Abstract

Autophagy plays many physiological and pathophysiological roles. However, the roles and the regulatory mechanisms of autophagy in response to viral infections are poorly defined in teleost fish, such as grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), which is one of the most important aquaculture species in China. In this study, we found that both grass carp reovirus (GCRV) infection and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatment induced the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in C. idella kidney cells and stimulate autophagy. Suppressing ROS accumulation with N-acetyl-l-cysteine significantly inhibited GCRV-induced autophagy activation and enhanced GCRV replication. Although ROS-induced autophagy, in turn, restricted GCRV replication, further investigation revealed that the multifunctional cellular protein high-mobility group box 1b (HMGB1b) serves as a heat shock protein 70 (HSP70)–dependent, pro-autophagic protein in grass carp. Upon H2O2 treatment, cytoplasmic HSP70 translocated to the nucleus, where it interacted with HMGB1b and promoted cytoplasmic translocation of HMGB1b. Overexpression and siRNA-mediated knockdown assays indicated that HSP70 and HMGB1b synergistically enhance ROS-induced autophagic activation in the cytoplasm. Moreover, HSP70 reinforced an association of HMGB1b with the C. idella ortholog of Beclin 1 (a mammalian ortholog of the autophagy-associated yeast protein ATG6) by directly interacting with C. idella Beclin 1. In summary, this study highlights the antiviral function of ROS-induced autophagy in response to GCRV infection and reveals the positive role of HSP70 in HMGB1b-mediated autophagy initiation in teleost fish.

Keywords: autophagy, heat shock protein (HSP), innate immunity, Beclin-1 (BECN1), oxidative stress, viral replication, Ctenopharyngodon idella, GCRV, HMGB1, HSP70, innate immunity

Introduction

Autophagy is a fundamental mechanism by which cells degrade dysfunctional organelles, misfolded proteins, and other macromolecules and recycle nutrients from unnecessary cellular components (1–3). Under normal conditions, autophagy occurs at a basal level that is important for maintaining normal cellular homeostasis. Upon stress, such as nutrient starvation, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and pathogen infection, autophagy is rapidly initiated (1, 3, 4). Mature autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes to form single-membraned autolysosomes, where enzymes in lysosomes degrade the contents in the autophagosomes (2, 5). Autophagy induces the modification of the soluble form microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3)-I to the lipid-modified form LC3-II (6). LC3-II conjugates on the membrane of autophagosomes and is commonly used as a marker protein for autophagosomes. Beclin 1, the mammalian ortholog of yeast ATG6, is regarded as an essential component for the initiation of conventional autophagy (6). However, the essential role of fish Beclin 1 in autophagy regulation remains unclear, although orthologs of Beclin 1 have been identified in some fish species (7).

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein is conserved chromatin-associated nuclear protein (8). Although pathogenic stimulation or stress treatment induce nuclear HMGB1 to shuttle to the cytoplasm, where HMGB1 is further actively secreted or passively released to the extracellular space (9, 10), HMGB1 plays multiple roles in physiological and pathological processes in different cellular fractions (11). Recently, HMGB1 has been reported to play important nuclear, cytosolic, and extracellular roles in the regulation of the autophagy process under oxidative stress, starvation conditions, or chemotherapy treatment (12–15). Reactive oxygen species (ROS)2 can trigger HMGB1 translocation to the cytosol where HMGB1 interacts with Beclin 1 and subsequently induces autophagy (12). Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a family of conserved chaperone proteins that act in response to physiological and environmental stresses (16). HSP70 is involved in the regulation of fundamental cellular processes, such as signal transduction, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and innate immunity (17, 18). HSP70 has also been reported to inhibit starvation or rapamycin-induced autophagy via the increased v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT) pathway (19, 20).

Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) is one of the most important aquaculture species in China. Grass carp reovirus (GCRV), a dsRNA virus, causes severe hemorrhagic disease in juvenile grass carp (21). Previous studies demonstrated pivotal roles of grass carp HMGBs (HMGB1a, HMGB1b, HMGB2a, HMGB2b, HMGB3a, and HMGB3b) in the antiviral immune response against GCRV infection (21–23). Similar to mammalian HMGBs, grass carp HMGBs localize in the nucleus in the resting stage, whereas GCRV infection or pathogenic stimuli induce HMGB nucleocytoplasmic translocation, and subcellular localization of HMGB1b is more sensitive to pathogenic stimuli compared with other HMGBs (24). Intramolecular interaction between HMG boxes and C-tail domains has been identified to mediate nucleocytoplasmic translocation of HMGBs (24). However, the intermolecular interaction that regulates the subcellular localization and functions of fish HMGB1 remains unclear.

In this study, HSP70 was identified to interact with HMGB1b upon GCRV infection. GCRV infection induced ROS-mediated autophagy, which, in turn, inhibited GCRV replication. ROS treatment induced HSP70 translocation to the nucleus, where it interacted with HMGB1b and promoted HMGB1b cytoplasmic shuttling. In the cytoplasm, HSP70 and HMGB1b synergistically enhanced ROS-induced autophagy. HSP70 also promoted HMGB1b–Beclin 1 association via direct interaction with Beclin 1. Our results highlight the antiviral role of ROS-induced autophagy in response to GCRV infection. Differing from that in mammals, this study uncovers that cytoplasmic HMGB1b-mediated autophagic activation depends on HSP70 in teleosts.

Results

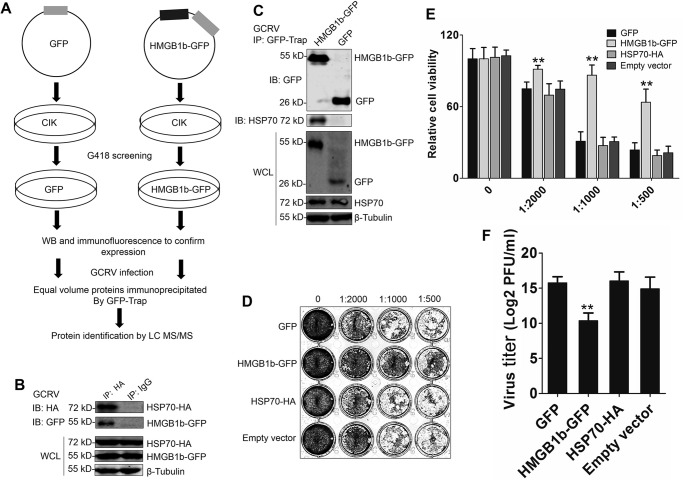

HSP70 interacts with HMGB1b upon GCRV infection

To define the molecular action of HMGB1b during GCRV infection, we performed affinity purification for HMGB1b from stable CIK cells and analyzed HMGB1b-binding proteins by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 1A). We identified 705 candidate interactive proteins from the proteomic dataset, of which 31 proteins were matched with at least four unique peptides (≥4) (Table S1). Besides HMGB1b, HSP70, an ortholog of mammalian HSP72 (Fig. S1), is the top candidate and has the most matched peptides (unique peptides = 13). Thus, we investigated the role of HSP70 in HMGB1b-dependent antiviral activity. The interaction between HMGB1b and HSP70 was verified through co-IP upon GCRV infection (Fig. 1, B and C). A standard plaque assay and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay indicated that HMGB1b overexpression significantly promoted cell viability, whereas HSP70 overexpression had no influence on GCRV-induced cell death (Fig. 1, D and E). The viral titer indicated that HMGB1b, but not HSP70, possessed significant antiviral activity (Fig. 1F). These results imply that HSP70 may play an indirect role in HMGB1b-mediated antiviral immunity.

Figure 1.

Identification of HSP70 as an interacting partner of HMGB1b upon GCRV infection. A, strategy for analyzing the interacting partners of HMGB1b via affinity purification and LC-MS/MS. GFP and HMGB1b-GFP stably transfected CIK cells were obtained by G418 selection. IP was carried out using GFP trap beads. LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on a Q Exactive mass spectrometer. B and C, verifying the interaction between HSP70 and HMGB1b via co-IP assay. B, CIK cells were cotransfected with HMGB1b-GFP and HSP70-HA for 24 h. Then the cells were infected with GCRV for another 24 h. Co-IP was performed with anti-HA monoclonal Ab and mouse IgG (control) and immunoblot (IB) analysis with the respective Abs as shown. C, both HMGB1b-GFP and GFP overexpression CIK cell lines were infected with GCRV for 24 h. The cell lysate was subjected to IP by GFP trap beads. Then the IP samples and whole-cell lysate (WCL) were used for IB analysis with anti-HSP70, anti-GFP, and anti-β-tubulin Abs. D–F, antiviral activity analyses of HMGB1b and HSP70 to GCRV infection. CIK cells seeded in 24-well plates overnight were transiently transfected with 600 ng of HMGB1b-GFP, HSP70-HA, or the corresponding empty plasmids, respectively. Twenty-four hours later, the transfected cells were infected with GCRV at an m.o.i. of 0.1. Forty-eight hours later, the supernatants were collected as titer samples. Virus titers were measured by standard plaque assay in 24-well plates and cell viability assay. D, standard plaque assay. CIK cells were plated in 24-well plates for 12 h and treated with titer samples of HMGB1b-GFP, GFP, HSP70-HA, and empty vector (pcDNA3.1) at different dilution rates (0, 1:500, 1:1000, and 1:2000). Thirty-six hours later, the viable cells were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.05% (w/v) crystal violet. E, cell viability was assessed by MTT assay in 96-well plates. F, virus titers supernatants were measured by PFU assay. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 4). **, p < 0.01.

