Abstract

Introduction

Despite favourable results from structured face-to-face treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) in Sweden through the Better management of patients with OsteoArthritis (BOA) initiative, only around 20% of people with knee or hip OA receive the primary treatment recommended by international guidelines (ie, information, exercise, weight management). In 2014, a digital treatment programme named Joint Academy was introduced in Sweden, based on the same concept as the face-to-face BOA programme. In line with BOA, Joint Academy follows national and international guidelines and best practice for OA treatment. Results from observational studies suggest that this digital treatment is a valuable alternative to the traditional treatment approach and can positively impact patients’ function and pain. However, conclusions from such studies commonly suggest that more rigorous testing is necessary to ascertain the benefits of digital treatment delivery for people with OA.

Methods and analysis

A randomised clinical trial will be performed, comparing regular face-to-face care according to BOA with the digital version, Joint Academy. A total of 270 participants with clinically diagnosed knee OA will be recruited at primary care centres and randomised to either standard treatment (BOA) for 3 months, or the experimental group (digital intervention programme). Both groups will receive educational sessions and exercises yet with a difference in programme deliverance. The objective of the trial is to evaluate the effectiveness of the online treatment programme, in comparison with BOA. The two treatment groups will be compared with respect to the number of repetitions of the 30 s chair stand test at 3, 6 and 12 months, using a mixed model repeated measures analysis of variance.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been attained from the Regional Board of Ethics in Lund, Sweden (Dnr 2017/719). Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Keywords: adult orthopaedics, knee, telemedicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will help in clarifying the potential effect and cost-effectiveness of an online osteoarthritis treatment, facilitating implementation decisions for healthcare providers.

The sample size ensures sufficient power for group comparisons.

The trial has a pragmatic design to compare two existing treatment programmes without any alterations to fit trial methodology.

The nature of the two treatment modalities makes blinding difficult, although patients are blinded regarding what treatment is hypothesised to be superior.

Introduction

To facilitate the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for osteoarthritis (OA) treatment,1–4 the Swedish National quality register BOA (Better management of patients with OsteoArthritis) was established, with an OA self-management programme including education and supervised exercise (the BOA programme). The purpose of the BOA programme is to provide patients with structured and relevant OA information and the opportunity to perform joint-strengthening exercises. The BOA programme is clinic based and provided at about 500 primary care centres.3 The programme varies slightly between regions, but in general it consists of three educational sessions and for most patients 6 weeks of individually adapted neuromuscular exercises. The programme has been shown to be feasible in clinical practice; the intervention was rated as good or very good by 94% of the patients. After 3 months, 62% reported daily use of what they had learnt and 91% reported weekly use.5 Preliminary results also suggest significant improvements in pain, quality of life and self-efficacy for participants of the BOA programme, in comparison to patients on a waiting list for surgery.6 However, despite the systematic and thorough work put into BOA and the BOA programme, only around 20% of the Swedish OA population seeking primary care for OA enter the self-management programme.7

In 2014, Joint Academy (JA), a digital platform for individuals with clinically verified OA,8 was created based on the face-to-face BOA programme. In an observational pilot study, 53 patients with OA were enrolled into JA and results showed that the mean pain level continuously decreased during the 30-week study period. In addition, the patients highly recommended JA to other patients with OA.7 In a recent publication, these results were confirmed in a study cohort of 350 patients.9 Although inferences of causality cannot be made due to the lack of a control group, these results suggest that JA has the potential to successfully deliver treatment to patients with OA. Digital treatment may be a cost-effective alternative to face-to-face meetings with clinicians when delivering treatment that promotes changes in lifestyle, since follow-up and guidance for the patient are easily accessible through computers/laptops or wearable devices. In addition, traditional healthcare cannot be required to offer necessary chronic treatment to chronic diseases but must rely on patients’ self-management. Digital support may prove valuable in this regard. Currently there is evidence of the effectiveness and/or efficacy of digital interventions for increasing physical activity, reducing the risk of diabetes and weight loss, or alleviating chronic joint pain.10–12 However, previous research within the area of chronic joint pain has concluded that studies with more rigorous design are needed, especially for enabling comparison to standard care.13 Hence, it is still unknown whether a digital programme may benefit people with OA, and if so, to what extent compared with current standard treatment. The objective of the trial is to evaluate the effectiveness of the digital treatment programme in comparison with BOA, primarily with reference to increased physical function, for individuals with knee OA. Thus, the proposed randomised clinical trial will provide new knowledge regarding whether an individualised round-the-clock treatment delivered digitally is superior and more cost-effective than regular OA care.

