Abstract

It has long been known that chronic metabolic disease is associated with a parallel increase in the risk for developing peripheral vascular disease. Although more clinically relevant, our understanding about reversing established vasculopathy is limited compared with our understanding of the mechanisms and development of impaired vascular structure/function under these conditions. Using the 13-wk-old obese Zucker rat (OZR) model of metabolic syndrome, where microvascular dysfunction is sufficiently established to contribute to impaired skeletal muscle function, we imposed a 7-wk intervention of chronic atorvastatin treatment, chronic treadmill exercise, or both. By 20 wk of age, untreated OZRs manifested a diverse vasculopathy that was a central contributor to poor muscle performance, perfusion, and impaired O2 exchange. Atorvastatin or exercise, with the combination being most effective, improved skeletal muscle vascular metabolite profiles (i.e., nitric oxide, PGI2, and thromboxane A2 bioavailability), reactivity, and perfusion distribution at both individual bifurcations and within the entire microvascular network versus responses in untreated OZRs. However, improvements to microvascular structure (i.e., wall mechanics and microvascular density) were less robust. The combination of the above improvements to vascular function with interventions resulted in an improved muscle performance and O2 transport and exchange versus untreated OZRs, especially at moderate metabolic rates (3-Hz twitch contraction). These results suggest that specific interventions can improve specific indexes of function from established vasculopathy, but either this process was incomplete after 7-wk duration or measures of vascular structure are either resistant to reversal or require better-targeted interventions.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We used atorvastatin and/or chronic exercise to reverse established microvasculopathy in skeletal muscle of rats with metabolic syndrome. With established vasculopathy, atorvastatin and exercise had moderate abilities to reverse dysfunction, and the combined application of both was more effective at restoring function. However, increased vascular wall stiffness and reduced microvessel density were more resistant to reversal.

Listen to this article’s corresponding podcast at https://ajpheart.podbean.com/e/reversal-of-microvascular-dysfunction/.

Keywords: microvascular dysfunction, peripheral vascular disease, regulation of blood flow, reversing vascular disease, rodent models of the metabolic syndrome, vascular dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

One of the major contributors to the functional or clinical manifestations of peripheral vascular disease is the progressive loss of microvessel and microvascular network structure and function, which is tightly coupled to developing metabolic disease in afflicted animals (9, 15) or humans (20, 25). This compromised function within the microcirculation can take multiple forms, including impairments to arteriolar reactivity, mechanical changes to the microvessel wall, and a progressive lowering of microvessel density (rarefaction) within the skeletal muscle (14, 26). Taken together, these impede effective mass transport and exchange and the regulation of blood flow to and perfusion within skeletal muscle (9, 23). In addition, whereas the functional impact of these impairments may be modest under resting or low metabolic demand conditions, their cumulative impact becomes more severe as muscle activity increases (6, 13, 28). Given the insidious nature of the development of peripheral vascular diseases (PVDs) and the very real clinical challenge of reversing the development of established vasculopathy in affected patients (rather than blunting its subsequent development from an otherwise “healthy” condition), investigation into whether/how a compromised microvascular network can be restored to a more normal level of structure and integrated function represents an important area of investigation. Arterial reconstructive surgery for symptomatic PVDs can restore macrovascular perfusion, but its effects on microvascular dysfunction are unclear. Persistent microvascular dysfunction after successful macrovascular reperfusion may explain why arterial reconstruction does not always lead to wound healing or amelioration of symptoms in patients with PVDs (12).

Previous studies in our laboratory (13, 14) and those of others (9, 31–34) have clearly established that the loss of normal microvascular structure and function parallels the development of metabolic disease. Of particular relevance to the present study is that we have recently demonstrated that rarefaction in the skeletal muscle of the obese Zucker rat (OZR) appears to develop in stages, where an early reduction of microvessel density is well predicted by an oxidant stress- and inflammation-dependent shift in arachidonic acid metabolism toward increasing levels of thromboxane (Tx)A2, with a later stage of rarefaction that is associated with a loss in vascular nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (14). However, any interventions that have been used to improve these vascular outcomes have been relevant for blunting the severity of the vasculopathy that ultimately develops rather than reversing an established compromised condition once it has already developed (16, 18).

The OZR (fa/fa) represents a model of metabolic syndrome that is fundamentally grounded in a mutation in the leptin receptor, leading to severe leptin resistance, chronic hyperphagia, and the ensuing development of severe obesity (2, 11). Tracking with the severe obesity is a steadily worsening glycemic control, a progressive dyslipidemia, and a moderate hypertension, with the additional comorbidities of a growing prooxidant, proinflammation, and prothrombotic state (22). OZRs exhibit high translational relevance to the metabolic syndrome condition in humans (29) and manifest a progressively worsening skeletal muscle microvascular structure and function that parallels that determined in affected humans.

The purpose of the present study was to use two clinically relevant interventions against the further development of established PVDs, increased physical activity/exercise and chronic ingestion of the β-hydroxy β-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor atorvastatin, to determine whether an established impairment to skeletal muscle arteriolar and microvascular structure and function can be reversed toward normal before reaching its maximum severity. For this study, “reversibility” is defined as the effectiveness of the imposed intervention in OZRs to restore the normal level of a measured parameter (e.g., NO bioavailability) to that determined in untreated lean Zucker rats (LZRs). This study tested the hypothesis that, once developed, skeletal muscle microvascular impairments in the OZR model of metabolic syndrome cannot be reversed, as the environment within the microvasculature cannot be modified sufficiently to generate a condition that allows for reversibility. We propose that a deeper understanding of the reversibility of skeletal muscle microvasculopathy that occurs in metabolic disease will provide greater insights into the clinical challenge of most direct relevance to human subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male LZRs and OZRs (Harlan) were fed standard chow and drinking water ad libitum, unless otherwise indicated, and housed in an accredited animal care facility at either the West Virginia University Health Sciences Center (all experimental procedures) or University of Western Ontario (ex vivo vascular experiments only), and all protocols received prior Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. Animals were used for terminal experiments at 13 wk (initial condition) or 20 wk (after the intervention) of age. At 13 wk of age, LZRs and OZRs (n = 6 for each) were either used for terminal experiments (to establish the initial condition within the microcirculation) or placed into one of four groups: 1) time control (rats were housed without intervention and aged to ∼20 wk, n = 6), 2) atorvastatin (25 mg·kg−1·day−1, mixed with food, n = 6; see Ref. 18), 3) treadmill exercise (20 m/min, 5% incline, 60 min/day, 6 days/wk, n = 6; see Ref. 16), and 4) a combination of atorvastatin treatment and treadmill exercise, as described above, to ∼20 wk of age (n = 6). At the time of final usage, after an overnight fast, rats were anesthetized with injections of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip) and received tracheal intubation to facilitate maintenance of a patent airway. In all rats, a carotid artery and an external jugular vein were cannulated for the determination of arterial pressure and for the infusion of supplemental anesthetic or pharmacological agents as necessary. Blood samples were drawn from the venous cannula within ∼20 min after implantation for the determination of insulin concentrations (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), plasma nitrotyrosine levels, and markers of inflammation using commercially available EIA systems (Luminex 100 PS, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Whereas glucose levels were determined at the time of the blood draw (Freestyle, Abbott Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA), all other samples were spun to remove the plasma, which was snap frozen in liquid N2, until they could be analyzed as groups.

Preparation of isolated skeletal muscle resistance arterioles.

In anesthetized rats, before the preparation of the cremaster muscle (below), the intramuscular continuation of the right gracilis artery was identified, the in vivo length and diameter were estimated using an eyepiece micrometer, and the vessel was surgically removed and doubly cannulated (7). Within each arteriole, vessel reactivity was evaluated in response to application of acetylcholine (10−9−10−6 M) or hypoxia (reduction in Po2 from ∼135 to ∼50 mmHg). Subsequently, vessels were treated with tempol (10−4 M) to assess the contribution of vascular oxidant stress to these mechanical responses. At the conclusion of all procedures described above, vessel diameter was determined under Ca2+-free conditions over a range of intraluminal pressures spanning 0 to 160 mmHg (in 20-mmHg increments) for the subsequent calculation of wall mechanics. For these procedures, 5 mmHg was used as the “zero pressure” condition to prevent vessel collapse and to eliminate the potential for creating a vacuum within the vessel.

Preparation of in situ cremaster muscle.

In each rat, the left cremaster muscle was prepared for television microscopy (24). After completion of the preparation, the muscle was superfused with physiological salt solution (PSS), equilibrated with a gas mixture containing 5% CO2 and 95% N2, and maintained at 35°C as it flowed over the muscle at a rate of 2.5–3.0 ml/min. The ionic composition of PSS was as follows (in mM): 119.0 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.18 NaH2PO4, 1.17 MgSO4, 24.0 NaHCO3, and 0.03 disodium EDTA. After an initial postsurgical equilibration period of 30 min, two sets of arterioles and their bifurcations were selected. Proximal (∼75-μm diameter) and distal (∼40-μm diameter) parent arterioles and their immediate daughter branches were selected for investigation in a clearly visible region of the muscle (please see Ref. 17 for a full description). All arterioles chosen for study had walls that were clearly visible, a brisk flow velocity, and active tone, as indicated by the occurrence of significant dilation in response to topical application of 10−5 M adenosine. All arterioles that were studied were located in a region of the muscle that was away from any incision.

