Abstract

Clostridium difficile infection is the most common cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in developed countries. The major virulence factor, C. difficile toxin B (TcdB), targets colonic epithelia by binding to frizzled (FZD) family of Wnt receptors, but how TcdB recognizes FZDs is unclear. Here we present the crystal structure of a TcdB fragment in complex with the cysteine-rich domain of human FZD2 at 2.5 Å resolution, which reveals an endogenous FZD-bound fatty acid acting as a co-receptor for TcdB binding. This lipid occupies the binding-site for Wnt-adducted palmitoleic acid in FZDs. TcdB binding locks the lipid in place, thereby preventing Wnt from engaging FZDs and signaling. Our findings establish a central role of fatty acids in FZD-mediated TcdB pathogenesis, and suggest strategies to modulate Wnt signaling.

One Sentence Summary:

C. difficile toxin B uses a lipid co-receptor to recognize frizzled proteins to achieve cell entry and antagonize Wnt signaling.

Clostridium difficile is an opportunistic pathogen that colonizes the colon in humans when the normal gut microbiome is disrupted. The infection leads to disruption of the colonic epithelial barrier, resulting in diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis and ~30,000 deaths annually in the US alone (1–5). The diseases associated with C. difficile infection (CDI) are caused by two C. difficile exotoxins, toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB), which act as glucosyltransferases to inactivate small GTPases leading to actin cytoskeleton disruption and cell death (3, 6–8). Of the two toxins, TcdB alone is capable of causing the full-spectrum of diseases in humans, as TcdA−TcdB+ strains have been clinically isolated (9–12). Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4), poliovirus receptor-like 3 (PVRL3), and frizzled proteins (FZDs) have been recently identified as TcdB receptors (13–16), with FZDs thought to be the major receptors in the colonic epithelium (13, 17). FZDs are a family of transmembrane receptors for lipid-modified Wnt morphogens (18, 19). Binding of TcdB to FZDs, especially FZD1, 2 and 7, not only mediates toxin entry, but also inhibits Wnt signaling that regulates self-renewal of colonic stem cells and differentiation of the colonic epithelium (13, 20, 21). The mechanism by which TcdB specifically recognizes FZDs and inhibits Wnt signaling is unknown.

