Abstract

Objective

Pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) is not a diagnosis but a transient state used to classify a woman when she has a positive pregnancy test without definitive evidence of an intra-uterine or extra-uterine pregnancy on transvaginal ultrasonography. Management of a persisting PUL varies substantially, including expectant or active management. Active management can include uterine cavity evacuation or systemic administration of methotrexate. To date, no consensus has been reached on whether either management strategy is superior or non-inferior to the other.

Design

Randomized controlled trial

Setting

Academic medical centers

Patients

We plan to randomize 276 persisting PUL-diagnosed women who are 18 years or older from Reproductive Medicine Network clinics and additional interested sites, all patients will be followed for 2 years for fertility and patient satisfaction outcomes.

Interventions

Randomization will be 1:1:1 ratio between expectant management, uterine evacuation and empiric use of methotrexate. After randomization to initial management plan, all patients will be followed by their clinicians until resolution of the PUL. The clinician will determine whether there is a change in management, based on clinical symptoms, and/or serial human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations and/or additional ultrasonography.

Main outcome

The primary outcome measure in each of the 3 treatment arms is the uneventful clinical resolution of a persistent PUL without change from the initial management strategy. Secondary outcome measures include: number of ruptured ectopic pregnancies, number and type of reinterventions (additional methotrexate injections or surgical procedures), treatment complications, adverse events, number of visits, time to resolution, patient satisfaction, and future fertility.

Conclusion

This multicenter randomized controlled trial will provide guidance for evidence-based management for women who have persisting pregnancy of unknown location.

Keywords: PUL, Methotrexate, Uterine Evacuation, Ectopic Pregnancy, Biomarkers

Background

A woman with pain and bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy is at risk for ectopic pregnancy (EP) and should be distinguished from a woman with an ongoing potentially viable intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) and from a woman with a miscarriage. EP is defined as the implantation of an embryo outside the uterus. EP is a major cause of maternal morbidity and is responsible for 6% of pregnancy-related deaths [1, 2]. However, if diagnosed and treated early and before rupture, morbidity is limited and conservative management is preferred [3]. Early diagnosis allows for procedures that preserve fallopian tube function and fertility [4].

Diagnosis is straightforward if ultrasound evaluation definitively identifies a definitive IUP or EP [5]. However, ultrasound can be inconclusive in early pregnancy (no evidence of a gestation in the uterus or the adnexa) in up to 40% of women with a symptomatic first trimester pregnancy [6]. This clinical quandary is termed a ‘pregnancy of unknown location’ (PUL). A PUL is not a diagnosis but a transient state in the diagnostic process of a woman at risk for EP [7]. The management of a woman with a PUL necessitates close follow up and repeated diagnostic testing until a definitive diagnosis is reached. This can include serial serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations, repeat ultrasound, or uterine evacuation. While the final diagnosis is either an early viable intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), miscarriage, or a visualized ectopic pregnancy, there is a clinical dilemma regarding when or if intervention is needed to make a definitive diagnosis. [8, 9, 10]. In addition, when (hCG) values are not declining spontaneously, there is no consensus regarding when or if intervention is necessary [8, 9, 10].

During the course of evaluation of a woman with a PUL, up to one third of women will be found to have serial (hCG) values that neither rise nor decline in a pattern suggesting an ongoing viable gestation or a spontaneously resolving pregnancy loss; termed a persisting pregnancy of unknown location (PPUL). These women are at high risk for ectopic pregnancy. While it is important to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy early, the desired goals for a woman with a PPUL may vary, but usually include wishing to minimize intervention, time lost from work, inconvenience, and psychological trauma as she undergoes further evaluation and possible pregnancy loss. These competing priorities have resulted in controversies regarding the utility and role of uterine evacuation, when (or if) presumptive treatment with methotrexate is warranted, and the role of expectant management.

