Abstract

Benzodiazepines facilitate the inhibitory actions of GABA by binding to γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs), GABA-gated chloride/bicarbonate channels, which are the key mediators of transmission at inhibitory synapses in the brain. This activity underpins potent anxiolytic, anticonvulsant and hypnotic effects of benzodiazepines in patients. However, extended benzodiazepine treatments lead to development of tolerance, a process which, despite its important therapeutic implications, remains poorly characterised. Here we report that prolonged exposure to diazepam, the most widely used benzodiazepine in clinic, leads to a gradual disruption of neuronal inhibitory GABAergic synapses. The loss of synapses and the preceding, time- and dose-dependent decrease in surface levels of GABAARs, mediated by dynamin-dependent internalisation, were blocked by Ro 15-1788, a competitive benzodiazepine antagonist, and bicuculline, a competitive GABA antagonist, indicating that prolonged enhancement of GABAAR activity by diazepam is integral to the underlying molecular mechanism. Characterisation of this mechanism has revealed a metabotropic-type signalling downstream of GABAARs, involving mobilisation of Ca2+ from the intracellular stores and activation of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin, which, in turn, dephosphorylates GABAARs and promotes their endocytosis, leading to disassembly of inhibitory synapses. Furthermore, functional coupling between GABAARs and Ca2+ stores was sensitive to phospholipase C (PLC) inhibition by U73122, and regulated by PLCδ, a PLC isoform found in direct association with GABAARs. Thus, a PLCδ/Ca2+/calcineurin signalling cascade converts the initial enhancement of GABAARs by benzodiazepines to a long-term downregulation of GABAergic synapses, this potentially underpinning the development of pharmacological and behavioural tolerance to these widely prescribed drugs.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Psychiatric disorders

Introduction

Benzodiazepines are among the most widely prescribed class of drugs worldwide. Due to their rapid anxiolytic, sedative-hypnotic, anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant effects, they are prescribed for various conditions, most prominently anxiety, insomnia and epileptic seizures [1]. Among these disorders, anxiety, often coinciding with depression, is one of the most common mental health problems in the world (World Health Organization), and is the largest cause of sickness absence in the UK [2], with ~1 in 6 adults being chronically affected according to Mental Health Foundation UK. Although benzodiazepines are very effective initially, the major limitation to their long-term use is the development of tolerance to their pharmacological effects, as well as dependence, resulting in severe withdrawal symptoms upon drug cessation [1, 3]. Nevertheless, the estimated prevalence of long-term use among patients prescribed with benzodiazepine ranges from 25 to 76%, which is equivalent to 2–7.5% of the general population [4]. Although benzodiazepines have been prescribed for over 50 years, the molecular mechanisms leading to tolerance are still poorly understood.

In the nervous system, benzodiazepines bind exclusively to the GABAARs, the main inhibitory receptors in the brain, and allosterically enhance their responsiveness to GABA [5–7]. GABAARs are GABA-gated chloride/bicarbonate channels built up as hetero-pentamers from a pool of 16 different subunits classified as α(1–6), β(1–3), γ(1–3), δ, ε, π and θ, the combination of which determines physiological and pharmacological properties, as well as the tissue and subcellular distribution of these receptors. Benzodiazepines selectively bind to γ2 subunit-containing GABAARs, which are specifically localised to GABAergic inhibitory synapses, thereby enhancing the strength of synaptic inhibition in the brain. In addition to the γ2 subunit, synaptic GABAARs incorporate two α subunits (α1, α2, α3 or α5) and two β subunits (β2 or β3), with the benzodiazepine binding site residing at the interface between the γ2 subunit and one of the α subunits [8]. In neurons, synaptic GABAARs are clustered in the vicinity of presynaptic GABA-releasing terminals, to maximise the efficacy of transmission, but they are also mobile and dynamic, being continuously trafficked between the cytoplasm and the plasma membrane and, once at the cell surface, in and out of synapses [9].

Tolerance to specific benzodiazepines develops at differing rates and degrees in patients, with sedative and hypnotic tolerance within days, and anticonvulsant and anxiolytic tolerance within weeks, as these effects are mediated by specific subtypes of synaptic GABAARs in the brain [10, 11]. Diazepam, the most widely used anxiolytic drug in the clinic, is associated with prominent side effects such as sedation, ataxia and cognitive impairments, due to its non-selective binding to and modulation of all synaptic GABAAR subtypes [1]. Believed to be an adaptation to chronic enhancement of GABAergic signalling, tolerance has been correlated to the observed uncoupling between benzodiazepines and GABA binding sites [12, 13], modifications in GABAAR subunit expression [14, 15], or changes in the level and/or signalling of other neurotransmitters [11]. Endocytosis of GABAARs has also been implicated in long-term effects of benzodiazepines, however the signalling mechanisms that regulate this process, and the effects on inhibitory synapse structure and function, remain poorly characterised [11].

We demonstrate here that prolonged treatment of neurones with diazepam leads to disruption of neuronal inhibitory GABAergic synapses as a consequence of prominent time- and dose-dependent downregulation of surface GABAARs, mediated by dynamin-dependent internalisation. In this process, prolonged activity of GABAARs triggers a metabotropic signalling pathway which involves mobilisation of intracellular Ca2+ and calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation and endocytosis of GABAARs. This, in turn, is dependent on the activity of phospholipase C (PLC), and mediated, at least in part, by diazepam-modulated direct binding of PLCδ to GABAARs. Thus, a metabotropic PLCδ/Ca2+/calcineurin signalling cascade, activated by diazepam downstream of GABAARs, leads to a long-term downregulation of GABAARs in synapses in a negative feedback fashion, a process likely to underpin the cellular correlates of pharmacological tolerance to these drugs. As such, it provides us with a new repertoire of therapeutic drug targets that may pave the way to improving the outcomes of the long-term clinical use of benzodiazepines.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Sprague–Dawley rats (UCL-BSU) were housed and sacrificed according to UK Home Office guidelines, following project approval by the UCL Ethics Committee. Primary cultures of cerebrocortical neurones were prepared as described previously [16]. Briefly, cortical tissue was dissected from embryonic day 16-17 (E16-17) rats, dissociated by trituration in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free Hepes-buffered saline solution (HBSS), and plated at the required density in serum-free neurobasal medium, on either 0.1 mg/ml poly-d-lysine-coated dishes or 0.1 mg/ml poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips or glass bottom dishes. Cultures were incubated in a humidified 37 °C/5% CO2 incubator (Heracell, Heareus, Germany), for up to 14 days prior to experimentation.

Stable α1β2-HEK293 cell line was maintained under selection with G418 disulphate (Neomycin; G5013-Sigma-Aldrich) and Zeocin (R25001-Invitrogen) [17], while a stable α1β2γ2-HEK293 cell line (Sanofi-Synthelabo, Paris, France) was maintained under selection with G418 disulphate [18].

Immunocytochemistry and synaptic cluster analysis

Cortical neurones (32,500/cm2 plated on glass coverslips) were subjected to various treatments and processed for immunolabelling using β2/3- and γ2-specific antibodies to label the cell surface GABAARs, and, following permeabilization, VGAT and MAP2-specific antibodies, to label GABAergic terminals and dendrites, respectively. Following incubation with the corresponding Alexa-Fluor secondary antibodies (Supplementary Table S1), samples were imaged using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710 Meta, Zeiss, Germany) with a ×63 oil-immersion objective.

The size and number of GABAAR clusters, and their colocalization with VGAT-terminals, were analysed using Zen2.1 software, as previously described [19]. As the imaging was done in separate channels, a threshold for each fluorophore was determined by the formula (Threshold = mean intensity + (2 × standard deviation)). GABAAR clusters were defined as immuno-reactivity greater than 0.1 μm2, with a mean fluorescence value greater than 2 × standard deviation of background fluorescence, which were present along the first 20 µm length of MAP2-positive primary dendrites. Colocalisation in separate channels (at least 50% overlap) was determined by overlaying the images. Synaptic elements size and numbers were analysed using Origin Pro 9.1 software, and the values were expressed as outlined in the figure legends. Normality tests were performed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. After normality tests were performed on each of the groups, non-parametric statistical analysis was done using Mann–Whitney test with the confidence interval of 95%, as the groups showed non-Gaussian distribution.

GABAAR internalisation assay

Cell-surface receptors were labelled in living cultured neurons or in α1β2-HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the myc-γ2 cDNA, as described previously [19]. Briefly, coverslips were incubated with ice-cold Buffer A (mM: 150 NaCl; 3 KCl; 2 MgCl2; 10 HEPES, pH 7.4; 5 Glucose), containing 0.35 M sucrose for 5 min, followed by incubation with mouse anti-β2/3 antibody (MAB341-MerckMillipore) for 30 min at 4 °C in Buffer A containing 0.35 M sucrose, 1 mM EGTA and 1% BSA. Cells were further incubated at 37 °C in Buffer A containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 5 µg/ml leupeptin, in the absence or presence of diazepam (1 µM, Tocris), for 1 h to allow internalisation of the labelled β2/3 subunit-containing GABAARs. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/4% sucrose/PBS (PFA/PBS) and processed for immunolabelling with anti-mouse Alexa-555 antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Cells were subsequently permeabilized and labelled with anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibodies (Supplementary Table S1) for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope as above.

