Abstract

Reducing body weight has been shown to lower blood pressure in obesity-related hypertension. However, success of those lifestyle interventions is limited due to poor long-term compliance. Emerging evidence indicates that feeding schedule plays a role on the regulation of blood pressure. With two studies, we examined the role of feeding schedule on energy homeostasis and blood pressure. In study 1, rats were fed a high-fat diet (HFD) ad libitum for 24 h (Control) or for 12 h during the dark phase (time-restricted feeding, TRF). In study 2, rats fed a HFD were administered a long-acting α-MSH analog at either light onset [melanotan II (MTII) light] or dark onset (MTII dark) or saline (Control). MTII light animals ate most of their calories during the active phase, similar to the TRF group. In study 1, Control and TRF rats consumed the same amount of food and gained the same amount of weight and fat mass. Interestingly, systolic and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was lower in the TRF group. In study 2, food intake was significantly lower in both MTII groups relative to Control. Although timing of injection affected light versus dark phase food consumption, neither body weight nor fat mass differed between MTII groups. Consistent with study 1, rats consuming their calories during the active phase displayed lower MAP. These data indicate that limiting feeding to the active phase reduces blood pressure without the necessity of reducing calories or fat mass, which could be relevant to obesity-related hypertension.

Keywords: body weight, blood pressure, energy homeostasis, feeding schedule, melanotan II

INTRODUCTION

The importance of eating patterns on human health is gaining attention. Growing evidence indicates that timing of food intake impacts energy balance and cardiovascular health. Those concepts are supported by studies indicating that night-time eating syndrome is positively associated with body mass index, metabolic syndrome (8), and sleep-time nondipping blood pressure and nocturnal hypertension (38). Because it often results in irregular eating patterns, shift work has also been linked to increased risk of obesity, cardiometabolic disorders, and hypertension (5, 41). The importance of feeding schedule on body weight was reinforced by rodent studies in which restricting food availability during the inactive period amplified diet-induced obesity (DIO) (3) and disrupted body physiology (35). On the other hand, feeding paradigms that restricted energy intake to the active period, commonly termed time-restricted feeding (TRF), can prevent or reverse DIO without the necessity of reducing daily caloric intake (7). Eating during the active phase has also been shown to attenuate decline in heart function during aging (16) and to play a role on diurnal regulation of blood pressure (24, 31).

Metabolic processes and blood pressure are regulated by the circadian rhythm, which serves to coordinate physiological functions and behaviors with daily environmental fluctuations (11, 26). In most species, circadian oscillation cycles occur every 24 h when receiving normal environmental cues, predominantly light and darkness. Because glucose tolerance, insulin secretion, and diet-induced thermogenesis are all reported to be lower at night relative to morning, eating at night (inactive phase) increases health risks (32). On the other hand, blood pressure peaks in the morning and then decreases throughout the remainder of the day (30). The circadian rhythm can be entrained by feeding schedule and is affected by dietary content (25). It has been shown that high-fat diets disrupt normal feeding patterns and desynchronize the circadian rhythm (25).

Natural feeding patterns are orchestrated by signals that either favor or inhibit energy intake. The central melanocortin system is an important candidate for the circadian control of food intake. In the brain, melanotropic activity requires the anorexigenic peptide α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) to bind to the MC3 receptor and the MC4 receptor. In rats, hypothalamic α-MSH levels peak within the first 2 h of light phase (33). Because of the rapid degradation of α-MSH in vivo (~20 min), synthetic melanotropic peptides resistant to enzymatic degradation have been generated (42), including melanotan II (MTII), a highly potent α-MSH analog. Preliminary data from our laboratory showed that MTII may be a pharmacological modulator of feeding schedule. Besides its effects on feeding and energy store homeostasis, the melanocortin system regulates blood pressure through the control of the sympathetic nervous system outflow. When administered centrally, α-MSH significantly increases blood pressure (21). Although the regulation of blood pressure by the central melanocortin system is well described, the hemodynamic actions of systemically administered melanotropic peptides remain poorly documented.

