Abstract

PURPOSE

Up to one-third of female smokers with Medicaid deny tobacco use during pregnancy. Point-of-care urine tests for cotinine, a tobacco metabolite, can help to identify women who may benefit from cessation counseling. We sought to evaluate patient and clinician perspectives about using such tests during prenatal care to identify smokers, with particular focus on the impact of testing on clinical relationships and the potential for tobacco cessation.

METHODS

We conducted 19 individual interviews and 4 focus groups with 40 pregnant or postpartum women covered by Medicaid who smoked before or during pregnancy. Patients also took the urine cotinine test and received sample results. Interviews were conducted with 20 health care practitioners. We analyzed the transcripts using an inductive approach and developed a model of how prenatal testing for cotinine could affect the patient-clinician relationship.

RESULTS

Patients were more likely than clinicians to believe that testing could encourage discussions on tobacco cessation but emphasized that the clinician’s approach to testing was critical. Clinicians feared that testing would negatively affect relationships.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite having reservations, low-income patients had a surprisingly favorable view of using point-of-care urine testing to promote smoking cessation during pregnancy, which could increase the availability of cessation resources to women who do not disclose their tobacco use to clinicians.

Key words: smoking, pregnancy, qualitative research, cotinine, tobacco cessation, prenatal care, vulnerable populations, physician-patient relations, primary care, practice-based research

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use during pregnancy is widely cited as the most important preventable cause of negative birth outcomes.1-6 Approximately 10% of all women smoke while pregnant.7 Studies show that there are high rates of nondisclosure during pregnancy, as 30% of women with Medicaid insurance who smoke fail to reveal this behavior to their clinicians, with estimates among other groups of women ranging from 13% to 39%.2,6,8-12 Women are more likely to attempt smoking cessation while pregnant, but those who do not disclose their tobacco use are unlikely to receive recommended and effective tobacco cessation counseling.1,4,6,13,14 The reasons for this lack of disclosure remain unclear, but may be due to increased public awareness of tobacco’s harmful effects during pregnancy.6,9,15,16

Point-of-care screenings and counseling for behaviors such as alcohol use and domestic violence are common in prenatal care and accepted by clinicians.17 Over the past several decades, tests for cotinine and other tobacco byproducts have become available and are used in research settings to identify pregnant smokers. When combined with standard counseling, testing has resulted in increased cessation18 and higher birth weights.19 Urine testing for cotinine may be useful in reducing nondisclosure surrounding prenatal tobacco use, though currently, it is not used routinely in the clinical setting.2,18,19

It is unknown how women would react to such a test used as a part of routine prenatal care and whether this testing would affect their relation ship with and trust in their clinicians.18,20 We sought to examine women’s thoughts on how urine dipstick testing would affect the clinical relationship and hoped to clarify barriers to disclosure as well as how these might be eliminated. We also aimed to explore how testing might affect nondisclosure and to determine whether it would be a useful addition to standard prenatal care in an effort to increase tobacco cessation.

METHODS

This analysis is one part of a larger study to assess patient and clinician reactions to use of urine cotinine testing for tobacco detection in prenatal care. Eligible women were pregnant or no more than 6 months postpartum, self-reported tobacco use during or shortly before pregnancy, and had Medicaid insurance. We recruited participants from 2 clinics affiliated with a large academic medical center, both with a high percentage of Medicaid patients. All provided written informed consent.

Prospective participants were informed of the purpose of the study and that we would test their urine for a tobacco byproduct as a part of the study. Women participated in either a semistructured interview (n = 19) or a focus group (n = 21). Both modalities sought to identify patient views on tobacco use in pregnancy and testing for use, and opinions about how a test would affect a patient’s relationship with her clinician (Supplemental Appendix 1, http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/507/suppl/DC1). We were deliberate in using both interviews and focus groups as we suspected that women would be more comfortable sharing some information in one setting and not the other. We gathered quantitative data including demographics, a brief smoking history, a summary of potential tobacco exposures, and pregnancy data with a paper questionnaire.

