Abstract

Neonatal asphyxia leads to cerebrovascular disease and neurological complications via a mechanism that may involve oxidative stress. Carbon monoxide (CO) is an antioxidant messenger produced via a heme oxygenase (HO)-catalyzed reaction. Cortical astrocytes are the major cells in the brain that express constitutive HO-2 isoform. We tested the hypothesis that CO, produced by astrocytes, has cerebroprotective properties during neonatal asphyxia. We developed a survival model of prolonged asphyxia in newborn pigs that combines insults of severe hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis while avoiding extreme hypotension and cerebral blood flow reduction. During the 60-min asphyxia, CO production by brain and astrocytes was continuously elevated. Excessive formation of reactive oxygen species during asphyxia/reventilation was potentiated by the HO inhibitor tin protoporphyrin, suggesting that endogenous CO has antioxidant effects. Cerebral vascular outcomes tested 24 and 48 h after asphyxia demonstrated the sustained impairment of cerebral vascular responses to astrocyte- and endothelium-specific vasodilators. Postasphyxia cerebral vascular dysfunction was aggravated in newborn pigs pretreated with tin protoporphyrin to inhibit brain HO/CO. The CO donor CO-releasing molecule-A1 (CORM-A1) reduced brain oxidative stress during asphyxia/reventilation and prevented postasphyxia cerebrovascular dysfunction. The antioxidant and antiapoptotic effects of HO/CO and CORM-A1 were confirmed in primary cultures of astrocytes from the neonatal pig brain exposed to glutamate excitotoxicity. Overall, prolonged neonatal asphyxia leads to neurovascular injury via an oxidative stress-mediated mechanism that is counteracted by an astrocyte-based constitutive antioxidant HO/CO system. We propose that gaseous CO or CO donors can be used as novel approaches for prevention of neonatal brain injury caused by prolonged asphyxia.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Asphyxia in newborn infants may lead to lifelong neurological disabilities. Using the model of prolonged asphyxia in newborn piglets, we propose novel antioxidant therapy based on systemic administration of low doses of a carbon monoxide donor that prevent loss of cerebral blood flow regulation and may improve the neurological outcome of asphyxia.

Keywords: astrocyte protection, carbon monoxide-releasing molecule-1, cerebral blood flow regulation, cerebral circulation newborn pigs, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal asphyxia is defined as the state producing a combination of systemic hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and metabolic acidosis that may occur before and during birth and the neonatal period (1, 15–18, 39). Compromised placental or pulmonary gas exchange in fetuses and neonates, as well as numerous maternal complications (low blood pressure, inadequate blood oxygenation, anesthesia, severe blood loss, sepsis, etc.), is among the factors that may lead to perinatal/neonatal asphyxia (1, 13, 14). Neonatal brain injury is the most recognized complication of asphyxia occurring in newborn infants. It frequently leads to hypoxia-ischemia encephalopathy (HIE) in survivors and an elevated risk of cerebral palsy, stroke, developmental delay, intellectual disabilities, mental retardation, and physical disabilities (7, 29, 42, 45, 46). Providing sufficient oxygenation, maintaining appropriate blood pressure, and implementing mild head/total body cooling are the only current treatment options for neonates with mild to moderate HIE (6, 9, 20, 22, 44).

Clearly, more studies in relevant large animal models of neonatal asphyxia are needed to explore the mechanism of neonatal brain injury caused by asphyxia and to propose novel mechanism-based therapeutic interventions to improve the neurological outcome in survivors. Asphyxia is frequently accompanied by a range of comorbidities, including severe hypotension, bradycardia, and cerebral ischemia, that contribute to the high mortality rate. Cerebral ischemia greatly contributes to brain injury caused by asphyxia. Many cases of asphyxia in newborns occur with less severe forms of cerebral ischemia. These conditions can be caused by cardiac arrest, head trauma, nuchal cord compression, suffocation, or certain respiratory conditions. We aimed at establishing a newborn pig survival model of prolonged asphyxia without comorbidities of severe hypotension and cerebral blood flow reduction.

Oxidative stress during asphyxia/reventilation is the key component in the mechanism of neonatal brain injury (34–37, 43). Excessive accumulation of the excitotoxic neurotransmitter glutamate has been identified as the major source of oxidative stress in the asphyxiated brain (6, 7, 10, 13, 15, 17, 43, 45, 46). The search for interventions based on enhancing the endogenous antioxidant defense mechanism appears to be a perspective approach to neuroprotection in asphyxiated newborns.

The neonatal brain has a potent endogenous cytoprotective system that includes carbon monoxide (CO), a gaseous messenger with antioxidant properties (25, 30). Brain CO is produced via the heme degradation reaction catalyzed by heme oxygenase (HO) that is constitutively expressed as the HO-2 isoform (25, 30). Astrocytes, which comprise >80% of brain cells, are the major CO-producing cells (33, 47). HO-2 of the neonatal brain is rapidly activated under the conditions of oxidative stress during neonatal epileptic seizures (8, 30). To date, the responses on the neonatal brain HO/CO system to asphyxia have not yet been investigated.

To investigate the contribution of HO/CO to the course and outcome of neonatal asphyxia, we developed a survival model of prolonged asphyxia in newborn pigs that combines the insults of severe hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis without comorbidity of severe hypotension and cerebral ischemia. Using this in vivo model, we tested the hypotheses that 1) asphyxia acutely increases brain CO production via HO-2 activation, 2) astrocytes are the major source of brain CO elevation during asphyxia, 3) astrocytic CO activation has antioxidant properties, 4) prolonged asphyxia causes sustained cerebral vascular dysfunction, and 5) treatment with the CO donor molecule CO-releasing molecule-A1 (CORM-A1) reduces brain oxidative stress and protects against cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by prolonged neonatal asphyxia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Newborn piglets (1–5 days old, 1.5–2.5 kg, either sex) were purchased from a commercial breeder. Veterinary care was provided by the Department of Comparative Medicine. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of animals in research. Every effort was made to ensure that any potential discomfort, distress, pain, and injury was minimized.

Model of neonatal asphyxia.

We propose a new model of prolonged (50–60 min) neonatal asphyxia and resuscitation with ambient air that produces high survival rates compared with the models of severe asphyxia previously developed in newborn pigs (34–37). Our new model of asphyxia combines hypoxia (arterial Po2: 30–40 mmHg) with hypercapnia (arterial Pco2: 70–80 mmHg) and acidosis (pH 6.9–7.1) without causing severe bradycardia, severe hypotension, and cerebral blood flow reduction. Importantly, this model allows investigation of the long-term outcome of asphyxia on cerebral vascular functions in survivors. Body temperature was maintained at 37–38°C by a servo-controlled heating pad. Asphyxia was induced by ventilating anesthetized intubated piglets with 8% CO2, 10% O2, and 82% N2 to obtain a goal arterial Po2 of 30–40 mmHg. A soft blood pressure cuff around the neck was inflated to 100 mmHg to mildly compress the carotid arteries and jugular veins. Mild compression of the neck during asphyxia allows avoidance of the cerebrovascular steal phenomenon, thus preventing severe hypotension, cardiovascular failure, and mortality. After 50–60 min of asphyxia, the ventilation gas was returned to room air, and the cuff was deflated. Sham control piglets were ventilated with room air throughout, and the neck cuff was not inflated.

The nonsurvival protocol of prolonged asphyxia was designed to characterize the changes in systemic and cerebrovascular parameters during 60 min of asphyxia and 60–120 min of reventilation. For nonsurvival experiments, piglets were initially anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (33:2.0 mg/kg im) and maintained on α-chloralose (50 mg/kg initially plus 5 mg/kg for maintenance as needed). Ketamine is a rapidly acting and short-lived analgesic and anesthetic compound. Although ketamine is an antagonist of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors, because of its short lifespan no reduction of cerebral vasodilator responses to N-methyl-d-aspartate or glutamate are observed, as tested by the cranial window technique 2–3 h after the injection. Anesthetized animals were instrumented with femoral catheters for measuring blood gases and systemic cardiovascular parameters. Closed cranial windows were installed to observe the changes in pial arteriolar diameters by intravital microscopy. We also collected the samples of periarachnoid corticospinal fluid (pCSF) from under the cranial window to determine the brain production of CO.

The survival protocol was designed to investigate the long-term outcome of prolonged asphyxia on cerebral vascular functions. For survival experiments, piglets were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (33:2.0 mg/kg im) without α-chloralose supplementation. In these experiments, the instrumentation of animals was kept minimal, and asphyxia was limited to 50 min to allow full long-term recovery. The experimental groups included 1) the normoxic sham control group (n = 6), 2) the 24-h postasphyxia group (n = 5), 3) the 48-h postasphyxia group (n = 5), 4) tin protoporphyrin (SnPP)-treated 48-h postasphyxia groups (n = 4), and 5) CORM-A1-treated 48-h postasphyxia groups (n = 6). SnPP (3 mg/kg ip) and CORM-A1 (2 mg/kg ip) were administered 30 min before asphyxia. When the piglets could stand and walk after recovery from asphyxia, they were returned to the animal facilities to recover for 24 or 48 h before postasphyxia cerebral vascular functions were investigated.

