Abstract

Cardiac stress testing improves detection and risk assessment of heart disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the clinical gold-standard for assessing cardiac morphology and function at rest; however, exercise MRI has not been widely adapted for cardiac assessment because of imaging and device limitations. Commercially available magnetic resonance ergometers, together with improved imaging sequences, have overcome many previous limitations, making cardiac stress MRI more feasible. Here, we aimed to demonstrate clinical feasibility and establish the normative, healthy response to supine exercise MRI. Eight young, healthy subjects underwent rest and exercise cinematic imaging to measure left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction. To establish the normative, healthy response to exercise MRI we performed a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis of existing exercise cardiac MRI studies. Results were pooled using a random effects model to define the left ventricular ejection fraction, end-diastolic, end-systolic, and stroke volume responses. Our proof-of-concept data showed a marked increase in cardiac index with exercise, secondary to an increase in both heart rate and stroke volume. The change in stroke volume was driven by a reduction in end-systolic volume, with no change in end-diastolic volume. These findings were entirely consistent with 17 previous exercise MRI studies (226 individual records), despite differences in imaging approach, ergometer, or exercise type. Taken together, the data herein demonstrate that exercise cardiac MRI is clinically feasible, using commercially available exercise equipment and vendor-provided product sequences and establish the normative, healthy response to exercise MRI.

Keywords: ergospect, exercise cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, left ventricular function, stress imaging

INTRODUCTION

Exercise stress testing provides important prognostic information for assessing cardiovascular risk and detection of heart disease (4, 16, 19, 20, 39, 42, 54). Combining exercise stress testing with cardiac imaging, such as echocardiography, nuclear imaging, or positron emission tomography, significantly improves diagnostic sensitivity and specificity (6, 27, 29, 35, 60). Accordingly, exercise stress imaging is commonly performed world-wide (12, 14, 15, 52, 62).

Cardiac magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (cMRI) is the clinical gold-standard for assessing cardiac morphology and global systolic function (40, 46, 59). Despite its excellent spatial resolution and unique potential for additional structural and functional quantification (e.g., fibrosis assessment and/or myocardial energetics), cMRI is not currently utilized for cardiac exercise stress imaging. Although many factors may contribute to the underutilization of stress cMRI, the general lack of MR-compatible exercise equipment and inadequate imaging sequences likely play a major role (36).

To overcome these limitations, several investigators have advocated exercising outside of the MRI followed by a brief transition to the scan table and subsequent imaging (1, 2, 18, 30, 32, 44, 45, 56, 58). Under this paradigm, with much familiarization and the use of innovative body molds (to ensure anatomical image registration), image acquisition can be performed within 60 s of peak exercise (45). Marked hemodynamic recovery during the transition from exercise to imaging (18, 30, 32, 44, 45, 58) and the technical training and familiarization required of both the patient and imaging staff to achieve rapid and accurate body placement has prevented wide-spread adoption of this approach. Accordingly, several investigators have focused on MRI-compatible cycle ergometers, which allow patients to exercise inside the bore of the magnet (3, 24, 26, 31, 33, 38, 41, 47, 55, 61). Although several studies have evaluated cardiac output dynamics using velocity-encoding approaches (5, 7, 21, 25, 37, 50, 57, 61), only a few studies have attempted to evaluate ventricular morphology and function (8–10, 23, 24, 31, 34, 38, 43, 47–49, 51, 55), the vast majority of which have utilized a real-time, ungated free-breathing pulse sequence (8–10, 31, 34, 51). Although this latter approach increases overall feasibility by eliminating ECG-gating artifacts, patient breath-holds, and minimizes the impact of chest movement, postprocessing is incredibly complex and time consuming, negating the possibility of “real-time” image reconstruction during the cardiac stress test (and thus real-time physician feedback). Such limitations have also prevented the wide-spread adoption of this approach.

With this background and the goal of making exercise cMRI clinically translatable, the primary aim of this study was to test the feasibility of using a commercially available MR-compatible ergometer, combined with vendor-provided MRI sequences, to assess cardiac morphology and function. To assess the impact of movement on image quality, we compared images acquired during exercise, with images acquired immediately (0–4 s) postexercise. To assess the impact of a prolonged pause between exercise and imaging—similar to that encountered when exercise is performed outside of the bore of the MRI—we compared subject hemodynamics, cardiac morphology, and cardiac function between exercise and following a 60-s pause. A secondary aim of this study was to perform a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis of published studies reporting cardiac volumes during exercise cMRI to establish the normative response.

METHODS

Participants

Eight recreationally active, young, healthy subjects were recruited from the Dallas-Fort Worth community. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were 18–35 yr old, physically active, and had no history of cardiovascular, metabolic, or neurological disease. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to MRI and physical limitations precluding exercise.

All procedures were performed in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration; all participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the University of Texas at Arlington and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Protocol

To address our primary aim, each subject completed three visits. The first visit was used for screening, familiarization with the MRI-compatible ergometer (Ergospect Cardio-Stepper, Ergospect, Austria), and determination of target workload and heart rate for exercise cMRI. The second visit was used to characterize the metabolic cost and hemodynamic differences between supine exercise with our MR-compatible ergometer and upright exercise with a traditional cycle ergometer (Lode Corival, Lode, The Netherlands). The third visit consisted of a resting and exercise stress cMRI.

Supine cardiopulmonary exercise test.

