Abstract

There have been recent advances in stroke prevention in nutrition, blood pressure control, antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation, identification of high-risk asymptomatic carotid stenosis, and percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale. There is evidence that the Mediterranean diet significantly reduces the risk of stroke and that B vitamins lower homocysteine, thus preventing stroke. The benefit of B vitamins to lower homocysteine was masked by harm from cyanocobalamin among study participants with impaired renal function; we should be using methylcobalamin instead of cyanocobalamin. Blood pressure control can be markedly improved by individualized therapy based on phenotyping by plasma renin and aldosterone. Loss of function mutations of CYP2D19 impair activation of clopidogrel and limits its efficacy; ticagrelor can avoid this problem. New oral anticoagulants that are not significantly more likely than aspirin to cause severe bleeding, and prolonged monitoring for atrial fibrillation (AF), have revolutionized the prevention of cardioembolic stroke. Most patients (~90%) with asymptomatic carotid stenosis are better treated with intensive medical therapy; the few that could benefit from stenting or endarterectomy can be identified by a number of approaches, the best validated of which is transcranial Doppler (TCD) embolus detection. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale has been shown to be efficacious but should only be implemented in selected patients; they can be identified by clinical clues to paradoxical embolism and by TCD estimation of shunt grade. “Treating arteries instead of treating risk factors,” and recent findings related to the intestinal microbiome and atherosclerosis point the way to promising advances in future.

Key words: stroke prevention, nutrition, antiplatelet, anticoagulant, hypertension, patent foramen ovale, carotid stenosis

In recent years, there have been advances in stroke prevention in relation to nutrition, blood pressure control, antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation, identification of high-risk asymptomatic carotid stenosis, and percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale. These will be discussed, as will two issues that may lead to future advances in stroke prevention: a paradigm change to “treating arteries instead of treating risk factors,” and recent findings related to the intestinal microbiome and atherosclerosis.

Nutrition

In the field of nutrition, several advances have been made. There is better evidence that the Mediterranean diet prevents stroke, and it is now understood that B vitamins lower homocysteine, thus preventing stroke. Recent understanding of the importance of the intestinal microbiome also provides a new perspective on diet.

Mediterranean diet

Lifestyle, and in particular diet, is much more important in stroke prevention than most physicians suppose. I have recently reviewed diet for stroke prevention.[1] Recently, there has been unwarranted controversy about the harm of cholesterol and saturated fat, arising from the recognition that a low-fat diet that is high in sugar and carbohydrates is not the best way to prevent vascular disease. As pointed out by Willett and Stampfer, the low-fat diet that was thought for many years to be the best diet for vascular prevention was never shown to be beneficial; it was pulled from thin air by a committee trying to imagine a diet that would lower fasting cholesterol levels.[2] It was discovered in the Seven Countries Study that the risk of coronary mortality in Crete was 1/15th of what it was in Finland and only 40% of that in Japan. In Finland, 38% of calories were from fat, but it was mostly animal fat, high in saturated fat and accompanied by a high cholesterol intake. In Crete, 40% of calories were from fat, but it was mainly olive oil. So it is not the amount of fat but the kind of fat that matters. [2]

The Cretan Mediterranean diet is a high-fat/low glycemic index diet that was described by Ancel Keys, the head of the Seven Countries Study, as a “mainly vegetarian diet, … favoring fruit for dessert” and “lower in meat and dairy” than a Western diet.[3]

The hypothesis that it is possible that a vegan or strictly vegetarian diet may be as beneficial as the Mediterranean diet has not been tested. What is clear is that compared to a low-fat diet or a low-carbohydrate diet, the Mediterranean diet was the best for lowering fasting blood glucose, fasting insulin, and insulin resistance among diabetic participants in a landmark study in Israel. Weight loss was better and equally good on the Mediterranean and low-carbohydrate diet.[4]

In the Lyon Diet Heart Study, in survivors of myocardial infarction, cardiovascular events were reduced by more than 70% in 4 years with the Mediterranean diet compared to a “prudent Western diet.”[5] This was more than twice the effect of simvastatin in secondary prevention in the contemporaneous Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study, which reported a 40% reduction of recurrent myocardial infarction in 6 years.[6]

The Spanish study of a Mediterranean diet versus a low-fat diet in primary prevention reported a 30% reduction of cardiovascular events with the Mediterranean diet.[7] In the arm of that study that was fortified with mixed nuts, the reduction of stroke was 47% in 5 years.

On the basis of the best evidence to date, the best diet for stroke prevention is a Mediterranean diet, which is high in beneficial oils, fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes and low in cholesterol and saturated fat. Table 1 outlines the diet that I recommend to my patients.

Table 1.

