Abstract

Objectives

Involving patients in quality improvement is often suggested as a critical step for improving healthcare processes. However, this comes with challenges related to resources, tokenism, validity and competence. Therefore, to optimise the use of available resources, there is a need to understand at what stage in the improvement cycle patient involvement is most beneficial. Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify the phase of an improvement cycle in which patient involvement had the highest impact on radicality of improvement.

Design

An exploratory cross-sectional survey was used.

Setting and methods

A questionnaire was completed by 155 Swedish healthcare professionals (response rate 34%) who had trained and had experience in patient involvement in quality improvement. Based on their replies, the impact of patient involvement on radicality in various phases of the improvement cycle was modelled using the partial least squares method.

Results

Patient involvement in quality improvement might help to identify and realise innovative solutions; however, there is variation in the impact of patient involvement on perceived radicality depending on the phase in which patients become involved. The highest impact on radicality was observed in the phases of capture experiences and taking action, while a moderate impact was observed in the evaluate phase. The lowest impact was observed in the identify and prioritise phase.

Conclusions

Involving patients in improvement projects can enhance the quality of care and help to identify radically new ways of delivering care. This study shows that it is possible to suggest at what point in an improvement cycle patient involvement has the highest impact, which will enable more efficient use of the resources available for patient involvement.

Keywords: quality in health care, organisational development, change management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The research team has practical and academic experience from both healthcare and quality improvement.

Radicality has been sparsely used as a measure for patient involvement in quality improvement.

The model allows for a prioritising of when to involve patients in improvement projects.

Patients were not asked the same questions as healthcare professionals to validate results.

How the impact of patient involvement on radicality might be affected by the type of healthcare setting was not examined.

Background

Healthcare today faces an imminent challenge originating from the paradox of survival—namely, a higher demand for care without additional budget.1 Stretching available resources to cover more individuals while simultaneously pursuing new possibilities for treatment often using expensive methods has demanded radical changes in the organisation and improvement of existing healthcare systems. As a response to this challenge, patient involvement in quality improvement (QI) has increasingly been viewed as a means to generate more radical ideas for new healthcare services.2–5 Radicality can be defined as the potential or novelty of a QI idea for meeting new needs of patients, thus generating solutions or innovations that range from incremental (‘the same but better’) to radical (‘really different’).6 7 Note that radicality does not necessarily refer to solutions that are new to the world, but solutions that allow for addressing previously unmet patient needs within specific contexts.

The notion of patient involvement includes a variety of influences that has led to its development, including democratisation, challenges to professional power and welfare rights social movements. It is also believed that patient involvement can lead to radically new and more resource-efficient ways of delivering healthcare.1 These changes do not necessarily need to be on a large scale, it is often small things that can be questioned and pointed out by patients that can lead to effective new ways of working. To generate radical as opposed to incremental innovation, there needs to be a sense of urgency and a tension for change.8 The fundament for the creation of a sense of urgency is a disconfirmation of taken-for-granted implicit assumptions. Potentially, this leads to organisational members experiencing the current conditions as inadequate and developing motivation for change. Using patients’ experiences wisely (ie, for the right purpose at the right time) can contribute to such a tension for change. For example, methods that involve customers in design activity9 emphasise the need for coping with conflicting interests; thus, when staff is exposed to patients’ first-hand experiences, this provides an insight into the need for change, that is, it intensifies the tension for change. However, the impact of patient involvement on radicality per se has been questioned, and arguments have been put forth that patient involvement lends itself to more incremental rather than radical change.9

Patient involvement has been criticised for being exclusive and cosmetic, and for tokenism.2 10 11 Furthermore, efforts to achieve greater involvement have been patchy and slow as healthcare QI personnel experience several obstacles and sometimes even do not value patient involvement at all. It cannot be neglected that patient involvement imposes challenges in terms of resources,12 tokenism,13 14 validity15 and competence.16 First, involving patients is time and resource consuming,15 and requires careful management to reach its full potential.10 Second, if patients are asked but not listened to, tokenism might ensue in order to simply ‘tick the boxes’,14 with hierarchical structures and asymmetrical patterns of power remaining unchallenged.13 17 Third, there might be validity issues with patient involvement studies and therefore, more rigorous evidence of their outcome is desirable for such studies to be confirmed and accepted as high-quality research. Finally, in terms of competence, Batalden et al 12 stressed that each level of shared work in cocreation between staff and patients requires specific knowledge of the subject matter, know how, dispositions and behaviours, thus pointing to a need for healthcare competence in QI work.