TRF has been shown to improve body composition in both humans (17) and rodents (7). While TRF does not affect the overall caloric consumption in mice, most humans participating in TRF naturally reduce their caloric intake (17). Therefore, it is uncertain whether the antiobesity effect of TRF is simply a reflection of caloric reduction. Since the effect of feeding schedule has been primarily studied in mice and fruit flies, we aimed to further document the effects of TRF in other model organisms by conducting studies evaluating the roles of light-phase (inactive) versus dark-phase (active) food consumption on body weight and composition in rats. Furthermore, we aimed to further characterize the roles of feeding schedule on cardiovascular functions, currently limited to a few models such as Drosophila and dog (29, 31). We compared Control versus TRF animals fed a high-fat diet. We hypothesized that TRF would prevent or reduce obesity and lower blood pressure. We also used MTII as a pharmacological modulator of feeding in rats. We compared animals treated at either light onset or dark onset. We anticipated both MTII groups to lose body weight, but we predicted a disruption of normal light phase versus dark phase food consumption in animals treated at dark onset. Hence, we hypothesized a more pronounced MTII-mediated weight loss and beneficial effects on blood pressure in animals receiving the injections at light onset.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Six-month-old male Fisher 344 × Brown Norway (F344BN) rats (n = 24) were obtained from the National Institute on Aging Colony at Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The number of animals per group was determined by an a priori power calculation that was based on published blood pressure data in rats treated with MTII (27). We determined that a sample size of six animals per group was sufficient to achieve 80% power with 5% α-level. Adult F344BN rats were selected because they display relatively stable body weight under ad libitum access to food (1). Upon arrival, animals were housed under standard conditions, individually with corn cob bedding on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on at 7 AM). Rats were initially fed a standard rodent chow (18% kcal from fat, no sucrose, 3.1 kcal/g, diet 2018; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and remained on this diet for 7 days to assess baseline light-phase versus dark-phase food consumption. At day 7, all animals were then switched to a novel high-fat diet (60% kcal from fat, 20% protein, 20% carbohydrate, including 6.8% sucrose; 5.24 kcal/g, diet 12492; Research Diet, Brunswick, NJ) for the remainder of the experiment. The objective of this study was to examine the consequences of an obesogenic diet without and with scheduled feeding on obesity and hypertension with a pre (standard diet) and post (obesogenic diet) design; thus, the standard diet was used only before the introduction of the obesogenic diet. In addition to HF content, several components of the obesogenic diet, such as sugar, cholesterol, and phytoestrogens may have also contributed to observed results (39). A transient hyperphagia occurs when rats are introduced a novel high-fat diet (22). Because the role of the melanocortin system in this process is unknown, all rats were allowed a second acclimation period until their daily caloric intake was normalized to the baseline chow diet value.

There is disparity in initial body weight since the National Institute on Aging is the only vendor breeding F344BN, and rats can only be ordered by age, not by weight. Also, response to a high-fat diet is highly variable. Therefore, at day 17, rats were assigned to experimental groups based on body weight to ensure similar baseline value distributions across groups for longitudinal statistical comparisons. Health status, body weight, and food intake were monitored twice daily throughout the experiment. All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Florida’s Animal Care and Use Committee, and in compliance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” guidelines. We attempted to replace animals by other models, but other organisms are not appropriate to evaluate the physiological effect of scheduled feeding or MTII. We refined our techniques and employed a nonsurgical approach to reduce pain in animals. This is a widely used method to measure blood pressure instead of telemetry devices that must be implanted under anesthesia. We also aimed at reducing the number of animals, by conducting an experiment that would use two separate approaches using a single control group. Because the same animals were used as controls for both experiments, all data sets were statistically analyzed together. However, for clarity, data are presented separately as study 1 and study 2.

Study 1. effects of TRF on energy homeostasis and blood pressure.

Animals had unlimited access to food during the 12-h dark phase (time-restricted feeding, TRF; n = 6) or 24 h per day (Control; n = 6). Because the same Control animals served in both studies, all animals in TRF and Control groups received two daily vehicle injections to match stress induced by handling, as described below.

Study 2: effects of MTII delivery at light onset versus dark onset on energy homeostasis and blood pressure.

Animals had ad libitum access to food and were separated into three groups: 1) Control, 2) MTII light, and 3) MTII dark (n = 6/group). Rats were injected twice daily for 21 days, except during the acclimation period. The animals in the Control group were injected with sterile 0.9% saline (1 ml/kg ip) twice daily, at light onset (7 AM), and at dark onset (7 PM). Rats belonging to the MTII light group received daily injections of MTII (3 mg/kg; 1 ml/kg ip; Genscript, Piscataway Township, NJ) at light onset and 0.9% saline at dark onset. The MTII dark group was administered 0.9% saline at light onset and MTII (3 mg/kg; 1 ml/kg ip; Genscript) at dark onset every day. This dosage was determined by a dose-response study (unpublished data) in which a daily dose of 3 mg/kg induced a higher body weight loss and hypophagia than a daily dose of 2 mg/kg. However, there was no additional physiological response beyond the dose selected for the present study. Doses selected in our dose-response study were based on published literature (6).

Determination of body composition using time-domain nuclear magnetic resonance.

Body composition was assessed using time domain-NMR; Minispec, Bruker Optics, The Woodlands, TX). The MiniSpec quantifies three main components of body composition (fat, free body fluid, and lean body mass) by acquiring signals from protons in the sample area. Scans were acquired by placing conscious rats into a cylindrical restrainer that was inserted into the analyzer. The average of two scans for each animal was used as the final value.

Measurement of blood pressure.

Blood pressure was measured between 12 PM and 3 PM at days 16 and 41 from arrival by a noninvasive tail cuff system (CODA, Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). To acclimate to the restraining device, animals were trained three times on separate days, and they were placed in a restraining device similar to that used for blood pressure measurements. Animals remained in the training restraining device for 1, 5, and 10 min. On the days of actual measurements, each animal was allowed an acclimation period of 10 min in the restraining device. The mean of three inflation/deflation cycles were used as the final values. Thereafter, systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was recorded by the computer system using the CODA software (Kent Scientific). Given that no blood pressure data in rats under similar feeding paradigm were available, we used tail cuff system over the alternative surgical approach (radiotelemetry). A nonsurgical technique minimized pain in animals and prevented the need of anesthesia and analgesics that would have influenced our data, especially feeding behaviors recorded before treatments.

Tissue collection, harvesting, and preparation.

