Abstract

Objective

To investigate socioeconomic differences in six perinatal health outcomes in Denmark in the first decade of the 21st century.

Design

A population-based cohort study.

Setting

Danish national registries.

Participants

A total of 646 829 live born children and 3076 stillborn children (≥22+0 weeks of gestation) born in Denmark from 2000 to 2009. We excluded children with implausible relations between birth weight and gestational age (n=644), children without information on maternal country of origin (n=138) and implausible values of maternal year of birth (n=36).

Main outcome measures

We investigated the following perinatal health outcomes: stillbirth, neonatal and postneonatal mortality, small-for-gestational age, preterm birth grated into moderate preterm, very preterm and extremely preterm, and congenital anomalies registered in the first year of life.

Results

Maternal educational level was inversely associated with all adverse perinatal outcomes. For all examined outcomes, the risk association displayed a clear gradient across the educational levels. The associations remained after adjustment for maternal age, maternal country of origin and maternal year of birth. Compared with mothers with vocational education, mothers with more than 15 years of education had an adjusted risk ratio for stillbirth of 0.64(95% CI 0.56 to 0.72). The corresponding adjusted risk ratios for neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality, congenital anomalies, moderate preterm birth and small-for-gestational age were, respectively, 0.79(95% CI 0.67 to 0.93), 0.57(95% CI 0.42 to 0.78), 0.87(95% CI 0.83 to 0.91), 0.80(95% CI 0.77 to 0.83) and 0.83(95% CI 0.81 to 0.85).

Conclusion

Substantial educational inequalities in perinatal health were still present in Denmark in the first decade of the 21st century.

Keywords: health inequalities, congenital anomalies, preterm birth, small-for-gestational age, stillbirth, infant mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Danish national registries with high degree of completeness and quality were used in this study.

The large study population enabled investigation of rare perinatal outcomes.

The grading of maternal education into five categories enabled detailed investigation of the educational gradients.

Congenital anomalies are not registered for stillbirths and spontaneous abortions during the study period and as a consequence we could only estimate risk among live born children.

Introduction

The Nordic countries are generally regarded as egalitarian and have a low prevalence of adverse perinatal outcomes. However in the 1980s and 1990s, strong socioeconomic gradients in adverse perinatal outcomes were observed in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Several studies documented socioeconomic inequalities in respectively stillbirth, preterm birth, birth weight, infant mortality in all of the Nordic countries1–4 but studies have been inconclusive with regard to congenital anomalies.5–8

During the first decade of the 21st century, economic inequality rose in Denmark and elsewhere,9–11 but it is unclear what impact this has had on inequalities in perinatal health. Perinatal health measures, such as infant mortality, are used internationally as indicators of population health status. In addition, perinatal outcomes such as preterm birth and fetal growth are predictive at the individual level for health later in life. Several studies have found that low birth weight is related to the risk of chronic diseases in adulthood, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.12 13 The health condition of the mother affects perinatal outcomes, thereby transferring socioeconomic inequality in health from one generation to the next.13

Socioeconomic position refers to the economic and social indicators that influence what positions individuals or groups hold within the structure of a society.14 In this study, educational level has been chosen as a measure of socioeconomic position because education is a favourable indicator of socioeconomic position in early adult life. Furthermore, education is associated to future occupational status and income.15

The aim of this study was to describe the associations between maternal educational level and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes in Denmark during the first decade of the 21st century. The adverse perinatal outcomes of interest in this study were stillbirth, preterm birth, small-for-gestational age (SGA), congenital anomalies, neonatal mortality and postneonatal mortality.

Methods

We did a longitudinal register linkage study of all live births and stillbirths in Denmark from 2000 to 2009, as recorded in the Danish Medical Birth Register. Information on maternal educational level from the Population’s Education register16 was linked to information on perinatal health outcomes from the Danish Medical Birth Register,17 the Danish National Patient Register18 and the Danish Register of Causes of Death.19 The Danish system of unique person identifiers was used to link individuals across the different registers in an anonymised dataset in Statistics Denmark which could be assessed via a vitual private network connection from Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen.