Subjects underwent a supine, incremental maximal exercise test, starting at 15 W at a cadence of 50 revolutions/min and progressing by 15 W every 2 min until volitional exhaustion or significant and continued loss of cadence (≥10 revolutions/min despite verbal encouragement to continue). Heart rate (Polar H1, Polar), expired gas analysis (TrueOne 2400, Parvomedics), and work-rate (Ergospect Cardio-Stepper, Ergospect) were recorded continuously.

Upright cardiopulmonary exercise test.

Subjects underwent an incremental ramped maximal exercise test, starting at 50 W at a self-selected cadence (50–90 revolutions/min) and progressing by 20 W every 2 min until volitional exhaustion. Heart rate (Polar H1, Polar), expired gas analysis (TrueOne 2400, Parvomedics), and work-rate (Lode Corival, Lode) were recorded continuously.

Cardiac MRI.

Imaging was conducted on a Phillips Achieva 3T scanner. Following resting imaging, subjects exercised at the workload determined from study visit 1 required to achieve four metabolic equivalents (4 metabolic equivalents ≈14 ml·kg−1·min−1), the minimal threshold for independent living (53). High resolution long-axis (4-chamber and 2-chamber) and short-axis (midventricular, papillary muscle level) cine images were acquired using balanced fast-field echo at rest, during exercise, immediately (0–4 s) postexercise, and 60 s postexercise (to mimic patient transfer from an external exercise device). Typical image parameters include repetition time = 3.4 ms; echo time = 1.7 ms; flip angle = 45°; acquisition matrix = 195 × 195; field of view = 295 × 295 mm; 8-mm slice thickness; 20–30 phases/cardiac cycle, with 1 slice acquired per breath hold. Breath-hold time ranged between 7 and 9 s at rest and 3–5 s during exercise.

cMRI data were analyzed using commercially available software (CVI42, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging). Left ventricular volumes were calculated by Simpson’s Biplane method using standard 4- and 2-chamber slices, and cross-sectional area was measured in the short-axis plane. All volumes were indexed to body surface area calculated by the Dubois-Dubois formula to account for body size variation (13).

Comprehensive Literature Review

To accomplish our secondary aim, we performed a comprehensive literature review, searching articles on PubMed from 1985 to March 2018 using the search terms “exercise AND cardiac MRI,” hand-searched references, and contacted experts in the field. A priori, we included studies reporting left-ventricular cardiac volumes for healthy controls aged 16–36 to best match our participant inclusion criteria. We extracted mean resting and exercise end-diastolic, end-systolic, and stroke volumes, heart rates, and ejection fractions from study text, tables, and figures (WebPlotDigitizer, v. 4.1, Rohatgi). If data were not readily extractable, authors were contacted directly and asked to provide the missing or unattainable data.

Statistical Analysis

Aim 1: feasibility study.

Dependent variables were confirmed for normality and homoscedasticity using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Changes in cardiac volumes and global left ventricular function from rest to exercise/postexercise were assessed using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Sidak post hoc testing. Hemodynamic and cardiopulmonary data were compared between the supine and upright incremental exercise tests using a paired sample t-test. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24 IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk). All data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise stated, and statistical significance was considered when P ≤ 0.05.

Aim 2: comprehensive literature review.

Previously published results from the literature review were pooled and analyzed by a random-effect analysis to create a single, more precise estimate of the effect size. The rest/exercise correlation was assumed to be moderate (50%; 17). Analysis and graphical presentation were performed in R 3.4.2 using the “metaphor” package (R Core Team 2016, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Effect sizes were calculated using both standardized mean differences (SMD) and weighted mean differences (WMD) between rest and exercise conditions. A SMD of 0.25 was considered as a small effect size, 0.5 as a medium effect size, and 0.8 and higher as a large effect size. Heterogeneity of studies was explored using the Cochrane’s Q test of heterogeneity (P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant). Inconsistency in the results of the studies was assessed by I2, which described the percentage of total variation across studies that was due to heterogeneity. When I2 was ≥ 50%, there was more than moderate inconsistency (11, 28).

RESULTS

Aim 1: Feasibility Study

Eight healthy men and women completed the feasibility study (male/female, 3/5; age, 25 ± 3 yr; body mass index, 22.3 ± 2.7 kg/m2; BSA, 1.62 ± 0.14 m2).

Supine versus upright exercise.

The metabolic and hemodynamic data for both the supine and upright cardiopulmonary stress tests are displayed in Table 1. Peak oxygen consumption was markedly lower during supine exercise compared with upright cycling, reflective of the smaller muscle mass being utilized with the MR-compatible ergometer. Similarly, peak heart rate, peak respiratory exchange ratio, and peak ventilation were also markedly lower. None of the subjects met the criteria for true maximal O2 consumption(V̇o2max) during supine exercise, defined as achieving 1) age-predicted maximal heart rate, 2) respiratory exchange ratio > 1.10, or 3) a plateau in oxygen consumption. In contrast, all of the subjects during the upright cycling ramp test met at least two of these criteria. The primary reason for stopping the supine exercise test was an inability to overcome the change in resistance; none of the subjects reported maximal perceived exertion or breathlessness as a reason for stopping.

Table 1.