Cell surface ELISA

Cortical neurons (14 DIV, 100,000 cells/cm2 in 24-well plates) or α1β2-HEK293 cells (111,000 cells/cm2 in 24-well plates) transiently transfected with the myc-γ2 cDNA using nucleofection (Lonza, Switzerland), were subjected to treatments with vehicle (DMSO) or diazepam (1 µM), in the absence or presence of various reagents (Supplementary Table S2). All the treatments were done in duplicate. Cells were fixed with PFA/PBS, and changes in surface and total levels of GABAARs were detected using cell surface ELISA with β2/3 (1 µg/ml)- or myc (1 µg/ml)-specific mouse monoclonal primary antibody and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody [16]. Values were expressed as mean percentage of vehicle treated control (set at 100%) ± s.e.m., with the number of independent repeats of each experiment (n) indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analysis was carried out using ANOVA with Dunnett post-hoc analysis and data plotted using OriginPro 9.1.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell recordings were made from cortical neurons (14 DIV), which were treated with DMSO or diazepam for 72 h, as described before above. Patch pipettes (resistance 8–10 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass tubing and filled with an internal solution containing (mM): 144 K-gluconate, 3 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 2 Na2-ATP, 0.2 Na2-GTP, 10 HEPES pH 7.2–7.4, 300 mOsm. Spontaneous activity of the neurons was recorded in current clamp mode (SEC 05 L/H, NPI electronics, Tamm, Germany), in the presence of TTX (1 μM), D-AP5 (50 μM) and CNQX (20 μM, all from Tocris). Synaptic potentials recorded were amplified, low-pass filtered at 2 kHz, and digitised at 5 kHz using a CED 1401 interface and data acquisition programme, Signal 4.04 (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK), and analysed offline using Signal. Single sweep amplitudes were measured from the baseline to the peak of the IPSP, and selected for analysis if greater than 0.05 mV [19]. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Student’s t test and data plotted using OriginPro 9.1.

Biochemical assays

GST pull-down assays were performed, as described previously [16] using either cortical cell lysates, GFP-PLCδ- or GFP-PRIP-transfected HEK293 cell lysates, or in vitro translated PLCδ (TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation kit, Promega). For coimmunoprecipitation analysis, primary cortical neurons or α1β2γ2-HEK293 cells transfected with GFP-PLCδ, GFP-PRIP1 or both cDNAs using Calcium–phosphate procedure [20], were incubated in the absence or presence of diazepam (1 µM), or in the absence or presence of diazepam/isoguvacine, respectively, for 2 h, and lysed under nondenaturing conditions. Cell lysates were incubated with 10 μg of either nonspecific goat IgG, or GABAAR α1-specific antibody [21], followed by incubation with Protein G-Sepharose. Precipitated proteins were resolved using SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting conducted as described previously [16], using antibodies described in Supplementary Table S3. Protein concentration was determined using either Bradford or BCA assays (ThermoFisher).

Intracellular Ca2+ imaging

Cortical neurones (14 DIV; 20,000 cells/cm2 in 35 mm glass bottom dishes) were incubated with 5 µM Fluo-4 AM/0.0025% pluronic F-127 (ThermoFisher) for 30 min at 37 °C in the Recording Buffer (in mM: 10 HEPES pH 7.35, 156 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 10 d-glucose, 2 CaCl2) containing CNQX (20 µM), TTX (0.5 µM) and D-AP5 (50 µM) [22]. Intracellular Ca2+ was recorded using Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope at 37 °C using a ×40 oil-immersion objective and recordings were analysed using Zen2.1 SP2 software (Zeiss, Germany). To quantitate changes in fluorescence intensity, the ‘Region of Interest’ tool was used to monitor regions in the somas and dendrites. The maximal fluorescence values following diazepam application were normalised to the average baseline control before the addition of diazepam (Ft/F0), and analysed using ANOVA followed by Bonferonni post hoc analysis in OriginPro 9.1 software.

Fluorescent imaging of GFP-PHPLCδ and DsRed-PRIP1

α1β2γ2-HEK293 cells (20,000 cells/cm2 in 35 mm glass bottom dish) were transfected with 0.2 μg GFP-PHPLCδ [23] in the absence or presence of 0.2 μg DsRed-PRIP1 [24] cDNA using Effectene (Qiagen) and cultured for 24 h. The cells were then incubated with Calcein Blue AM/0.0025% pluronic F-127 (ThermoFisher) for 30 min at 37 °C in HBS (in mM 10 HEPES pH7.4, 150 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 D-glucose, 2 CaCl2). Calcein Blue, GFP-PHPLCδ, or DsRed-PRIP1 emission was collected at 360–450 nm, 500–560 nm or 570–600 nm, respectively. Images (12-bit resolution) were acquired every 5 s before and after the bath application of diazepam (1 μM) and isoguvacine (5 μM) for total of 15 min using Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope at 37 °C using the ×40 oil-immersion objective and analysed using Zen2.1 SP2 software (Zeiss, Germany). Alternatively, cells were treated for 1 h with diazepam (1 μM) and isoguvacine (5 μM) in HBS (in mM: 10 HEPES pH7.4, 150 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 D-glucose, 2 CaCl2) and subsequently fixed with 4% PFA/4% sucrose (w/v). Cell surface GABAARs were labelled with an anti-β2/3 antibody (BD17) and an Alexa Fluor 555 antibody. GFP-PHPLCδ emission was collected at 500–560 nm and Alexa Fluor 555 emission was collected at 570–600 nm. To quantify changes in fluorescence, the ‘Profile’ tool was used to produce fluorescence profiles for each fluorophore. The fluorescence at the membrane (Fm) and the fluorescence in the cytoplasm (Fc), measured before and after bath application of diazepam/isoguvacine, were used to produce a fluorescence ratio Fm/Fc which was analysed using Students t-test in OriginPro9.1 software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro9.1 software. Each dataset was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For non-parametric data sets, the Kruskal–Walis test followed by Mann–Whitney test was used and the results were presented using boxplots showing the median, interquartile range, standard deviation and the mean, as specified in the figure legends. For parametric data sets, either the two-tailed Student’s t-test or ANOVA followed by Bonferonni post hoc analysis was used and the results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The exact sample size and the number of independent experiments performed, description of the samples and statistical analyses done were also specified in the figure legends. The number of timed-pregnant rats/litters was minimised by utilising the same tissue in multiple experiments, including biochemical, immunocytochemical, electrophysiological and live cell imaging experiments. Values were considered to be statistically significant for p < 0.05 (*).