Methods and analysis

In this two-armed randomised controlled superiority trial (RCT), 270 patients with knee OA will be recruited, 135 allocated to each arm. Superiority is chosen over non-inferiority due to the lack of RCT’s showing effects of the BOA programme on pain and function, in comparison to a control group. The primary evaluation of outcomes (see Outcome measures for details) will be performed at 12 months. Ten primary care centres around Sweden that are experienced in OA and use the face-to-face BOA programme will participate and include a minimum of 26 patients each (13 patients per group). After providing consent to participate in the study, all participants will be registered in the study database. All outcome variables will be patient reported at baseline, and at 3, 6 and 12 months after start, for both groups.

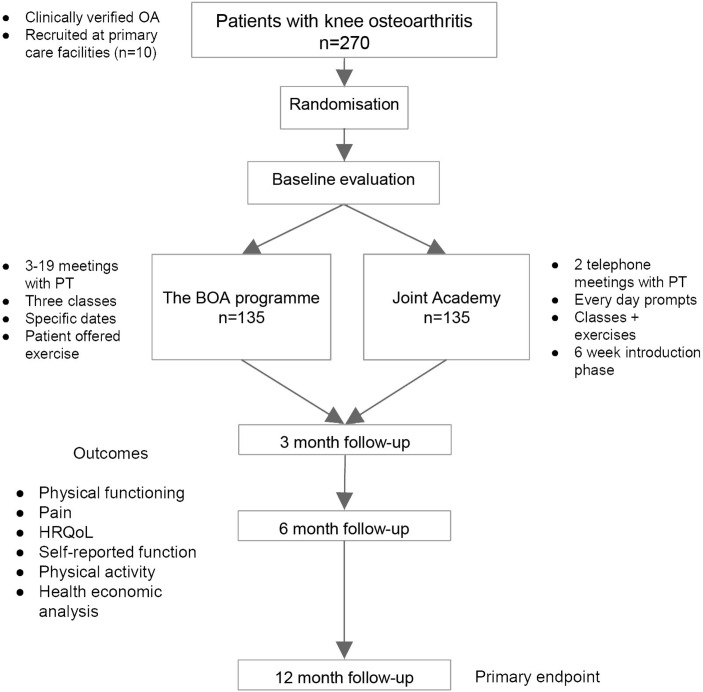

The allocation of patients will be performed using permuted blocks with a random block size (4 and 6) and stratification for gender and centre. The randomisation sequences will be based on computer-generated random numbers, and concealed treatment allocation will be achieved using sequentially numbered opaque envelopes that are only opened once the patient’s consent to participate has been received. A statistician will generate the random numbers and instructions of use, while the physiotherapist at each clinic will be responsible for preparation and distribution of envelopes. The treatment allocation will be concealed from the statistician performing the data analysis, but unfortunately the design of the study and the nature of the two treatment modalities prevent blinding of patients and physiotherapists. Participants randomised to JA will receive a link to the application by email, after which these participants can start the programme. Participants randomised to the BOA programme will be invited to their primary care centre to participate, according to regional standard protocol. Figure 1 contains a flow chart of the overall study design.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design. BOA, Better management of patients with OsteoArthritis; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; OA, osteoarthritis; PT, physiotherapist.