We collected patient urine samples for cotinine testing using the NicAlert test strip system (Nymox Pharmaceutical Corporation), which provides semi-quantitative detection of cotinine, a major nicotine byproduct. During the interviews or groups, patients were provided with a paper form noting whether the test identified them as a smoker or nonsmoker and the numerical cotinine result marked on a scale. All participants received written information on tobacco cessation, which advised against smoking in pregnancy.

We also conducted semistructured interviews with 20 clinicians who provide prenatal care at our institution. Participants included individuals providing obstetrical care (physicians, midwives, nurses, medical assistants). Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We met with the focus group facilitator after each session to review themes, topics, and dynamics of the meeting.

We primarily used inductive content analysis to organize and analyze the results.21,22 Analysis was started after several transcripts were obtained. Transcripts were compared to audiorecordings for accuracy and to identify general themes. This early analysis allowed researchers to get a general sense of each interview in preparation for a more detailed analysis.22-24 Preliminary codes were identified through group discussion, recorded in a code book, and edited in an iterative process as coding progressed.23,24 Each transcript was coded by 3 members of the study team (A.B.S., A.F.W., M.E.B.) using Dedoose qualitative data software (http://www.dedoose.com).25 Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached for all codes. We identified broad themes, reviewed the data to verify themes, organized them into categories, and built a model to describe our findings.21,24 Standard cross-tabulation analysis was used to summarize quantitative demographic information and tobacco history.

RESULTS

Patient Sociodemographics

Forty women, aged 18 to 37 years, participated in the focus groups and individual interviews (Table 1). About 80% had at least a high school diploma, 73% were black, and 58% were currently pregnant. The women had an average gravida of 3 and parity of 2. About two-thirds reported smoking during the current or most recent pregnancy. There were no significant differences in demographics or smoking status between focus group and interview participants (Supplemental Appendix 2, http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/6/507/suppl/DC1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Patients (N = 40)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) [range], y | 26 (5) [18-37] |

| Race, No. (%) | |

| White | 8 (20) |

| Black | 29 (73) |

| Other | 3 (7) |

| Highest level of education, No. (%) | |

| ≤8th grade | 1 (2) |

| Some high school | 7 (18) |

| High school diploma/GED | 12 (30) |

| Some college, no degree | 17 (43) |

| Associates degree | 3 (7) |

| Pregnancy history | |

| Number of pregnancies, mean (SD) | 3 (2.6) |

| Parity, mean (SD) | 2 (1.7) |

| Currently pregnant, No. (%) | 23 (58) |

| Smoking status during this pregnancy, | |

| No. (%) | |

| Smoked | 27 (68) |

| Did not smoke | 7 (17) |

| Not reported | 6 (15) |

| Tobacco smoke exposure, No. (%) | |

| Lives with a smoker | 19 (48) |

| Partner is a smoker | 26 (65) |

| Works with smokers | 12 (30) |

GED = general equivalency diploma.

Overview

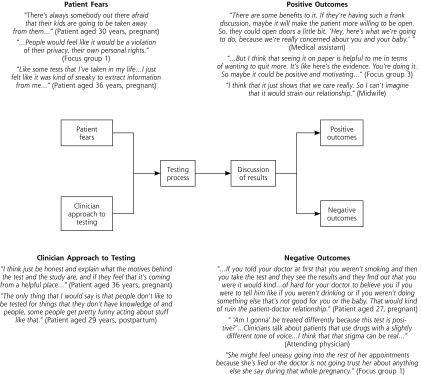

Although the majority of women interviewed voiced a belief that testing for tobacco use in pregnancy would be a good idea, they also expressed reservations, fearing a negative impact on patients’ relationship with clinicians (Table 2). Women specifically had fears about the testing process and believed that a patient’s reaction would depend on how physicians and midwives framed and explained the test, as well as how positive test results were presented to patients. We used these data to develop a model illustrating the potential impact of testing on relationships between patients and clinicians (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Patient and Clinician Views on Testing Extracted From Qualitative Interviews