Despite these challenges, there are promising examples of patient involvement in QI, for example, in acute care,18 development of patient education materials17 and neonatal care.19 The positive effects of patient involvement include enabling patients to act as intermediaries between other patients and clinicians, which may help to convince healthcare professionals of a need for change.10 Additionally, patient involvement may improve care efficiency and decrease costs, among other aspects.10 However, overall, there is rather poor-quality evidence and few measurements to evaluate the impact of patient involvement.10 20 21

Thus, there are contradictory views on the potential of patient involvement to contribute to radical improvements in healthcare. A reason for this controversy lies in the uncertainty regarding how to work with patient involvement,2 in particular in terms of the most beneficial stage to involve patients in QI. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to identify the phase of an improvement cycle in which patient involvement had the highest impact on the radicality of the improvement. This will aid in the optimisation of resource allocation to best support the contributions of patient involvement to radically new and improved ways of organising and delivering healthcare. For this purpose, we evaluated when patient involvement is most beneficial in an improvement cycle, which we divided into four phases according to the work of Bate and Robert22: capture experiences, identify and prioritise, taking action and evaluate. These four phases are also generally found in other forms of patient involvement in QI cycles.8 The first phase involves capturing patient experiences, for example, through interviews, films and diaries. The second phase involves identifying and prioritising areas for improvement in the care process. Active involvement in QI is considered to comprise the third phase, taking action, while in the fourth phase, evaluate, patients can be involved in the follow-up and evaluation of improvements.22 23

Methods

Sample

Data were collected through an online cross-sectional survey using a web-based survey tool provided by FluidSurveys.com. The original sample consisted of 472 participants who had training and practical experience in patient involvement in QI. The training ranged from a 2-week course to a 2-year part-time university education. All training consisted of a combination of theoretical elements (focusing QI and patient involvement in healthcare) as well as practical improvement projects. Regarding the practical experience of QI and patient involvement (besides the projects being part of the training), the experience ranged from 1 to more than 10 completed projects; the projects focusing, for example, the eating environment at hospitals, decreasing compulsory care in psychiatry and improvements in cancer care. The sampling frame was given by access to email lists from three of the largest providers of courses on QI in healthcare, the email lists included all their previous participants

The participants came from several Swedish healthcare regions, responsible for the provision of primary care, healthcare and dental care in a specific geographical area. Nineteen additional participants were added by using snowball sampling. In total, 491 participants were included and received an email with an introductory message and a link to the survey. Following two email reminders, 155 participants completed the entire questionnaire (response rate 32%). However, a number of participants (n=32) no longer worked in healthcare or were unable to answer the questionnaire for various reasons (eg, long sick leave); after excluding these individuals from the original sample, the adjusted response rate was 34%. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical code of research in healthcare.24

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients were not included in the sampling for this study. It is considered appropriate25 26 for evaluation of improvement projects to choose people with a long track record of experience with a specific process, in our case the QI-staff. Patients have invaluable knowledge of the experience from other dimensions, but have less knowledge about the organisation, and what can be considered as radical might thereby have a completely different meaning than for the QI personnel and should therefore not be compared.

Measures

The questionnaire comprised a cover letter and 44 questions. The questions were based on three validated questionnaires on the evaluation of improvement initiatives,27 experience-based codesign28 and customer involvement in service innovation.29 The first questionnaire27 was chosen because it examines how improvement projects can be evaluated, the second28 investigates how to evaluate patient involvement in improvement projects specifically and the third questionnaire29 examines how to study radicality of improvements in a service area. Most of the questions were close ended (examples can be seen in table 1), with a few being open ended and covered: the participants’ demographic and background information, motivation and organisation of improvement projects, experiences of patient involvement in QI, the organisational culture and the perceived results of patient involvement in QI. A pilot questionnaire was evaluated by a focus group consisting of five healthcare professionals from different healthcare organisations with training and practical experience in patient involvement in QI. This contributed to clarifications of questions and instructions in the survey, and ensured an understanding of the survey and its item among the focus group participants.

Table 1.