Initial evaluations of in situ arteriolar reactivity were assessed by determining mechanical responses (using on-screen videomicroscopy) to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (10−9−10−6 M) and norepinephrine (10−10−10−7 M). Subsequently, diameter and perfusion (using optical Doppler velocimetry) responses of both the “parent” and “daughter” arterioles at either level of the microcirculation were assessed under resting conditions within the cremaster muscle of each rat. All procedures were then repeated after treatment of the in situ cremaster muscle with the antioxidant tempol (10−3 M, within the superfusate, for a minimum of 40 min before any subsequent data collection).

Measurement of vascular NO bioavailability.

From each rat, the abdominal aorta was removed and vascular NO production was assessed using amperometric sensors (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Briefly, aortae were isolated, sectioned longitudinally, pinned in a silastic-coated dish, and superfused with warmed (37°C) PSS equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. An NO sensor (ISO-NOPF 100) was placed in close apposition to the endothelial surface, and a baseline level of current was obtained. Subsequently, increasing concentrations of methacholine (10−10−10−6 M) were added to the bath, and the changes in current were determined. To verify that responses represented NO release, these procedures were repeated after pretreatment of the aortic strip with NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (10−4 M).

Determination of vascular metabolites of arachidonic acid.

Vascular production of 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable breakdown product of PGI2; see Ref. 27) and 11-dehydro-TxB2 (the stable plasma breakdown product of TxA2; see Ref. 8) was assessed in response to challenge with reduced Po2 using pooled arteries (femoral, saphenous, and iliac) from LZRs and OZRs. Pooled arteries from each animal were incubated in microcentrifuge tubes in 1 ml PSS for 30 min under control conditions (21% O2). After this time, the superfusate was removed, stored in a new microcentrifuge tube, and frozen in liquid N2 while a new aliquot of PSS was added to the vessels and the equilibration gas was switched to 0% O2 for the subsequent 30 min. After the second 30-min period, this new PSS was transferred to a fresh tube, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C. Metabolite release by the vessels was determined using commercially available EIA kits for 6-keto-PGF1α and 11-dehydro-TxB2 (Cayman Chemical).

Histological determination of microvessel density.

From each rat, the gastrocnemius muscle from the left leg was removed, rinsed in PSS, and fixed in 0.25% formalin. Muscles were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm cross-sections. Sections were incubated with Griffonia simplicifolia I lectin (GS-1) for the subsequent determination of microvessel density. GS-1 is a general stain that labels all microvessels of <20 μm in diameter (19). Gastrocnemius muscle microvessel density was determined using fluorescence microscopy, as previously described (14).

Preparation of in situ blood perfused gastrocnemius muscle.

In a separate set of age-matched LZRs and OZRs under the conditions described above, the left gastrocnemius muscle of each animal was isolated in situ (13). Heparin (500 IU/kg) was infused via the jugular vein to prevent blood coagulation. Subsequently, an angiocatheter was inserted into the femoral artery, proximal to the origin of the gastrocnemius muscle to allow for bolus tracer injection. Additionally, a small shunt was placed in the femoral vein draining the gastrocnemius muscle that allowed for the diversion of flow into a port that facilitated sampling of the venous effluent. Finally, a microcirculation flow probe (0.5/0.7 PS, Transonic) was placed on the femoral artery to monitor muscle perfusion.

After completion of the surgical preparation and 30 min of self-perfused rest, the muscle was stimulated via the sciatic nerve to contract for 3 min at either 3- or 5-Hz isometric twitch contractions, separated by 15 min of self-perfused rest. Muscle tension development and blood flow were monitored continuously, and arterial and venous blood aliquots were taken within the final 30 s for the determination of blood gas content.

Upon completion of the contraction protocols, the gastrocnemius muscle was allowed ≥20 min of rest for full recovery. At this point, 20 μl of 125I-labeled albumin (10 μCi, Perkin-Elmer, Shelton, CT) was injected as a spike bolus (injection time: <0.5 s) into the arterial angiocatheter, and venous effluent samples were collected at a rate of 1/s for the subsequent 35 s. Venous effluent samples were then immediately transferred into silicate tubes and placed into a gamma-counter for activity determination. To assess the potential for leakage of the labeled albumin from the intravascular space as a source for error, the gastrocnemius muscle was cleared by perfusion with PSS after euthanasia. Subsequent to the determination of mass, the muscle was placed in the counter for determination of residual activity. Residual activity within the gastrocnemius muscle did not exceed 200 counts·min−1·animal−1, a level that was far lower than those determined in the venous blood aliquots.

Mathematical analyses of results.

Arteriolar perfusion in both parent and daughter vessels within the in situ cremaster muscle of LZRs and OZRs was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where Q is arteriolar perfusion (in nl/s), V is the measured red blood cell velocity from the optical Doppler velocimeter (in mm/s; with V/1.6 representing an estimated average velocity assuming a parabolic flow profile) (10), and r is arteriolar radius (in μm) (3).

The total volume perfusion in the daughter arterioles was determined as the sum of the individual perfusion rates, and the proportion of flow within each was determined as the quotient of the individual branch divided by the total; γ is defined as the ratio of the greater of the two flows in the daughter vessel to the total flow in the parent vessel. As an example, if flow distribution was homogeneous between daughters, γ for that bifurcation would be 0.5 in both daughter arterioles, whereas if the proportion of flow in one daughter arteriole was 60%, γ for that bifurcation would be 0.6, with flow distribution being 0.6 in the “high-perfusion” arteriole and 0.4 in the “low-perfusion” arteriole (13). For the present study, after the initial determination of γ (described above), we determined the changes in γ every 20 s over the subsequent 5-min period.

The dilator or constrictor responses of ex vivo microvessels or aortic rings after agonist challenge were fit with the following three-parameter logistic equation:

| (2) |

where y is the change in arteriolar diameter, min and max are the lower and upper bounds of the change in diameter or tension with increasing agonist concentration, respectively, and log ED50 is the logarithm of the agonist concentration (x) at which the response (y) is halfway between the lower and upper bounds.

Vascular NO bioavailability measurements were fit with the following linear regression equation:

| (3) |

where y is the NO concentration, α0 is an intercept term, β1 is the slope of the relationship, and x represents the log molar concentration of methacholine.

The determination of passive arteriolar wall mechanics (used as indicators of structural alterations to the individual microvessel) were based on those used previously (5), with minor modifications. For the calculation of circumferential stress, intraluminal pressure was converted from mmHg to N/m2, where 1 mmHg = 1.334 × 102 N/m2.

Circumferential stress (σ) was then calculated as follows:

| (4) |

where ID is arteriolar inner diameter (in μm) and WT is the wall thickness (in μm) at that intraluminal pressure (PIL). Circumferential strain (ε) was calculated as follows:

| (5) |

where ID5 is the internal arteriolar diameter at the lowest intraluminal pressure (i.e., 5 mmHg).

The stress versus strain relationship from each vessel was fit (ordinary least-squares analyses, r2 > 0.85) with the following exponential equation:

| (6) |

where σ5 is the circumferential stress at ID5 and β is the slope coefficient describing arterial stiffness. Higher levels of β are indicative of increasing arterial stiffness (i.e., requiring a greater degree of distending pressure to achieve a given level of wall deformation).

In specific experiments, 200-μl blood samples were drawn from the carotid artery cannula and femoral vein angiocatheter immediately before and after completion of the muscle contraction periods. Samples were stored on ice until they were processed for blood gas pressures, percent oxygen saturation, and hemoglobin concentration using a Corning Rapidlab 248 blood gas analyzer. Muscle perfusion, arterial pressure, and bulk blood flow through the femoral artery were monitored for 1 min before muscle contractions and throughout the contraction period using a Biopac MP150 with Acqknowledge data-acquisition software at a sampling frequency of 50 Hz. Muscle perfusion and performance data after 3 min of contraction were normalized to gastrocnemius mass, which was not different between LZRs (2.18 ± 0.09 g) and OZRs (2.06 ± 0.10 g). Oxygen content within the blood samples was determined using the following standard equation:

| (7) |

where and are the total content (in ml/dl) and partial pressure of oxygen (in mmHg) of arterial or venous blood (denoted simply as x), respectively. [Hb] is hemoglobin concentration within the blood sample (in g/dl), is the percent oxygen saturation of hemoglobin, and 1.39 and 0.003 are constants describing the amounts of bound and dissolved oxygen in blood. Oxygen uptake across the gastrocnemius muscle was calculated using the Fick equation as follows:

| (8) |

where V̇o2 is oxygen uptake by the gastrocnemius muscle, Q is femoral artery blood flow (in ml·g−1·min−1), and and are arterial and venous oxygen content, respectively.

Analyses of tracer washout curves.