| Themea | Description | Quotation (Source) |

|---|---|---|

| Testing is generally a good idea | Large majority (89%) of patients believed that testing women for smoking during pregnancy would be positive for women and their pregnancies. It is important to note that these statements were not mutually exclusive from concerns about testing and the impact it would have on their relationship with clinicians. | “I think these tests, like the urine tests and the drug tests, is good for the mothers just so that the doctors will know and try to get treatment and help for the mothers.” (Focus group 4) “Why do I think it’s a good way to check? … I’m thinking of it just in terms of helping other women just to keep that positive reinforcement going.” (Patient aged 37 years, Postpartum) |

| Testing would increase disclosure | Most patients believed that testing women for tobacco use would increase the number who disclosed their smoking status to clinicians and help women in making this disclosure. | “I’d try to tell them before it [the test] come back. ‘Look, I did want to tell you, but I know these results are going to come back, so I might as well go ahead and tell you that I smoke 3 cigarettes a day. You know it was 10, but now it’s 3. I’m trying to cut back. So if you can give me any options or resources that can help me go ahead and quit, let’s go ahead and get down to the nitty gritty.’ That’s how it would be.” (Focus group 2) “… with seeing the results and doing the test that would motivate me to be like okay, maybe I should just go ahead and tell my doctor the truth and let him know what’s going on so we can just stop it right there.” (Patient aged 27 years, pregnant) |

| Testing may have some negative effect on relationship | Although only one-third of women expressed that testing would have negatively affect their relationship with clinicians, more than 80% of clinicians expressed this view. In general, clinicians expressed more concern about patient privacy and the potential punitive nature of the test. | “If you come out telling the truth, then you and your doctor have a good relationship, but if they feel like you’re a liar and you prove that you’re a liar, then your doctor will probably feel different, maybe become impatient because they always think that you’re lying.” (Patient aged 18 years, pregnant) “I’d worry about it. It’s the same thing with the uTox screens. You have the potential to really ruin that relationship…” (Attending physician) “… a patient will get angry if they have a false-positive for a test they don’t believe they deserve and a cynical provider might say, ‘You should believe the test and not the patient.’ …” (Attending physician) |

| Testing will increase cessation | The majority (81%) of women expressed the view that testing for tobacco use would increase smoking cessation. | “It’s a good way because like I said, if they want to stop smoking, then this test will actually help them out, but if they already know that they’re smoking and they’re not willing to try and stop, there’s no need.” (Patient aged 18 years, pregnant) |

| Testing will have no effect on cessation | – | “Because if your mind already set on doing something, you are going to set your mind on that and you are going to do what you want to do.” (Focus group 1) “Some people just need more assistance to stop. So that [the test] just might open up the doors a little bit more for that extra help that they need to stop smoking.” (Patient aged 27 years, pregnant) |

uTox = urine toxicology.

Themes listed are a selection from those developed as described in Methods.

Figure 1.

Descriptive model of how prenatal urine cotinine testing could affect the patient-clinician relationship, both positively and negatively.

Specific Themes

Several themes emerged from the interview and focus group discussions. These themes are described below with exemplifying quotations from participants.

Urine Testing Can Be Helpful in Tobacco Cessation

More than two-thirds of the patient participants believed that urine testing for tobacco during prenatal care could be beneficial in helping women to quit smoking (Table 2). One woman noted that pregnancy should be a motivator to quit, and test results would reinforce this. Women described the patient’s mindset as the most important factor in whether she will quit smoking and asserted that tests would be most effective in those who were already contemplating cessation. Participants also believed that just seeing a positive result could motivate some women, however. When asked about how it felt to see their results in print during the study, one participant responded as follows:

“…it’s easy to tell someone, like, ‘Oh, smoking’s not bad,’ but once that person sees it for themselves, it’s like, ‘Okay, well maybe they’re right, or maybe I should consider doing this which is best for me.’” (Focus group 3)

Patient Fears About Testing

Patients were most concerned about how clinicians would react to positive cotinine test results in women who had reported being nonsmokers. Some worried that their privacy would be violated, while others feared the involvement of Child Protective Services (CPS) or other government officials. Focus group participants wondered if women with positive tests could be accused of neglect or child endangerment, comparing tobacco to their experiences involving illegal substances.

