Abstract

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) has diagnostic and therapeutic value in the management of salivary gland cysts. Rendering an accurate diagnosis from an aspirated salivary gland cyst is challenging because of the broad differential diagnosis, possibility of sampling error, frequent hypocellularity of specimens, morphologic heterogeneity, and overlapping cytomorphology of many cystic entities. To date, there have been no comprehensive review articles providing a practical diagnostic approach to FNA of cystic lesions of salivary glands. This article reviews the cytopathology of salivary gland cysts employing 2017 World Health Organization terminology, addresses the accuracy of FNA, and presents The Milan System approach for reporting in cystic salivary gland cases. The utility of separating FNA specimens from salivary gland cysts, based upon the presence of mucin and admixed lymphocytes in cyst fluid is demonstrated. A reliable approach to interpreting FNA specimens from patients with cystic salivary gland lesions is essential to accurately determine which of these patients may require subsequent surgery.

Keywords: Fine-needle, Cyst fluid, Cysts, Cytology, Salivary glands, Milan system

Introduction

Several non-neoplastic lesions, benign neoplasms, and malignancies of the salivary gland can present with a predominant or minor cystic component [1, 2]. It is important to distinguish these lesions from one another because patient management often differs among these groups. At least one-third of cystic salivary gland lesions are neoplastic [3]. Table 1 lists common cystic salivary gland lesions likely to be encountered. Non-neoplastic cystic salivary gland lesions can be divided into true cysts (e.g., lymphoepithelial cyst) and non-developmental cysts (e.g., retention cyst) [4]. Occasionally, one may also encounter more rare cystic lesions in the salivary gland such as an epidermoid cyst [5], keratocystoma [6], odontogenic keratocyst [7], and primary hydatid cyst in endemic regions [8]. Salivary gland cysts can typically be identified by ultrasound. However, occasionally, benign or malignant tumors (e.g., lymphoma, metastases) can be misinterpreted as a simple cyst, pseudocysts can be hard to discern, and paradoxically certain cystic lesions can present as solid lesions on ultrasound [9]. FNA is frequently utilized for diagnostic purposes, and when needed, can be used therapeutically to drain benign cysts. Employing FNA early on in the diagnostic work-up of patients can help avoid unnecessary surgery.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of cystic salivary gland lesions

(adapted from Pusztaszeri et al. [3])

| Salivary gland origin | Non-neoplastic | Neoplastic |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | Obstructive sialadenopathy (mucus retention cyst, mucocele), lymphoepithelial cyst, sclerosing polycystic adenosis, polycystic (dysgenetic) disease, epidermoid cyst, first branchial arch anomalies, hydatid cyst | Warthin tumor, sebaceous adenoma, sebaceous lymphadenoma, intraductal papilloma, pleomorphic adenoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, secretory carcinoma, any neoplasm (e.g., lymphoma) with cystic degeneration, metastatic carcinoma to intra-glandular node |

| Extrinsic | Second branchial cleft cyst, cystic hygroma | Metastatic carcinoma with cystic necrosis to peri-glandular node |

FNA of cystic lesions in the head and neck region is notoriously challenging because many disparate entities may present with similar cytological findings [10–12]. Moreover, FNA of cystic salivary gland lesions are typically of low cellularity. The rate of inadequate sampling and false negative results is increased in cystic lesions compared with solid tumors [13, 14]. The diagnostic value of FNA can be increased if, after drainage of cyst fluid, any residual solid components are also sampled. FNA may yield mucoid (mucin) or non-mucoid (e.g., serous) material. For this reason aspirates of cystic salivary gland lesions are typically divided into “mucinous” and “non-mucinous types” (Fig. 1). Mucin (mucicarmine-positive) may be viscous and resemble thick colloid-like material. Non-mucinous cyst contents are generally more watery, proteinaceous and may contain scattered acute and/or chronic inflammatory cells (e.g., lymphocytes, macrophages) and debris. Crystals may sometimes also be identified.

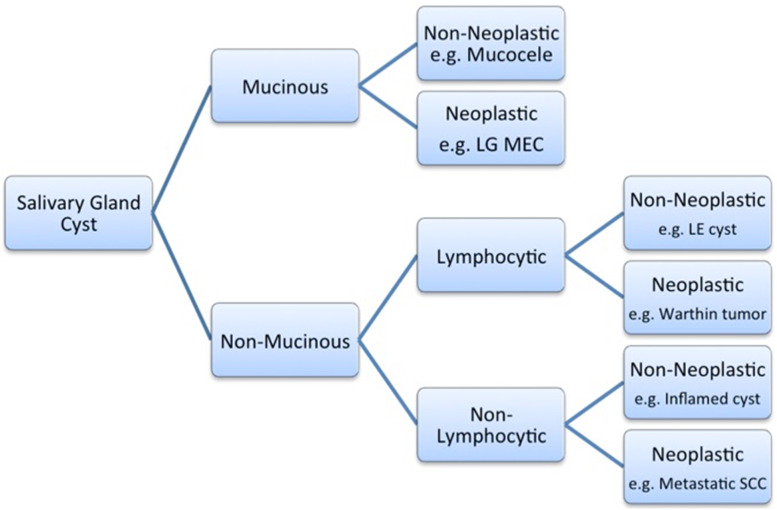

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of a diagnostic approach to FNA of salivary gland cysts based on the microscopic presence of mucin associated with and without admixed lymphocytes. LG MEC low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, LE lymphoepithelial, SCC squmous cell carcinoma