For 125I-labeled albumin washout, four standard parameters describing characteristics of tracer washout curves, including mean transit time (), relative dispersion (RD), skewness (β1), and kurtosis (β2), were computed as functions of the transport function h(t) (4). As described in our recent study (17), the tails of the tracer washout curves were extrapolated in the form of single-exponential time course to allow for computing the four parameters by the integration for a sufficiently long time for convergence (21). In this study, experimentally measured time courses were extrapolated to 100 s, at which was estimated to be <10−9 of the maximum washout tracer activity. The transport function h(t) was estimated from the following equation:

| (9) |

where C(t) is the time course of activity of intravascular tracer in outlet flow exiting the collecting tube. was calculated from experimentally measured washout curves according to the following equation:

| (10) |

The relative dispersion (RD) of h(t) is a measure of the relative temporal spread of h(t) and was computed as the ratio of standard deviation of h(t) to the mean transit time from the following equation:

| (11) |

The skewness (β1) is a measure of asymmetry of h(t) and was computed from the following equation:

| (12) |

Skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of the perfusion distribution. In other words, it is a measure of the extent to which the perfusion distribution is skewed (as opposed to simply being shifted) to higher or lower values of perfusion. Kurtosis (β12) is a measure of deviation of h(t) from a normal distribution and was computed from the following equation:

| (13) |

Kurtosis is a measure of the “sharpness of the peak” of the perfusion distribution. The familiar Gaussian bell-shaped curve has β2 = 0; positive values of β2 indicate a sharper peak than a Gaussian. The four parameters were estimated based on the above equations for each animal in each experimental group.

Determining the effectiveness of the interventions.

The effectiveness of the chronic interventions at improving specific biological outcomes (e.g., biomarkers, vascular function, behavioral scores, etc.) was calculated as follows:

| (14) |

where LZRcontrol and OZRcontrol are the values of the measured parameter under untreated control conditions and OZRintervention is the value of the measured parameter as a result of chronic imposition of a given intervention under age-matched conditions. This determines the percent recovery in a parameter from the control condition in OZRs back to that in control LZRs as a result of the specific intervention.

Statistical analyses of the results.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Statistically significant differences in measured physiological parameters (e.g., arterial pressure, blood flow, and microvessel density), calculated physiological parameters (e.g., slope coefficients as well as upper or lower bounds), and measurements of plasma biomarkers were determined using ANOVA. In all cases, a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test was used when appropriate, and P < 0.05 was taken to reflect statistical significance.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows data describing the baseline and systemic characteristics of the animal groups used in the present study. By 13 wk of age, OZRs were already manifesting multiple elements of metabolic syndrome compared with LZRs, including significant elevations in body mass, plasma insulin, and glucose levels, dyslipidemia, and markers of oxidant stress and inflammation. These differences between LZRs and OZRs were exacerbated by 20 wk of age, with a significant elevation in blood pressure as well. Although single treatment with either atorvastatin or exercise was able to improve specific markers of metabolic syndrome over the duration of the treatment, simultaneous imposition of both treatments was of greater effectiveness in terms of restoring the metabolic profile to that presented in control LZRs.

Table 1.

Data describing the baseline conditions of the animals under the conditions of the present study

| 13 Weeks |

20 Weeks |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LZR | OZR | LZR | OZR | OZR + ATOR | OZR + EXER | OZR + both | |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 106 ± 5 | 114 ± 6* | 104 ± 4 | 130 ± 5* | 129 ± 6* (3.8 ± 1.5%) | 120 ± 5* (38.5 ± 5.4%) | 112 ± 5† (69.2 ± 5.9%) |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 88 ± 6 | 120 ± 7* | 94 ± 5 | 184 ± 8* | 172 ± 6* (13.0 ± 4.8%) | 145 ± 8*† (43.6 ± 6.8%) | 142 ± 7*† (46.8 ± 5.9%) |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.8* | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 1.0* | 6.8 ± 0.7* (16.9 ± 4.8%) | 5.2 ± 0.6* (41.2 ± 6.9%) | 4.8 ± 0.6*† (46.9 ± 6.4%) |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 81 ± 5 | 98 ± 6* | 90 ± 6 | 128 ± 8* | 106 ± 7*† (58.5 ± 4.9%) | 119 ± 6* (24.6 ± 5.8%) | 104 ± 6† (63.0 ± 6.4%) |

| N-tyrosine, ng/ml | 15 ± 2 | 26 ± 4* | 18 ± 4 | 58 ± 6* | 37 ± 5*† (53.0 ± 6.5%) | 35 ± 6*† (58.2 ± 5.1%) | 32 ± 5*† (66.1 ± 6.8%) |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.4* | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.8* | 4.2 ± 0.5*† (54.1 ± 6.2%) | 4.9 ± 0.6*† (42.1 ± 4.9%) | 3.9 ± 0.6*† (58.5 ± 6.4%) |

| Monocyte chemoattractant protein -1, pg/ml | 38.5 ± 4.2 | 102.6 ± 11.5* | 42.4 ± 8.7 | 125.9 ± 10.8* | 70.5 ± 6.9*† (66.5 ± 7.1%) | 85.7 ± 7.9*† (48.5 ± 5.8%) | 66.0 ± 8.4† (72.1 ± 6.8%) |

| IL-1β, pg/ml | 10.1 ± 1.8 | 19.8 ± 3.4* | 11.8 ± 1.8 | 26.8 ± 4.2* | 20.8 ± 2.6* (40.5 ± 4.9%) | 21.2 ± 3.2* (37.8 ± 5.8%) | 20.1 ± 2.6* (45.1 ± 4.9%) |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 40.2 ± 5.1 | 70.8 ± 6.4* | 45.4 ± 5.8 | 84.8 ± 5.8* | 74.0 ± 5.4* (27.4 ± 5.2%) | 72.5 ± 5.9* (31.3 ± 6.2%) | 68.9 ± 6.4*† (40.2 ± 5.9%) |

| IL-10, pg/ml | 19.2 ± 3.9 | 82.9 ± 10.6* | 24.5 ± 5.0 | 126.7 ± 12.4* | 102.6 ± 7.4* (23.5 ± 4.9%) | 96.8 ± 6.8* (29.5 ± 5.1%) | 90.8 ± 10.8*† (35.1 ± 4.9%) |

| Active tone (ex vivo), % | 41 ± 4 | 43 ± 3 | 38 ± 3 | 42 ± 3 | 40 ± 3 | 41 ± 4 | 40 ± 4 |

| Active tone (in situ), % | 35 ± 3 | 36 ± 3 | 28 ± 2 | 32 ± 3 | 33 ± 2 | 35 ± 3 | 34 ± 4 |

| Muscle blood flow at rest, ml·g−1·min−1 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 |

| Mean transit time, g/g | 354 ± 19 | 345 ± 17 | 388 ± 20 | 376 ± 19 | 380 ± 16 | 374 ± 20 | 384 ± 22 |

| Arteriovenous oxygen difference, ml/ml | 0.052 ± 0.003 | 0.049 ± 0.004 | 0.051 ± 0.005 | 0.041 ± 0.003 | 0.048 ± 0.004 (0.0 ± 4.8%) | 0.047 ± 0.005 (33.3 ± 6.7%) | 0.049 ± 0.003* (33.3 ± 7.2%) |

| Oxygen uptake at rest, ml·g−1·min−1 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 0.004 ± 0.001* | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6 rat/sgroup. LZR, lean Zucker rats; OZR, obese Zucker rats; ATOR, atorvastatin; EXER, treadmill exercise. Data inside the parentheses represent the extent to which the relevant intervention restored the normal level of the parameter. Please see text for details.

P < 0.05 vs. LZRs at that age;

P < 0.05 vs. OZRs at that age.

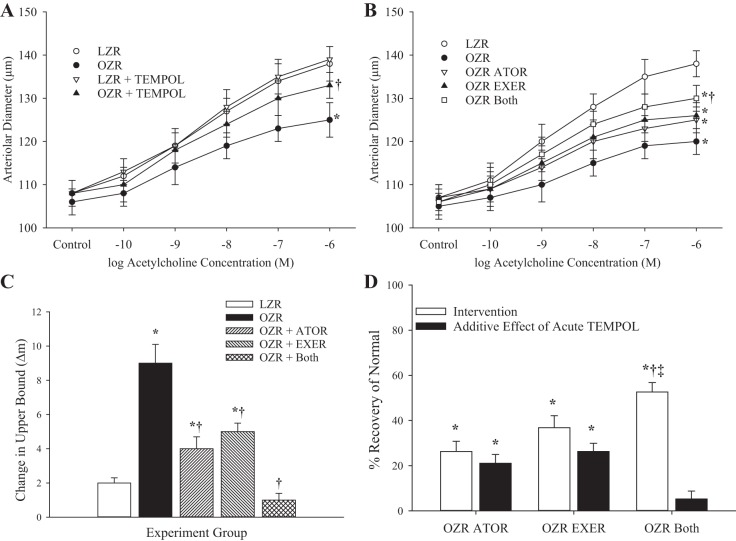

Figure 1 shows data describing the dilator reactivity of ex vivo gracilis muscle resistance arterioles in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine in the present study. Compared with responses in LZRs, dilator reactivity in arterioles of OZRs at 13 wk to acetylcholine was significantly reduced (Fig. 1A). Acute treatment of the vessels with tempol had minimal impact on responses in LZRs but improved reactivity in OZR arterioles. By 20 wk of age, the difference in acetylcholine-induced reactivity was pronounced between LZRs and OZRs (Fig. 1B). Whereas chronic treatment with atorvastatin or exercise improved responses to acetylcholine in OZRs, the combination of the two treatments resulted in the greatest restoration of dilator responses. Figure 1C shows data describing the impact of acute treatment with tempol on the acetylcholine-induced gracilis arteriolar dilation in all groups of rats at 20 wk. Whereas tempol had negligible impact on responses in vessels from LZRs and the greatest impact on dilator responses in vessels from OZRs, the impact on responses in arterioles from OZRs that had been treated with atorvastatin, exercise, or both was blunted compared with those in untreated OZRs. The ability of the chronic interventions to restore normal dilator reactivity (determined in LZRs) from the maximum impairment (determined in OZRs) is shown in Fig. 1D. Whereas both atorvastatin and exercise resulted in a significant restoration of normal function in OZRs, with a significant additive benefit of acute tempol treatment, the combination of both interventions resulted in the greatest degree of recovery in acetylcholine-induced responses with the smallest additional benefit from an acute treatment with the antioxidant.