Dietary recommendations for patients at risk of stroke

| • No egg yolks: use egg whites or substitutes such as Egg Beaters®, Egg Creations® |

| • Flesh of any animal: one palm size portion or less, approximately every other day (or half that daily) |

| • Seldom red meat, mainly fish and chicken |

| • High intake of olive oil, Canola oil |

| • Only whole grains |

| • High intake of vegetables, fruit, legumes |

| • Avoid deep fried foods, hydrogenated oils (trans fats) |

| • Avoid sugar and refined grains, and limit potatoes |

To accomplish this, patients need to think of their meatless day not as a punishment day but as a gourmet cooking class day: “Having fun learning how to make healthy eating tasty.”[57] (Reproduced by permission of BMJ from: Spence JD. Diet for stroke prevention. Stroke and Vascular Neurology 2018;0:e000130. doi:10.1136/svn-2017-000130)

B vitamins for lowering of homocysteine

There is a widespread belief that B vitamins that lower homocysteine do not prevent stroke. This is probably due to the harm from cyanocobalamin among participants with impaired renal function, cancelling out the benefit among participants with good renal function. It is now clear that B vitamins do prevent stroke, but we should be using methylcobalamin instead of cyanocobalamin. I have recently reviewed the history of this issue[8]; the evidence is summarized in Table 2. This was shown in meta-analysis stratified by renal function and dose of cyanocobalamin[9] and analysis of patient-level data[9] from the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) trial[10] and the Vitamins to Prevent Stroke (VITATOPS) trial.[11]

Table 2.

Summary of the evidence supporting B vitamins for stroke prevention

| VISP[10] including all patients showed no benefit, nor did NORVIT[58]—both older populations with poorer renal function than in later major trials, receiving cyanocobalamin. In NORVIT, there was an increased risk of stroke among persons receiving cyanocobalamin. |

| In HOPE-2[59] (younger healthier population with better renal function than in NORVIT and VISP), B vitamins reduced the risk of stroke by 23%. |

| In SuFolOM3[60] (younger participants than in the other trials, with the best renal function of the studies and only 20 μg of cyanocobalamin), B vitamins reduced stroke by 43%. |

| In the VISP subgroup analysis[61] excluding patients with eGFR <46.18 and those who got B12 shots, a 34% reduction in the composite outcome of stroke/MI/vascular death was observed, comparing high-dose vitamin in patients with good vitamin B12 absorption vs. low-dose vitamin in patients with poor vitamin B12 absorption (baseline vitamin B12 below the median). |

| B vitamins including 1000 μg of cyanocobalamin were harmful in patients with diabetic nephropathy (DIVINe study),[62] accelerating decline in renal function and doubling cardiovascular events. |

| In VITATOPS, B vitamins with only 400 μg of cyanocobalamin were not beneficial in diabetics with eGFR <50 (HR = 0.88; 95% CI = 0.59,1.32; P= 0.54) but were beneficial in patients with eGFR >50 (HR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.68, 0.98; P = 0.03)[9] If the harm from B vitamins in DIVINe were from folic acid, then there should have been harm among patients in the Chinese CSPPT trial[63] with impaired renal function and folic acid alone; instead folic acid improved renal function and reduced a composite event including overall mortality[64]; therefore, the harm in the other studies was due to either cyanocobalamin or vitamin B6. |

| Koyama’s work (increased cyanide levels in renal failure[65] and benefit of methylcobalamin not shown in the WENBIT study[66] with cyanocobalamin),[67] plus 2 plausible mechanisms for harm (thiocyanate increases LDL oxidation[68] and formation of thiocyanate consumes H2S), points to the cyanide in cyanocobalamin (or impaired decyanation of cyanocobalamin) in patients with impaired renal function as the likely problem. |

| Essentially, the null trials are explained by harm in participants with impaired renal function cancelling out the benefit among participants with good renal function.[9] |

(Reproduced by permission of Lancet Neurology from: Spence JD, Yi Q, Hankey GJ. B vitamins in stroke prevention: time to reconsider. Lancet Neurol. 2017 Sep;16(9):750-60.)

Intestinal microbiome and diet

The importance of the intestinal microbiome in health and disease is increasingly recognized, as is the interaction between diet and the intestinal microbiome.[12] Nutrients are fermented by the intestinal bacteria to a large range of metabolic products. Many of these are renally eliminated, so patients with renal impairment have high plasma levels of the metabolites. Phosphatidylcholine (largely from egg yolk) and carnitine (largely from red meat) are converted by the intestinal bacteria to trimethylamine, which in turn is oxidized in the liver to trimethylamine n-oxide (TMAO). Plasma levels of TMAO are high in patients with renal failure and contribute both to acceleration of the decline in renal function and to the very high cardiovascular risk of patients with renal failure.[13] In patients referred for coronary angiography, TMAO levels in the top quartile after a test dose of two hard-boiled eggs were associated with a 2.5-fold increase in the 3-year risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, or vascular death.[14] A number of other metabolites are produced from amino acids derived largely from animal protein.