Surgical exploration in the form of uterine evacuation (dilation and curettage) is often performed to confirm the location of the persistent trophoblastic tissue. If trophoblastic tissue is found at the time of uterine evacuation, then a miscarriage has been diagnosed and treated. If the (hCG) concentration does not decline after uterine evacuation, trophoblastic tissue is presumed to be outside of the uterine cavity and an ectopic gestation is indirectly confirmed [7]. This “nonvisualized’ ectopic pregnancy can then be treated medically with methotrexate (MTX), [8, 9, 11], if appropriate criteria are met.

Some though have advocated that it is not necessary to perform a uterine evacuation to determine the location of the gestation; the PPUL can simply be treated with methotrexate [12]. Alternatively, both early miscarriage and early ectopic pregnancy can be managed expectantly, [13–17] and one multicenter randomized controlled trial demonstrated no difference in the primary treatment success of either single-dose methotrexate versus expectant management [18]. Often the strategy of choice for the management of a PPUL is based on geographic location and training [19].

The goal of this pragmatic randomized controlled trial is to determine if active management (uterine evacuation or MTX) of women with a PPUL is superior to expectant management, if two common active management strategies of a women are non-inferior to each other, and to determine which management strategies are optimal based on cost, number of procedures, side effects, patient preference, and time to resolution.

Materials and Methods

The ACT or NOT trial is a multi-center randomized clinical trial designed to identify the optimal management for a woman with a PPUL. Study participants will be recruited from the clinics of the Reproductive Medicine Network and affiliated entities after obtaining written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania IRB which served as a central IRB (IRB # 815013), performed under IND # 65407 and clinical trials registration number NCT02152696.

Population

For inclusion, participants must be >18 years old, hemodynamically stable, and identified to have a PPUL. A PPUL is defined as no definitive ultrasound evidence of an intra-uterine or extra-uterine gestation and serial (hCG) confirming non-viability. Ultrasound findings may include a normal uterus and adnexa or nonspecific hypoecchoic area in the uterus (without a yoke sac) or a nonspecific adnexal mass [7]. Prior to enrolment, a second opinion confirming that the pregnancy is non-viable is required. Ultrasound must be performed within 7 days prior to randomization.

Persistence of (hCG) consistent with a nonviable gestation is defined as at least 2 consecutive hCG values (over 2–14 days), showing <15% rise/day, or <50% fall between the first and last value. This abnormal pattern of serial (hCG) confirms that the gestation is nonviable. A minimal rise for a viable intrauterine pregnancy is 23% per day or 53% for two days [4]. A maximum rise per day (15%) was calculated and conservatively rounded to accommodate ease of determination of hCG value over a 7-day period: i.e. criteria are 30% or less for hCG values 2 days apart, 50% or less for values 3 days apart, 75% or less for 4 days, 100% or less for 5 days, 130% or less for 6 days, and 166% or less for values 7 days apart.

Exclusion criteria include the following: A definitive sign of gestation including ultrasound visualization of a gestational sac with a yolk sac, with or without an embryo, in the uterus or adnexa [7], the most recent hCG >5,000 mIU/mL, patient obtaining care in relation to a recently completed pregnancy (delivery, spontaneous or elective abortion), diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, participant unwilling or unable to comply with study procedures, known hypersensitivity to MTX, presence of clinical contraindications for treatment with MTX, prior medical or surgical management of this gestation and participant unwilling to accept a blood transfusion. The presence of free fluid visualized by pelvic ultrasound was not an exclusion criterion.

Randomization

After confirming eligibility and informed consent, participants will be randomized by a central randomization office utilizing an internet-based program at the data coordinating center. Block randomization of 3 and 6 were used with the chances being 2:1 between the two choices. Randomization will be 1:2 between expectant management and active management, and 1:1 between active management A and active management B (thus randomization will be 1:1:1 into the three management arms). (See below and Figure 1)