Only a limited number of articles have reported cytopathology studies of cystic salivary gland lesions [15–18]. The largest study to date from Johns Hopkins reviewed 145 FNA cases of cystic major salivary gland lesions in which the majority (84.8%) of patients had follow-up data available [17]. In this series most (79.3%) cases were non-neoplastic, several (11.0%) were reported as “favor non-neoplastic, but cannot rule out neoplasm”, and only 1 (0.7%) was diagnosed as malignant (squamous cell carcinoma). On follow-up, the 13 cases which turned out to be malignant had been diagnosed on cytology as non-neoplastic (n = 6, 5.8%), suspicious for a neoplasm (n = 6, 60%), and malignant (n = 1, 100%). In another series of 56 cystic lesions of salivary glands, investigators noted that the presence of atypical squamous metaplasia in oncocytic lesions was an important cause of false-positive diagnoses of carcinoma, and that FNA samples of low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) may sometimes contain no epithelial cells and consequently result in false-negative diagnoses [15]. In another study evaluating only 8 cases with subsequent surgical resection, “non-diagnostic” FNA cases (with non-mucinous background) were determined to be benign (lymphoepithelial or duct cysts) whilst those categorized as “atypical” (with a mucinous background and no epithelial component) were found to be either benign (mucocele) or neoplastic (pleomorphic adenoma with cystic degeneration and low-grade cystic MEC) [18].

Accuracy of FNA

In general, FNA of salivary gland lesions has good sensitivity (86–100%) and specificity (90–100%) [19]. Accuracy of FNA to distinguish benign from malignant salivary gland lesions is also respectable (81–100%), but to some extent less so (48–94%) when used to specifically subtype salivary gland neoplasms [19]. FNA diagnostic accuracy of salivary gland cysts has performed equally well. In the study reported by Layfield and Gopez (n = 56 patients), FNA of cystic salivary gland lesions demonstrated an overall diagnostic accuracy of 84% [15]. In the study reported by Edwards and Wasserman (n = 97 cases, where 21 had histologic follow-up), FNA resulted in a correct diagnosis in 72% and clinically significant misdiagnoses in 14% of cases [16]. In another study (n = 37 cases) the concordance of FNA with histopathology for salivary gland cystic masses was 92%, whereas it showed a sensitivity of 77%, specificity of 100%, positive predicitve value (PPV) of 100% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 89% [20]. Allison et al. in their FNA series (n = 145 cases) reported a sensitivity of 41.6%, specificity of 99%, PPV of 90.9%, and NPV of 87.6% for the detection of cystic salivary gland neoplasms [17]. In this latter study, cases containing mucin performed exceptionally well, showing 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity for the detection of neoplasms (Table 2), especially MEC. This finding justifies dividing cyst fluid samples into those with and without mucin for evaluation.

Table 2.

FNA performance for diagnosing cystic salivary gland neoplasms

(adapted from Allison et al. [17])

| Diagnostic category | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoplasms | All | Malignant | All | Malignant | All | Malignant | All | Malignant |

| All cases | 41.6 | 50.0 | 99.0 | 96.4 | 90.9 | 60.0 | 87.6 | 94.7 |

| Mucinous | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Non-mucinous (lymphocytic) | 9.1 | 20.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 85.0 | 93.4 |

| Non-mucinous (non-lymphocytic) | 44.4 | 33.3 | 97.7 | 92.0 | 80.0 | 20.0 | 89.6 | 95.8 |

The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology

Table 3 illustrates how various cystic salivary gland lesions are handled according to the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC). Acellular aspirates from cystic non-mucinous lesions are classified as non-diagnostic (cystic fluid only) while hypocellular samples with mucinous material are classified as atypia of undetermined significance (AUS) [3]. However, these two diagnostic categories should only be used after all cyst contents have been processed and examined. If FNA findings show only necrotic debris they should be reported as non-diagnostic with a comment that this finding raises the possibility of a neoplastic process. Given that aspirates with only scant epithelial cells and mucinous cyst contents may represent a low-grade MEC, they are considered to be indefinite for a neoplasm, and hence best classified as AUS. If abundant inflammatory cells are present (e.g., abscess material, granulomatous inflammation), even without an epithelial component, such cases should be interpreted as adequate and non-neoplastic. Also, aspirates with any significant cytologic atypia should not be classified as non-diagnostic. Rather, if scant, but ample well-preserved atypical epithelial cells are identified, a diagnosis of salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP) should be rendered. Cyst contents that contain only scant atypical squamous cells may be signed out as suspicious for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Finally, for non-diagnostic cases or aspirates reported as AUS, repeat FNA under ultrasound guidance should be recommended, especially if there is a clinical or imaging concern for malignancy [21].

Table 3.

The Milan System for reporting salivary gland cytopathology for cystic lesions

| Diagnostic category | Example of cystic salivary gland lesion |

|---|---|

| Non-diagnostic | Cystic non-mucinous fluid only |

| Non-neoplastic | Inflammatory cyst with amylase crystalloids |

| Atypia of undetermined significance | Histiocytes ± scant epithelial cells in a background of abundant mucin (cannot exclude low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma) |

| Benign neoplasm | Warthin tumor, or cystic pleomorphic adenoma |

| Salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP) | Cellular oncocytic/oncocytoid neoplasm with cystic background (differential includes Warthin tumor or oncocytic cystadenoma) |

| Suspicious for malignancy | Atypical cells in a mucinous background, suspicious for low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| Malignant | Keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma |

Differential Diagnosis

There is a broad differential diagnosis to consider when evaluating an FNA specimen obtained from a salivary gland cyst. The diagnostic approach recommended follows the algorithm depicted in Fig. 1.

Mucinous Salivary Gland Cysts

The differential diagnosis of mucin-containing cysts includes non-neoplastic cysts and cystic neoplasms with mucinous features [22].