All rats were euthanized between 10 AM and 12 PM by thoracotomy and exsanguination under anesthesia (isoflurane; 5%). Several organs and tissues were removed and weighed (Mettler AE 163): liver, fat depots (mesenteric, perirenal, epididymal, and retroperitoneal), and muscles (tibialis anterior, lateral gastrocnemius, plantaris, and soleus).

Statistical analyses.

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (9). Data sets for study 1 and study 2 were analyzed simultaneously through one-way ANOVA with repeated measures (longitudinal analyses), or regular one-way ANOVA was used to compare mean between groups for single time point analyses. Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests were applied only in case of a significant event. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Timing of MTII injection alters feeding pattern without affecting the overall daily caloric consumption.

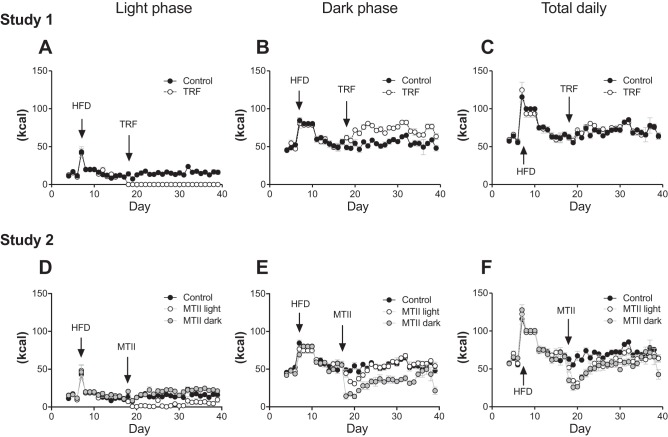

Consistent with previous studies, switching from chow to a novel high-fat diet induced a transient hyperphagia in all rats (22, 23). In study 1, the TRF paradigm was initiated when energy intake returned to that consumed on the chow diet. Control rats consumed more calories during light phase (Fig. 1A; Control vs. TRF: P < 0.001) and fewer during dark phase compared with TRF rats (Fig. 1B; Control vs. TRF: P < 0.001). However, total daily feeding was similar between the two groups. In study 2, MTII treatment began when caloric intake returned to the same level consumed on the chow diet. Timing of MTII treatment significantly affected light versus dark-phase food consumption. Light-phase feeding was highest in the MTII dark group and lowest in the MTII light group (Fig. 1D: Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.01; MTII light vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001). Dark-phase feeding was not changed in MTII light animals but was significantly lower in MTII dark animals (Fig. 1E: Control vs. MTII light: not significant (NS); Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001). Both MTII groups exhibited chronic hypophagia; however, despite significant differences in light versus dark-phase food consumption, daily caloric consumption was similar between MTII light and MTII dark groups (Fig. 1F: Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS.).

Fig. 1.

Light phase vs. dark phase food consumption. Food intake was recorded twice daily: at light onset and dark onset throughout the studies. Study 1. A: light-phase feeding. Control vs. time-restricted feeding (TRF): P < 0.001. B: dark-phase feeding. Control vs. TRF: P < 0.001. C: total daily feeding. Control vs. TRF: nonsignificant (NS). Study 2. D: light-phase feeding. Control vs. melanotan II (MTII) light: P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.01; MTII light vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001. E: dark phase feeding. Control vs. MTII light: NS; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001. D: total daily feeding. Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001, MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS.

Feeding schedule does not appear to play a role in body weight and body composition regulation in adult rats.