“…Cigarettes are legal…are you going to take my baby from me because I smoke cigarettes? No. There’s not a law that states that I can’t smoke cigarettes while I’m pregnant… You can’t take my child from me… don’t make me feel guilty because I’m smoking. I could be trying to quit…it’s hard… and you’re badgering me about stuff…” (Focus group 2)

Patients also worried that testing might adversely affect trust in the clinician. One woman explained this concern with the following statement:

“Well if they’re lying about this, what else can we believe them about?” (Focus group 2)

For some women, however, an important caveat to these fears was the idea that the health of the pregnancy is more important than these negative outcomes.

“… But if they didn’t tell me [that they were testing]…like my privacy was kind of taken away… the bottom line is… you are lying to your health professional and if there are steps and measures that we can take to help your baby beforehand, I think that that’s more important.” (Patient aged 27 years, pregnant)

Clinician’s Approach to Testing Is Important in Maintaining a Positive Relationship

Patients reported they would be more open to testing if physicians and midwives described how the test could be helpful to women and their pregnancies. Some commented that test results should not affect the patient-clinician relationship, regardless of whether the patient is forthcoming (Table 3). The majority of patients interviewed reported an expectation that their clinicians would be helpful. They believed that this helpful attitude should motivate women to be honest about their own behaviors, allowing them the opportunity to receive help with cessation.

“So I think that honesty with yourself is really important… and then you can express that to your doctor and your doctor can actually help you.” (Patient aged 36 years old, pregnant)

Table 3.

Patient Recommendations for Maintaining Trust in the Patient-Clinician Relationship With Cotinine Testing

| Recommendation | Quotation (Source) |

|---|---|

| Clinicians should acknowledge that patients expect them to be helpful | “I mean, I don’t think it should affect the relationship because if anything the doctor is there to help and the patient is there to be seen.” (Patient aged 25 years, pregnant) “It shouldn’t really affect their relationship. The doctor’s going to offer about quitting and everything. Stand by the patient. Keep encouraging the patient. So it shouldn’t affect the relationship.” (Patient aged 33 years, postpartum) |

| Clinicians must obtain consent before testing | “Like, if the doctor doesn’t bring it up and then just puts the test on the unsuspecting woman, then that would create a trust issue with her and then she’s not going to be able to open up to the doctor…” (Patient aged 36 years, pregnant) |

| Clinicians should explain how testing can be helpful for the pregnancy | “I mean I think that depending on how you frame it, it may or may not affect the relationship. If you make it so it’s like, ‘You know, you say you don’t smoke, but I’m going to make you take this test anyway because I don’t believe you,’ if you frame it like that, it’s going to damage the relationship. If you say, ‘We’re testing everybody for this so we can find out if we need to intervene and provide tips,’ I think people would be more receptive to it and not diminish the relationship.” (Resident physician) |

| Clinicians should avoid judgment of patient behaviors | “I think just because maybe the doctor might look down on you, like you don’t care about your baby…” (Patient aged 27 years, pregnant) “I really try to get them to be honest with us about what’s going on and I really try to make it nonjudgmental. This feels very judgmental. This feels like the opposite of what I try to do, and I think people, you know, if you present it in a nonjudgmental way, will tell you, ‘I’m smoking a half a pack, I’m smoking a pack.’ I just wish we could go at it more from an angle of trying to figure out how to help people with their stress during pregnancy because I think people want to do right by their kids and I think people want to stop smoking or cut down.” (Nurse) |

Although the study team never suggested or encouraged cotinine testing done in secret, both patients and clinicians raised patient consent to testing as a serious concern (Table 3). Participants noted that any testing done without consent would lead to a sense of being deceived and mistrust of the health care system. Some worried that women might avoid prenatal care entirely given the risk of a positive test or the fear of being nagged about their smoking (Figure 1).