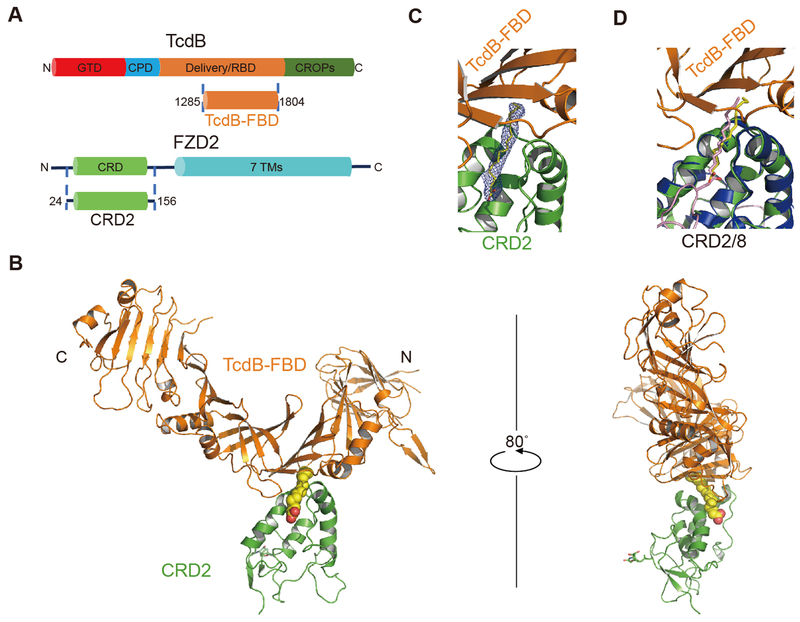

TcdB is a large multi-domain protein (~270 kDa) (Fig. 1A). We first screened and characterized a series of TcdB truncations and narrowed down a short TcdB fragment (residues 1285-1804), referred to as the FZD-binding domain (TcdB-FBD) (Table S1), which robustly binds to the cysteine-rich domain of FZD2 (residues 24-156, referred to as CRD2). Bio-layer interferometry (BLI) analysis confirmed that TcdB-FBD binds to CRD2 with an affinity (dissociation constant, KD ~13 nM) similar to that of full-length TcdB (KD ~19 nM) (fig. S1, A and F) (13). We determined the co-crystal structure of TcdB-FBD in complex with human CRD2 at 2.5 Å resolution, using TcdB-FBD produced in E. coli and CRD2 produced as a secreted protein from human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells (Table S2). The structure reveals one TcdB-FBD-CRD2 complex in an asymmetric unit, with a total buried interface of ~1488 Å2 (Fig. 1B). CRD2 adopts the conserved CRD fold with four α helices and two β strands stabilized by five disulfide bridges. The comparison between CRD2 and FZD7-CRD (PDB: 5URV) and FZD8-CRD (PDB: 4F0A) yielded root-mean-square deviations of ~0.62 Å and ~1.13 Å, respectively (22, 23). TcdB-FBD adopts an L-shape with its vertex bound by CRD2, and the overall structure of TcdB-FBD is similar to the homologous region in TcdA (Fig. 1B, and fig. S2, A and B) (24).

Fig. 1. Overall structure of TcdB-FBD in complex with CRD2.

(A) Schematic diagrams showing the domain structures of TcdB and FZD2, as well as the two interacting fragments used in this study. GTD: glucosyltransferase domain; CPD: cysteine protease domain; Delivery/RBD: delivery and receptor-binding domain; CROPs: combined repetitive oligopeptides domain; CRD: cysteine-rich domain; 7TMs: 7 transmembrane helices. (B) Cartoon representation of the complex with TcdB-FBD in orange, CRD2 in green, and PAM in a yellow sphere model. An N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG) due to N-linked glycosylation on CRD2-N53 is shown as sticks. (C) Electron density of the PAM bound between TcdB-FBD and CRD2. An omit electron density map contoured at 2.5 σ was overlaid with the final refined model. (D) The PAM molecules bound in the TcdB-FBD-CRD2 and the Wnt8-CRD8 (Wnt8 and CRD8 are colored purple and blue, respectively) complexes are shown as yellow and purple sticks, respectively, when the two complexes are superimposed based on CRD2 and CRD8.

A 16-Å long cylinder-like electron density was observed in a hydrophobic groove in CRD2, which is completely buried between TcdB-FBD and CRD2 (Fig. 1C). The homologous groove in CRD8 binds a palmitoleic acid (PAM) lipid modification of Wnt8, a conserved post-translational modification crucial for Wnt signaling (23, 25, 26). The PAM molecule seen in the structure of the CRD8-Wnt8 complex matches the electron density pattern in the hydrophobic pocket between TcdB-FBD and CRD2 (Fig. 1C) (23). We assume that this PAM was co-purified with CRD2 from HEK cells, although we could not unambiguously determine whether it is palmitoleic or palmitic acid.

