Abstract

We present a case of a 21-year-old Caucasian woman at 27 weeks of pregnancy who was admitted to the obstetric department for pre-term labor. She received 10 mg of nifedipine 4 times in 1 h, according to the internal protocol. Shortly after, she brutally deteriorated with pulmonary edema and hypoxemia requiring transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) for mechanical ventilation. She finally improved and was successfully extubated after undergoing a percutaneous valvuloplasty of the mitral valve. This case illustrates a severe cardiogenic shock after administration of nifedipine for premature labor in a context of unknown rheumatic mitral stenosis. Nifedipine induces a reflex tachycardia that reduces the diastolic period and thereby precipitates pulmonary edema in case of mitral stenosis. This case emphasizes the fact that this drug may be severely harmful and should never be used before a careful physical examination and echocardiography if valvular heart disease is suspected.

Key words: nifedipine, pregnancy, mitral stenosis, pulmonary edema

Introduction

Nifedipine is a calcium-channel blocker that has been used as tocolytic agent for decades. This medication blocks the influx of calcium through the cell membrane, inhibits the release of intracellular calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and enhances calcium efflux from the cell. The resulting low intracellular concentration inhibits the myosin light-chain kinase phosphorylation, leading to myometrial relaxation. Calcium-channel blockers, specially nifedipine, have been proven to be more effective in prolonging pregnancy with fewer secondary effects than betamimetics.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] Maternal serious adverse events have been described in case reports.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11] We present the case of a 21-year-old woman who developed a severe cardiogenic choc after the administration of nifedipine.

Case Report

A 21-year-old Caucasian woman at 27 weeks of pregnancy was admitted to the obstetric department for pre-term labor. She received 10 mg of nifedipine 4 times in 1 h, according to the internal protocol. Shortly after, she brutally deteriorated with pulmonary edema and hypoxemia requiring transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU).

At the admission in the ICU, her blood pressure was 101/61 mm Hg (MAP = 72), ECG revealed a sinus tachycardia (142 bpm), and oxygen saturation was 98% under 100% high flow oxygenation. Physical examination revealed a loud first heart sound, diastolic murmur, bilateral wheezing, and jugular venous distension.

The clinical situation rapidly deteriorated with a fall in systolic blood pressure and a worsening desaturation (78%) with metabolic acidosis and hyperlactatemia (34 mg/dL). The patient was intubated and ventilated (volume-controlled ventilation with FiO2 100% and PEEP at 15 cm of H2O). Chest X-ray confirmed pulmonary edema.

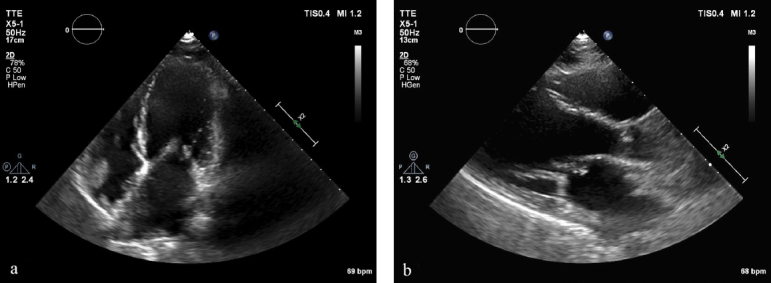

Cardiac echography revealed unknown severe mitral stenosis (Figure 1a and b) with normal left ventricular function, enlargement and pressure overload of the left atrium, and severe pulmonary hypertension [estimated pulmonary systolic arterial pressure (PAP) = 85 mm Hg].

Figure 1.

Echocardiography before valvulosplasty. (a) Apical view and (b) paravalvular view

The diagnosis was a cardiogenic shock precipitated by administration of nifedipine in a pregnant woman with unknown severe mitral stenosis.

Loop diuretics (furosemide) and full-dose heparin were administered once blood pressure was stabilized. Ultrasound examination showed no fetal distress. Transoesophageal echocardiography showed a severe rheumatic mitral stenosis with an estimated valve area of 0.5 cm2 and a transmitral mean gradient of 25 mm Hg. The Wilkins score was 8, authorizing percutaneous valvuloplasty.[12]

However, soon after admission, spontaneous vaginal delivery occurred, before the valvuloplasty start.