Latent variables, items and scale

| Latent variable/phase of improvement cycle | Items | Acronym | Scale |

| Capture experiences | To what extent did patients/relatives participate in capturing experiences about the process? | Sharing experiences | 5-point scale from 1 (to a small degree) to 5 (to a large degree) |

| To what extent did patients/relatives participate in the identification of improvement areas? | Identifying improvement areas | ||

| Identify and prioritise | To what extent did patients/relatives participate in the planning of the quality improvement project? | Project planning | |

| To what extent did patients/relatives participate in prioritising possible improvement areas? | Prioritising | ||

| Taking actions | To what extent did patient/relatives participate in generating improvement suggestions? | Generating suggestions | |

| To what extent did patient/relatives participate in the implementation of improvement suggestions? | Implementing suggestions | ||

| Evaluate | To what extent did patient/relatives participate in the evaluation of the results of the quality improvement project? | Evaluating results |

Seven items were used to operationalise the independent latent constructs of the phases of an improvement cycle (table 1).

The dependent variable—radicality of improvement—was measured using a self-report single-item measure: ‘To what extent do you agree with the following statement: with the new way of working (resulting from the QI project) we can meet patient needs that we did not try to meet earlier’, building on Cooper.30 The item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (fully agree). Radicality hence focuses on the potential of the new way of working to meet prior unmet patient needs. This is similar to the definitions of radical innovations proposed by Tidd and Bessant31 and Hertog et al.32

Data analysis

This study was exploratory and relied on a formative measure of radicality of improvement, for which the partial least squares (PLS) method is well suited.33 Moreover, the PLS method can be used in situations where there could be strong correlations between items,29 as could be the case in this study. The validity of the model was checked by examining the average variance extracted (AVE),34 which measures the relation between the variance captured by the construct and the variance caused by measurement error.35 Good discriminant validity in PLS is established if the off-diagonal values are lower than the diagonal values.29

Results

The participants in this study all had training as well as experience of QI involving patients, moreover 63.9% of the participants reported that they had experiences as facilitators of projects with patient involvement. One participant reported being involved in an improvement project involving patient conducted already in 1979, but most of the mentioned projects were conducted after year 2010. The participants represented a variety of professions; the distribution of gender and occupation of the participants is shown in table 2. The distributions of gender and professions are in line with the total distributions in Swedish healthcare.

Table 2.

Characteristics of respondents (n=155)

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 117 (75.5) |

| Male | 36 (23.2) |

| Missing data | 2 (1.3) |

| Profession, n (%) | |

| Nurse | 71 (45.8) |

| Physician | 19 (12.3) |

| Physiotherapist | 5 (3.2) |

| Occupational therapist | 2 (1.3) |

| Social worker | 1 (0.6) |

| Psychologist | 2 (1.3) |

| Other, for example, public health scientists, psychotherapist and quality manager | 51 (32.9) |

| Missing data | 4 (2.6) |

Following standard procedures, the first step in assessing the measurement model focused on examining the loadings to assess the reliability of all measured items. The measured items, displayed in table 1, are assessed to ensure that they apply correctly to their latent variable, that is, capture experiences, identify and prioritise, taking action or evaluate. The recommended threshold value of 0.70729 was applied and all measured items had loadings that exceeded this threshold; hence, good reliability was confirmed.

Moreover, the results revealed that the discriminant validity of the model was sufficient, meaning that the latent variables (in this study phase of improvement cycle) have stronger relationship to its own measured items (see table 1) than to measured items related to another latent variable. The discriminant validity was evaluated by the AVE method, stating that the off-diagonal values should all be lower than the diagonal values.29 Following this method, the model’s latent constructs have good discriminant validity (see table 3).

Table 3.

Assessment of validity of the model (average variance extracted)

| Capture experiences | Evaluate | Identify and prioritise | Radicality | Taking action | |