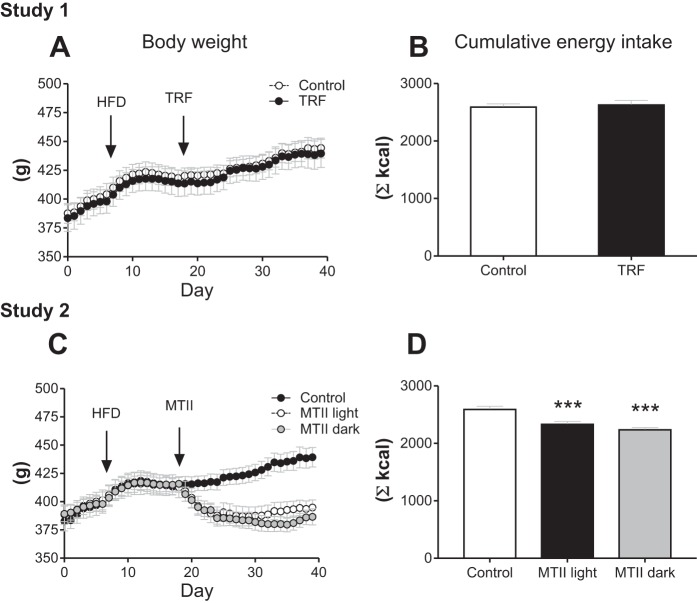

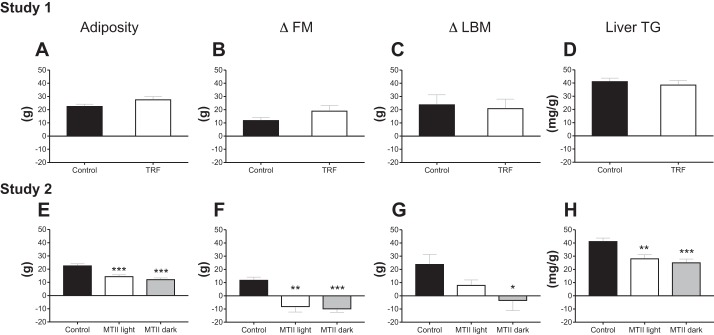

Rats were assigned to groups based on their body weight at day 18; initial body weights were statistically similar across groups in study 1 (Control: 382.7 ± 8.6; TRF: 383.5 ± 11.5) and in study 2 (Control: 382.7 ± 8.6 g; MTII Light 388.2 ± 8.7 g; MTII dark: 389.2 ± 6.8 g). In study 1, in contrast to previous findings in mice (12, 19), TRF did not prevent or reduce the progression of diet-induced obesity in rats (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, consistent with mouse models (7), there was no effect of TRF on cumulative food intake from arrival (Fig. 2B) or from beginning of treatment (data not shown). In study 2, both MTII groups lost a significant amount of body weight; however, timing of injection did not affect the extent of body weight loss (Fig. 2C: Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS). Cumulative energy intake was lower in both MTII groups compared with Control but was not different between the MTII groups (Fig. 2D: Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS). In study 1, there was no effect of TRF on intra-abdominal adiposity, individual fat pads, muscle mass, changes in fat mass, changes in lean body mass, or liver TG content (Table 1; Fig. 3, A–D). In study 2, both MTII groups displayed significantly lower abdominal fat mass and significant loss in fat mass throughout the study, but timing of MTII injection did not affect those responses (Fig. 3, E and F; Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.01; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS). However, while all four abdominal fat pads were significantly smaller in the MTII dark group, we found that there was no significant difference in pWAT mass between MTII light group and the Control group, suggesting a slightly higher response in the MTII dark group (Table 1). Changes in lean body mass were significantly altered in the MTII dark group but not in the MTII light group compared with Control (Fig. 3G; Control vs. MTII light: NS; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.05; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS). Following the same pattern, liver was significantly smaller in animals that received MTII light injections but not in those that received MTII dark injections compared with Control-treated animals (Table 1: Control vs. MTII light: NS; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.05; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS). Liver TG content was lower in both MTII groups compared with the Control group, but there was no difference between the MTII light and the MTII dark groups (Fig. 3H: Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.01; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS).

Fig. 2.

Body weight and cumulative food intake. Body weight was recorded twice daily: at light onset and dark onset throughout the studies. Cumulative food intake represents the total amount of food consumed throughout the studies. Study 1. A: body weight. Control vs. time-restricted feeding (TRF): not significant (NS). B: cumulative food intake. Control vs. TRF: NS. Study 2. C: body weight. Control vs. melanotan II (MTII) light: P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS. D: Cumulative food intake. Control vs. MTII light: ***P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: ***P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS.

Table 1.

Lean and fat tissue weights and baseline blood pressure

| Control | TRF | |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | ||

| Gastrocnemius lateral, g | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 0.92 ± 0.01 |

| Tibialis anterior, g | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.03 |

| Plantaris, g | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.01 |

| Soleus, g | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 |

| rtWAT, g | 6.52 ± 0.34 | 7.64 ± 0.89 |

| pWAT, g | 2.33 ± 0.30 | 3.23 ± 0.25 |

| eWAT, g | 8.84 ± 0.69 | 10.29 ± 1.03 |

| mWAT, g | 5.10 ± 0.36 | 6.65 ± 0.59 |

| Liver, g | 8.87 ± 0.42 | 9.17 ± 0.53 |

| Baseline MAP, mmHg | 82.2 ± 3.9 | 86.2 ± 6.8 |

| Baseline SAP, mmHg | 105.8 ± 3.7 | 114.7 ± 9.4 |

| Baseline DAP, mmHg | 71.2 ± 4 | 77.2 ± 7.5 |

| Control | MTII light | MTII dark | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 2 | |||

| Gastrocnemius lateral, g | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.03 |

| Tibialis anterior, g | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.02 |

| Plantaris, g | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.02 |

| Soleus, g | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.00 | 0.16 ± 0.00 |

| rtWAT, g | 6.52 ± 0.34 | 3.68 ± 0.31*** | 2.75 ± 0.38*** |

| pWAT, g | 2.33 ± 0.30 | 1.71 ± 0.19 | 1.34 ± 0.26* |

| eWAT, g | 8.84 ± 0.69 | 5.81 ± 0.34** | 5.34 ± 0.30*** |

| mWAT, g | 5.10 ± 0.36 | 3.49 ± 0.29** | 2.98 ± 0.28*** |

| Liver, g | 8.87 ± 0.42 | 7.65 ± 0.37 | 7.18 ± 0.38* |

| Baseline MAP, mmHg | 82.2 ± 3.9 | 92.6 ± 10.2 | 84.3 ± 7.6 |

| Baseline SAP, mmHg | 105.8 ± 3.7 | 113.2 ± 8.8 | 106.2 ± 8.7 |

| Baseline DAP, mmHg | 71.2 ± 4 | 83 ± 11 | 74.1 ± 7.1 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. DAP, diastolic arterial pressure; eWAT, epidydimal white adipose tissue; MAP, mean arterial pressure; mWAT, mesenteric white adipose tissue; pWAT, perirenal white adipose tissue; rtWAT, retroperitoneal white adipose tissue; SAP, systolic arterial pressure.