Fig. 1.

Data (means ± SE) describing the dilator reactivity of ex vivo gracilis muscle resistance arterioles in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine. A: data from lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 wk of age under untreated conditions and after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol.B: data from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk of age under control conditions and after 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. C: change in the upper bound of the logistic equation fit to the curves shown in B after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. D: extent to which the different interventions restored normal function and the additive benefit of acute treatment with tempol. n = 6 for all groups. In A–C, *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs and †P < 0.05 vs. OZRs. In D, *P < 0.05 vs. no change, †P < 0.05 vs. the OZR ATOR group, and ‡P < 0.05 vs. the OZR EXER group. Please see text for details.

Dilator responses of gracilis arterioles in response to hypoxia from LZRs and OZRs at 13 wk are shown in Fig. 2A. Hypoxic dilation in vessels from OZRs was significantly reduced compared with that in LZRs, although acute treatment of the vessel with tempol improved responses in vessels from OZRs only. By 20 wk, the impaired hypoxic dilation in arterioles from OZRs was exacerbated, and chronic treatments with exercise or atorvastatin + exercise resulted in significant improvements (atorvastatin alone did not significantly improve responses; Fig. 2B). Acute treatment of gracilis arterioles from the groups of rats at 20 wk of age with tempol had a significant impact on hypoxic dilation in untreated OZRs and in OZRs treated with chronic atorvastatin or exercise only (Fig. 2C), whereas the effectiveness of the interventions on restoring normal function was similar between atorvastatin and exercise, with the combination of both being most effective, and the additional benefit of acute tempol treatment was lowest in the atorvastatin + exercise group (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Data (means ± SE) describing the dilator reactivity of ex vivo gracilis muscle resistance arterioles in response to reduced Po2 in the chamber (hypoxia). A: data from lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 wk of age under untreated conditions and after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. B: data from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk of age under control conditions and after 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. C: change in the dilator response shown in B after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. D: extent to which the different interventions restored normal function and the additive benefit of acute treatment with tempol. n = 6 for all groups. In A–C, *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs and †P < 0.05 vs. OZRs. In D, *P < 0.05 vs. no change, †P < 0.05 vs. the OZR ATOR group, and ‡P < 0.05 vs. the OZR EXER group. Please see text for details.

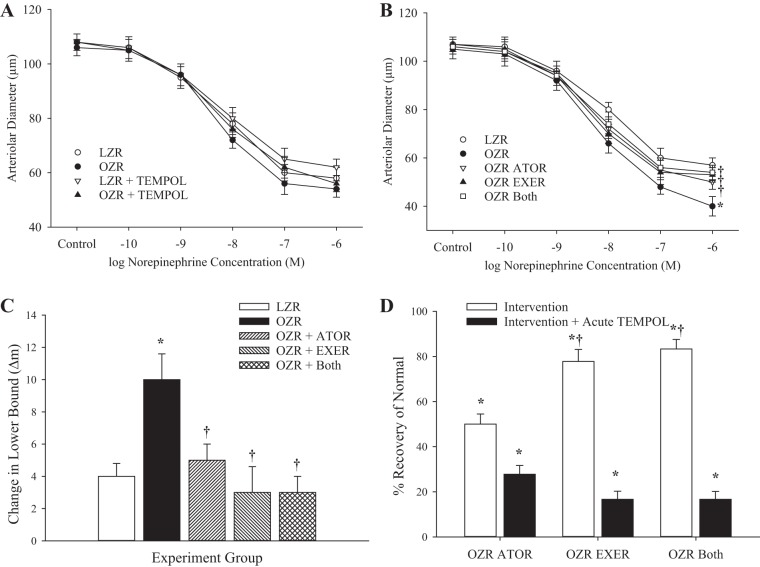

The constriction of ex vivo skeletal muscle resistance arterioles in 13-wk-old LZRs and OZRs in response to increasing concentrations of norepinephrine is shown in Fig. 3A. At this age, there was no difference in vasoconstriction to increasing concentrations of the adrenergic agonist between the groups. However, by 20 wk of age (Fig. 3B), constrictor responses to norepinephrine were significantly greater in OZRs versus LZRs, and this difference in reactivity was nearly abolished by chronic treatment with atorvastatin, exercise, or both. Acute treatment of these groups with tempol improved responses in untreated OZRs but had minimal impact on constrictor reactivity of gracilis arterioles from all other groups (Fig. 3C). The extent to which chronic atorvastatin, exercise, or both interventions restored normal norepinephrine-induced reactivity is shown in Fig. 3D. Compared with OZRs at 20 wk, chronic imposition of all three interventions resulted in an excellent recovery to normal constriction to norepinephrine, with minimal added benefit from acute treatment with tempol.

Fig. 3.

Data (means ± SE) describing the constrictor reactivity of ex vivo gracilis muscle resistance arterioles in response to increasing concentrations of norepinephrine. A: data from lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 wk of age under untreated conditions and after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. B: data from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk of age under control conditions and after 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. C: change in the lower bound of the logistic equation fit to the curves shown in B after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. D: extent to which the different interventions restored normal function and the additive benefit of acute treatment with tempol. n = 6 for all groups. In A–C, *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs and †P < 0.05 vs. OZRs. In D, *P < 0.05 vs. no change and †P < 0.05 vs. the OZR ATOR group. Please see text for details.

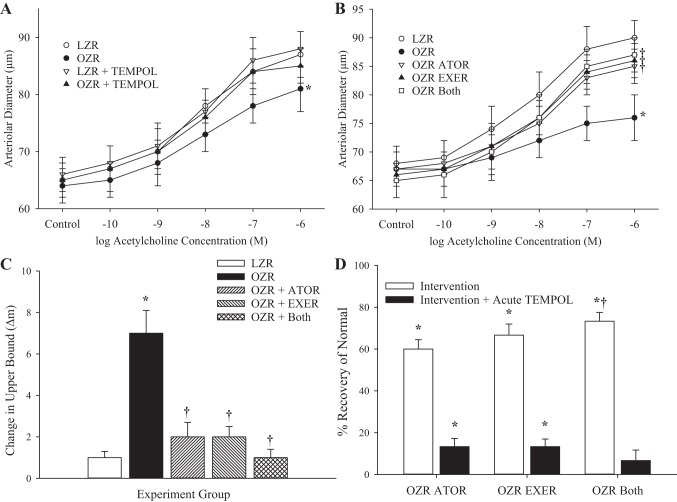

The dilator responses of proximal in situ cremasteric arterioles to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine in LZRs and OZRs at 13 wk of age are shown in Fig. 4A, where responses were significantly reduced in vessels in OZRs, and this difference was largely abolished after treatment of the cremaster muscle with tempol. In OZRs at 20 wk, whereas the differences in acetylcholine-induced dilation with LZRs were increased, chronic imposition of atorvastatin, exercise, or both significantly improved responses (Fig. 4B) and reduced the beneficial impact of acute tempol treatment on dilator reactivity (Fig. 4C). Additionally, chronic imposition of atorvastatin, exercise, or both from 13 wk of age (with “both” being most effective) significantly restored normal vascular reactivity to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (Fig. 4D). For distal arterioles of in situ cremaster muscle, the patterns in the data were extremely similar to those for proximal arterioles (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Data (means ± SE) describing the dilator reactivity of in situ cremaster muscle resistance arterioles in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine. A: data from from lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 wk of age under untreated conditions and after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. B: data from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk of age under control conditions and after 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. C: change in the upper bound of the logistic equation fit to the curves shown in B after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. D: extent to which the different interventions restored normal function and the additive benefit of acute treatment with tempol. n = 6 for all groups. In A–C, *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs and †P < 0.05 vs. OZRs. In D, *P < 0.05 vs. no change and †P < 0.05 vs. the OZR ATOR group. Please see text for details.