| Capture experiences | 0.912 | ||||

| Evaluate | 0.557 | 1.000 | |||

| Identify and prioritise | 0.603 | 0.547 | 0.886 | ||

| Radicality | 0.457 | 0.402 | 0.402 | 1.000 | |

| Taking action | 0.658 | 0.619 | 0.706 | 0.464 | 0.877 |

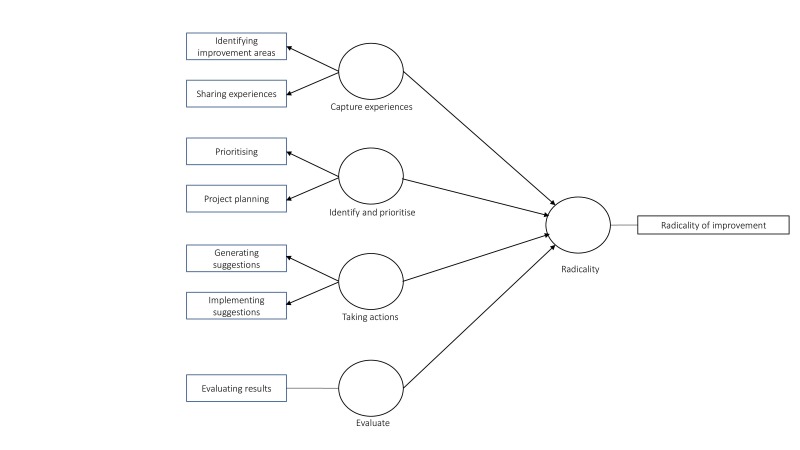

The model was estimated using PLS, figure 1 displays the model and its four paths. From left to right, each path consists of the measured items and the associated latent variable, all modelled to assess the potential impact on the radicality of the solution resulting from the QI project.

Figure 1.

Model of radicality of improvement. Latent variables are the phases of an improvement project: capture experiences, identify and prioritise, taking action and evaluate.

Starting from top to bottom, the path coefficients were 0.220, 0.063, 0.200 and 0.121 for capture experiences, identify and prioritise, taking action and evaluate, respectively. The coefficients reflect the magnitude of the potential impact on radicality, in other words the extent to which involvement in respective phase can lead to improvements that address previously unmet patient needs. This meant that the phases with most impact on radicality appeared to be capture experiences and taking action, while least impact was to be found in the phase of identify and prioritise.

Focusing the phases with most impact and looking at the underlying measured items, patient involvement in the capture experience phase means to include patients in the process of understanding (not only reporting on) patients’ experiences and based on this involve patients in identification of improvement areas. In later parts of the improvement cycle, most impact is related to patient involvement in the phase taking action, meaning generating and implementing improvement suggestions.

Discussion

The present study showed that the involvement of patients in QI might be a key to identifying and realising more radical solutions. However, the impact of patient involvement on radicality varied depending on the point at which patients were involved in a QI project. The impact of patient involvement on radicality appears to be highest in the phases of capture experiences and taking action. In contrast, patient involvement had the lowest impact on radicality in the identify and prioritise phase. These results are in accordance with previous studies in other disciplines that have systematically investigated the role of customer participation in development projects.36 The finding should not be interpreted as a non-existing need to involve patient in those two latter phases. The results point to a relatively higher influence of patient involvement in the phases of capture experiences and taking action when focusing on radicality.

The shift towards an outside-in perspective might explain why patient involvement influences radicality. Traditionally, QI has been carried out by staff within organisations. However, a central problem with this approach is that staff’s insight into various solutions may be constrained by their own experience.37 Furthermore, healthcare staff are trained in evidence-based medicine, where changes are more often incremental per se, and one first learns something and then applies it. It is therefore unlikely that a QI team with only healthcare staff will generate and implement ideas that conflict with their own assumptions. However, if QI teams interact with patients in the phases of capturing experiences and taking action, a new understanding of needs, anchored in patients’ experiences rather than current healthcare practices, might be identified. This can lead to a sense of urgency and a tension for change.8 In such QI projects, patients’ views would balance the inside-out perspective of staff.

However, as previously argued, patient involvement presents several challenges, such as the need for resources12 and problems related to tokenism,13 14 validity15 and competence.16 First, dividing an improvement cycle into distinct phases and identifying the stages in which patient involvement has the greatest impact on the radicality of the improvement will enable the allocation of resources required for patient involvement to the most relevant phases. Second, minimising the risk of tokenism requires conditions for authentic patient involvement that can lead to a sense of urgency and a tension for change. This can best be provided in the capturing experiences and taking action phases, where this study shows that patient involvement has most impact on radicality. Thus, patient involvement in these phases can help to reduce the risk of tokenism, that is, ensuring that the patients’ voice is listened to and acted on. Our study, therefore, supports the notion that patients’ active participation in practical QI projects lays a foundation for real impact. Third, in contrast with previous studies suggesting validity problems when involving patients,15 this study measured healthcare professionals’ perception of patients’ influence and experience, and showed that patient involvement increases the likelihood of finding a radical solution particularly in certain phases of a QI project. Fourth, concerns have been raised as to the competence of patients to contribute to QI. This can be due both to a lack of professional knowledge12 and to the sharing of power, which challenges current power relations.13 17 According to Gaventa and Cornwall,38 the relationship between power and knowledge can be regarded from at least three perspectives: (1) knowledge owned by powerful experts and transferred to the powerless as truth yielded by objective research; (2) knowledge as controlled by the powerful, where the powerless may be occasionally invited to produce and act on a set agenda of knowledge creation and (3) an emphasis on participation in the knowledge production, where coproduction builds greater awareness and self-consciousness of capacities for action.38 According to this, only in the third perspective can healthcare staff perceive patient’s perspectives as equally important, and knowledge about what needs to be improved as cocreated without a set agenda. Having such an approach means that the patient is regarded as a capable person with unique knowledge39 and a partner in developing care through participation in QI. The findings in our study support this view while still respecting the professional knowledge held by healthcare staff (ie, given that the identify and prioritise phase had the lowest impact on radicality, it should be developed by professionals based on their broader healthcare experience).