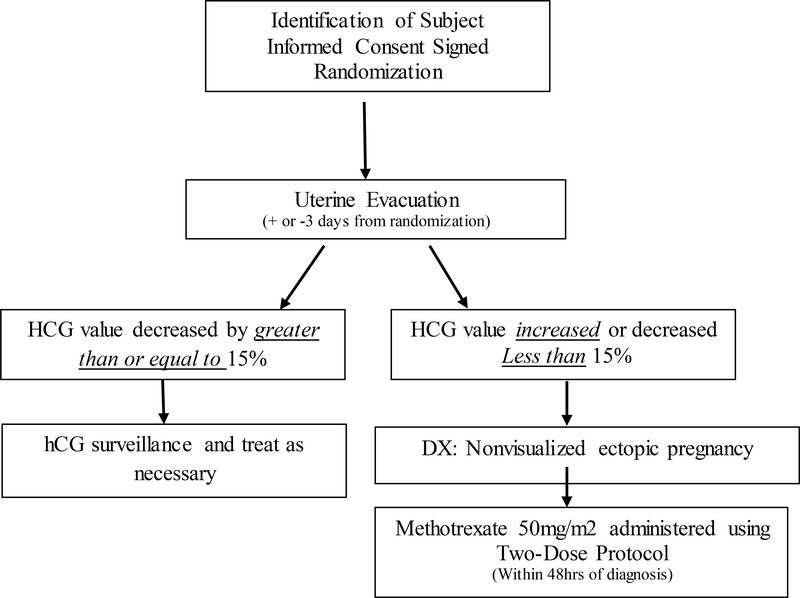

Figure 1:

ACT or NOT study flowchart, the flowchart below summarizes study methods

The arms will be: 1) Expectant management which consists of close monitoring of the PPUL without any intervention. 2) Active management A: consists of a uterine evacuation (or D&C) followed by MTX (50 mg/m2) for those who do not have a drop in hCG suggesting trophoblastic tissue was removed from the uterus. (Figure 2). 3) Active management B: consists of empiric treatment with MTX.

Figure 2:

Active Management A Flowchart

Expectant management:

In this arm the plan is to expectantly manage the PPUL with close clinical surveillance of signs and symptoms, and serial serum (hCG) concentrations. The frequency of follow up was at least every 4–7 days from randomization, and more often if clinically indicated. Success is defined as complete elimination of (hCG) from the serum, without medical or surgical intervention. Failure is defined as the need for surgical or medical intervention to treat a persistent or ruptured ectopic pregnancy, to complete a miscarriage, or to treat heavy bleeding.

Active management A: Uterine evacuation followed by MTX for those that have evidence of a non-visualized EP:

In this management arm, a uterine evacuation will be scheduled within three days of randomization. A repeat serum (hCG) value will be obtained within 12–36 hours of completion of the procedure. Based on this value one of two courses will be followed: a) If the value has decreased by ≥15% the uterine evacuation is considered to likely have removed trophoblastic tissue from the uterus. The subject is followed as an outpatient until complete resolution of (hCG) from the serum. Further treatment is based on results of serial (hCG) values or symptoms. b) If the value has decreased ≤ 15% (or increased) the uterine evacuation is considered not to have removed the products of conception and the trophoblastic tissue is presumed to be ectopically located. In this case, the diagnosis of a non-visualized ectopic pregnancy has been confirmed [5, 8]. Treatment of the non-visualized ectopic pregnancy will be with intramuscular MTX using the 2-dose protocol [8, 9, 20]. The administration of the first MTX injection should be within 48 hours of making the diagnosis of a non-visualized EP. After administration of MTX per protocol, the subject is followed as an outpatient until complete resolution of (hCG) from the serum. Further treatment is based on results of serial (hCG) values or symptoms.

Success of this management arm will be complete elimination of (hCG) from the serum after either uterine evacuation only (situation “a”) or after uterine evacuation and MTX administration (situation “b”), without further surgical intervention. Failure is defined as the need for surgical or additional medical intervention to treat a persistent or ruptured ectopic pregnancy, to complete a miscarriage or treat heavy bleeding. The use of MTX to treat a persistent ectopic pregnancy will be collected as a secondary outcome, but will not be defined as failure [8, 9, 20].

Active management B: Empiric treatment with MTX:

In this management arm, treatment will proceed directly to intramuscular MTX. Treatment will be with intramuscular MTX using the 2-dose protocol [8, 9, 20], administered within two days of randomization.