Intestinal metabolites including indoxyl sulfate, indole 3-acetic acid, p-cresyl sulfate, p-cresyl glucuronide and phenylacetylglutamine are also implicated in mediating cardiovascular disease in patients with renal impairment. [15,16,17,18]

Plasma levels of indoxyl sulfate (IS) and p-cresyl sulfate (PCS) are 54 and 17 times higher in patients with renal failure. [19] Indoxyl sulfate and indole 3-acetic acid, produced from tryptophan, promote endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress [20] and are associated with cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing hemodialysis. [15,21] Patients with severe atherosclerosis not explained by traditional risk factors (unexplained atherosclerosis) have higher plasma levels of the toxic metabolites of the intestinal microbiome, and patients with unexplained protection from atherosclerosis (protected) have lower levels of the metabolites, suggesting an important effect of the microbiome on atherosclerosis. [22] We have found that plasma levels of these metabolites are significantly higher with even modest renal impairment, such as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (unpublished data). Among elderly patients, the average eGFR is below 60 ml/min/1.73 m2.[23] This means that even patients with modest renal impairment, including the elderly, should avoid egg yolk and limit intake of animal flesh (particularly red meat), not only because of their very high cholesterol content[24] but also because of the production of intestinal metabolites.

Blood pressure control

High blood pressure causes strokes because of the damage to the small arterioles in the base of the brain, where short straight arteries with few branches transmit pressure straight through the large artery to small resistance vessels. [25] This causes true lacunar infarctions and hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhages, which are virtually eliminated by good blood pressure control.[26] In the North American Carotid Endarterectomy Trial,[27] intracranial hemorrhages were reduced to 0.5% of strokes, at a time when ~20% of strokes were due to hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. This was accomplished by overcoming “therapeutic inertia”; investigators were sent a stiff letter every time the antihypertensive medication was not intensified in a patient whose blood pressure exceeded the benchmark.

What has been more difficult to overcome is “diagnostic inertia,” the failure to investigate the cause of the hypertension when patients’ blood pressures are not controlled by usual medication. [28] Spence proposed[29] that therapy could be improved by measuring plasma renin and aldosterone to identify the physiologic cause of hypertension. Usual care, as outlined in usual antihypertensive guidelines, tends to assume that all patients are the same and ignores the importance of the underlying cause of the hypertension in determining the best therapy. Approximately 20% of patients with resistant hypertension have primary aldosteronism, with a low plasma renin and high aldosterone, best treated with aldosterone antagonists. Approximately 6% (or possibly more) have an abnormality of the renal tubular epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) or its function, with low renin/low aldosterone phenotype, best treated with amiloride. Thus, after excluding rare causes such as pheochromocytoma, aortic coarctation or licorice ingestion, the best therapy for most patients with resistant hypertension can be determined by phenotyping with plasma renin and aldosterone. That hypothesis has been borne out in a study in Africa.

Patients with uncontrolled hypertension at three hypertension clinics in Africa were allocated to usual care versus physiologically individualized therapy based on the algorithm described in Table 3. In Kenya, no effect of this approach was observed; patients attended clinic less frequently, compliance was less, and amiloride was not available. “When only the sites in Nigeria and South Africa were considered, systolic control was obtained in 15.0% of UC vs. 78.6% of PhysRx (P < 0.0001), diastolic control in 45.0% vs. 71.4% (P = 0.04), and control of both in 15.0% vs. 66.7% (P = 0.0001). If only the Nigerian site (where patients were randomized to the two treatment strategies) is considered, systolic control was obtained in 15% of UC vs. 85% of PhysRx (P = 0.0001), and diastolic control in 45% vs. 75% (P = 0.11).”[30] In that trial, the biggest difference in medication between the usual care arm and the PhysRx arm was in prescription of amiloride: 19% of patients allocated to PhysRx versus 2.8% on usual care; P = 0.02.

Table 3.

Physiologically individualized therapy* based on renin/aldosterone profile

| Primary hyperaldosteronism | Liddle’s syndrome and variants (renal Na+ channel mutations) | Renal/renovascular | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renin | Low** | Low | High |

| Aldosterone | High** | Low | High |

| Primary treatment | Aldosterone antagonist | Amiloride | Angiotensin receptor blocker *** |

| (spironolactone or eplerenone) | |||

| Amiloride for men where | (rarely revascularization) | ||

| eplerenone is not available | |||

| (rarely surgery) |

(Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press from: Akintunde A, Nondi J, Gogo K, Jones ESW, Rayner BL, Hackam DG, et al. Physiological Phenotyping for Personalized Therapy of Uncontrolled Hypertension in Africa. Am J Hypertens 2017; 30: 923-30.)

It should be stressed that this approach is suitable for tailoring medical therapy in patients with resistant hypertension; further investigation would be required to justify adrenalectomy or renal revascularization.

Levels of plasma renin and aldosterone must be interpreted in the light of the medication the patient is taking at the time of sampling. In a patient taking an angiotensin receptor blocker (which would elevate renin and lower aldosterone), a plasma renin that is in the low normal range for that laboratory, with a plasma aldosterone in the high normal range, probably represents primary hyperaldosteronism for the purposes of adjusting medical therapy.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are less effective because of aldosterone escape via non-ACE pathways such as chymase and cathepsin; renin inhibitors are seldom used.