As it is based on data from a variety of QI projects cross different specialties of care, the findings from this study have practical implications for improvement projects that involve patients. Generally, as healthcare is cocreated and produced within the interactions between patients and health professionals,12 the staff’s perspective should be balanced with that of patients. Power and ethics could be a barrier to forging a true partnership between patients and staff, but our results can nevertheless help by defining when patient involvement is most beneficial for radicality. Besides proving the criticality and usefulness of patient involvement, this knowledge can help prioritise resources spent on patient involvement. Hence, current change models (eg, Nolan’s model for QI, Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA)) and more specific patient involvement frameworks (eg, experienced-based codesign, tracer methodology) may benefit from infusing the findings from the present study in their work. Further, the findings can be used in order to identify specific methods, for example, process mapping and fishbone analyses, where incorporation of the patient might be efficient.

In further research, a general question to be asked in relation to these frameworks and methods is if patients are invited to participate in various phases and activities and if they are effectively engaged. The findings can also be used as basis for understanding the relative importance of various patient activities in cocreation models where patients are involved as representatives in trial management groups, steering committees and data monitoring teams.40 Furthermore, it would be of interest for future research to study how the impact of patient involvement on radicality is affected by the type of healthcare setting, such as acute versus chronic care, standardised simple procedures versus complex care, as well as type of specialty. Another potential area for future research would be to identify what methods could be used to support patient involvement in the different phases of QI. For instance, well-established methods, such as concept mapping,41 where there is a clear distinction between stakeholders’ and researchers’ responsibilities within the cycle, could be tested in patient involvement in healthcare.