P < 0.05, significantly different from Control.

P < 0.01, significantly different from Control.

P < 0.001, significantly different from Control.

Fig. 3.

Body composition. Study 1. A: adiposity. Represents the sum of abdominal fat pads also reported in Table 1. Control vs. time-restricted feeding (TRF): not significant (NS). B: changes in fat mass (delta fat mass; ΔFM) were assessed by time-domain nuclear magnetic resonance (TD-NMR) and calculated by subtracting absolute fat mass recorded at day 16 (two days before TRF or melanotan II (MTII) started) from absolute fat mass recorded at day 39 (end point). Control vs. TRF: NS. C: changes in lean body mass (delta lean body mass; ΔLBM) were assessed by TD-NMR, and values were obtained by subtracting absolute lean body mass recorded at day 16 (two days before TRF or MTII started) from absolute LBM recorded at day 39 (end point). Control vs. TRF: NS. D: liver TG. Control vs. TRF: NS. Study 2. E: adiposity. Control vs. MTII light: ***P < 0.001; Control vs. MTII dark: ***P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS. F: ΔFM. Control vs. MTII light: **P < 0.01; Control vs. MTII dark: ***P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS. G: ΔLBM. Control vs. MTII light: NS, Control vs. MTII dark: *P < 0.05, MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS. H: liver TG. Control vs. MTII light: **P < 0.01; Control vs. MTII dark: ***P < 0.001; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS.

Feeding during the active phase reduces blood pressure in adult rats.

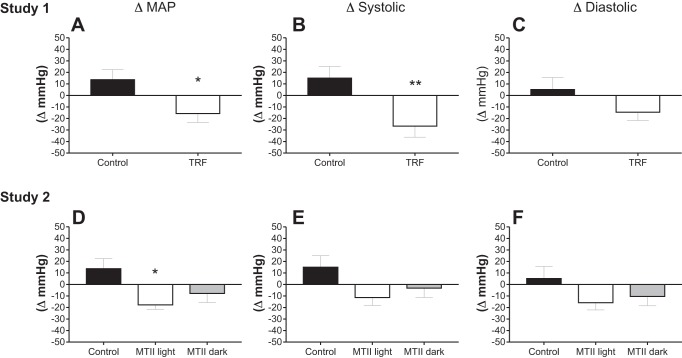

There were no statistical differences in baseline blood pressure values (Table 1). In the Control group, MAP, and systolic pressure increased by ~15 mmHg from day 16 to 41. However, despite the lack of an antiobesity effect, TRF decreased MAP by 15 mmHg and systolic blood pressure by 27 mmHg (systolic) within the same time frame (Fig. 4, A and B: Control vs. TRF: P < 0.05 for ΔMAP and P < 0.01 for Δsystolic). There was no effect of TRF on changes in diastolic pressure (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, in study 2, we found limited effects of MTII on blood pressure. We detected a significant difference in ΔMAP in MTII light rats relative to control rats (Fig. 4D: Control vs. MTII light: P < 0.05; Control vs. MTII dark: NS; MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS), but there was no effect of MTII on Δsystolic and Δdiastolic blood pressure (Fig. 4, E and F).

Fig. 4.

Changes in blood pressure. Changes in blood pressure were obtained by subtracting absolute blood pressure recorded 4 days before time-restricted feeding (TRF) or melanotan II (MTII) treatment, at day 14 from that recorded at end point. Study 1. A: delta mean arterial pressure (ΔMAP) Control vs. TRF: *P < 0.05. B: delta systolic (Δsystolic). Control vs. TRF: **P < 0.01. C: delta diastolic (Δdiastolic). Control vs. TRF: nonsignificant (NS). Study 2. D: ΔMAP. Control vs. MTII light: *P < 0.05, Control vs. MTII dark: NS, MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS. E: Δsystolic. Control vs. MTII light: NS. Control vs. MTII dark: NS. MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS. F: Δdiastolic. Control vs. MTII light: NS. Control vs. MTII dark: NS. MTII light vs. MTII dark: NS.

DISCUSSION

Obesity has become a major health concern currently reaching global pandemic proportions (13). The association between obesity and hypertension is well recognized in the literature (10). In the United States, ~30% of the population is obese (15) and/or hypertensive (18). Notably, more than 65% of new cases of hypertension are diagnosed in overweight or obese people (14). Given the associated cardiometabolic diseases and the economic burden of obesity, new therapeutic approaches for weight loss and/or hypertension are needed. Lifestyle interventions such as caloric restriction and increased physical activity have been the first-line therapy to combat obesity and its cardiovascular complications due to ease of access and low cost. However, success of those behavioral modifications has proven to be limited due to poor long-term compliance (2). There is an emerging theory claiming that not only caloric intake but also temporal spreading of energy intake contributes to the regulation of energy homeostasis (40). Thus, TRF has been proposed as an alternative behavioral intervention because it deemphasizes the importance of caloric restriction.