Patient selection: population and sample

For patient recruitment, primary care centres around Sweden that are experienced in OA and currently offering the face-to-face BOA treatment to 70–100 patients per year will be enrolled and recruit patients. All patients being referred to the clinic or seeking care for OA, visiting the care centre for a physiotherapist evaluation and being eligible (fulfilling the inclusion criteria) will be invited to participate in the study to minimise selection bias. Anonymous data on the number of patients declining participation along with stated reasons for declining will be collected at each clinic.

A prerandomisation screening will be performed in which patients will be asked to report their knee pain (numeric rating scale (NRS) 0–10) as well as perform a 30 s chair stand test (30 CST) to minimise the risk of floor and ceiling effects. All inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed below.

Inclusion criteria

A clinical diagnosis of knee OA according to the American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria as well as national and international guidelines14 15: knee pain and three of the following: >50 years of age, morning stiffness >30 min, crepitus, bony tenderness, bony enlargement, no palpable warmth.

Reported knee pain ≥4 and ≤8 on the NRS,16 and ≥6 to ≤16 in number of repetitions during a 30 CST,9 at prerandomisation screening.

Able to handle a software program via phone, tablet or computer.

Able to read and write the Swedish language.

Exclusion criteria

Neurological disease, inflammatory joint disease or cancer.

Cognitive disorder, for example, dementia.

Exercise is contraindicated for the patient.

Estimated sample size and power

The two treatment groups have been compared with respect to the number of repetitions during the 30 CST (see Outcome measures). The null hypothesis was that there is no difference in the mean number of repetitions between the experimental treatment (JA) and the standard treatment (the BOA programme). The alternative hypothesis was that the treatment effects differ. For sample size calculation, the null hypothesis has been tested with a one-sided significance level of 0.025, equivalent to a two-sided significance level of 0.05, using Student’s t-test, assuming that the number of repetitions has a Gaussian distribution.

The sample size was calculated for a number of different scenarios with treatment effects of 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 repetitions, statistical power of 0.80 and SDs of 4.0–5.0 repetitions using Stata V.15. Calculations are based on the previously reported mean number of repetitions and SD in a Swedish sample, as well as the major clinically important improvement (MCII) in persons with OA.9 17 Hence, according to table 1, a total of 162 patients are required to be 80% sure that the experimental treatment is superior to the standard treatment, if the SD of 30 CST repetitions is 4.5 and the MCII is 2.0. To compensate for 40% withdrawals, in line with withdrawals reported in the BOA programme,3 the number of randomised patients has been adjusted to 270. A sample size reassessment will be performed after 6 months of recruitment in order to verify the assumptions made or to adjust the sample size if the assumptions are not fulfilled. This sample size reassessment will be blinded. No interim analysis will be performed.

Table 1.

Sample size calculation based on difference between treatments and SD of 30 CST repetitions, with 80% statistical power and 5% statistical significance

| Difference | SD | ||

| 4.0 | 4.5 | 5.0 | |

| 1.0 | 506 | 638 | 788 |

| 2.0 | 128 | 162 | 200 |

| 3.0 | 58 | 74 | 90 |

Calculated using Student’s t-test.

30 CST, 30 s chair stand test.

Outcome measures

Table 2 provides an overview of measurements according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

Table 2.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) schedule

| Study period | |||||

| Enrolment | Allocation | Postallocation | |||

| Time point | -t1 | 0 Baseline | t1 3 months | t2 6 months | t3 12 months |

| Enrolment | |||||

| Eligibility screen | X | ||||

| Individual informed consent | X | ||||

| Allocation | X | ||||

| Interventions | |||||

| (Standard treatment) | X | X | |||

| (Experimental treatment) | X | X | |||

| Assessments | |||||

| Demographics | X | X | X | X | |

| Physical functioning* | X | X | X | X | |

| Knee pain† | X | X | X | X | |

| HRQoL‡ | X | X | X | X | |

| Self-reported function§ | X | X | X | X | |

| Physical activity¶ | X | X | X | X | |

| PASS | X | X | X | ||

| Absenteeism** | X | ||||

| Presenteeism†† | X | X | X | X | |

| Healthcare costs‡‡ | X | ||||

*30 s chair stand test.