Success of this management arm will be complete elimination of (hCG) from the serum after MTX administration, without surgical intervention. Failure is defined as the need for surgical or additional medical intervention to treat a persistent or ruptured ectopic pregnancy, to complete a miscarriage or treat heavy bleeding. The need for MTX to treat a persistent ectopic pregnancy will be collected as a secondary outcome, but will not be defined as failure [8, 9, 20].

Follow up

Once the subject is randomized to initial management strategy, her clinical care will be continued with her treating physician. Standard of care is to follow the subject until complete resolution of the PPUL, defined by undetectable serum (hCG), or treatment of an ectopic pregnancy. Follow up will include serial outpatient monitoring of (hCG) values, monitoring patient signs and symptoms, and ultrasound as needed. Based on these findings, the treating physician may judge that surgical or medical intervention is required to diagnose or treat an ectopic pregnancy or miscarriage. The subject may also elect to change treatment strategies after randomization.

Participants will be screened for eligibility for MTX only after it is determined that they will receive it (i.e. via randomization or clinical discretion). Those who are randomized to receive MTX, but then are not able to receive it due to safety laboratory values, will be managed per the judgment of her treating physician.

Information collected at baseline will include age, race, ethnicity, site of treatment, past gynecologic, obstetric and medical history, characterization of the presenting signs and symptoms, chief complaint, amount of pain (scale of 1–10) and bleeding (none, scant, light, heavy). Results of laboratory tests will include (hCG) and relevant chemistry, hematology, blood type, and transvaginal pelvic ultrasound results.

Information collected at subsequent encounters will include: date, location (outpatient, emergency room, inpatient), change in symptoms (increase or decrease in pain and or bleeding), serum hCG value and other relevant laboratory values, results of subsequent ultrasound, adverse events and procedures performed (i.e. dilation and evacuation, injection with MTX, laparoscopy). Serum and plasma samples will be obtained to assess for potential molecular markers of success at randomization (before treatment) and at approximately weekly intervals until resolution, as available.

Quality of life, acceptability, and cost will be assessed with a questionnaire administered 3 weeks after resolution assessing side effects, satisfaction and time away from work. Long term follow up will be assessed with a questionnaire, every six months for a period of 24 months. Questions will focus on the desire for pregnancy, contraceptive use, infertility treatment, and the occurrence of any pregnancies and their outcome (including live birth, miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy). We will collect data regarding whether a hysterosalpingogram or a diagnostic laparoscopy with Chromopertubation is performed to assess the status of the tubes. However, assessment of tubal patency by means of a hysterosalpingogram or a diagnostic laparoscopy is not part of the protocol.

The primary outcome measure is the frequency of clinical resolution for each of the management strategies. Clinical resolution is defined as an uneventful decline of serum (hCG) to an undetectable level (less than 5 mIU/mL) without deviation from the initial intervention strategy. Secondary outcome measures are: number of ruptured ectopic pregnancies, number and type of re-interventions (additional methotrexate injections or surgical procedures), number of procedure (labs tests, ultrasounds), treatment complications, adverse events, number of visits, time to resolution, patient satisfaction, and future fertility.

Statistical Plan

Sample Size Determination

The assumptions for sample size for the trial are designed to test two hypotheses. The primary hypothesis will test the superiority of active management (both active management arms combined) to expectant management with 90% power. The sample size requirement for the comparison of 7% failure (active treatments combined) vs. 25% failure (expectant) requires 160 women allocated to active and 80 to expectant management (Table 1). With this sample size we will conclude that if the difference between active and expectant management is greater than 18%, active treatment is superior. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Table 1:

The sample size requirement comparisons of active expectant management

| Sample Size Comparisons | Expectant Management | Active Management |

|---|---|---|

| Expected success rate | 75% | 93% |

| Expected failure rate | 25% | 7% |

| Number of subjects | 80 | 160 |

| Number of subjects with 15% inflation | 92 | 184 |

Our secondary hypothesis is to determine which active management strategy is optimal. To address this question we proposed using a non-inferiority approach to the two active management arms (Table 2). With 1:1 randomization within the active treatment arm (80 in each active management strategy), assuming failure rates of 6% vs. 8%, with 80% power, we can test a non-inferior margin of 12%. Under the assumption that the true difference between the two treatments is 1% any observed difference in the failure rate of less than 13% will be considered non-inferior. If the two failure rates are similar, and within the bounds of the CI, secondary outcomes will be considered to assess which is optimal. We have inflated the sample size by 15% to 276 women [92, 92, 92] to account for loss to follow-up.