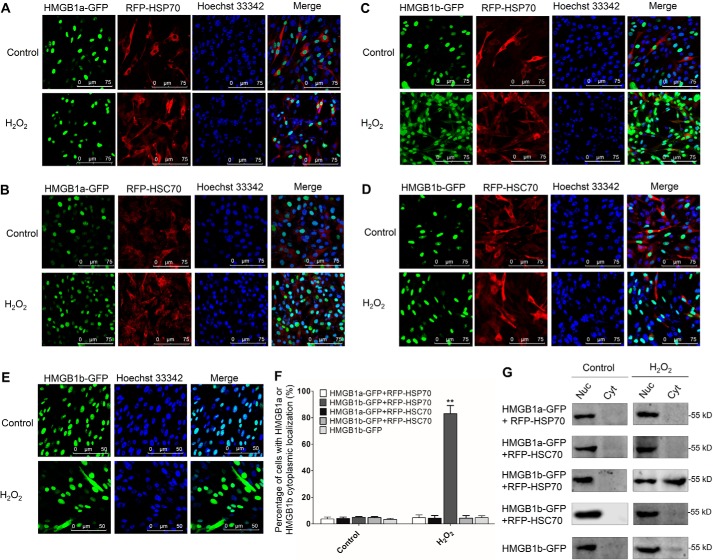

HSP70 promotes H2O2-induced cytoplasmic translocation of HMGB1b

Given the previous report that mammalian HSP70 negatively regulates oxidative stress-induced HMGB1 cytoplasmic translocation (10), we established cell lines that stably co-expressed HMGB1a-GFP/RFP-HSP70, HMGB1a-GFP/RFP-HSC70, HMGB1b-GFP/RFP-HSP70, and HMGB1b-GFP/RFP-HSC70 and examined the influence of HSP70s on the H2O2-induced dynamic localization of HMGB1s. As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, H2O2 treatment did not induce obvious cytoplasmic translocation of HMGB1a upon RFP-HSP70 or RFP-HSC70 overexpression, but for HMGB1b, significant cytoplasmic shuttling of HMGB1b was evoked upon H2O2 treatment in the presence of RFP-HSP70 (Fig. 2C). However, H2O2 treatment induced no or a few cells that displayed an HMGB1b cytoplasmic presence in HMGB1b-GFP/RFP-HSC70 co-expressing and HMGB1b-GFP single-expressing cells (Fig. 2, D and E). Consistently, cell percentage analysis and Western blot (WB) analysis of subcellular fractions displayed a significant cytoplasmic presence of HMGB1b in HMGB1b-GFP/RFP-HSP70 co-expressing cells (Fig. 2, F and G). All of these results indicate that HSP70 is required for H2O2-induced HMGB1b cytoplasmic translocation, which is contrary in mammals.

Figure 2.

HSP70 specifically promotes H2O2-induced nucleocytoplasmic translocation of HMGB1b. A–E, CIK cells stably expressing HMGB1a-GFP and RFP-HSP70 (A), HMGB1a-GFP and RFP-HSC70 (B), HMGB1b-GFP and RFP-HSP70 (C), HMGB1b-GFP and RFP-HSC70 (D), or HMGB1b-GFP (E) were seeded on microscope coverglasses in 12-well plates for 24 h at about 90% confluence and treated with H2O2 at a nontoxic dose (0.15 mm) or PBS for 36 h. Then the cells were fixed with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde and stained with Hoechst 33342. Subsequently, all samples were visualized using a confocal microscope. F, counting analysis of cells with HMGB1a or HMGB1b cytoplasmic localization. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 4). **, p < 0.01. G, nucleocytoplasmic distribution of HMGBs was examined by WB. The indicated cells were treated with H2O2 or PBS for 36 h in 10-cm dishes. Then the nuclear (Nuc) and cytoplasmic (Cyt) proteins were extracted. The protein levels of HMGB1b-GFP in different cell fractions were examined by IB analysis with GFP Ab.

H2O2 induces HSP70 nuclear translocation and interaction with HMGB1b

In mammals, HSP72 translocates to the nucleus in response to oxidative stress (10). To elucidate the effect of oxidative stress on grass carp HSP70 subcellular localization, RFP-HSP70 overexpression cells were treated with or without H2O2, and the cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted to determine HSP70 localization. WB analysis indicated that H2O2 treatment induced significant endogenous and exogenous HSP70 expression in the nucleus (Fig. 3, A and B). A co-IP assay demonstrated the interaction between HSP70 and HMGB1b in the nuclear fraction after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 3C). This result agrees with a report that oxidative stress induces HSP72 nuclear translocation and subsequent interaction with HMGB1 in the nucleus (10). The interaction between HSP70 and HMGB1b in the nucleus is required for H2O2-induced HMGB1 cytoplasmic translocation.

Figure 3.

H2O2 induces HSP70 nuclear translocation to interact with HMGB1b. A and B, H2O2 induces nuclear translocation of HSP70. A, verifying the specificity of the HSP70 Ab. The cell lysate of CIK and RFP-HSP70 stably transfected cells was subjected to IB analysis with HSP70 Ab. B, nucleocytoplasmic accumulation of HSP70 upon H2O2 challenge. Nuclear (Nuc) and cytoplasmic (Cyt) proteins from H2O2-treated or untreated RFP-HSP70–expressing cells were subjected to WB examination by anti-HSP70 Ab, anti-histone H3 Ab as a nuclear protein marker, and anti-β-tubulin as a cytoplasmic protein marker. C, HMGB1b interacts with HSP70 in the nucleus. HMGB1b-GFP was transfected into CIK cells for 16 h and treated with H2O2 for another 24 h. Then nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted and subjected to IP with GFP trap beads. IB analysis was conducted with anti-HSP70, anti-GFP, anti-histone H3, and anti-β-tubulin Abs.

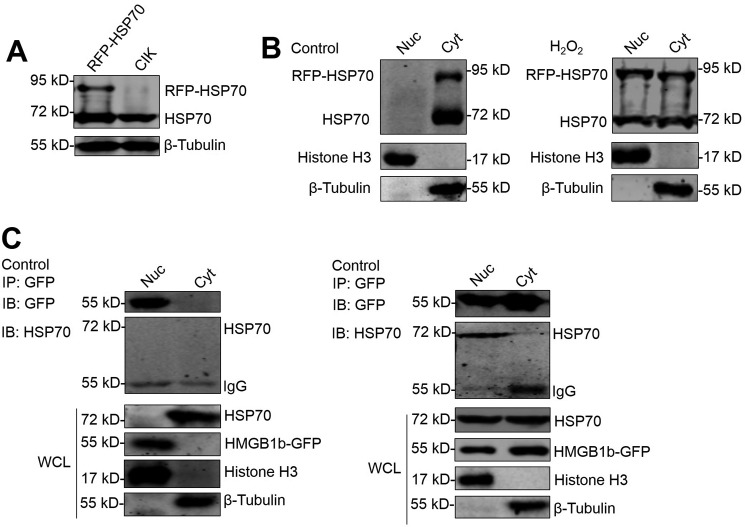

H2O2 treatment evokes autophagy in CIK cells

Autophagy is a self-degradative process that is important for maintaining cellular homeostasis (25). A number of physiologically relevant insults, e.g. ROS and rapamycin, can induce autophagy (4, 26). In this study, we employed both H2O2 and rapamycin (an autophagy promotor) treatment to induce autophagy, as evidenced by GFP-LC3–labeled autophagosomes and RFP-LAMP2–labeled lysosomes in CIK cells. Compared with control cells, H2O2 and rapamycin treatment significantly enhanced the accumulation of GFP-LC3 puncta, which are called autophagosomes, in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4, A and C). H2O2 and rapamycin treatment induced strict fusion between GFP-LC3–labeled autophagosomes and RFP-LAMP2–labeled lysosomes (Fig. 4, B and C). Autophagy activation is accompanied by the conversion of cytosolic LC3-I to membrane-bound LC3-II (27). To assess the formation of endogenous LC3-II, WB analysis was used to examine the expression levels of LC3-I and LC3-II. The specificity of the anti-LC3 antibody (Ab) was verified (Fig. 4D). WB analysis showed that H2O2 treatment significantly enhanced LC3-II expression and the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio (Fig. 4, E and F). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed the ultrastructure of double-membraned autophagosomes and monolayer-membraned autolysosomes upon H2O2 and rapamycin stimulation (Fig. 4G). In the late stage of H2O2 and rapamycin treatment (48 h), the number of autolysosomes was more than that of autophagosomes (count of TEM data). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that H2O2 and rapamycin treatments are sufficient to initiate autophagy activation and subsequent enhancement of autophagy flux. This is the first evidence of ROS-induced autophagy in fish cells.

Figure 4.

H2O2 treatment induces autophagy in CIK cells. A, H2O2 promotes autophagosome production. CIK cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 in 12-well plates with coverglasses. 16 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 0.15 mm H2O2, 100 nm rapamycin, or an equal volume of PBS (control) for 24 h. Then the cells were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde and stained with Hoechst 33342. Finally, the samples were visualized by confocal microscopy. The GFP-LC3 puncta indicate autophagosomes. B, H2O2 promotes fusion between GFP-LC3–labeled autophagosomes and RFP-LAMP2–labeled lysosomes. CIK cells were cotransfected with GFP-LC3 and RFP-LAMP2. Then the cells were treated with rapamycin or H2O2 and prepared for confocal microscopy as described above. The colocalization between GFP-LC3 and RFP-LAMP2 represents autolysosomes. C, quantifying the percentage of cells with autophagosomes and autolysosomes. Autophagosomes were quantified by the number of cells with at least five GFP-LC3-postive puncta per cell, accounting for the GFP-LC3–positive cells. Autolysosomes were calculated as the quantity of cells with GFP-LC3 and RFP-LAMP2 co-localization, accounting for all GFP-LC3 and RFP-LAMP2–cotransfected cells. Mean ± S.D.; **, p < 0.01 compared with GFP-LC3–transfected cells. D, verifying the specificity of the anti-LC3 polyclonal Ab. CIK cells were transfected with or without GFP-LC3. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were harvested for WB analysis using anti-GFP and anti-LC3 Abs. E and F, analyzing the impact of H2O2 on LC3 in CIK cells. CIK cells were subjected to H2O2 treatment for 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h. The cell lysate was used for WB analysis with anti-LC3 Ab. β-Tubulin was employed as an internal control. The relative intensity of LC3-II to LC3-I was quantified by ImageJ software (**, p < 0.01; *, 0.01 < p < 0.05). G, ultrastructure features of H2O2-induced autophagic vacuoles in CIK cells. CIK cells were treated with H2O2 and rapamycin for 48 h and then prepared for TEM. Autolysosomes, autophagosomes, and other organelles are indicated. Red arrowheads indicate double-membraned structures of autophagosomes.

