased, but for α7E260A:G mice the values were 65 increased and 79 decreased. Thus, in response to OVA, although fewer genes overall were modified in their expression (compared with HDM epithelial response) in the α7G, the α7E260A:G epithelium remained responsive to this allergen.

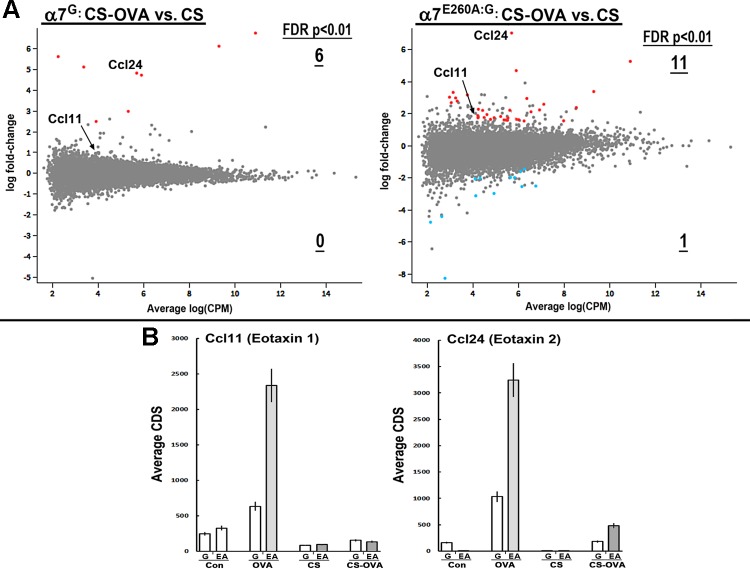

Fig. 4.

Impact of α7 on gene expression associated with house dust mite (HDM) or ovalbumin (OVA) challenges. A and B: RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) results (Glimma plots; materials and methods) showing the results for cigarette smoke (CS)-exposed mice of both genotypes and their response to HDM (A) or OVA (B). Genes exhibiting a significant difference in expression [false discovery rate (FDR) P < 0.05] are highlighted in red (upregulated) or blue (downregulated). Number of genes retained after greater stringency FDR of P < 0.01 is indicated and underlined (see Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Ccl11 and Ccl24 are identified. CPM, count per million. C: diagram generated in GeneMANIA (biological process based, no attributes) shows the relationship between genes that were upregulated in instances of increased eosinophilia (EOS) associated with α7 (α7G-HDM and α7E260A:G-OVA). D–F: α7G (G) or α7E260A:G (EA) Ccl11 (eotaxin1) and Ccl24 (eotaxin2) transcriptional response to either HDM or OVA. The epithelium was measured with RNA-Seq (fold change; D) or quantitative PCR (E). F: RT2-PCR array quantitated alveolar macrophage (AM) response. G: HDM or OVA AM transcription response by IL-13, IL-4, or IL-12α in α7G or α7E260A:G. These transcripts were not detected in the epithelium fraction. Error bars = ±10% of mean. H: diagrams generated with GeneMANIA show interactions among the most responsive gene transcripts increased in response to α7G-HDM and α7E260A:G-OVA. The core group (from C) is outlined or identified with an arrowhead. Genes in red = EOS associated; yellow = cell chemotaxis; blue = extracellular matrix.

To elucidate a set of core candidate pro-EOS signaling transcripts, the gene sets most altered when EOS is increased (i.e., α7G HDM and α7E260A:G OVA) were compared. The results identified 11 genes in common that were upregulated in both data sets (Fig. 4C; GeneMANIA analysis shown). Notable were two genes that are strongly associated with EOS signaling and chemotaxis: Ccl11 (eotaxin1) and Ccl24 (eotaxin2). The fold change in these chemokines in response to these allergens was measured with either RNA-Seq (Fig. 4D) or TaqMan quantitative PCR (Fig. 4E). Ccl11 expression in response to HDM was greatly reduced in the α7E260A:G compared with the α7G, and for Ccl24 the strong induction of this chemokine transcript in the α7G was essentially absent in the α7E260A:G. By comparison, when the allergen was OVA the fold induction of both eotaxins was significantly greater in the α7E260A:G compared with the α7G. These results are consistent with the EOS response measured in BALF (Fig. 3).

