Abstract

PURPOSE

Continuity of care is a defining characteristic of primary care associated with lower costs and improved health equity and care quality. However, we lack provider-level measures of primary care continuity amenable to value-based payment, including the Medicare Quality Payment Program (QPP). We created 4 physician-level, claims-based continuity measures and tested their associations with health care expenditures and hospitalizations.

METHODS

We used Medicare claims data for 1,448,952 beneficiaries obtaining care from a nationally representative sample of 6,551 primary care physicians to calculate continuity scores by 4 established methods. Patient-level continuity scores attributed to a single physician were averaged to create physician-level scores. We used beneficiary multilevel models, including beneficiary controls, physician characteristics, and practice rurality to estimate associations with total Medicare Part A & B expenditures (allowed charges, logged), and any hospitalization.

RESULTS

Our continuity measures were highly correlated (correlation coefficients ranged from 0.86 to 0.99), with greater continuity associated with similar outcomes for each. Adjusted expenditures for beneficiaries cared for by physicians in the highest Bice-Boxerman continuity score quintile were 14.1% lower than for those in the lowest quintile ($8,092 vs $6,958; β = –0.151; 95% CI, –0.186 to –0.116), and the odds of hospitalization were 16.1% lower between the highest and lowest continuity quintiles (OR = 0.839; 95% CI, 0.787 to 0.893).

CONCLUSIONS

All 4 continuity scores tested were significantly associated with lower total expenditures and hospitalization rates. Such indices are potentially useful as QPP measures, and may also serve as proxy resource-use measures, given the strength of association with lower costs and utilization.

Key words: continuity, primary care, measurement

INTRODUCTION

The Institute of Medicine labeled continuity of care a defining characteristic of primary care, one that Starfield and others demonstrated as essential to primary care’s positive impact on health equity, cost reduction, and improved quality of care.1-4 Described as an implicit contract between physician and patient in which the physician assumes ongoing responsibility for the patient,5 continuity frames the personal nature of medical care, in contrast to the dehumanizing nature of disjointed care.6 Building on the idea that knowledge, trust, and respect have developed between the patient and provider over time, allowing for better interaction and communication,7 continuity at the patient level is associated with a host of benefits.8

Primary care has more measures than any other sector under the federal Quality Payment Program (QPP), yet most of these are disease specific or process measures that do not capture the core primary care functions. Despite a variety of definitions and calculations over the last 40 years, little has been done to operationalize continuity as a quality measure linked to policy-relevant outcomes in the United States or other nations.9 Given current US attention to provider-level, vs practice-level, measures in its value-based purchasing reforms, the objective of our study was to examine the relationship between physician-level continuity and health care expenditures and hospitalizations.

METHODS

Sample

We used US Medicare claims data for 1,448,952 beneficiaries obtaining primary care in 2011 from a nationally representative sample of primary care physicians (n = 6,551), including family physicians, general practitioners, and general internists (but not geriatricians) to calculate patient-level primary care continuity scores for 4 measures (Usual Provider Continuity [UPC] index,10 Bice-Boxerman Continuity of Care [BB-COC],11 Modified Modified Continuity Index [MMCI],12 and the Herfindahl Index [HI]13). These 4 measures were selected after a comprehensive review of relevant literature found them to be the most richly described and commonly used measures of continuity. They build on slightly different domains: (1) the density of visits with a provider (UPC), (2) the dispersion of visits among various providers (UPC, BB-COC, MMCI), and (3) the concentration of visits with a particular provider (HI). Consistent with prior approaches, we assigned each beneficiary to the single primary care physician who provided the most outpatient primary care visits to that beneficiary.14 We excluded hospitalists using methods previously described,15 beneficiaries aged less than 65 years with 1 or fewer primary care visits, and physicians with fewer than 30 beneficiaries.

Continuity Measures

For all patients with 2 or more visits, we calculated 4 measures of continuity from utilization data. Patient-level continuity scores were then averaged to produce physician-level scores using each of the 4 measures. Scores were weighted by number of visits, thereby increasing continuity scores for beneficiaries obtaining more primary care.