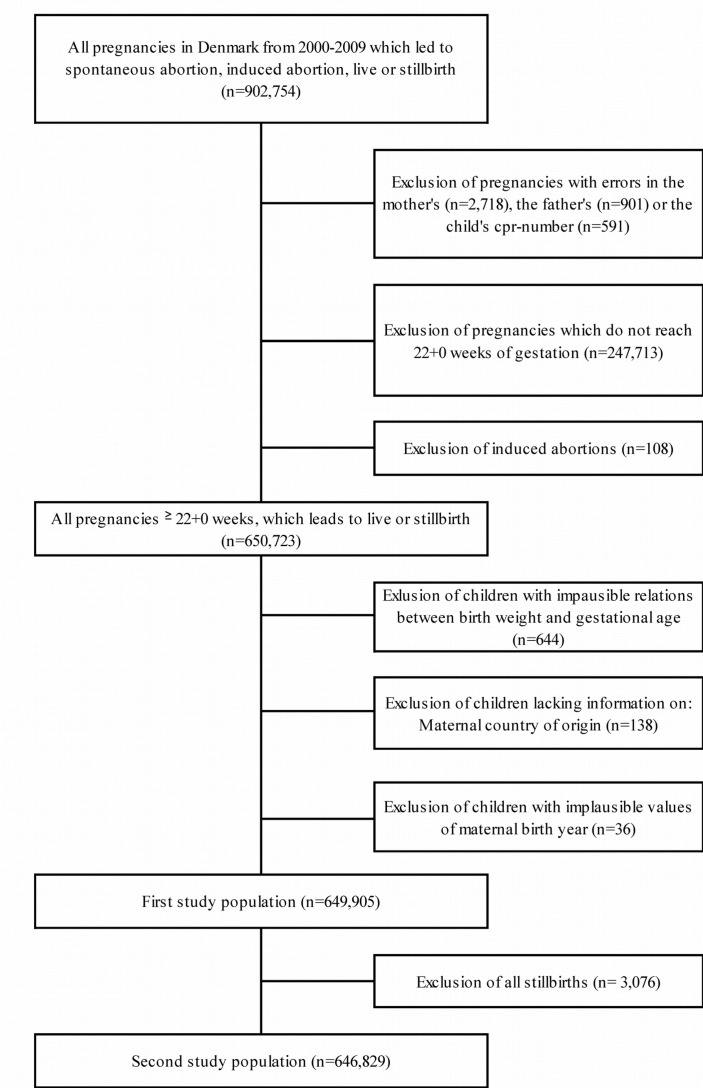

Study populations

The study population consisted of all live born and stillborn children born in Denmark during the study period. Children were excluded from the study population as illustrated in figure 1. Children whose mothers were born after 1999 were excluded. Furthermore, we excluded children with implausible relations between gestational age and birth weight defined according to the method described by Alexander et al.20 After the exclusions, study population 1 consisted of a total of 649 905 live and stillborn children. Study population 2 consisted of 646 829 live born when stillborn children were excluded from study population 1. In the analysis of SGA, children with missing information on birth weight (n=4388) were not included.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study populations.

Patient and public involvement

As this is a whole population register-based study, we did not recruit individuals. Patients and public were not involved in the development of the research question, the design or conduct of this study. We planned to disseminate the results of this study through open-access publication.

Study variables

The main exposure variable of interest was maternal educational level, defined as the highest educational level attained or expected (based on ongoing education) of the mother at the year of birth categorised into five categories: primary education (≤9 years), secondary education (high school 10-12 years), vocational education (10-12 years), short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education (12-15 years), long-cycle higher education (>15 years) and missing. Since the education register is based on reports from Danish educational institutions, the category of missing is composed of individuals who are not registered at any education in Denmark.

Information on birth weight and the outcomes preterm birth and stillbirth were obtained from the Medical Birth Register. SGA was defined as birth weight falling below the 10th percentile of birth weight according to sex-specific intrauterine growth curves presented by Marsàl et al.21 Preterm birth was divided into extremely preterm birth defined as birth ≥22+0–27+6 weeks, very preterm birth defined as birth ≥28+0–31+6 and moderately preterm birth defined as birth ≥32+0–36+6. The variable stillbirth was defined as fetal death at or after 22 completed gestational weeks. In Denmark, the threshold between spontaneous abortions and stillbirths was changed in 2004 from 28 completed weeks of gestation to 22 completed weeks of gestation. All pregnancies from 2000 to 2003 for which a spontaneous abortion was registered after 22 completed weeks of gestation were recoded into stillbirths. Information on infant mortality was obtained from The Central Person Register and The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Neonatal mortality was defined as death of a live born child before or at day 27 after birth, and postneonatal mortality was defined as death of a live born child at day 28 through day 365 after birth. Information on congenital anomalies was obtained from the Danish National Patient Register. The variable congenital anomalies registered in the first year of life were defined according to EuroCAT’s definitions excluding minor anomalies according to EuroCAT criteria.22