A principal cell responding to inhaled allergens is the AM, which also expresses α7 (9). The AM transcriptional response to HDM or OVA also revealed allergen- and α7 genotype-specific responses. In this case, quantitative PCR arrays were substituted for RNA-Seq (materials and methods) to focus on the proinflammatory and pro-EOS response. For the 84 genes measured (materials and methods), the overall HDM response was more robust in the α7G, where 34 genes were selectively increased significantly (>2-fold), but only three genes were elevated in the α7E260A:G. In contrast, the AM response to OVA was 7/84 genes in the α7G and 4/84 in the α7E260A:G. Again, among the changes in expression differences in Ccl11 and Ccl24 were notable (Fig. 4F). The α7G AM Ccl11 and Ccl24 responses to HDM were in both cases substantially greater than in the α7E260A:G, where the fold induction was nearly absent or relatively much smaller. In contrast, the AM response to OVA produced greater induction of both Ccl11 and Ccl24 in α7E260A:G AMs. Thus in terms of α7 modulation of allergen-specific responses, especially as it concerns eotaxins, the impact of normal α7 receptor signaling on HDM in both the epithelium and AMs is to promote Ccl11 and Ccl24 transcription but to suppress eotaxin transcription to OVA allergen.

Cytokines in addition to eotaxins regulate EOS recruitment and accumulation [e.g., IL-4, IL-13, and IL-12 (Fig. 4G; Refs. 6, 12–14, 31)]. One gene implicated in enhanced EOS through promoting EOS infiltration (2) is periostin (Postn), and this transcript exhibited notable α7 genotype-dependent changes in expression (see Fig. 4C and Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Postn was strongly induced in the epithelium of HDM α7G and OVA α7E260A:G (albeit to varying degrees). Additional cytokines were strongly induced by α7G AMs in response to HDM (Fig. 4G) but were essentially absent in the α7E260A:G. The AM response to OVA was substantially different. IL-13 was induced to a greater extent in the α7G than the α7E260A:G (almost 5-fold). IL-4, although only weakly induced, was not different between α7 genotypes (although it was selectively induced in the α7G epithelium; see Supplemental Table S2). IL-12α was strongly induced, and this was almost twofold greater in the α7E260A:G AM. These results confirm that AMs are responsive to both OVA and HDM, but the α7 impact is strongly biased toward enhancing pro-EOS signals to HDM. In response to OVA the role of α7 is more complex, although overall there is a strong trend in suppression of epithelial and AM eotaxins but less so for IL-4 or IL-13. Thus, again α7 impacts on the response to an allergen challenge through mechanisms that are strongly conditional on the identity of the allergen. These results suggest that other coincident interactions, such as with the epithelium, or other factors not measured here also impact on AM in addition to normal α7 function to determine final outcomes.

An extended examination of the α7-associated epithelium transcriptional relationships associated with increased EOS (FDR < 0.01; α7G HDM vs. α7E260A:G OVA) is illustrated with GeneMANIA (Fig. 4H). In each case the 11 increased genes (from Fig. 4C) provide the core for this analysis. Selectively increased transcripts associated with α7G HDM were grouped as “eosinophil migration” (FDR = 5.5e-4) and “positive regulation of cell motility” (FDR = 5.5e-4). The α7G HDM response also includes Ccl17 and Ccl22, whose expression is associated with EOS in human airway epithelium and AM hyperresponsiveness and allergic lung diseases (17). A similar response is also measured in AMs, where the strong induction is essentially absent in α7E260A:G mice (not shown). Finally, this gene group exhibits an enrichment of gene transcripts associated with NF-κB (PASTAA; FDR = 6.4e-05). Aside from the core transcripts (which are outlined in Fig. 4H), α7E260A:G OVA-treated epithelium exhibits a group of transcripts different from those associated with the α7G HDM EOS response. This includes additional genes associated with “eosinophil migration” (FDR = 9.8e-5) such as IL-4 and Ccl2. Also disproportionally increased were IL-6, Muc5a/c, and genes associated with “extracellular matrix” (FDR = 4.3e-5) including fibrillar matrix assembly (e.g., Col5a, Col3a1). The genes in the OVA α7E260A:G RNA are also enriched for those regulated through C/Ebpα (PASTAA FDR = 4.0e-6), which has been previously linked to α7 and lung epithelium gene regulation (7, 9, 10). At present no common features among genes decreased in expression in the samples with the greatest increase in EOS have been identified (not shown; see Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Finally, HDM can contain LPS as a component of the allergen mixture (13). This is important since α7 is a well-known modulator of endotoxin responsiveness and the level of endotoxin in HDM has been reported to be inversely proportional to HDM sensitization and development of asthma (4). However, this does not appear to be a major aspect of the responses being measured, since the results from comparison of gene alterations induced by HDM and intranasal LPS [as reported previously (10)] revealed few if any significant α7-modulated LPS-associated shifts in transcriptional responses (not shown).