GCRV infection promotes autophagy activation by eliciting ROS accumulation

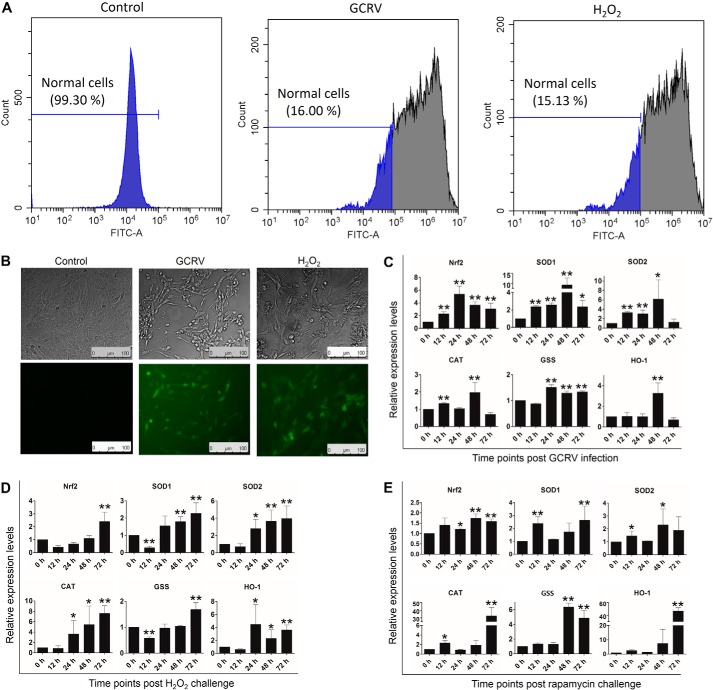

To evaluate the relationship between ROS and GCRV, we examined ROS production in GCRV-infected CIK cells using the DCFH-DA probe. Compared with normal cells, GCRV infection induced excessive ROS production in ∼84% of cells, as potent as the H2O2 treatment, which was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 5A) and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5B). Excessive ROS generation promotes activation of the antioxidant pathway to protect cells from oxidative stress and damage (28). The NF-E2–related factor 2 antioxidant response element (Nrf2-ARE) pathway is capable of stimulating the activity of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), GSH synthetase (GSS), and hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1)), which contribute to resistance to a variety of diseases (28). To this end, we examined the expression levels of Nrf2, SOD1, SOD2, CAT, GSS, and HO-1 at different time points after GCRV infection and H2O2 and rapamycin treatment. GCRV infection induced up-regulation of Nrf2 and SOD1 from 12 h to 72 h, SOD2 from 12 h to 48 h, GSS from 24 h to 72 h, CAT at 12 h and 48 h, and HO-1 at 48 h (Fig. 5C). After H2O2 treatment, Nrf2, SOD1, and GSS were rapidly inhibited at 12 h and then recovered to normal levels and were up-regulated at the following time points. The mRNA levels of SOD2, CAT, and HO-1 were significantly enhanced at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, rapamycin treatment also remarkably promoted the expression levels of Nrf2, SOD1, SOD2, CAT, GSS, and HO-1 at different time points (Fig. 5E). These results prove that GCRV infection, oxidative stress, and autophagy initiation evoke antioxidant pathway activation.

Figure 5.

GCRV infection facilitates the production of ROS and antioxidation in CIK cells. A and B, GCRV infection induces ROS production in CIK cells. CIK cells were subjected to GCRV infection for 24 h or H2O2 treatment (positive control) for 1 h. Then the cells were supplied with the DCFH-DA probe in supernatants according to the ROS assay kit. Finally, the cells were examined by flow cytometry (A) and fluorescence microscopy (B). The percentage represents nonoxidized cells (normal cells), and green fluorescence indicates oxidized cells. C–E, GCRV, H2O2 and rapamycin induce up-regulation of antioxidative genes in CIK cells. CIK cells were infected with GCRV or treated with H2O2 or rapamycin at the indicated time points. The expression levels of the antioxidative genes Nrf2, SOD1, SOD2, CAT, GSS, and HO-1 were quantified by qRT-PCR. Error bars indicate S.D. **, p < 0.01; *, 0.01 < p < 0.05.

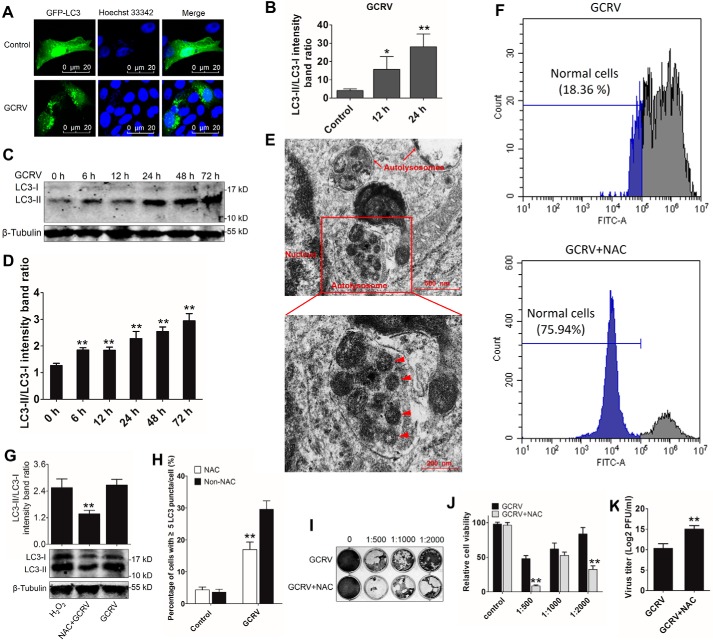

To explore whether GCRV can initiate autophagy, we evaluated autophagosome formation at 12 h and 24 h after GCRV infection. As shown in Fig. 6, A and B, GCRV infection markedly enhanced GFP-LC3 punctum formation compared with control cells. WB analysis indicated that GCRV infection significantly increased LC3-II expression and the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio from 6 h to 72 h in CIK cells (Fig. 6, C and D). TEM analysis revealed autolysosomes and virions captured in autolysosomes in GCRV-infected CIK cells (Fig. 6E). These data demonstrate that GCRV infection induces autophagy activation. To investigate the role of ROS in GCRV-induced autophagy initiation, a ROS inhibitor, N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) was used to eliminate ROS. First, the efficiency of NAC was examined by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 6F, NAC pretreatment significantly inhibited GCRV-induced ROS in CIK cells. Interestingly, NAC pretreatment remarkably decreased LC-II expression and autophagosome formation (Fig. 6, G and H). A plaque assay, MTT assay, and virus titer revealed that NAC pretreatment promoted GCRV replication and inhibited cell viability (Fig. 6, I–K). Therefore, suppression of ROS results in inhibition of autophagy activation. Collectively, these results reveal that GCRV infection-induced autophagy activation depends on ROS accumulation.

Figure 6.

GCRV infection promotes autophagy activation in CIK cells. A, imaging of GFP-LC3–labeled autophagosomes induced by GCRV infection. CIK cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 for 16 h and infected with GCRV for another 24 h. Then the cells were fixed and stained for confocal microscopy. B, quantifying the percentage of cells with at least 5 GFP-LC3–positive puncta per cell. Mean ± S.D.; **, p < 0.01 compared with GFP-LC3–transfected cells. C and D, analyses of the ratios of LC3-II/LC3-I upon GCRV infection. CIK cells were infected with GCRV. The cell lysate was used for WB examination with anti-LC3 and β-tubulin Abs at different time points after infection. The intensity of LC3-II/LC3-I was analyzed by ImageJ (**, p < 0.01). E, observation of autolysosomes in GCRV-infected CIK cells using TEM. CIK cells were fixed 48 h after GCRV infection and observed under a transmission electron microscope. The red arrowheads indicate virus particles wrapped in autolysosomes. F, NAC inhibits GCRV-induced ROS accumulation in CIK cells. CIK cells were pretreated with or without NAC for 0.5 h before GCRV infection. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were supplied with the DCFH-DA probe in supernatants according to the ROS assay kit, and the oxidized cells were examined by flow cytometry. G and H, NAC restrains autophagy activation. G, CIK cells were pretreated with NAC for 0.5 h and then treated with H2O2 or infected with GCRV for 24 h. The cell lysate was subjected to WB analysis with anti-LC3 Ab. The ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I was analyzed by ImageJ (**, p < 0.01). H, the autophagosomes were quantified by the percentage of cells with at least five GFP-LC3–positive puncta per cell. Mean ± S.D.; **, p < 0.01 compared with GFP-LC3–transfected cells. I–K, NAC inhibits GCRV replication. I, standard plaque assay. CIK cells were plated in 24-well plates for 12 h and treated with titer samples of GCRV and GCRV+NAC at different dilution rates (0, 1:500, 1:1000, and 1:2000). Thirty-six hours later, viable cells were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.05% (w/v) crystal violet. J, cell viability was assessed by MTT assay in 96-well plates. K, virus titer supernatants were measured by PFU assay. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 4). **, p < 0.01; *, 0.01 < p < 0.05.