Antiplatelet therapy

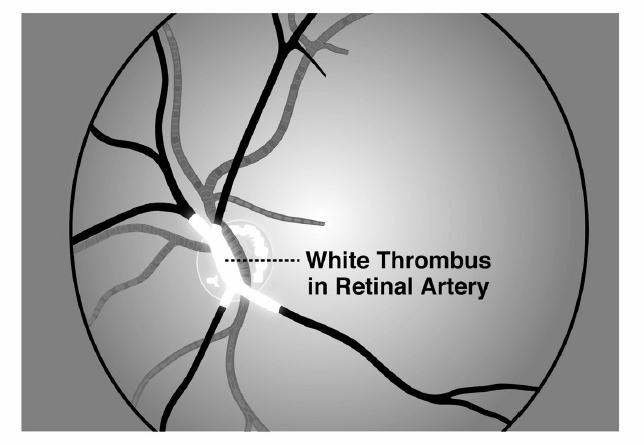

Antiplatelet agents prevent the formation of “white thrombus,” platelet aggregation in the setting of fast flow (Figure 1). They are indicated, therefore, for the prevention of stroke in large artery disease but are not effective for preventing cardioembolic stroke, which is due to “red thrombus” (a mesh of fibrin polymer with entrapped red blood cells).[31, 32]

Figure 1.

White thrombus in a retinal artery This phenomenon was perhaps first described by C Miller Fisher in a clinical case discussion in the New England Journal Of Medicine. I have seen it twice, when I happened to be present when patients with carotid stenosis had sudden loss of vision in one eye. Ophthalmoscopic examination revealed white thrombus, about the color of white bread, oozing gradually through the retinal artery; when the thrombus clears, vision returns; this often happens in quadrants or hemifields of the monocular vision as branches of the retinal artery clear sequentially. (Reproduced by permission of Vanderbilt University Press from: Spence J.D. How to Prevent Your Stroke. Vanderbilt University Press, 2006.)

A key issue that has surfaced in the recent years is the loss-of-function alleles of CYP2C19, the enzyme that activates the prodrug clopidogrel to its active form. This is present in ~30% of Europeans and more than 50% of Chinese people and results in loss of efficacy and higher risk of stroke among persons with those loss-of-function alleles. [33]

A combination of aspirin and clopidogrel improves outcomes,[34] but in some studies, the combination increased bleeding risk.[35] Most intracerebral hemorrhages could be prevented by controlling hypertension, and most major gastrointestinal bleeds could be prevented by detecting and treating Helicobacter pylori.

A solution to the pharmacokinetic issue with clopidogrel would be to use ticagrelor, an active drug that does not require CYP2C19 for activation. [36] Although the major trial with ticagrelor versus aspirin did not show significant benefit of ticagrelor, there was a trend to reduced stroke risk in Asian patients [37] and a significant reduction of stroke with ticagrelor in patients with large artery disease.[38] As large artery disease is the indication for antiplatelet therapy, we should probably be using ticagrelor, but for the high cost.

Anticoagulation

With the availability of the direct-acting anticoagulants, the paradigm for anticoagulation has changed. While in the past, the risk of bleeding with warfarin was so high, and the difficulty of controlling anticoagulation by measurement of the international normalized ratio (INR) was so great, that physicians were very reluctant to prescribe warfarin and patients were very reluctant to take it. This resulted in severe under-anticoagulation of patients who clearly should have been taking warfarin. Gladstone et al.[39] reported that among patients admitted to hospital with stroke and atrial fibrillation (AF) with an indication for warfarin and no contraindication, only 40% were taking warfarin, 30% were taking antiplatelet agents, and 29% were taking no antithrombotic medications. Among those taking warfarin, only 10% of patients were adequately anticoagulated.

The availability of new direct-acting oral anticoagulants that are much safer than warfarin changes the paradigm (Table 4). Two studies reported that apixaban[40] and rivaroxaban[41] were not significantly more likely than aspirin to cause severe bleeding. This means that because the risk of recurrent stroke is highest soon after an initial event,[42] it is prudent to anticoagulate a patient with suspected cardioembolic stroke while awaiting the results of diagnostic tests such as echocardiography and Holter recording. In some patients in whom the suspicion of cardioembolic stroke is very strong (e.g., patients with normal arteries, normal blood pressure, no other evident cause of stroke after a comprehensive investigation, and strokes in multiple vascular territories), it may be more prudent to continue anticoagulation even if initial cardiac investigations are negative.

Table 4.

Properties of Direct-acting Oral Anticoagulants*

| Characteristic | Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | Apixaban | Edoxaban |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Factor IIa | Factor Xa | Factor Xa | Factor Xa |

| Prodrug | Yes | No | No | No |

| Dosing | BID | OD | BID | OD |

| Bioavailability | 6.5% | 80–100%* | 50% | 62% |

| Half-life | 12–14 h | 5–13 h | 8–15 h | 10–14 h |

| Renal clearance | 85% | ~33% | ~27% | ~50% |

| Cmax | 1–2 h | 2–4 h | 3–4 h | 1–2 h |

| Interactions | P-gp inhibitors | Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 and P-gp | Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 and P-gp | P-gp inhibitors |

OD: once daily; BID: twice daily; CYP3A4: intestinal cytochrome P450 3A4; Cmax: time to maximal blood concentration; P-gp: P-glycoprotein

In order of appearance on the market.