Although in agreement with earlier findings showing that TRF can prevent and treat cardiovascular disorders, our studies provide an extension of the current knowledge. A novel finding is that limiting feeding to the active phase reduced systolic arterial blood pressure by 27 mmHg without the necessity of caloric reduction or fat mass loss. Our discovery is highly relevant to humanity considering that lowering systolic blood pressure by 30 mmHg in humans reduces incidence of stroke by 72%, and that hypertension is the most important contributor to mortality (28). Further studies will be needed to determine whether limiting the feeding window has the ability to lower blood pressure to the same extent as it does in rats and if those effects are sufficient to replace existing pharmacological treatment.

Given that most people treated with antihypertensive drugs experience negative side effects, alternative nonpharmacological approaches may be an attractive therapeutic strategy to combat hypertension. In study 1, we found that limiting feeding to a 12-h window reduced MAP and systolic blood pressure without reducing body weight, fat mass, hepatic TG, or food intake. Our data are consistent with another previous report showing that TRF in adult rats (6 mo old; same age as the rats in the present study) did not inhibit HFD-induced weight gain (34). However, the results from the present study are not consistent with mouse models presented by Chaix et al. (7) in which the same intervention (TRF of 12 h during active phase) protected against HFD-induced obesity. Our study shows that the antiobesity effect of TRF may not occur in all species or that the feeding window may need further restriction in rats, possibly due to anatomical divergences (i.e., gall bladder is present in mice and absent in rats) that may influence dietary lipid processing and storage under TRF. To date, there are only a limited number of published TRF studies conducted in rats. HFD-fed juvenile rats (5 wk old) placed on TRF (9 h during active phase) on weekdays gained significantly less weight over the course of a 12-wk study compared with Control-fed animals (34). However, there were considerable variations in experimental design, such as rat strain, duration of feeding window, and age that could have contributed to the discrepancy between this and the present study. The only other study showing that TRF does not work in adult rats did not include a valid control group, making the interpretation that adult rats do not respond to TRF speculative. Another observation in our model is that expected hyperphagia after switching from a chow to a high-fat diet occurred only in the dark and not in the light phase. We found a mild but not significant reduction of the percentage of caloric intake consumed during the light phase when rats were fed the HFD compared with the chow diet (20.6 ± 0.6% vs. 22.3 ± 0.9%; data not shown). In juvenile rats, switching from a chow to a high-fat diet significantly increased feeding during the light phase but not during the dark phase (34). It is possible that changes in eating behaviors in response to a high-fat diet depend on age. The absence of an antiobesity effect of TRF in our model may also be explained by differential changes in eating behaviors in response to a high-fat diet across species. In mice, the daily rhythm of eating is markedly disrupted during chronic high-fat feeding (4). The rhythm of feeding is severely compromised or absent in high-fat-fed mice, such that eating pattern is almost evenly distributed across an entire 24-h day (4). In our model, light-phase versus dark-phase food consumption was highly preserved, and there was only a slight difference in light-phase feeding between the Control and TRF groups, which could explain why TRF did not decrease body weight to the same extent. The present study is limited by the fact that we did not include a control diet. Therefore, it is not possible to fully distinguish the effects of MTII that were due to HFD. However, because caloric intake was rapidly normalized to initial chow diet level, it suggests that rats would have responded similarly to TRF under a control chow diet, although this hypothesis needs to be confirmed. On the other hand, the results of study 2 might have been more significantly driven by the HFD. Pierroz et al. (36) reported a more prolonged hypophagic response to MTII in mice fed a HFD than in those fed a low-fat diet. Considering that HFD has been shown to increase blood pressure in rodents, it is possible that changes in arterial blood pressure by MTII were more pronounced due to higher basal level on a high-fat diet. Repeating the experiments with a control low-fat diet may help better discriminate the cardiovascular effects that are strictly due to MTII-timed therapy from those driven by the HFD.

Timing of MTII delivery significantly affected light-phase versus dark-phase food consumption in HFD-fed rats. Peripheral injections of MTII at the beginning of the light phase chronically reduced feeding until the dark phase, and vice versa. Light-phase versus dark-phase food consumption in the MTII light group resembled those of the TRF group. Similar to TRF rats, MTII light animals displayed a significant reduction of MAP. However, delta systolic and diastolic pressures were unchanged by the MTII treatments. This could be due to large individual variability and the lack of statistical power. In the MTII dark group, although the P value is not significant, the effect direction of MAP is consistent with that observed in the MTII light group. Further experiments would help determine whether a significant difference between Control versus MTII dark could be detected.

In the present study, MTII Light and MTII Dark Groups consumed the same amount of food and lost the same amount of weight. Because the effects of MTII light on blood pressure are consistent with those observed in TRF group, we conclude that limiting food consumption to the active phase may have beneficial cardiovascular effects. Reproducing these experiments, using the same techniques as well as other more comprehensive approaches (i.e., telemetry), would help build stronger overall evidence of a role of feeding schedule on blood pressure.