Metabolic and hemodynamic comparison between supine and upright exercise

| Parameter | Supine | Upright | Percentage of Upright | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V̇o2peak, ml·kg−1·min−1 | 26 (3) | 39 (5) | 67 (10) | 0.0007 |

| V̇o2peak, l/min | 1.24 (0.35) | 2.31 (0.53) | 67 (10) | 0.0004 |

| Ventilationpeak, l/min | 57 (15) | 106 (24) | 56 (13) | 0.0003 |

| RERpeak | 1.07 (0.06) | 1.23 (0.09) | 87 (6) | 0.0007 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 153 (19) | 188 (9) | 82 (9) | 0.0011 |

Values are means (SD). RER, respiratory exchange ratio; RERpeak, peak RER; Ventilationpeak, peak ventiliation; V̇o2peak, peak oxygen consumption.

cMRI feasibility.

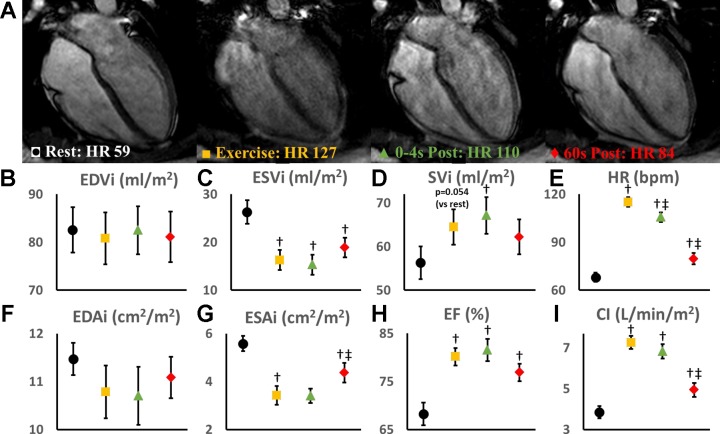

Cardiac imaging was possible during exercise in all of the subjects. None of the subjects reported any discomfort or experienced any adverse events. As expected, image quality was improved postexercise (0–4 s, 60 s), when upper body and chest coil movements were eliminated (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A: representative high resolution cardiac magnetic resonance (cMR) images at rest (black circle), during exercise (yellow square), immediately postexercise (0–4 s, green triangle), and 60 s postexercise (red diamond). Left ventricular (LV) volumes were indexed to body surface area for determining LV end-diastolic volume (EDVi) (B), end-systolic (ESVi) (C), and stroke volume (SVi) (D) and multiplied by heart rate (E) to generate cardiac index (I). LV cavity areas were measured from a mid-short-axis image (papillary muscle level) and indexed to body surface area for determination of end-diastolic (EDAi) (F) and end-systolic (ESAi) (G) cavity areas. Ejection fraction (H) was calculated from the biplane volumes. Data presented as means and SE. †Statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference from rest; ‡statistically significant from exercise. CI, cardiac index; EF, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate.

Both heart rate and stroke volume increased with exercise, resulting in a twofold increase in cardiac index (CI; Fig. 1). The increase in stroke volume was mediated entirely by a reduction in end-systolic volume (ESV), as end-diastolic volume (EDV) was unchanged with exercise. Accordingly, ejection fraction was also significantly increased with exercise.

As compared with imaging during exercise, imaging immediately postexercise had no significant impact on chamber volumes, ejection fraction or CI. In contrast, imaging 60 s postexercise resulted in a significant increase in ESV and a significant decrease in heart rate, ejection fraction, and CI (Fig. 1).

Aim 2: Literature Review and Data Synthesis

Our search produced 1,787 articles; 17 studies reported rest and exercise cardiac volumes. Of the 17 studies, data were extracted from 14 studies (Table 2). One study (33) reported median and interquartile range that could not be used in our synthesis. Two studies (22, 47) were confirmed to have used previously reported data sets and were therefore excluded. When multiple exercise intensities were reported, the exercise intensity closest to that chosen in our feasibility study was reported.

Table 2.

Characteristics of exercise cMRI studies reporting LV volumes

| Study | n, m/f | Age | Resting HR | Image HR | Exercise Intensity | Field Strength | Exercise Type | Image Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present Study | 3/5 | 25 (3) | 67 (8) | 115 (9) | Submax | 3.0T | Supine, Ergospect CardioStepper | Gated, breath-hold, SAX, biplane LAX |

| Claessen 2014(a) (9) | 14/0 | 36 (6) | 66 (7) | 143 (7) | Max* | 1.5T | Supine, Lode MRI cycle | Real-time free-breathe SAX/LAX stacks |

| Claessen 2014(b) (8) | 8/1 | 35 (12) | NR | NR | Max* | |||

| Claessen 2015 (10) | 14/0 | 36 (15) | 56 (8) | 149 (11) | Max | |||

| Gusso 2012 (24) | 4/4 | 25 (4) | 67 (15) | 110 (3) | Submax | 1.5T | Supine, custom MRI cycle | Gated breath-hold SAX stack, 3 LAX |

| Gusso 2012 (23); 2017 (22) | 10/12 | 17 (1) | 75 (14) | 109 (5) | Submax | |||

| La Gerche 2012 (31) | 13/2 | 35 (9) | 59 (14) | 164 (10) | Max* | 1.5T | Supine, Lode MRI cycle | Real-time free-breathe SAX/LAX stacks |

| Lafountain 2016 (31) | 8/8 | 26 (5) | 62 (NR) | 166 (NR) | Max* | 1.5T | Upright, custom MRI treadmill | Ungated, free-breathe SAX stack and biplane LAX slices |

| Lurz 2009 (34) | 5/7 | 33 (29–42) | 74 (3) | 154 (13) | Max* | 1.5T | Supine, Lode MRI cycle, flutter kicking motion | Real-time free-breathe SAX stacks |