Results

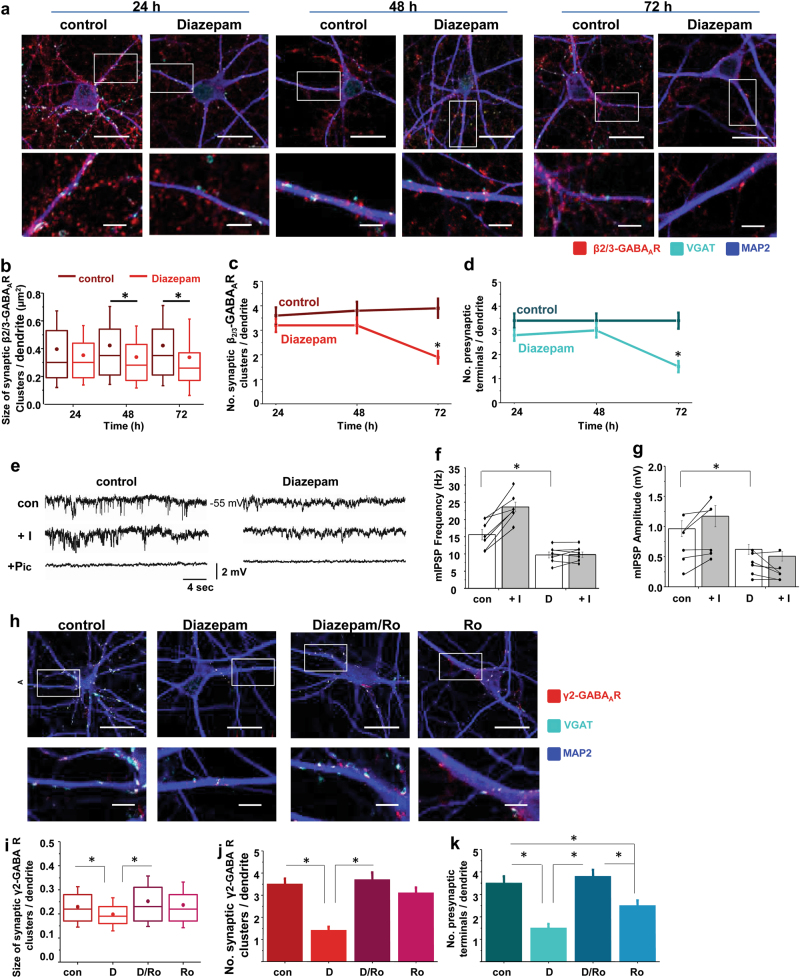

Diazepam causes a time-dependent disassembly of GABAergic synapses

Binding of diazepam to a specific allosteric site harboured by the GABAAR at the interface between α and γ subunits leads to a rapid increase in channel gating [25, 26] and results in cumulative enhancement of GABA-mediated transmission at inhibitory synapses. However, under the conditions of sustained stimulation of GABAARs by diazepam (1 μM; concentration analogous to measured plasma concentration of diazepam taken orally by patients [27]) over the time course of 72 h, inhibitory GABAergic synapses underwent a gradual decline in structural integrity due to a significant reduction in the size (Fig. 1a, b; *p < 0.05) and number of dendritic postsynaptic GABAAR clusters (Fig. 1a, c; *p < 0.05), as well as the number of colocalised GABAergic presynaptic terminals (Fig. 1a, d; *p < 0.05), as observed in triple immunolabelling experiments with GABAAR-β2/3-, vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT)- and microtubule-associated protein (MAP2)-specific antibodies and confocal imaging in primary cerebrocortical neurones. The extrasynaptic GABAAR clusters monitored at the same time, which were significantly smaller in size, but larger in number than synaptic clusters, remained unaffected by diazepam (Supplementary Figure 1a and b). The total number of immunolabelled GABAergic or glutamatergic neurones remained unchanged (data not shown). Consistent with the observed structural changes in synapses was a prominent reduction in the frequency and amplitude (Fig. 1e–g; *p < 0.05) of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (mIPSPs), recorded in whole-cell current clamp mode, in neurones treated with diazepam for 72 h. When Ro 15-1788 (flumazenil), a specific competitive antagonist at benzodiazepine binding site on the GABAAR, was applied together with diazepam, the decrease in size (Fig. 1h, i; *p < 0.05) and number (Fig. 1h, j; *p < 0.05) of postsynaptic γ2-GABAAR clusters and the decrease in the number of colocalised GABAergic terminals (Fig. 1h, k; *p < 0.05) were completely abolished, indicating that direct diazepam binding to GABAARs was necessary for the observed loss of GABAergic synapses. However, Ro 15-1788 alone caused a decrease in the number of GABAergic terminals colocalised with the postsynaptic GABAARs, suggesting that it may have additional presynaptic effects that remain to be elucidated.

Fig. 1.

Diazepam causes a time-dependent breakdown of GABAergic inhibitory synapses upon direct binding to GABAARs. a Immunolabeling of postsynaptic GABAAR β2/3-containing clusters (red) and VGAT-positive presynaptic GABAergic terminals (cyan) along MAP2-positive primary dendrites (20 µm; blue) of cortical neurons in the absence or presence of diazepam (D; 1 μM), and the corresponding graphs showing a decrease over time in b size (median/line-IQRs; mean/dot ± s.d. whiskers; Mann–Whitney test, *p < 0.05) and c number (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05) of synaptic β2/3 clusters, and d number of GABAergic terminals (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05) contacting n = 59, n = 70, n = 53 control (DMSO)-treated primary dendrites and n = 70, n = 67, n = 44 diazepam-treated primary dendrites for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively. Total of n = 17, n = 18 and n = 15 control and n = 17, n = 17 and n = 17 diazepam-treated neurons, respectively, collected from two independent experiments, were analysed in each group. e Representative traces of mIPSPs recorded in cortical neurons after 72 h treatment with control (DMSO) or diazepam (D; 1 μM), before and after application of isoguvacine ( + I, 50 μM), followed by picrotoxin ( + Pic, 50 μM; scale refers to all conditions), and corresponding bar graphs (mean ± s.d.; Student’s t-test: *p < 0.05) showing a diazepam-dependent decrease in f frequency and g amplitude of mIPSPs and the effects of isoguvacine ( + I, 50 μM; grey bars) from n = 7 control & n = 7 diazepam-treated cells collected from n = 3 independent experiments. h Immunolabelling of γ2-containing clusters (red) and VGAT-GABArgic terminals (cyan) along MAP2-positive dendrites (20 µm; blue) following 72 h treatment with control (DMSO), or diazepam (D; 1 μM), in the absence or presence of Ro 15-1788 (Ro; 25 μM), and the corresponding graphs showing a decrease in i size (median/line-IQRs; mean/dot ± s.d. whiskers; Mann–Whitney test, *p < 0.05), and j number of synaptic γ2 clusters (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05), and k decrease in the number of GABAergic terminals (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05) contacting n = 49 control-treated & n = 45, n = 53, n = 48 diazepam-, diazepam/Ro- or Ro-treated dendrites for 72 h, respectively. The total of n = 15, n = 14, n = 13, n = 16 neurons, respectively, collected from two independent experiments, were analysed in each group. Scale bars = 20 μm (a, h-upper row) and = 5 μm (a, h-lower row)

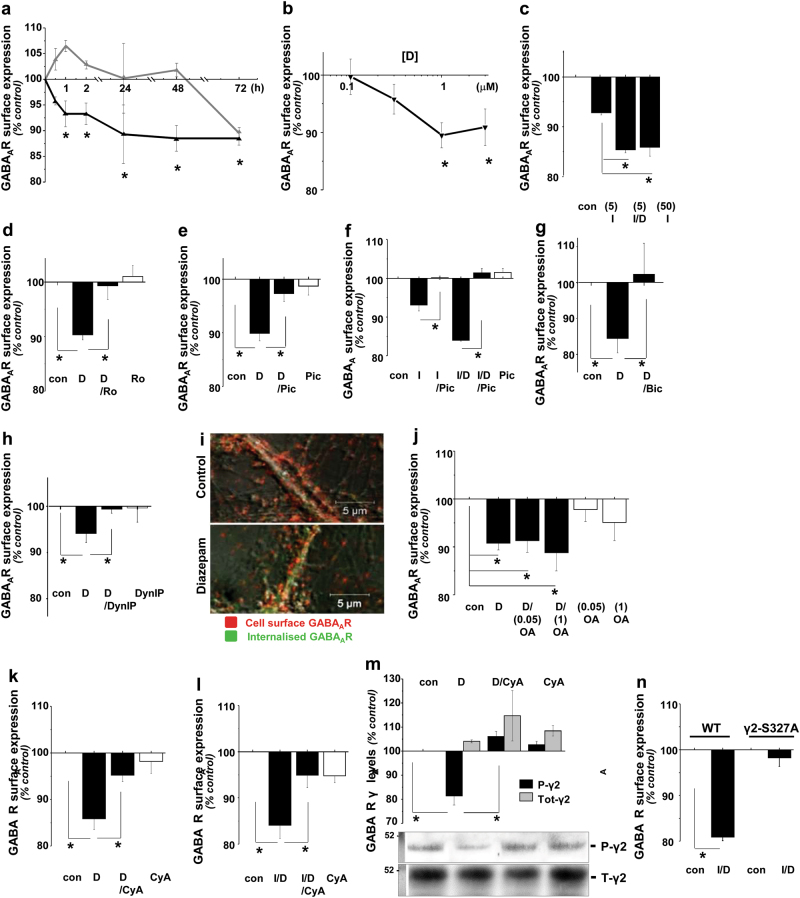

Diazepam triggers internalisation of GABAAR receptors by activating calcineurin

In correlation with diazepam-dependent changes in postsynaptic GABAARs clusters observed in primary cerebrocortical neurones, a significant overall reduction in GABAAR surface expression was detected using a GABAAR β2/3-specific antibody in cell-surface ELISA experiments (Fig. 2). However, a decrease in cell surface levels was detected earlier than the observed disassembly of GABAergic synapses, reaching statistical significance within 1 h, and steady level after 24 h, in the continuous presence of diazepam (Fig. 2a, black line; *p < 0.05). In parallel ELISAs, in which the total levels of GABAARs were measured, a statistically significant decrease was detected after 72 h of continuous diazepam treatment (Fig. 2a, grey line; *p < 0.05). The effects of diazepam were not only time- but also dose-dependent, with the lowest effective concentration of 1 μM (Fig. 2b; *p < 0.05). A significant reduction in surface GABAARs was also observed in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells treated with 1 μM diazepam in the presence of 5 μM isoguvacine (Fig. 2c, *p < 0.05). The observed decrease in surface GABAARs in neurones was abolished in the presence of Ro 15-1788 (Fig. 2d; *p < 0.05), again confirming that this process was initiated by direct diazepam binding to GABAARs. Moreover, this decrease in surface GABAARs was also abolished by picrotoxin, a GABAAR channel blocker, in neurones and in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells (Fig. 2e, f, respectively; *p < 0.05), and by bicuculline (Fig. 2g; *p < 0.05), a competitive antagonist which blocked the binding of GABA to these receptors in neurones. Thus, the observed reduction in surface levels of GABAARs appears to be a consequence of prolonged diazepam-dependent stimulation of their activity evoked by endogenous GABA released from spontaneously active GABAergic neurones in culture (Fig. 1e) or by isoguvacine in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells.

Fig. 2.