Non-neoplastic Mucus Cysts

Non-neoplastic cysts that contain mucin include mucus retention cysts and mucoceles. Mucus retention cysts (sialocysts or salivary duct cysts) are common. They frequently develop following salivary gland duct obstruction (e.g., sialolith, inspissated secretion) that results in duct ectasia with focal containment of mucoid material. Mucoceles are pseudocysts associated with mucus extravasation from salivary glands into surrounding soft tissue (Fig. 2). They may occur due to trauma as well as obstruction of salivary gland ducts. Both mucous retention and extravasation cysts mainly arise in minor salivary glands (e.g., buccal mucosa, lip). However, they may occur in major salivary glands (e.g., superficial lobe of the parotid, sublingual gland). A ranula is a large mucocele arising from the sublingual gland that presents in the anterior floor of the mouth (oral ranula) that may subsequently push down into the deep submental space (plunging ranula). Retention cysts tend to occur in the elderly whilst mucoceles are found mostly in children and young adults. Unlike a mucocele that is surrounded by granulation tissue and/or fibrosis, a salivary duct cyst is lined by epithelium (true cyst). They are lined by 1–2 layers of cuboidal/columnar epithelium showing varying types of metaplasia (oncocytic, mucous cell, squamous, sebaceous, ciliated, apocrine-like) [23]. Papillary proliferation may rarely be seen, and should be separated from a cystadenoma [24]. They may occasionally have a ‘Warthin tumor-like’ lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. FNA of these lesions demonstrates hypocellular mucinous material contents, possibly with inflammatory cells and in the case of retention cysts also scant degenerated cuboidal, oncocytic or squamoid epithelial cells [25].

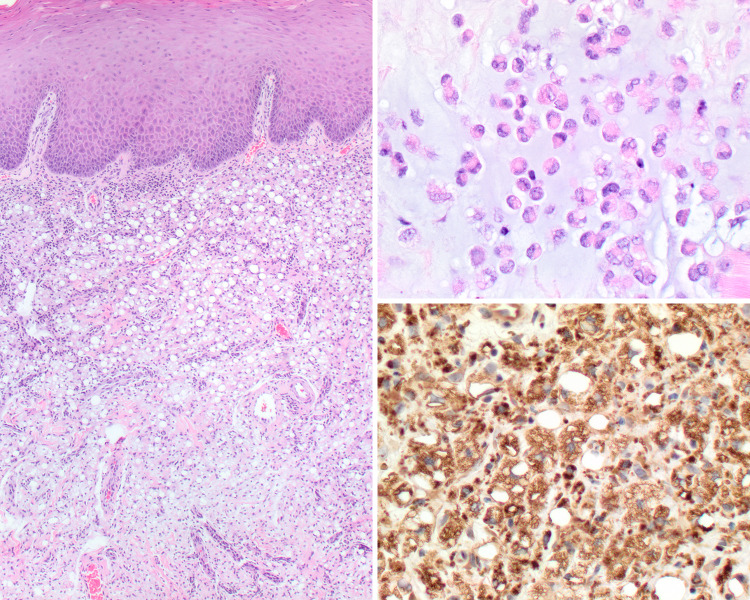

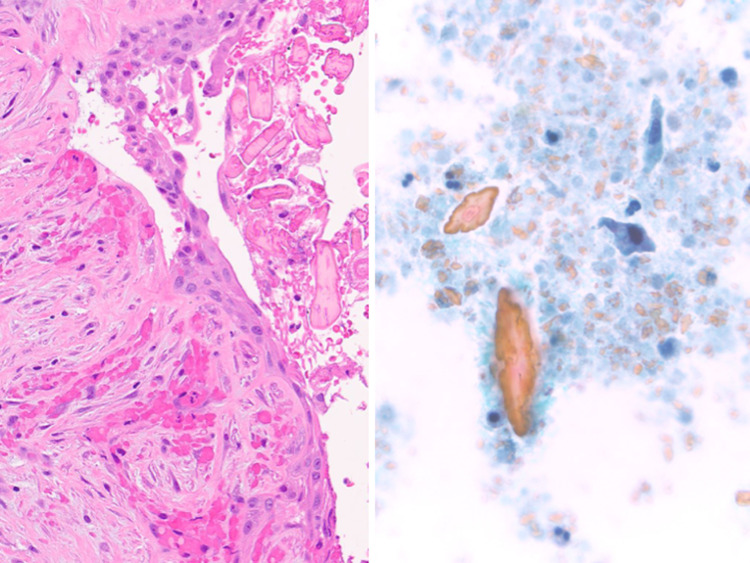

Fig. 2.

Salivary mucocele biopsy showing (left) submucosal mucus extravasation (H&E stain, medium magnification) (upper right) associated with abundant admixed histiocytes (H&E stain, high magnification). (Lower right) Muciphages are CD68 immunoreactive (Immunohistochemistry, high magnification)

Cystic Mucinous Neoplasms

Cystic neoplasms with mucinous features include low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC), papillary cystadenocarcinoma, and Warthin tumor or pleomorphic adenoma with mucinous metaplasia.