Other potential confounders in the analysis were the maternal year of birth (<1965, 1965-69, 1970-74, 1975-79, ≥1980), maternal age at the time of delivery (<25 years, 25-29 years, 30-34 years, 35-39 years, ≥40 years), offspring’s year of birth (2000-01, 2002-03, 2004-05, 2006-07, 2008-09) and country of origin of the mother categorised as Denmark, ‘Other western country’ (Andorra, Australia, Canada, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, San Marino, Switzerland, the USA, Vatican City State and all European Union member countries except Denmark) or ‘Non-western country’ (all remaining countries).

Statistics

Initially, we calculated the prevalence for the six perinatal outcomes by maternal educational level. To investigate the associations between maternal educational level and the perinatal outcomes, we used multiple logistic regression analyses, and the analysis populations were restricted to children with information on maternal educational level. The a priori chosen model for adjustment included the covariates maternal age, maternal country of origin and maternal year of birth as these were considered potential confounders. The variable year of birth of the offspring was not included in the model since the variables maternal age at the time of delivery and maternal year of birth in combination practically describe the variable. Unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios (RR) were presented with a 95% CI. Additionally, we fitted two models to test robustness of the findings: one adjusted for maternal age only and the second including maternal age, parity and country of origin, and maternal year of birth as covariates. However, since the findings from the two models fitted to test robustness were similar to findings from the other adjusted model, their findings were not shown. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS V.9.4.

Results

The distributions of maternal educational level by maternal age, maternal year of birth, maternal country of origin and calendar year of birth are presented in table 1. In Denmark, maternal completed and ongoing educational level increased during the study period as shown in table 1. The proportion of mothers born outside Denmark was higher among mothers with missing educational level.

Table 1.

Maternal age, year of birth and country of origin, and offspring’s year of birth by educational level, all children born in Denmark, 2000–2009

| All children n=649 905 | Primary education n=106 129 | Vocational education n=222 744 | Secondary education n=46 026 | Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education n=185 417 | Long-cycle higher education n=94 168 | Missing n=15 421 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Maternal age | |||||||

| <25 | 12.3 | 32.6 | 12.2 | 17.8 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 20.0 |

| 25–29 | 33.5 | 30.9 | 37.4 | 31.2 | 25.4 | 26.2 | 34.6 |

| 30–34 | 36.3 | 23.0 | 34.5 | 32.6 | 42.1 | 46.9 | 28.0 |

| 35–39 | 15.3 | 11.0 | 13.8 | 15.8 | 16.4 | 21.1 | 14.0 |

| ≥40 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 3.4 |

| Maternal year of birth | |||||||

| <1965 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.5 |

| 1965–69 | 16.5 | 12.3 | 16.4 | 17.6 | 17.0 | 20.7 | 12.6 |

| 1970–74 | 33.5 | 24.0 | 33.0 | 32.4 | 37.6 | 39.6 | 24.2 |

| 1975–79 | 30.6 | 28.8 | 32.0 | 27.9 | 31.8 | 28.3 | 31.1 |

| ≥1980 | 15.2 | 30.8 | 14.8 | 17.6 | 9.8 | 6.7 | 27.7 |

| Maternal country of origin | |||||||

| Denmark | 86.2 | 74.7 | 91.0 | 77.6 | 93.2 | 92.0 | 10.7 |

| Western countries | 3.1 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 26.3 |

| Non-western countries | 10.7 | 24.0 | 7.2 | 18.6 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 63.0 |

| Year of birth (offspring) | |||||||

| 2000–2001 | 20.5 | 24.2 | 22.3 | 23.7 | 17.9 | 16.0 | 20.2 |

| 2002–2003 | 19.9 | 21.1 | 20.9 | 22.1 | 18.8 | 18.0 | 14.9 |

| 2004–2005 | 20.0 | 19.6 | 20.1 | 20.1 | 20.6 | 20.0 | 12.6 |

| 2006–2007 | 20.0 | 18.0 | 19.1 | 18.2 | 21.5 | 22.2 | 21.0 |

| 2008–2009 | 19.7 | 17.1 | 17.7 | 15.9 | 21.2 | 23.8 | 31.3 |

The prevalence of stillbirth, neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality, congenital anomalies, SGA and three degrees of preterm birth, respectively, by maternal educational level are shown in table 2. Women with the shortest education had a higher prevalence of all of the adverse perinatal outcomes compared with women with higher educational level. The group of women with unknown educational level had the highest prevalence of stillbirth and SGA compared with the women with known educational level.