Perspectives and Significance

Our studies indicate that restricting caloric intake to the active period may be a potential intervention to reduce blood pressure. Because overweight and obesity are associated with other health complications, losing weight should remain a major focus. However, caloric restriction in the treatment of obesity can be difficult to achieve in the long term (20) and can lead to eating pathologies (37). Therefore, focusing on feeding schedule and timed MTII therapy may constitute effective therapeutic strategies to obtain some clinical benefits such as blood pressure reduction, even in the absence of weight loss. Future studies should aim to determine whether reducing blood pressure via TRF would be even more pronounced when weight loss achieved.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (DK-091710).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I.C., H.Z.T., D.M., C.S.C., N.T., and P.J.S. conceived and designed research; I.C., H.Z.T., and S.M.G. performed experiments; I.C., H.Z.T., D.M., C.S.C., and P.J.S. analyzed data; I.C., H.Z.T., D.M., C.S.C., N.T., and P.J.S. interpreted results of experiments; I.C. prepared figures; I.C. drafted manuscript; I.C., H.Z.T., D.M., C.S.C., and P.J.S. edited and revised manuscript; I.C., H.Z.T., S.M.G., D.M., C.S.C., N.T., and P.J.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altun M, Bergman E, Edström E, Johnson H, Ulfhake B. Behavioral impairments of the aging rat. Physiol Behav 92: 911–923, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr 74: 579–584, 2001. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arble DM, Bass J, Laposky AD, Vitaterna MH, Turek FW. Circadian timing of food intake contributes to weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17: 2100–2102, 2009. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branecky KL, Niswender KD, Pendergast JS. Disruption of daily rhythms by high-fat diet is reversible. PLoS One 10: e0137970, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brum MC, Filho FF, Schnorr CC, Bottega GB, Rodrigues TC. Shift work and its association with metabolic disorders. Diabetol Metab Syndr 7: 45, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13098-015-0041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cettour-Rose P, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F. The leptin-like effects of 3-d peripheral administration of a melanocortin agonist are more marked in genetically obese Zucker (fa/fa) than in lean rats. Endocrinology 143: 2277–2283, 2002. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaix A, Zarrinpar A, Miu P, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab 20: 991–1005, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Night eating syndrome and nocturnal snacking: association with obesity, binge eating and psychological distress. Int J Obes 31: 1722–1730, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA, Gilchrist A, Hoyer D, Insel PA, Izzo AA, Lawrence AJ, MacEwan DJ, Moon LD, Wonnacott S, Weston AH, McGrath JC. Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471, 2015. doi: 10.1111/bph.12856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davy KP, Hall JE. Obesity and hypertension: two epidemics or one? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R803–R813, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00707.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dibner C, Schibler U. Circadian timing of metabolism in animal models and humans. J Intern Med 277: 513–527, 2015. doi: 10.1111/joim.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan MJ, Smith JT, Narbaiza J, Mueez F, Bustle LB, Qureshi S, Fieseler C, Legan SJ. Restricting feeding to the active phase in middle-aged mice attenuates adverse metabolic effects of a high-fat diet. Physiol Behav 167: 1–9, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, Farzadfar F, Riley LM, Ezzati M; Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index) . National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 377: 557–567, 2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrison RJ, Kannel WB, Stokes J III, Castelli WP. Incidence and precursors of hypertension in young adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Prev Med 16: 235–251, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gartner DR, Taber DR, Hirsch JA, Robinson WR. The spatial distribution of gender differences in obesity prevalence differs from overall obesity prevalence among US adults. Ann Epidemiol 26: 293–298, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill S, Le HD, Melkani GC, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding attenuates age-related cardiac decline in Drosophila. Science 347: 1265–1269, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1256682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill S, Panda S. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cell Metab 22: 789–798, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA 290: 199–206, 2003. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, DiTacchio L, Bushong EA, Gill S, Leblanc M, Chaix A, Joens M, Fitzpatrick JA, Ellisman MH, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab 15: 848–860, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heymsfield SB, Harp JB, Reitman ML, Beetsch JW, Schoeller DA, Erondu N, Pietrobelli A. Why do obese patients not lose more weight when treated with low-calorie diets? A mechanistic perspective. Am J Clin Nutr 85: 346–354, 2007. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill C, Dunbar JC. The effects of acute and chronic alpha melanocyte stimulating hormone (αMSH) on cardiovascular dynamics in conscious rats. Peptides 23: 1625–1630, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(02)00103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judge MK, Zhang J, Tümer N, Carter C, Daniels MJ, Scarpace PJ. Prolonged hyperphagia with high-fat feeding contributes to exacerbated weight gain in rats with adult-onset obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R773–R780, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00727.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judge MK, Zhang Y, Scarpace PJ. Responses to the cannabinoid receptor-1 antagonist, AM251, are more robust with age and with high-fat feeding. J Endocrinol 203: 281–290, 2009. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawano Y. Diurnal blood pressure variation and related behavioral factors. Hypertens Res 34: 281–285, 2011. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohsaka A, Laposky AD, Ramsey KM, Estrada C, Joshu C, Kobayashi Y, Turek FW, Bass J. High-fat diet disrupts behavioral and molecular circadian rhythms in mice. Cell Metab 6: 414–421, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar Jha P, Challet E, Kalsbeek A. Circadian rhythms in glucose and lipid metabolism in nocturnal and diurnal mammals. Mol Cell Endocrinol 418: 74–88, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, Cui BP, Zhang LL, Sun HJ, Liu TY, Zhu GQ. Melanocortin 3/4 receptors in paraventricular nucleus modulate sympathetic outflow and blood pressure. Exp Physiol 98: 435–443, 2013. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.067256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Bull F, Burnett RT, Byers TE, Calabria B, Carapetis J, Carnahan E, Chafe Z, Charlson F, Chen H, Chen JS, Cheng AT, Child JC, Cohen A, Colson KE, Cowie BC, Darby S, Darling S, Davis A, Degenhardt L, Dentener F, Des Jarlais DC, Devries K, Dherani M, Ding EL, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Edmond K, Ali SE, Engell RE, Erwin PJ, Fahimi S, Falder G, Farzadfar F, Ferrari A, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Fowkes FG, Freedman G, Freeman MK, Gakidou E, Ghosh S, Giovannucci E, Gmel G, Graham K, Grainger R, Grant B, Gunnell D, Gutierrez HR, Hall W, Hoek HW, Hogan A, Hosgood HD III, Hoy D, Hu H, Hubbell BJ, Hutchings SJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacklyn GL, Jasrasaria R, Jonas JB, Kan H, Kanis JA, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Khang YH, Khatibzadeh S, Khoo JP, Kok C, Laden F, Lalloo R, Lan Q, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Leigh J, Li Y, Lin JK, Lipshultz SE, London S, Lozano R, Lu Y, Mak J, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Marcenes W, March L, Marks R, Martin R, McGale P, McGrath J, Mehta S, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Micha R, Michaud C, Mishra V, Mohd Hanafiah K, Mokdad AA, Morawska L, Mozaffarian D, Murphy T, Naghavi M, Neal B, Nelson PK, Nolla JM, Norman R, Olives C, Omer SB, Orchard J, Osborne R, Ostro B, Page A, Pandey KD, Parry CD, Passmore E, Patra J, Pearce N, Pelizzari PM, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Pope D, Pope CA III, Powles J, Rao M, Razavi H, Rehfuess EA, Rehm JT, Ritz B, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, Rodriguez-Portales JA, Romieu I, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Roy A, Rushton L, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Sapkota A, Seedat S, Shi P, Shield K, Shivakoti R, Singh GM, Sleet DA, Smith E, Smith KR, Stapelberg NJ, Steenland K, Stöckl H, Stovner LJ, Straif K, Straney L, Thurston GD, Tran JH, Van Dingenen R, van Donkelaar A, Veerman JL, Vijayakumar L, Weintraub R, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams W, Wilson N, Woolf AD, Yip P, Zielinski JM, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380: 2224–2260, 2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melkani GC, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding for prevention and treatment of cardiometabolic disorders. J Physiol 595: 3691–3700, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millar-Craig MW, Bishop CN, Raftery EB. Circadian variation of blood-pressure. Lancet 311: 795–797, 1978. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mochel JP, Fink M, Bon C, Peyrou M, Bieth B, Desevaux C, Deurinck M, Giraudel JM, Danhof M. Influence of feeding schedules on the chronobiology of renin activity, urinary electrolytes and blood pressure in dogs. Chronobiol Int 31: 715–730, 2014. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2014.897711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris CJ, Purvis TE, Mistretta J, Scheer FA. Effects of the internal circadian system and circadian misalignment on glucose tolerance in chronic shift workers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101: 1066–1074, 2016. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Donohue TL, Miller RL, Pendleton RC, Jacobowitz DM. Demonstration of an endogenous circadian rhythm of α-melanocyte stimulating hormone in the rat pineal gland. Brain Res 186: 145–155, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsen MK, Choi MH, Kulseng B, Zhao CM, Chen D. Time-restricted feeding on weekdays restricts weight gain: A study using rat models of high-fat diet-induced obesity. Physiol Behav 173: 298–304, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opperhuizen AL, Wang D, Foppen E, Jansen R, Boudzovitch-Surovtseva O, de Vries J, Fliers E, Kalsbeek A. Feeding during the resting phase causes profound changes in physiology and desynchronization between liver and muscle rhythms of rats. Eur J Neurosci 44: 2795–2806, 2016. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierroz DD, Ziotopoulou M, Ungsunan L, Moschos S, Flier JS, Mantzoros CS. Effects of acute and chronic administration of the melanocortin agonist MTII in mice with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 51: 1337–1345, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaumberg K, Anderson D. Dietary restraint and weight loss as risk factors for eating pathology. Eat Behav 23: 97–103, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smolensky MH, Hermida RC, Reinberg A, Sackett-Lundeen L, Portaluppi F. Circadian disruption: New clinical perspective of disease pathology and basis for chronotherapeutic intervention. Chronobiol Int 33: 1101–1119, 2016. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2016.1184678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thigpen JE, Setchell KD, Ahlmark KB, Locklear J, Spahr T, Caviness GF, Goelz MF, Haseman JK, Newbold RR, Forsythe DB. Phytoestrogen content of purified, open- and closed-formula laboratory animal diets. Lab Anim Sci 49: 530–536, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tinsley GM, La Bounty PM. Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutr Rev 73: 661–674, 2015. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Drongelen A, Boot CR, Merkus SL, Smid T, van der Beek AJ. The effects of shift work on body weight change—a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 37: 263–275, 2011. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallingford N, Perroud B, Gao Q, Coppola A, Gyengesi E, Liu ZW, Gao XB, Diament A, Haus KA, Shariat-Madar Z, Mahdi F, Wardlaw SL, Schmaier AH, Warden CH, Diano S. Prolylcarboxypeptidase regulates food intake by inactivating α-MSH in rodents. J Clin Invest 119: 2291–2303, 2009. doi: 10.1172/JCI37209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]