Variables

We used 2 outcome measures: (1) the natural log of total spending based on allowed charges for Part A (inpatient, skilled nursing, hospice care) and Part B (outpatient doctor visits, laboratories, x-rays, preventive services); and (2) whether or not the beneficiary was hospitalized in 2011. We constructed a modified Charlson score16 and count of the number of primary care visits for each patient. Using the zip code where the primary care physician provided most of their care, we created 2 measures: (1) rurality, using Rural Urban Commuting Area Codes categories (urban, large rural, small rural, isolated rural/frontier)17; and (2) region. Physician specialty information was determined from claims data. From the American Medical Association Masterfile, we determined country of medical school and graduation year.

Analysis

We first used descriptive statistics and simple bivariate analyses to examine the association between the 4 weighted continuity measures and patient, geographic, and physician characteristics. We then estimated beneficiary multilevel models to assess association with expenditures (allowed charges) and hospitalizations that controlled for beneficiary (age, sex, race, Charlson score) and physician characteristics (graduation year, international training, sex, rurality). Given the oversampling of physicians in smaller states, we weighted the data to obtain national estimates. In our examination of expenditures, we used a general linear model with a gamma distribution and log link. For hospitalizations, we used a logistic model. We estimated separate models for each of the 4 continuity measures.

All analyses were done using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp LLC).18 All tests of significance were 2-sided. Significant results were defined at P <.01. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