Autophagy inhibits GCRV replication in CIK cells

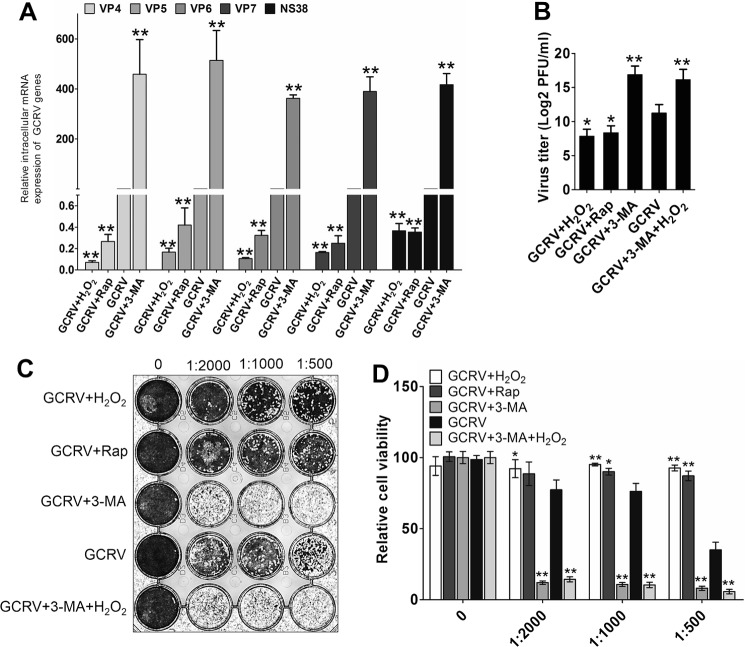

The antiviral or proviral roles of autophagy have been witnessed in the past few years (29). To determine the precise role of autophagy in regulating GCRV infection, CIK cells were pretreated with the autophagic inhibitor 3-methladenine (3-MA) or the autophagy promotors rapamycin and H2O2 and then infected with an equal amount of GCRV. The supernatant from the infected cells was harvested to determine the viral yield. Compared with the mock-treated group, 3-MA pretreatment increased the expression of GCRV genes (VP4, VP5, VP6, VP7, and NS38) by more than 200-fold, whereas rapamycin and H2O2 pretreatment significantly reduced viral gene expression (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, H2O2 treatment induced more robust inhibition of GCRV gene expression compared with rapamycin treatment. Consistently, the viral yield in 3-MA–pretreated cells was higher than in the mock-treated group, whereas H2O2 and rapamycin pretreatment significantly decreased the viral titer (Fig. 7B). A standard plaque assay and MTT assay indicated that 3-MA pretreatment strongly weakened cell viability. Nevertheless, H2O2 and rapamycin pretreatment significantly promoted cell viability in CIK cells, and H2O2 had a more protective effect on cell viability (Fig. 7, C and D). However, H2O2-induced cell survival and inhibition of GCRV replication were eliminated by the presence of 3-MA, which indicated that autophagy is essential for H2O2-evoked cell protection and GCRV suppression. These results suggest that autophagy, especially ROS-induced autophagy, significantly restricts GCRV replication.

Figure 7.

Oxidative stress–induced autophagy inhibits GCRV replication. A–D, CIK cells were pretreated with 0.6% PBS (control), 5 mm 3-MA, 100 nm rapamycin (Rap), 0.15 mm H2O2, and 5 mm 3-MA + 0.15 mm H2O2 for 4 h, respectively, and then infected with GCRV at an m.o.i. of 0.1. The supernatants were harvested at 48 h for titer samples. Subsequently, CIK cells were treated with the titer samples for 24 h, and mRNA expression levels of GCRV VP4, VP5, VP6, VP7, and NS38 were quantified by qRT-PCR (A). Antiviral activities were measured by PFU (B), standard plaque assay (C), and MTT assay (D). Error bars indicate S.D. **, p < 0.01.

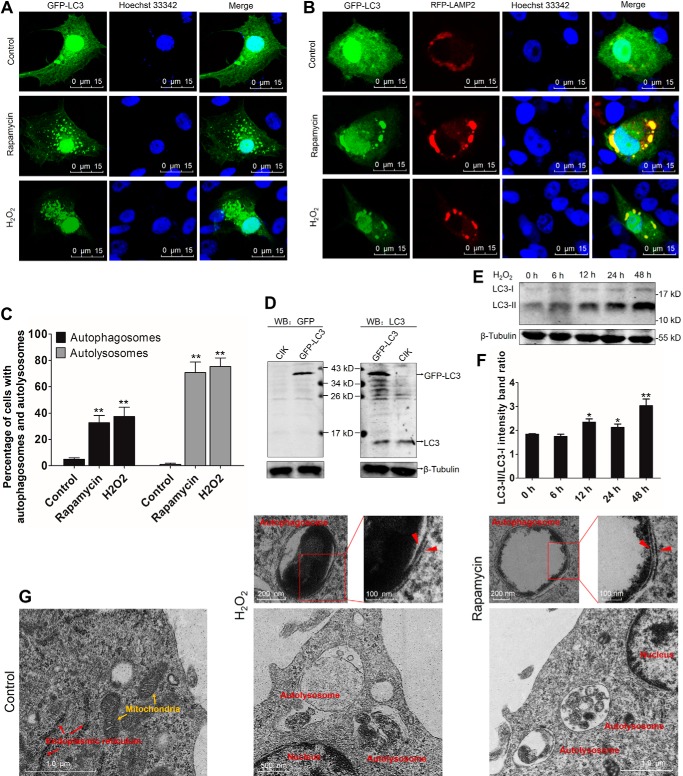

HSP70 and HMGB1b synergistically promote H2O2-induced autophagy

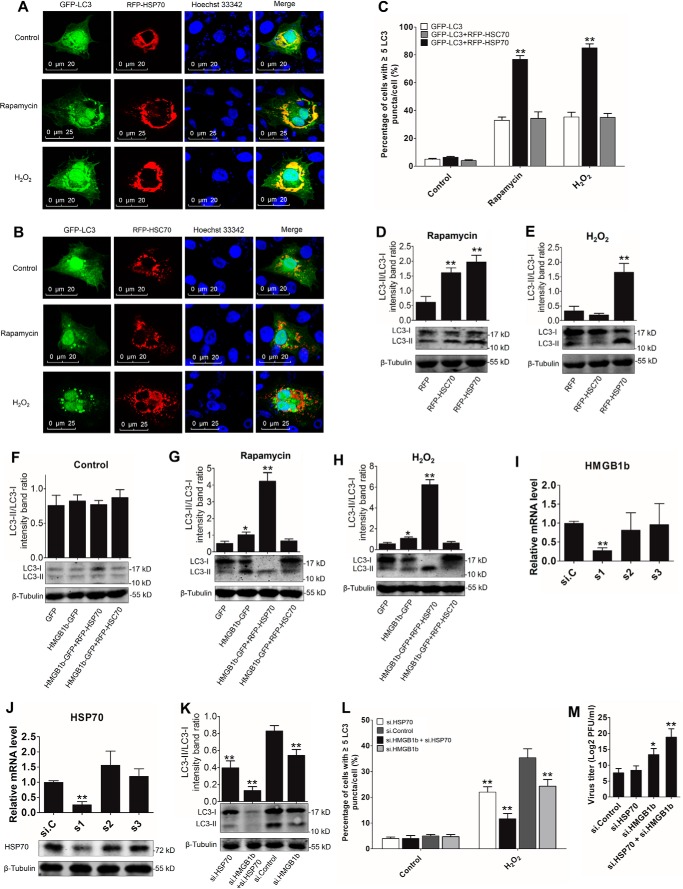

In mammals, both HSP70 and HMGB1 are involved in autophagy regulation (12, 30). To probe the essential roles of grass carp HSP70 and HMGB1b in autophagy modulation, we examined the localization relationships between HSP70, the homologous partner HSC70, and autophagosomes. As shown in Fig. 8, A and B, HSP70 significantly co-localized with LC3-labeled autophagosomes under rapamycin or H2O2 treatment, whereas no obvious co-localization between RFP-HSC70 and GFP-LC3 puncta was observed. HSP70 overexpression significantly enhanced the ratio of cells with LC3 puncta after H2O2 and rapamycin treatment (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that HSP70 participates in the regulation of autophagosome formation. Subsequently, endogenous LC3-II expression was examined in GFP, RFP, RFP-HSP70, RFP-HSC70, HMGB1b-GFP, HMGB1b-GFP/RFP-HSP70, and HMGB1b-GFP/RFP-HSC70 stably transfected cells, respectively. Upon rapamycin treatment, both HSC70 and HSP70 overexpression enhanced LC3-II/LC3-I intensity (Fig. 8D), whereas only HSP70 overexpression significantly increased H2O2-induced LC3-II/LC3-I transformation (Fig. 8E). HMGB1b overexpression also enhanced H2O2- and rapamycin-induced LC3-II/LC3-I transformation (Fig. 8, F–H). Compared with HMGB1b or HSP70 single transfection, HMGB1b and HSP70–co-expressing cells showed a more significant increase in the LC3-II ratio (Fig. 8, G and H). To uncover the roles of endogenic HMGB1b and HSP70 in autophagy regulation, HMGB1b- and HSP70-specific siRNA was used to knock down endogenic HMGB1b and HSP70. Among the synthetic siRNA, s1 of HMGB1b and s1 of HSP70 showed the best interference efficiencies in HMGB1b and HSP70 mRNA levels (Fig. 8, I and J). Further results indicated that knockdown of HMGB1b or HSP70 significantly decreased LC3-II/LC3-I intensity and autophagosome formation (Fig. 8, K and L). Both HMGB1b and HSP70 knockdown resulted in stronger inhibition of autophagy activation. Interestingly, HSP70 knockdown has no significant influence on GCRV replication. However, double knockdown of HMGB1b and HSP70 induced a notable decrease in GCRV titer (Fig. 8M), which means that HSP70 inhibits HMGB1b-mediated antiviral function to GCRV. Collectively, these results demonstrate that both HSP70 and HMGB1b positively participate in autophagy regulation and that HSP70 and HMGB1b synergistically facilitate autophagy activation, which further inhibits GCRV replication.