The EMBRACE trial reported that among patients with cryptogenic stroke and a negative Holter recording, a repeat Holter recording detected AF in only 3% of patients; in contrast, a 1-month recording detected AF in 16% of patients. In that study, patients with frequent atrial extrasystoles had a 40% chance of having AF detected within a month. The CRYSTAL study reported that among patients with implanted devices, 30% had AF detected within a year. Thus AF is often missed when only a Holter recording is performed. An issue that has not yet been resolved is how frequent and how prolonged AF needs to be to warrant anticoagulation.

Patent foramen ovale

Early clinical trials of percutaneous closure did not show significant benefit, but a pooled analysis of early trials[43] did reveal a slight reduction of stroke with closure. Then in 2018, three studies were published, showing benefit of percutaneous closure, and an editorial summarized the results.[44] There are reasons for concern that these recent results may result in inappropriate procedures in patients who may not benefit. One issue that has not received sufficient attention is that percutaneous closure was significantly better than antiplatelet therapy but was not significantly better than anticoagulants.

As ~25% of the population has a PFO, and only ~5.5% of strokes are due to paradoxical embolism, the PFO will be incidental in ~80% of all stroke patients and ~50% of those with ESUS. [45] The ROPE score [46] mentioned in the Editorial assesses the likelihood that a stroke is an embolic stroke of unknown source (ESUS).

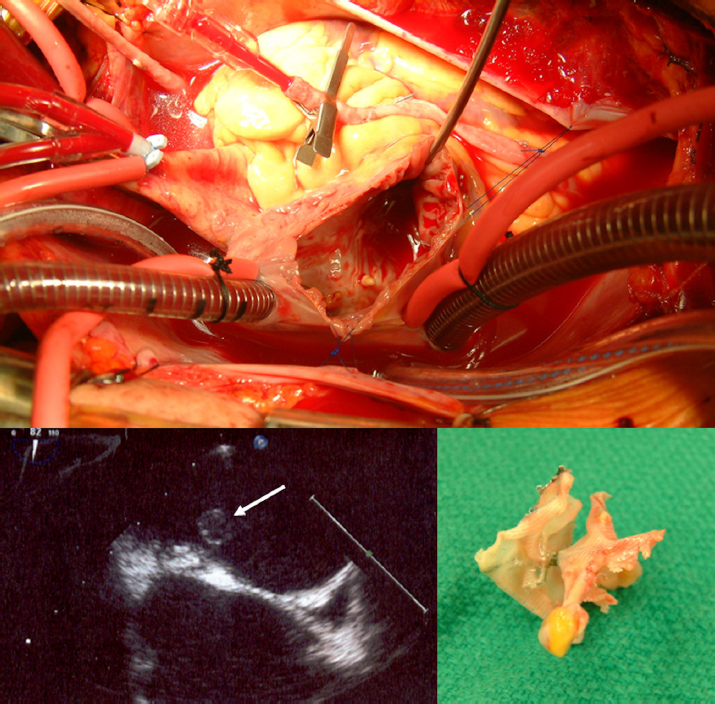

There can be serious complications of percutaneous closure. These include embolization of the device, with fatal obstruction of the aortic valve, or embolization to distal arteries requiring emergency surgery. There is an increase in AF after percutaneous closure, and thrombus may form on the left atrial side of the device, as shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, because a paradoxical embolus is by definition the same as a pulmonary embolus, some patients with paradoxical embolism may require long-term or life-long anticoagulation. Placement of a closure device requires antiplatelet therapy, so some patients who should be anticoagulated may be inappropriately switched to antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous closure.

Figure 2.

Thrombus on the left atrial side of a percutaneous PFO closure device The patient had a Stroke in 2000 at the age of 54 years; PFO closure was performed using a CardioSEAL device in 2003. In 2008, he had a transient ischemic attack; echocardiography showed thrombus on the device. The thrombus failed to dissolve in 6 months of intensive anticoagulation, so open heart surgery was performed in 2009 to remove the thrombus and the device, with surgical closure of the PFO. The upper panel shows the open left atrium; lower left image is the echocardiographic image of the thrombus (white arrow). Lower right image is the surgically removed device. (Courtesy of Dr. Bob Kiaii and Dr. Bryan Dias, University Hospital, London, Canada.)

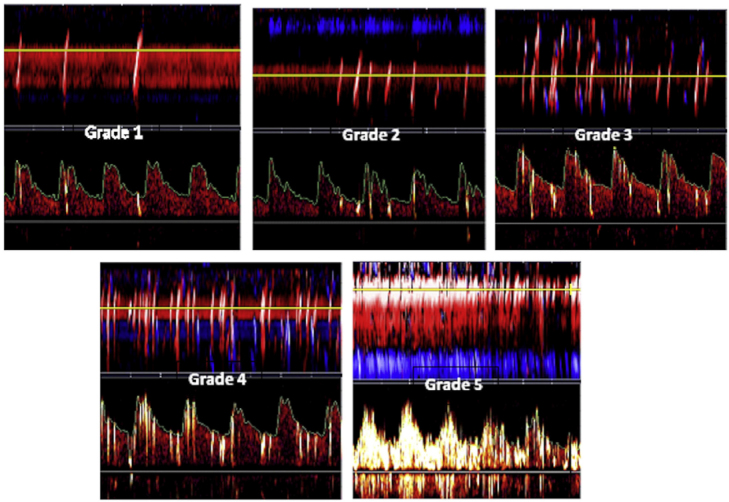

In deciding which patients would benefit from closure, it is, therefore, important to assess the likelihood that a patient had a paradoxical embolus. One can and should go beyond the ROPE score in two additional ways: first, it is important to take a careful history for clinical clues to paradoxical embolism,[47] shown in Table 5. Second, it is useful to assess the size of the right-left shunt with transcranial Doppler (TCD), which is more sensitive than echocardiography. Recurrent stroke is significantly more likely with a Grade III or higher shunt.[48] Figure 3 shows the Spencer grading system for shunt size.