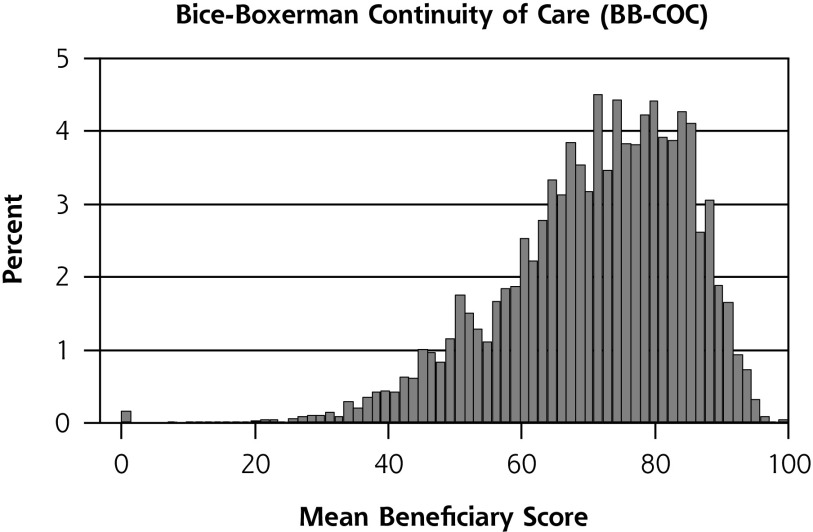

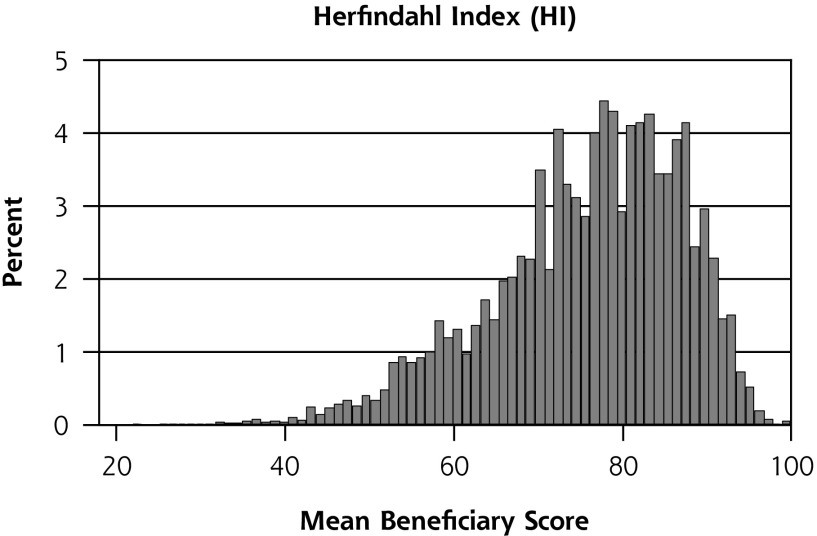

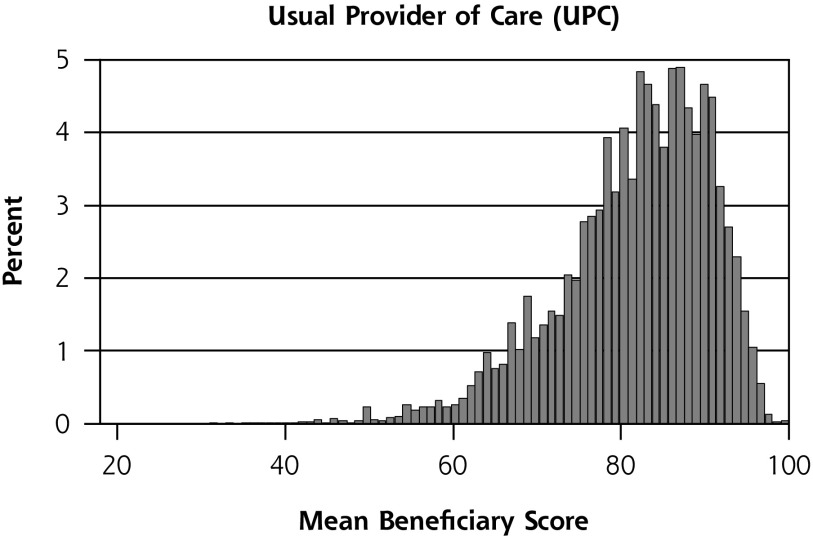

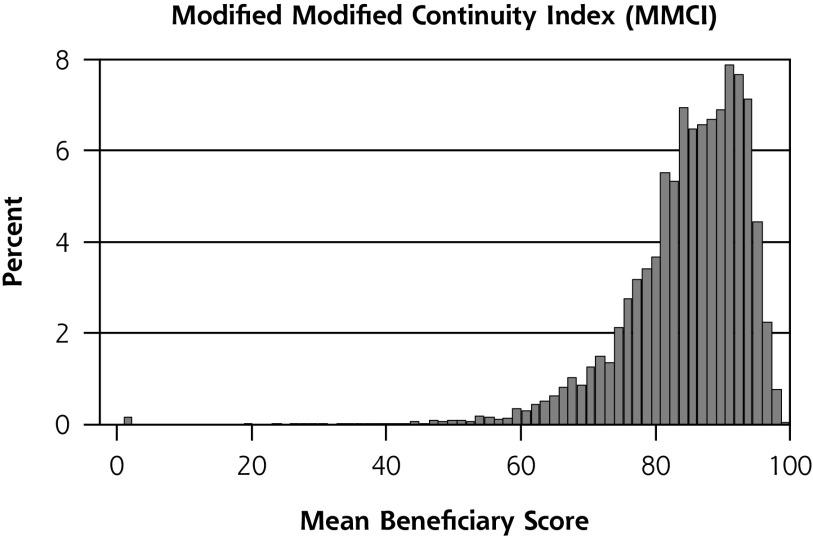

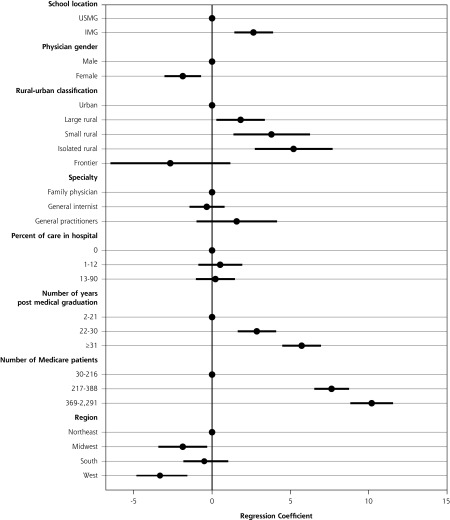

We found a strong correlation across the 4 continuity measures; correlation coefficients ranged from 0.86 to 0.99 (Supplemental Table 1, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/492/suppl/DC1/). All were approximately normally distributed, but with a negative (left) skew (Figure 1). Physicians with more years since graduation, more Medicare patients, and those practicing in rural areas were more likely to provide continuous care. Primary care physicians practicing in the West were less likely to provide continuous care (Figure 2, Supplemental Table 2 available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/492/suppl/DC1/).

Figure 1.

Distribution of physician-level continuity scores for 4 common individual measures.

Figure 2.

Physician characteristics associated with providing continuity of care (BB-COC), adjusted. (N = 6,551)

BB-COC = Bice-Boxerman continuity of care; USMG = US medical graduate; IMG = international medical graduate.

Notes: Source is 2011 Medicare Claims Data.1 Outcome is mean BB-COC score for patients receiving care from a primary care physician. See Supplemental Table 2 for regression results (Supplemental Table 2 available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/492/suppl/DC1/).

Given the tight correlations, and the National Quality Forum endorsement of the BB-COC as a quality measure for care of children with complex needs, we selected the BB-COC to illustrate our findings. Parallel results for the other 3 continuity measures are presented in Supplemental Table 3 (Supplemental Table 3 available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/492/suppl/DC1/).