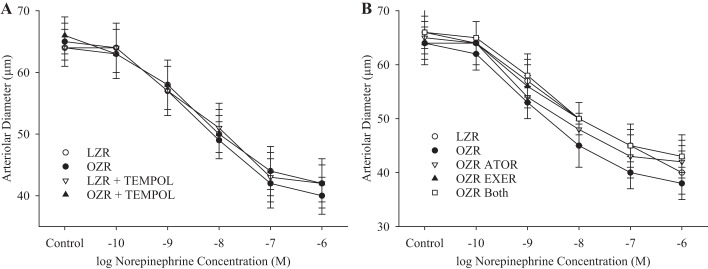

Figure 5 shows data describing the changes in constrictor responses to increasing concentrations of norepinephrine for in situ cremasteric arterioles. Whereas there were minimal differences in responses at 13 wk of age between strains (Fig. 5A), the differences at 20 wk of age were somewhat more extensive, there were no differences in reactivity that were demonstrated to be consistently statistically significant (Fig. 5B). As described above, for distal arterioles of in situ cremaster muscle, the norepinephrine-induced constriction, although potent, did not demonstrate statistically significant differences between LZRs and OZRs at either age range and as such were not formally presented (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Data (means ± SE) describing the constrictor reactivity of in situ cremaster muscle resistance arterioles in response to increasing concentrations of norepinephrine. A: data from from lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 wk of age under untreated conditions and after acute treatment with the antioxidant tempol. B: data from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk of age under control conditions and after 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. n = 6 for all groups.

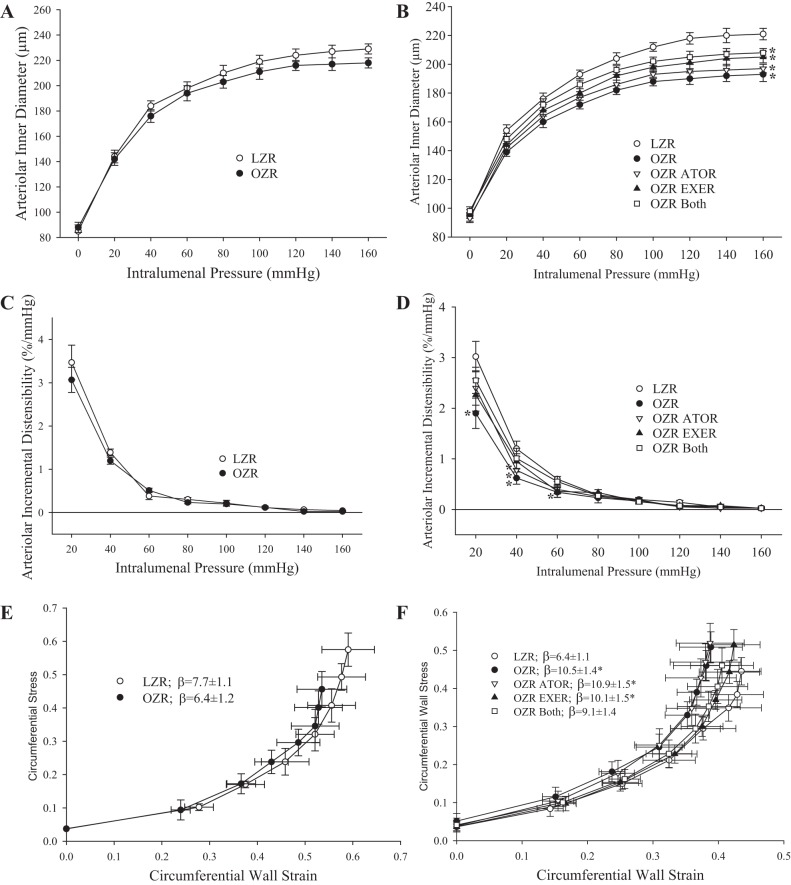

The impact of chronic interventions on the reversibility of altered wall mechanics in LZR and OZR gracilis arterioles are shown in Fig. 6. At 13 wk of age, there were no significant differences in the inner diameter of gracilis arterioles (Fig. 6A), their incremental distensibility (Fig. 6C), or the slope coefficient (β) from their stress versus strain relationship (Fig. 6E). By 20 wk of age, arterioles from OZRs exhibited a reduced passive inner diameter compared with those from LZRs (Fig. 6B), with a reduced incremental distensibility (Fig. 6D) and a significant left shift of the stress versus strain relationship (Fig. 6F). Chronic interventions with atorvastatin and exercise, alone or in combination, were largely ineffective at blunting this effect (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Mechanics of the wall of ex vivo gracilis muscle resistance arterioles under Ca2+-free conditions with increasing intralumenal pressure. Data are presented as means ± SE. A: inner diameter of gracilis muscle resistance arterioles from lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 wk. B: inner diameter of gracilis muscle resistance arterioles from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk under control conditions and in response to 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. C: incremental distensibility of gracilis arterioles from LZRs and OZRs at 13 wk. D: incremental distensibility of gracilis arterioles from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk under control conditions and in response to 7 wk of intervention with ATOR, EXER, or both. E: circumferential stress versus strain relationship between gracilis arterioles from LZRs and OZRs at 13 wk with the determination of the slope coefficient (β). F: stress versus strain relationship between gracilis arterioles from LZRs and OZRs at 20 wk under control conditions and in response to 7 wk of intervention with ATOR, EXER, or both with the determination of β. n = 6 for all groups. *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs. Please see text for details.

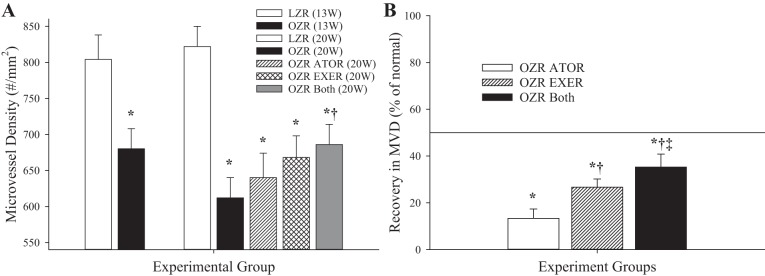

Figure 7 shows data describing the gastrocnemius muscle microvessel density (Fig. 7A) and the extent of recovery in microvessel density as a result of the chronic interventions (Fig. 7B) in LZRs and OZRs. At 13 wk of age, there was a reduction in microvessel density between LZRs and OZRs, which became much more pronounced by 20 wk of age. This difference was largely unaffected by chronic treatment with atorvastatin and only marginally affected by chronic exercise from 13 wk of age in OZRs. However, combined imposition of both interventions resulted in a significant improvement in skeletal muscle microvessel density in OZRs.

Fig. 7.

Microvessel density (MVD) within gastrocnemius muscles of lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) under the conditions of the present study. A: data (means ± SE) for animals at 13 and at 20 wk of age under control (untreated) conditions and in response to 7 wk of atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both interventions imposed concurrently. B: extent to which the different chronic interventions restored normal levels of MVD in OZRs. n = 6 for all groups. In A, *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs and †P < 0.05 vs. OZRs. In B, *P < 0.05 vs. no change, †P < 0.05 vs. the OZR ATOR group, and ‡P < 0.05 vs. the OZR EXER group. Please see text for details.

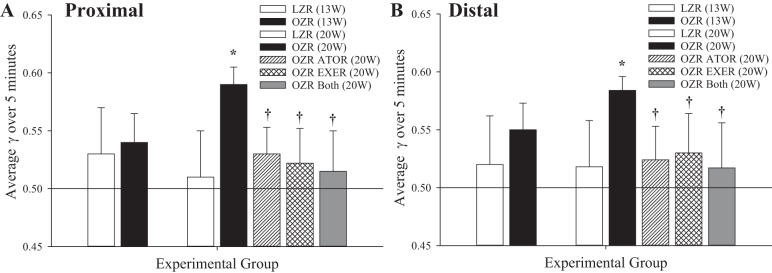

Figure 8 shows data describing the perfusion distribution coefficient (γ) in both the proximal (Fig. 8A) and distal (Fig. 8B) cremasteric microcirculation. These data suggest that there were minimal differences in the average magnitude of γ between LZRs and OZRs at 13 wk of age, although the temporal variability in γ over the data collection window was reduced in OZRs. In contrast, γ was increased, and its variability was reduced, in OZRs at 20 wk of age versus LZRs, and chronic imposition of atorvastatin, exercise, or both from 13 wk of age resulted in improvements to γ and a greater degree of variability compared with responses in untreated OZRs. These results were consistent in both proximal (Fig. 8A) and distal (Fig. 8B) arteriolar bifurcations within the cremasteric microcirculation.

Fig. 8.

Perfusion heterogeneity (γ) at proximal (∼70-μm diameter; A) and distal (∼30-μm diameter; B) arteriolar bifurcations within in situ cremaster muscles of lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) under the conditions of the present study. Data (means ± SE) are presented for animals at 13 and at 20 wk of age under control (untreated) conditions and in response to 7 wk of atorvastatin (ATOR), exercise (EXER), or both interventions imposed concurrently (A). n = 6 for all groups. *P < 0.05 between variability in group vs. LZR variability; †P < 0.05 between variability in this group vs. OZR variability. Please see text for details.