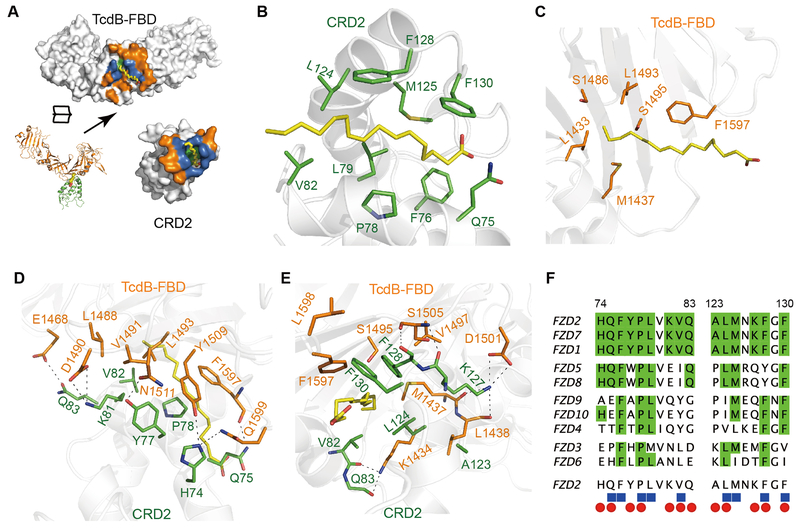

This PAM is bound by both CRD2 and TcdB-FBD (Fig. 2A). CRD2 binds to PAM mainly through hydrophobic interactions: residues Q75, F76, M125, and F130 stabilize PAM from the side of its carboxylic group, and residues P78, L79, V82, L124 and F128 stabilize the middle of PAM’s hydrocarbon chain (Fig. 2B). This binding mode is similar to how Wnt PAM is stabilized in CRD8 (23). The tail of the PAM acyl chain and some hydrophobic PAM-binding residues in CRD8 are exposed to solvent. Interestingly, in the CRD2 complex these hydrophobic patches, which are energetically suboptimal in an aqueous environment, are fully shielded by TcdB-FBD. Specifically, F1597 of TcdB stabilizes the middle part of PAM, while residues L1433, M1437, S1486, L1493, and S1495 (together with V82 and L124 of CRD2) form a hydrophobic pocket to cap the PAM tail protruding from the CRD2 groove (Fig. 2, B and C). This PAM is therefore completely buried involving ~580 Å2 and ~320 Å2 of surface areas with CRD2 and TcdB-FBD, respectively. Besides PAM-mediated interactions, TcdB-FBD engages CRD2 directly through an extensive network of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions surrounding the lipid-binding groove, which likely provides the major driving force for assembling the complex (Fig. 2, D and E, and Table S3). Many of these residues involved in protein-protein interactions also participate in PAM binding, suggesting that binding between TcdB-FBD and CRD is synergistically mediated by both proteins and PAM (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2. TcdB-FBD recognizes CRD2 through combined fatty acid- and protein-mediated interactions.

(A) An open-book view of the TcdB-FBD-CRD2 interface. Residues that participate in protein-protein, protein-lipid, or both are colored orange, green, and blue, respectively. (B and C) A PAM molecule simultaneously interacts with CRD2 (B) and TcdB-FBD (C). Key PAM-binding residues and PAM are shown as stick models. (D and E) Two neighboring protein-mediated interfaces between TcdB-FBD and CRD2, which surround the lipid-binding groove in CRD2. (F) Amino acid sequence alignment among the ten human FZDs within the TcdB-FBD-interacting region. Invariable residues are colored green. CRD2 residues that bind to PAM and TcdB-FBD are labeled as blue cubes and red ovals, respectively.