The baby was alive and transferred to intensive neonatal care unit. The mother remained in a critical state with hypotension and needed ventilation despite the delivery.

Even more, the delivery was complicated by an endometritis with sepsis treated by ceftriaxone and ampicillin, so that valvuloplasty had to be postponed.

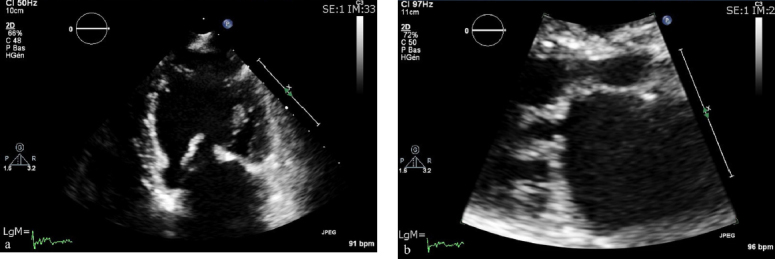

On day 8, after resolution of the infection, a percutaneous double balloon mitral valvuloplasty was performed with a good result (Figures 2 and 3). Mitral mean gradient was reduced from 10 to 3 mmHg, the mitral area was increased from 0.5 to 1.65 cm2, and pulmonary pressure was normalized (Figure 4a and b).

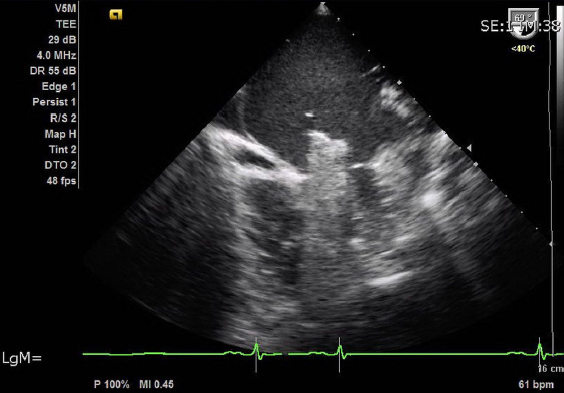

Figure 2.

Echocardiography during procedure: Insertion of double balloon

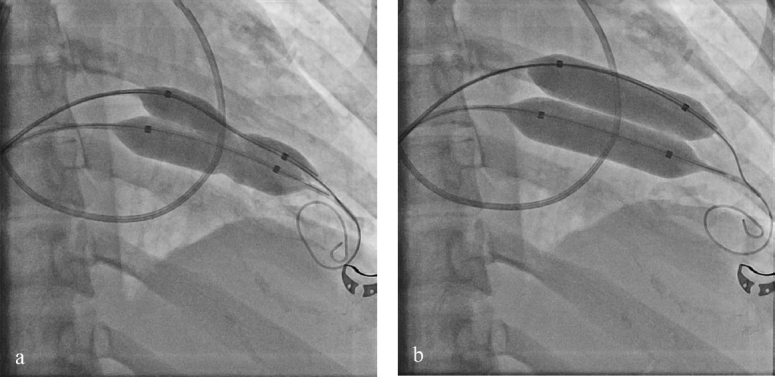

Figure 3.

Angiography of the double balloon during valvuloplasty. (a) Deflated balloon insertion before valvuloplasty and (b) dilated balloon.

Figure 4.

Echocardiography after valvulosplasty. (a): Apical view and (b) parasternal view

After valvuloplasty, the recovery was rapid and the patient could be extubated the day after.