Intravital microscopy of pial arterioles.

The closed cranial window technique was used for the observation of pial arterioles and collection of pCSF during asphyxia/reventilation and for testing postasphyxia cerebral vascular functions. Animal instrumentation, cranial window placement, and pCSF collection have been previously described in detail (8, 19, 26, 27). Piglets were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (33:2.0 mg/kg im) supplemented by α-chloralose (50 mg/kg initially plus 5 mg/kg for maintenance as needed). Femoral arterial and venous catheters were inserted for monitoring of cardiovascular parameters and blood gases. Pial arteriolar diameter was measured with a videomicrometer coupled to a television camera mounted on the microscope. Two to three medium-sized pial arterioles (40–80 μm in diameter) were selected for observation in each piglet. pCSF was collected from under the cranial window for the detection of brain CO production before, during, and after asphyxia.

Cerebral vascular functions relevant to brain blood flow regulation were tested 24 and 48 h after asphyxia or sham control by responses of pial arterioles to physiologically relevant topical vasodilators (21, 24, 47) including 1) endothelium-dependent bradykinin (10−6 M), 2) astrocyte-dependent ADP (10−4 M), 3) endothelium- and astrocyte-dependent glutamate (10−5 M), and 4) vascular smooth muscle-targeting vasodilator nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside (10−6 M) and the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol (10−6 M), which cause vascular smooth muscle dilation via cGMP- and cAMP-mediated mechanisms, respectively, independently of endothelial or astrocytic influences. We also evaluated cerebral vasodilation to hypercapnia, a paramount physiological regulator of the cerebral circulation that requires intact endothelial influences (23). Hypercapnia (arterial Pco2: ∼80 mmHg, arterial Po2: ∼90 mmHg, pH ∼7.0) was produced by ventilation with an elevated CO2 gas mixture (10% CO2, 20% O2, and 70% N2). By determining the effects of asphyxia on pial arteriolar responses to these cell-specific test stimuli, we could evaluate in vivo whether the cerebral vascular dysfunction is due to injury to endothelium, astrocytes, or vascular smooth muscle.

Detection of cerebral blood flow.

The PeriFlux System 4001 laser-Doppler flowmeter (Perimed) was used to measure relative cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV), as we have previously described (11). To insert the probe, a 2-mm hole was drilled in the left parietal section of the skull close to the sagittal suture. For CBFV measurements, the sensor tip of the Doppler flowmeter was placed in direct contact with the dura mater and secured with bone wax and dental acrylic. Relative CBFV reflects a net particle flow within a 1-mm3 cube at the sensor tip and is expressed as perfusion units (PU). The values of relative CBFV were compared in each animal before, during, and after asphyxia (n = 5 animals).

Freshly isolated brain cortex astrocytes were obtained from the cerebral cortex for in vivo detection of ROS, CO concentration, and HO-1/HO-2 expression in control and asphyxic brains. The brain cortex homogenate was filtered through 300-, 60-, and 20-µm mesh nylon filters, as we have previously described (33, 47). Cerebral vessels (300–60 µm) were collected on the 60-µm filter, whereas brain capillaries and neurons were largely retained by the 20-µm filter. The 20-µm filtrate was composed mainly of astrocytes identified by the astrocyte-specific markers glial fibrillary acidic protein and aquaporin-4 (33).

Primary astrocyte cultures.

Isolated cortical astrocytes were plated in astrocyte-supporting media (DMEM with 10 ng/ml EGF and 20% FBS) to 75-ml Costar flasks and grown for 10–14 days to confluence, as previously described elsewhere (33). For the experiments involving detection of CO production, confluent astrocytes were replated to Cytodex-3 collagen-coated dextran-matrix beads (GE Healthcare, 105 cells/ml beads) and cultured in Chemglass Life Sciences Spinner flasks (Fisher Scientific) with continuous stirring (20 rpm) for 4–7 days until confluence (33). Astrocyte-covered beds were transferred to leak-proof vessels for further detection of CO levels in the head space by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. For the experiments involving detection of ROS and apoptosis, astrocytes were plated to 12-well Costar plates and grown to confluence for 4–5 days. All experiments were conducted in confluent quiescent cells.

ROS production was detected using the brain-permeable, oxidant-sensitive probe dihydroethidium (DHE), as previously described elsewhere (31). DHE is oxidized primarily by superoxide anion to a red fluorescent dye, ethidium, and intercalates with nuclear DNA. DHE (2 mg/kg iv) was administered to control normoxic piglets or 1-h postasphyxia piglets 30 min before the brain cortex was extracted. To detect the effects of asphyxia on in vivo astrocyte ROS production, freshly isolated cortical astrocytes were obtained from the normoxic control group (n = 7) and from asphyxia groups with an intact or modulated HO/CO system: 1) intact HO (n = 4), 2) inhibited HO (HO inhibitor SnPP, 3 mg/kg ip 30 min before asphyxia, n = 4), 3) CORM-A1 (2 mg/kg ip 30 min before asphyxia, n = 4), and 4) bilirubin (5 mg/kg ip 30 min before asphyxia, n = 4). In astrocyte cultures exposed to asphyxia-related prooxidants glutamate and TNF-α, ROS production was detected using DHE labeling, as previously described (31). Ethidium fluorescence was measured by the Synergy HT microplate reader and normalized to the amount of astrocyte protein.

Detection of CO by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry.

For in vivo detection of CO levels in the cerebral circulation in newborn pigs, samples of pCSF (0.4 ml) were collected from the brain surface underneath the cranial window at 10-min intervals during the 2.5-h experimentation period that included basal normoxia conditions, asphyxia, and reventilation. To detect in vivo astrocytic CO production during normoxic, asphyxic, and reventilation periods, cortical astrocytes were freshly isolated from the brains of normoxic and 1-h asphyxic animals. Samples of pCSF, freshly isolated cortical astrocytes, or astrocytes cultured on Cytodex beads were placed in Thermo Scientific 9-mm leak-proof vessels, sealed with tight rubber seals, and incubated with Krebs solution for 1 h at 37°C. The 13C18O standard was added to all samples for the purpose of CO quantification. The concentration of CO in the headspace gas was detected based on the peak areas corresponding to 12C16O and 13C18O using an Agilent 5975 GC/MSD ChemStation (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and normalized to the protein amount in the samples, as previously described in detail elsewhere (26, 48).

Apoptosis detection by DNA fragmentation.

Quiescent cortical astrocytes in primary cultures were exposed to the prooxidants glutamate (1 mM) or human TNF-α (10 ng/ml) in glutamine-free DMEM-0% FBS for 3 h at 37°C. Apoptotic cytoplasmic DNA fragments were immunodetected by an ELISA kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and visualized with 2,2′-azino-di(3-ethylbenzthiazolin-sulfonate), as previously described (2, 3). Absorbance at 405 nm was measured by a Synergy HT microplate reader and normalized to the protein amount detected by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

HO-2/HO-1 detection.

Freshly isolated cortical astrocytes from control normoxic and postasphyxic piglets (5-, 24-, and 48-h recovery) were lysed in the Laemmli sample buffer, separated by 9% SDS-PAGE (50 µg/lane), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, as previously described elsewhere (8, 32). Membranes were probed with polyclonal anti-human HO-2 (SPA 897, 1:5,000 dilution, StressGen Biotechnologies, Victoria, BC, Canada) or polyclonal anti-human HO-1 (SPA 895, 1:5,000 dilution, StressGen) followed by peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000 dilution, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). As positive controls, we used recombinant rat HO-1 and human HO-2 proteins (StressGen). For quantification purposes, membranes were reprobed with monoclonal antibodies against actin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) followed by peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch). Bands were visualized with Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) and quantified by digital densitometry using National Institutes of Health Image 1.47v software.

Statistical analysis.

Values are presented as means ± SE of absolute values or percentages of control. Proper sample sizes were calculated for a power of 0.8 in all tests. Data were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA. A level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Materials.

Cell culture reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD), Hyclone (South Logan, UT), Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN), and GE Healthcare Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). SnPP was purchased from Frontier Scientific (Logan, UT). DHE was from Invitrogen (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). CORM-A1 was from Dalton Pharma Services (Toronto, ON, Canada). All other reagents were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

Arterial and sagittal sinus blood gases.

