Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether coronary artery dominance is associated with the severity of coronary artery disease (CAD).

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Single-centre.

Participants

Between July 2015 and February 2017, 1654 patients who underwent coronary angiography (CAG) were recruited into this cross-sectional study.

Measurement and methods

According to coronary dominance, patients were classified into left dominance (LD), right dominance (RD) and codominance (CD) based on the CAG results. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to test the association between severity of CAD and coronary dominance.

Results

The total Gensini score was significantly higher in the RD group than in the left-CD group (42.3±33.6 vs 36.3±29.8; p=0.033). After adjusting for potential confounding factors, the results of multivariate linear regression showed that RD was associated with the severity of CAD (β=6.699, 95% CI 1.193 to 12.205, p=0.017).

Conclusions

The results suggest that right coronary dominance was associated with the severity of CAD.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, vascular medicine, coronary intervention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to investigate the association of right coronary dominance with the severity of coronary artery disease.

This cross-sectional study included 1654 patients who underwent coronary angiography during their hospital stay in Northern China.

The patients were recruited from a single centre; therefore, the study population of right dominance and codominance groups was relatively small.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the most common types of diseases around the world.1 It is recognised that obesity, blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, exercise, diet, cholesterol and depression were associated with the incidence of CAD.2 In clinical practice, the severity of coronary artery stenosis is usually evaluated by the Gensini score or the SYNergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with TAXus and cardiac surgery (SYNTAX) score.3 Several studies have shown that coronary artery dominance is associated with cardiovascular prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome.4–7 Variation of coronary dominance includes left dominance (LD), right dominance (RD) and codominance (CD) based on the vascular supply of the posterior interventricular septum (IVS).8 9 In the general population, RD is the most prevalent, found in approximately 70% of the population, while LD occurs in about 10% of cases and CD is present in 20% of cases.10 LD was found to be associated with increased long-term mortality in patients with CAD.11 12 However, little is known about the role of RD in CAD. Previous studies showed that RD, LD and CD have a prevalence of approximately 82%–89%, 5%–12% and 3%–7%, respectively, in a hospital population.4 13–15 There seems to have different distributions of coronary dominance between the general population and patients with CAD. Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate whether right coronary dominance was associated with CAD and its severity.

Methods

Study population

Between July 2015 and February 2017, 1654 in-hospital patients who underwent coronary angiography (CAG) during their hospital stay were recruited from the CAG database of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. All patients included in this study had standard clinical indications for CAG. The exclusion criteria were (1) previous coronary artery bypass graft operation or CAG, (2) those with chronic and systemic disease, and (3) incomplete CAG reports and medical records. All patients’ records were anonymised and de-identified before analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the hypothesis, design, conduct and data analysis, and we will not disseminate the results of this study to participants.

Definitions

Hypertension was defined as an office blood pressure over 140/90 mm Hg or a 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure over 135/85 mm Hg.16 Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed in patients with a fasting plasma glucose level ≥7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or 2-hour postload plasma glucose level ≥11.0 mmol/L (200 mg/dL).17 Smoking was defined as ever-smoked 100 cigarettes or currently smoking every day or some days.18

CAG results

All patients underwent CAG using a standard clinical technique through the femoral artery or radial artery approach.19 The CAG report was written and checked by interventional cardiologists. The phenotype of coronary dominance was divided based on the CAG. The posterior descending artery was originated the right coronary artery (RCA) in patients with RD. The posterior descending artery that diverged from the left circumflex (LCx) artery was defined as LD. Codominant anatomy was defined when the posterior descending artery (PDA) originated from the RCA and a large posterolateral branch that originated from the LCx branch reached near the posterior interventricular groove.10 13 The severity of CAD was evaluated using the Gensini score. In this scoring system, 0 indicates no abnormality, 1 represents stenosis of ≤25%, 2 represents stenosis of 26%–50%, 4 represents stenosis of 51%–75%, 16 represents stenosis of 76%–99%, and 32 represents complete occlusion. The score is then multiplied by different factors according to the functional significance of the coronary artery. The evaluation of each segment was performed by multiplying the scores by 5 for the left main trunk, by 2.5 for the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) branch, by 1.5 for the middle LAD, by 1 for the distal LAD, by 1 for the first diagonal branch, by 0.5 for the second diagonal branch, by 2.5 for the proximal LCx, by 1 for the distal LCx and posterior descending branch, and by 0.5 for the posterior branch, while the RCA was performed by multiplying the scores by 1 for the proximal, middle and distal RCA and the posterior descending branch, and by 0.5 for the posterior branch. The final score was calculated by adding the scores of each segment.20–22 The patients were then divided into four groups according to the total score (0–12, 13–24, 25–52 and ≥53).23