†Numeric rating scale (NRS) 0–10.

‡HRQoL, health-related quality of life measured using the EQ-5D-5L.

§KOOS-PS (Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score–Physical Function Shortform).

¶The Swedish Board of Health and Welfare indicator questions.

**Productivity loss measured using data from the Social Insurance Agency’s Register.

††Productivity loss while working, measured using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI).

‡‡Estimated using data from the Swedish patient register, medication register and data from each participant’s primary care provider.

PASS, patient acceptable symptom state.

The primary outcome is the change in number of repetitions of the 30 CST (continuous variable) from baseline to 12 months’ follow-up.18 In the 30 CST, the participant rises from a chair repeatedly for 30 s. Instructions will be given to both groups using an instructional video, and the number of repetitions will be recorded by the participant.

Secondary outcomes

Knee pain will be measured using the NRS, a valid, reliable and appropriate scale for pain intensity measurement.19 The NRS is an 11-point Likert scale (0–10) (continuous variable) and the participants will be asked to indicate the average pain in the specified knee over the last week. Higher scores indicate more severe pain.20 Health-related quality of life will be measured using a descriptive EQ-5D-5L instrument.21 The EQ-5D-5L instrument contains five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems. The patient will be asked to indicate his/her health state in each dimension. In addition, an index score based on the five dimensions and general population value surveys is calculated using an EQ-5D index calculator. The EQ-5D index calculator combines the individual levels from the five dimensions into one of 3125 health states, and converts the state into a single index value using a country-specific value set.

Self-reported function (continuous variable) will be measured using Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score–Physical Function Shortform.22 The instrument contains seven items covering daily activities: rising from bed, putting on socks, rising from sitting, bending to the floor, twisting/pivoting on the painful knee, kneeling and squatting. A total score will be calculated and converted using a nomogram of a 0–100 score.

Physical activity/exercise (continuous variable) will be measured using the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare indicator questions.23 The instrument contains two questions: patient-defined minutes of physical activity and minutes of exercise, both per week. The amount of activity minutes/week is calculated by adding up the number of minutes (number of minutes of exercise is multiplied by 2 before summing up).

To assess the patient acceptable symptom state, two questions previously described by Ingelsrud et al 24 will be used; participants will be asked to report whether current symptoms are acceptable, and if not, if they feel the treatment has failed.

Quality-adjusted life-years will be calculated by multiplying a health state utility (measured by the EQ-5D-5L index score) by the time spent in that health state.25 This measurement will be used in conducting a cost-utility analysis alongside the trial.

Productivity loss refers to monetary value of the time lost due to the disease or its treatment. It includes two main parts: absenteeism (time missed from work) and presenteeism (decreased productivity while working). In the current study, absenteeism ≥14 days will be measured using data from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency’s Register. To measure absenteeism of less than 14 days and presenteeism, a validated questionnaire entitled ‘the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI)’26 will be used. Productivity losses will be translated into monetary values using the human capital approach based on the average salary in Sweden. Subsequently, to estimate healthcare cost per patient related to their OA, data from the inpatient register, medication registry and each patient’s primary healthcare provider will be accessed. Data on the number and type of visits, prescribed medication and type of healthcare provider will be used for analysis.

In terms of the secondary outcomes, mean knee pain will be tested confirmatory only if the primary outcome is statistically significant. The other secondary outcomes are considered supportive, explanatory or exploratory. Multiplicity issues will therefore not complicate the evaluation.

For a brief structured summary of the trial according to the WHO Trial Registration data set, see online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2018-022925supp001.pdf (162.2KB, pdf)

Questionnaires

For measurements in the BOA programme, questionnaires are distributed at baseline, 3 months (3-month evaluation includes an individual physiotherapy visit at the clinic) and at 6 and 12 months. At 6 and 12 months, questionnaires are delivered by mail. Participants entering the JA programme will complete online questionnaires (containing the measurements described previously) at baseline, after 6 weeks (according to standard protocol in JA) and at 3, 6 and 12 months. Additionally, JA participants will be asked to report their knee pain using an NRS scale weekly during the study period.