Asphyxia caused by ventilating piglets with 8% CO2-10% O2 produced immediate changes in arterial blood gases that were sustained for the duration of the 60-min experimental period (n = 8; Table 1). During the control normoxia period, arterial blood gases were as follows: arterial Po2 104 ± 4 mmHg, arterial Pco2 36 ± 2 mmHg, and pH 7.40 ± 0.03. During the asphyxia period, we observed a dramatic reduction in blood oxygenation (arterial Po2: 37 ± 4 mmHg) that was accompanied by increased arterial Pco2 (76 ± 3 mmHg) and acidosis (pH 7.05 ± 0.02). Cortical tissue oxygenation, as evaluated by sagittal sinus gases, was also dramatically reduced (sagittal sinus blood Po2: 13 ± 2 mmHg) compared with normoxic values (Table 1). It was accompanied by increased sagittal sinus blood Pco2 (84 ± 6 mmHg) and acidification in the cortical tissue (pH 7.1 ± 0.1). Postasphyxia reventilation with room air completely restored arterial blood oxygenation within 10 min, whereas normalization of arterial Pco2 (39 ± 3 mmHg) and pH was achieved within 60 min of reventilation. Sagittal blood gases returned to the normoxic level after 60-min reventilation.

Table 1.

Changes in systemic and cerebrovascular parameters during prolonged neonatal asphyxia

| Asphyxia, min |

Reventilation, min |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Normoxia (Control) | 10 | 30 | 60 | 10 | 60 |

| Arterial Po2, mmHg | 104 ± 4 | 37 ± 4* | 36 ± 3* | 36 ± 4* | 89 ± 6 | 89 ± 7 |

| Arterial Pco2, mmHg | 36 ± 2 | 76 ± 3* | 72 ± 3* | 76 ± 3* | 47 ± 5* | 39 ± 3 |

| Arterial pH | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1* | 7.0 ± 0.1* | 7.0 ± 0.1* | 7.2 ± 0.1* | 7.3 ± 0.1 |

| Sagittal sinus blood Po2, mmHg | 19 ± 2 | ND | 13 ± 2* | 12 ± 3* | 17 ± 2* | 19 ± 1 |

| Sagittal sinus blood Pco2, mmHg | 51 ± 3 | ND | 81 ± 5* | 84 ± 6* | 61 ± 2* | 51 ± 2 |

| Sagittal pH | 7.4 ± 0.1 | ND | 7.1 ± 0.1* | 7.1 ± 0.1* | 7.2 ± 0.1* | 7.3 ± 0.1* |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mmHg | 67 ± 6 | 39 ± 9* | 37 ± 3* | 36 ± 3* | 50 ± 5* | 49 ± 5* |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 179 ± 18 | 166 ± 11 | 162 ± 14 | 162 ± 15 | 173 ± 13 | 169 ± 19 |

| Pial arteriolar diameter, %normoxia | 100 | 139 ± 5* | 133 ± 8* | 123 ± 14* | 113 ± 8 | 105 ± 6 |

| Cerebral blood flow velocity, perfusion units | 131 ± 20 | ND | 137 ± 17 | 118 ± 7 | ND | 123 ± 7 |

Values are means ± SE for each time point; n = 8 piglets. Asphyxia was produced by ventilation with 8% CO2, 10% O2, and 82% N2 for 60 min. Room air was used for ventilating newborn piglets before and after asphyxia. Blood gases in arterial blood (arterial Po2 and arterial Pco2) and sagittal sinus blood (sagittal sinus blood Po2 and Pco2), mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, pial arteriolar diameter, and cerebral blood flow velocity were measured before, during, and after 60-min asphyxia. ND, not detected.

P < 0.05 compared with normoxic levels.

Effects of asphyxia on systemic cardiovascular parameters, diameter of pial arterioles, and cerebral blood flow.

Severe hypotension is a serious complication of asphyxia that may lead to cardiac arrest and death. In newborn pigs without the neck cuff (n = 4), asphyxia caused severe hypotension and bradycardia. In these piglets, mean arterial blood pressure was reduced from 64 ± 7 (normoxia) to 30 ± 2 mmHg (asphyxia), whereas heart rate was reduced from 140 ± 14 (normoxia) to 105 ± 10 (asphyxia) beats/min. In newborn pigs equipped with inflated neck cuff (100 mmHg), asphyxia caused only moderate systemic hypotension (38 ± 3 mmHg) that was not accompanied by a heart rate reduction (Table 1). These findings suggest that placing moderately inflated neck cuff prevents extreme hypotension and bradycardia during asphyxia, thus preserving cardiovascular function.

Asphyxia caused immediate and sustained vasodilation of pial arterioles (20–40% above the normoxia diameter) that returned to the baseline level during reventilation (Table 1). Relative CBFV as measured by laser-Doppler flowmetry measured in perfusion units was maintained relatively constant during asphyxia and reventilation (Table 1). During asphyxia, the incidence of no flow and backward flow was rare or none. Overall, the proposed model of prolonged asphyxia is not accompanied by cerebral ischemia, and extreme changes in cerebral perfusion during asphyxia and reventilation periods are avoided.

In vivo CO production is increased during asphyxia.

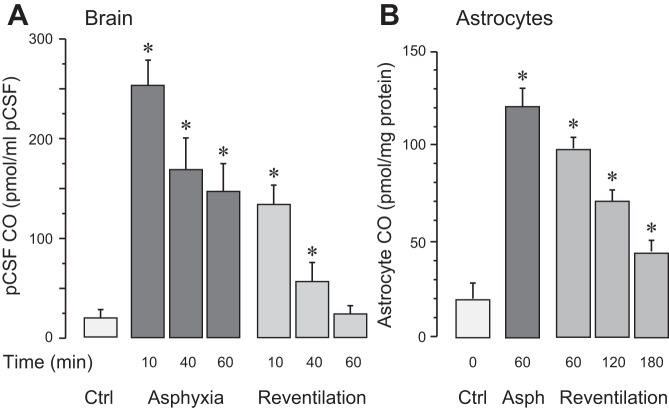

Overall brain CO production was evaluated by the levels of CO in samples of pCSF collected from under the cranial window at 10-min intervals before, during, and after asphyxia (Fig. 1A). During normoxia, pCSF CO concentration was 20 ± 5 pmol CO/ml pCSF. Asphyxia produced an immediate ∼10-fold increase in CO levels that was sustained throughout the 60-min period (n = 6; Fig. 1A). During 60 min of reventilation with ambient air, pCSF CO values gradually returned to the baseline level (Fig. 1A). In vivo astrocyte CO production was detected in cortical astrocytes freshly isolated from the brain during normoxia, after 60 min of asphyxia, and after 60, 120, and 180 min of reventilation (n = 15 piglets). During control normoxic conditions, the astrocytic CO level was 18 ± 6 pmol CO/mg protein. After 60 min of asphyxia, the astrocyte CO level was elevated six- to eightfold above the normoxic level (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B). During the reventilation period, astrocytic CO production gradually decreased but remained elevated even after 3 h of reventilation (45 ± 16 pmol CO/mg protein, P < 0.05 compared with normoxia values; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

In vivo carbon monoxide (CO) production by the brain and astrocytes during asphyxia and reventilation. A: overall brain CO production was evaluated by CO levels in the cortical periarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid (pCSF). pCSF samples were collected under normoxic conditions (Ctrl) and during asphyxia (10–60 min) and reventilation with air (10–60 min); n = 6 piglets. B: in vivo CO production by freshly isolated cortical astrocytes under control (Ctrl) normoxia conditions, after 60 min of asphyxia, and after 60, 120, and 180 min of reventilation with air; n = 6 piglets. Values are means ± SE for each time point. *P < 0.05 compared with control normoxic levels.

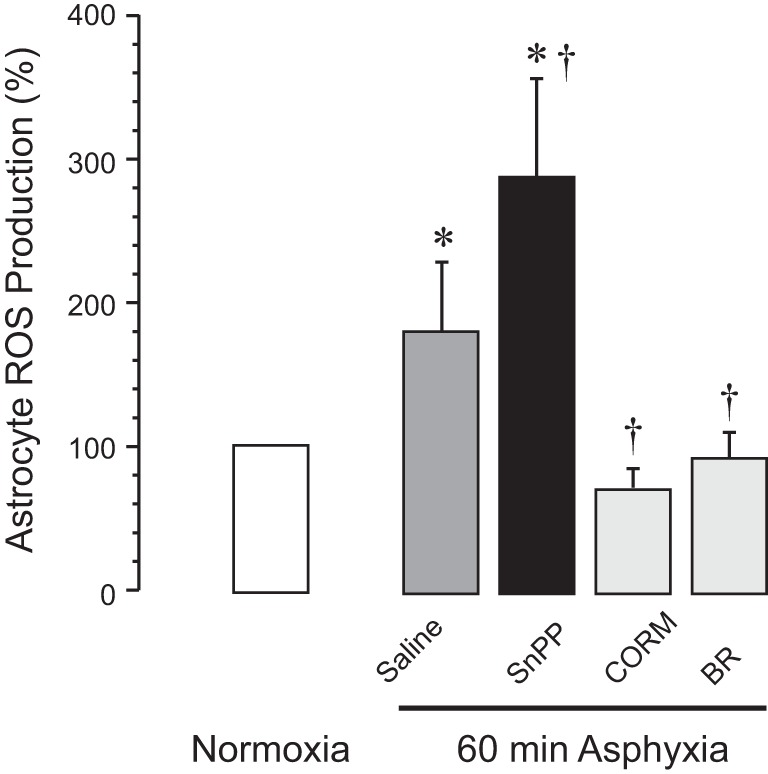

In vivo astrocyte ROS production is increased during asphyxia in a HO/CO-dependent manner.