Table 5.

Clinical clues to paradoxical embolism

| Cryptogenic stroke, plus any of |

| Dyspnea*, tachycardia at onset |

| ↓ pO2, ↓ pCO2 |

| Loud P2, Pulmonic regurge |

| Loss of consciousness at onset of carotid stroke |

| Long ride in a car, airplane; prolonged sitting* |

| Swollen leg, previous DVT, varicose veins * |

| Pulmonary emboli in past* |

| Valsalva maneuver* |

| Waking up with stroke* |

| Sleep apnea* |

(Based on data from: Ozdemir AO, Tamayo A, Munoz C, Dias B, Spence JD. Cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale: clinical clues to paradoxical embolism. J Neurol Sci 2008; 275: 121-7.)

P<0.05.

Figure 3.

Grading of right-left shunt in PFO by transcranial Doppler (TCD) Transcranial Doppler screen shots of Spencer shunt grades are shown for example of cases missed by trans-esophageal echocardiography with sedation. It can be seen that the presence of bubbles in the cerebral arteries is obvious; besides the visual output on the screen, a loud signal is heard from the audio output with each bubble crossing the patent foramen ovale. Grade 0, no microemboli detected; grade 1, 1–10 microemboli; grade 2, 11–30 microemboli; grade 3, 31–100 microemboli; grade 4, 101–300 microemboli; and grade 5, >300 microemboli. (Reproduced by permission of Elsevier from: Tobe J, Bogiatzi C, Munoz C, Tamayo A, Spence JD. Transcranial Doppler is Complementary to Echocardiography for Detection and Risk Stratification of Patent Foramen Ovale. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32: 986 e9-e16.)

Percutaneous closure of PFO should be performed only in patients who are likely to benefit.

Identifying high-risk asymptomatic carotid stenosis

Most patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis (~90%) have such a low risk of stroke that they will be better treated with intensive medical therapy (as described below) than with either stenting or endarterectomy. Methods for identifying high-risk patients who could benefit from intervention have recently been reviewed. [49,50] Available methods include ultrasound features of plaque such as echolucency, juxtaluminal black plaque and plaque texture, plaque inflammation on PET/CT, ulceration, reduced cerebral blood flow reserve, intraplaque hemorrhage on MRI, and TCD detection of microemboli. The best validated is TCD embolus detection. Among patients with asymptomatic stenosis, the 10% with two or more microemboli during 1 h of monitoring had a 1-year risk of stroke of 15.6%, compared with a 1% risk among the 90% of patients with no microemboli. The risk with one or more emboli during an hour of monitoring, with repeated monitoring, is ~7%, still higher than the risk of surgery or stenting. Patients with asymptomatic stenosis should not be subjected to the risk of endarterectomy or stenting unless they have been identified by such methods as having a higher risk of stroke or death than the risk with intervention.

Treating arteries instead of treating risk factors

In 2002, Spence et al.[51] reported that a high carotid plaque burden was a strong predictor of cardiovascular risk. Patients in the top quartile of total plaque area (>119 mm2) had a 19.5% 5-year risk of stroke, cardiovascular death, or myocardial infarction, after adjustment for a broad panel of coronary risk factors. During the first year of follow-up, half the patients had plaque progression despite usual treatment, and those with progression had twice the risk of those events compared to patients with stable plaque or regression. [51] Fuster and colleagues reported that carotid plaque burden was highly correlated with coronary calcium scores[52] and as predictive of cardiovascular risk.[53]

The recognition that usual care was failing half our patients led to a new approach to vascular prevention: “treating arteries instead of treating risk factors.”[54] This approach was implemented in the vascular prevention clinics at our hospital in 2003; by 2010, we had evidence that in high-risk patients with asymptomatic stenosis, it was highly effective. The percentage of patients with TCD microemboli declined from 12.6% to 3.7%, carotid plaque progression slowed significantly, and both the 2-year risk of stroke and myocardial infarction declined by more than 80%. [55]

During 15 years of using this approach in thousands of patients, it has become apparent that some patients have “resistant atherosclerosis.” They continue to have plaque progression despite very low levels of serum LDL-C. Both age and renal impairment increase resistance to therapy. Such patients will require new approaches to treat atherosclerosis; one that is contemplated based on our findings regarding the intestinal microbiome is repopulation of the intestinal microbiome.