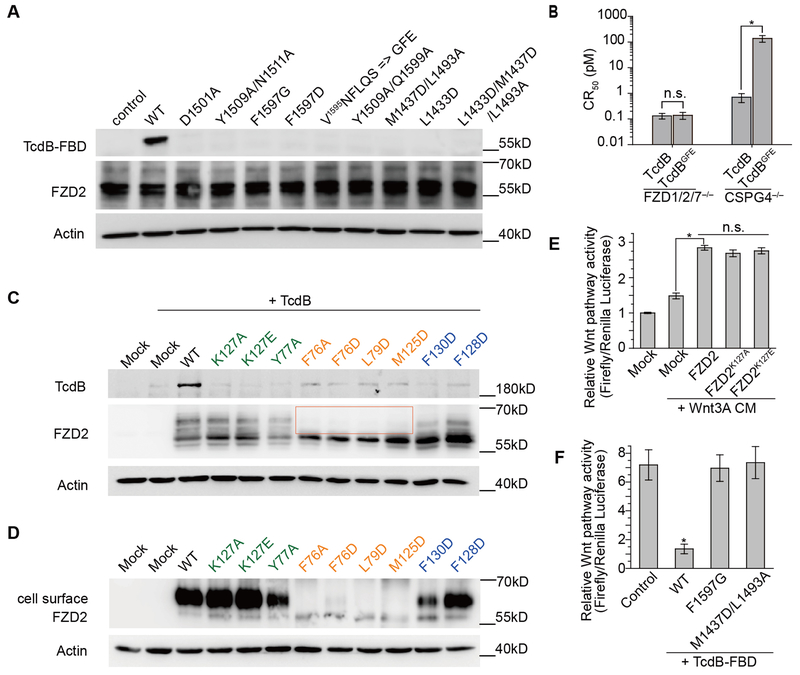

To further probe the TcdB-FBD-lipid-FZD binding specificity, we examined binding of selected site-specific mutants of TcdB-FBD to FZDs. We first examined binding of TcdB-FBD variants to immobilized His- or Fc-tagged CRD2 using pull-down assays (fig. S3A) or BLI assays (fig. S1). No exogenous PAM was added in either assays. TcdB-FBD variants carrying mutations that disrupt binding to both PAM and CRD2 (e.g., F1597G, F1597D, M1437D/L1493A, and L1433D/M1437D/L1493A) did not yield detectable binding in either pull-down or BLI assays (KD > 10 μM). Mutations at the protein-protein interface (e.g., D1501A, Y1509A/N1511A, and Y1509A/Q1599A) significantly weakened the TcdB-FBD-CRD2 binding affinity by ~43–138 fold compared to wild type (WT) TcdB-FBD (fig. S1F). A single point mutation (L1433D) disrupting a hydrophobic pocket in TcdB that accommodates the distal acyl tail of PAM also decreased the binding to CRD2 by ~37 fold. None of these TcdB-FBD variants interfere with protein folding as verified by a thermal shift assay (fig. S4). We then examined binding of TcdB-FBD variants to HeLa cells transiently transfected with full-length FZD2 (Fig. 3A) or stably expressed GPI-anchored FZD7-CRD (fig. S3, B and C). TcdB-FBD variants did not show detectable binding to FZD2 or FZD7-CRD-GPI at the concentration tested (50 nM), while WT TcdB-FBD bound robustly to these cells. The pull-down (fig. S3A) and the BLI (fig. S1) assays were more sensitive than the cell-based assays (Fig. 3A and fig. S3C) in detecting weak interactions between CRD2 and TcdB-FBD variants, likely as a result of relatively low concentrations of FZD2/7 expressed on the cell surface. The mutagenesis studies thus verify the structural findings and suggest that TcdB exploits a free fatty acid as the co-receptor to engage FZDs.

Fig. 3. Structure-based mutagenesis analyses of the interactions between TcdB and FZD2.

(A) Mutations in TcdB-FBD that disrupt its interactions with PAM and/or CRD2 impaired TcdB-FBD (50 nM) binding to HeLa cells overexpressing FZD2. (B) The sensitivity of FZD1/2/7 triple KO HeLa cells and CSPG4 KO HeLa cells to full length WT TcdB and TcdBGFE was determined by cell-rounding assays. CR50 is defined as the toxin concentration that induces 50% of cells to become round in 24 hours. (C) When expressed in HeLa cells, WT FZD2 but not the mutated variants mediated robust binding of full-length TcdB (10 nM) on cell surfaces. Mutations in CRD2 that are located in the protein-protein interface with TcdB, in the core lipid-binding groove, or at the edge of the lipid-binding groove are marked in green, orange, and blue, respectively. Four FZD2 variants lacking detectable levels of glycosylation are highlighted in a box. (D) These four FZD2 variants failed to reach cell surfaces as examined by detecting biotinylated FZD2 on cell surfaces. (E) FZD2-K127A/E were capable of mediating Wnt signaling to a level similar to WT FZD2. (F) WT TcdB-FBD, but not the mutated variants (F1597G and M1437D/L1493A), inhibited signaling by Wnt3A CM in HEK293T cells as measured by the TOPFLASH reporter assay. Data are mean ± s.d., n=6, *p<0.01, Mann-Whitney Test (B and F) or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA (E).

The CRD2- or PAM-interacting residues in TcdB are not conserved in TcdA (fig. S2C), explaining the unresponsiveness of FZDs to TcdA (13). In particular, we found that TcdA and TcdB are distinct in a small area that contain three residues (F1597, L1598, and Q1599) that bind to PAM and CRD2 (fig. S2C). When we replaced this region in TcdB-FBD (1595VNFLQS) with the corresponding residues in TcdA (1596GFE), the mutated TcdB-FBD could no longer bind FZD2, confirming the importance of this region in TcdB for FZD binding (Fig. 3A, fig. S1F, and fig. S3A). We then generated a full length TcdB carrying the same mutations that abolish FZD binding (termed TcdBGFE) and used it as a molecular tool to determine the physiological relevance of FZDs and lipids to the toxicity of TcdB. We first validated the activity of TcdBGFE using a cell-rounding assay (CR50) on FZD1/2/7 KO HeLa cells, which still express a high level of CSPG4 that could mediate toxin entry (13). As shown in Fig. 3B, TcdBGFE and WT TcdB displayed a similar toxicity on FZD1/2/7 KO HeLa cells, indicating that TcdBGFE was properly folded. To separate the contribution of CSPG4 and FZDs to toxin cell entry, we further tested the activity of TcdBGFE and WT TcdB on CSPG4 KO HeLa cells. Indeed, FZD-binding deficient TcdBGFE displayed a ~190 fold reduced toxicity compared to the WT toxin, demonstrating the functional role of FZDs in mediating TcdB binding and entry into cells (Fig. 3B).