MEC is a common primary salivary gland malignancy in young adults and children. They are seen mostly in the parotid gland, but can involve any of the other glands. These tumors are classified into low-, intermediate-, and high-grade carcinomas. By ultrasound, low-grade MEC can mimic a benign, well-defined salivary cyst [26]. They can have cystic (typically with low-grade MEC) and/or solid (typically with higher-grade MEC) components. The amount of mucin aspirated often depends on tumor grade. Failure to obtain diagnostic material may occur with purely cystic tumors and/or if any solid component is not sampled. Low-grade MEC has mostly glandular (mucinous) cells (Fig. 3), that produce abundant mucin, and mixed squamous (epidermoid) cells [27]. They are a common cause of false negative salivary gland diagnoses because aspirates typically yield hypocellular specimens that show predominantly abundant extracellular stringy mucin, few macrophages, and bland epithelial cells (Fig. 4) [25, 28]. Mucinous cells often resemble histiocytes. “Histiocytoid” cells may be round or columnar, have abundant finely vacuolated cytoplasm, and usually contain small uniform eccentrically located nuclei. Such cells are typically immunoreactive for cytokeratin and p63, but are negative for androgen receptor and CD68. Cystic oncocytic MEC with a lymphoid component may mimic Warthin tumor [29]. A Warthin-like MEC variant of mucoepidermoid carcinoma has also been described [30]. In addition, MEC may rarely involve Warthin tumors [31]. In FNA samples obtained from higher-grade MEC, there is increased cellularity, cells with high-grade features (e.g., pleomorphism, high N:C ratio, prominent nucleoli, mitoses) and possibly necrosis. In these aspirates, one is also more likely to find coexistence of mucin-secreting goblet-type cells, polygonal intermediate (clear ductal-appearing) cells, and crowded sheets/clusters of non-keratinizing squamoid cells. Although keratinization is rare, squamoid cells can be mistaken for metaplastic squamous cells or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. For difficult cystic tumors with a high index of suspicion for MEC, repeat aspiration may be helpful. In addition, if there are sufficient cells present, one can attempt to identify a MAML2 rearrangement that is detectable in most (80–85%) MECs.

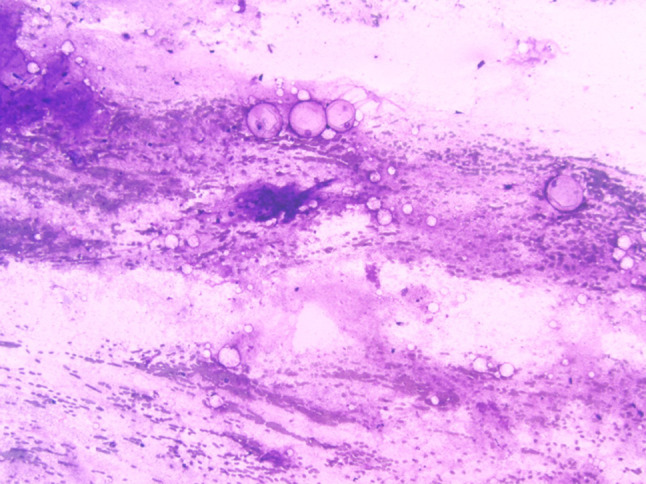

Fig. 3.

Low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma cyst lining showing admixed mucinous and squamous epithelial cells (Mucicarmine stain, magnification × 20)

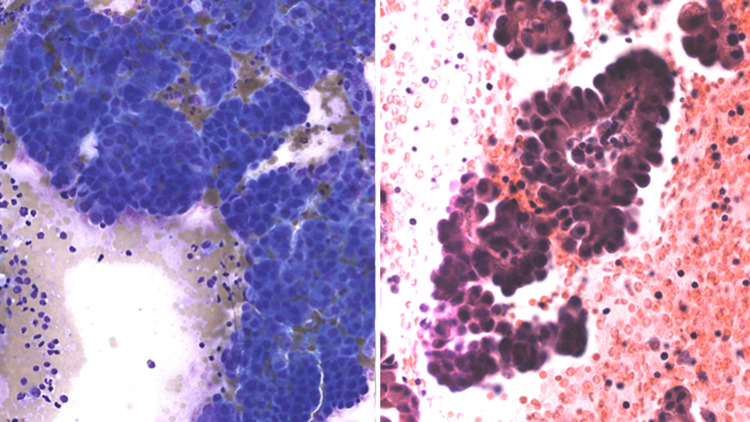

Fig. 4.

FNA of a cystic low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma showing a hypocellular specimen with abundant extracellular mucin and scattered bland histiocytoid cells (Diff Quick stain, magnification × 10)

Cystadenomas are rare, benign, large, well-circumscribed tumors characterized by a unicystic or multicystic growth pattern. They arise most commonly in adult females and involve major or minor salivary glands equally. Unilocular cysts mimic duct ectasia. They may contain focal or abundant intraluminal papillary projections. Their lining epithelium consists of bland cuboidal or columnar cells, which may show oncocytic or less often mucous, apocrine or squamous differentiation [2, 32, 33]. Unlike Warthin tumor, in papillary oncocytic cystadenoma the oncocytic epithelium is unilayered without a bilayered tram-track appearance, lacking a dense lymphoid stroma. These neoplastic cysts may contain crystalloids, calcifications and histiocytes [34]. Cystadenocarcinoma is the malignant counterpart. They are also either unilocular or multicystic but in these tumors the cysts, smaller ducts and solid nests focally infiltrate into the adjacent salivary gland parenchyma. Their lining epithelium has more numerous and complex papillae. A variety of cell types can be seen including mucous, clear, oncocytic and rarely epidermoid cells. Their cyst lumens are filled with mucin and on occasion, dystrophic calcification. The cytological features of these malignancies depend on their grade and histological features. FNA can accordingly show scant vacuolated tumor cell clusters with relatively bland nuclei and background mucinous cystic fluid [35–37], or with higher grade malignancies may be more cellular and contain papillary clusters of glandular cells (Fig. 5). Unlike cystic MEC, these malignancies lack an admixture of both mucous and squamous cells.