Conclusion

In recent years, there have been many advances in stroke prevention. Implementing them successfully requires dedication, perseverance, and intelligent interpretation of the evidence. It was estimated in 2007 that recurrent strokes could be reduced by 80% with a combination of lifestyle modification and medical therapy.[56] It seems likely that with recent advances, we could achieve even more. We owe our patients every effort; with the aging of the population, strokes can be expected to increase in frequency, and preventable strokes are disastrous for the patient, the family, and the economy of every country.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Spence JD. Diet for stroke prevention. Stroke Vascular Neurol. 2018;0:e000130. doi: 10.1136/svn-2017-000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Rebuild the food pyramid. Sci Am. 2003;288:64. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0103-64. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keys A.. Mediterranean diet and public health: personal reflections. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:1321S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1321S. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708681. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renaud S, de Lorgeril M, Delaye J, Guidollet J, Jacquard F, Mamelle N. Cretan Mediterranean diet for prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:1360S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1360S. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383. –. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, Covas MI, Corella D, Aros F. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:e34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800389. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spence JD. Homocysteine Lowering with B Vitamins for Stroke Prevention—A History. US Neurol. 2018;14:35. –. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spence JD, Yi Q, Hankey GJ. B vitamins in stroke prevention: time to reconsider. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:750. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30180-1. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, Spence JD, Pettigrew LC, Howard VJ. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:565. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.565. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.B vitamins in patients with recent transient ischaemic attack or stroke in the VITAmins TO Prevent Stroke (VITATOPS) trial: a randomised, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:855. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70187-3. VITATOPS Trial Study Group. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spence JD. Effects of the intestinal microbiome on constituents of red meat and egg yolks: a new window opens on nutrition and cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:150. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.11.019. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang WH, Wang Z, Kennedy DJ, Wu Y, Buffa JA, Agatisa-Boyle B. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305360. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang WHW, Wang Z, Levinson BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X. Intestinal Microbiota Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine and Cardiovascular Risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Liabeuf S, Meert N, Glorieux G, Temmar M. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1551. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03980609. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liabeuf S, Barreto DV, Barreto FC, Meert N, Glorieux G, Schepers E. Free p-cresylsulphate is a predictor of mortality in patients at different stages of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1183. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp592. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meijers BK, Bammens B, De Moor B, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y, Evenepoel P. Free p-cresol is associated with cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1174. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.31. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poesen R, Claes K, Evenepoel P, de Loor H, Augustijns P, Kuypers D. Microbiota-Derived Phenylacetylglutamine Associates with Overall Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3479. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015121302. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neirynck N, Glorieux G, Schepers E, Pletinck A, Dhondt A, Vanholder R. Review of protein-bound toxins, possibility for blood purification therapy. Blood Purif. 2013;35:45. doi: 10.1159/000346223. Suppl 1. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dou L, Jourde-Chiche N, Faure V, Cerini C, Berland Y, Dignat-George F. The uremic solute indoxyl sulfate induces oxidative stress in endothelial cells. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02540.x. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dou L, Sallee M, Cerini C, Poitevin S, Gondouin B, Jourde-Chiche N. The cardiovascular effect of the uremic solute indole-3 acetic Acid. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:876. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121283. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogiatzi C, Gloor G, Allen-Vercoe E, Reid G, Wong RG, Urquhart BL. Metabolic products of the intestinal microbiome and extremes of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2018;273:91. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.04.015. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spence JD, Urquhart BL, Bang H. Effect of renal impairment on atherosclerosis: only partially mediated by homocysteine. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:937. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv380. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spence JD. Dietary cholesterol and egg yolk: not recommended for patients at risk of vascular disease. J Transl Int Med. 2016;4:20. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0005. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spence JD. B.M.Brenner JHL, editor. Hypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. 2nd edition. New York: Raven Press; 1995. Cerebral consequences of hypertension; pp. 745–53. –. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spence JD. Antihypertensive drugs and prevention of atherosclerotic stroke. Stroke. 1986;17:808. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.5.808. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators [see comments]. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1415. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spence JD, Rayner BL. J Curve and Cuff Artefact, and Diagnostic Inertia in Resistant Hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;67:32. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06562. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spence JD. Lessons from Africa: the importance of measuring plasma renin and aldosterone in resistant hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:254. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.11.010. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akintunde A, Nondi J, Gogo K, Jones ESW, Rayner BL, Hackam DG. Physiological Phenotyping for Personalized Therapy of Uncontrolled Hypertension in Africa. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:923. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx066. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deykin D.. Thrombogenesis. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:622. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196703162761107. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caplan LR, Fisher M. The endothelium, platelets, and brain ischemia. Rev Neurol Dis. 2007;4:113. –. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, Li H, Johnston SC, Lin Y. Association Between CYP2C19 Loss-of-Function Allele Status and Efficacy of Clopidogrel for Risk Reduction Among Patients With Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. JAMA. 2016;316:70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8662. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schomig A.. Ticagrelor--is there need for a new player in the antiplatelet-therapy field? N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0906549. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Minematsu K, Wong KS, Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H. Ticagrelor in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack in Asian Patients: From the SOCRATES Trial (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated With Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes) Stroke. 