Clinicians Fear Testing Will Harm Relationships

Clinicians were much more skeptical and concerned that urine testing would negatively affect their relationship with patients. They believed the test could “breach” their patients’ trust in them and questioned whether results would affect their clinical management.

“… The number of patients that you’re going to ‘catch smoking’ who aren’t [disclosing their smoking status] is probably going to be very few, so it’s a very expensive test…My management during the pregnancy doesn’t change whether they’re a smoker or not…” (Obstetrical fellow)

Comparisons were made to urine toxicology screenings and the stigma pregnant women with substance dependence face from health care professionals. Clinicians asserted that women should not have to “prove that they are telling the truth.” They expressed a desire to be partners with their patients rather than being punitive or paternalistic.

“I would worry about how it would be used, and I don’t want to punish women for smoking. I want to educate them and teach them and tell them it’s not good for their baby or for them.” (Midwife)

Differences in Data From Focus Groups vs Individual Interviews

Focus group participants were more suspicious of clinicians’ motives, although across the board, women still generally viewed the test itself as valuable in tobacco cessation. Women asserted that clinicians should not be concerned about using tobacco as it is legal and less harmful than other substances. Concerns about CPS were brought up in all focus groups, but in only 4 interviews. Women believed that regardless of consent, smoking status is “none of their [clinicians’] business” and expressed autonomy over their bodies and their children. Participants worried about being controlled and believed that compelling women to disclose tobacco use would be itself a breach of confidentiality.

“Because I am telling you one thing…you are trying to act like a police officer and really figure out what if I am telling you, is it true or not…I am telling you this out of my mouth so you don’t believe me so you trying to go investigate some other stuff that really don’t concern you.” (Focus group 1)

Interestingly, these criticisms of testing seem to directly contradict the sentiment that clinicians will be supportive and helpful, which was also raised in all focus groups.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated patient acceptance of cotinine screening during prenatal care, which has considerable implications for reducing tobacco use during pregnancy. Testing for cotinine and other tobacco byproducts has been available for decades, but typically required access to specialized equipment. Urine dipstick testing offers more accessible and affordable testing. Although rapid point-of-care tests for cotinine are primarily used in research settings, testing of pregnant smokers in conjunction with standard counseling has resulted not only in increased cessation but also in improvements in newborn birth weight.18,19

Women reported strong acceptance of using a urine test for smoking detection during prenatal care, consistent with earlier findings that women are comfortable with prenatal screening for other substances.26-28 They believed that this screening could be a valuable tool in tobacco cessation by reinforcing an existing desire to quit and encouraging those who had not considered it. Additionally, women stated that the test could actually strengthen the relationship with their clinicians, particularly if clinicians provided information, resources, and support in cessation efforts. That being said, women also described important reservations about the testing process.

The most striking patient findings were concerns about violation of privacy and the involvement of the legal system or CPS. Smoking during pregnancy does not necessitate such involvement, but this fear was articulated in all focus groups. Prior literature has noted that the fear of CPS involvement is a barrier to prenatal care for women who have substance abuse dis orders.26,29 It would be worrisome if tobacco testing in pregnancy led women to avoid prenatal care because of either concern for legal consequences or stigma and judgment from clinicians.27,30 Whether this trend would also hold true for cotinine testing is unknown and warrants further investigation.

Clinicians were much less likely to view the test as helpful in promoting cessation and believed that a positive cotinine test would not influence a woman’s desire to quit unless she was already motivated. They explained that knowledge of patient tobacco use would not change their management and minimized the impact of tobacco use during pregnancy. This view is surprising and concerning given the well-documented risks of tobacco use during pregnancy.1-4,6 Cessation counseling has been shown to be particularly effective during pregnancy, and can result in a 30% to 70% improvement in cessation rate if women are screened and counseled as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.2,4,6,8,31

Patient and clinician fears around prenatal cotinine testing can be combatted in a variety of ways (Table 3). First, clinicians should be educated to reemphasize the risks of tobacco use during pregnancy and the increased effectiveness of cessation counseling during this time. Clinicians can counsel patients on the potential risks and adverse effects, which can help in the management of expectations. This study provides important information on patient’s views, which can be shared with clinicians to allay fears of disrupting their relationships with patients. In the same vein, patients should be educated on the true effects of tobacco in pregnancy as we found that some women viewed use as less harmful given its legality.