| Oosterhof 2005 (38) | 8/6 | 27 (4) | 66 (8) | 121 (8) | Submax | 1.5T | Supine, custom MRI cycle | Turbo field echo planar imaging SAX stack |

| Pinto 2014 (43) | 10/9 | 17 (2) | 70 (10) | 109 (4) | Submax | 1.5T | Supine, custom MRI cycle | Gated breath-hold SAX stack, 3 LAX |

| Roest 2001 (48); 2002 (47) | 8/8 | 18 (2) | 71 (10) | 121 (14) | Submax | 1.5T | Supine, Custom MRI ergometer | Gated breath-hold SAX stack |

| Roest 2004 (49) | 7/7 | 25 (5) | 67 (8) | 122 (8) | Submax | |||

| Schnell 2017(a) (51) | 15/0 | 35 (8) | 59 (12) | 155 (18) | Max | 1.5T | Supine, Lode MRI cycle | Real-time free-breathe SAX/LAX stacks |

| Schnell 2017(b) (51) | 12/3 | 35 (14) | 66 (7) | 150 (12) | Max | |||

| Steding-Ehrenborg 2013 (55) | 20/6 | 30 (9) | 60 (11) | 94 (13) | Submax | 1.5T | Supine, Custom MRI ergometer | Gated breath-hold SAX stack and LAX slice |

cMRI, cardiac MRI; f, female; HR, heart rate; LAX, long axis; T, Tesla. LV, left ventricle; m, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NR, not reported; SAX, short axis; T, Tesla.

Submaximal data used in meta-analysis, see Fig. 2 legend.

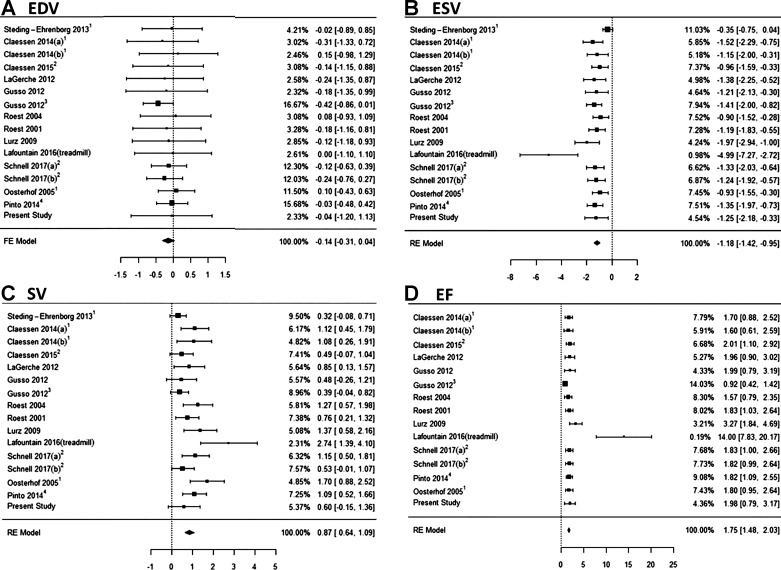

Characteristics of the studies included in our comprehensive data synthesis are displayed in Table 2. The SMD model was used to account for variance in study participants (sex, age, BSA, exercise capacity) and volumetric reporting (standard vs. normalized volumes). By combining these data sets, we were able to evaluate the normal physiological response to supine exercise in 226 healthy subjects. The pooled analysis supports our proof-of-concept data (reported above), showing a marked and significant increase in ejection fraction during exercise compared with rest (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Moreover, we observed no change in left ventricular EDV, with changes in stroke volume being entirely driven by reductions in ESV (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Similarly, the magnitude of change in cardiac output was therefore predominantly driven by changes in heart rate (Table 2). The Q test revealed significant variation in the exercise response to ejection fraction (P = 0.004), ESV (P = 0.007), and stroke volume (P = 0.005), although less than moderate (I2 = 41%, 49%, and 27%). There was no heterogeneity in EDV response (Table 3A).

Fig. 2.

Pooled standardized mean difference [exercise-rest (95% confidence interval)] for left ventricular end-diastolic volume (EDV) (A), end-systolic volume (ESV) (B), stroke volume (SV) (C), and ejection fraction (EF) (D) from the available exercise cardiac magnetic resonance (cMR) studies. Values taken from graphical representations at 1moderate and 2peak intensity exercise. 3Adolescent populations with 4values taken from graphical representations. FE model, fixed effects model; RE model, random effects model.

Table 3.

Effect size, significance, and heterogeneity for pooled analyses

| A. Measure | n | SMD [95% CI] | Significance (H0:SMD = 0) | Q P Value | I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDV, ml | 16 | −0.14 [−0.31, 0.04] | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0 |

| ESV, ml/m2 | 16 | −1.18 [−1.42, −0.95] | <0.0001 | 0.005 | 41 |

| SV, ml/kg | 16 | 0.87 [0.64, 1.09] | <0.0001 | 0.006 | 50 |

| EF, % | 15 | 1.75 [1.48, 2.03] | <0.0001 | 0.006 | 26 |

| B. Measure | WMD | (H0:WMD = 0) | Q P Value | I2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDV, ml | 11 | −0.33 [−0.61, −0.06] | 0.027 | 0.18 | 28 |

| ESV, ml | 11 | −3.51 [−4.11, −2.9] | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 75 |

| SV, ml | 11 | 3.86 [3.07, 4.65] | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 91 |

| EF, % | 15 | 6.12 [5.26, 6.98] | <0.0001 | 0.005 | 95 |

n, number of comparison. 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals; H0, null hypothesis; EDV, end-diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction; ESV, end-systolic volume; SMD, standardized mean difference; SV, stroke volume; WMD, weighted mean difference. SMD calculated by pooling EDV (ESV, SV) for studies reporting measures in ml, ml/m2 (BSA normalized) and ml/kg (normalized to fat-free mass). WMD calculated by pooling studies reporting EDV (ESV, SV) in ml.