Figure 8.

HSP70 and HMGB1b synergistically promote autophagy activation. A and B, HSP70, but not HSC70, mainly participates in autophagy formation. CIK cells were cotransfected with GFP-LC3 and RFP-HSP70 or GFP-LC3 and RFP-HSC70 for 16 h. Then the cells were treated with rapamycin or H2O2 for 24 h and prepared for confocal microscope observation. C, quantifying the percentage of cells with at least five GFP-LC3–positive puncta per cell. Mean ± S.D.; **, p < 0.01 compared with GFP-LC3–transfected cells. D and E, HSP70 promotes LC3-II formation. RFP, RFP-HSC70, and RFP-HSP70 stably transfected cells were treated with rapamycin or H2O2 for 24 h. Then the cell lysate was subjected to WB analysis with anti-LC3 Ab. Histograms display the ratios of LC3-II/LC3-I. Error bars indicate S.D. **, p < 0.01. F–H, HSP70 and HMGB1b synergistically facilitate autophagy initiation. GFP, HMGB1b-GFP, HMGB1b-GFP and RFP-HSP70, and HMGB1b-GFP and RFP-HSC70 stably transfected cells were treated with H2O2 or rapamycin for 24 h. Protein levels of LC3 were detected by LC3 Ab. Error bars indicate S.D. **, p < 0.01; *, 0.01 < p < 0.05. I and J, examining the interference efficiency of the HMGB1b and HSP70 siRNA. HMGB1b- and HSP70-specific siRNA along with negative control si.C were transiently transfected into CIK cells. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were harvested for qRT-PCR to quantity the expression levels of HMGB1b and HSP70. Error bars indicate S.D. **, p < 0.01. The interference efficiency of HSP70 siRNA was also examined with anti-HSP70 Ab (J, bottom panel). K, knockdown of HMGB1b and HSP70 inhibits ROS-induced autophagy activation. CIK cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with s1 of HMGB1b or s1 of HSP70 or cotransfected with s1 of HMGB1b and HSP70. Sixteen hours later, the cells were treated with H2O2 for 24 h. Then the cell lysate was collected for WB analysis with anti-LC3 Ab. L, knockdown of HMGB1b and HSP70 restrained autophagosome formation. CIK cells were cotransfected with si.C and GFP-LC3, s1 of HMGB1b and GFP-LC3, s1 of HSP70 and GFP-LC3, and s1 of HSP70 and HMGB1b and GFP-LC3. Then the cells were treated with H2O2 for 24 h. The autophagosomes were quantified by the percentage of cells with at least five GFP-LC3–positive puncta per cell. Mean ± S.D.; **, p < 0.01. M, knockdown HSP70 inhibited HMGB1b-induced GCRV replication. CIK cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA and then infected with GCRV. Finally, the viral titer in the supernatant was tested as described above.

Beclin 1 functions as a positive regulator of autophagy in CIK cells

Mammalian Beclin 1 is an essential component for the initiation of autophagy (6). Previous studies indicated that HMGB1 and HSP70 are involved in Beclin 1-medialted autophagy (31, 32). However, whether piscine Beclin 1 functions in autophagy remains largely unknown. We first identified that Beclin 1 strictly localized in GFP-LC3-labeled autophagosomes (Fig. S2A). Beclin 1 overexpression increased the percentage of CIK cells containing LC3 puncta. Rapamycin or H2O2 treatment induced more LC3 punctum production in Beclin 1 overexpression cells (Fig. S2B). Consistently, Beclin 1 overexpression enhanced LC3-II accumulation in resting cells (Fig. S2, C and D). Compared with cells transfected with an empty vector, Beclin 1 overexpression significantly increased H2O2- and rapamycin-induced LC3-II expression (Fig. S2, E–H). These data suggest that piscine Beclin 1 is an inherent positive regulator of autophagy. To probe the effect of GCRV, H2O2, and rapamycin on Beclin 1 expression, the protein levels of endogenous Beclin 1 were examined by WB analysis in GCRV-infected, H2O2- and rapamycin-treated CIK cells. The specificity of the anti-Beclin 1 Ab was identified in GFP-Beclin 1 and Beclin 1-HA overexpression CIK cells (Fig. S2I). H2O2 treatment induced significant up-regulation of Beclin 1 at 24 h and 48 h (Fig. S2, J and K). The protein levels of Beclin 1 were enhanced from 12 h to 48 h after rapamycin treatment (Fig. S2, L and M). After GCRV infection, the protein levels of Beclin 1 were rapidly and remarkably up-regulated from 6 h to 72 h (Fig. S2, N and O). Therefore, Beclin 1 is involved in the GCRV- and H2O2-induced autophagy pathway.

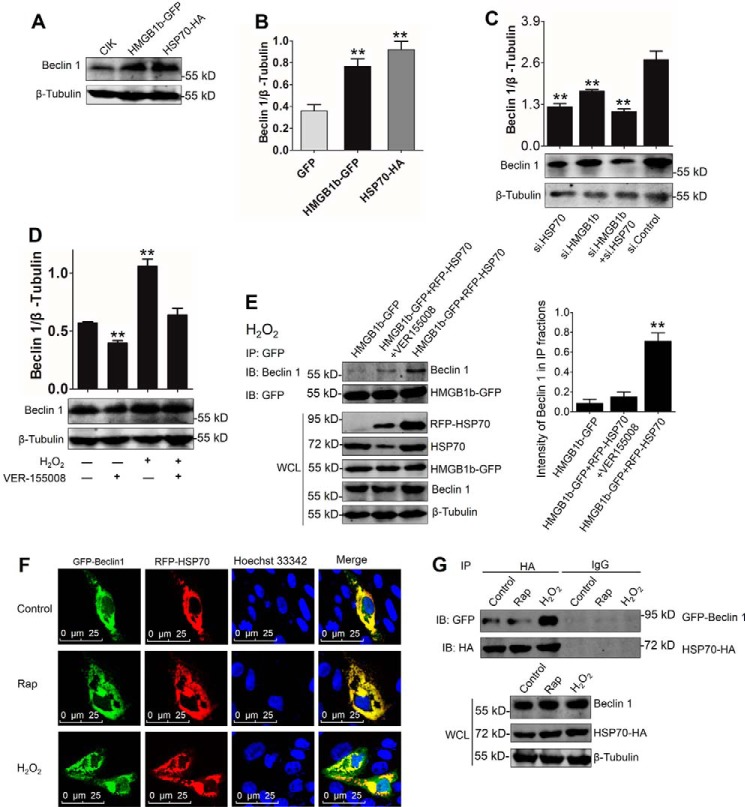

HSP70 enhances H2O2-induced HMGB1b–Beclin 1 association

To assess the regulation of HSP70 and HMGB1b in the Beclin 1 autophagy pathway, we investigated the influence of HSP70 and HMGB1b on Beclin 1 expression. As shown in Fig. 9, A and B, HSP70 and HMGB1b overexpression significantly increased the protein levels of Beclin 1. However, knockdown of HSP70 and HMGB1b significantly inhibited the protein level of Beclin 1 (Fig. 9C). Knockdown of both HMGB1b and HSP70 synergistically restrained Beclin 1 expression. Additionally, the HSP70 inhibitor VER-155008 was used to prove HSP70 function. Upon VER-155008 treatment, Beclin 1 expression was significantly inhibited (Fig. 9D). These results identify the positive roles of HMGB1b and HSP70 in the Beclin 1-mediated autophagy pathway. To explore the regulation mechanism of HSP70 to HMGB1b-Beclin 1 association, the interaction between HMGB1b and Beclin 1 was examined with a co-IP assay. In HMGB1b-GFP stably transfected cells, HMGB1b slightly interacted with Beclin 1. The interaction was significantly enhanced by RFP-HSP70 overexpression and weakened upon VER-155008 treatment (Fig. 9E), indicating that HSP70 plays an essential role in HMGB1b-Beclin 1–mediated autophagy activation. Whether in the resting stage or upon rapamycin or H2O2 treatment, HSP70 and Beclin 1 were clearly colocalized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 9F). The co-IP assay indicated that HSP70 interacted with Beclin 1 under normal conditions and rapamycin or H2O2 treatment, but H2O2 treatment enhanced the interactive intensity between HSP70 and Beclin 1 (Fig. 9G). These results underline that HSP70–Beclin 1 interaction is essential for ROS-induced HMGB1b–Beclin 1 association.

Figure 9.