Table 2:

Non-inferiority approach to the two active management arms

| Non-inferiority approach to the two active management arms | Active management strategy A ‘Uterine evacuation followed by MTX for some’ | Active management B ‘Empiric treatment with MTX for all” |

|---|---|---|

| Expected success rate | 94% | 92% |

| Expected failure rate | 6% | 8% |

| Number of subjects | 80 | 80 |

| Number of subjects with 15% inflation | 92 | 92 |

Statistical Methods

The percent failed of initial treatment course will be compared for each study arm, using logistic regression models which will include adjustment for any covariates determined to be imbalanced among the treatment arms. The primary analysis will assume ‘Intent to Treat’ (ITT) principles, whereby every participant randomized will be included for analysis. An “as treated” participant analysis will also be conducted but considered secondary. We also plan to explore an adjusted model to account for the participant’s or clinician’s reasons for change in allocated treatment post randomization [21]

For our primary hypothesis, we theorize that there will be a lower clinical resolution rate for expectant management compared to active management (both active management arms combined). For our secondary hypothesis, we anticipate that the highest clinical resolution rate of assigned active treatment will be uterine evacuation followed by medical management for some (active management strategy A) because this strategy will treat women with a miscarriage (with uterine evacuation) and will treat women with EP with MTX. The clinical resolution rate of empiric medical MTX management for all (active management strategy B) will be lower, as MTX is not always effective for management of a miscarriage (intrauterine pregnancy loss); a uterine evacuation may be required subsequently. If efficacy of active and expectant management is similar, or if the two active management strategies are similar, we will evaluate secondary outcomes and a cost-effective analysis. Financial costs and charge per procedure will be ascertained for this analysis using national averages. The cost effective analysis will be conducted from the perspective of the payer.

Discussion

The diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy has been streamlined in the past decade with protocols utilizing serial (hCG) levels and transvaginal ultrasound. The use of these protocols has likely contributed to the reduced tubal rupture, morbidity and mortality in women with an ectopic pregnancy [2, 8, 9]. However, a result of early and systematic evaluation of all women at risk is creation of a new conundrum: PPUL. We have demonstrated that up to 50% of women with a PPUL have an EP and 50% have a miscarriage based on performing a uterine evacuation to determine whether chorionic villi are present or absent in the uterine cavity [6]. Conversely, empiric treatment of a PPUL with MTX has been advocated to minimize surgical intervention, but may result in overuse of a chemotherapeutic medication. It is also possible that without a visualized ectopic pregnancy, the risk or rupture is low and expectant management may be the optimal strategy to minimize cost and morbidly [18]. Lack of objective data to inform clinicians as to the optimal strategy is an identified and universally accepted knowledge gap and a research priority [8, 9, 10, 11] and is the focus of this protocol.

We have designed the trial to be pragmatic to enhance recruitment and collect objective data to optimize the management strategy for PPULs. Although this study was performed under an IND for the evaluation of the two dose protocol of MTX for medical management of EP, the primary goal of the ACT or NOT trial is to compare management strategies for women presenting with a PPUL rather than the safety and efficacy of MTX.

All three management strategies in this randomized clinical trial are considered clinical standards of care; therefore, patients are not exposed to further ‘experimental’ risks. There is risk associated with the underlying clinical condition, including rupture of an undiagnosed ectopic pregnancy. Each of the management strategy has slightly different risks. Subjects randomized to expectant management may be at a higher risk for rupture of an ectopic pregnancy or retained miscarriage tissue, but such subjects avoid the morbidity associated with surgical and medical intervention. Subjects randomized to uterine evacuation, followed by MTX for some, will be exposed to the surgical risks of uterine evacuation (risk of bleeding, infection and uterine perforation), but may be spared the exposure, and morbidity associated with MTX (risk of nausea, abdominal pain, mouth sores). Subjects randomized to empiric MTX for all, may avoid the risk of uterine evacuation but are exposed to the risks of a chemotherapeutic medication.