Time and dose-dependent internalisation of GABAARs in response to diazepam requires calcineurin activity. a Diazepam (D; 1 μM)-dependent decrease in surface (black) and total (grey) levels of GABAARs over time (n = 5), and b in surface levels only in the presence of increasing doses for 2 h (n = 4) in cortical neurones. c Decrease in surface GABAARs in response to low doses of isoguvacine (I; 5 μM) is potentiated by diazepam (D; 1 μM) in α1/β2/γ2myc-HEK293 cell line (n = 6). d–g Diazepam (D; 1 μM)-dependent decrease in surface GABAARs is inhibited by Ro 15-1788 (Ro; 25 μM; d; n = 7), picrotoxin (Pic; 50 μM; e; n = 5), or bicuculline (Bic; 50 μM; g; n = 4) in cortical neurones, and f picrotoxin (Pic; 50 μM; n = 6) in α1/β2/γ2myc-HEK293 cell line. h Diazepam (D; 1 μM)-dependent decrease in surface GABAARs is inhibited by dynamin-inhibitory peptide (DynIP; 25 μM; n = 5) in cortical neurones following 2 h treatments. i Immunolabelling of internalised (green) and surface (red) GABAARs following 2 h treatments with diazepam (D; 1 μM; n = 2; scale bar = 5 µm). j Diazepam (D; 1 μM)-dependent reduction of surface GABAARs is unaffected by inhibition of PP2A or PP1 with low (0.05 μM) or high (1 μM) dose of okadaic acid, respectively (OA; n = 6), but k it is prevented by inhibition of calcineurin by cyclosporine A (CyA; 1 μM; n = 6). l Diazepam (D; 1 μM) /isoguvacine (I; 5 μM)-dependent reduction in surface GABAARs in α1/β2/γ2myc-HEK293 cell line is prevented by inhibition of calcineurin with cyclosporine A (CyA; 1 μM; n = 3). m Diazepam treatments (D; 1 μM; 2 h) cause GABAAR γ2 subunit dephosphorylation at Ser327 in cortical neurones and this is prevented by cyclosporine A (CyA; 1 μM; n = 2). Immunoblotting was done using an anti-PSer327-γ2 or anti-γ2 primary antibody, followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody and a colour reaction. Quantification was done using ImageJ. n Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/isoguvacine (I; 5 μM)-dependent reduction in surface GABAARs in α1/β2/γ2myc-HEK293 cells is abolished by S327A mutation in the γ2 subunit. Changes in surface GABAARs were measured by cell surface ELISA using β2/3-specific antibody in cortical neurones or myc-antibody in α1/β2/γ2myc-HEK293 cells and presented in graphs as mean ± s.e.m., with n = number of independent experiments. Statistical analysis was done using ANOVA with Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05

A time- and dose-dependent decrease in cell surface GABAARs was also observed in the continuous presence of specific agonists of these receptors at higher concentrations, muscimol (50 μM; Supplementary Figure 2; *p < 0.05) in primary neurons, or isoguvacine (50 μM; Fig. 2c; *p < 0.05) in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells. Importantly, a statistically significant diazepam (1 μM)-dependent potentiation of muscimol effect at lower doses (1 or 5 μM muscimol; *p < 0.05), but not at higher doses (10 or 50 μM muscimol; Supplementary Figure 2a; p > 0.05) was observed, suggesting that, at higher agonist concentrations, GABAARs may have reached the maximal level of stimulation in these preparations. That GABAAR activation by muscimol was a necessary trigger for their downregulation from the cell surface was confirmed in neurones in the presence of bicuculline (Supplementary Figure 2c; *p < 0.05) or picrotoxin (Supplementary Figure 2d; *p < 0.05).

Crucially, the diazepam-dependent decrease in GABAARs surface levels in neurones was abolished in the presence of dynamin-inhibitory peptide (Fig. 2h; *p < 0.05), a peptide which is able to penetrate the plasma membrane and inhibit the endocytolic machinery of the cell [28]. This indicates that the underlying cause of reduction at the cell surface was indeed dynamin-dependent endocytosis of GABAARs rather than inhibition in protein synthesis or reduced insertion into the plasma membrane. Dynamin-inhibitory peptide also blocked a reduction in surface GABAARs caused by high doses of muscimol (Supplementary Figure 2e; *p < 0.05). Consistent with this was the loss of cell surface receptors (Fig. 2i, red) and a concomitant intracellular accumulation of endocytosed GABAARs (Fig. 2i, green) in the presence of diazepam (1 μM) or muscimol (50 μM; Supplementary Figure 2f), which were monitored using immunolabelling with the β2/3 antibody and confocal imaging in neurones. A small amount of internalised β2/3 subunits observed in neurones treated with vehicle control was likely due to constitutive internalisation of GABAARs [19]. Likewise, a reduction of surface GABAARs (Supplementary Figure 3b; red), with a concomitant intracellular accumulation of the endocytosed receptors (Supplementary Figure 3b; green), was also observed in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells (Supplementary Figure 3a) treated with the submaximal doses of isoguvacine (5 μM), and this was further potentiated by the addition of diazepam (1 μM).

Dynamin-dependent endocytosis of GABAARs is known to be regulated by the activity of protein kinases and phosphatases which determine the state of phosphorylation of specific residues in the β and γ subunits of these receptors [29], such that dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 1 or 2A [16], or calcineurin (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase 2B [30]), respectively, promotes their internalisation. To establish which of these phosphatases are involved in diazepam-triggered endocytosis of GABAARs, treatments of cultured neurones were carried out in the presence of either low (0.05 μM) or high (1 μM) doses of okadaic acid, to inhibit PP2A or PP2A/PP1, respectively, or in the presence of cyclosporine A (1 μM), to inhibit calcineurin, and surface GABAARs were monitored using cell surface ELISA. Although inhibition of PP2A alone, or both PP2A and PP1, had no effect (Fig. 2j), inhibition of calcineurin significantly attenuated GABAAR endocytosis triggered by diazepam in neurones (1 μM; Fig. 2k; *p < 0.05), or diazepam/isoguvacine (1 μM/5 μM; Fig. 2l, *p < 0.05) in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells, suggesting that dephosphorylation of the γ2 subunit by calcineurin is a necessary step in this process. This was corroborated in immunoblotting experiments with P-Ser327-γ2-specific antibody, in which diazepam-dependent dephosphorylation of the γ2 subunit in neurones was abolished by cyclosporine A (Fig. 2m; *p < 0.05), and further supported by cell surface ELISA experiments in which mutated S327A γ2myc subunit [31] was expressed in the α1β2-HEK293 cell line (Fig. 2n; *p < 0.05).