HSP70 promotes the HMGB1b–Beclin 1 autophagy pathway via interaction with Beclin 1. A and B, HMGB1b or HSP70 overexpression up-regulates Beclin 1 protein levels. CIK cells were transfected with HMGB1b-GFP or HSP70-HA for 24 h and subjected to WB analysis with Beclin 1 and β-tubulin Abs. The relative protein level of Beclin 1 was quantified by ImageJ. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3); **, p < 0.01. C, knockdown of HSP70 or HMGB1b inhibits H2O2-induced protein level of Beclin 1. CIK cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with s1 of HMGB1b, s1 of HSP70, or cotransfected with s1 of HMGB1b and HSP70. Then the cells were treated with H2O2 for 24 h. The cell lysate was collected for WB analysis with anti-Beclin 1 Ab. The histograms display the ratios of LC3-II/LC3-I. Error bars indicate S.D.; **, p < 0.01. D, inhibition of HSP70 by VER155008 reduces the H2O2-induced Beclin 1 protein level. CIK cells were treated with or without 10 nm VER-155008 for 12 h and then supplied with 0.15 μm H2O2 in the medium for another 24 h. The protein levels of Beclin 1 were examined using the anti-Beclin 1 Ab. The relative protein levels of Beclin 1 were quantified by ImageJ. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3); **, p < 0.01. E, left panel, HSP70 promotes the interaction between HMGB1b and Beclin 1. HMGB1b-GFP and RFP-HSP70 stably cotransfected cells were pretreated with or without VER-155008 for 12 h. HMGB1b-GFP stably transfected cells were used as a control. All cells were treated with 0.15 mm H2O2 for 24 h. IP was conducted with GFP trap beads and IB with Beclin 1 and GFP Abs. WCL was used to analyze the indicated proteins. Right panel, the relative protein levels of Beclin 1, which interacts with HMGB1b, related to the total level of Beclin 1 in WCL, were quantified by ImageJ. Error bars indicate S.D. (n = 3); **, p < 0.01. F, HSP70 co-locates with Beclin 1. CIK cells were cotransfected with GFP-Beclin 1 and RFP-HSP70. Then the transfected cells were treated with rapamycin (Rap) or H2O2 for 24 h and subjected to confocal microscope observation. G, HSP70 interacts with Beclin 1. CIK cells were co-transfected with GFP-Beclin 1 and HSP70-HA for 16 h and then treated with or without rapamycin or H2O2 for 24 h. Co-IP was performed with anti-HA monoclonal Ab. Mouse IgG was used as a control. WCL was subjected to IB with anti-GFP, anti-HA, and anti-β-tubulin Abs, respectively.

Discussion

Over the past few years, scientists have attempted to understand the mechanisms of HMGB1 in mediating the cellular and biological responses (33). Some immune receptors, such as receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, and TLR9, have been indicated to interact with HMGB1 (33, 34). This study identified 31 HMGB1b-interacting proteins that were quantified by four or more peptides by LC-MS/MS upon GCRV infection. These proteins were functionally grouped into nucleus proteins, ribosomal proteins, metabolic proteins, growth-associated proteins, and HSP family proteins, which implies multiple functions of HMGB1b in cells. In line with a previous report that H2O2 or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimuli induce cytoplasmic HSP72 to translocate to the nucleus and interact with HMGB1 (10, 35), HSP70 is rapidly translocated to the nucleus upon H2O2 treatment in CIK cells, supporting a similar function in mammalian HSP72 and piscine HSP70 in response to oxidative stress. This result may be attributed to the high conservation between fish HSP70 and mammalian HSP72 (Fig. S1). Interestingly, mammalian HSP72 and piscine HSP70 show the opposite effect on the HMGB1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Mammalian HMGB1 functions as a proinflammatory cytokine in response to infection, injury, and stress, which is sufficient to initiate inflammation (10, 35, 36). However, inflammatory responses are strictly controlled by anti-inflammatory cytokines because excessive production of cytokines can lead to inflammatory diseases. Thus, HSP72, serving as an anti-inflammatory cytokine, inhibits ROS- or LPS-induced HMGB1 cytoplasmic translocation and release, which is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis. Here, ROS rarely induced nuclear export of HMGB1b but caused significant HMGB1b nucleocytoplasmic translocation upon HSP70 overexpression, which implies that HMGB1b is insufficient to sense oxidative stress. This result is consistent with our previous study that pathogenic stimulus-induced nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of grass carp HMGBs is not as intense as that in mammals (24). Therefore, we proposed that mammalian HMGB1 is more sensitive to stress than piscine HMGB1 and that piscine HSP70 is required for the activation of HMGB1b.

The autophagy lysosomal degradation pathway is one of the essential degradation systems in vertebrates and has been validated to play critical roles in cellular homeostasis, development, disease, and infection (2, 37). ROS are inducers of autophagy activation (4). Previous studies have uncovered molecular regulatory mechanisms between ROS and autophagy (4, 11, 12). Our experimental results first revealed that H2O2, a source of ROS, is sufficient to initiate autophagy and autophagy lysosomal flux in fish cells, which signifies that fish possess a mechanism to alleviate oxidative stress–induced damage via autophagy. Oxidative stress has been found to occur in various viral infections (38). ROS and antioxidant ingredients are a series of crucial signaling molecules in the oxidative stress response (4). GCRV infection induced the accumulation of ROS, enhancement of antioxidant genes, and autophagy activation in CIK cells, whereas NAC-induced ROS inhibition restricted autophagy activation. Given the vital role of H2O2 in autophagy activation, GCRV-induced accumulation of ROS may serve as a signaling molecule to initiate autophagy. Mild oxidative stress has been demonstrated to promote cell survival, whereas severe oxidative stress can cause oxidative injury and even death (38). So far, considerable advances have been made in understanding the complex interplay between autophagy and viruses (29, 39–42). On one hand, autophagy plays a positive role in the host antiviral response through the degradation of cytoplasmic viral components, activation of innate and adaptive immune signaling, promotion of cell survival, and cooperation between autophagy proteins and other immune pathways to restrict viral infections. On the other hand, viruses employ multiple strategies to avoid or antagonize the antiviral function of autophagy by avoiding autophagic capture and suppressing autophagy initiation and maturation (29). Furthermore, viruses exploit the autophagy pathway as a proviral system to keep virally infected cells alive and prolong viral replication (29). Therefore, it is urgent to understand the direct effects of oxidative stress and autophagy on GCRV infection. Our results demonstrate that rapamycin and nontoxic doses of H2O2 pretreatment promote cell survival and restrict GCRV replication, whereas autophagy the inhibitor 3-MA greatly increase viral productive infection. These data suggest that limited oxidative stress and autophagy are beneficial for the host against virus infection in grass carp, which is in contrast to a previous study in epithelioma papulosum cyprini cells (a cell line of cyprinid fish) that spring viremia of carp virus utilizes the autophagy pathway to facilitate its own genomic RNA replication (43). This distinction may be attributed to species and virus specificity. Therefore, this study opens a door for researchers to develop new antiviral drugs targeting ROS and autophagy regulation. More mechanistic investigation of oxidative stress–induced autophagy is essential for exploring therapeutic strategies and pathogenic insights into GCRV infection.

In mammals, abundant evidence emphasizes the subcellular localization–dependent roles of HMGB1 in autophagy modulation (12, 14, 44, 45). Especially upon ROS and starvation stimuli, HMGB1 translocates to cytoplasm, where it interacts with Beclin 1 and evokes the autophagic function of Beclin 1 by dissociating Bcl-2 from Beclin 1 (12, 31). Previously, dual roles of HSP70 in autophagy modulation have been reported: on one hand, HSP70 inhibits starvation-induced autophagy by regulating the mTOR/Akt pathway (19, 20). On the other hand, acetylated HSP70 binds to the Beclin 1–Vps34 complex and promotes KRAB-ZFP–associated protein 1 (KAP1)–dependent SUMOylation and activity of Vps34, which are essential for autophagic vesicle formation (30). Overexpression of HSP72 augments LPS-induced autophagy through c-Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation and Beclin 1 up-regulation (32). In this study, positive roles of HMGB1b and HSP70 in autophagy activation were verified by enhancement of the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and Beclin 1 level upon HMGB1b or HSP70 overexpression. HSP70 and HMGB1b also synergistically promoted autophagy activation. In the HMGB1–Beclin 1–mediated autophagy pathway, cysteines Cys-23 and Cys-45 in the box A domain in HMGB1 are required to interact with Beclin 1, and Cys-106 in the box B domain promotes cytosolic localization and sustained autophagy (12). Coincidentally, the three cysteines are conserved in grass carp HMGB1b (Fig. S3), which prompted us to explore whether cytoplasmic HMGB1b can promote autophagy like mammalian HMGB1. Interestingly, in HMGB1b-GFP stably transfected cells, H2O2 treatment induced a weak interaction between HMGB1b and Beclin 1, whereas HMGB1b–Beclin 1 association was enhanced by HSP70 overexpression but prevented by treatment with the HSP70 inhibitor VER-155008. Considering the foundation role of HSP70 in ROS-induced HMGB1b cytoplasmic translocation, this result further confirms the indispensable role of HSP70 in cytoplasmic HMGB1b-regulated autophagy. The direct interaction between HSP70 and Beclin 1 might be responsible for HMGB1b–Beclin 1 association. All of these findings uniformly add to the accumulating evidence of HSP70 in autophagic regulation.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that GCRV infection and H2O2 treatment induced the accumulation of ROS in CIK cells, which further enhanced autophagy activation. Nevertheless, ROS-induced autophagy, in turn, dramatically restricted GCRV replication. We clarified a novel mechanism for autophagy regulation: ROS induces HSP70 to translocate to the nucleus, where it interacts with HMGB1b, which results in HMGB1b cytoplasmic translocation and subsequent HMGB1b–Beclin 1 autophagic pathway activation. In the cytoplasm, HSP70 directly interacts with Beclin 1, which facilitates the association between HMGB1b and Beclin 1. These data provide credible evidence for the pivotal role of autophagy in antiviral defense and illuminate a new autophagic regulation mechanism in fish, which lays a foundation for further developing a more effective therapeutic strategy in the context of GCRV infection.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, viral infection, and reagents

CIK cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 units/ml penicillin (Sigma), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma). Cells were incubated at 28 °C with a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

GCRV-GZ1208, a type I GCRV strain, was kindly provided by Dr. Qing Wang. For viral infection, CIK cells were plated for 24 h in advance and then infected with GCRV-GZ1208 at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 0.1 as described previously (46).