Clinical care is often changed during the evaluation and treatment for women with a PPUL. Women may develop pain and bleeding necessitating clinical intervention or change in initial management strategy. Surgical intervention is often used as back up to MTX and/or expectant management. Moreover, a clinician and a woman often chose to deviate from initial strategy. However, mortality from a PPUL is very rare, thus ultimately all women are treated successfully (attain clinical resolution) even if initial treatment strategy changes based on clinical course or choice. Successful resolution of ectopic pregnancy or miscarriage could not be considered the primary outcome because when a PPUL is successfully treated with medical management, the underlying diagnosis cannot be distinguished. For these reasons, the primary outcome of the trial was a change in treatment strategy. While ruptured ectopic pregnancy is an important clinical outcome, its frequency is rare, and it will be considered a secondary outcome.

Conservative criteria were used for this trial. To ensure that there was no chance of enrolling (and intervening in) a woman with a potentially viable gestation we choose a threshold of less than 15% rise in hCG of a 24-hour period as the definition of nonviable, instead of the clinical standard of instead of less than 23% (4). The criteria for diagnosis of a non-visualized ectopic pregnancy was a decline of less than 15% after uterine evacuation. This threshold was chosen to maximize specificity and minimize use of methotrexate. A decline of 15% does not ensure that trophoblast was removed from the uterus after uterine evacuation. Surveillance of hCG until non detectable levels was part of the protocol, so that a plateau in the decline in hCG could be identified and treatment implemented.

Our primary analysis will be conducted according to the principal of intention to treat to obtain an objective measure of efficacy of each management strategy. However, it is anticipated the subjects and clinicians have opinions regarding the optimal management of a PPUL [19]. We plan to collect data on why the initial management strategy may be changed. Analysis of reasons for drop out (and drop in) will provide insight to clinician and patient choice. Above and beyond the success or failure of the initial treatment method, the clinical consequences and morbidity of interventions, the number of visits and tests, and the time to clinical resolution are also of great importance. Taking into account these factors, as well as cost, we plan to explore if expectant management may be less effective, but preferable. Alternatively, if efficacy is similar, we plan to compare which active strategy is preferable.

It is also anticipated that treatment outcomes may vary based on presenting signs and symptoms. We plan to assess efficacy and cost effectiveness in subgroups based on important covariates including initial level of (hCG), ultrasound findings suggestive of possible EP or miscarriage [7], estimated gestational age and the use of assisted reproductive technologies.

Conclusion

ACT-or-NOT is a randomized controlled clinical trial designed to determine if active management of women with a PPUL is superior to expectant management, and to determine if two common active management strategies of a women with a PPUL are non-inferior to each other. Ultimately, the ACT-or-NOT trial will provide important data to recommend optimal management strategy (ies) for women with a PPUL based on cost effectiveness, time to resolutions and patient satisfaction.

Figure 3:

Active Management B Flowchart: Methotrexate 2-dose protocol (20)

Acknowledgements

GRANT number for RMN 2U10HD055925 and R01HD076279 (KB)

The authors express their thanks to other members of the Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network (RMN) as well as the RMN Advisory Committee and Data Safety Monitoring Board for their clinical review of the ACT or NOT trial protocol.