Table 2.

Prevalence of adverse perinatal outcome by educational level, Denmark, 2000–2009

| Stillbirth | Neonatal mortality | Postneonatal mortality | Congenital anomalies | SGA | Moderate preterm birth 32+0–36+6 |

Very preterm birth 28+0–31+6 |

Extreme preterm birth <28+0 | |

| n=3076 | n=1688 | n=648 | n=19 449 | n=59 979 | n=36 610 | n=4670 | n=1843 | |

| Per 1000 | Per 1000 | Per 1000 | Per 1000 | Per 1000 | Per 1000 | Per 1000 | Per 1000 | |

| Primary education | 6.7 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 34.9 | 125.9 | 64.5 | 8.3 | 4.1 |

| Vocational education | 4.8 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 30.7 | 95.1 | 60.0 | 7.8 | 3.0 |

| Secondary education | 4.0 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 28.2 | 94.2 | 52.7 | 7.0 | 2.4 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 4.3 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 28.7 | 77.9 | 53.7 | 6.6 | 2.3 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 3.1 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 27.1 | 77.9 | 48.8 | 6.3 | 2.4 |

| Missing | 7.1 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 28.9 | 126.5 | 51.2 | 5.9 | 3.1 |

SGA, small-for-gestational age.

Table 3 shows the relative risks, expressed as adjusted and unadjusted RR, of respectively stillbirth, neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality, congenital anomalies, SGA and moderately preterm birth, very preterm birth and extremely preterm birth, with mothers with vocational education as the comparison group. Compared with mothers with vocational education, mothers with primary education had a statistically significant increased RR for stillbirth, neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality, congenital anomalies, moderate preterm birth, very preterm birth, extreme preterm birth and SGA. Women with short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education and women with long-cycle higher education had a statistically significant lower risk of all the six perinatal outcomes compared with women with vocational education. These results indicated consistently inverse educational gradients in the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes. The gradients were consistent after adjusting for maternal age, maternal country of origin and maternal year of birth. The estimates were almost identical in analyses with adjustment for maternal age only and with adjustment for maternal age, maternal country of origin, maternal year of birth and parity (results not shown).

Table 3.

Adverse perinatal outcome by maternal educational level, all births, Denmark, 2000–2009

| RR | 95 % CI | aRR | 95 % CI | |

| Stillbirth | ||||

| Primary education | 1.39 | 1.26 to 1.53 | 1.34 | 1.21 to 1.48 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 0.84 | 0.71 to 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.69 to 0.94 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.89 | 0.81 to 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.81 to 0.98 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.65 | 0.57 to 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.56 to 0.72 |

| Neonatal mortality | ||||

| Primary education | 1.33 | 1.16 to 1.51 | 1.29 | 1.12 to 1.47 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 0.92 | 0.76 to 1.13 | 0.90 | 0.73 to 1.10 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.79 | 0.70 to 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.71 to 0.92 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.79 | 0.67 to 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.67 to 0.93 |

| Postneonatal mortality* | ||||

| Primary education | 1.93 | 1.59 to 2.35 | 1.81 | 1.47 to 2.22 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 1.02 | 0.74 to 1.41 | 0.98 | 0.71 to 1.36 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.74 | 0.59 to 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.61 to 0.95 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.55 | 0.41 to 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.42 to 0.78 |

| Congenital anomalies | ||||

| Primary education | 1.14 | 1.09 to 1.18 | 1.13 | 1.08 to 1.18 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 0.92 | 0.86 to 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.86 to 0.97 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.94 | 0.90 to 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.90 to 0.97 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.83 to 0.91 |