Standard treatment: the BOA programme

Individuals randomised to the BOA programme will be offered three educational sessions at their respective clinic, according to the standardised minimal intervention in BOA. The first session consists of providing information regarding the nature of OA, evidence-based risk factors, general symptoms and available treatment. The second session focuses on the benefits and mechanisms behind the effects of exercise, daily life activities, how to cope with OA and practical information on how to self-manage the disease. In the final session, an OA-communicator, an individual with OA, presents their experience with living with the disease, and how to manage on a more personal level. Each session is 2 hours long and is carried out during daytime/office hours. After attending the sessions, the participant will meet with a physiotherapist and discuss whether he or she wants an individually adapted exercise plan, or no exercise. If the exercise plan is chosen, the individual is offered to join physiotherapist-supervised group exercises performed 12 times (twice per week for 6 weeks) during daytime, or receive an instruction leaflet for home exercises (unpublished data from BOA suggest that 12.5% choose not to participate in supervised exercise).

Although all centres offering the BOA programme in Sweden follow the original concept outlined by BOA,3 there may be regional differences between centres in terms of the total amount of exercise sessions, and whether they are offered before or after the three theoretical sessions.

In total (including start-up visits, screening, education and training as well as end sessions), the number of personal visits for each patient will range from 6 to 22 (regional variation taken into account).

After the programme, patients receive a leaflet describing their exercises, and are advised to continue exercising at home, according to the routine at the centre they attended.

The physiotherapist will promote participant retention continuously through the programme by discussing the importance of continued study participation with patients. Patient adherence is continuously documented by the physiotherapist in their medical record, and after 3 months adherence is reported. No concomitant care is prohibited during trial participation.

Experimental treatment: JA

Individuals in the JA group will undergo an interactive 6-week introduction covering how to treat their OA pain, followed by a continuous programme to enable continued exercising and maintained individual adherence with the necessary lifestyle changes. The 6-week introduction includes individualised physical activity, education about lifestyle changes and one-on-one asynchronous coaching from a physical therapist via online chat (ie, without the participant having to visit a specific location). The introduction and the continuous programme together run for a total of 1 year.

In the introduction neuromuscular exercises are introduced to improve lower extremity physical function and strength. The participant is instructed to perform two of these exercises every day of the week and each exercise has 1–5 levels of intensity. The level of intensity is based on an algorithm that adjusts for individual progress and the patient’s perceived ability to perform the exercise without exacerbating pain. Thus, JA individualises a schedule for each participant.

Furthermore, participants watch short and engaging video sessions or read text material explaining how to live with OA. These are based on the educational material within the BOA programme (developed by trained health professionals) and provide education regarding lifestyle changes. After each session, participants are given a quiz to confirm that the take-home message has been received. The educational component of JA is developed to improve the patient’s understanding of the disease and the importance of being physically active. Simultaneously, participants are assigned a professional physiotherapist who guides each patient via the interactive interface within the platform. All physiotherapists are extensively educated in the platform and have considerable experience in treating people with OA. In the continuous programme, exercises will be delivered a patient-specified number of times per week. Similar to the introduction phase, a physiotherapist is constantly available via the chat function. Push notifications will be delivered every day of scheduled exercise, reminding participants to enter JA, exercise and report their experience of each activity. As in the first part of the programme, difficulty level of exercises can be altered by either patient or physiotherapist. New educational sessions on subjects related to OA as well as previous ones will be steadily available. Should technical issues arise, the participant has constant access to the regular support channel offered at JA.

As described previously, the physiotherapist promotes participant retention continuously through the programme by discussing the importance of continued study participation with patients. Adding on, for patients treated online each physiotherapist is able to continuously follow and record the patient’s adherence to the programme in the JA Physiotherapist Dashboard. No concomitant care is prohibited during trial participation.