CS inhibits OVA epithelial pro-EOS signaling independent of α7 genotype.

As shown in Fig. 3, the EOS response to OVA challenge was substantially increased in the α7E260A:G mouse, but this was strongly suppressed by CS in both α7 genotypes. This offers an opportunity to determine gene expression in the lung epithelium in the presence of CS and how this relates to EOS recruitment. OVA was selected as the allergen for this analysis because it induces the most robust EOS response to allergen, it differs significantly between α7 genotypes, and the response appears most robustly driven by epithelial cells. Mouse groups of each α7 genotype were established and subjected to CS exposures as described in materials and methods. The mice were then sensitized and challenged with OVA, and 48 h later the distal lung epithelium was harvested and the gene expression profile examined by RNA-Seq. The results (Fig. 5A) show that overall CS strongly suppressed gene transcriptional activation in response to OVA and this was α7 genotype independent. The genes for each α7 genotype that were increased (fold change) to OVA in CS-treated mice are listed in Supplemental Table S3. The normal Ccl11 response to OVA was completely abolished in CS-exposed mice, but Ccl24 remained elevated. However, upon examination of the actual transcript number (Fig. 5B), although there was an increase in terms of fold change, the absolute expression of this transcript in both α7 genotypes was decreased quantitatively approximately sevenfold. Thus the presence of some residual EOS in the CS-exposed OVA-treated mice could still be due to the increase in Ccl24 after OVA, although this possibility will require additional evaluation. What does seem clear is that the results strongly favor the actions of CS in this model of allergic EOS being independent of those mechanisms sensitive to α7.

Fig. 5.

Cigarette smoke (CS) suppresses transcriptional responses by distal lung epithelium to ovalbumin (OVA). A: RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) results showing results for CS-exposed mice of both genotypes and their response to OVA (Glimma plots; materials and methods). Genes exhibiting a significant difference in expression [false discovery rate (FDR) P < 0.05] are highlighted in red (upregulated) or blue (downregulated), and the number with an increased stringency of FDR of P < 0.01 is indicated and underlined. Ccl11 and Ccl24 are identified. CPM, count per million. B: average protein coding sequence (CDS) values from RNA-Seq for the individual responses. G, α7G; EA, α7E260A:G. Error bars = ±10% of mean.

DISCUSSION

The accumulation of lung eosinophils is a hallmark of airway hyperresponsiveness and related pathologies including asthma. Because EOS often corresponds with disease severity, understanding the cellular mechanisms in the lung leading to the recruitment and accumulation of these cells is of immediate importance. This study reveals the participation of normal endogenous α7 function in antigen- and cell-specific mechanisms that modulate EOS severity. This would also be expected to be sensitive to exogenous ligands such as nicotine that, depending upon concentration and duration of exposure, could promote receptor activation and/or desensitization-inactivation (23). For both allergens the common and most prominent modulatory impact by α7 was on eotaxin expression. The response to HDM was greatest through changes in AM-associated signaling (possibly NF-κB; see Refs. 9, 10) that strongly promotes EOS. This is also consistent with other reports (36) in which the α7-knockout mouse exhibited a reduced response to cockroach antigen. The α7-associated changes of cell transcriptional signaling in response to OVA were much more evident in the epithelium and less so in the AM response, where changes to C/Ebpα network signaling were suggested. In addition to allergen-dependent alterations in EOS and eotaxin expression, there were also impacts on the overall proinflammatory state (decreased), profibrotic gene expression (increased, particularly OVA), and enhanced transcript expression from genes often associated with reduced inflammatory responses (22) such as Arg1 and Chi3l3 (not shown; but see Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Altered EOS has been associated with decreased inflammatory responses (e.g., Ref. 18), which again indicates the importance of placing the impact by α7 into a cell-specific signaling response that in turn may promote or antagonize EOS depending upon the initiating allergen. These results also lead to apparent contradictions between the α7 response and the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (e.g., Ref. 36). Our findings support the role of α7 as a modulator of inflammatory and allergen responsiveness that can assume several roles depending upon the local cell-specific environment. For example, there can be direct modulation of inflammatory gene expression or an inflammatory response to LPS, as in the α7E260A:G mouse, due to changes in to epithelial signaling of inflammatory cell migration and infiltration [e.g., LPS (7)]. Consequently, the view of α7 as a simple mediator of the anti-inflammatory component of the nicotine response is oversimplified.