Rabbit polyclonal Abs of LC3 and Beclin 1 were prepared by us. The anti-HA tag (ab18181) mouse mAb and anti-β-tubulin rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab6046) were purchased from Abcam. The anti-H3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (AH433) was purchased from Beyotime. The anti-GFP mouse mAb (CW0258A) was purchased from ComWin. The anti-HSP70 rabbit polyclonal antibody (BA0928) was purchased from Boster. The IRDye® 800CW donkey anti-rabbit IgG (926-32213) and anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (926-32212) secondary antibodies were purchased from LI-COR.

The DCFH-DA probe (E004) was purchased from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute. Rapamycin (R0395), 3-MA (M9281), and VER-155008 (SML0271) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. H2O2 (10011218) was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. NAC was purchased from Bestbio.

Plasmid construction and transfection

pHMGB1a-GFP and pHMGB1b-GFP were prepared as in our previous report (24). Based on the grass carp transcriptome, the complete open reading frames of LC3, HSP70, HSC70, Beclin 1, and lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) genes were amplified from cDNA derived from grass carp gills. For subcellular localizations, LC3 and Beclin 1 were introduced into pEGFP-C1, and HSP70, HSC70, Beclin 1, and LAMP2 were cloned into pDsRed2-C1. For overexpressing plasmids, HSP70-HA and HA-Beclin 1 were introduced into pcDNA3.1. The HA tag was introduced by corresponding primers (Table S2).

WB and co-IP analyses

Cytosol and nuclear proteins were extracted using cytosol/nuclear protein isolation kits (Beyotime). WB and co-IP experiments were conducted as in our previous study (46). IP of GFP fusion proteins was performed using GFP trap beads (Chromotek) that consist of a single-domain anti-GFP Ab conjugated to an agarose bead matrix. All results were obtained from three independent experiments.

TEM and confocal microscopy

To analyze the ultrastructures of autophagosomes and autolysosomes, CIK cells were treated with or without H2O2 or rapamycin or infected with GCRV in 6-well plates for 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h. Then the cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 1 h at room temperature. Ultrathin sections were prepared as described previously (6). Images were viewed on an HT-7700 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan).

For confocal microscopy, CIK cells were plated onto coverslips in 12-well plates and transfected with the indicated plasmids for 16 h, and the stably transfected cell lines were directly seeded in 12-well plates. Then the cells were treated with rapamycin or H2O2 or infected with GCRV for 24 h and 36 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed, fixed, and stained as reported previously (24). Finally, the samples were observed with a confocal microscope (SP8, Leica). GFP-LC3–labeled puncta were autophagosomes. In this study, cells with at least five GFP-LC3–positive puncta were regarded as autophagy activation (41).

qRT-PCR assay

Total cellular RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis were performed according to a previous report (22). qRT-PCR was established in the Roche LightCycler® 480 system, and EF1α was employed as an internal control gene for cDNA normalization. qRT-PCR amplification was carried out in a total volume of 15 μl containing 7.5 μl of BioEasy Master Mix (SYBR Green) (Hangzhou Bioer Technology Co., Ltd.), 5.1 μl of nuclease-free water, 2 μl of diluted cDNA (200 ng), and 0.2 μl of each gene-specific primer (10 μm) (Table S2). The data were analyzed as described previously (22, 46).

LC-MS/MS

GFP and HMGB1b-GFP stably transfected CIK cells were screened by G418 as reported previously (24). Cell lines stably expressing GFP and HMGB1b-GFP were seeded in 10-cm dishes and infected with GCRV for 24 h. Then the cells were collected for IP with GFP trap beads. The protein samples were eluted by SDT lysis. A portion of the IP samples was used to examine IP efficiency by WB with GFP Ab. LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). MS/MS spectra were searched using the MASCOT engine (Matrix Science) against the Actinopterygii UniProt sequence database and a grass carp transcriptome database in the NCBI SRA browser (Bioproject accession number SRP049081) (47).

Antiviral activity assay

To evaluate the antiviral activities of HMGB1b and HSP70, CIK cells were transfected with HMGB1b-GFP and HSP70-HA for 16 h and infected with GCRV at an m.o.i. of 0.1 for 36 h. The culture medium was collected as titer samples. To assess the influence of autophagy on GCRV replication, CIK cells were pretreated with or without 100 nm rapamycin, 5 mm 3-MA, and 0.15 mm H2O2 for 4 h and infected with GCRV. 36 h after GCRV infection, the supernatants were collected and filtered for titer samples. Virus titers in the supernatants were determined by standard plaque assay and the PFU method (48). Virus titer–induced cell viability was analyzed by MTT assay. In brief, approximately 1 × 104 CIK cells/well were seeded into a 96-well plate and cultured for 24 h. Then the medium was replaced with fresh medium supplemented with different titer samples, and the cells were incubated for 24 h. Then, 10 μl of MTT solution was added to the medium and incubated for another 4 h. Subsequently, 100 μl of formazan solution was added to each well. The optical density was observed at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

siRNA-mediated knockdown

Transient knockdown of endogenous HMGB1b and HSP70 in CIK cells was achieved by transfection of siRNA targeting HMGB1b and HSP70 mRNA, respectively. Three siRNA sequences (HMGB1b s1, GGAAGACAAUGUCUGCCAATT; HMGB1b s2, GGAGAGAAGAAGAGGCGAUTT; HMGB1b s3, GCAGCCCUAUGAGAAGAAATT; HSP70 s1, GCUGAUUGGCAGGAAGUUUTT; HSP70 s2, GGACAAGUCUCAGAUCCAUTT, HSP70 s3, CCAAUCAUCACUAAGCUUUTT) targeting different regions of each gene were synthesized by GenePharma (Jiangsu, China). The silencing efficiencies of the siRNA candidates were evaluated by qRT-PCR and compared with those in the negative control siRNA provided by the supplier. Our preliminary experiment indicated that s1 of HMGB1b and s1 of HSP70 possess the best silencing efficiency at a final concentration of 100 nm in mRNA levels. For WB, the LGP2-FLAG overexpression CIK cell line was plated in 6-well plates and transfected with s3 using FuGENE 6. The subsequent experiments were performed with s1 of HMGB1b and HSP70, respectively. For WB analysis, CIK cells were seeded in 6-well plates for 24 h. The cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA for 16 h and treated with H2O2 for another 24 h. Then the cells were lysed for WB analysis.

Author contributions

Y. R. and J. S. conceptualization; Y. R. and Z. L. data curation; Y. R. validation; Y. R. and Q. W. investigation; Y. R. visualization; Y. R., Q. W., and C. Y. methodology; Y. R. writing-original draft; Y. R., Z. L., and J. S. writing-review and editing; C. Y. formal analysis; L. L. resources; J. S. supervision; J. S. project administration; H. S. and X. X. data analysis; J. J. performance of the experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. Pinghui Feng (University of Southern California) for critical proofreading and editing and Dr. Qing Wang (Pearl River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Guangzhou, China) for kindly providing the GCRV-GZ1208 strain. We also thank Dr. Xiaoling Liu, Dr. Gailing Yuan, and Dr. Jiagang Tu for helpful discussions and Dr. Nan Chen and Yao Wang for material assistance.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572648) and the Huazhong Agricultural University Scientific and Technological Self-innovation Foundation (2014RC019). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3 and Tables S1 and S2.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- HSP

- heat shock protein

- GCRV

- grass carp reovirus

- HMGB1

- high-mobility group box

- CIK

- Ctenopharyngodon idella kidney

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- WB

- Western blot

- Ab

- antibody

- TEM

- transmission electron microscopy

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase

- CAT

- catalase

- GSS

- glutathione synthetase

- NAC

- N-acetyl-l-cysteine

- 3-MA

- 3-methladenine

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- cDNA

- complementary DNA

- WCL

- whole-cell lysate

- IB

- immunoblot

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein

- DCFH-DA

- dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time RT-PCR

- PFU

- plaque-forming unit.