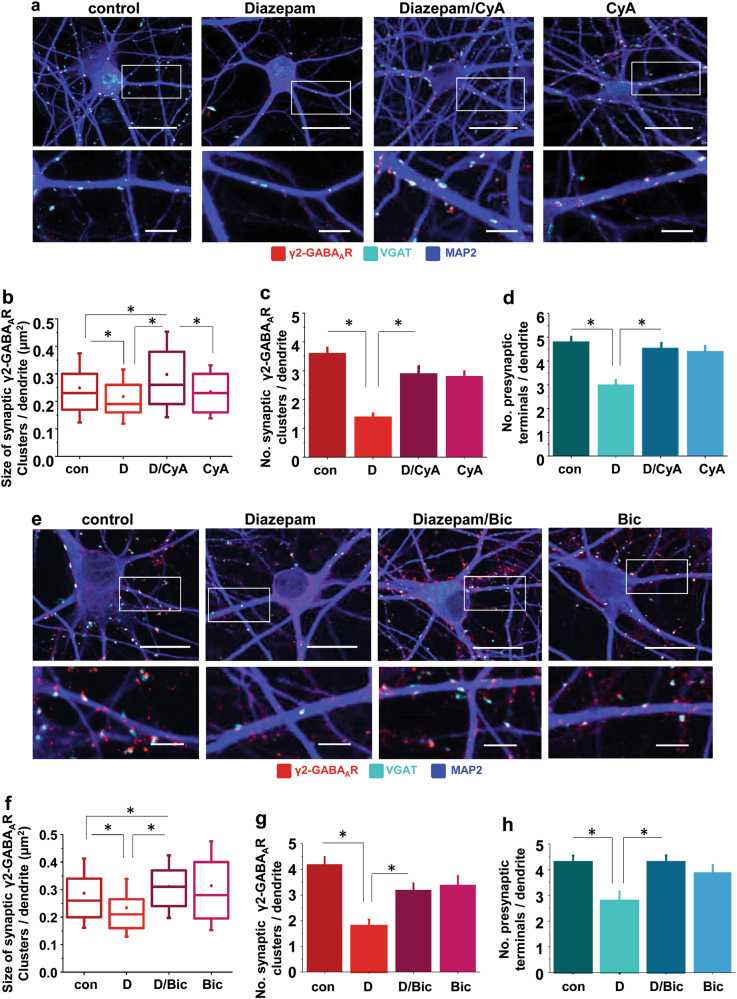

The relationship between diazepam-dependent dephosphorylation and internalisation of GABAARs and subsequent destabilisation of GABAergic synapses was further investigated in experiments in which changes in synaptic elements, the size and number of postsynaptic γ2-GABAAR clusters and the number of colocalised presynaptic GABAergic terminals, were quantitatively assessed following prolonged diazepam treatments (72 h) in the absence or presence of cyclosporine A (Fig. 3a–d). The decrease in size (Fig. 3a, b; *p < 0.05) and number of postsynaptic γ2-GABAAR clusters (Fig. 3a, c; *p < 0.05), and in the number of colocalised presynaptic, VGAT-terminals (Fig. 3a, d; *p < 0.05) detected after 72 h treatment with diazepam, were effectively abolished in the presence of cyclosporine A, further supporting the central role of calcineurin in this process. Moreover, cyclosporine A and diazepam, when applied together, caused a significant increase in the size of GABAAR clusters in comparison with the control, diazepam or cyclosporine A alone (Fig. 3a, b; *p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Diazepam-dependent loss of GABAergic synapses is prevented by inhibition of calcineurin or GABAAR activity. a Immunolabelling of γ2-containing clusters (red) and VGAT-positive presynaptic GABArgic terminals (cyan) along MAP2-positive dendrites (20 µm; blue) following 72 h treatment with control (DMSO) or diazepam (D; 1 μM), in the absence or presence of cyclosporine A (CyA; 1 μM), and corresponding graphs showing b size (median/line-IQRs; mean/dot ± s.d. whiskers; Mann–Whitney test, *p < 0.05), and c number of synaptic γ2 clusters (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05), from n = 71 control dendrites & n = 85, n = 64, n = 73 dendrites of diazepam-, diazepam/cyclosporine A and cyclosporine A-treated cells, respectively, of a total of n = 19, n = 19, n = 18, n = 19 neurons in each group collected from two independent experiments. d Decrease in number of GABAergic terminals (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05) contacting n = 71 control-treated & n = 85, n = 64, n = 73 diazepam-, diazepam/cyclosporine A- or cyclosporine A-treated dendrites for 72 h, respectively, from a total of n = 19, n = 19, n = 18, n = 19 neurons in each group, collected from two independent experiments. e Immunolabelling of γ2-containing clusters (red) and VGAT-positive presynaptic GABArgic terminals (cyan) along MAP2-positive dendrites (20 µm; blue) following 72 h treatment with control (DMSO) or diazepam (D; 1 μM), in the absence or presence of bicuculline (Bic; 50 μM), and corresponding graphs showing f size (median/line-IQRs; mean/dot ± s.d. whiskers; Mann–Whitney test, *p < 0.05), and g number of synaptic γ2 clusters (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05), from n = 60 control dendrites & n = 63, n = 61, n = 65 dendrites of diazepam-, diazepam/bicuculline and bicuculline-treated cells, respectively, of a total of n = 16, n = 19, n = 18, n = 20 neurons in each group collected from two independent experiments. h Decrease in number of GABAergic terminals (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05), contacting n = 60 control-treated & n = 63, n = 61, n = 65 diazepam-, diazepam/bicuculine- or bicuculline-treated dendrites for 72 h, respectively, from a total of n = 16, n = 19, n = 18, n = 20 neurons in each group, collected from two independent experiments. Scale bars = 20 μm (a, e-upper row) and = 5 μm (a, h-lower row)

Furthermore, a functional link between prolonged diazepam-dependent stimulation of GABAARs and disassembly of GABAergic synapses, was assessed in experiments in which structural elements of synapses were analysed in the presence of bicuculline (Fig. 3e–h). Bicuculline significantly attenuated the diazepam-dependent decrease in size (Fig. 3e, f; *p < 0.05) and number of postsynaptic γ2-GABAAR clusters (Fig. 3e, g; *p < 0.05), and in the number of colocalised presynaptic VGAT-terminals (Fig. 3e, h; *p < 0.05). Diazepam and bicuculline added together also caused a significant increase in the size of GABAAR clusters in comparison with control, diazepam or bicuculline treatments alone (Fig. 3e, f; *p < 0.05).

Collectively, these data evince a cascade of signalling events triggered by prolonged stimulation of synaptic GABAARs which, in turn, leads to a calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation and endocytosis of these receptors, and a consequent disassembly of GABAergic synapses. As GABAARs are GABA-gated chloride/bicarbonate channels which are impermeable to Ca2+, while calcineurin activation requires an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+, the question arises as to the nature of the signalling molecules that link the activities of these seemingly unrelated pathways.

Diazepam triggers Ca2+ release from thapsigargin-sensitive intracellular stores by activating PLC

To investigate the functional link between GABAARs and calcineurin, we monitored the intracellular Ca2+ signal using the Ca2+-indicator Fluo-4 in primary neurones by live cell imaging, which has revealed that application of diazepam (1 μM) evokes a prolonged increase in intracellular Ca2+in neuronal dendrites and cell bodies (Fig. 4a, d, e, h; *p < 0.05). Importantly, this increase was completely abolished when diazepam was applied in the presence of Ro 15-1788 (Fig. 4b, d; *p < 0.05) or bicuculline (Fig. 4c, d; *p < 0.05). Furthermore, the rise in intracellular Ca2+ was also abolished when the sarco/endoplasmic Ca2+ stores were depleted in the presence of thapsigargin, a non-competitive inhibitor of Ca2+ ATPase [32], prior to the addition of diazepam (Fig. 4f, h; *p < 0.05). These findings indicate a critical role of the intracellular Ca2+ stores in this process and are consistent with a metabotropic-type signalling classically mediated by phospholipase C (PLC) [33]. To characterise this process further, live imaging of Fluo-4 labelled neurones was carried out in the presence of a general PLC inhibitor U73122 (10 µM), which effectively abolished the increase in intracellular Ca2+ in response to diazepam-dependent activation of GABAARs (Fig. 4g, h; *p < 0.05). In agreement with this, diazepam-dependent down-regulation of surface GABAARs in neurones and in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells was also attenuated by thapsigargin (Fig. 4i, left and right, respectively; *p < 0.05) and U73122 (Fig. 4j; left and right, respectively; *p < 0.05), but not by extracellular chelation of Ca2+ in the presence of EGTA (Fig. 4k; left and right, respectively; *p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Diazepam triggers release of Ca2+ from the intracellular stores which is required for internalisation of GABAARs and prevented by Ro 15-1788, bicuculline, thapsigargin and U-73122. Time lapse imaging of intracellular Ca2+ in Fluo-4-labelled cortical neurones treated with diazepam (D; 1 μM) alone (a, inset: representative images before and after diazepam addition; scale bars = 20 μm), or in the presence of Ro15-1788 (Ro, 25 μM; b) or bicuculine (Bic, 50 μM; c), shown as a fluorescence ratio Ft/F0, and d quantified at the peak of response to diazepam in dendrites and somas (d; mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05; n = 5 neurones in each group from 2 independent experiments). e Diazepam (D; 1 μM)-dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ (insert: representative images before and after diazepam addition; scale bars = 20 μm) is inhibited by thapsigargin (T; 2 μM; f) and U-73122 (U; 10 μM; g). h Ft/F0 was quantified at the peak of response to diazepam in dendrites and somas of labelled cortical neurons (mean ± s.e.m.; ANOVA/Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05; n = 4 neurones in each group from 2 independent experiments). i–k Diazepam (D; 1 μM)-dependent internalisation of GABAARs in neurones (left), and Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM)-dependent internalisation of GABAARs in α1/β2/γ2myc-HEK293 cells (right) are prevented by thapsigargin (T; 2 μM; i) and U-73122 (U; 10 μM; j), but insensitive to EGTA (E; 1 mM; k). Changes in surface GABAARs were measured by cell surface ELISA using β2/3-specific antibody in neurones or myc-antibody in α1/β2/γ2myc-HEK293 cells and presented in graphs as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was done using ANOVA with Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05 (n = 7 thapsigargin, n = 5 U-73122, n = 9 EGTA independent experiments)

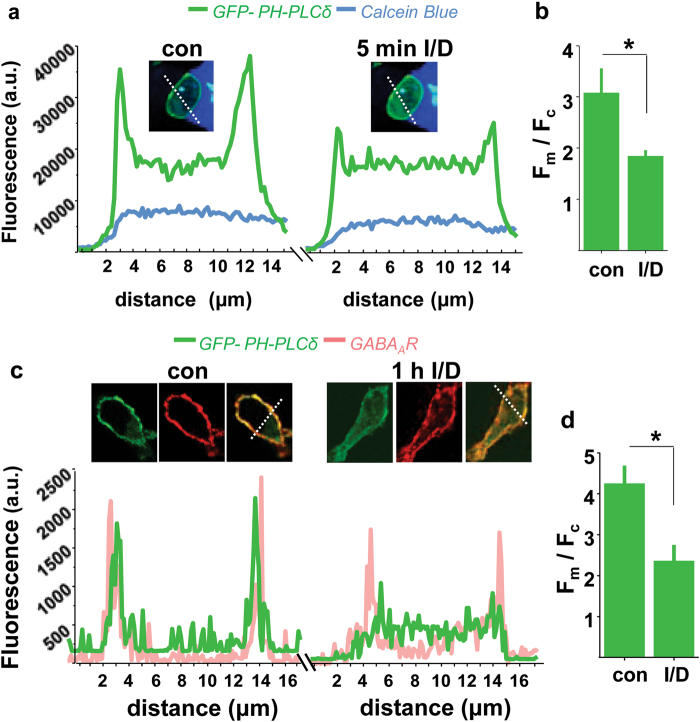

To monitor the activation of PLC by diazepam/isoguvacine, an indirect method was employed in which GFP-tagged PH domain of PLCδ (GFP-PHPLCδ [23]) was expressed in α1β2γ2-HEK293 cell line [18]. In confocal live cell imaging experiments, due to activation of endogenous PLC and depletion of PIP2 in response to diazepam/isoguvacine, the GFP-PHPLCδ, initially predominantly plasma membrane bound (Fm), showed partial translocation to the cytoplasm (Fc) within 5 min (green traces; Fig. 5a), resulting in a significant decrease in Fm/Fc ratio in comparison with controls (Fig. 5b; *p < 0.05). That this activation was long-lasting was shown by fluorescent imaging of GFP-PHPLCδ in α1β2γ2-HEK293 cells (green traces; Fig. 5c), which were fixed after 1 h in continuous presence of diazepam/isoguvacine and immunolabelled with GABAAR-β2-specific antibody at the cell surface (pink traces; Fig. 5c), thus yielded not only a significant decrease in Fm/Fc ratio (Fig. 5d; *p < 0.05), but also a decrease in surface GABAARs.

Fig. 5.