Another finding addresses the many contradictory reports on the impact by CS on allergic airway inflammatory phenotypes noted in introduction. Suppression of EOS following OVA sensitization in mice (e.g., Ref. 20), as well as reduced EOS in sputum of smoking asthmatic subjects (32), has been suggested to reflect an impact by CS nicotine on inflammatory processes that promote EOS. We find that CS exposure strongly reduced the EOS response to HDM or OVA in both α7G and α7E260A:G mice. This was accompanied by a near-complete absence of local cell transcriptional responsiveness expected in the absence of CS, including diminished Ccl11 expression. This result strongly argues that CS acts largely independently of nicotine through more nonspecific processes to suppress overall responsiveness to allergen challenge. Of note was that one of the few genes to maintain elevated expression in response to OVA was epithelial Ccl24, albeit this was reduced substantially relative to the no-CS response. Because CS strongly suppresses EOS, this indicates that Ccl24 is still likely to be important to this response, but alone this seems insufficient to promote the observed EOS. Protein measurements in addition to analyses of the local vs. the more extended immunological response (e.g., bone marrow or other cell types) will be necessary to clarify this relationship. Also, because α7 does not appear to be a principal component of the CS-EOS response mechanism, it will be necessary to examine the impact of other agents including particulates, hypoxia, and assorted noxious compounds that likely overwhelm the more precise impact on cell signaling initiated through nicotine (9). What becomes an important consideration and is currently being evaluated is how nicotine delivered independently of CS, such as through the growing use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (“vaping”), will impact on EOS in these models of allergen response and whether the target is α7 associated.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Grant 1BX001798 (to L. C. Gahring) and National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL-135610 (to L. C. Gahring and S. W. Rogers) and 5P01-CA-098262 (to R. B. Weiss).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.C.G. and S.W.R. conceived and designed research; E.J.M. and D.M.D. performed experiments; L.C.G., E.J.M., D.M.D., R.B.W., and S.W.R. analyzed data; L.C.G., R.B.W., and S.W.R. interpreted results of experiments; L.C.G. and S.W.R. prepared figures; L.C.G. and S.W.R. drafted manuscript; L.C.G., R.B.W., and S.W.R. edited and revised manuscript; L.C.G., R.B.W., and S.W.R. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Tables S1-S3 - .xlsx (137 KB)

TABLE S1. Selective α7-genotype impact on epithelium gene expression to HDM. Epithelial gene (CDS is >200, see Methods) response to HDM as measured using RNA-Seq values (edgeR Bioconductor package). Dotted line separates genes with a FDR p<0.05 and p<0.01 for either increased or decreased transcripts.

TABLE S2. Selective α7-genotype impact on epithelium gene expression to OVA. Epithelial gene response to OVA as measured using RNA-Seq values (CDS is >200, edgeR Bioconductor package, see Methods). Dotted line separates genes with a FDR p<0.05 and p<0.01 for either increased or decreased transcripts.