Discussion

Tocolytics are frequently used to delay delivery. Because of limited available data, there is no recommendations or guidelines regarding the use of maternal tocolytics aimed at improving outcomes of the babies.[13, 14] When tocolysis is required (for in utero transfer or pulmonary maturation), nifedipine is the drug of choice.[14] But nowadays nifedipine is not approved by the FDA for tocolytic use. Today, the use is based on studies with insufficient data about safety.[15, 16] Hemodynamic effects are variable in the literature. Luewan et al. found 17.8% and 17.2% of systolic and diastolic hypotension, respectively (fall of 15 mm Hg or more). In 3.2% of woman, they found systolic blood pressure under 90 mm Hg, and 3.8% had a diastolic blood pressure under 60 mm Hg. [6] Yamasato et al. observed tachycardia in 37.3% at 20–60 min after intake. [7]

In the literature evaluated by Khan et al., there was no maternal death but 85 of the fetal death attributed to the use of calcium-channel blocker, whereas 51% were associated with nifedipine.[16] Maternal serious adverse event are reported in case reports.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, ] Some authors think that they are underreported for medicolegal reasons because of the use of a non-licensed drug.[17]

During pregnancy, there is an augmentation of the intravascular volume, a fall of the peripheral resistance, a rise of cardiac output, a relative anemia, and an increase in oxygen consumption. Caution in the use of calcium-channel blocker is recommended when cardiovascular condition is compromised such as in twin pregnancy, intra uterine infection, maternal hypertension, or cardiac disease.[18] Cardiovascular disease is present in 1–3% of all pregnancies and is responsible for 10–15% of overall maternal mortality.[19] Of which, 80% are valvular diseases. In industrialized countries, congenital heart disease is the main etiology for valvular heart disease, whereas in developing countries, rheumatic valvular disease remains the leading cause.[20] In many patients with significant valvular heart disease, the diagnosis is unknown before pregnancy and the pathology is revealed by the hemodynamic burden of pregnancy.[21] In mitral stenosis, heart failure occurs frequently in the second and third trimesters in previously asymptomatic patients. The rate of prematurity is 20–30% and rate of stillbirth is 1–3%.[22] The treatment of choice during pregnancy is percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty, with fewer fetal complications when compared to surgery[23] and an improvement in the New York Heart Association (NYHA) status by at least one class in 80% of the cases.[24, 25] The average estimated radiation energy for balloon mitral valvuloplasty is 0.2 rad, which is far lower than the 5-rad level under which radiation is considered to be safe.[26] The indication for balloon mitral valvuloplasty during pregnancy is a patient with a refractory heart failure, a mild mitral regurgitation, a suitable morphology, and the absence of left atrial thrombus.[23] Nitric oxide is only a measure to buy time in order to realize in better conditions the balloon mitral valvulosplasty.[27, 28]

In our patient, cardiogenic shock was precipitated by nifedipine, which induced hypotension and reflex tachycardia. Tachycardia and vasodilatation are very harmful in mitral stenosis.

Conclusion

We present a case of a 21-year-old pregnant woman who developed a severe cardiogenic shock after the administration of nifedipine for premature labor in the context of unknown rheumatic mitral stenosis. This case emphasizes the fact that this drug may be severely harmful and should never be used before a careful physical examination and echocardiography if valvular heart disease is suspected.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.King JF, Flenady V, Papatsonis D, Dekker G, Carbonne B. Calcium channel blockers for inhibiting preterm labor, a systematic review of the evidence and a protocol for administration of nifedipine. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43:192. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8666.2003.00074.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weerakul W, Chittacharoen A, Suthutvoravut S. Nifedipine versus terbutaline in management of preterm labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;76:311. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00547-1. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papatsonis DN, Van Geijn HP, Adèr HJ, Lange FM, Bleker OP, Dekker GA. Nifedipine and Ritodrine in the management of preterm labor: a randomized multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:230. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00182-8. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cararach V, Palacio M, Martínez S, Deulofeu P, Sánchez M, Cobo T. Comparison of their efficacy and secondary effects. Nifedipine versus ritodrine for suppression of preterm labor. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;127:204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.10.020. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bracero LA, Leikin E, Kirshenbaum N, Tejani N. Comparison of nifedipine and ritodrine for the treatment of preterm labor. Am J Perinatol. 1991;8:365. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999417. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luewan S, Mahatep R, Tongsong T. Hypotension in normotensive pregnant women treated with nifedipine as a tocolytic drug. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:527. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1674-z. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamasato K, Burlingame J, Kaneshiro B. Hemodynamic effects of nifedipine tocolysis. Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:17. doi: 10.1111/jog.12478. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vast P, Dubreucq-Fossaert S, Subtil D. Acute pulmonary oedema during nicardipine therapy for premature labour. Report of five cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;113:98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.05.004. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bal L, Thierry S, Brocas E, Adam M, Van de Louw A, Tenaillon A. Pulmonary oedema induced by calcium-channel blockade for tocolysis. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:910. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000135182.79774.A0. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oei SG, Oei SK, Brolmann H. Myocardial infarction during nifedipine therapy for preterm labor. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:154. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verhaert D, Van Acker R. Acute myocardial infarction during pregnancy. Acta Cardiol. 2004;59:331. doi: 10.2143/AC.59.3.2005191. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkins GT, Weyman AE, Abascal VM, Block PC, Palacios IF. Percutaneous balloon dilatation of the mitral valve: an analysis of echocardiographic variables related to outcome and the mechanism of dilatation. Br Heart J. 1988;60:299. doi: 10.1136/hrt.60.4.299. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2015. 2018. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/preterm-birth-guideline Available at. Accessed on August 23. [PubMed]