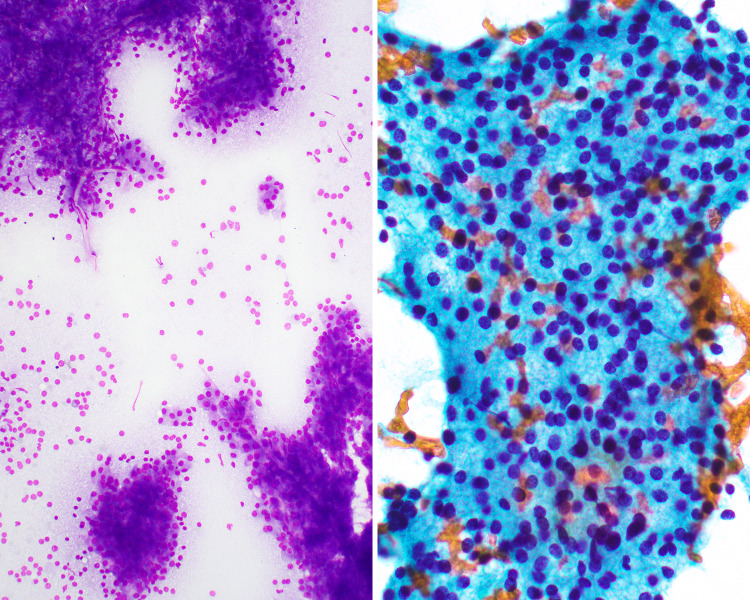

Fig. 5.

FNA of a cystadencarcinoma showing papillary features (left: Diff Quick stain, magnification × 10; right: H&E stain, magnification × 10)

Non-mucinous Salivary Gland Cysts

A practical approach to the differential diagnosis of cystic salivary gland lesions that yield non-mucinous aspirates is to further classify them into samples with and without associated lymphocytes.

Lymphocytic Non-mucinous Salivary Gland Lesions

The differential diagnosis of a cystic, non-mucinous lymphocytic aspirate includes non-neoplastic cysts (e.g., lymphoepithelial cysts) and lymphoid-rich cystic neoplasms (e.g., Warthin tumor).

Non-neoplastic Lymphocytic Cysts

Salivary gland lesions that fall into this category are lymphoepithelial cysts. The term lymphoepithelial cyst (LEC) was introduced in 1958, instead of branchial cleft cyst [38]. LEC may be single (simple) (Fig. 6), but more recently, have been associated with HIV/AIDS [39–41]. HIV-associated LEC usually manifest as multiple, bilateral lesions affecting the parotid glands. They may sometimes be the first manifestation of HIV infection. LEC can also occur in association with chronic infection and autoimmune sialadenitis, most commonly Sjögren syndrome [42]. In Sjögren syndrome, minor salivary glands tend to be involved. LEC are acquired cysts, postulated to either arise from cystic transformation of inclusions within intra-/peri-salivary gland lymph nodes or secondary to obstruction from lymphoid hyperplasia within the salivary gland [43]. They range in size from 0.5 up to 5.0 cm, chiefly involve major salivary glands, and histologically form well-encapsulated cystic lesions associated with reactive (i.e., follicular hyperplasia) lymphoid stroma. LEC can be lined by glandular, pseudostratified squamous or ciliated epithelium. FNA harvests clear-to-turbid fluid that may sometimes be purulent. Cytomorphology shows polymorphous lymphoid cells, foamy histiocytes and a proteinaceous background. There may also be lymphohistiocytic aggregates indicative of germinal centers. HIV-associated LEC may contain numerous large, multinucleated giant cells [44]. Samples lack large sheet-like lymphoepithelial lesions characteristic of autoimmune sialadenitis or marginal-zone lymphoma. LEC may be associated with lymphoma. If there is concern for lymphoma, flow cytometry should be performed. Aspirates obtained from cysts with a squamous lining may show parakeratotic squamous cells with reactive atypia, as well as anucleated squamous cells, keratin debris and cholesterol crystals. However, there should not be significant atypia typically seen with cystic metastatic squamous cell carcinoma.

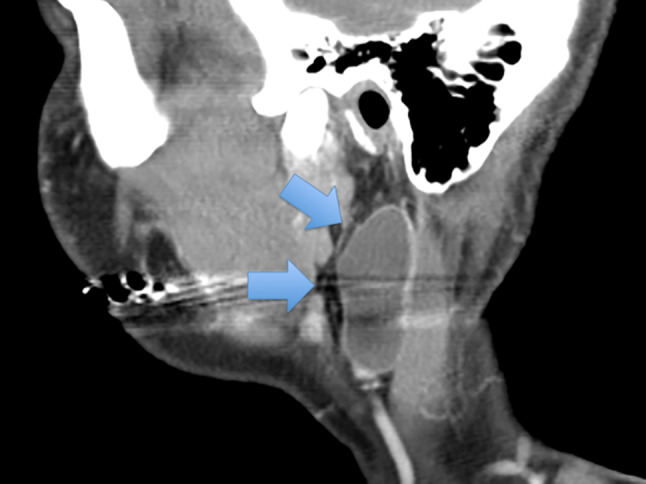

Fig. 6.

CT scan showing a lymphoepithelial cyst (arrows) within the parotid gland

Neoplastic Lymphocytic Cysts

The neoplasm most likely to yield a non-mucinous lymphocytic aspirate is Warthin tumor. Warthin tumor (also known as papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum) almost always occurs within the parotid gland, with exceptional single cases reported in minor salivary glands [45]. Around 10–15% are bilateral, with up to 30% being multifocal [46, 47]. They typically occur in adults, males, and especially smokers. There is a rare increased risk of malignancy, of either epithelial (e.g., MEC) [31] or lymphoid (e.g., lymphoma) [48] origin. Aspirates grossly resemble “machine oil” (i.e. thin, oily, and yellow-tan appearance). The characteristic microscopic finding is oncocytic epithelial cells forming 2D sheets or papillary-like clusters associated with polymorphous lymphocytes (Figs. 7, 8). The oncocytic cells have abundant granular cytoplasm, round nuclei, and nucleoli. The cystic background has “dirty” appearing proteinaceous material with histiocytes, sometimes cholesterol crystals, inflammatory cells and debris. Some Warthin tumors can have squamous metaplasia which may yield atypical squamous cells, making it possible to misdiagnose them as squamous cell carcinoma [49–51]. There may infrequently also be mucinous metaplasia, which raises the consideration of a MEC.