In vivo ROS production was detected in cortical astrocytes freshly isolated from DHE-labeled normoxic and asphyxic brains (Fig. 2). Astrocyte ROS production increased approximately twofold after 60-min asphyxia, suggesting that cortical astrocytes are the source of brain oxidative stress. The HO inhibitor SnPP (30 mg/kg ip) administered 30 min before asphyxia greatly exacerbated astrocytic ROS production in the asphyxic brain. In contrast, the surge of astrocyte-produced ROS during asphyxia was completely prevented when piglets were treated with the products of HO activity CO (as CORM-A1, 2 mg/kg ip) or bilirubin (5 mg/kg ip) administered 30 min before asphyxia.

Fig. 2.

In vivo astrocyte production of ROS is increased during asphyxia. Astrocyte ROS levels were detected using in vivo brain labeling with dihydroethidium. Cortical astrocytes were isolated from the normoxic group (n = 7) or from 60-min asphyxia groups: 1) intact heme oxygenase (HO) activity (saline control, n = 4), 2) inhibited HO activity [tin protoporphyrin (SnPP), 3 mg/kg ip, 30 min before asphyxia, n = 4], 3) carbon monoxide-releasing molecule-A1 (CORM; 2 mg/kg ip, 30 min before asphyxia, n = 4), and 4) bilirubin (BR; 5 mg/kg ip, 30 min before asphyxia, n = 4). Values are means ± SE for each time point. *P < 0.05 compared with the normoxic group; †P < 0.05 compared with the intact HO activity (saline control) asphyxia group.

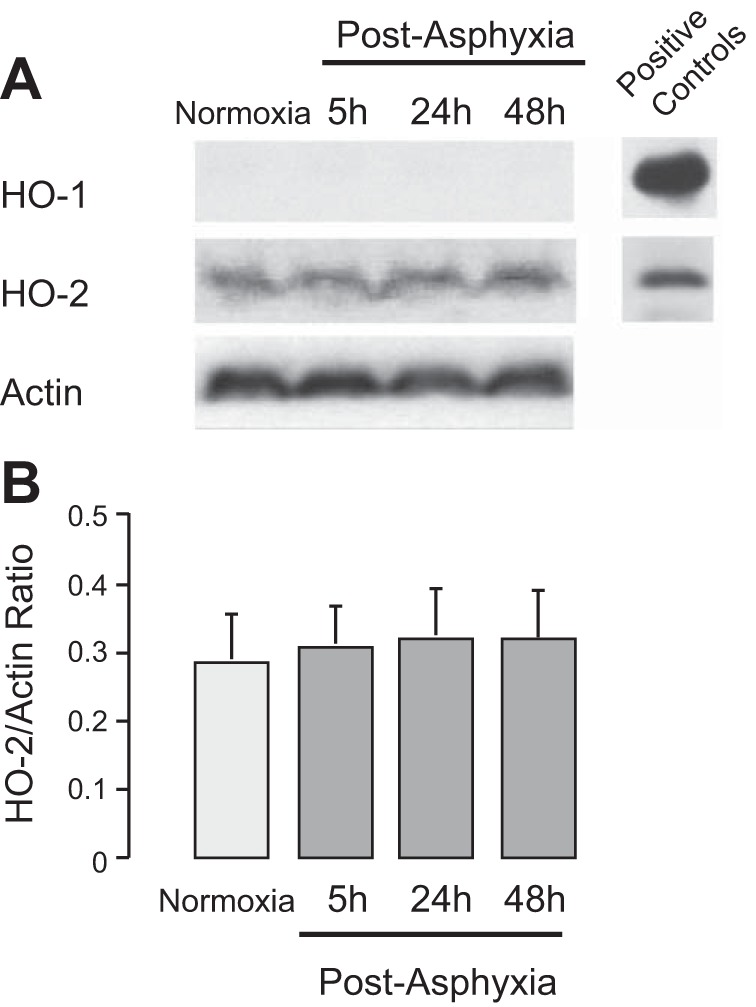

Asphyxia does not upregulate astrocyte HO-1/HO-2 proteins.

Increased astrocyte CO production during asphyxia can be caused by upregulated HO expression in cortical astrocytes. We compared HO-1 and HO-2 protein expression in cortical astrocytes freshly isolated from the cerebral cortex of normoxic and postasphyxia piglets (5, 24, and 48 h after asphyxia; Fig. 3). Inducible HO-1 was not expressed in the normoxic newborn pig brain, supporting our previous reports (8, 30), and was not upregulated during the 5- to 48-h postasphyxia recovery period. Constitutive HO-2 was highly expressed in astrocytes from the control normoxic newborn pig brain. Astrocyte HO-2 expression was not increased during the 5−48 h of the postasphyxia period (Fig. 3). These data suggest that the acute increase in astrocytic CO production during asphyxia may involve posttranslational activation of constitutive HO-2.

Fig. 3.

Expression of heme oxygenase (HO)-1 and HO-2 proteins in cortical astrocytes. Freshly isolated cortical astrocytes were collected from normoxic piglets and postasphyxia piglets (5, 24, and 48 h of reventilation). HO-1/HO-2 proteins were detected using HO isoform-selective antibodies and normalized to the housekeeping gene (actin) expression. Positive controls: HO-1 and HO-2 recombinant proteins. A: representative immunoblot analysis for HO-1 and HO-2. B: HO-2-to-actin ratio (units). n = 3 piglets in each group.

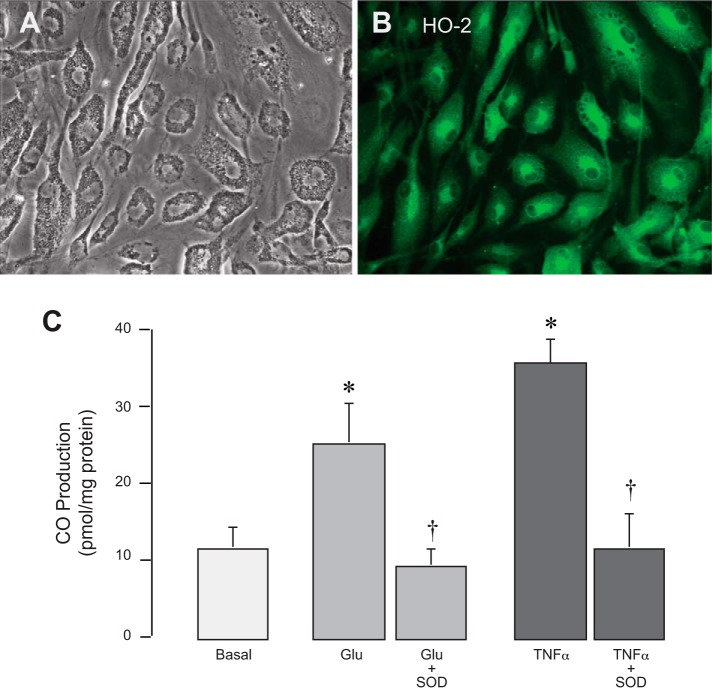

CO production by cultured astrocytes is increased by oxidative stress.

HO-2 is highly expressed in cultured cortical astrocytes (Fig. 4, A and B) and is the source of CO production (Fig. 4C). We investigated whether astrocytic HO-2 is activated during oxidative stress. The prooxidants glutamate (1 mM) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml) rapidly (1 h) increased astrocytic CO production two- to threefold above baseline (Fig. 4C). The increase in CO production in response to glutamate and TNF-α was completely abrogated by a potent antioxidant, SOD (1,000 U/ml). These data suggest that HO-2 activity is regulated via an oxidant-sensitive posttranslational mechanism.

Fig. 4.

Astrocytic heme oxygenase (HO)-2 is acutely activated by oxidative stress. Cortical astrocytes from newborn piglets in primary cultures (phase contrast; A) expressed HO-2 (immunofluorescence; B) and produced carbon monoxide (CO; C). Astrocytic CO production was detected after 1 h of exposure to the prooxidants glutamate (Glu; 1 mM) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of the antioxidant SOD (1,000 U/ml; C). n = 4 independent cultures. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding basal values; †P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding prooxidants.