The binding site for the lipid co-receptor in FZDs also accommodates the Wnt PAM or exogenous lipids in vitro (22, 27). Do FZDs bind free fatty acids in vivo and if so what are their functions? To answer these questions, we designed mutations to selectively disrupt the core of the lipid-binding groove in CRD2 (e.g., F76A, F76D, L79D, and M125D), and expressed the corresponding full-length mouse FZD2 in CSPG4 KO HeLa cells (residue numbering is based on human FZD2 sequence). The use of CSPG4 KO HeLa cells also allows us to examine the interactions between these lipid-binding deficient FZD2 variants and TcdB. While all four FZD2 variants were expressed in cells, they lacked detectable levels of glycosylation (Fig. 3C). Surface biotinylation assays confirmed that these four variants failed to reach the cell surface (Fig. 3D). In comparison, mutating CRD2 residues in the protein-protein interface with TcdB-FBD (e.g., K127A, K127E, and Y77A) or residues at the edge of the lipid-binding groove (e.g., F128D and F130D) did not significantly alter FZD2 glycosylation and surface expression. We also confirmed that FZD2-K127A/E mediated similar levels of Wnt signaling as WT FZD2 did in cells, demonstrating that they were correctly folded (Fig. 3E, and fig. S5, A and B). These results thus suggest that binding of an endogenous free fatty acid in CRD2 is crucial for proper folding, glycosylation, and/or trafficking of FZD2, providing evidence for the existence and significance of free lipid-FZD interaction in a physiological context. Furthermore, none of these FZD2 variants mediated binding of full-length TcdB when expressed in CSPG4 KO HeLa cells (Fig. 3C), further illustrating the role of FZDs as TcdB receptors.