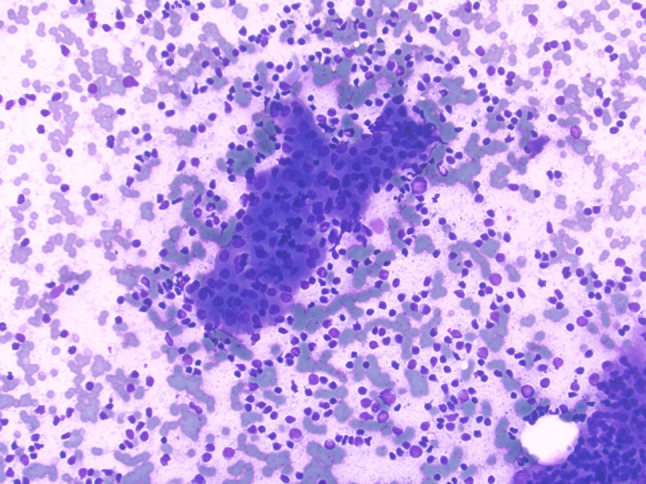

Fig. 7.

FNA smear procured from a Warthin tumor showing a sheet of oncocytic epithelial cells associated with background polymorphous lymphocytes (Diff Quick stain, magnification × 20)

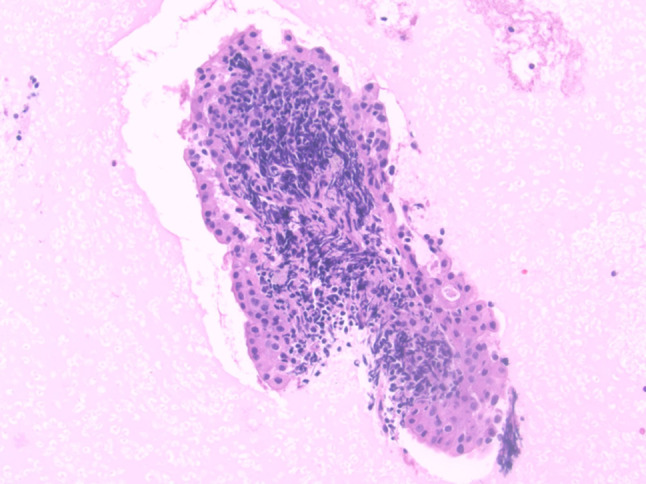

Fig. 8.

Cell block specimen showing a papillary fragment of a Warthin tumor with characteristic bilayered oncocytic epithelium and lymphoid-rich stroma (H&E stain, magnification × 20)

Non-lymphocytic, Non-mucinous Salivary Gland Lesions

The differential diagnosis of salivary gland cysts with non-mucinous and non-lymphocytic cyst contents includes non-neoplastic cysts (e.g., polycystic disease and inflammatory cysts) and a diverse group of neoplasms with cystic change (e.g., acinic cell carcinoma, pleomorphic adenoma, etc.).

Non-neoplastic, Non-lymphocytic, Non-mucinous Cysts

Polycystic (dysgenetic) disease is a rare congenital cause of cystic change in the salivary glands [52, 53]. In most cases both parotid glands are affected, particularly in women. Minor salivary gland involvement is unusual [54]. This condition is not associated with polycystic disease affecting other organs. With this disease, salivary gland parenchyma is gradually replaced by multiple, fluctuating honeycombed epithelial-lined cystic spaces of variable size. Their cyst lining can be glandular (apocrine-like) or squamous, but there is no associated dense fibrosis. Cysts may contain microliths. Aspirates demonstrate scant bland epithelial cells and cyst contents devoid of mucin or lymphocytes [55].

Infected cysts can have numerous admixed neutrophils and possibly even scattered bacteria (Fig. 9). Other salivary gland cysts that belong to this non-neoplastic category are the benign inflammatory cysts associated with chronic sialadenitis, duct obstruction (sialolithiasis) and duct ectasia. Unlike the aforementioned developmental cysts, these cysts may contain α-amylase crystalloids, stone fragments, as well as acute and/or chronic inflammation. Aspirates therefore yield gritty, turbid or even purulent material (Fig. 10). Amylase crystalloids are non-birefringent multifaceted structures with rectangular, rhomboid, and/or needle-like shapes (Fig. 11). The majority of them are extracellular, but they may also be identified within histiocytes and giant cells. The crystalloids are believed to arise from saturated saliva. Crystalloids readily fragment in aspirates and for this reason may be easily overlooked as background debris. Such amylase crystalloids are typically associated with non-neoplastic inflammatory conditions (e.g., sialadenitis), but have also rarely been reported in association with Warthin tumor and pleomorphic adenoma (Table 4) [56–59]. Amylase crystalloids need to be differentiated from floret-shaped tyrosine crystalloids. Tyrosine crystalloids are more common in black patients and often associated with neoplasms such as pleomorphic adenoma [60–62]. Injury or rupture of an inflammatory cyst may spill amylase crystalloids, which may in turn induce a foreign body reaction with multinucleated giant cells resulting in an “amylase crystalloid granuloma” (Fig. 12) [59, 63–67]. Based on data from limited case reports published to date, amylase granulomas present predominantly in the parotid gland (the main source of α-amylase) in patients over 60 years of age. Their size ranges from 1 to 6 cm [59]. The crystalloids are immunoreactive with an α-amylase immunohistochemical stain. The epithelium of inflammatory cysts may be denuded, flattened or lined by squamous (Fig. 13), mucinous or ciliated metaplasia. Whilst a cystic squamous cell carcinoma may be of diagnostic concern in cases that demonstrate reactive squamous atypia, carcinoma is typically not associated with amylase crystalloids.