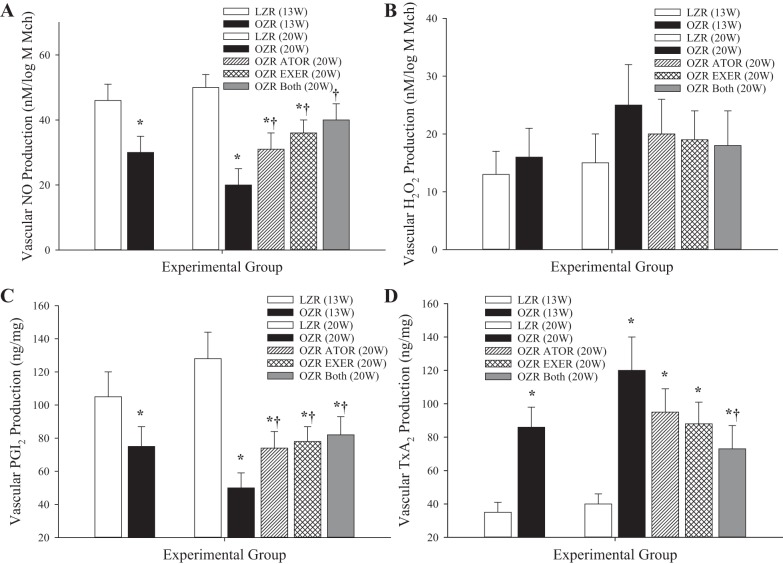

Figure 9 shows the bioavailability of vasoactive metabolites that have been previously demonstrated to play a contributing role in the vascular phenotypes discussed above. Vascular NO bioavailability (Fig. 9A) was reduced in arteries of OZRs compared with LZRs at 13 wk, and this was exacerbated by 20 wk. Chronic intervention with atorvastatin, exercise, or both resulted in a significant improvement in levels of NO bioavailability at 20 wk of age in OZRs. Vascular H2O2 levels, elevated in arteries of OZRs versus LZRs at 20 wk of age (Fig. 9B), demonstrated a higher degree of variability and, although they presented a mirrored trend compared with NO, did not produce a consistently significant outcome subsequent to the interventions. A similar pattern to that for NO was determined for PGI2 bioavailability (Fig. 9C), although the ability of the interventions to restore normal levels was less robust. Conversely, TxA2 bioavailability (Fig. 9D) was significantly increased by 13 wk of age in arteries of OZRs compared with LZRs, and this elevation was reduced only at 20 wk after combined imposition of atorvastatin and exercise from 13 wk of age in OZRs.

Fig. 9.

Data describing the bioavailability of signaling molecules associated with healthy and impaired vascular function. Data (means ± SE) are presented for the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO; A), H2O2 (B), PGI2 (C), and thromboxane A2 (TxA2; D). n = 6 for all groups. *P < 0.05 vs. lean Zucker rats (LZRs); †P < 0.05 vs. obese Zucker rats (OZRs). Please see text for details.

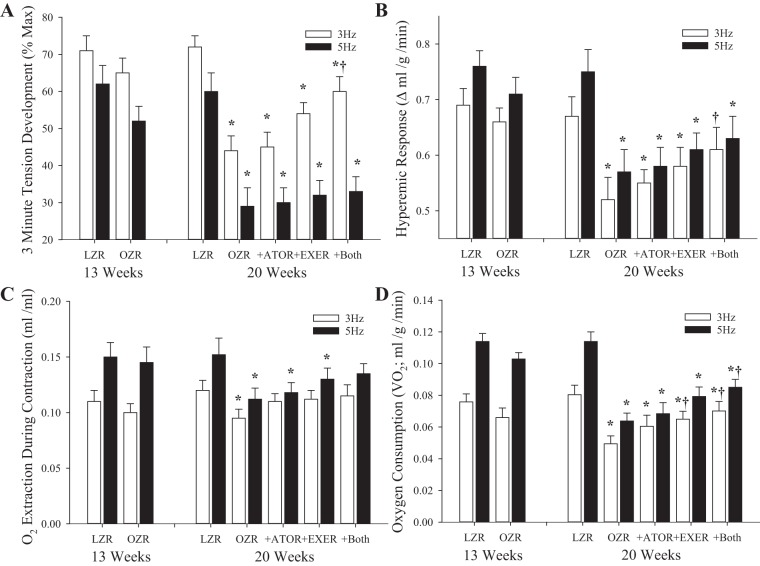

The results of the in situ gastrocnemius muscle performance experiments are shown in Fig. 10. At 13 wk of age, OZRs demonstrated an accelerated muscle fatigue rate compared with LZRs after 3 min of contraction at both 3 and 5 Hz (isometric twitches), with the difference being exacerbated at 5 Hz (Fig. 10A). This impaired muscle performance was increased at 20 wk of age and was not significantly impacted by atorvastatin or exercise, but only in response to the combination intervention. The functional hyperemic response to muscle contraction was similar between LZRs and OZRs at 13 wk but was attenuated by 20 wk for both 3- and 5-Hz contractions (Fig. 10B). All three interventions were successful at significantly improving the bulk hyperemic response to both levels of increased metabolic demand after chronic intervention from 13 wk. Oxygen extraction (Fig. 10C) and V̇o2 (Fig. 10D) across the muscle, although comparable in LZRs and OZRs at 13 wk, were reduced by 20 wk of age. Although atorvastatin and exercise alone resulted in mild improvements that were not statistically significant for extraction of V̇o2, the combination of the two interventions restored both parameters to levels that were not significantly different from those in LZRs (at 3 Hz only).

Fig. 10.

Vascular responses and contractile performance of in situ skeletal muscles of lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 and at 20 wk of age under control (untreated) conditions and in response to 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), treadmill exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. Data (means ± SE) are presented from the animal groups in response to 3 min of muscle contraction at 3 or 5 Hz (isometric twitch). Data are presented for the percentage of the peak force development after 3 min of the contraction bout (A), the hyperemic responses to muscle contraction (B), oxygen extraction across the gastrocnemius muscle (C), and oxygen consumption across the gastrocnemius muscle (D). n = 6 for all groups. *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs; †P < 0.05 vs. OZRs. Please see text for details.

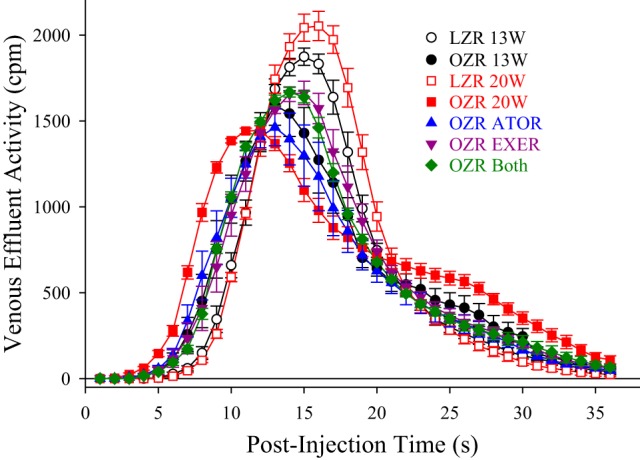

Figure 11 shows data describing the average tracer washout from the in situ gastrocnemius preparation under rest conditions across the different experiment groups of the present study. The appearance of 125I-labeled albumin in the venous effluent draining the gastrocnemius muscle in all groups in the present study is shown in Fig. 11. Figure 12 shows data describing the aggregate washout curves. Mean transit time of the tracer across the gastrocnemius was very similar across all groups, suggesting that the relationship between bulk blood flow to the gastrocnemius muscle and vascular volume in the different groups was not significantly different in the present study (Fig. 12A). The RD of tracer across the muscle (Fig. 12B) was elevated in untreated OZRs at 20 wk of age compared with all other groups, which is suggestive of an increased perfusion heterogeneity throughout the microcirculation of the gastrocnemius muscle. Whereas treatment with atorvastatin was ineffective at restoring RD, chronic exercise, alone or in combination with atorvastatin, was superior at restoring RD toward levels determined in age-matched LZRs. Both the skewness (Fig. 12C) and kurtosis (Fig. 12D) of the tracer washout curves were reduced in OZRs compared with age-matched LZRs, and these shifts in the washout patterns were improved toward those determined in LZRs as a result of either atorvastatin, exercise, or both interventions imposed concurrently.

Fig. 11.

Data describing the tracer washout of 125I-labeled albumin from the in situ gastrocnemius muscles of lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) under the conditions of the present study. Data (means ± SE) are presented for LZRs and OZRs at 13 and at 20 wk of age under control (untreated) conditions and in response to 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), treadmill exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. n = 5 for each group. Please see text for details.

Fig. 12.

Data (means ± SE) describing four characteristics of the washout of 125I-labeled albumin from the in situ gastrocnemius muscle of lean and obese Zucker rats (LZRs and OZRs, respectively) at 13 and at 20 wk of age under control (untreated) conditions and in response to 7 wk of intervention with atorvastatin (ATOR), treadmill exercise (EXER), or both concurrently. Data are shown for the mean transit time of the washout (A), relative dispersion of the washout (B), distribution skewness (C), and kurtosis (D). n = 5 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. LZRs; †P < 0.05 vs. OZRs. Please see text for details.