| Moderate preterm birth, 32+0 to 36+6† | ||||

| Primary education | 1.07 | 1.04 to 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.08 to 1.14 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.86 to 0.93 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.89 | 0.87 to 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.86 to 0.91 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.81 | 0.79 to 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.77 to 0.83 |

| Very preterm birth, 28+0 to 31+6† | ||||

| Primary education | 1.06 | 0.98 to 1.15 | 1.10 | 1.01 to 1.20 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 0.89 | 0.79 to 1.01 | 0.91 | 0.81 to 1.03 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.83 | 0.77 to 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.76 to 0.89 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.80 | 0.73 to 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.71 to 0.86 |

| Extreme preterm birth, <28+0† | ||||

| Primary education | 1.36 | 1.20 to 1.54 | 1.35 | 1.19 to 1.54 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 0.79 | 0.64 to 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.63 to 0.96 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.77 | 0.68 to 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.67 to 0.86 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.78 | 0.67 to 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.65 to 0.89 |

| SGA | ||||

| Primary education | 1.32 | 1.30 to 1.35 | 1.25 | 1.22 to 1.28 |

| Vocational education | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary education | 0.99 | 0.96 to 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.93 to 0.99 |

| Short-cycle and medium-cycle higher education | 0.82 | 0.80 to 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.82 to 0.85 |

| Long-cycle higher education | 0.82 | 0.80 to 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.81 to 0.85 |

*Compared with children who were alive 365 days after birth.

†Compared with children born from 37+0–41+6.

aRR, risk ratio adjusted for maternal age, maternal country of origin and maternal year of birth; RR, crude risk ratio; SGA, small-for-gestational age.

Discussion

In a population register study of perinatal outcomes in Denmark, we found consistent inverse educational gradients for all perinatal outcomes in the study period, with higher rates of adverse outcomes in children of women with lower educational levels. Adjustments for maternal age, country of origin, parity and maternal year of birth did not change the gradients.

An educational gradient in SGA was found in this study. This result is consistent with previous Nordic studies which have reported socioeconomic inequalities in SGA.5 23–28 Socioeconomic differences have been found in preterm birth as an overall outcome5 23 24 29 and in preterm birth categorised according to gestational age.3 26 28 30 31 This study found an educational gradient in moderate, very and extreme preterm birth. Consistent with previous studies,32–34 an educational gradient was found in stillbirth in this study. This study observed educational gradients in neonatal and postneonatal mortality. Socioeconomic inequalities have been found in earlier Nordic studies in neonatal mortality28 32 35–38 and also in postneonatal mortality.32 35 36 38

Previous Nordic studies that investigated the association between socioeconomic position and congenital anomalies reported inconsistent results.5–8 In accordance with a previous Danish study,6 this study found a statistically significant educational gradient in congenital anomalies. Both studies used maternal educational level as a measure of socioeconomic position whereas the other studies used occupation5 8 or a combination of occupation and education.7 The differences in findings regarding socioeconomic differences in congenital anomalies are likely to be related to the use of different socioeconomic measures.

We used population-covering register individual-based data with minimal sources of selection and information bias. The data from the Danish Medical Birth Register used in this study are of high quality.17 The size of the study population enabled investigation of relatively rare perinatal outcomes like postneonatal mortality. Information on education was collected for administrative purposes, and according to the documentation from Statistics Denmark, the education variable was a so-called high-quality variable.39 A limitation of this study is that the Danish registers only obtained information on congenital anomalies for live births. The prevalence of congenital anomalies is presumably higher among stillbirths, spontaneous and induced abortions than among live births.40 Consequently, the socioeconomic gradient in congenital anomalies observed in this study could be underestimated. In order to understand the true association between socioeconomic position and congenital anomalies, it is essential to include information on congenital anomalies for live births, stillbirths, induced abortions and spontaneous abortions.

In contrast to several previous studies, we did not adjust for lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol intake, BMI and physical activity. In this study, we were interested in estimating the overall effect of maternal educational level on adverse perinatal outcome and as a consequence we did not adjust for lifestyle factors as these were believed to mediate the association. It could be debated whether maternal age is a mediator or a confounder in the association. In this study, we assumed that maternal age affects maternal education since young women have not had the opportunity to undergo as much education as older women. As a consequence, we considered maternal age as a confounder. Both singletons and multiples were included in the analyses as we did not think the associations between maternal education and the adverse perinatal outcomes differed between singletons and multiples when the estimates were adjusted for maternal age and other potential confounders.