2017;48:167. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014891. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, Easton JD, Evans SR, Held P. Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischaemic attack of atherosclerotic origin: a subgroup analysis of SOCRATES, a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:301. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30038-8. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gladstone DJ, Bui E, Fang J, Laupacis A, Lindsay MP, Tu JV. Potentially preventable strokes in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation who are not adequately anticoagulated. Stroke. 2009;40:235. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.516344. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, Diener HC, Hart R, Golitsyn S. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:806. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007432. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weitz JI, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, Bauersachs R, Beyer-Westendorf J, Bounameaux H. Rivaroxaban or Aspirin for Extended Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700518. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amarenco P. Steering Committee Investigators of the TIAregistry.org.Risk of Stroke after Transient Ischemic Attack or Minor Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:387. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1606657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kent DM, Dahabreh IJ, Ruthazer R, Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Carroll JD. Device Closure of Patent Foramen Ovale After Stroke: Pooled Analysis of Completed Randomized Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:907. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.023. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ropper AH. Tipping Point for Patent Foramen Ovale Closure. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1093. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1709637. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kent DM, Thaler DE. Is patent foramen ovale a modifiable risk factor for stroke recurrence? Stroke. 2010;41:S26. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595140. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kent DM, Ruthazer R, Weimar C, Mas JL, Serena J, Homma S. An index to identify stroke-related vs incidental patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic stroke. Neurology. 2013;81:619. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a08d59. et al. –. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozdemir AO, Tamayo A, Munoz C, Dias B, Spence JD. Cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale: clinical clues to paradoxical embolism. J Neurol Sci. 2008;275:121. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.08.018. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tobe J, Bogiatzi C, Munoz C, Tamayo A, Spence JD. Transcranial Doppler is Complementary to Echocardiography for Detection and Risk Stratification of Patent Foramen Ovale. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:986 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.12.009. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paraskevas KI, Spence JD, Veith FJ, Nicolaides AN. Identifying which patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis could benefit from intervention. Stroke. 2014;45:3720. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006912. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paraskevas KI, Veith FJ, Spence JD. How to identify which patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis could benefit from endarterectomy or stenting. Stroke Vascular Neurol. 2018;0:e000129. doi: 10.1136/svn-2017-000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spence JD, Eliasziw M, DiCicco M, Hackam DG, Galil R, Lohmann T. Carotid plaque area: a tool for targeting and evaluating vascular preven-tivetherapy. Stroke. 2002;33:2916. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000042207.16156.b9. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sillesen H, Muntendam P, Adourian A, Entrekin R, Garcia M, Falk E. Carotid plaque area: a tool for targeting and evaluating vascular preventivetherapy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:681. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.03.013. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baber U, Mehran R, Sartori S, Schoos MM, Sillesen H, Muntendam P. Prevalence, impact, and predictive value of detecting subclinical coronary and carotid atherosclerosis in asymptomatic adults: the BioImage study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.017. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spence JD, Hackam DG. Treating arteries instead of risk factors: a paradigm change in management of atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2010;41:1193. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.577973. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spence JD, Coates V, Li H, Tamayo A, Munoz C, Hackam DG. Effects of Intensive medical therapy on microemboli and cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:180. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.289. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hackam DG, Spence JD. Combining multiple approaches for the secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke: a quantitative modeling study. Stroke. 2007;38:1881. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475525. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spence JD. How to prevent your stroke. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2006. pp. 163–204. –. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bonäa KH, Njolstad I, Ueland PM, Schirmer H, Tverdal A, Steigen T. Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055227. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lonn E, Yusuf S, Arnold MJ, Sheridan P, Pogue J, Micks M. Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060900. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galan P, Kesse-Guyot E, Czernichow S, Briancon S, Blacher J, Hercberg S. Effects of B vitamins and omega 3 fatty acids on cardiovascular diseases: a randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c6273. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spence JD, Bang H, Chambless LE, Stampfer MJ. Vitamin Intervention For Stroke Prevention trial: an efficacy analysis. Stroke. 2005;36:2404. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185929.38534.f3. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.House AA, Eliasziw M, Cattran DC, Churchill DN, Oliver MJ, Fine A. Effect of B-vitamin therapy on progression of diabetic nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1603. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.490. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huo Y, Li J, Qin X, Huang Y, Wang X, Gottesman RF. Efficacy of folic acid therapy in primary prevention of stroke among adults with hypertension in China: the CSPPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1325. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2274. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu X, Qin X, Li Y, Sun D, Wang J, Liang M. Efficacy of Folic Acid Therapy on the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease: The Renal Substudy of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1443. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4687. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koyama K, Yoshida A, Takeda A, Morozumi K, Fujinami T, Tanaka N. Abnormal cyanide metabolism in uraemic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1622. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.8.1622. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loland KH, Bleie O, Borgeraas H, Strand E, Ueland PM, Svardal A. The association between progression of atherosclerosis and the methylated amino acids asymmetric dimethylarginine and trimethyllysine. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064774. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koyama K, Ito A, Yamamoto J, Nishio T, Kajikuri J, Dohi Y. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of short-term coadministration of methylcobalamin and folate on serum ADMA concentration in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:1069. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.035. et al. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rader DJ, Ischiropoulos H. ‘Multipurpose oxidase’ in atherogenesis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1146. doi: 10.1038/nm1007-1146b. –. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]