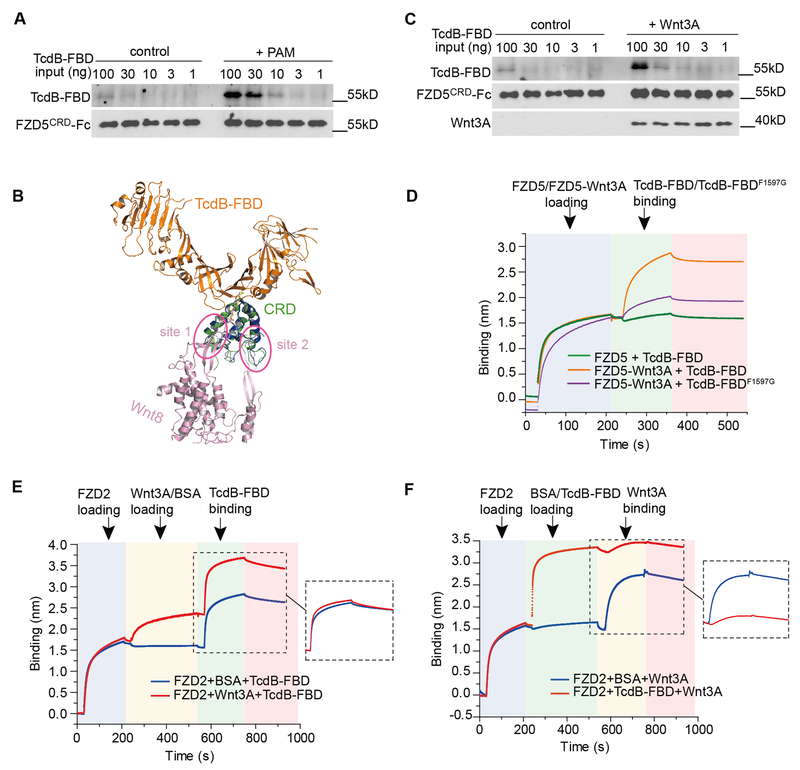

Besides FZD1, 2, and 7, which are high affinity receptors for TcdB (13), other FZDs likely also bind endogenous fatty acids, because the hydrophobic lipid-binding groove in CRD2 is largely conserved across all 10 members of FZDs (Fig. 2F). But subtle amino acid differences in this groove or the neighboring region may influence how tightly a fatty acid binds to a CRD. For example, recombinant CRD5 does not contain a free fatty acid, which may have dissociated during CRD5 purification, but it could bind exogenous PAM provided in solution (22). We confirmed that CRD5 by itself only weakly pulled down TcdB-FBD, but pre-incubation of CRD5 with PAM significantly increased its binding to TcdB-FBD (Fig. 4A). This “gain-of-function” for CRD5 to bind TcdB-FBD aided by the free PAM further supports the notion that a CRD-bound fatty acid is a critical co-receptor for TcdB. Our data suggest that the affinity and specificity of different FZDs towards TcdB are likely determined by a combination of their interactions with free fatty acids, as well as their specific protein-protein contacts with TcdB. For instance, residues Y77, K81, V82, A123 and K127 of CRD2 that contact TcdB are only conserved in FZD1, 2, and 7 (Fig. 2F). Disrupting such protein-protein interactions in FZD2 (e.g., Y77A and K127A/E) greatly decreased binding by full-length TcdB when expressed in CSPG4 KO HeLa cells (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 4. A free fatty acid facilitates binding of TcdB to FZD-CRDs, which in turn prevents docking of the Wnt PAM.

(A) Pre-loading FZD5-CRD with PAM enhanced its binding to TcdB-FBD based on pull-down assays. (B) Superimposed structures of the TcdB-FBD-CRD2 and the Wnt8-CRD8 complexes. The two distinct interfaces between Wnt8 (purple) and CRD8 (blue) are highlighted in circles (site 1 & 2). (C and D) Pre-loading Wnt3A to FZD5-CRD enhanced its binding to TcdB-FBD based on pull-down assays (C) and BLI assays (D). The enhancement was minimal for TcdB-FBD-F1597G. Sequential loading of different proteins to the biosensor and binding dissociation are indicated by different background colors. (E) Pre-loading Wnt3A to CRD2 did not interfere with subsequent binding of TcdB-FBD. (F) Pre-loading CRD2 with TcdB-FBD impeded subsequent binding of Wnt3A.

It is well established that Wnt binds to FZD-CRD via the Wnt PAM as a major driving force (18, 21, 23). The Wnt PAM occupies the same hydrophobic groove in CRD as the free lipid (Fig. 1D). We found that TcdB-FBD can bind to the Wnt-FZD complex using the Wnt PAM as a co-receptor, as TcdB-FBD engages CRD2 from the opposite side of the Wnt-binding interface without direct steric competition with Wnt (Fig. 4B). The ability to recognize Wnt-bound FZDs is perhaps particularly advantageous for TcdB to recognize certain FZDs that may have weaker affinities for free lipids. Indeed, we found that pre-incubation of Wnt3A with CRD5 enhanced binding of TcdB-FBD to CRD5 in pull-down and BLI assays, whereas the enhancement was dramatically reduced for TcdB-FBD-F1597G (Fig. 4, C and D). Similar Wnt-mediated enhancement was also observed for three other CRDs (human FZD4, FZD8, and FZD9) (fig. S6, A-C), and was further confirmed using full-length TcdB and CRD5 (fig. S6D). Thus TcdB can use the Wnt PAM, a conserved Wnt posttranslational modification, as a co-receptor to recognize a broad range of FZDs despite their sequence variations.