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.24.0. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The continuous variables are presented as mean±SD. Categorical variables are presented as number and percentages. Analysis of variance and the χ2 test were used to compare the variables between the subgroups of different grades of the Gensini score. Gensini score was divided into first grade (0–12.5), second grade (13–24.5), third grade (25–52.5) and fourth grade (≥53). Patients with LD or CD anatomies were placed in the left-CD group, while those with RD anatomy were included in the RD group. A multiple linear regression analysis was performed to test the association between the severity of CAD and the following variables: age, gender, smoking status, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, heart rate, family history of CAD, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and coronary dominance.

Results

Patient characteristics

The study included 1654 patients (1235 men and 419 women, mean age 59.4±10.4) who underwent CAG. Patients were divided into four groups based on the Gensini score, which were 0–12 (first grade; n=347), 13–24 (second grade; n=329), 25–52 (third grade; n=486) and ≥53 (fourth grade; n=492). Gender, SBP, DBP, heart rate, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, coronary vessel disease, history of CAD and coronary dominance were compared in the four groups. The baseline characteristics are shown in table 1 according to Gensini score.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Clinical variables | Total (n=1654) | First (n=347) | Second (n=329) | Third (n=486) | Fourth (n=492) |

| Age (years) | 59.4±10.4 | 58.5±9.9 | 59.1±10.6 | 59.3±10.6 | 60.2±10.4 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 1235 (74.7) | 225 (64.8) | 239 (72.6) | 368 (75.7) | 403 (81.9) |

| Female | 419 (25.3) | 122 (35.2) | 90 (27.4) | 118 (24.3) | 89 (18.1) |

| Baseline SBP (mm Hg) | 134.6±21.0 | 135.8±19.9 | 135.8±20.4 | 134.4±20.6 | 133.1±22.6 |

| Baseline DBP (mm Hg) | 78.3±12.3 | 79.1±12.9 | 78.5±12.0 | 77.7±11.3 | 78.3±12.8 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 75.5±13.2 | 74.3±12.1 | 75.3±14.0 | 75.4±12.6 | 76.6±14.1 |

| CAD risk factors, n (%) | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 321 (19.4) | 33 (9.5) | 65 (19.8) | 102 (21.0) | 121 (24.6) |

| Hypertension | 870 (52.6) | 174 (50.1) | 175 (53.2) | 263 (54.1) | 258 (52.4) |

| Current smoking | 841 (50.8) | 156 (45.0) | 170 (51.7) | 262 (53.9) | 253 (51.4) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 182 (11.0) | 42 (12.1) | 37 (11.2) | 51 (10.5) | 52 (10.6) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||||

| AMI | 730 (44.1) | 44 (12.7) | 97 (29.5) | 251 (51.6) | 338 (68.7) |

| Unstable angina | 311 (18.8) | 67 (19.3) | 83 (25.2) | 81 (16.7) | 80 (16.3) |

| CAD on CAG, n (%) | |||||

| One-vessel disease (≥50%) | 465 (28.1) | 239 (68.9) | 124 (37.7) | 76 (15.6) | 26 (5.3) |

| Multivessel disease (≥50%) | 1189 (71.9) | 108 (31.1) | 205 (62.3) | 410 (84.4) | 466 (94.7) |

| History, n (%) | |||||

| Prior MI | 134 (8.1) | 9 (2.6) | 16 (4.9) | 49 (10.1) | 60 (12.2) |

| Family history of CAD | 475 (28.7) | 107 (30.8) | 98 (29.8) | 126 (25.9) | 144 (29.3) |

| Coronary dominance, n (%) | |||||

| Right dominance | 1500 (90.6) | 304 (87.6) | 297 (90.3) | 445 (91.5) | 454 (92.3) |

| Left dominance | 110 (6.7) | 30 (8.7) | 22 (6.7) | 30 (6.2) | 28 (5.7) |

| Codominance | 44 (2.7) | 13 (3.7) | 10 (3.0) | 11 (2.3) | 10 (2.0) |

Four groups were based on the Gensini score: first grade (0–12.5), second grade (13–24.5), third grade (25–52.5) and fourth grade (≥53). Results are presented as mean±SD or n (%).