- 14.Vogel JP, Oladapo OT, Manu A, Gülmezoglu AM, Bahl R. New WHO recommendations to improve the outcomes of preterm birth. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e589. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00183-7. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamont RF, Khan KS, Beattie B, Cabero Roura L, Di Renzo GC, Dudenhausen JW. The quality of nifedipine studies used to assess tocolytic efficacy: a systematic review. J Perinatol Med. 2005;33:287. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2005.055. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan K, Zamora J, Lamont RF, Van Geijn Hp H, Svare J, Santos-Jorge C. Safety concerns for the use of calcium channel blockers in pregnancy for the treatment of spontaneous preterm labour and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:1030. doi: 10.3109/14767050903572182. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beattie R, Hlmer H, Van Geijn H. Emerging issues over the choice of nifedipine, beta agonists and atosiban for tocolysis in spontaneous preterm labour-a proposed systematic review by the international preterm labor council. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:213. doi: 10.1080/01443610410001660643. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Geijn, Lenglet J, Bolte A. Nifedipine trials: effectiveness and safety aspect. BJOG. 2005;112:S79. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00591.x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suchaya L, Rathasart M, Theera T. Hypotension in normotensive pregnant women treated with nifedipine as tocolytic drug. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:527. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1674-z. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samiei N, Amirsardari M, Rezaei Y, Parsaee M, Kashfi F, Hantoosh Zadeh S. Echocardiographic Evaluation of Hemodynamic Changes in Left-Sided Heart Valves in Pregnant Women With Valvular Heart Disease. Am J Cardio. 2016;118:1046. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.07.005. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthony J, Osman O, Sani MU. Valvular heart disease in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016;27:111. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-052. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanna M, Stergiopoulos K. Pregnancy complicated by valvular heart disease: an update. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:1. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000712. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Souza JA, Martinez EE Jr, Ambrose JA, Alves CM, Born D, Buffolo E. Percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty in comparison with open mitral valve commissurotomy for mitral stenosis during pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01184-0. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinayakumar D, Vinod GV, Madhavan S, Krishnan MN. Maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnant women undergoing balloon mitral valvotomy for rheumatic mitral stenosis. Indian Heart J. 2016;68:780. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2016.04.017. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Andrade J, Maldonado M, de Souza J. The role of mitral balloon valvuloplasty in the treatment of rheumatic mitral valve stenosis during pregnancy. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2001;54:573. doi: 10.1016/s0300-8932(01)76359-2. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Routray SN, Mishra TK, Swain S, Patnaik UK, Behera M. Balloon mitral valvuloplasty during pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;85:18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.09.005. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juul N.. Inhaled nitric oxide in a pregnant woman with pulmonary hypertension and critical aortic and mitral stenosis. Chest. 2014;145:S509a. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahoney P, Loh E, Herrmann H. Hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide in women with mitral stenosis and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:188. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01314-x. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]