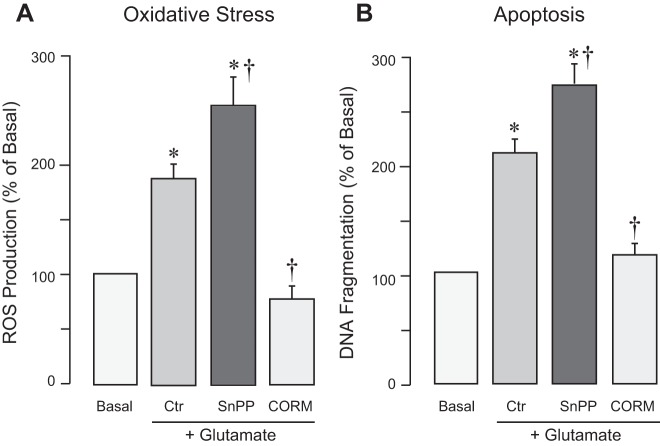

Astrocytic CO has antioxidant and cytoprotective effects during oxidative stress injury.

Asphyxia-related oxidative stress was modeled in vitro by exposing astrocytes to excitotoxic glutamate. In primary cultured cortical astrocytes, glutamate (2 mM, 1 h) increased ROS production (Fig. 5A) and caused apoptosis detected by DNA fragmentation (Fig. 5B). When astrocyte CO production was inhibited by the HO inhibitor SnPP, the prooxidant and proapoptotic effects of glutamate were exacerbated (Fig. 5, A and B). CO released from the donor molecule CORM-A1 (50 µM) completely blocked the oxidative stress and apoptosis induced in astrocytes exposed to glutamate excitotoxicity (Fig. 5, A and B). These data indicate that CO endogenously produced by astrocytes or released from the CO donor molecule have antioxidant and cytoprotective effects.

Fig. 5.

Endogenous carbon monoxide (CO) and the CO donor CO-releasing molecule-A1 (CORM) prevent oxidative stress and apoptosis of astrocytes during excitotoxicity. ROS production (A) and DNA fragmentation (B) were detected in primary cortical astrocytes with 1) intact HO activity and 2) inhibited heme oxygenase (HO) activity [tin protoporphyrin (SnPP); 20 µM] and in astrocytes treated with the CO donor CORM-A1 (50 µM). Astrocytes were exposed to glutamate (2 mM). n = 4 independent cultures. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding baseline values; †P < 0.05 compared with the effects of glutamate in astrocytes with intact HO activity (Ctr).

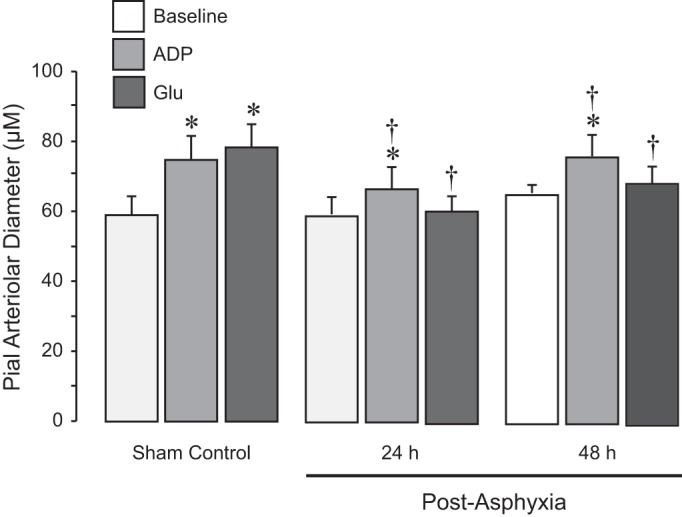

Impairment of cerebral vascular dilator functions after prolonged neonatal asphyxia.

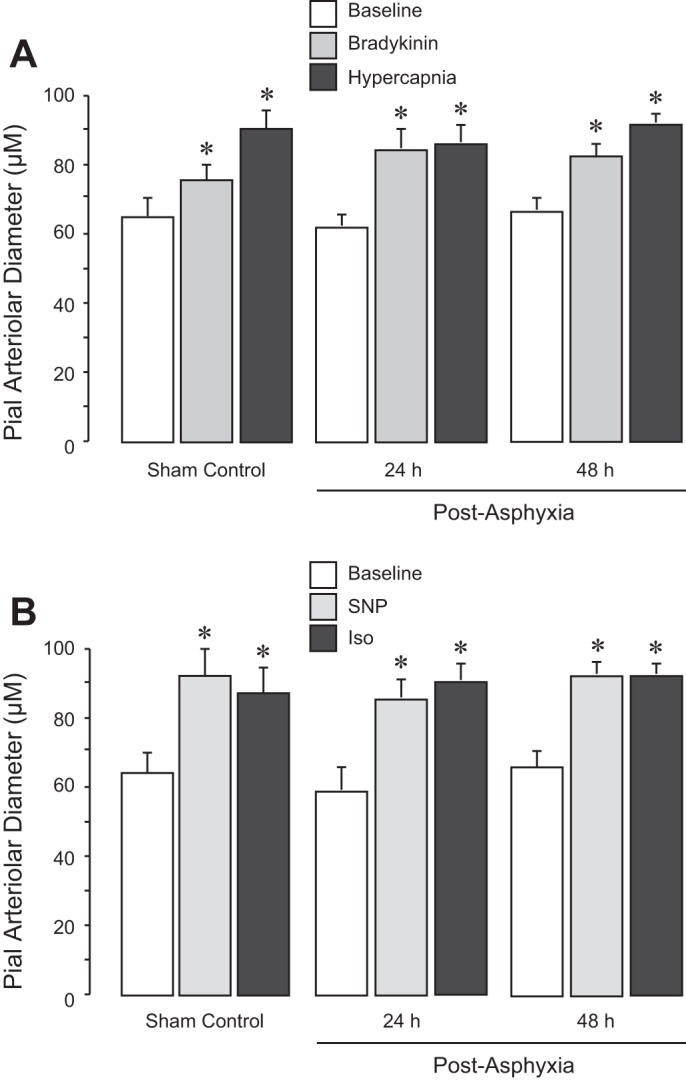

Cerebral vascular functions were tested 24 and 48 h after 50-min asphyxia by responses of pial arterioles to cell-specific vasodilators. Astrocyte-dependent cerebral vascular functions were tested by the responses of pial arterioles to topical ADP and to glutamate that requires both astrocytic and endothelial influences (Fig. 6). In the sham control normoxic group, pial arteriolar dilation to topical ADP (10−4 M) and glutamate (10−6 M) was ∼30% over the baseline diameter. In contrast, in both 24 and 48 h postasphyxia groups, vasodilator responses to ADP were reduced, and the responses to glutamate were severely compromised (Fig. 6). Endothelium-dependent cerebral vascular functions tested by responses of pial arterioles to topical bradykinin (10−7 M) and systemic hypercapnia (arterial Pco2: ∼80 mmHg, pH ∼7.0) were not impaired 24 and 48 h after asphyxia compared with the sham control group (Fig. 7). Generalized vascular smooth muscle function was not affected by asphyxia, as detected by vasodilator responses to SNP (10−6 M) and isoproterenol (10−6 M) that remained well preserved 24 and 48 h after asphyxia (Fig. 7). Overall, prolonged asphyxia caused sustained impairment of cerebral vascular responses to selected astrocyte- and endothelium-specific vasodilators.

Fig. 6.

Astrocyte-dependent cerebrovascular dilator functions detected 24 and 48 h after neonatal asphyxia. Prolonged asphyxia (50 min) was produced by ventilation with 8% CO2, 10% O2, and 82% N2. Reventilation was performed with ambient air. After 24- and 48-h recovery, pial arteriolar responses to the astrocyte-dependent topical vasodilator ADP (10−4 M) and to the astrocyte- and endothelium-dependent vasodilator glutamate (10−5 M) were tested in normoxic control (n = 6), 24-h postasphyxia (n = 5), and 48-h postasphyxia groups (n = 5). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding baseline diameters in each group; †P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding dilator responses in the sham control group.

Fig. 7.

Endothelium-dependent (A) and vascular smooth muscle-dependent (B) cerebrovascular dilator functions detected 24 and 48 h after neonatal asphyxia. Prolonged asphyxia (50 min) was produced by ventilation with 8% CO2, 10% O2, and 82% N2. Reventilation was performed with ambient air. After 24 and 48 h of recovery, the responses of pial arteriolar responses to the endothelium-dependent vasodilators bradykinin (10−6 M) and hypercapnia (arterial Pco2: ∼80 mmHg, pH ∼7.0; A) and to the smooth muscle-targeting vasodilators sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10−6 M) and isoproterenol (Iso; 10−6 M; B) were tested in normoxic control (n = 6), 24-h postasphyxia (n = 5), and 48-h postasphyxia groups (n = 5). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding baseline diameters in each group.