DISCUSSION

The powerful association between chronic metabolic disease and the increased risk for the development of PVDs has been well known for many years. Although there have been many studies seeking to understand the mechanisms underlying the compromised vascular function under these conditions or how interventional strategies could serve to blunt the development of the poor vascular outcomes (for a review, please see Ref. 33), an understanding of the outright reversibility of established vasculopathy in translationally relevant models has been more elusive. This is particularly troubling, as it is this challenge that is most clinically relevant, where patients present themselves in a clinical setting only once they have already experienced the manifestations of PVDs (e.g., rapid muscle fatigue, pain upon exertion, etc.). The purpose of the present study was to use the OZR model of metabolic syndrome at an age where impairments to skeletal muscle microvascular structure and function have already been established and where impairments to hyperemic responses and muscle performance are still mild to determine the extent to which clinically relevant interventions could improve not only microvascular reactivity and structure but also muscle fatigue and hyperemia with increased metabolic demand.

At 13 wk of age, the presence of metabolic disease in OZRs was associated with impaired endothelial function, reduced microvessel density, and initial evidence of impaired muscle performance and active hyperemic responses. As the severity of metabolic syndrome progressed, impairments to microvascular structure and function increased to include an increased stiffening of the arteriolar wall, an increasing (and increasingly stable) heterogeneity of perfusion at arteriolar bifurcations, and a worsening of skeletal muscle perfusion and oxygen exchange. Although this is not novel information and has been previously described, it does set the appropriate context for the present study; the vasculopathy associated with the metabolic syndrome at 13 wk of age was present, was sufficient to impact skeletal muscle performance, and continued to evolve naturally over the subsequent 7 wk to further compromise muscle blood flow and performance.

Chronic ingestion of atorvastatin from 13 wk of age or chronic imposition of treadmill exercise demonstrated some effectiveness at improving vascular, and by extension muscle blood flow and performance, outcomes in OZRs compared with no intervention, but even the combination of the two had clear limits on effectiveness. Under all three interventions, with the combination of both atorvastatin and exercise being most effective, the improvement to the vasoactive metabolite profile associated with the improvement in oxidant stress and inflammation levels was critical for improving vascular reactivity to acetylcholine, hypoxia, and norepinephrine. In addition, there were some improvements to microvessel density, although the extent of the rarefaction even with the combined interventions remained considerable in OZRs despite 7 wk of aggressive treatment. Furthermore, there was very little change in the progression of altered wall mechanics in the arterioles of OZRs, regardless of intervention.

Although the structure of the microvascular networks was resistant to improvement after intervention, there was an improvement in both the magnitude and variability of γ throughout the microcirculation of OZRs with chronic atorvastatin, exercise, or both. This was evident in both the direct observations of the microvascular networks in the cremaster or using the tracer washout curve analyses for the labeled albumin. These results suggest that the increased heterogeneity of perfusion distribution that accompanies progressive metabolic disease in OZRs can be partially reversed with aggressive intervention, even with established dysfunction. The combination of these improvements to reactivity, and especially to perfusion distribution, was associated with improvements to muscle performance, hyperemic responses, and oxygen exchange for skeletal muscle in OZRs. However, because recovery was most clearly evident at 3-Hz contraction, as it seemed that 5-Hz contraction frequency has been too severe a challenge for any significant recovery to have been evident.

A study of this scope and focus immediately lends itself to a wide array of provocative questions, some of which we will attempt to address or clarify in the succeeding paragraphs. Obviously, one question that immediately comes to mind is the timing of the intervention and its duration. We elected to use 13 wk of age for two major reasons. First, vasculopathy was established at this age and was beginning to impact muscle blood flow and performance, so this was considered to be the earliest time point that was relevant for “reversing” rather than for “blunting development” of vascular dysfunction. Second, in preliminary studies, 15 wk of age was also considered as an option for the initiation of intervention due to the greater establishment of vasculopathy. However, it was rapidly determined that the exercise intervention was not feasible, as OZRs at that age were not able to consistently exercise without invoking a level of attrition that made the experiments unrealistic.

The use of the 7 wk of intervention was selected for two reasons as well. First, using a 4-wk intervention, which would bring animals to the ∼17-wk age range that we have historically used, was not considered to be of sufficient duration to determine any meaningful outcome. Second, using a 7-wk intervention duration brings us to 20-wk-old OZRs, which we have determined is the maximum age we have been able to use before changes to skeletal muscle function (e.g., Ca2+ handling, half-relaxation time, maximal twitch tension, and fiber type distribution) become too great to allow for an accurate interpretation of the data.

The failure of arteriolar wall mechanics to demonstrate any significant improvement with intervention, given its lack of presence at 13 wk of age in OZRs, could actually be considered as an appearance of the dysfunction despite the interventions and was a particularly striking observation of the present study. Although the mechanisms underlying the progressive reduction in vascular wall distensibility with metabolic disease (in OZRs and in other models) are a continuing area of active investigation, it may be that the combination of atorvastatin and exercise issimply “off target” for preventing vascular wall remodeling. In our previous studies, the increased stiffness of the arteriolar wall in OZRs was associated more with the development of hypertension rather than with impaired glycemic control or dyslipidemia (18), and previous studies using interventions specifically targeted at reducing blood pressure have been more effective at moderating the changes to vascular wall structure and mechanics (30).

The relatively modest responses at improving microvessel density are also intriguing, as previous studies have clearly demonstrated that chronic atorvastatin treatment and/or exercise from a relatively young age and severity of metabolic syndrome were effective at blunting rarefaction severity in skeletal muscle of OZRs (14). However, it seems plausible that the use of the 13-wk age for the start of intervention, although justifiable from the perspective of translational relevance, may have missed the window when the extent of rarefaction was most modifiable. In a recent study examining the temporal nature and mechanistic bases of rarefaction in skeletal muscle of OZRs, it was evident that the initial phase of rarefaction occurs before 10–12 wk of age in OZRs and was most closely predicted by the severity of both inflammation and vascular production of TxA2 (14). For maximal effectiveness, it was proposed that interventions against rarefaction should be initiated before 10 wk of age in OZRs, although this is somewhat problematic, as there is no functional phenotype associated with these early changes to microvessel density that has been identified. Regardless, it seems likely that the optimal window for intervening against microvessel loss in skeletal muscle rarefaction in OZRs may have been missed with interventions starting only after 13 wk of age. However, it must be emphasized that we have used only a 7-wk intervention duration. Whether a longer duration of atorvastatin treatment, exercise regimen, or both (or some other intervention) would result in a greater degree of reversibility of the skeletal muscle microvascular impairments will require dedicated study.

An additional issue that requires some comment is the observation that, although there were significant improvements to the reactivity of arterioles from the gracilis muscle, muted improvements to the microvessel density of the gastrocnemius muscle, and improvements to the performance, blood flow, oxygen handling, and tracer washout kinetics indicative of a less heterogeneous perfusion distribution within the in situ gastrocnemius muscle of OZRs, this study also presents data describing the improvement to the hemodynamic control of perfusion distribution in the in situ cremaster muscle, a tissue that is not involved in the exercise training regimen and does not directly benefit from the effects of the chronic exercise (with or without concurrent atorvastatin therapy). This provides strong support that the improved systemic effects of chronic exercise therapy in OZRs, which can include an improved endocrine, oxidant stress, and proinflammation status, can be highly effective in terms of improving vascular function, and may work in combination with direct effects in the exercising muscles of interest to produce a system-wide improvement to vascular health under conditions of metabolic syndrome. However, caution must be used when interpreting some of the results of the present study. The measurement of vascular metabolites that can impact the regulation of tone used larger arteries and not resistance arterioles. Although this allowed us to reduce animal number and provide insight into “within-animal” comparisons, it must be remembered that vascular environments are different between larger arteries and resistance arterioles, with the potential for introducing inaccuracy in terms of assessing the importance of the metabolites to tone regulation.

Given the results of the present study, it may be appropriate to speculate on not just the effect of the interventions on the potential for reversibility of established vasculopathy (or potential mechanisms) but also on whether the effects of these interventions can be additive or potentially synergistic. It has been well established that both atorvastatin and exercise can improve anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacity, thereby improving vascular function and health outcomes through those mechanistic pathways. However, the results from the present study suggest that this effect is more diverse than a single issue, such as improved NO bioavailability, and may also include a partial restoration of vascular arachidonic acid metabolism. This beneficial effect appears to be localized primarily to the endothelial cell, as responses to vascular smooth muscle-dependent stimuli were largely unaffected. Furthermore, over the time course of the present study, the impacts of the interventions did not significantly reverse vascular structure at either the individual vessel or whole network levels of resolution. Although it is possible that a longer-duration intervention might improve the structural characteristics of the vasculature, we may simply have intervened outside of the most appropriate window of time to elicit a beneficial outcome (14). Regardless, although the design of the present study does not allow for a rigorous assessment of whether the interventions were additive or synergistic at this time, it is clear that the combination therapy is sufficiently robust in that it helps to restore not just hyperemic responses and muscle fatigue rates but also perfusion distribution and thus oxgen delivery patterns within the skeletal muscle.