Visual inspection of Fig. 2 prompted post hoc analysis to determine if the Lafountain study (2016, treadmill exercise) was a statistical outlier. Based on our model, ~5% of the externally standardized residuals would be expected to exceed the bounds ± 1.96. Externally standardized residuals were calculated for ESV, stroke volume, and ejection fraction as −3.85, 1.92, and 12.24, respectively, indicating the study as a potential outlier. In a sensitivity analysis, removal of Lafountain (2016) from the meta-analysis increased Q test P values (0.08, 0.05, and 0.26) and reduced I2 values (38%, 42%, and 26%) for ESV, stroke volume, and ejection fraction, demonstrating a significant reduction in heterogeneity.

DISCUSSION

The major novel findings of this study are threefold. First, we demonstrate feasibility of exercise stress cMR using a commercially available leg ergometer and vendor-provided product sequences at 3 Tesla. Second, we demonstrate hemodynamic similarities between imaging during and immediately postexercise but marked hemodynamic decline when imaging is delayed for at least 60 s postexercise. Finally, by combining our results with previously published data, we were able to define the normal cardiac response to exercise cMRI.

That cardiac imaging was feasible using a commercially available leg ergometer and vendor-provided product sequences, provides great promise for easy and simple adoption of exercise cMRI to clinical settings. Although we observed a marked improvement in image quality by imaging immediately postexercise, we observed no major differences in cardiac volumes or global left ventricular function between these two conditions. Because inclusion of brief pauses will prolong the exercise stress imaging protocol, we believe imaging during exercise will prove to be the protocol of choice for most clinical sites. Of course, if exercise intensity is increased beyond the submaximal level performed herein, imaging during brief periods of exercise cessation may need to be adopted to overcome the anticipated upper body and chest coil movement. Indeed, as movement artifact increases with higher exercise intensities, spatial resolution may degrade despite consistent imaging parameters. Caution is indeed warranted when interpreting data acquired past 4 s postexercise; however, as our results suggest, prolonged periods of rest following exercise are associated with sharp hemodynamic recovery. Although it may be argued that the rapid hemodynamic recovery observed in this study is reflective of the younger, healthy population studied herein, clinical patients exercised outside of scanner bore and transferred for imaging share a comparable decline in heart rate (44, 45).

Our feasibility data, together with our meta-analysis, demonstrate that the increase in cardiac output during submaximal supine exercise is driven predominantly by an increase in heart rate, with minimal contribution from stroke volume. The data overwhelmingly suggest that healthy subjects have no EDV reserve during supine exercise, despite the expected increase in respiratory and muscle pumps. That this observation is consistent across studies that did not perform breath holds (8–10, 31, 32, 51) argues against intrathoracic pressure (i.e., Valsalva maneuver) mediated reductions in preload. These data must therefore reflect the fact that supine positioning, combined with leg elevation (feet in the ergometer stirrups), produces near maximal EDVs.

That we only observed a small reduction in ESV with exercise was surprising, although consistent with other cMRI studies in healthy populations (8–10, 23, 24, 31, 32, 34, 38, 43, 48, 49, 51, 55). Admittedly, this investigation was focused on submaximal exercise, and thus we cannot extend these ESV findings to higher exercise intensities. Indeed, studies that included higher workloads have reported exercise intensity dependent reductions in ESV (8–10, 31, 33, 51). This interstudy difference likely contributed to the heterogeneity of findings in our meta-analysis for ESV, ejection fraction, and stroke volume. Regardless of exercise intensity, however, the absolute change in ESV remains fairly low. This may reflect the fact that supine exercise with MR-compatible ergometers may not recruit sufficient muscle mass to challenge cardiac output enough to demand greater ESV changes. Compared with conventional upright cycling, our data clearly show blunted metabolic demand, also observed in a prior investigation using a different MR-compatible ergometer (33).

This proof-of-concept feasibility study is not without limitation. First, we limited our data collection to young healthy participants. Future studies are needed to extend these data to clinical populations. Second, spatial resolution was purposely sacrificed to shorten breath-hold time. As a result, the cine images were not sufficient for tissue deformation (i.e., strain) analysis. Inclusion of quantifiable regional wall motion measurements will be an important future addition, especially in clinical populations.

Perspectives and Significance

Taken together, the data herein establish the proof-of-concept that exercise cMRI can be easily adapted to a clinical setting, providing gold-standard noninvasive stress images during exercise. Using commercially available MRI-compatible exercise equipment and vendor-provided product sequences, we were able to successfully characterize the cardiac response to submaximal exercise. By combining our feasibility data with previously published results, we also establish the normative cardiac stress response in over 200 healthy subjects. With this background in place, future studies are needed to adapt this approach in clinical populations.