Diazepam/Isoguvacine-dependent translocation of GFP-PHPLCδ1 from the cell membrane to the cytoplasm in α1/β2/γ2-HEK293 cells. a Live imaging of a Calcein blue-labelled cell (inset) showing changes in GFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence intensity profile (green) prior to (left) and 5 min after the addition of Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM) (right). b Quantification of fluorescence F(membrane)/F(cytoplasm) ratio of GFP-PHPLCδ1 (green; mean ± s.e.m.; Student t-test; *p < 0.05; n = 10 cells from 2 independent experiments). c Imaging of surface GABAAR-β2-subunit in fixed HEK293 cells (red) expressing GFP-PHPLCδ1 (green) in control (DMSO, left) and Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM) treated samples for 1 h (right), showing superimposed fluorescence intensity profiles across the selected cells. d Quantification of fluorescence F(membrane)/F(cytoplasm) ratio of GFP-PHPLCδ1 (green; mean ± s.e.m.; Student t-test; *p < 0.05; n = 10 cells from 2 independent experiments)

Collectively, these data indicate that sustained diazepam-dependent activation of GABAARs in neurones, beyond its ionotropic effects, also has a long-lasting metabotropic effect mediated by a PLC/Ca2+/calcineurin signalling cascade which facilitates receptor internalisation from the cell surface.

Regulation of GABAAR interaction with PLCδ or PRIP1 by diazepam

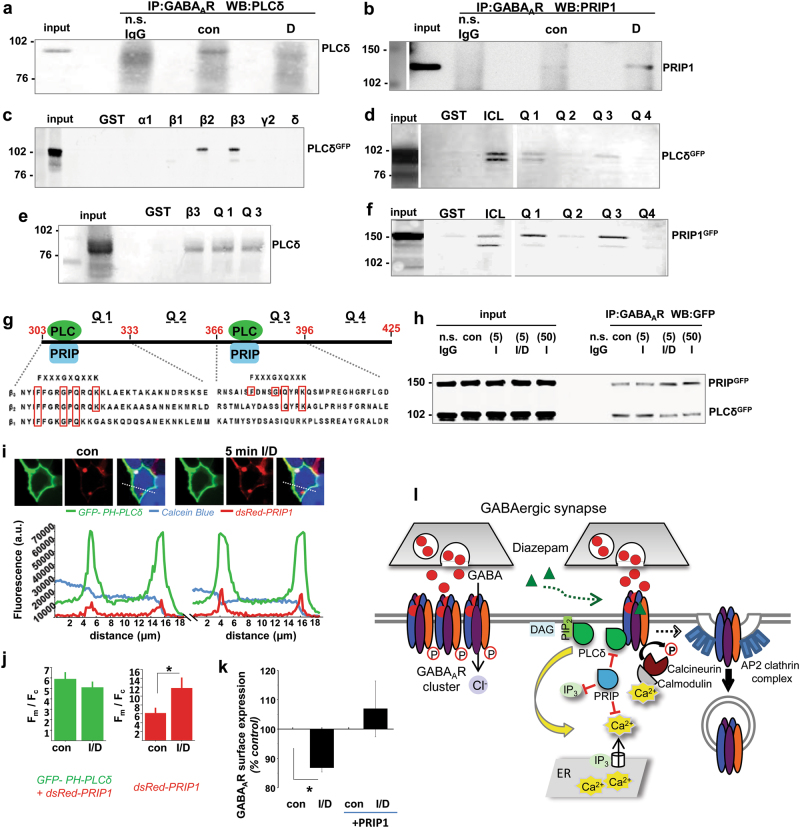

Diazepam/isogivacine-dependent activation of PLC and its requirement in diazepam-dependent mobilisation of intracellular Ca2+ suggests that GABAARs may be in association with some of the 23 known isoforms of PLC [33], via an interaction that might directly impinge on the activity of these enzymes. To test this hypothesis, the PLCδ isoform was initially investigated given its structural similarity to PRIP1 (PLC-related but catalytically inactive protein 1[34]), which has been previously shown to directly associate with GABAARs [35]. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments from control and diazepam-treated neurones demonstrated that PLCδ binds to GABAARs in controls, but disassociates from them when diazepam is applied (Fig. 6a), while PRIP1 shows the opposite translocation (Fig. 6b). To investigate these interactions further, in vitro binding assays were carried out in which purified GST-fusion proteins incorporating the intracellular TM3-4 loop of different GABAAR subunits were incubated with lysates of PLCδ-GFP expressing HEK293 cells, revealing that PLCδ binds to the β2 and β3 subunits of GABAARs specifically (Fig. 5c). Using truncation mutants of the β3 subunit TM3-4 loop, two distinct binding regions, between 303–333 (Q1) and 366–396 (Q3) residues, were identified (Fig. 5d) and, in subsequent experiments, demonstrated to mediate the direct binding of PLCδ (Fig. 5e). Interestingly, PRIP1-GFP was also found to interact with the same Q1 and Q3 regions of the GABAAR β3 subunit as PLCδ (Fig. 5f), suggesting that, in situ, these two proteins may be in competition for their binding to GABAARs. Based on the sequence similarity in the Q1 and Q3 regions between the β2 and β3 subunits, a potential binding sequence for both PLCδ and PRIP1 was identified (FXXXGXQXXK; Fig. 5g).

Fig. 6.

Diazepam triggers dissociation of PLCδ from GABAARs in situ leading to activation of PLCδ/Ca2+/calcineurin signalling pathway, which is negatively regulated by PRIP1. a Immunoprecipitates of GABAARs from control and diazepam (D; 1 μM)-treated cortical neurones were probed with PLCδ- (n = 3) or b PRIP1- (n = 4) specific antibody. c–e PLCδ-GFP binds directly to the intracellular loop of the GABAAR β2 and β3 subunits Q1 (303-366 aa) and Q3 (366-396 aa) regions in GST pull-down assays (n = 3). f PRIP1-GFP binds directly to the β3 subunit Q1 and Q3 loop regions in the GST pull-down assays (n = 3). g Predicted PLCδ- and PRIP1- binding sites in the Q1 and Q3 regions of the β2 and β3 subunits. h Immunoprecipitates of GABAARs from control (DMSO) or Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM)-, Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM)- or Isoguvacine (I; 50 μM)-treated α1β2γ2-GABAAR HEK293 cells expressing both GFP-PLCδ and GFP-PRIP1 were probed with the GFP-specific antibody (n = 2). (i) Overexpression of PRIP1 inhibits partial translocation of GFP-PHPLCδ1 in response to Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM) in α1β2γ2-HEK293 cells. Live imaging of a Calcein blue-labelled cell (blue) expressing GFP-PHPLCδ1 (green) and dsRed-PRIP1 (red; top panels) and superimposed fluorescence intensity profiles prior to (left) and 5 min after the addition of Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM) (right). j Quantification of fluorescence F(membrane)/F(cytoplasm) ratio of GFP-PHPLCδ1 (green; left) and dsRed-PRIP1 (red; right), both shown as mean ± s.e.m. (Student t-test; *p < 0.05; n = 10 cells from 2 independent experiments). k Overexpression of PRIP1 inhibits Diazepam (D; 1 μM)/Isoguvacine (I; 5 μM)-dependent internalisation of GABAARs. Changes in surface GABAARs were measured by cell surface ELISA with anti-myc-specific antibody labelling the γ2 subunit, and presented as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4). Statistical analysis was done using ANOVA with Bonferonni post-hoc test; *p < 0.05; n = number of independent experiments. l Schematic diagram of the GABAAR/PLCδ/Ca2+/calcineurin feed-back mechanism underlying diazepam-dependent downregulation of GABAARs. According to this model, sustained activation of synaptic GABAARs by diazepam triggers a metabotropic, PLCδ/Ca2+/calcineurin signalling pathway which leads to receptor dephosphorylation by calcineurin, initiation of dynamin-dependent endocytosis resulting in a decrease in the size and number of postsynaptic GABAAR clusters, and disassembly of inhibitory synapses. This mechanism is ‘switched off’ when PRIP1, PLCδ-related but catalytically inactive protein, outcompetes the PLCδ in binding to GABAARs, thereby preventing the activation of PLCδ and downstream Ca2+/calcineurin-dependent internalisation of these receptors

Dissociation of PLCδ from GABAARs upon their activation by diazepam/isoguvacine and the concurrent increase in PRIP1 binding were confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation from lysates of α1β2γ2-HEK293 cells transfected with GFP-PLCδ and GFP-PRIP1 cDNA (Fig. 5h), further supporting the observation that the binding of these proteins is regulated by the level of GABAAR activation, but in a mutually exclusive manner.

Altogether, the data suggest that a switch in association between GABAARs and catalytically-active PLCδ versus catalytically inactive PRIP1, may be a critical regulatory step in the signalling pathway that leads to diazepam-dependent internalisation of GABAARs. To test this hypothesis, the intracellular localisation of GFP-PHPLCδ and dsRed-PRIP1 was monitored simultaneously by live cell imaging in transfected α1β2γ2-HEK293 cells before and 5 min after the bath application of diazepam/isoguvacine (Fig. 6i). GFP-PHPLCδ showed no apparent translocation from the membrane to the cytoplasm (green traces, Fig. 6i) and no change in Fm/Fc ratio (Fig. 6j, left) when dsRed-PRIP1 was also expressed, suggesting that activation of endogenous PLCδ in response to diazepam/isoguvacine was blocked. In contrast, dsRed-PRIP1 showed further accumulation in the plasma membrane (red traces, Fig. 6i) resulting in an increase in Fm/Fc ratio (Fig. 6j, right). Moreover, a decrease in surface GABAARs in response to diazepam/isoguvacine in α1β2γ2myc-HEK293 cells detected by cell surface ELISA, was completely abolished by overexpression of PRIP1 (Fig. 5k), suggesting that PRIP1 may serve as an inhibitor of this signalling pathway, thereby preventing the process of GABAARs internalisation and alleviating the consequent loss of inhibitory GABAergic synapses (Fig. 5l).