CRD2 and the pre-formed CRD2-Wnt3A complex were recognized equally well by TcdB-FBD or full-length TcdB (Fig. 4E and fig. S7A). This suggests that either the free lipid or the Wnt PAM supports TcdB binding to CRD2. In contrast, upon binding to TcdB-FBD or full-length TcdB, CRD2 could no longer bind Wnt3A (Fig. 4F and fig. S7B). This is likely because the Wnt PAM cannot displace the free fatty acid once it is locked in place by TcdB. This is consistent with the observation that TcdB-FBD blocked Wnt3A-induced signaling in cells, while the CRD-binding deficient TcdB-FBD variants did not (Fig. 3F, and fig. S5, C and D). Recent studies suggested that Wnt PAM may contribute to CRD dimerization, although the contribution of such FZD dimerization to activate Wnt signaling remains to be fully established (22, 27). Two different CRD dimer configurations have been reported (fig. S8A) (22, 27). Binding of TcdB, or TcdB-FBD, would prevent CRD dimerization in either configuration due to steric competitions, which may also contribute to Wnt signaling inhibition (fig. S8B).

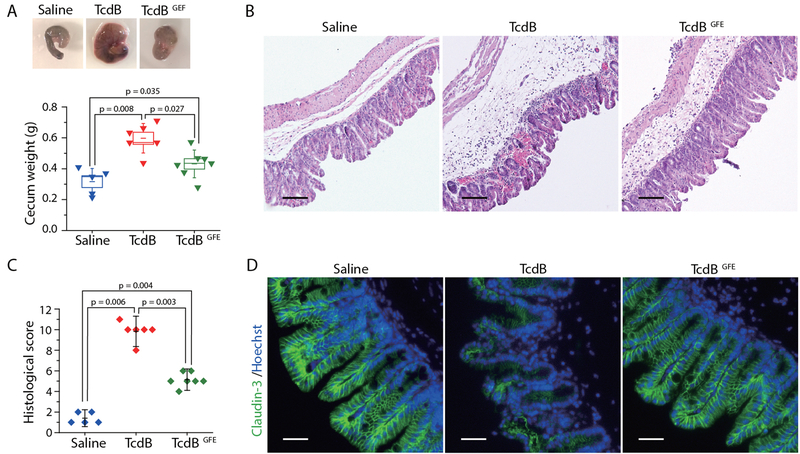

Given our extensive in vitro and ex vivo data demonstrating the role of FZDs and the FZD-bound fatty acids as TcdB receptors, we sought to determine the physiological relevance of TcdB-lipid-FZD interactions to the toxicity of TcdB in vivo. Colonic tissues are the pathological relevant target tissue for TcdB. It has been shown that FZDs are major receptors in the colonic epithelium, while CSPG4 is expressed in the sub-epithelial myofibroblasts but not colonic epithelium (13). We therefore used a murine cecum injection model, which has been previously utilized to assess TcdB-induced damage to colonic tissues (28, 29). Briefly, a full length FZD-binding deficient TcdB variant, TcdBGFE (Fig. 3B), the WT TcdB, or the control saline solution was injected into cecum of WT mice. Mice were allowed to recover and cecum tissues were harvested 12 h later for analysis. WT TcdB induced severe bloody fluid accumulation and vesicular congestion in the cecum, resulting in drastic swelling as expected. In contrast, TcdBGFE induced much less fluid accumulation and no obvious vesicular congestion (Fig. 5A). To further examine the damage to tissues, we carried out histological analysis with paraffin embedded cecum tissue sections. These tissues were scored based on four histological criteria, including disruption of the epithelium, hemorrhagic congestion, mucosal edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration, on a scale of 0 to 3 (normal, mild, moderate, or severe). WT TcdB induced extensive disruption of the epithelium and inflammatory cell infiltration, as well as severe hemorrhagic congestion and mucosal edema, while TcdBGFE induced much less damage on all four criteria (Fig. 5B, C). We further assessed the integrity of epithelial tight junction by immunofluorescent staining for tight junction marker Claudin-3. WT TcdB induced extensive loss of Claudin-3 in the epithelium, while the overall morphology of the epithelial tight junction was not changed after treatment with TcdBGFE (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data further prove that FZDs are the major pathologically relevant receptors for TcdB in the colonic tissues.

Fig. 5. FZDs and the FZD-bound fatty acids are the major pathologically relevant receptors for TcdB in the colonic tissues.

