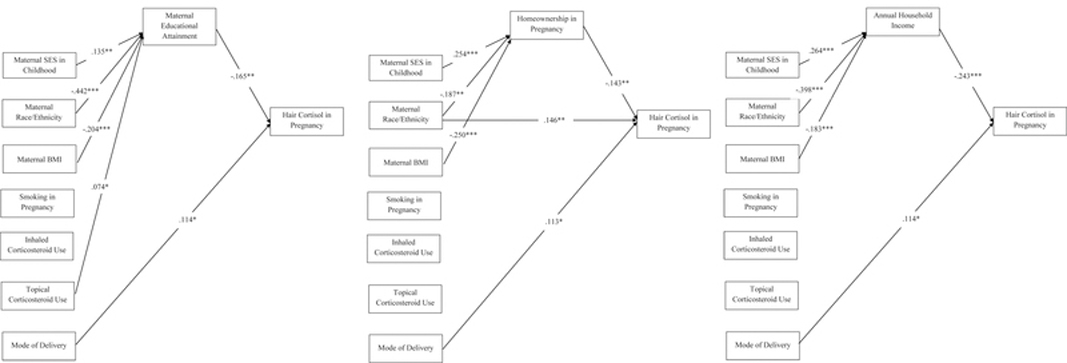

Figure 1.

Models testing contributions of maternal socioeconomic status (SES) in childhood and in pregnancy on maternal hair cortisol levels during pregnancy. Maternal SES in childhood was operationalized as the number of developmental periods (early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence) during which the mother’s parents owned their home. Maternal hair cortisol in pregnancy was operationalized as hair cortisol level during the third trimester, log-transformed to reduce skewness. Independent models tested three indicators of maternal SES in pregnancy: maternal educational attainment (Figure 1a), current homeownership (Figure 1b), and annual household income (Figure 1c). For all models, covariates (maternal race/ethnicity, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking during pregnancy, use of inhaled corticosteroids, use of topical corticosteroids, mode of delivery) were modeled as exerting direct effects on maternal hair cortisol in pregnancy and indirect effects through maternal SES indicators in pregnancy. For all models, only significant paths are displayed (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). The presence of a significant path from maternal SES in pregnancy to maternal hair cortisol in pregnancy in conjunction with the lack of a significant path from maternal SES in childhood to maternal hair cortisol in pregnancy indicates full mediation by the maternal SES indicator in pregnancy.