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; bpm, beats per minute; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAG, coronary artery angiography; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

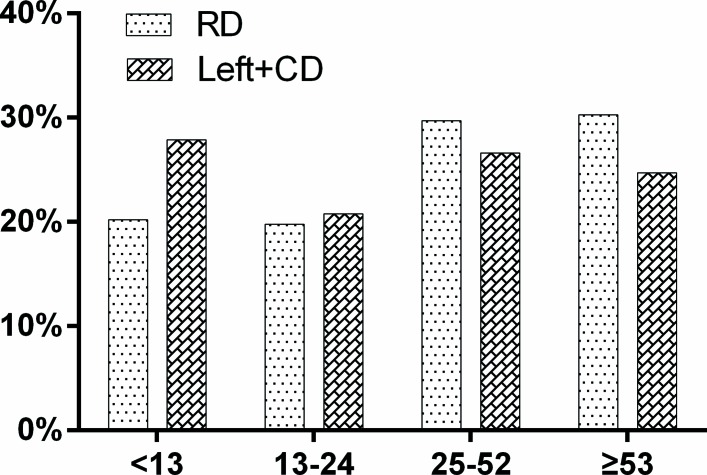

Association between Gensini score and coronary dominance

The total Gensini score was significantly higher in the RD group than in the left-CD group (42.3±33.6 vs 36.3±29.8; p=0.033). Also, patients in the RD group have a higher Gensini score than patients in the left-CD groups in RCA (p<0.001) and posterior descending artery (p=0.013) (table 2). In addition, RD tended to have higher proportion in the third and fourth grade of the Gensini score (figure 1).

Table 2.

Gensini score and coronary dominance

| RD (n=1500) |

Left+CD (n=154) |

P values | |

| Age (years) | 59.4±10.4 | 59.2±9.5 | 0.769 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.242 | ||

| Male | 1114 (74.3) | 121 (78.6) | |

| Female | 386 (25.7) | 33 (21.4) | |

| Baseline SBP (mm Hg) | 134.8±21.2 | 132.6±19.5 | 0.231 |

| Baseline DBP (mm Hg) | 78.4±12.4 | 78.1±11.0 | 0.819 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 75.4±13.1 | 76.5±14.8 | 0.341 |

| CAD risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 295 (19.7) | 26 (16.9) | 0.406 |

| Hypertension | 797 (53.1) | 73 (47.4) | 0.175 |

| Current smoking | 758 (50.5) | 83 (53.9) | 0.427 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 164 (10.9) | 18 (11.7) | 0.776 |

| Total Gensini score | 42.3±33.6 | 36.3±29.8 | 0.033 |

| LM | 1.7±7.3 | 1.7±7.7 | 0.935 |

| LAD | 21.1±21.1 | 19.7±20.0 | 0.433 |

| RCA | 7.8±10.8 | 4.7±8.5 | <0.001 |

| LCx | 9.1±14.5 | 8.2±12.4 | 0.424 |

| Diagonal branch | 1.3±2.7 | 1.1±2.4 | 0.402 |

| Septal branch | 0.1±0.5 | 0.1±0.8 | 0.491 |

| OM | 0.7±2.2 | 0.6±2.0 | 0.848 |

| Posterior descending artery | 0.6±2.1 | 0.2±1.5 | 0.013 |

bpm, beats per minute; CAD, coronary artery disease; CD, codominance; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LAD, left anterior descending branch; LCx, left circumflex branch; LM, left main coronary artery; OM, obtuse marginal branch; RCA, right coronary artery; RD, right dominance; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure 1.

Distribution of RD and left-CD groups in different grades of Gensini score. CD, codominance; RD, right dominance.

Univariate linear regression analysis showed that RD, age, gender, diabetes and heart rate were associated with increasing Gensini score (table 3). After adjusting for age, gender, diabetes and heart rate, RD (β=6.699, 95% CI 1.193 to 12.205, p=0.017) was positively associated with the Gensini score of patients (table 4). The final multiple linear regression model also showed a positive correlation between RD and Gensini score.

Table 3.