TABLE S3. CS impact on epithelium gene expression response to OVA. Epithelial gene response to OVA in CS-exposed mice of both α7 genotypes as measured using RNA-Seq values (CDS is >200, edgeR Bioconductor package, see Methods). Dotted line separates genes with a FDR p<0.05 and p<0.01 for either increased or decreased transcripts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders S, McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Okoniewski M, Smyth GK, Huber W, Robinson MD. Count-based differential expression analysis of RNA sequencing data using R and Bioconductor. Nat Protoc 8: 1765–1786, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, McBride M, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Chang G, Stringer K, Abonia JP, Molkentin JD, Rothenberg ME. Periostin facilitates eosinophil tissue infiltration in allergic lung and esophageal responses. Mucosal Immunol 1: 289–296, 2008. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botelho FM, Llop-Guevara A, Trimble NJ, Nikota JK, Bauer CM, Lambert KN, Kianpour S, Jordana M, Stämpfli MR. Cigarette smoke differentially affects eosinophilia and remodeling in a model of house dust mite asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 45: 753–760, 2011. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun-Fahrländer C, Riedler J, Herz U, Eder W, Waser M, Grize L, Maisch S, Carr D, Gerlach F, Bufe A, Lauener RP, Schierl R, Renz H, Nowak D, von Mutius E; Allergy and Endotoxin Study Team . Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its relation to asthma in school-age children. N Engl J Med 347: 869–877, 2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brusselle GG, Maes T, Bracke KR. Eosinophils in the spotlight: eosinophilic airway inflammation in nonallergic asthma. Nat Med 19: 977–979, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daubeuf F, Frossard N. Eosinophils and the ovalbumin mouse model of asthma. Methods Mol Biol 1178: 283–293, 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1016-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enioutina EY, Myers EJ, Tvrdik P, Hoidal JR, Rogers SW, Gahring LC. The nicotinic receptor alpha7 impacts the mouse lung response to LPS through multiple mechanisms. PLoS One 10: e0121128, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gahring LC, Enioutina EY, Myers EJ, Spangrude GJ, Efimova OV, Kelley TW, Tvrdik P, Capecchi MR, Rogers SW. Nicotinic receptor alpha7 expression identifies a novel hematopoietic progenitor lineage. PLoS One 8: e57481, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gahring LC, Myers EJ, Dunn DM, Weiss RB, Rogers SW. Lung epithelial response to cigarette smoke and modulation by the nicotinic alpha 7 receptor. PLoS One 12: e0187773, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gahring LC, Myers EJ, Dunn DM, Weiss RB, Rogers SW. Nicotinic alpha 7 receptor expression and modulation of the lung epithelial response to lipopolysaccharide. PLoS One 12: e0175367, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi VD, Vliagoftis H. Airway epithelium interactions with aeroallergens: role of secreted cytokines and chemokines in innate immunity. Front Immunol 6: 147, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirota JA, Hackett TL, Inman MD, Knight DA. Modeling asthma in mice: what have we learned about the airway epithelium? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 44: 431–438, 2011. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0146TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacquet A. Innate immune responses in house dust mite allergy. ISRN Allergy 2013: 735031, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/735031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar RK, Foster PS. Modeling allergic asthma in mice: pitfalls and opportunities. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 27: 267–272, 2002. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar RK, Herbert C, Foster PS. The “classical” ovalbumin challenge model of asthma in mice. Curr Drug Targets 9: 485–494, 2008. doi: 10.2174/138945008784533561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Allergens and the airway epithelium response: gateway to allergic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 134: 499–507, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloyd CM, Rankin SM. Chemokines in allergic airway disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 3: 443–448, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4892(03)00069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makita N, Hizukuri Y, Yamashiro K, Murakawa M, Hayashi Y. IL-10 enhances the phenotype of M2 macrophages induced by IL-4 and confers the ability to increase eosinophil migration. Int Immunol 27: 131–141, 2015. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxu090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKnight CG, Jude JA, Zhu ZQ, Panettieri RA Jr, Finkelman FD. House dust mite-induced allergic airway disease is independent of IgE and Fc epsilon RI alpha. Am J Respir Cell Mol 57: 674–682, 2017. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0356OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melgert BN, Postma DS, Geerlings M, Luinge MA, Klok PA, van der Strate BW, Kerstjens HA, Timens W, Hylkema MN. Short-term smoke exposure attenuates ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in allergic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 30: 880–885, 2004. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pease JE, Weller CL, Williams TJ. Regulation of eosinophil trafficking in asthma and allergy. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop 2004: 85–100, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pechkovsky DV, Prasse A, Kollert F, Engel KM, Dentler J, Luttmann W, Friedrich K, Müller-Quernheim J, Zissel G. Alternatively activated alveolar macrophages in pulmonary fibrosis-mediator production and intracellular signal transduction. Clin Immunol 137: 89–101, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picciotto MR, Addy NA, Mineur YS, Brunzell DH. It is not “either/or”: activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog Neurobiol 84: 329–342, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piyadasa H, Altieri A, Basu S, Schwartz J, Halayko AJ, Mookherjee N. Biosignature for airway inflammation in a house dust mite-challenged murine model of allergic asthma. Biol Open 5: 112–121, 2016. doi: 10.1242/bio.014464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robbins CS, Pouladi MA, Fattouh R, Dawe DE, Vujicic N, Richards CD, Jordana M, Inman MD, Stampfli MR. Mainstream cigarette smoke exposure attenuates airway immune inflammatory responses to surrogate and common environmental allergens in mice, despite evidence of increased systemic sensitization. J Immunol 175: 2834–2842, 2005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers SW, Gahring LC. Nicotinic receptor alpha7 expression during tooth morphogenesis reveals functional pleiotropy. PLoS One 7: e36467, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers SW, Tvrdik P, Capecchi MR, Gahring LC. Prenatal ablation of nicotinic receptor alpha7 cell lineages produces lumbosacral spina bifida the severity of which is modified by choline and nicotine exposure. Am J Med Genet A 158A: 1135–1144, 2012. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roider HG, Manke T, O’Keeffe S, Vingron M, Haas SA. PASTAA: identifying transcription factors associated with sets of co-regulated genes. Bioinformatics 25: 435–442, 2009. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg HF, Druey KM. Modeling asthma: pitfalls, promises, and the road ahead. J Leukoc Biol 104: 41–48, 2018. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MR1117-436R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg HF, Phipps S, Foster PS. Eosinophil trafficking in allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 119: 1303–1310, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin YS, Takeda K, Gelfand EW. Understanding asthma using animal models. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 1: 10–18, 2009. doi: 10.4168/aair.2009.1.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stämpfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 9: 377–384, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nri2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su S, Law CW, Ah-Cann C, Asselin-Labat ML, Blewitt ME, Ritchie ME. Glimma: interactive graphics for gene expression analysis. Bioinformatics 33: 2050–2052, 2017. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thatcher TH, Benson RP, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. High-dose but not low-dose mainstream cigarette smoke suppresses allergic airway inflammation by inhibiting T cell function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L412–L421, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00392.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vareille M, Kieninger E, Edwards MR, Regamey N. The airway epithelium: soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 24: 210–229, 2011. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu M, Mukai K, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Thirdhand smoke component can exacerbate a mouse asthma model through mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018 Apr 2018. pii: S0091–6749(18)30516–5. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuberi K, Franz M, Rodriguez H, Montojo J, Lopes CT, Bader GD, Morris Q. GeneMANIA prediction server 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res 41: W115–W122, 2013. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Tables S1-S3 - .xlsx (137 KB)

TABLE S1. Selective α7-genotype impact on epithelium gene expression to HDM. Epithelial gene (CDS is >200, see Methods) response to HDM as measured using RNA-Seq values (edgeR Bioconductor package). Dotted line separates genes with a FDR p<0.05 and p<0.01 for either increased or decreased transcripts.

TABLE S2. Selective α7-genotype impact on epithelium gene expression to OVA. Epithelial gene response to OVA as measured using RNA-Seq values (CDS is >200, edgeR Bioconductor package, see Methods). Dotted line separates genes with a FDR p<0.05 and p<0.01 for either increased or decreased transcripts.

TABLE S3. CS impact on epithelium gene expression response to OVA. Epithelial gene response to OVA in CS-exposed mice of both α7 genotypes as measured using RNA-Seq values (CDS is >200, edgeR Bioconductor package, see Methods). Dotted line separates genes with a FDR p<0.05 and p<0.01 for either increased or decreased transcripts.