This study has several limitations. First, it clarifies the effects of patient involvement in QI initiatives in the specific context of Swedish healthcare. Second, as patient involvement in QI is a relatively new practice, the sampling strategy involved choosing participants who were trained and had experience in QI.25 26 When these practices have been in use for a longer time and by more healthcare professionals, a different sampling strategy might be used and also include patients with experience from QI work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, before considering involving patients in improvement initiatives, it is essential to decide how and when to involve them. Consideration should be given to the phase in which patients have the potential to cocreate radical and valuable insights for improvement initiatives. This study showed that patient involvement has the greatest impact on radicality in the phases capture experiences and taking action, a moderate impact in the evaluate phase and the lowest impact on the identify and prioritise phase.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: IG, ME and SG developed and directed the survey. IG and ME performed the statistical analysis. IG, ME and FS designed this specific study and did the draft and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg granted exemption from a formal ethical approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The database is held at the host institution and analysis and access to the data are limited to on-site access. More detailed analysis results are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Mohrman S, Shani AB, McCracken A. Organizing for sustainable healthcare. The emerging global challenge : Mohrman S, Shani AB, Organizing for sustainability (Vol. 2). Bingley, UK: Emerald, 2012:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:626–32. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. . Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect 2014;17:637–50. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA 2008;299:1182–4. 10.1001/jama.299.10.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charmel PA, Frampton SB. Building the business case for patient-centered care. Healthc Financ Manage 2008;62:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bessant J, Maher L. Developing radical service innovations in healthcare— role of design methods. International Journal of Innovation Management 2009;13:555–68. 10.1142/S1363919609002418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taran Y, Boer H, Lindgren P. Theory building—towards an understanding of business model innovation processes: In Proceedings of the international DRUID-DIME academy winter conference, economics and management of innovation, technology and organizational change, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elg M, Engström J, Witell L, et al. . Co‐creation and learning in health‐care service development. J of Manag 2012;23:328–43. 10.1108/09564231211248435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spinuzzi C. The methodology of participatory design. Technol Commun 2005;52:163–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Armstrong N, Herbert G, Aveling EL, et al. . Optimizing patient involvement in quality improvement. Health Expect 2013;16:e36–e47. 10.1111/hex.12039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Osborne SP, Strokosch K. It takes two to tango? Understanding the Co-production of public services by integrating the services management and public administration perspectives. British Journal of Management 2013;24(S1):S31–S47. 10.1111/1467-8551.12010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. . Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eikeland O. Condescending ethics and action research: Extended review article. Action Research 2006;4:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Snape D, Kirkham J, Preston J, et al. . Exploring areas of consensus and conflict around values underpinning public involvement in health and social care research: a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004217 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E, et al. . A review of literature about involving people affected by cancer in research, policy and planning and practice. Patient Educ Couns 2007;65:21–33. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Batalden PB, Stoltz P. A framework for the continual improvement of health care; building and applying professional and improvement knowledge to test changes in daily work. Joint Comm J Qual Improv 1993;19:432–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith F, Wallengren C, Öhlén J. Participatory design in education materials in a health care context. Action Research 2017;15:310–36. 10.1177/1476750316646832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iedema R, Merrick E, Piper D, et al. . Codesigning as a discursive practice in emergency health services: the architecture of deliberation. J Appl Behav Sci 2010;46:73–91. 10.1177/0021886309357544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gustavsson SM. Improvements in neonatal care; using experience-based co-design. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2014;27:427–38. 10.1108/IJHCQA-02-2013-0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, et al. . The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:28–38. 10.1093/intqhc/mzr066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wiig S, Storm M, Aase K, et al. . Investigating the use of patient involvement and patient experience in quality improvement in Norway: rhetoric or reality? BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:206 10.1186/1472-6963-13-206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bate P, Robert G. Toward more user-centric OD: Lessons from the field of experience-based design and a case study. J Appl Behav Sci 2007;43:41–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elg M, Witell L, Poksinska B, et al. . Solicited diaries as a means of involving patients in development of healthcare services. Int J Qual Serv Sci 2011;3:128–45. 10.1108/17566691111146050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Codex. Regler och riktlinjer för forskning. http://www.codex.uu.se/ (accessed 1 Mar 2015).

- 25. Pettigrew AM. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organization Science 1990;1:267–92. 10.1287/orsc.1.3.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van de Ven A. Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press on Demand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andersson AC, Elg M, Perseius KI, et al. . Evaluating a questionnaire to measure improvement initiatives in Swedish healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:48 10.1186/1472-6963-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donetto S, Tsianakas V, Robert G, et al. . (EBCD) to improve the quality of healthcare: mapping where we are now and establishing future directions. London: King’s College London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gustafsson A, Kristensson P, Witell L. Customer co‐creation in service innovation: a matter of communication? J Serv Manag 2012;23:311–27. 10.1108/09564231211248426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooper RG. The dimensions of industrial new product success and failure. Journal of Marketing 1979;43:93–103. 10.2307/1250151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tidd J, Bessant J. Managing Innovation. Integrating Technological, Market and Organisational Change. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hertog PD, Gallouj F, Segers J. Measuring innovation in a ‘low-tech’ service industry: the case of the Dutch hospitality industry. The Service Industries Journal 2011;31:1429–49. 10.1080/02642060903576084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cocosila M, Archer N. Perceptions of chronically ill and healthy consumers about electronic personal health records: a comparative empirical investigation. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005304 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors. J Marketing Res 1981;18:39–50. 10.2307/3151312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fornell C, Cha J. Partial Least Squares: Bagozzi RP, Advanced methods of marketing research. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1994:52–78. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chang W, Taylor SA. The effectiveness of customer participation in new product development: A Meta-Analysis. J Mark 2016;80:47–64. 10.1509/jm.14.0057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. von Hippel E. Lead users: A source of novel product concepts. Management Science 1986;32:791–805. 10.1287/mnsc.32.7.791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gaventa J. Cornwall A. Power and Knowledge In: Reason P, Bradbury H, eds The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. Cornwall, UK: Sage Publications, 2008:172–89. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, et al. . Person-centered care-ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2011;10:248–51. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. South A, Hanley B, Gafos M, et al. . Models and impact of patient and public involvement in studies carried out by the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit at University College London: findings from ten case studies. Trials 2016;17:376 10.1186/s13063-016-1488-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, et al. . An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1392–410. 10.1177/1049732305278876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.