Univariate linear regression analysis for Gensini score

| Variable | β (95% CI) | P values |

| Right dominance | 5.991 (0.474 to 11.508) | 0.033 |

| Age | 0.187 (0.033 to 0.342) | 0.017 |

| Male | 9.811 (6.150 to 13.472) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 1.098 (−2.113 to 4.309) | 0.503 |

| Hypertension | 1.033 (−2.182 to 4.247) | 0.529 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8.408 (4.369 to 12.447) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | −2.038 (−7.167 to 3.091) | 0.436 |

| Family history of CAD | −0.652 (−4.200 to 2.896) | 0.719 |

| SBP | −0.065 (−0.142 to 0.013) | 0.100 |

| DBP | −0.008 (−0.141 to 0.125) | 0.911 |

| Heart rate | 0.148 (0.025 to 0.271) | 0.018 |

CAD, coronary artery disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regression analysis for Gensini score

| Variable | β (95% CI) | P values |

| Unadjusted | 5.991 (0.474 to 11.508) | 0.033 |

| Model 1 | 6.404 (0.945 to 11.862) | 0.022 |

| Model 2 | 6.699 (1.193 to 12.205) | 0.017 |

| Model 3 | 6.829 (1.312 to 12.346) | 0.015 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and gender.

Model 2: adjusted for age and gender, diabetes, and heart rate.

Model 3: adjusted for age and gender, diabetes, heart rate, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, history of coronary artery disease, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure.

Discussion

Coronary circulation is categorised as RD, LD and CD according to the blood supply of the posterior IVS using CAG or CT-CAG.4 Previous studies have shown that coronary artery dominance was closely related to cardiovascular outcomes.4 A study of 1131 patients showed that LD was associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality and early reinfarction after ST-elevated myocardial infarction.24 Goldberg et al 7 demonstrated that LD was a risk factor for increased long-term mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome. However, little is known about the role of RD in CAD. In this study, we found that RD was associated with the severity of CAD. The results indicated that RD was more prone to have serious CAD stenosis and may serve as a marker of CAD severity.

In the general population, RD anatomy has a prevalence of approximately 70%.10 In addition, LD and RD have a reported prevalence of approximately 5%–12% and 82%–89%, respectively, whereas CD is found in 3%–7% of individuals based on a hospital population.5–7 25 26 The proportion of RD, LD and CD in our study was 90.6%, 6.7% and 2.7%, respectively. The phenomenon reminds us that the RD group may have higher percentage in a hospital population than in the general population.

The Gensini score is a quick and easy way to quantify the severity of CAD in the clinical work. Therefore, we used this scoring system to further investigate the association between coronary dominance and CAD. In our study, the total Gensini score of an RD patient was obviously higher than a patient with left-CD. After multiple linear regression, RD showed a positive correlation with Gensini score. A previous study with a large population found a higher prevalence of triple vessel disease in patients with RD than in patients with LD.26 The result indicated that patients with RD tended to have more serious coronary stenosis. At present, the mechanism between RD and the severity of CAD is still not known. Therefore, further research is needed to detect the underlying mechanism for developing more severe lesions in patients with RD.

Some potential limitations in this study should be noted. First, our finding was based on a Northern Chinese population. Therefore, the results should not be extended to all ethnic groups. Second, our data were obtained from a hospital database, so the outcomes of patients were unavailable. Finally, the study population was relatively small, which led to a smaller group of individuals with LD and CD.