In summary, the results of the present study provide compelling evidence that the imposition of two clinically relevant interventions (atorvastatin and chronic exercise), alone or in combination, in OZRs with a preexisting established vasculopathy can result in improvements to specific indexes of vascular reactivity, hemodynamics, blood flow, oxygen handling, and muscle performance. Furthermore, these improvements appear to be clearly tied to the effects of both interventions on enhancing oxidant stress and proinflammation severity system wide. The use of statins has been shown to result in improved patency and limb salvage rates in patients undergoing revascularization for limb ischemia (1). The specific mechanisms underlying this effect remain unclear. Perhaps these improvements in microvascular dysfunction observed in this animal model help to explain this clinical association in humans. Indexes of altered vascular structure, both at the individual vessel and whole network levels of resolution, were more resistant to reversibility with the selected interventions and their duration, although determining whether this represents specific procedural issues with the present study or simply processes that are more difficult to reverse will require further investigation. Regardless, the results of the present study provide compelling insights and provocative direction for future study into the reversibility of established vasculopathies under conditions of chronic metabolic disease and may have implications for primary and secondary prevention of PVDs.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grants IRG 14330015 and EIA 0740129N, National Institutes of Health Grants RR-2865AR and R01-DK-64668, the Center for Cardiovascular and Respiratory Sciences at West Virginia University, and the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Western Ontario.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.A.L. and J.C.F. conceived and designed research; K.A.L. and J.C.F. performed experiments; K.A.L., S.J.F., F.W., M.T.L., R.W.W., and J.C.F. analyzed data; K.A.L., S.J.F., L.D., N.T., F.W., M.T.L., R.W.W., and J.C.F. interpreted results of experiments; K.A.L. and J.C.F. prepared figures; K.A.L., S.J.F., L.D., N.T., F.W., M.T.L., R.W.W., and J.C.F. edited and revised manuscript; K.A.L., S.J.F., L.D., N.T., F.W., M.T.L., R.W.W., and J.C.F. approved final version of manuscript; S.J.F., L.D., N.T., F.W., M.T.L., R.W.W., and J.C.F. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was the result of many individuals working over the period of years, with each contributing in their own way to the data set. We acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Adam Goodwill, Dr. Phoebe Stapleton, Dr. Joshua Butcher, Dr. Steven Brooks, and Milinda James to this study as well as multiple other student trainees within the laboratory over many years.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiello FA, Khan AA, Meltzer AJ, Gallagher KA, McKinsey JF, Schneider DB. Statin therapy is associated with superior clinical outcomes after endovascular treatment of critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 55: 371–380, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aleixandre de Artiñano A, Miguel Castro M. Experimental rat models to study the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr 102: 1246–1253, 2009. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509990729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker M, Wayland H. On-line volume flow rate and velocity profile measurement for blood in microvessels. Microvasc Res 7: 131–143, 1974. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(74)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassingthwaighte JB, Goresky CA. Modeling in the analysis of solute and water exchange in the microvasculature. In: Handbook of Physiology, The Cardiovascular System, Microcirculation Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society, 1984, p. 549–626. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumbach GL, Hajdu MA. Mechanics and composition of cerebral arterioles in renal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 21: 816–826, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.21.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behnke BJ, Kindig CA, McDonough P, Poole DC, Sexton WL. Dynamics of microvascular oxygen pressure during rest-contraction transition in skeletal muscle of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H926–H932, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00059.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butcher JT, Goodwill AG, Frisbee JC. The ex vivo isolated skeletal microvessel preparation for investigation of vascular reactivity. J Vis Exp: 3674, 2012. doi: 10.3791/3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catella F, Healy D, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. 11-Dehydrothromboxane B2: a quantitative index of thromboxane A2 formation in the human circulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83: 5861–5865, 1986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clough GF, Kuliga KZ, Chipperfield AJ. Flow motion dynamics of microvascular blood flow and oxygenation: Evidence of adaptive changes in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus/insulin resistance. Microcirculation 24: e12331, 2017. doi: 10.1111/micc.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MJ. Determination of volumetric flow in capillary tubes using an optical Doppler velocimeter. Microvasc Res 34: 223–230, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(87)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellmann L, Nascimento AR, Tibiriça E, Bousquet P. Murine models for pharmacological studies of the metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Ther 137: 331–340, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsythe RO, Brownrigg J, Hinchliffe RJ. Peripheral arterial disease and revascularization of the diabetic foot. Diabetes Obes Metab 17: 435–444, 2015. doi: 10.1111/dom.12422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frisbee JC, Butcher JT, Frisbee SJ, Olfert IM, Chantler PD, Tabone LE, d’Audiffret AC, Shrader CD, Goodwill AG, Stapleton PA, Brooks SD, Brock RW, Lombard JH. Increased peripheral vascular disease risk progressively constrains perfusion adaptability in the skeletal muscle microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H488–H504, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00790.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisbee JC, Goodwill AG, Frisbee SJ, Butcher JT, Brock RW, Olfert IM, DeVallance ER, Chantler PD. Distinct temporal phases of microvascular rarefaction in skeletal muscle of obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1714–H1728, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00605.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisbee JC, Goodwill AG, Frisbee SJ, Butcher JT, Wu F, Chantler PD. Microvascular perfusion heterogeneity contributes to peripheral vascular disease in metabolic syndrome. J Physiol 594: 2233–2243, 2016. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.285247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frisbee JC, Samora JB, Peterson J, Bryner R. Exercise training blunts microvascular rarefaction in the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2483–H2492, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00566.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frisbee JC, Wu F, Goodwill AG, Butcher JT, Beard DA. Spatial heterogeneity in skeletal muscle microvascular blood flow distribution is increased in the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R975–R986, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00275.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwill AG, Frisbee SJ, Stapleton PA, James ME, Frisbee JC. Impact of chronic anticholesterol therapy on development of microvascular rarefaction in the metabolic syndrome. Microcirculation 16: 667–684, 2009. doi: 10.3109/10739680903133722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene AS, Lombard JH, Cowley AW Jr, Hansen-Smith FM. Microvessel changes in hypertension measured by Griffonia simplicifolia I lectin. Hypertension 15: 779–783, 1990. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.15.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutterman DD, Chabowski DS, Kadlec AO, Durand MJ, Freed JK, Ait-Aissa K, Beyer AM. The human microcirculation: regulation of flow and beyond. Circ Res 118: 157–172, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton WF, Moore JW, Kinsman JM, Spurling RG. Studies on the circulation. IV. Further analysis of the injection method, and of changes in hemodynamics under physiological and pathological conditions. Am J Physiol 99: 534–551, 1932. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1932.99.3.534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriksen EJ, Diamond-Stanic MK, Marchionne EM. Oxidative stress and the etiology of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 993–999, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keske MA, Premilovac D, Bradley EA, Dwyer RM, Richards SM, Rattigan S. Muscle microvascular blood flow responses in insulin resistance and ageing. J Physiol 594: 2223–2231, 2016. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.283549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunert MP, Liard JF, Abraham DJ, Lombard JH. Low-affinity hemoglobin increases tissue Po2 and decreases arteriolar diameter and flow in the rat cremaster muscle. Microvasc Res 52: 58–68, 1996. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1996.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loader J, Montero D, Lorenzen C, Watts R, Méziat C, Reboul C, Stewart S, Walther G. Acute hyperglycemia impairs vascular function in healthy and cardiometabolic diseased subjects: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 2060–2072, 2015. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machado MV, Martins RL, Borges J, Antunes BR, Estato V, Vieira AB, Tibiriçá E. Exercise training reverses structural microvascular rarefaction and improves endothelium-dependent microvascular reactivity in rats with diabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 14: 298–304, 2016. doi: 10.1089/met.2015.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nies AS. Prostaglandins and the control of the circulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 39: 481–488, 1986. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padilla DJ, McDonough P, Behnke BJ, Kano Y, Hageman KS, Musch TI, Poole DC. Effects of Type II diabetes on capillary hemodynamics in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2439–H2444, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00290.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenthal T, Younis F, Alter A. Combating combination of hypertension and diabetes in different rat models. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 3: 916–939, 2010. doi: 10.3390/ph3040916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiffrin EL. Mechanisms of remodelling of small arteries, antihypertensive therapy and the immune system in hypertension. Clin Invest Med 38: E394–E402, 2015. doi: 10.25011/cim.v38i6.26202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sebai M, Lu S, Xiang L, Hester RL. Improved functional vasodilation in obese Zucker rats following exercise training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1090–H1096, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00233.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tigno XT, Hansen BC, Nawang S, Shamekh R, Albano AM. Vasomotion becomes less random as diabetes progresses in monkeys. Microcirculation 18: 429–439, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tune JD, Goodwill AG, Sassoon DJ, Mather KJ. Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Transl Res 183: 57–70, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiang L, Dearman J, Abram SR, Carter C, Hester RL. Insulin resistance and impaired functional vasodilation in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1658–H1666, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01206.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]