Patient and public involvement

The BOA programme was developed on a foundation of current research and conclusions drawn from focus groups consisting of patients and representatives of the Swedish Rheumatism Association. The digital version (JA) is, as previously described, based on the same concept. Furthermore, beta-versions of the digital platform have been improved by analysing questionnaires and opinions from patients recruited via the Swedish Rheumatism Association. These patients were able to test JA and were interviewed in depth about their opinions. In addition, the outcomes in the proposed study are in agreement with the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement Standard set for knee and hip OA, defined through close involvement of patients. There was no patient involvement in regard to other aspects of the study design. Results will be disseminated to those participants expressing their interest during, before or after the study.

Statistical analysis plan

The statistical analysis will be performed in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonisation’s Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines and the report will be developed in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement. P values and 95% CIs for the change in number of 30 CST repetitions from baseline to 12 months between the two treatment groups will be calculated using a mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis of variance. In this statistical model, patient will be included as a random factor and follow-up time and treatment group as fixed factors. Treatment–time interactions and covariates for the endpoint’s baseline imbalance and randomisation stratification factors (gender and centre) will also be included. An unstructured variance-covariance matrix will be considered first. If this cannot be estimated, compound symmetry will be assumed instead.

As the MMRM can handle imbalanced data, there will be no imputation of missing data. Both the intention-to-treat and the per-protocol population will be analysed, but the intention-to-treat analysis will be considered the main analysis.

A p value will be presented, and if this is small enough (ie, <0.05) to convincingly reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the intention-to-treat population for the primary outcome, the trial will be considered to show superiority for the treatment with the superior outcome. Additional exploratory and hypothesis-generating analyses will be performed to identify gender differences in the treatment effect, and these analyses will be performed both by stratifying by gender and by including terms for estimating interaction effects with gender. After collecting the required data, a cost-utility analysis from a societal perspective will be conducted. The uncertainty in cost-utility analysis will be handled using a bootstrap approach. All statistical calculations will be performed using Stata V.15 (StataCorp. 2017. College Station, TX: StataCorp).

Ethics and dissemination

The trial will be performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the Regional Board of Ethics (RBE), Lund University, Sweden (Dnr 2017/719). Important protocol modifications will be communicated to the RBE and participating clinics.

Potential participants must provide written informed consent to their physiotherapist before entering the study. All participant data at each clinic will be handled as patient-related data and therefore securely stored and administered according to Swedish Law. The JA database is equipped with modern authorisation control as well as being fully encrypted. All patient-related data are deidentified (anonymous) and handled according to the standard of the Secure Sockets Layer certificate. Two-factor authorisation is used for user logins. Further, JA is in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), as well as being a Swedish Health and Social Care Inspectorate (IVO)-approved healthcare provider. Only data of relevance to the study and its analyses (final trial data set) will be shared with the principal investigator (HN), the lead statistician (JR) and the health economics analyst (AAK). All participants are insured, through the Swedish Patient Injury Act or the specific healthcare provider. The results of the main trial and each of the secondary outcomes will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals and will also be disseminated to participants expressing interest. Statistical analysis plan and informed consent form will be made available 6 months after study completion. Clinical study report and analytical code will be available after publication of results, on reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HN, JR, AAK and LED designed the study. HN wrote the first draft of the manuscript and together with JR, AAK and LED revised the manuscript and produced the final draft. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. For this protocol and the final trial report, no ghost authors, guest authors or professional medical writers have or will be used and author eligibility is and will be based upon the ICMJE Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly work in Medical Journals.

Funding: This work has been supported by the Swedish Rheumatism Association (R-753221), Stiftelsen för bistånd åt rörelsehindrade i Skåne and Vinnova (2016-04187). Non-financial support in the form of assistance in reaching potential participating healthcare units has been received from the BOA register, while non-financial support from Arthro Therapeutics comes in the form of technical assistance in matters regarding the digital platform.

Disclaimer: The study sponsors and funders have had no role in study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication, and do not own ultimate authority over any of these activities.