References

- 1. Mizushima N., Levine B., Cuervo A. M., and Klionsky D. J. (2008) Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451, 1069–1075 10.1038/nature06639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levine B., and Kroemer G. (2008) Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132, 27–42 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong P. M., Puente C., Ganley I. G., and Jiang X. (2013) The ULK1 complex: sensing nutrient signals for autophagy activation. Autophagy 9, 124–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li L., Tan J., Miao Y., Lei P., and Zhang Q. (2015) ROS and autophagy: interactions and molecular regulatory mechanisms. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 35, 615–621 10.1007/s10571-015-0166-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhu L., Huang G., Sheng J., Fu Q., and Chen A. (2016) High-mobility group box 1 induces neuron autophagy in a rat spinal root avulsion model. Neuroscience 315, 286–295 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He R., Peng J., Yuan P., Xu F., and Wei W. (2015) Divergent roles of BECN1 in LC3 lipidation and autophagosomal function. Autophagy 11, 740–747 10.1080/15548627.2015.1034404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu X. H., Wang Z. J., Chen D. M., Chen M. F., Jin X. X., Huang J., and Zhang Y. G. (2016) Molecular characterization of Beclin 1 in rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) and its expression after waterborne cadmium exposure. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 42, 111–123 10.1007/s10695-015-0122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scaffidi P., Misteli T., and Bianchi M. E. (2002) Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 418, 191–195 10.1038/nature00858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rao Y., and Su J. (2015) Insights into the antiviral immunity against grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) reovirus (GCRV) in grass carp. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 670437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang D., Kang R., Xiao W., Jiang L., Liu M., Shi Y., Wang K., Wang H., and Xiao X. (2007) Nuclear heat shock protein 72 as a negative regulator of oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide)-induced HMGB1 cytoplasmic translocation and release. J. Immunol. 178, 7376–7384 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu Y., Tang D., and Kang R. (2015) Oxidative stress-mediated HMGB1 biology. Front. Physiol. 6, 93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tang D., Kang R., Livesey K. M., Cheh C. W., Farkas A., Loughran P., Hoppe G., Bianchi M. E., Tracey K. J., Zeh H. J. 3rd, Lotze M. T. (2010) Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 190, 881–892 10.1083/jcb.200911078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun X., and Tang D. (2014) HMGB1-dependent and -independent autophagy. Autophagy 10, 1873–1876 10.4161/auto.32184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu K., Huang J., Xie M., Yu Y., Zhu S., Kang R., Cao L., Tang D., and Duan X. (2014) MIR34A regulates autophagy and apoptosis by targeting HMGB1 in the retinoblastoma cell. Autophagy 10, 442–452 10.4161/auto.27418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang R., Livesey K. M., Zeh H. J. 3rd, Lotze M. T., and Tang D. (2011) Metabolic regulation by HMGB1-mediated autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy 7, 1256–1258 10.4161/auto.7.10.16753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li Y., Kang X., and Wang Q. (2011) HSP70 decreases receptor-dependent phosphorylation of Smad2 and blocks TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Genet. Genomics 38, 111–116 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lahaye X., Vidy A., Fouquet B., and Blondel D. (2012) Hsp70 protein positively regulates rabies virus infection. J. Virol. 86, 4743–4751 10.1128/JVI.06501-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taguwa S., Maringer K., Li X., Bernal-Rubio D., Rauch J. N., Gestwicki J. E., Andino R., Fernandez-Sesma A., and Frydman J. (2015) Defining Hsp70 subnetworks in dengue virus replication reveals key vulnerability in flavivirus infection. Cell 163, 1108–1123 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dokladny K., Zuhl M. N., Mandell M., Bhattacharya D., Schneider S., Deretic V., and Moseley P. L. (2013) Regulatory coordination between two major intracellular homeostatic systems: heat shock response and autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 14959–14972 10.1074/jbc.M113.462408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dokladny K., Myers O. B., and Moseley P. L. (2015) Heat shock response and autophagy: cooperation and control. Autophagy 11, 200–213 10.1080/15548627.2015.1009776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang C., Peng L., and Su J. (2013) Two HMGB1 genes from grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella mediate immune responses to viral/bacterial PAMPs and GCRV challenge. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 39, 133–146 10.1016/j.dci.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rao Y., Su J., Yang C., Peng L., Feng X., and Li Q. (2013) Characterizations of two grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella HMGB2 genes and potential roles in innate immunity. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 41, 164–177 10.1016/j.dci.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang C., Chen L., Su J., Feng X., and Rao Y. (2013) Two novel homologs of high mobility group box 3 gene in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella): potential roles in innate immune responses. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 35, 1501–1510 10.1016/j.fsi.2013.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rao Y., Su J., Yang C., Yan N., Chen X., and Feng X. (2015) Dynamic localization and the associated translocation mechanism of HMGBs in response to GCRV challenge in CIK cells. Cell Mol. Immunol. 12, 342–353 10.1038/cmi.2014.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhong L., Shu W., Dai W., Gao B., and Xiong S. (2017) Reactive oxygen species-mediated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation contributes to hepatitis B virus X protein-induced autophagy via regulation of the Beclin-1/Bcl-2 interaction. J. Virol. 91, e00001–00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Navarro-Yepes J., Burns M., Anandhan A., Khalimonchuk O., del Razo L. M., Quintanilla-Vega B., Pappa A., Panayiotidis M. I., and Franco R. (2014) Oxidative stress, redox signaling, and autophagy: cell death versus survival. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 66–85 10.1089/ars.2014.5837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kabeya Y., Mizushima N., Ueno T., Yamamoto A., Kirisako T., Noda T., Kominami E., Ohsumi Y., and Yoshimori T. (2000) LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 19, 5720–5728 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vriend J., and Reiter R. J. (2015) The Keap1-Nrf2-antioxidant response element pathway: a review of its regulation by melatonin and the proteasome. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 401, 213–220 10.1016/j.mce.2014.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dong X., and Levine B. (2013) Autophagy and viruses: adversaries or allies? J. Innate Immun. 5, 480–493 10.1159/000346388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang Y., Fiskus W., Yong B., Atadja P., Takahashi Y., Pandita T. K., Wang H. G., and Bhalla K. N. (2013) Acetylated hsp70 and KAP1-mediated Vps34 SUMOylation is required for autophagosome creation in autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 6841–6846 10.1073/pnas.1217692110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kang R., Livesey K. M., Zeh H. J., Loze M. T., and Tang D. (2010) HMGB1-A novel Beclin 1-binding protein active in autophagy. Autophagy 6, 1209–1211 10.4161/auto.6.8.13651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li S., Zhou Y., Fan J., Cao S., Cao T., Huang F., Zhuang S., Wang Y., Yu X., and Mao H. (2011) Heat shock protein 72 enhances autophagy as a protective mechanism in lipopolysaccharide-induced peritonitis in rats. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 2822–2834 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang H., Hreggvidsdottir H. S., Palmblad K., Wang H., Ochani M., Li J., Lu B., Chavan S., Rosas-Ballina M., Al-Abed Y., Akira S., Bierhaus A., Erlandsson-Harris H., Andersson U., and Tracey K. J. (2010) A critical cysteine is required for HMGB1 binding to Toll-like receptor 4 and activation of macrophage cytokine release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11942–11947 10.1073/pnas.1003893107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tian J., Avalos A. M., Mao S. Y., Chen B., Senthil K., Wu H., Parroche P., Drabic S., Golenbock D., Sirois C., Hua J., An L. L., Audoly L., La Rosa G., Bierhaus A., et al. (2007) Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat. Immunol. 8, 487–496 10.1038/ni1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tang D., Kang R., Xiao W., Wang H., Calderwood S. K., and Xiao X. (2007) The anti-inflammatory effects of heat shock protein 72 involve inhibition of high-mobility-group box 1 release and proinflammatory function in macrophages. J. Immunol. 179, 1236–1244 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang H., and Tracey K. J. (2010) Targeting HMGB1 in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 149–156 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Varga M., Fodor E., and Vellai T. (2015) Autophagy in zebrafish. Methods 75, 172–180 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reshi M. L., Su Y. C., and Hong J. R. (2014) RNA viruses: ROS-mediated cell death. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 467452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delorme-Axford E., Bayer A., Sadovsky Y., and Coyne C. (2013) Autophagy as a mechanism of antiviral defense at the maternal–fetal interface. Autophagy 9, 2173–2174 10.4161/auto.26558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kobayashi S., Orba Y., Yamaguchi H., Takahashi K., Sasaki M., Hasebe R., Kimura T., and Sawa H. (2014) Autophagy inhibits viral genome replication and gene expression stages in West Nile virus infection. Virus Res. 191, 83–91 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moy R. H., Gold B., Molleston J. M., Schad V., Yanger K., Salzano M. V., Yagi Y., Fitzgerald K. A., Stanger B. Z., Soldan S. S., and Cherry S. (2014) Antiviral autophagy restricts rift valley fever virus infection and is conserved from flies to mammals. Immunity 40, 51–65 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sharma M., Bhattacharyya S., Nain M., Kaur M., Sood V., Gupta V., Khasa R., Abdin M. Z., Vrati S., and Kalia M. (2014) Japanese encephalitis virus replication is negatively regulated by autophagy and occurs on LC3-I- and EDEM1-containing membranes. Autophagy 10, 1637–1651 10.4161/auto.29455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu L., Zhu B., Wu S., Lin L., Liu G., Zhou Y., Wang W., Asim M., Yuan J., Li L., Wang M., Lu Y., Wang H., Cao J., and Liu X. (2015) Spring viraemia of carp virus induces autophagy for necessary viral replication. Cell Microbiol. 17, 595–605 10.1111/cmi.12387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tang D., Kang R., Livesey K. M., Kroemer G., Billiar T. R., Van Houten B., Zeh H. J. 3rd, and Lotze M. T. (2011) High-mobility group box 1 is essential for mitochondrial quality control. Cell Metab. 13, 701–711 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tang D., Kang R., Cheh C. W., Livesey K. M., Liang X., Schapiro N. E., Benschop R., Sparvero L. J., Amoscato A. A., Tracey K. J., Zeh H. J., and Lotze M. T. (2010) HMGB1 release and redox regulates autophagy and apoptosis in cancer cells. Oncogene 29, 5299–5310 10.1038/onc.2010.261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rao Y., Wan Q., Yang C., and Su J. (2017) Grass carp laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 serves as a negative regulator in retinoic acid-inducible gene I- and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-mediated antiviral signaling in resting state and early stage of grass carp reovirus infection. Front. Immunol. 8, 352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wan Q., and Su J. (2015) Transcriptome analysis provides insights into the regulatory function of alternative splicing in antiviral immunity in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Sci. Rep. 5, 12946 10.1038/srep12946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen L., Su J., Yang C., Peng L., Wan Q., and Wang L. (2012) Functional characterizations of RIG-I to GCRV and viral/bacterial PAMPs in grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella. PLoS ONE 7, e42182 10.1371/journal.pone.0042182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.