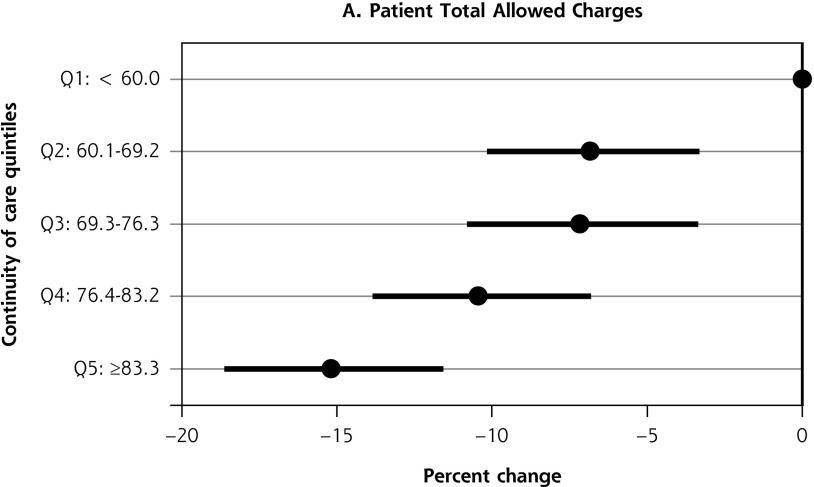

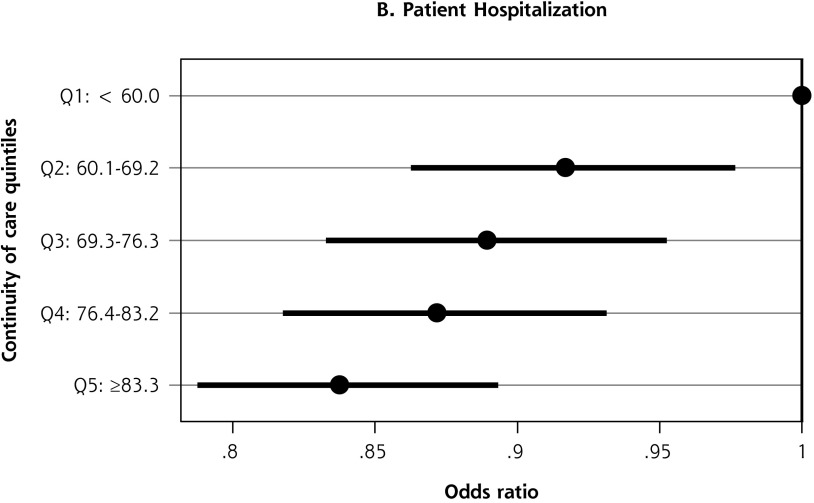

Of the 1,448,952 beneficiaries obtaining some care from the 6,551 primary care physicians in our sample, 1,178,369 (81.1%) obtained most of their care from them. Adjusted expenditures for beneficiaries cared for by physicians in the highest BB-COC quintile ($6,958) were 14.1% lower than for those in the lowest quintile ($8,092) (β = –0.151; 95% CI, –0.186 to –0.116). The odds of any hospitalization were 16.1% lower at the highest continuity quintile compared with the lowest quintile (OR = 0.839; 95% CI, 0.787 to 0.893) (Figure 3). Analyses of alternative continuity measures yielded similar results (Supplemental Table 3, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/492/suppl/DC1/). The reduction in allowed charges from highest to lowest quintiles ranged from 12.4% (MMCI) to 15.7% (UPC and HI). Similarly, the reduction in the odds of hospitalizations from the highest to lowest quintiles ranged from 15.7% (HI) to 17.1% (MMCI).

Figure 3.

Association between physician-level continuity of care (BB-COC) and outcomes.

BB-COC = Bice-Boxerman continuity of care; Q = quintile.

Notes: Source is 2011 Medicare Claims Data.1 Outcomes are (1) the natural log of allowed patient charges, and (2) whether or not the beneficiary was hospitalized in in 2011. Multilevel analysis of 1,178,369 beneficiaries and 6,551 primary care physicians. Models include controls for physician and patient characteristics (see Supplemental Table 3, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/492/suppl/DC1/).

DISCUSSION

We found a strong association between higher levels of physician-level continuity, a core tenet of primary care, and lower total health care costs and hospitalizations. These findings support international findings19 and previous analysis of Medicare beneficiaries with specific chronic diseases,20 but with a much larger and more generalizable sample. The value associated with a 14% reduction in costs is roughly $1,000/beneficiary/year. Higher continuity, measured at the patient level using BB-COC, was recently shown to be significantly associated with reduction in emergency care for elderly patients in England,21 and a recent systematic review found significant, positive association between continuity and reduced mortality.22 Continuity is already endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a quality measure for children with complex care needs, and these findings suggest that continuity may be useful as a physician-level measure for quality and/or resource use under the QPP. The BB-COC continuity index is provisionally approved as a Qualified Clinical Data Registry measure for QPP for participants in the PRIME Registry but it remains unclear what additional information the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will require to accept it for wider use. High-value primary care measures, including continuity and comprehensiveness, might simultaneously serve as metrics of both quality and resource use, given their now demonstrated relationship to substantial cost/utilization reductions.23

Primary care has the largest number of QPP measures but most of these are intermediate, disease- focused, and process measures, which risk driving primary care focus away from its core functions and real value. When tied to strong extrinsic motivation, namely payment, these measures threaten a continued erosion of primary care’s commitment to care continuity. Perhaps related, national health surveys suggest a decline in people identifying a usual source of care.21,24 There is a strong, national effort to move Medicare providers into value-based payment, including the federal QPP, and the alignment of such payment with high-value primary care functions would logically be a priority.

Our research has limitations, and further work is needed to understand how continuity measurement might impact provider behavior. Whether these continuity outcomes hold for populations other than Medicare beneficiaries cannot be inferred from our study, nor can we comment on whether and how associations would change over a study period longer than a single year. Several of the cited studies,3,4,5,19,20 however, do suggest that the associated benefits are not age dependent, and it is likely that continuity over a longer period would convey even greater protection from undesirable outcomes.