Competing interests: HN is hired as a part-time consultant for Arthro, the corporation behind JA, and LED is the unemployed CMO of Arthro.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Regional Board of Ethics, Lund University, Sweden (Dnr 2017/719).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Evidence-based guideline. 2nd edition, 2013. http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/TreatmentofOsteoarthritisoftheKneeGuideline.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence - Osteoarthritis: care and management. Clinical guideline. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177

- 3. Better management of patients with OsteoArthritis (BOA). https://boa.registercentrum.se/boa-in-english/better-management-of-patients-with-osteoarthritis-boa/p/By_o8GxVg

- 4. Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:476–99. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thorstensson CA, Garellick G, Rystedt H, et al. Better Management of Patients with Osteoarthritis: Development and Nationwide Implementation of an Evidence-Based Supported Osteoarthritis Self-Management Programme. Musculoskeletal Care 2015;13:67–75. 10.1002/msc.1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jönsson T, Ekvall Hansson E, Thorstensson C, et al. The effect of education and supervised exercise on physical activity, pain, quality of life and self-efficacy - an intervention study with a reference group. Submitted to BMC Musculoskeletal in December 2017, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dahlberg LE, Grahn D, Dahlberg JE, et al. A Web-Based Platform for Patients With Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee: A Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc 2016;5:e115 10.2196/resprot.5665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Joint Academy. https://www.jointacademy.com/se/en/

- 9. Nero H, Dahlberg J, Dahlberg LE. A 6-week web-based osteoarthritis treatment program: Observational quasi-experimental study. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e422 10.2196/jmir.9255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bossen D, Veenhof C, Van Beek KE, et al. Effectiveness of a web-based physical activity intervention in patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e257 10.2196/jmir.2662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garg S, Garg D, Turin TC, et al. Web-Based Interventions for Chronic Back Pain: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e139 10.2196/jmir.4932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lynch SM, Stricker CT, Brown JC, et al. Evaluation of a web-based weight loss intervention in overweight cancer survivors aged 50 years and younger. Obes Sci Pract 2017;3:83–94. 10.1002/osp4.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smittenaar P, Erhart-Hledik JC, Kinsella R, et al. Translating comprehensive conservative care for chronic knee pain into a digital care pathway: 12-week and 6-month outcomes for the hinge health program. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2017;4:e4 10.2196/rehab.7258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and therapeutic criteria committee of the american rheumatism association. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1039–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. ACR Diagnostic guidelines. https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/physician-corner/education/arthritis-education-diagnostic-guidelines/#class_knee

- 16. European Medicines Agency - Clinical investigation of medicinal products used in the treatment of osteoarthritis. 2010. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_001135.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580034cf4.

- 17. Wright AA, Cook CE, Baxter GD, et al. A comparison of 3 methodological approaches to defining major clinically important improvement of 4 performance measures in patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011;41:319–27. 10.2519/jospt.2011.3515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - the 30 second chair stand test. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/30_second_chair_stand_test-a.pdf

- 19. Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:798–804. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rolfson O, Wissig S, van Maasakkers L, et al. Defining an International Standard Set of Outcome Measures for Patients With Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis: Consensus of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis Working Group. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1631–9. 10.1002/acr.22868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perruccio AV, Stefan Lohmander L, Canizares M, et al. The development of a short measure of physical function for knee OA KOOS-Physical Function Shortform (KOOS-PS) – an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:542–50. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Olsson SJ, Ekblom Ö, Andersson E, et al. Categorical answer modes provide superior validity to open answers when asking for level of physical activity: A cross-sectional study. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:70–6. 10.1177/1403494815602830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ingelsrud LH, Granan LP, Terwee CB, et al. Proportion of patients reporting acceptable symptoms or treatment failure and their associated KOOS values at 6 to 24 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A study from the norwegian knee ligament registry. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:1902–7. 10.1177/0363546515584041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sassi F, QALYs C, comparing Q. and DALY calculations. Health Policy Plan 2006;21:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993;4:353–65. 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022925supp001.pdf (162.2KB, pdf)