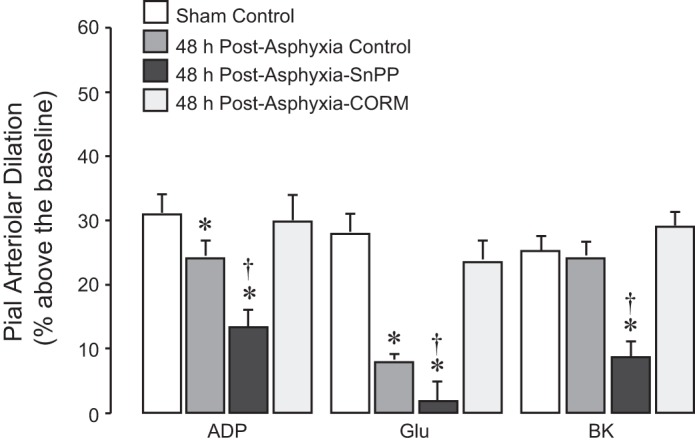

Effects of HO/CO inhibition and CORM-A1 therapy on cerebral vascular dysfunction caused by asphyxia.

To investigate the contribution of endogenous HO/CO to cerebral vascular outcome of asphyxia, piglets were pretreated with the HO inhibitor SnPP (3 mg/kg ip) 30 min before 50-min asphyxia (n = 4). To explore potential cerebroprotective effects of CO therapy against asphyxia-induced cerebral vascular dysfunction, CORM-A1 (2 mg/kg ip) was administered 30 min before 50-min asphyxia (n = 6). The intact control HO/CO piglets were untreated before asphyxia (n = 6). We compared 48 h postasphyxia cerebral vascular responses in the intact control HO/CO group and in SnPP- and CORM-A1-treated groups (Fig. 8). In the SnPP-inhibited HO/CO group, we observed a greater impairment of vasodilator responses to ADP and glutamate compared with the intact HO/CO group. Furthermore, postasphyxia responses to bradykinin were dramatically reduced in SnPP-treated newborn pigs but not in pigs from the postasphyxia intact HO/CO group. Remarkably, CORM-A1 completely prevented the reduction of cerebral vascular responses to ADP and glutamate caused by asphyxia. Postasphyxia dilator responses to hypercapnia, SNP, or isoproterenol were not reduced in HO/CO-intact, SnPP-inhibited, or CORM-A1-treated groups compared with the control normoxia group (data not shown). These findings demonstrate the importance of the HO/CO system as a cytoprotection mechanism against asphyxia-induced cerebral vascular dysfunction.

Fig. 8.

Influence of heme oxygenase (HO)/carbon monoxide (CO) modulators on cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by prolonged neonatal asphyxia. Newborn pigs were untreated (intact control HO/CO) or pretreated with the HO inhibitor tin protoporphyrin (SnPP; 3 mg/kg ip) or with CO-releasing molecule-A1 (CORM-A1; 2 mg/kg ip) 30 min before asphyxia. Prolonged asphyxia (50 min, arterial Po2: 36 ± 3 mmHg, arterial Pco2: 70 ± 3 mmHg, pH 7.0 ± 0.1) was produced by ventilation with 8% CO2, 10% O2, and 82% N2. Reventilation was performed with ambient air. After 48 h of recovery, pial arteriolar responses to topical ADP (10−4 M), glutamate (Glu; 10−5 M), and bradykinin (BK; 10−6 M) were tested in the 1) sham control normoxic group (n = 8), 2) intact HO/CO control postasphyxia group (n = 6), 3) SnPP-pretreated postasphyxia group (n = 4), and 4) CORM-A1-pretreated postasphyxia group (n = 6). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding dilator responses in sham control group; †P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding dilator responses in the intact control HO/CO group.

DISCUSSION

Cerebrovascular protection is an essential component in preventing neurodevelopmental complications frequently caused by asphyxia in newborn babies. We used a new survival model of prolonged asphyxia in newborn pigs to search for novel approaches to cerebrovascular protection. Prolonged neonatal asphyxia without cerebral ischemia leads to sustained impairment of cerebral vascular responses to selected astrocyte- and endothelium-dependent vasodilators. Our major novel finding is that cortical astrocytes respond to asphyxia-induced oxidative stress by activating the oxidant-sensitive constitutive HO-2 and increasing the production of the antioxidant cytoprotective messenger CO. ROS elevated in the asphyxic brain have dual functions as potent inducers of the neurovascular cell death and triggers of cell survival via the upregulated HO/CO system. Increased brain CO produced by astrocytes or released from the systemically administered donor molecule CORM-A1 prevents long-term cerebral vascular dysfunction caused by neonatal asphyxia.

Asphyxia in newborn infants causes cerebrovascular disease and neonatal brain injury and may lead to lifelong neurodevelopmental disabilities. However, numerous comorbidities of asphyxia, including severe hypotension, bradycardia, and cerebral ischemia, complicate dissecting the mechanism of cerebrovascular disease caused by asphyxia. We developed a survival model of prolonged asphyxia in newborn pigs without comorbidity of cerebral ischemia. This is a novel modification of hypoxic-ischemic insults to the fetal/neonatal brain (22, 34–37, 43) that combines insults of severe hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis while avoiding extreme systemic hypotension and reduction of cerebral blood flow. For asphyxia resuscitation, we used room air instead of 100% oxygen, as ambient air is more beneficial for newborn infants with asphyxia insult (41). Of importance is that our piglets survived 2 days postasphyxia without extraordinary care.

Using this model, we have demonstrated that prolonged neonatal asphyxia that is not accompanied by cerebral ischemia leads to prolonged cell-specific cerebral vascular dysfunction lasting for ≥48 h after resuscitation. The responses of pial arterioles to vasodilators that directly affect vascular smooth muscle (SNP and isoproterenol) were not affected by asphyxia. Pial arteriolar dilator responses to hypercapnia, a potent physiological regulator of cerebral blood flow, and to topical bradykinin, an endothelium-dependent vasodilator, were also not adversely affected by asphyxia. In contrast, vasodilator responses to the topically applied astrocyte-mediated vasodilator ADP were reduced 24 and 48 h after asphyxia. Most strikingly, the vasodilator responses to glutamate that require both astrocyte- and endothelium-dependent influences were severely compromised 24 and 48 h after prolonged asphyxia. We conclude that cerebral blood flow dysregulation during the delayed postasphyxia period involves cell-specific injury to the components of the neurovascular unit, including astrocytes and, to a lesser extent, endothelium, whereas cerebral vascular smooth muscle is largely spared from the injury.

Brain oxidative stress is an important contributor to cerebrovascular and neurological complications of neonatal asphyxia. In our previous studies, we have shown increased production of brain ROS in the model of acute severe asphyxia in newborn pigs (35, 36). An increase in lipid peroxidation products was observed in the brain after severe global hypoxia (43). In the present study, we have observed an increased ROS formation in the model of prolonged neonatal asphyxia without comorbidity of cerebral ischemia. Most importantly, we found that cortical astrocytes are a major source of increased brain ROS production during asphyxia/reventilation.

Enhancing endogenous antioxidant mechanisms in the brain appears to be a promising approach to prevention of neonatal brain injury. The main focus of our study is on an endogenous antioxidant defense mechanism in the brain that may protect it from severe cerebrovascular dysfunction. The brain has a potent antioxidant system based on the gaseous messenger CO produced in a HO-catalyzed reaction (25, 30). In the neonatal brain, constitutive HO-2 is highly expressed in the neurovascular unit, including endothelial cells and astrocytes, whereas inducible HO-1 is not detectable (8, 30–33). Brain HO-2 can be acutely activated via a posttranslational mechanism during epileptic seizures, leading to an elevation of brain CO production (8). We now report that asphyxia causes a surge of brain CO production due to activation of the astrocytic HO/CO system.

What is the mechanism by which astrocyte CO production is acutely increased during asphyxia? Cortical astrocytes from the newborn pig brain demonstrate a high expression of constitutive HO-2 while lacking HO-1 during the normoxia condition. We found no acute or long-term upregulation of astrocyte HO-1/HO-2 protein expression in the asphyxic neonatal brain. Our in vivo observations indicate the correlation between brain ROS and astrocyte CO dynamics during asphyxia and reventilation. We hypothesized that astrocyte HO-2 is an oxidant-sensitive enzyme that is acutely activated by oxidative stress. We tested this hypothesis in primary cultures of cortical astrocytes from the newborn pig brain that highly express constitutive HO-2. Astrocytes exposed to the asphyxia-related prooxidants glutamate and TNF-α by acutely increasing CO production. Remarkably, the elevation in CO production in response to these prooxidants was completely prevented by the antioxidant SOD. These data indicate that astrocyte HO-2 is an oxidant-sensitive enzyme that is acutely activated by oxidative stress and accounts an increased brain CO production during asphyxia.