Fig. 9.

FNA procured from an infected inflammatory cyst showing amylase crystals present among abundant acute inflammatory cells and scattered bacterial cocci (Gram stain, magnification × 60)

Fig. 10.

Purulent appearing material aspirated from an inflammatory salivary gland cyst

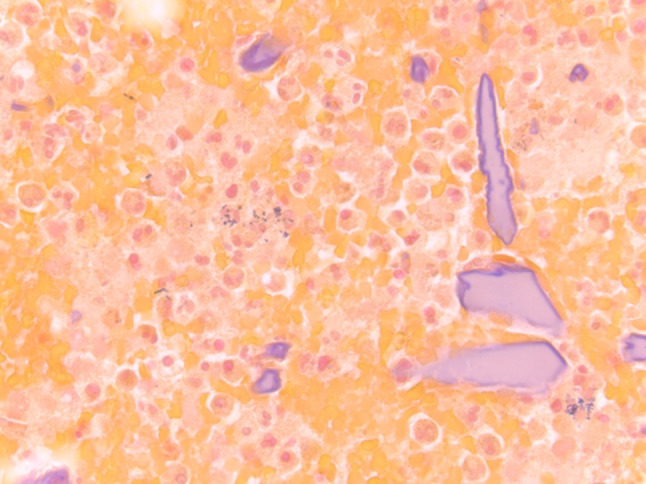

Fig. 11.

a Amylase crystalloids in a FNA smear (Diff Quick stain, magnification × 20). b Fragmented amylase crystalloids shown in a FNA cell block (H&E stain, magnification × 20)

Table 4.

Characteristics of salivary gland crystalloids seen in aspirates

(adapted from Kuwabara et al. [57])

| Crystalloid | Size (microns) | Shape | Stain appearance | Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | 5–200 | Rectangular, rhomboid, rods, and/or needle-like | Blue with DQ stain, orange with Papanicolaou stain, pink-red with H&E | Benign inflammatory cyst, sialadenitis, amylase crystalloid granuloma, sialolithiasis, and rarely cystadenoma, Warthin tumor or pleomorphic adenoma |

| Tyrosine | 30–60 | Floret-shaped | Blue-black with DQ stain, yellow-orange with Papanicolaou stain, pink with H&E | Mostly pleomorphic adenoma, oncocytic cysts, sometimes polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma or adenoid cystic carcinoma |

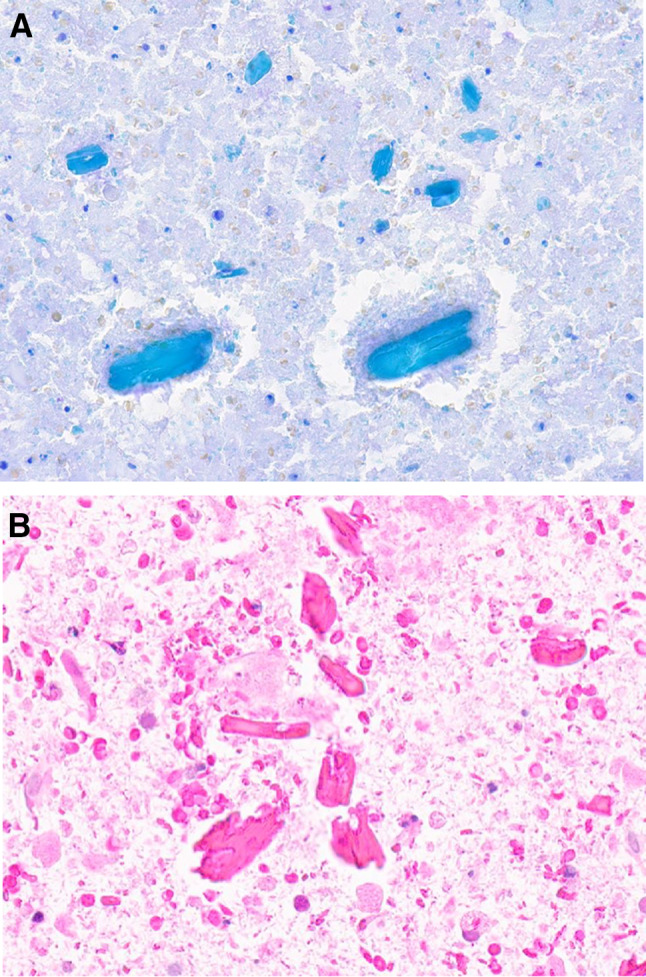

Fig. 12.