(A) WT TcdB (15 μg), TcdBGFE (15 μg) or the saline control was injected into the cecum of WT mice in vivo. The cecum tissues were harvested 12 hours later. The representative cecum tissues were shown, and the weight of each cecum was measured and plotted. (Boxes represent mean ± standard error of the mean, s.e.m.), and the bars represent s.d., Mann-Whitney). (B, C) Cecum tissue sections were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The representative images were shown in panel B. The histological scores (panel C) were assessed based on disruption of the epithelia, hemorrhagic congestion, mucosal edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration. (Data are mean ± s.d., Mann-Whitney). Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Immunofluorescent staining of epithelial cell junction marker Claudin-3 (green) in ceca from mice injected with saline, TcdB, or TcdBGFE (blue indicates cell nuclei). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Wnt signaling is critical for development, tissue homeostasis, stem cell biology, and many other processes, and its malfunction is implicated in diseases including a variety of human cancers and degenerative diseases (21, 30). The FZD-antagonizing mechanism exploited by TcdB turns a toxin into a potential pharmacological tool for research and therapeutic applications. The unexpected fatty acid-dependent binding of TcdB to FZDs also exposes a vulnerability of TcdB, which could be exploited to develop novel antitoxins that block toxin-receptor recognition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was partly supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R01AI091823, R01 AI125704, and R21AI123920 to R.J.; R01 NS080833 and R01 AI132387 to M.D; and R01GM057603 and R01GM126120 to X.H. M.D. and X.H. also acknowledge support by the Harvard Digestive Disease Center (NIH P30DK034854) and Boston Children’s Hospital Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (NIH P30HD18655). M.D. holds the Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. X.H. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor. NE-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) is supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C beam line is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205). Use of the APS, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Author contributions: M.D. and R.J. conceived the project. P.C., T.W., K.L., Z.L., and R.J. carried out the protein expression, purification, characterization, structure determination and analysis, and structure based mutagenesis. L.T., A.H., J.Z., and M.D. performed structure-based mutagenesis, all the functional characterization, and BLI binding studies. K.P. collected the X-ray diffraction data. X.H. helped with Wnt signaling assays and provided advice. P.C., L.T., M.D., and R.J. wrote the manuscript with input from other authors. Competing interest: All authors declare no competing interests. Data and materials availability: Coordinates and structure factors of the TcdB-FBD-CRD2 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 6C0B. All other data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary materials. A provisional patent application on utilizing TcdB-FBD to modulate Wnt signaling has been filed jointly by Boston Children’s Hospital and University of California Irvine.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Figures S1-S11

Tables S1-S3

References (31-36)

References and Notes:

- 1.Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 526–536 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinlen L, Ballard JD, Am J Med Sci 340, 247–252 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voth DE, Ballard JD, Clin Microbiol Rev 18, 247–263 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt JJ, Ballard JD, Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77, 567–581 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smits WK, Lyras D, Lacy DB, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ, Nat Rev Dis Primers 2, 16020 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jank T, Aktories K, Trends Microbiol 16, 222–229 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun X, Savidge T, Feng H, Toxins (Basel) 2, 1848–1880 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pruitt RN, Lacy DB, Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2, 28 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drudy D, Fanning S, Kyne L, Int J Infect Dis 11, 5–10 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyras D et al. , Nature 458, 1176–1179 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuehne SA et al. , Nature, (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter GP et al. , MBio 6, e00551 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao L et al. , Nature 538, 350–355 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan P et al. , Cell Res 25, 157–168 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaFrance ME et al. , Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 7073–7078 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta P et al. , J Biol Chem 292, 17290–17301 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terada N et al. , Histochem Cell Biol 126, 483–490 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald BT, He X, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Chang H, Rattner A, Nathans J, Curr Top Dev Biol 117, 113–139 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregorieff A, Clevers H, Genes Dev 19, 877–890 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nusse R, Clevers H, Cell 169, 985–999 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nile AH, Mukund S, Stanger K, Wang W, Hannoush RN, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 4147–4152 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC, Science 337, 59–64 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chumbler NM et al. , Nat Microbiol 1, 15002 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takada R et al. , Dev Cell 11, 791–801 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willert K et al. , Nature 423, 448–452 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeBruine ZJ et al. , Genes Dev 31, 916–926 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y et al. , Anaerobe 48, 249–256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Auria KM et al. , Infect Immun 81, 3814–3824 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinhart Z et al. , Nature medicine 23, 60–68 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabsch W, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams PD et al. , Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunger AT, Nature 355, 472–475 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen VB et al. , Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 12–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang G et al. , BMC Microbiol 8, 192 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.