The antioxidant and cytoprotective effects of the endogenous HO/CO system were tested in the model of astrocyte injury by excitotoxicity. Cortical astrocytes express ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) (33) and are targets for glutamate, a major prooxidant factor during asphyxia. Glutamate at excitotoxic concentrations, acting via iGluRs, causes oxidative stress and initiates astrocyte death by apoptosis. To determine the effects of endogenously produced CO, we pharmacologically blocked HO-2 activity with the HO inhibitor SnPP. In HO-inhibited cells, glutamate-stimulated ROS production and apoptosis were exacerbated, suggesting that endogenous CO has antioxidant and cytoprotective properties during excitotoxicity and asphyxia. To circumvent a potential impact of reduced clearance of prooxidant heme due to HO inhibition, we used a complementary model of HO activation using a CO donor. When astrocytes were treated with CORM-A1, glutamate was no longer able to increase ROS or cell death.

We tested in vivo the hypothesis that brain CO elevation due to activation of the astrocytic HO/CO or produced by exogenous CO donors improves the cerebrovascular outcome of prolonged neonatal asphyxia. When endogenous brain/astrocytic CO was reduced by the HO inhibitor SnPP, brain oxidative stress during asphyxia and the postasphyxia cerebral vascular dysfunction were greatly exacerbated. As we have previously demonstrated, CORM-A1, systemically administered to newborn pigs, increased the CO level in the brain (26, 48), reduced brain oxidative stress during epileptic seizures, and prevented seizure-induced sustained cerebrovascular injury in newborn pigs (26, 27, 31, 48). We now present evidence that CO/CORM-A1 therapy reduced brain oxidative stress and completely prevented long-term cerebral vascular dysfunction caused by prolonged neonatal asphyxia.

What is the mechanism of antioxidant effects of CO? The biological effects of CO are caused by its high-affinity binding to heme. At high concentrations (>1,000 ppm), CO produces systemic and cellular toxic effects primary to binding to hemoglobin, leading to hypoxic brain injury and even death. Paradoxically, at low concentrations, CO has demonstrated cyto- and tissue-protective effects in various animal models of organ injury. The antioxidant properties of low concentrations of CO (100–200 ppm) result from its ability to inhibit intracellular sources of ROS that include heme proteins NADPH oxidase and cytochrome c oxidase and mitochondrial complexes II, III, and IV. The ability of CORM-A1 to inhibit the major components of endogenous oxidant-generating machinery, including NADPH oxidase and mitochondrial oxidation, largely explains the antioxidant potencies of CO (2–5, 12, 25, 30, 31, 40, 48). The protective effects of low concentrations of CO against oxidative stress- and inflammation-induced injury have been demonstrated in the cerebral circulation, lungs, and other organs (2–5, 8, 26, 27, 30, 31, 38, 40, 48). The neuroprotective effects of gaseous CO have been demonstrated in the Rice-Vanucci model of neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in rats (38). Preconditioning of rat pups with low-range gaseous CO prevented neuronal hippocampal hypoxia/ischemia-induced neuronal death in the developing brain.

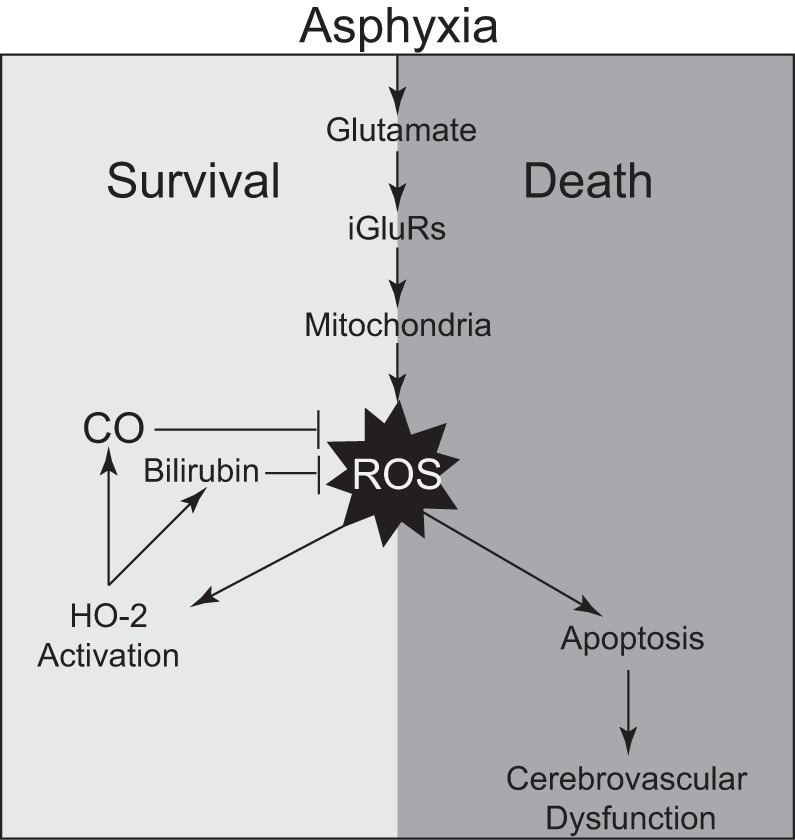

We propose the mechanism of the cytoprotective effect of astrocyte-produced CO against cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by prolonged neonatal asphyxia (Fig. 9). Glutamate excitotoxicity plays a central role in the pathogenesis of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (6, 7, 13, 15, 17, 28, 32, 43, 45, 46). Excessive amounts of glutamate released in the brain during asphyxia interact with various iGluRs expressed in astrocytes (33). iGluR activation initiates excessive production of ROS in the mitochondria, leading to neurovascular death by apoptosis and producing cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cortical astrocytes abundantly express constitutive HO-2, an oxidant-sensitive enzyme (4, 5, 31, 33, 47) that is acutely activated by ROS in the asphyxic brain. CO and bilirubin, the products of HO-catalyzed heme cleavage, are potent antioxidants that reduce mitochondrial ROS production (CO) and scavenge preformed ROS (bilirubin). The neuroprotective role of CO has been demonstrated in other models of perinatal hypoxia-ischemia (38). Overall, ROS elevations in the asphyxic brain have dual functions as potent inducers of cell death and internal triggers of cell survival. ROS act as signaling molecules that increase the activity of HO-2, initiating an antioxidant mechanism. ROS-dependent activation of the astrocyte HO/CO system reduces brain oxidative stress, prevents neurovascular cell death by apoptosis, promotes cell survival, and protects against sustained cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by asphyxia.

Fig. 9.

A proposed mechanism of the cytoprotective effect of astrocyte-produced carbon monoxide (CO) against cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by prolonged neonatal asphyxia. HO-2, heme oxygenase-2; iGluRs, ionotropic glutamate receptors.