We acknowledge investigators at recruiting sites:

| Augusta University | Michael Diamond | midiamond@augusta.edu |

| Carolinas Healthcare System | Rebecca Usadi | rebecca.usadi@carolinashealthcare.org |

| Eastern Virginia Medical School | Peter Takacs | takacsp@evms.edu |

| Greenville Health System | Benjie Mills | bmills@ghs.org |

| Penn State University | Richard Legro | rlegro@pennstatehealth.psu.edu |

| University of North Carolina | Anne Steiner | anne_steiner@med.unc.edu |

| University of Rochester | Kathleen Hoeger | kathy_hoeger@urmc.rochester.edu |

| University of San Francisco | Marcelle Cedars | Marcelle.Cedars@ucsf.edu |

| University of South Florida | Shayne Plosker | splosker@health.usf.edu |

| University of Utah | Erica Johnstone | erica.johnstone@hsc.utah.edu |

| Washington University | Emily Jungheim | jungheime@wustl.edu |

| Wayne State University | Stephen Krawetz | steve@compbio.med.wayne.edu |

Footnotes

Declaration of conflict of interest

All authors declared no actual or potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chow WH, Daling JR, Cates W Jr, Greenberg RS. Epidemiology of ectopic pregnancy. Epidemiol Rev 1987;9:70–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoover KW, Tao G, Kent CK. Trends in the diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancy. New Eng J Med 2009;361(4):379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeber B, Sammel M, Guo W, Zhou L, Hummel A, Barnhart KT. Application of redefined hCG curves for the diagnosis of women at risk for ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2006;86:454459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condous G, Okaro E, Khalid A, Lu C, Van Huffel S, Timmerman D, et al. The accuracy of transvaginal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy prior to surgery. Hum Reprod 2005;20(5):1404–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaunik A, Kulp J, Appleby DH, Sammel MD, Barnhart KT. Utility of dilation and curettage in the diagnosis of pregnancy of unknown location. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204(2):130.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnhart KT, van Mello N, Bourne T, Kirk E, Van Calster B, Bottomley C, Chung K, Condous G, Goldstein S, Hajenius P, Mol BW, Molinaro T, O’Flynn O’Brien K, Husicka R, Sammel M, Dirk Timmerman D. Pregnancy of unknown location: A consensus statement of nomenclature, definitions and outcome. Fertil Steril 2011;95(3):857–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACOG practice Bulletin “Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy” Obstetrics & Gynecology 131(3): 391–103 - 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK. “Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management in early pregnancy of ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage.” (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Fert Steril 2008;90(3):S206–212. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnhart KT. Early pregnancy failure: beware of the pitfalls of modern management. Fertil Steril 2012; 98: 1061–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid Shannon, and Condous George. “Is there a need to definitively diagnose the location of a pregnancy of unknown location? The case for “no”.” Fertility and sterility 985 (2012): 10851090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korhonen J, Stenman UH, Ylostalo P. Low dose oral methotrexate with expectant management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88(5):775–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elson J, Tailor A, Banerjee S, Salim R, Hillaby K, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of tubal ectopic pregnancy: prediction of successful outcome using decision tree analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004. June;23(6):552–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajenius PJ. The METEX study: methotrexate versus expectant management in women with ectopic pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 2008;8(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banerjee S, Aslam N, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Elson J, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of early pregnancies of unknown location: a prospective evaluation of methods to predict spontaneous resolutionof pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2001;108:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajenius PJ, Mol F, Mol BW, Bossuyt PM, Ankum WM, van der Veen F. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007:CD000324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Mello NM, Mol F, Verhoeve HR, Van Wely M, Adriaanse AH, Boss EA, Dijkman AB, Bayram N, Emanuel MH, Friedrerich J, van der Leeuw-Harmsen L, Lips JP, Van Kessel MA, Ankum WM, van der Veen F, Mol BW, Hajenius PJ. Methotrexate or expectant management in women with an ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy of unknown location and low serum hCG concentrations: A randomized comparison. Hum Reprod 2013; 28(1); 60–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parks M, Barnhart KT, Howard DL. Trends in the Management of Nonviable Pregnancies of Unknown Location in the Unities States. Gynecol Obstet Ivest 2018. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnhart KT, Hummel AC, Sammel MD, Menon S, Jain J, Chakhtoura N. Use of 2 dose regimen of methotrexate to treat ectopic pregnancy. Fert Steril 2007;87:250–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breskin A, Cole SR. Westreich D, Exploring the Subtleties of Inverse Probability Weighting and Marginal Structural Models. Epidemiology: 2018;29:352–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]