Discussion

The prevalence of stress-related psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety mixed with depression, panic attacks or insomnia, leads to an estimated 12 million prescriptions of benzodiazepines every year in the UK (UK Addiction Treatment Centres). However, our current understanding of the long-term effects of benzodiazepines on cellular and molecular processes in the brain remains limited.

In this study we have revealed that prolonged exposure of neurons to diazepam activates a novel Ca2+ signalling cascade downstream of GABAARs, which in a negative feedback fashion, leads to a gradual removal of these receptors from the postsynaptic membrane and disassembly of inhibitory synapses, thus rendering the system unresponsive to any further diazepam treatments. Although studied in vitro, these processes are closely correlated in time to in vivo downregulation of GABAARs and the onset of tolerance to benzodiazepines in rodents [36]. These processes are however in sharp contrast with the initial diazepam-dependent facilitation of GABAAR channel gating activity [25], increased mobilisation of GABAARs to synapses [37, 38], and enhanced inhibitory synaptic transmission [39], possibly representing a form of neuronal adaptation in order to maintain a critical balance between the excitation and inhibition in the brain.

Our experiments demonstrate that sustained activation of GABAARs by diazepam, in the presence of ambient GABA (Fig. 1e [39]), is a key trigger of this signalling cascade which involves PLCδ activation, mobilisation of intracellular Ca2+ and activation of calcineurin. A key role of calcineurin in diazepam-dependent endocytosis of GABAARs is in agreement with the previously reported effects on GABAAR migration out of the synaptic contacts [31, 40, 41], and internalisation from the cell surface [42]. Subsequent loss of inhibitory synapses indicates that depletion of postynaptic GABAARs destabilises synaptic contacts, an observation consistent with their activity-dependent regulation reported previously [43], and also with a direct structural role of GABAARs in the formation of these synapses [17, 44, 45]. As changes in cell surface GABAARs are known to precede changes in the postsynaptic gephyrin scaffold [46], our findings are also in agreement with the previously observed diazepam-dependent reduction in the size of gephyrin clusters [47]. At later time points of incubation with diazepam, an overall reduction in GABAAR expression is likely to occur due to induced proteolysis of internalised receptors, as previously reported for the prolonged flurazepam treatments [48], or due to a decrease in the rate of transcription and/or translation of GABAAR subunits, as shown in vivo by monitoring the mRNA levels [10, 11, 15, 49].

Another important step in this cascade is diazepam-dependent rise in intracellular Ca2+ originating from the thapsigargin-sensitive intracellular stores and mediated by the activation of PLCδ, which is consistent with a metabotropic-type signalling by GABAARs in mature neurones operating in addition to their ‘canonical’ ionotropic signalling as chloride/bicarbonate channels. In contrast to immature neurones, where GABAAR activation generally leads to depolarisation and influx of Ca2+ through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [50, 51], this signalling pathway is insensitive to the extracellular chelation of Ca2+ with EGTA. Furthermore, the requirement for PLC activity in this process is in agreement with the biochemical evidence for a direct association between GABAAR β subunits and PLCδ, which was also detected in recent proteomic analyses of GABAAR binding proteins [52, 53]. Although PLCδ may not be the only isoform of PLC able to interact with GABAARs, its extensive structural similarity with PRIP1, a well characterised GABAAR receptor interacting protein [54], is of significance. Interestingly, our experiments demonstrate that PLCδ disassociates from GABAARs with diazepam treatments, suggesting that this displacement may be required for its activation, particularly if the PLCδ binding to GABAARs resembles its binding to calmodulin via an auto-inhibitory region which renders it inactive [55]. Exactly how dissociation of PLCδ from GABAARs occurs remains to be elucidated, although we hypothesise that this could be caused by a conformational change in the receptor upon activation, or by accumulation of negatively charged chloride and depletion of bicarbonate, possibly changing the pH or osmolality [56] in the vicinity of the receptor. At the same time, however, these conditions facilitate the binding of PRIP1 to GABAARs, which, together with identified common binding sites in the β subunits, suggests that the two proteins may be in competition with each other. The interplay between PLCδ and PRIP1 in binding to GABAARs may represent an important on/off switching mechanism regulating this signalling pathway and downstream endocytosis of GABAARs. This is because PRIP proteins are not only catalytically inactive variants of PLCδ unable to generate IP3 and DAG [34], but they also inhibit PLC signalling due to high affinity binding of IP3, thereby sequestering it away from the IP3 receptor on the intracellular Ca2+ stores [57]. That overexpression of PRIP1 inhibited diazepam-dependent activation of PLCδ and diazepam-dependent down-regulation of surface GABAARs in heterologous systems, suggests that this protein can act as an inhibitor by outcompeting the PLCδ binding to GABAARs. In neurones, PRIP1 is likely to be a temporary block of this pathway, due to its removal together with GABAARs undergoing endocytosis [58]. This is in agreement with the effects of PRIP gene deletion in mice, which show increased intracellular Ca2+ and calcineurin activity [57], decreased levels of synaptic γ2-containing GABAARs receptors, reduced sensitivity to diazepam and increased anxiety-like behaviour [59]. We therefore hypothesise that, when the ‘off’ switch (PRIP) is no longer present, PLCδ recruitment to GABAARs allows continuous activation of this signalling pathway and depletion of synaptic GABAA receptors, leading to their structural and functional deficits in inhibitory synapses. This diazepam-induced breakdown of inhibitory GABAergic synapses not only correlates well in time with the development of tolerance but also provides a likely explanation for the severe withdrawal symptoms, increased anxiety and even seizures, observed in animal models and patients following sudden termination of chronic benzodiazepine treatment [60], possibly due to uncontrolled excitatory drive in the absence of functional inhibition.