Overall, our findings demonstrate the importance of the astrocyte HO/CO system as an endogenous cytoprotection mechanism against asphyxia-induced cerebral vascular dysfunction. We also provide experimental evidence that CORM-A1 efficiently prevents cerebral vascular insufficiencies caused by prolonged neonatal asphyxia. Based on our findings, we propose a novel mechanism-based antioxidant therapy for neonatal asphyxia. Systemic administration of CO donors can be used as a novel approach to protect cerebrovascular function and prevent neonatal brain injury caused by asphyxia.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1-HL-034059 (to C. W. Leffer), RO1-HL-42851 (to C. W. Leffer), and RO1-NS-101717 (to H. Parfenova).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.P., M.P., S.B., and C.W.L. conceived and designed research; H.P., A.L.F., J.L., S.B., and C.W.L. analyzed data; H.P., M.P., J.L., S.B., and C.W.L. interpreted results of experiments; H.P., J.L., and S.B. prepared figures; H.P. and C.W.L. drafted manuscript; H.P., M.P., and C.W.L. edited and revised manuscript; H.P., M.P., J.L., and C.W.L. approved final version of manuscript; A.L.F., J.L., and S.B. performed experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahearne CE, Boylan GB, Murray DM. Short and long term prognosis in perinatal asphyxia: An update. World J Clin Pediatr 5: 67–74, 2016. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basuroy S, Bhattacharya S, Tcheranova D, Qu Y, Regan RF, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. HO-2 provides endogenous protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis caused by TNF-α in cerebral vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C897–C908, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00032.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basuroy S, Bhattacharya S, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Nox4 NADPH oxidase mediates oxidative stress and apoptosis caused by TNF-alpha in cerebral vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C422–C432, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00381.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basuroy S, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. CORM-A1 prevents blood-brain barrier dysfunction caused by ionotropic glutamate receptor-mediated endothelial oxidative stress and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C1105–C1115, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00023.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basuroy S, Tcheranova D, Bhattacharya S, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Nox4 NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species, via endogenous carbon monoxide, promote survival of brain endothelial cells during TNF-α-induced apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C256–C265, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00272.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bel F, Groenendaal F. Drugs for neuroprotection after birth asphyxia: Pharmacologic adjuncts to hypothermia. Semin Perinatol 40: 152–159, 2016. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Pathophysiology of an hypoxic-ischemic insult during the perinatal period. Neurol Res 27: 246–260, 2005. doi: 10.1179/016164105X25216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carratu P, Pourcyrous M, Fedinec A, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Endogenous heme oxygenase prevents impairment of cerebral vascular functions caused by seizures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1148–H1157, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00091.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng G, Sun J, Wang L, Shao X, Zhou W. Effects of selective head cooling on cerebral blood flow and metabolism in newborn piglets after hypoxia-ischemia. Early Hum Dev 87: 109–114, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi DW, Rothman SM. The role of glutamate neurotoxicity in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Annu Rev Neurosci 13: 171–182, 1990. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daley ML, Pourcyrous M, Timmons SD, Leffler CW. Assessment of cerebrovascular autoregulation: changes of highest modal frequency of cerebrovascular pressure transmission with cerebral perfusion pressure. Stroke 35: 1952–1956, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000133690.94288.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desmard M, Boczkowski J, Poderoso J, Motterlini R. Mitochondrial and cellular heme-dependent proteins as targets for the bioactive function of the heme oxygenase/carbon monoxide system. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 2139–2155, 2007. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vries LS, Cowan FM. Evolving understanding of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the term infant. Semin Pediatr Neurol 16: 216–225, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.du Plessis AJ, Volpe JJ. Perinatal brain injury in the preterm and term newborn. Curr Opin Neurol 15: 151–157, 2002. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med 351: 1985–1995, 2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goddard-Finegold J. The neurologically compromised fetus. Semin Perinatol 17: 304–311, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez FF, Ferriero DM. Neuroprotection in the newborn infant. Clin Perinatol 36: 859–880, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunn AJ, Bennet L. Fetal hypoxia insults and patterns of brain injury: insights from animal models. Clin Perinatol 36: 579–593, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harsono M, Pourcyrous M, Jolly EJ, de Jongh Curry A, Fedinec AL, Liu J, Basuroy S, Zhuang D, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Selective head cooling during neonatal seizures prevents postictal cerebral vascular dysfunction without reducing epileptiform activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H1202–H1213, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00227.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins RD, Raju T, Edwards AD, Azzopardi DV, Bose CL, Clark RH, Ferriero DM, Guillet R, Gunn AJ, Hagberg H, Hirtz D, Inder TE, Jacobs SE, Jenkins D, Juul S, Laptook AR, Lucey JF, Maze M, Palmer C, Papile L, Pfister RH, Robertson NJ, Rutherford M, Shankaran S, Silverstein FS, Soll RF, Thoresen M, Walsh WF; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Hypothermia Workshop Speakers and Moderators . Hypothermia and other treatment options for neonatal encephalopathy: an executive summary of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD workshop. J Pediatr 159: 851–858.e1, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanu A, Leffler CW. Roles of glia limitans astrocytes and CO in ADP-induced pial arteriolar dilation in newborn pigs. Stroke 40: 930–935, 2009. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.533786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson M, Tooley JR, Satas S, Hobbs CE, Chakkarapani E, Stone J, Porter H, Thoresen M. Delayed hypothermia as selective head cooling or whole body cooling does not protect brain or body in newborn pig subjected to hypoxia-ischemia. Pediatr Res 64: 74–80, 2008. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318174efdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leffler CW, Mirro R, Shanklin DR, Armstead WM, Shibata M. Light/dye microvascular injury selectively eliminates hypercapnia-induced pial arteriolar dilation in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H623–H630, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leffler CW, Parfenova H, Fedinec AL, Basuroy S, Tcheranova D. Contributions of astrocytes and CO to pial arteriolar dilation to glutamate in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2897–H2904, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00722.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leffler CW, Parfenova H, Jaggar JH. Carbon monoxide as an endogenous vascular modulator. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1–H11, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00230.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Fedinec AL, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Enteral supplements of a carbon monoxide donor CORM-A1 protect against cerebrovascular dysfunction caused by neonatal seizures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 193–199, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Pourcyrous M, Fedinec AL, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Preventing harmful effects of epileptic seizures on cerebrovascular functions in newborn pigs: does sex matter? Pediatr Res 82: 881–887, 2017. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLean C, Ferriero D. Mechanisms of hypoxic-ischemic injury in the term infant. Semin Perinatol 28: 425–432, 2004. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pappas A, Korzeniewski SJ. Long-term cognitive outcomes of birth asphyxia and the contribution of identified perinatal asphyxia to cerebral palsy. Clin Perinatol 43: 559–572, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parfenova H, Leffler CW. Cerebroprotective functions of HO-2. Curr Pharm Des 14: 443–453, 2008. doi: 10.2174/138161208783597380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parfenova H, Leffler CW, Basuroy S, Liu J, Fedinec AL. Antioxidant roles of heme oxygenase, carbon monoxide, and bilirubin in cerebral circulation during seizures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 1024–1034, 2012. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parfenova H, Neff RA III, Alonso JS, Shlopov BV, Jamal CN, Sarkisova SA, Leffler CW. Cerebral vascular endothelial heme oxygenase: expression, localization, and activation by glutamate. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1954–C1963, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parfenova H, Tcheranova D, Basuroy S, Fedinec AL, Liu J, Leffler CW. Functional role of astrocyte glutamate receptors and carbon monoxide in cerebral vasodilation response to glutamate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H2257–H2266, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01011.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pourcyrous M. Cerebral hemodynamic measurements in acute versus chronic asphyxia. Clin Perinatol 26: 811–828, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0095-5108(18)30021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pourcyrous M, Leffler CW, Bada HS, Korones SB, Busija DW. Brain superoxide anion generation in asphyxiated piglets and the effect of indomethacin at therapeutic dose. Pediatr Res 34: 366–369, 1993. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199309000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pourcyrous M, Leffler CW, Bada HS, Korones SB, Busua DW. Brain superoxide anion generation during asphyxia and reventilation in newborn pigs. Pediatr Res 28: 618–621, 1990. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199012000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pourcyrous M, Parfenova H, Bada HS, Korones SB, Leffler CW. Changes in cerebral cyclic nucleotides and cerebral blood flow during prolonged asphyxia and recovery in newborn pigs. Pediatr Res 41: 617–623, 1997. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199705000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Queiroga CS, Tomasi S, Widerøe M, Alves PM, Vercelli A, Vieira HL. Preconditioning triggered by carbon monoxide (CO) provides neuronal protection following perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. PLoS One 7: e42632, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rainaldi MA, Perlman JM. Pathophysiology of birth asphyxia. Clin Perinatol 43: 409–422, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryter SW, Ma KC, Choi AMK. Carbon monoxide in lung cell physiology and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 314: C211–C227, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00022.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saugstad OD, Vento M, Ramji S, Howard D, Soll RF. Neurodevelopmental outcome of infants resuscitated with air or 100% oxygen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neonatology 102: 98–103, 2012. doi: 10.1159/000333346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shankaran S, Laptook AR. Hypothermia as a treatment for birth asphyxia. Clin Obstet Gynecol 50: 624–635, 2007. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31811eba5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solberg R, Longini M, Proietti F, Perrone S, Felici C, Porta A, Saugstad OD, Buonocore G. DHA reduces oxidative stress after perinatal asphyxia: a study in newborn piglets. Neonatology 112: 1–8, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000454982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Bel F, Groenendaal F. Long-term pharmacologic neuroprotection after birth asphyxia: where do we stand? Neonatology 94: 203–210, 2008. doi: 10.1159/000143723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vannucci RC. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Am J Perinatol 17: 113–120, 2000. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vannucci SJ, Hagberg H. Hypoxia-ischemia in the immature brain. J Exp Biol 207: 3149–3154, 2004. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xi Q, Tcheranova D, Basuroy S, Parfenova H, Jaggar JH, Leffler CW. Glutamate-induced calcium signals stimulate CO production in piglet astrocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H428–H433, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01277.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zimmermann A, Leffler CW, Tcheranova D, Fedinec AL, Parfenova H. Cerebroprotective effects of the CO-releasing molecule CORM-A1 against seizure-induced neonatal vascular injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2501–H2507, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00354.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]