Like all studies, ours has limitations. This study focused specifically on patients with Medicaid insurance, as prior literature showed that this group is at high risk for smoking nondisclosure, but it therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. We collected standard demographic information from patients, but did not do the same for clinicians. We feared that doing so would compromise participant privacy and potentially inhibit ease in speaking candidly, as the pool of eligible clinicians was relatively small. In addition, individual interview patients may have censored their responses or tried to give socially acceptable answers if they viewed study team members as a part of the medical establishment. Although patients and clinicians were recruited from the same clinics, patients were not aware of this fact, so we do not believe that patient responses were influenced by fear that their personal clinicians might learn their results.

One limitation of our methodology was the establishment of a finite number of interviews because of timing and funding constraints. We recognize that ideally, we would have scheduled interviews until we reached theme saturation. Despite this shortcoming, we are comfortable with the number of interviews conducted as we failed to elicit any new themes as we approached the end of the interview process. We also recognize that it is not typical to analyze focus group and interview data collectively, but we decided that this approach would provide different types of information given the social stigma of smoking during pregnancy and the potential for increased comfort in discussing this topic with other smokers. Focus groups can move in a variety of directions based on participant responses,31 providing a broad range of views to augment the individual interviews, which were more structured. We believe that this approach is one of the strengths of the study as it allowed us to try to understand the complex relationships around cotinine testing.

The patient participants in this study provide important insight on how the testing process can be optimized to ensure strong relationships and high-quality patient care. It is essential to provide informed consent, detailing information about the use of test outcomes to help encourage healthy behaviors and good birth outcomes, clarifying that the tests help clinicians know when to talk about tobacco use with patients, and clearly explaining that a positive test will not result in a report to authorities. This study can help to emphasize to clinicians that their actions, behavior, caring, and support may be far more important in maintaining trust in their relationship with patients than the test results themselves.14,32

Although our study found that patients were generally in support of urine cotinine testing to aid tobacco cessation, it also identified patient and clinician fears and potential unforeseen consequences from testing. Identification of these concerns allows health systems that introduce cotinine testing to proactively acknowledge and address potential barriers to its use. With 13% to 39% of pregnant smokers not reporting tobacco use to clinicians, many such women may never be counseled about the importance of cessation or provided with tools to quit. As tobacco cessation counseling has been shown to be cost-effective and efficacious, there could be enormous public health benefits to introducing this test as a part of routine prenatal care. Future work should assess the feasibility of introducing this testing in the clinical setting. We believe that despite negative perceived effects by clinicians, urine cotinine testing can serve as a practical way to identify affected women and to provide them with appropriate care.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/16/6/507.

Prior presentations: Poster presentations were made at the 2015 Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting; February 25-28, 2015; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and the 2015 Congress on Women’s Health; April 16-19, 2015; Washington, DC. The abstract was published in the March 2015 edition of the Journal of Women’s Health.

Supplemental Materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/16/6/507/suppl/DC1/.

Author contributions: Authors A.A.B-S., M.E.B., and K.G. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: K.G., M.E.B. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: A.A.B-S., K.G. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Obtained funding: K.G. Study supervision: K.G, M.E.B.

Funding support: This research was supported by a grant from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation.

Disclaimer: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, et al. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2015(12): CD010078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell T, Crawford M, Woodby L. Measurements for active cigarette smoke exposure in prevalence and cessation studies: why simply asking pregnant women isn’t enough. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004; 6(Suppl 2): S141-S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michigan Department of Community Health. Michigan’s State Health Assessment and State Health Improvement Plan (SHIP) 2012-2017. https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/MDCH_SHIP_FINAL_8-16-12_400674_7.pdf Accessed Nov 15, 2017.