This signalling mechanism offers a new spectrum of possible molecular interventions that could be tailored towards extending the initial highly beneficial clinical outcomes of benzodiazepines, while preventing the subsequent disruption of GABAergic synapses and development of pharmacological and behavioural tolerance to these widely prescribed drugs.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council UK New Investigator Grant BB/C507237/1 (to J.N.J), Medical Research Council UK project grant (G0800498), Wellcome Trust and UCL School of Pharmacy funds. We thank Professor Jean-Marc Fritschy (University of Zurich) and Professor Anne Stephenson for providing us with the GABAA γ2 subunit- and α1-specific antibodies, respectively, Professor Masato Hirata and Dr Akiko Mizokami (Kyushu University) for GFP-PRIP1 and dsRed-PRIP1 cDNAs, and PRIP-specific antibodies, Dr Steve Marsh (UCL) for GFP-PHPLCδ cDNA, Dr Lorena Arancibia-Carcamo and Professor Josef Kittler (UCL) for mutant S327A γ2 subunit cDNA, and Gianandrea Broglia and Ljubi Sihra-Jovanovic for technical assistance. We thank Professor Talvinder Sihra (UCL Department of Neuroscience, Physiology and Pharmacology) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41380-018-0100-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Rudolph U, Knoflach F. Beyond classical benzodiazepines: novel therapeutic potential of GABAA receptor subtypes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:685–97. doi: 10.1038/nrd3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiers N, Qassem T, Bebbington P, McManus S, King M, Jenkins R, et al. Prevalence and treatment of common mental disorders in the English national population, 1993–2007. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:150–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.174979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lader M. Benzodiazepine harm: how can it be reduced? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:295–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lugoboni F, Quaglio G. Exploring the dark side of the moon: the treatment of benzodiazepine tolerance. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:239–41. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downing SS, Lee YT, Farb DH, Gibbs TT. Benzodiazepine modulation of partial agonist efficacy and spontaneously active GABA(A) receptors supports an allosteric model of modulation. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:894–906. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gielen MC, Lumb MJ, Smart TG. Benzodiazepines modulate GABAA receptors by regulating the preactivation step after GABA binding. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5707–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5663-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohler H. The legacy of the benzodiazepine receptor: from flumazenil to enhancing cognition in Down syndrome and social interaction in autism. Adv Pharmacol. 2015;72:1–36. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieghart W. Structure, pharmacology, and function of GABAA receptor subtypes. Adv Pharmacol. 2006;54:231–63. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(06)54010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luscher B, Fuchs T, Kilpatrick CL. GABAA receptor trafficking-mediated plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Neuron. 2011;70:385–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bateson AN. Basic pharmacologic mechanisms involved in benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:5–21. doi: 10.2174/1381612023396681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinkers CH, Olivier B. Mechanisms underlying tolerance after long-term benzodiazepine use: a future for subtype-selective GABA(A) receptor modulators? Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2012;2012:416864. doi: 10.1155/2012/416864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roca DJ, Rozenberg I, Farrant M, Farb DH. Chronic agonist exposure induces down-regulation and allosteric uncoupling of the gamma-aminobutyric acid/benzodiazepine receptor complex. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;37:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravielle MC. Activation-induced regulation of GABAA receptors: is there a link with the molecular basis of benzodiazepine tolerance? Pharmacol Res. 2016;109:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rijnsoever C, Tauber M, Choulli MK, Keist R, Rudolph U, Mohler H, et al. Requirement of alpha5-GABAA receptors for the development of tolerance to the sedative action of diazepam in mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6785–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1067-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uusi-Oukari M, Korpi ER. Regulation of GABA(A) receptor subunit expression by pharmacological agents. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:97–135. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jovanovic JN, Thomas P, Kittler JT, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates fast synaptic inhibition by regulating GABA(A) receptor phosphorylation, activity, and cell-surface stability. J Neurosci. 2004;24:522–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3606-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown LE, Nicholson MW, Arama JE, Mercer A, Thomson AM, Jovanovic JN. gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A (GABAA) receptor subunits play a direct structural role in synaptic contact formation via their N-terminal extracellular domains. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:13926–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.714790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs C, Abitbol K, Burden JJ, Mercer A, Brown L, Iball J, et al. GABA(A) receptors can initiate the formation of functional inhibitory GABAergic synapses. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38:3146–58. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goffin D, Ali AB, Rampersaud N, Harkavyi A, Fuchs C, Whitton PS, et al. Dopamine-dependent tuning of striatal inhibitory synaptogenesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2935–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4411-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan M, Wurm F. Transfection of adherent and suspended cells by calcium phosphate. Methods. 2004;33:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollard S, Duggan MJ, Stephenson FA. Further evidence for the existence of alpha subunit heterogeneity within discrete gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor subpopulations. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3753–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenzie M, Duchen MR. Impaired cellular bioenergetics causes mitochondrial calcium handling defects in MT-ND5 mutant cybrids. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0154371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stauffer TP, Ahn S, Meyer T. Receptor-induced transient reduction in plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:343–6. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanematsu T, Yasunaga A, Mizoguchi Y, Kuratani A, Kittler JT, Jovanovic JN, et al. Modulation of GABA(A) receptor phosphorylation and membrane trafficking by phospholipase C-related inactive protein/protein phosphatase 1 and 2A signaling complex underlying brain-derived neurotrophic factor-dependent regulation of GABAergic inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22180–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers CJ, Twyman RE, Macdonald RL. Benzodiazepine and beta-carboline regulation of single GABAA receptor channels of mouse spinal neurones in culture. J Physiol. 1994;475:69–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson SM, Czajkowski C. Structural mechanisms underlying benzodiazepine modulation of the GABA(A) receptor. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3490–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5727-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman H, Greenblatt DJ, Peters GR, Metzler CM, Charlton MD, Harmatz JS, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral diazepam: effect of dose, plasma concentration, and time. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;52:139–50. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kittler JT, Delmas P, Jovanovic JN, Brown DA, Smart TG, Moss SJ. Constitutive endocytosis of GABAA receptors by an association with the adaptin AP2 complex modulates inhibitory synaptic currents in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7972–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07972.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura Y, Darnieder LM, Deeb TZ, Moss SJ. Regulation of GABAARs by phosphorylation. Adv Pharmacol. 2015;72:97–146. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Liu S, Haditsch U, Tu W, Cochrane K, Ahmadian G, et al. Interaction of calcineurin and type-A GABA receptor gamma 2 subunits produces long-term depression at CA1 inhibitory synapses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:826–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00826.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muir J, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, MacAskill AF, Smith KR, Griffin LD, Kittler JT. NMDA receptors regulate GABAA receptor lateral mobility and clustering at inhibitory synapses through serine 327 on the gamma2 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16679–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000589107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treiman M, Caspersen C, Christensen SB. A tool coming of age: thapsigargin as an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:131–5. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(98)01184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunney TD, Katan M. PLC regulation: emerging pictures for molecular mechanisms. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugiyama G, Takeuchi H, Kanematsu T, Gao J, Matsuda M, Hirata M. Phospholipase C-related but catalytically inactive protein, PRIP as a scaffolding protein for phospho-regulation. Adv Biol Regul. 2013;53:331–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terunuma M, Jang IS, Ha SH, Kittler JT, Kanematsu T, Jovanovic JN, et al. GABAA receptor phospho-dependent modulation is regulated by phospholipase C-related inactive protein type 1, a novel protein phosphatase 1 anchoring protein. J Neurosci: Off J Soc Neurosci. 2004;24:7074–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1323-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller LG, Greenblatt DJ, Barnhill JG, Shader RI. Chronic benzodiazepine administration. I. Tolerance is associated with benzodiazepine receptor downregulation and decreased gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;246:170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gouzer G, Specht CG, Allain L, Shinoe T, Triller A. Benzodiazepine-dependent stabilization of GABA(A) receptors at synapses. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2014;63:101–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levi S, Le Roux N, Eugene E, Poncer JC. Benzodiazepine ligands rapidly influence GABAA receptor diffusion and clustering at hippocampal inhibitory synapses. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mozrzymas JW, Wojtowicz T, Piast M, Lebida K, Wyrembek P, Mercik K. GABA transient sets the susceptibility of mIPSCs to modulation by benzodiazepine receptor agonists in rat hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2007;585(Pt 1):29–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bannai H, Levi S, Schweizer C, Inoue T, Launey T, Racine V, et al. Activity-dependent tuning of inhibitory neurotransmission based on GABAAR diffusion dynamics. Neuron. 2009;62:670–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bannai H, Niwa F, Sherwood MW, Shrivastava AN, Arizono M, Miyamoto A, et al. Bidirectional control of synaptic GABAAR clustering by glutamate and calcium. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2768–80. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eckel R, Szulc B, Walker MC, Kittler JT. Activation of calcineurin underlies altered trafficking of alpha2 subunit containing GABAA receptors during prolonged epileptiform activity. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang ZJ. Activity-dependent development of inhibitory synapses and innervation pattern: role of GABA signalling and beyond. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 9):1881–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown LE, Fuchs C, Nicholson MW, Stephenson FA, Thomson AM, Jovanovic JN, et al. Inhibitory synapse formation in a co-culture model incorporating GABAergic medium spiny neurons and HEK293 cells stably expressing GABAA receptors. J Vis Exp. 2014; e52115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Fuchs C, Abitbol K, Burden JJ, Mercer A, Brown L, Iball J, et al. GABA(A) receptors can initiate the formation of functional inhibitory GABAergic synapses. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38:3146–58. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niwa F, Bannai H, Arizono M, Fukatsu K, Triller A, Mikoshiba K. Gephyrin-independent GABA(A)R mobility and clustering during plasticity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vlachos A, Reddy-Alla S, Papadopoulos T, Deller T, Betz H. Homeostatic regulation of gephyrin scaffolds and synaptic strength at mature hippocampal GABAergic postsynapses. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:2700–11. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacob TC, Michels G, Silayeva L, Haydon J, Succol F, Moss SJ. Benzodiazepine treatment induces subtype-specific changes in GABA(A) receptor trafficking and decreases synaptic inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:18595–18600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204994109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huopaniemi L, Keist R, Randolph A, Certa U, Rudolph U. Diazepam-induced adaptive plasticity revealed by alpha1 GABAA receptor-specific expression profiling. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1059–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porcher C, Hatchett C, Longbottom RE, McAinch K, Sihra TS, Moss SJ, et al. Positive feedback regulation between gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA(A)) receptor signaling and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release in developing neurons. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21667–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1215–84. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamura Y, Morrow DH, Modgil A, Huyghe D, Deeb TZ, Lumb MJ, et al. Proteomic characterization of inhibitory synapses using a novel pHluorin-tagged gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor, Type A (GABAA), alpha2 subunit knock-in mouse. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:12394–407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.724443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uezu A, Kanak DJ, Bradshaw TW, Soderblom EJ, Catavero CM, Burette AC, et al. Identification of an elaborate complex mediating postsynaptic inhibition. Science. 2016;353:1123–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aag0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanematsu T, Takeuchi H, Terunuma M. Hirata M. PRIP, a novel Ins(1,4,5)P3 binding protein, functional significance in Ca2+ signaling and extension to neuroscience and beyond. Mol Cells. 2005;20:305–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sidhu RS, Clough RR, Bhullar RP. Regulation of phospholipase C-delta1 through direct interactions with the small GTPase Ral and calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21933–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chavas J, Forero ME, Collin T, Llano I, Marty A. Osmotic tension as a possible link between GABA(A) receptor activation and intracellular calcium elevation. Neuron. 2004;44:701–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toyoda H, Saito M, Sato H, Tanaka T, Ogawa T, Yatani H, et al. Enhanced desensitization followed by unusual resensitization in GABAA receptors in phospholipase C-related catalytically inactive protein-1/2 double-knockout mice. Pflug Arch. 2015;467:267–84. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kanematsu T, Fujii M, Mizokami A, Kittler JT, Nabekura J, Moss SJ, et al. Phospholipase C-related inactive protein is implicated in the constitutive internalization of GABAA receptors mediated by clathrin and AP2 adaptor complex. J Neurochem. 2007;101:898–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanematsu T, Jang IS, Yamaguchi T, Nagahama H, Yoshimura K, Hidaka K, et al. Role of the PLC-related, catalytically inactive protein p130 in GABA(A) receptor function. EMBO J. 2002;21:1004–11. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schoch P, Moreau JL, Martin JR, Haefely WE. Aspects of benzodiazepine receptor structure and function with relevance to drug tolerance and dependence. Biochem Soc Symp. 1993;59:121–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.