The general level of education in Denmark increased during the study period. The proportion of women who attained primary school and no further education declined slightly during the study period. However, educational inequality in adverse perinatal outcomes was still observed. A contributing explanation of the inequality is likely to be found in a possible selection of women with the lowest educational level.37 The group of women with primary education becomes more highly selected and thereby more socially vulnerable,41 and this may contribute to the higher risk of adverse perinatal outcomes. The educational distribution forwomen who give birth changes over time this makes generalisations to other cohorts difficult. Nevertheless, socioeconomic differences in perinatal outcomes have been observed in different countries and in different time periods.4

Educational inequality in perinatal outcomes persists in the 21st century. A possible part of the explanation of this is an overall healthier lifestyle among women with higher socioeconomic position. Certain lifestyle risk factors are more common among lower socioeconomic groups than among higher socioeconomic groups. For instance, the prevalence of smokers is highest among women with lower educational level in Denmark,42 and smoking is associated with a higher risk of several adverse perinatal outcomes.40 To investigate the mediating factors between socioeconomic position and adverse perinatal outcomes was beyond the scope of this article. However, in order to reduce socioeconomic inequality in perinatal health, future studies should focus on the mediating mechanisms in the association of socioeconomic position and adverse perinatal outcome.

Conclusion

Socioeconomic inequality in perinatal health was observed in Denmark in the first decade of the 21st century. Maternal educational gradients were evident in the rare but serious outcomes such as congenital anomalies and fetal and infant mortality. The socioeconomically patterned risk of preterm birth and growth restriction is worrying because it may be the first tracks on the way to socioeconomic inequalities in health later in life. Interventions to diminish socioeconomic inequality in the earliest phases of life are still needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor David Taylor Robinson for his comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Contributors: A-MNA, JBA and JFB designed the study. JAB and JFB analysed the data with assistance from A-MNA, AVH and LHM. JBA and JFB interpreted the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript which was revised by A-MNA, AVH and LHM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project was partly supported by the NordForsk grant no. 75970 for the project Contingent Life Courses.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: According to Danish legislation, no ethical permission is required for register-based research; however, this study was approved by the local data protection authorities.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Denmark but restrictions apply to the availability of these data which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Statistics Denmark.

References

- 1. Rom AL, Mortensen LH, Cnattingius S, et al. A comparative study of educational inequality in the risk of stillbirth in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden 1981-2000. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:240–6. 10.1136/jech.2009.101188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arntzen A, Nybo Andersen AM. Social determinants for infant mortality in the Nordic countries, 1980-2001. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:381–9. 10.1080/14034940410029450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petersen CB, Mortensen LH, Morgen CS, et al. Socio-economic inequality in preterm birth: a comparative study of the Nordic countries from 1981 to 2000. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:66–75. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mortensen LH, Helweg-Larsen K, Andersen AM. Socioeconomic differences in perinatal health and disease. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:110–4. 10.1177/1403494811405096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Räisänen S, Sankilampi U, Gissler M, et al. Smoking cessation in the first trimester reduces most obstetric risks, but not the risks of major congenital anomalies and admission to neonatal care: a population-based cohort study of 1 164 953 singleton pregnancies in Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:159–64. 10.1136/jech-2013-202991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olesen C, Thrane N, Rønholt A-M, et al. Association between social position and congenital anomalies: A population-based study among 19,874 Danish women. Scand J Public Health 2009;37:246–51. 10.1177/1403494808100938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Varela MM, Nohr EA, Llopis-González A, et al. Socio-occupational status and congenital anomalies. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:161–7. 10.1093/eurpub/ckp003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morales-Suárez-Varela M, Kaerlev L, Zhu JL, et al. Unemployment and pregnancy outcomes: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:449–56. 10.1177/1403494811407672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piketty T, Goldhammer A. Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. OECD. An overview of growing income inequalities in OECD countries: Main Findings. Divid We Stand Why Inequal Keeps Rising 2011;25:21–45. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Statistics Denmark. Indkomster 2011. Denmark: Statistics Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fall CH. Fetal programming and the risk of noncommunicable disease. Indian J Pediatr 2013;80 Suppl 1:13–20. 10.1007/s12098-012-0834-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, et al. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:61–73. 10.1056/NEJMra0708473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lynch J, Kaplan G. Socioeconomic position In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds Social Epidemiology, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:7–12. 10.1136/jech.2004.023531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish Education Registers. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:91–4. 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegård A, et al. The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur J Epidemiol 2018;33:27–36. 10.1007/s10654-018-0356-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:26–9. 10.1177/1403494811399958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, et al. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:163–8. 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marsál K, Persson PH, Larsen T, et al. Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr 1996;85:843–8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eurocat, EUROCAT Guide 1.4 and reference documents. 2013. http://www.eurocat-network.eu/content/Full%20Guide%201%204.pdf.