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 471: Smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116(5): 1241-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; 8(3): CD001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orleans CT, Barker DC, Kaufman NJ, Marx JF. Helping pregnant smokers quit: meeting the challenge in the next decade. Tob Control. 2000; 9(Suppl 3): III6-III11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Reproductive Health Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). CDC PRAMStat Data for 2011. https://chronicdata.cdc.gov/Maternal-Child-Health/CDC-PRAMStat-Data-for-2011/ese6-rqpq/data Accessed Nov 15, 2017.

- 8.Windsor RA, Lowe JB, Perkins LL, et al. Health education for pregnant smokers: its behavioral impact and cost benefit. Am J Public Health. 1993; 83(2): 201-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britton GRA, Brinthaupt J, Stehle JM, James GD. Comparison of self-reported smoking and urinary cotinine levels in a rural pregnant population. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004; 33(3): 306-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz PM, Homa D, England LJ, et al. Estimates of nondisclosure of cigarette smoking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 173(3): 355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swamy GK, Reddick KL, Brouwer RJ, Pollak KI, Myers ER. Smoking prevalence in early pregnancy: comparison of self-report and anonymous urine cotinine testing. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011; 24(1): 86-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shipton D, Tappin DM, Vadiveloo T, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Chalmers J. Reliability of self reported smoking status by pregnant women for estimating smoking prevalence: a retrospective, cross sectional study. BMJ. 2009; 339: b4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sexton M, Hebel JR. A clinical trial of change in maternal smoking and its effect on birth weight. JAMA. 1984; 251(7): 911-915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; (10): CD001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuber J, Galea S. Who conceals their smoking status from their health care provider? Nicotine Tob Res. 2009; 11(3): 303-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb DA, Boyd NR, Messina D, Windsor RA. The discrepancy between self-reported smoking status and urine cotinine levels among women enrolled in prenatal care at four publicly funded clinical sites. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003; 9(4): 322-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor P, Zaichkin J, Pilkey D, Leconte J, Johnson BK, Peterson AC. Prenatal screening for substance use and violence: findings from physician focus groups. Matern Child Health J. 2007; 11(3): 241-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cope GF, Nayyar P, Holder R. Feedback from a point-of-care test for nicotine intake to reduce smoking during pregnancy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2003; 40(Pt 6): 674-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddow JE, Knight GJ, Kloza EM, Palomaki GE, Wald NJ. Cotinine-assisted intervention in pregnancy to reduce smoking and low birthweight delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991; 98(9): 859-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelms E, Wang L, Pennell M, et al. Trust in physicians among rural Medicaid-enrolled smokers. J Rural Health. 2014; 30(2): 214-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 62(1): 107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M. Qualitative analysis: what it is and how to begin. Res Nurs Health. 1995; 18(4): 371-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007; 42(4): 1758-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dedoose Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. Los Angeles, CA: Socio-Cultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts SC, Nuru-Jeter A. Women’s perspectives on screening for alcohol and drug use in prenatal care. Womens Health Issues. 2010; 20(3): 193-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byatt N, Biebel K, Friedman L, Debordes-Jackson G, Ziedonis D, Pbert L. Patient’s views on depression care in obstetric settings: how do they compare to the views of perinatal health care professionals? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013; 35(6): 598-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seib CA, Daglish M, Heath R, Booker C, Reid C, Fraser J. Screening for alcohol and drug use in pregnancy. Midwifery. 2012; 28(6): 760-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howell EM, Heiser N, Harrington M. A review of recent findings on substance abuse treatment for pregnant women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999; 16(3): 195-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone R. Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health Justice. 2015; 3(1): 1-15. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan TR, Dake JR, Price JH. Best practices for smoking cessation in pregnancy: do obstetrician/gynecologists use them in practice? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006; 15(4): 400-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thom DH, Hall MA, Pawlson LG. Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004; 23(4): 124-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]