Conclusion

The present study reported that patients with RD had a significantly higher proportion of serious coronary stenosis than patients with LD and CD. Right coronary dominance was associated with the severity of CAD. A prospective, multicentre cohort study may further validate our findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Qiaolong Hu, Jinni Li, Jian Kang, Chuance Yang, Li Bai, Yufeng Wang and Wan Gao from Xi’an Jiaotong University School of Medicine for contributing to the data collection. We also acknowledge the support from the patients who participated in our research.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design, writing and review of the report. BY, JY, QM and LY collected the data. BZ and YF did the primary data analysis, and JY, BY and XM participated in further data analysis. XM handled supervision in our study. All authors approved the final version of the report.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 81471374) and the Clinical Research Award of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China (grant number: XJTU1AF-CRF-2016-005).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature 1993;362:801–9. 10.1038/362801a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Drozda J, Messer JV, Spertus J, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 performance measures for adults with coronary artery disease and hypertension: a report of the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on performance measures and the American medical association-physician consortium for performance improvement. Circulation 2011;124:248–70. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821d9ef2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sinning C, Lillpopp L, Appelbaum S, et al. Angiographic score assessment improves cardiovascular risk prediction: the clinical value of SYNTAX and gensini application. Clin Res Cardiol 2013;102:495–503. 10.1007/s00392-013-0555-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Veltman CE, de Graaf FR, Schuijf JD, et al. Prognostic value of coronary vessel dominance in relation to significant coronary artery disease determined with non-invasive computed tomography coronary angiography. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1367–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuno T, Numasawa Y, Miyata H, et al. Impact of coronary dominance on in-hospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome. PLoS One 2013;8:e72672 10.1371/journal.pone.0072672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parikh NI, Honeycutt EF, Roe MT, et al. Left and codominant coronary artery circulations are associated with higher in-hospital mortality among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes: report from the national cardiovascular database Cath Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CathPCI) Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:775–82. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldberg A, Southern DA, Galbraith PD, et al. Coronary dominance and prognosis of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J 2007;154:1116–22. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Altin C, Kanyilmaz S, Koc S, et al. Coronary anatomy, anatomic variations and anomalies: a retrospective coronary angiography study. Singapore Med J 2015;56:339–45. doi:10.11622/smedj.2014193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abuchaim DC, Tanamati C, Jatene MB, et al. Coronary dominance patterns in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 2011;26:604–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pelter MM, Al-Zaiti SS, Carey MG. Coronary artery dominance. American Journal of Critical Care 2011;20:401–2. 10.4037/ajcc2011734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abu-Assi E, Castiñeira-Busto M, González-Salvado V, et al. Coronary artery dominance and long-term prognosis in patients With ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty. Rev Esp Cardiol 2016;69:19–27. 10.1016/j.rec.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waziri H, Jørgensen E, Kelbæk H, et al. Acute myocardial infarction and lesion location in the left circumflex artery: importance of coronary artery dominance. EuroIntervention 2016;12:441–8. 10.4244/EIJY15M09_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Veltman CE, van der Hoeven BL, Hoogslag GE, et al. Influence of coronary vessel dominance on short- and long-term outcome in patients after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1023–30. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Omerbasic E, Hasanovic A, Omerbasic A, et al. Prognostic value of anatomical dominance of coronary circulation in patients with surgical myocardial revascularization. Med Arch 2015;69:6–9. 10.5455/medarh.2015.69.6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lam MK, Tandjung K, Sen H, et al. Coronary artery dominance and the risk of adverse clinical events following percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the prospective, randomised TWENTE trial. EuroIntervention 2015;11:180–7. 10.4244/EIJV11I2A32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2013;31:1281–357. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vijan S. Type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:ITC3-1–15. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-01003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hou X, Qiu J, Chen P, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with a lower prevalence of newly diagnosed diabetes screened by OGTT than non-smoking in Chinese men with Normal Weight. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149234 10.1371/journal.pone.0149234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the american college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Circulation 2011;124:e574–651. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang GN, Sun K, Hu DL, et al. Serum cystatin C levels are associated with coronary artery disease and its severity. Clin Biochem 2014;47:176–81. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yongsakulchai P, Settasatian C, Settasatian N, et al. Association of combined genetic variations in PPARγ, PGC-1α, and LXRα with coronary artery disease and severity in thai population. Atherosclerosis 2016;248:140–8. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu H, Guan S, Fang W, et al. Associations between pentraxin 3 and severity of coronary artery disease. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007123 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ndrepepa G, Tada T, Fusaro M, et al. Association of coronary atherosclerotic burden with clinical presentation and prognosis in patients with stable and unstable coronary artery disease. Clin Res Cardiol 2012;101:1003–11. 10.1007/s00392-012-0490-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stribling WK, Kontos MC, Abbate A, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with acute left circumflex/obtuse marginal occlusion presenting with myocardial infarction. J Interv Cardiol 2011;24:27–33. 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2010.00599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eren S, Bayram E, Fil F, et al. An investigation of the association between coronary artery dominance and coronary artery variations with coronary arterial disease by multidetector computed tomographic coronary angiography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2008;32:929–33. 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181593d5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vasheghani-Farahani A, Kassaian SE, Yaminisharif A, et al. The association between coronary arterial dominancy and extent of coronary artery disease in angiography and paraclinical studies. Clin Anat 2008;21:519–23. 10.1002/ca.20669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.