- 23. Gissler M, Rahkonen O, Arntzen A, et al. Trends in socioeconomic differences in Finnish perinatal health 1991-2006. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:420–5. 10.1136/jech.2008.079921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mortensen LH, Lauridsen JT, Diderichsen F, et al. Income-related and educational inequality in small-for-gestational age and preterm birth in Denmark and Finland 1987-2003. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:40–5. 10.1177/1403494809353820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Räisänen S, Gissler M, Sankilampi U, et al. Contribution of socioeconomic status to the risk of small for gestational age infants--a population-based study of 1,390,165 singleton live births in Finland. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:28 10.1186/1475-9276-12-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Parental occupation and risk of small-for-gestational-age births: a nationwide epidemiological study in Sweden. Hum Reprod 2010;25:1044–50. 10.1093/humrep/deq004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mortensen LH, Diderichsen F, Arntzen A, et al. Social inequality in fetal growth: a comparative study of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden in the period 1981-2000. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:325–31. 10.1136/jech.2007.061473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gisselmann MD, Hemström O. The contribution of maternal working conditions to socio-economic inequalities in birth outcome. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1297–309. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thompson JM, Irgens LM, Rasmussen S, et al. Secular trends in socio-economic status and the implications for preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2006;20:182–7. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morgen CS, Bjørk C, Andersen PK, et al. Socioeconomic position and the risk of preterm birth-a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1109–20. 10.1093/ije/dyn112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Räisänen S, Gissler M, Saari J, et al. Contribution of risk factors to extremely, very and moderately preterm births - register-based analysis of 1 390 742 singleton births. PLoS One 2013;8:e60660 10.1371/journal.pone.0060660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carlsen F, Grytten J, Eskild A. Maternal education and risk of offspring death; changing patterns from 16 weeks of gestation until one year after birth. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:157–62. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Högberg L, Cnattingius S. The influence of maternal smoking habits on the risk of subsequent stillbirth: is there a causal relation? BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;114:699–704. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01340.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kesmodel U, Wisborg K, Olsen SF, et al. Moderate alcohol intake during pregnancy and the risk of stillbirth and death in the first year of life. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:305–12. 10.1093/aje/155.4.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arntzen A, Mortensen L, Schnor O, et al. Neonatal and postneonatal mortality by maternal education--a population-based study of trends in the Nordic countries, 1981-2000. Eur J Public Health 2008;18:245–51. 10.1093/eurpub/ckm125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arntzen A, Samuelsen SO, Bakketeig LS, et al. Socioeconomic status and risk of infant death. A population-based study of trends in Norway, 1967-1998. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:279–88. 10.1093/ije/dyh054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gisselmann MD, Education GMD. Education, infant mortality, and low birth weight in Sweden 1973-1990: emergence of the low birth weight paradox. Scand J Public Health 2005;33:65–71. 10.1080/14034940410028352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johansson S, Villamor E, Altman M, et al. Maternal overweight and obesity in early pregnancy and risk of infant mortality: a population based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ 2014;349:g6572 10.1136/bmj.g6572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Højkvalitetsvariable. http://www.dst.dk/da/TilSalg/Forskningsservice/Dokumentation/hoejkvalitetsvariable (accessed 20 May 2015).

- 40. Wilcox AJ. Fertility and pregnancy: an epidemiologic perspective. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mortensen LH, Diderichsen F, Davey Smith G, et al. Time is on whose side? Time trends in the association between maternal social disadvantage and offspring fetal growth. A study of 1 409 339 births in Denmark, 1981-2004. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:281–5. 10.1136/jech.2008.076364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Illemann Christensen A. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed. Sundhed og sygelighed i Danmark 2010 & udviklingen siden 1987 . Statens Institut for Folkesundhed 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.