In summary, this study contributes to the overwhelming evidence of the value of continuity care5,7,8,11-13,21,22,25,26 and offers 1 or more quality measures that could be used and prioritized in the QPP or other value-based payment models. Continuity is 1 of a handful of core tenets of primary care that should be incorporated into official primary care measures as we shift from paying for services to paying for value. Future studies should investigate the relative effects of provider vs team and practice continuity, continuity across settings (eg, inpatient to outpatient), and further refine calculations of continuity to capture effects of longitudinal continuity. Research is also urgently needed to produce reliable measures of other core primary care tenets such as comprehensiveness and coordination.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/16/6/492.

Previous presentations: Portions of the findings reported have been presented at the NAPCRG Annual Meeting; November 12-16, 2016; Colorado Springs, Colorado, and the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting; June 25-27,2017; New Orleans, Louisiana.

Supplementary materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/16/6/492/suppl/DC1/.

Funding support: The Robert Graham Center received support for this study from the American Board of Family Medicine Foundation in the form of a contract for ongoing collaborative research.

References

- 1.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005; 83(3): 457-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson M, Yordy K, Lohr K, Vaneslow N. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1996. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=5152&page=R1 Accessed Apr 16, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):445-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):159-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McWhinney IR. Continuity of care in family practice. Part 2: implications of continuity. J Fam Pract. 1975; 2(5): 373-374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peabody F. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88(12):877-882. http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/245777. Published Mar 19, 1927 Accessed Jan 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernandez-Boussard T, Bentler SE, Morgan RO, Virnig BA, Wolinsky FD. The association of longitudinal and interpersonal continuity of care with emergency department use, hospitalization, and mortality among medicare beneficiaries. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9(12): e115088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentler SE, Morgan RO, Virnig BA, Wolinsky FD. Do claims-based continuity of care measures reflect the patient perspective? Med Care Res Rev. 2014; 71(2): 156-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack CE, Hussey PS, Rudin RS, Fox DS, Lai J, Schneider EC. Measuring care continuity: a comparison of claims-based methods. Med Care. 2016; 54(5): e30-e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breslau N, Haug MR. Service delivery structure and continuity of care: a case study of a pediatric practice in process of reorganization. J Health Soc Behav. 1976; 17(4): 339-352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care. 1977; 15(4): 347-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magill MK, Senf J. A new method for measuring continuity of care in family practice residencies. J Fam Pract. 1987; 24(2): 165-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smedby O, Eklund G, Eriksson EA, Smedby B. Measures of continuity of care. A register-based correlation study. Med Care. 1986; 24(6): 511-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356(11): 1130-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo Y-F, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(11): 1102-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40(5): 373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richard Morrill JC. Metropolitan, urban, and rural commuting areas: toward a better depiction of the United States settlement system. J Urb Geo. 1999; 20(8): 727-748. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Maeseneer JM, De Prins L, Gosset C, Heyerick J. Provider continuity in family medicine: does it make a difference for total health care costs? Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(3):144-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussey PS, Schneider EC, Rudin RS, Fox DS, Lai J, Pollack CE. Continuity and the costs of care for chronic disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2014; 174(5): 742-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tammes P, Purdy S, Salisbury C, MacKichan F, Lasserson D, Morris RW. Continuity of primary care and emergency hospital admissions among older patients in England. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(6):515-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira Gray DJ, Sidaway-Lee K, White E, Thorne A, Evans PH. Continuity of care with doctors-a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open. 2018; 8(6): e021161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL., Jr More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):206-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liaw W, Jetty A, Petterson S, Bazemore A, Green L. Trends in the types of usual sources of care: a shift from people to places or nothing at all [published online ahead of print on August 31, 2017]. Health Serv Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler R, Vasiliadis A, Bickell N. The relationship between continuity and patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2010; 27(2): 171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003; 327(7425): 1219-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]