GRANTS

This project was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HL-136601), the American Heart Association (grant nos. 16SDG27260115, 18PRE33960358, and 18POST33990210), and the Harry S. Moss Heart Trust. Dr. Haykowsky receives support from the University of Texas at Arlington, College of Nursing and Health Innovation, Moritz Chair in Gerontology.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.I.B., M.J.H., and M.D.N. conceived and designed research; R.I.B., T.J.S., W.J.T., M.J.H., and M.D.N. performed experiments; R.I.B., J.W., and M.D.N. analyzed data; R.I.B., T.J.S., J.W., W.J.T., M.J.H., and M.D.N. interpreted results of experiments; R.I.B., J.W., and M.D.N. prepared figures; R.I.B. and M.D.N. drafted manuscript; R.I.B., T.J.S., J.W., W.J.T., M.J.H., and M.D.N. edited and revised manuscript; R.I.B., T.J.S., J.W., W.J.T., M.J.H., and M.D.N. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Orlando Simonetti for providing expert advice on previously published exercise cMR literature.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abd-Elmoniem KZ, Sampath S, Osman NF, Prince JL. Real-time monitoring of cardiac regional function using fastHARP MRI and region-of-interest reconstruction. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 54: 1650–1656, 2007. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.891946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida-Morais L, Pereira-da-Silva T, Branco L, Timóteo AT, Agapito A, de Sousa L, Oliveira JA, Thomas B, Jalles-Tavares N, Soares R, Galrinho A, Cruz-Ferreira R. The value of right ventricular longitudinal strain in the evaluation of adult patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot: a new tool for a contemporary challenge. Cardiol Young 27: 498–506, 2017. doi: 10.1017/S1047951116000810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asschenfeldt B, Heiberg J, Ringgaard S, Maagaard M, Redington A, Hjortdal VE. Impaired cardiac output during exercise in adults operated for ventricular septal defect in childhood: a hitherto unrecognised pathophysiological response. Cardiol Young 27: 1591–1598, 2017. doi: 10.1017/S1047951117000877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balady GJ, Arena R, Sietsema K, Myers J, Coke L, Fletcher GF, Forman D, Franklin B, Guazzi M, Gulati M, Keteyian SJ, Lavie CJ, Macko R, Mancini D, Milani RV; American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research . Clinician’s guide to cardiopulmonary exercise testing in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 122: 191–225, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e52e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bal-Theoleyre L, Lalande A, Kober F, Giorgi R, Collart F, Piquet P, Habib G, Avierinos JF, Bernard M, Guye M, Jacquier A. Aortic function’s adaptation in response to exercise-induced stress assessing by 1.5T MRI: a pilot study in healthy volunteers. PLoS One 11: e0157704, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee A, Newman DR, Van den Bruel A, Heneghan C. Diagnostic accuracy of exercise stress testing for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Clin Pract 66: 477–492, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng CP, Herfkens RJ, Taylor CA, Feinstein JA. Proximal pulmonary artery blood flow characteristics in healthy subjects measured in an upright posture using MRI: the effects of exercise and age. J Magn Reson Imaging 21: 752–758, 2005. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claessen G, Claus P, Delcroix M, Bogaert J, La Gerche A, Heidbuchel H. Interaction between respiration and right versus left ventricular volumes at rest and during exercise: a real-time cardiac magnetic resonance study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H816–H824, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00752.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claessen G, Claus P, Ghysels S, Vermeersch P, Dymarkowski S, LA Gerche A, Heidbuchel H. Right ventricular fatigue developing during endurance exercise: an exercise cardiac magnetic resonance study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46: 1717–1726, 2014. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claessen G, La Gerche A, Dymarkowski S, Claus P, Delcroix M, Heidbuchel H. Pulmonary vascular and right ventricular reserve in patients with normalized resting hemodynamics after pulmonary endarterectomy. J Am Heart Assoc 4: e001602, 2015. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 112: 155–159, 1992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demir OMM, Bashir A, Marshall K, Douglas M, Wasan B, Plein S, Alfakih K. Comparison of clinical efficacy and cost of a cardiac imaging strategy versus a traditional exercise test strategy for the investigation of patients with suspected stable coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 115: 1631–1635, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916. Nutrition 5: 303–311, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferket BS, Genders TS, Colkesen EB, Visser JJ, Spronk S, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MG. Systematic review of guidelines on imaging of asymptomatic coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 1591–1600, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, Berra K, Blankenship JC, Dallas AP, Douglas PS, Foody JM, Gerber TC, Hinderliter AL, King SB III, Kligfield PD, Krumholz HM, Kwong RYK, Lim MJ, Linderbaum JA, Mack MJ, Munger MA, Prager RL, Sabik JF, Shaw LJ, Sikkema JD, Smith CR JR, Smith SC JR, Spertus JA, Williams SV; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American College of Physicians; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons . 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: e44–e164, 2012. [Erratum in J Am Coll Cardiol 63: 1588-1590, 2014.] doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, Arena R, Balady GJ, Bittner VA, Coke LA, Fleg JL, Forman DE, Gerber TC, Gulati M, Madan K, Rhodes J, Thompson PD, Williams MA; American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention . Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 128: 873–934, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b5b44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol 45: 769–773, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90054-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster EL, Arnold JW, Jekic M, Bender JA, Balasubramanian V, Thavendiranathan P, Dickerson JA, Raman SV, Simonetti OP. MR-compatible treadmill for exercise stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 67: 880–889, 2012. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler-Brown A, Pignone M, Pletcher M, Tice JA, Sutton SF, Lohr KN; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Exercise tolerance testing to screen for coronary heart disease: a systematic review for the technical support for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 140: W9–W24, 2004. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, Chaitman BR, Fletcher GF, Froelicher VF, Mark DB, McCallister BD, Mooss AN, O’Reilly MG, Winters WL JR, Gibbons RJ, Antman EM, Alpert JS, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gregoratos G, Hiratzka LF, Jacobs AK, Russell RO, Smith SC Jr; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines) . ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). Circulation 106: 1883–1892, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034670.06526.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Globits S, Sakuma H, Shimakawa A, Foo TKF, Higgins CB. Measurement of coronary blood flow velocity during handgrip exercise using breath-hold velocity encoded cine magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol 79: 234–237, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)89291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gusso S, Pinto T, Baldi JC, Derraik JGB, Cutfield WS, Hornung T, Hofman PL. Exercise training improves but does not normalize left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 40: 1264–1272, 2017. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gusso S, Pinto TE, Baldi JC, Robinson E, Cutfield WS, Hofman PL. Diastolic function is reduced in adolescents with type 1 diabetes in response to exercise. Diabetes Care 35: 2089–2094, 2012. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gusso S, Salvador C, Hofman P, Cutfield W, Baldi JC, Taberner A, Nielsen P. Design and testing of an MRI-compatible cycle ergometer for non-invasive cardiac assessments during exercise. Biomed Eng Online 11: 13, 2012. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heiberg E, Pahlm-Webb U, Agarwal S, Bergvall E, Fransson H, Steding-Ehrenborg K, Carlsson M, Arheden H. Longitudinal strain from velocity encoded cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a validation study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 15: 15, 2013. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heiberg J, Asschenfeldt B, Maagaard M, Ringgaard S. Dynamic bicycle exercise to assess cardiac output at multiple exercise levels during magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 46: 102–107, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henri C, Piérard LA, Lancellotti P, Mongeon FP, Pibarot P, Basmadjian AJ. Exercise testing and stress imaging in valvular heart disease. Can J Cardiol 30: 1012–1026, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327: 557–560, 2003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaarsma C, Leiner T, Bekkers SC, Crijns HJ, Wildberger JE, Nagel E, Nelemans PJ, Schalla S. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive myocardial perfusion imaging using single-photon emission computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and positron emission tomography imaging for the detection of obstructive coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 59: 1719–1728, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jekic M, Foster EL, Ballinger MR, Raman SV, Simonetti OP. Cardiac function and myocardial perfusion immediately following maximal treadmill exercise inside the MRI room. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 10: 3, 2008. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.La Gerche A, Claessen G, Van de Bruaene A, Pattyn N, Van Cleemput J, Gewillig M, Bogaert J, Dymarkowski S, Claus P, Heidbuchel H. Cardiac MRI: a new gold standard for ventricular volume quantification during high-intensity exercise. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 6: 329–338, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.980037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lafountain RA, da Silveira JS, Varghese J, Mihai G, Scandling D, Craft J, Swain CB, Franco V, Raman SV, Devor ST, Simonetti OP. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the MRI environment. Physiol Meas 37: N11–N25, 2016. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/37/4/N11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le TT, Bryant JA, Ting AE, Ho PY, Su B, Teo RC, Gan JS, Chung YC, O’Regan DP, Cook SA, Chin CW. Assessing exercise cardiac reserve using real-time cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 19: 7, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lurz P, Muthurangu V, Schievano S, Nordmeyer J, Bonhoeffer P, Taylor AM, Hansen MS. Feasibility and reproducibility of biventricular volumetric assessment of cardiac function during exercise using real-time radial k-t SENSE magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 29: 1062–1070, 2009. 10.1002/jmri.21762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metz LD, Beattie M, Hom R, Redberg RF, Grady D, Fleischmann KE. The prognostic value of normal exercise myocardial perfusion imaging and exercise echocardiography: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 227–237, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nabi F, Malaty A, Shah DJ. Stress cardiac magnetic resonance. Curr Opin Cardiol 26: 385–391, 2011. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283490373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagaraj HM, Pednekar A, Corros C, Gupta H, Lloyd SG. Determining exercise-induced blood flow reserve in lower extremities using phase contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 27: 1096–1102, 2008. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oosterhof T, Tulevski II, Roest AA, Steendijk P, Vliegen HW, van der Wall EE, de Roos A, Tijssen JG, Mulder BJ. Disparity between dobutamine stress and physical exercise magnetic resonance imaging in patients with an intra-atrial correction for transposition of the great arteries. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 7: 383–389, 2005. doi: 10.1081/JCMR-200053454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pellikka PA, Nagueh SF, Elhendy AA, Kuehl CA, Sawada SG; American Society of Echocardiography . American Society of Echocardiography recommendations for performance, interpretation, and application of stress echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 20: 1021–1041, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pesenti-Rossi D, Peyrou J, Baron N, Allouch P, Aubert S, Boueri Z, Livarek B. Cardiac MRI: technology, clinical applications, and future directions [in French]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 62: 326–341, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ancard.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pflugi S, Roujol S, Akçakaya M, Kawaji K, Foppa M, Heydari B, Goddu B, Kissinger K, Berg S, Manning WJ, Kozerke S, Nezafat R. Accelerated cardiac MR stress perfusion with radial sampling after physical exercise with an MR-compatible supine bicycle ergometer. Magn Reson Med 74: 384–395, 2015. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picano E, Pibarot P, Lancellotti P, Monin JLMDP, Bonow ROMD. The emerging role of exercise testing and stress echocardiography in valvular heart disease J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 2251–2260, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinto TE, Gusso S, Hofman PL, Derraik JGB, Hornung TS, Cutfield WS, Baldi JC. Systolic and diastolic abnormalities reduce the cardiac response to exercise in adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 37: 1439–1446, 2014. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raman SV, Dickerson JA, Jekic M, Foster EL, Pennell ML, McCarthy B, Simonetti OP. Real-time cine and myocardial perfusion with treadmill exercise stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients referred for stress SPECT. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 12: 41, 2010. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raman SV, Dickerson JA, Mazur W, Wong TC, Schelbert EB, Min JK, Scandling D, Bartone C, Craft JT, Thavendiranathan P, Mazzaferri EL, Arnold JW, Gilkeson R, and Simonetti OP. Diagnostic performance of treadmill exercise cardiac magnetic resonance: the prospective, multicenter Exercise CMR’s Accuracy for Cardiovascular Stress Testing (EXACT) trial. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e003811, 2016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rayoo R, Kearney L, Grewal J, Ord M, Lu K, Smith G, Srivastava P. Cardiac MRI: indications and clinical utility—a single centre experience. Heart Lung Circ 21: S191, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.05.474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roest AA, Helbing WA, Kunz P, van den Aardweg JG, Lamb HJ, Vliegen HW, van der Wall EE, de Roos A. Exercise MR imaging in the assessment of pulmonary regurgitation and biventricular function in patients after tetralogy of fallot repair. Radiology 223: 204–211, 2002. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2231010924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roest AA, Kunz P, Lamb HJ, Helbing WA, van der Wall EE, de Roos A. Biventricular response to supine physical exercise in young adults assessed with ultrafast magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol 87: 601–605, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roest AAW, Lamb HJ, van der Wall EE, Vliegen HW, van den Aardweg JG, Kunz P, de Roos A, Helbing WA. Cardiovascular response to physical exercise in adult patients after atrial correction for transposition of the great arteries assessed with magnetic resonance imaging. Heart 90: 678–684, 2004. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.023499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sampath S, Derbyshire JA, Ledesma-Carbayo MJ, McVeigh ER. Imaging left ventricular tissue mechanics and hemodynamics during supine bicycle exercise using a combined tagging and phase-contrast MRI pulse sequence. Magn Reson Med 65: 51–59, 2011. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schnell F, Claessen G, La Gerche A, Claus P, Bogaert J, Delcroix M, Carré F, Heidbuchel H. Atrial volume and function during exercise in health and disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 19: 104, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0416-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shah R, Heydari B, Coelho-Filho O, Murthy VL, Abbasi S, Feng JH, Pencina M, Neilan TG, Meadows JL, Francis S, Blankstein R, Steigner M, di Carli M, Jerosch-Herold M, Kwong RY. Stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging provides effective cardiac risk reclassification in patients with known or suspected stable coronary artery disease. Circulation 128: 605–614, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shephard RJ. Maximal oxygen intake and independence in old age. Br J Sports Med 43: 342–346, 2009. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sicari R, Nihoyannopoulos P, Evangelista A, Kasprzak J, Lancellotti P, Poldermans D, Voigt J-U, Zamorano JL. European Association of Echocardiography, and on behalf of the European Association of E . Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement–executive summary: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur Heart J 30: 278–289, 2009. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steding-Ehrenborg K, Jablonowski R, Arvidsson PM, Carlsson M, Saltin B, Arheden H. Moderate intensity supine exercise causes decreased cardiac volumes and increased outer volume variations: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 15: 96, 2013. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sukpraphrute B, Drafts BC, Rerkpattanapipat P, Morgan TM, Kirkman PM, Ntim WO, Hamilton CA, Cockrum RL, Hundley WG. Prognostic utility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance upright maximal treadmill exercise testing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 17: 103, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0208-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tenforde AS, Cheng CP, Suh GY, Herfkens RJ, Dalman RL, Taylor CA. Quantifying in vivo hemodynamic response to exercise in patients with intermittent claudication and abdominal aortic aneurysms using cine phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 31: 425–429, 2010. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thavendiranathan P, Dickerson JA, Scandling D, Balasubramanian V, Pennell ML, Hinton A, Raman SV, Simonetti OP. Comparison of treadmill exercise stress cardiac MRI to stress echocardiography in healthy volunteers for adequacy of left ventricular endocardial wall visualization: a pilot study. J Magn Reson Imaging 39: 1146–1152, 2014. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vick GW., III The gold standard for noninvasive imaging in coronary heart disease: magnetic resonance imaging. Curr Opin Cardiol 24: 567–579, 2009. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283315553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voilliot D, Lancellotti P. Exercise testing and stress imaging in mitral valve disease. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 19: 17, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11936-017-0516-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weber TF, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Kopp-Schneider A, Ley-Zaporozhan J, Kauczor HU, Ley S. High-resolution phase-contrast MRI of aortic and pulmonary blood flow during rest and physical exercise using a MRI compatible bicycle ergometer. Eur J Radiol 80: 103–108, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zellweger MJ, Fahrni G, Ritter M, Jeger RV, Wild D, Buser P, Kaiser C, Osswald S, Pfisterer ME; Basel Stent Kosteneffektivitäts Trial (BASKET) Investigators . Prognostic value of “routine” cardiac stress imaging 5 years after percutaneous coronary intervention: the prospective long-term observational BASKET (Basel Stent Kosteneffektivitäts Trial) LATE IMAGING study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 7: 615–621, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.01.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]