Amylase crystalloid granuloma. (Left) Inflammatory cyst associated with a marked peripheral foreign body reaction to crystalloids (H&E stain, magnification × 10). (Right) Numerous eosinophilic amylase crystalloids are shown mixed with histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells (H&E stain, magnification × 40)

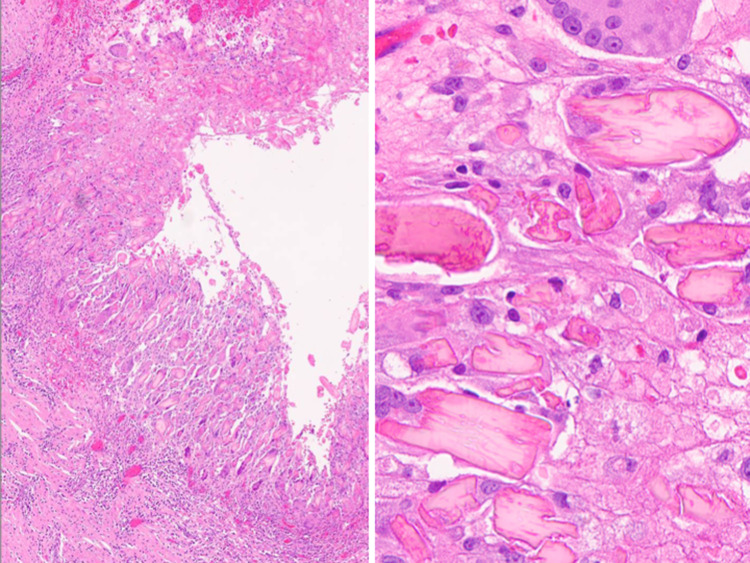

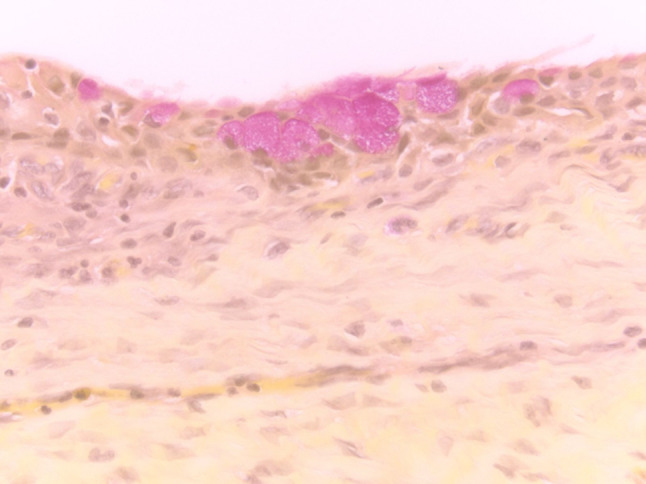

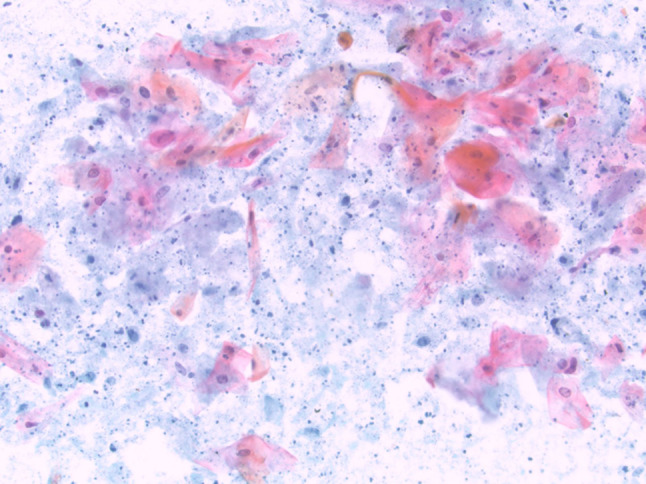

Fig. 13.

(Left) Inflammatory cyst lined by squamous metaplasia (H&E stain, magnification × 40). (Right) FNA of cyst contents from an inflammatory cyst containing scattered atypical metaplastic squamous cells, scant inflammatory cells and numerous orangeophilic crystalloids (Papanicolaou stain, magnification × 60)

Neoplastic Non-lymphocytic, Non-mucinous Cysts

In addition to the aforementioned tumors, several other salivary gland neoplasms can also rarely present with a predominant or partially cystic component. They include basal cell adenoma, canalicular adenoma, oncocytoma, sebaceous adenoma, intraductal papilloma, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, intraductal carcinoma, and secretory carcinoma [2]. Furthermore, some primarily solid tumors can also undergo cystic degeneration with necrosis. FNA of these variants may yield only hypocellular fluid, making them hard to diagnose. Hence, it is important to ensure that diagnostic material in such cases also be obtained from any solid portion of these cystic tumors.

Pleomorphic adenoma, the most common salivary gland neoplasm, can sometimes contain cysts [2]. Smaller cysts are frequently lined by squamous epithelium and they may contain keratin. Larger cysts, typically due to cystic degeneration, have no true epithelial lining but are instead lined by a rim of mixed tumor elements typical of solid pleomorphic adenomas. In aspirated material, there may be non-mucinous cyst contents associated with metaplastic epithelium and possibly fragments of epithelial and myoepithelial cells embedded within chondromyxoid stroma. Cytologic atypia may be observed with metaplastic squamous changes [25]. In such cases, an atypical diagnosis should be rendered, with a comment about excluding a malignancy (such as MEC).

Secretory carcinoma (formerly called mammary analogue secretory carcinoma) is a relatively recently characterized low-grade salivary gland carcinoma harboring the unique translocation t(12;15)(p13;q25) that results in an ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion [68]. These tumors typically arise in adults, and mostly within the parotid gland. They occasionally form cysts filled with white fluid. The cytological diagnosis of secretory carcinoma is difficult [69–72]. FNA may show cohesive epithelial clusters, sheets, papillary groups and/or dispersed cells with background colloid-like cystic debris. The epithelial cells have abundant granular, vacuolated (histiocyte-like) or clear cytoplasm, round nuclei, and sometimes prominent nucleoli (Fig. 14). Nuclear membrane irregularities, nuclear grooves, and hyalinized tissue fragments can be identified in cell block material [73]. The cells may have positive intracellular mucin staining, mimicking low-grade MEC [74]. Histologically secretory carcinomas may demonstrate a solid, microcystic, tubular, follicular and/or papillary-cystic growth pattern. They are S100 and mammaglobin positive [75].

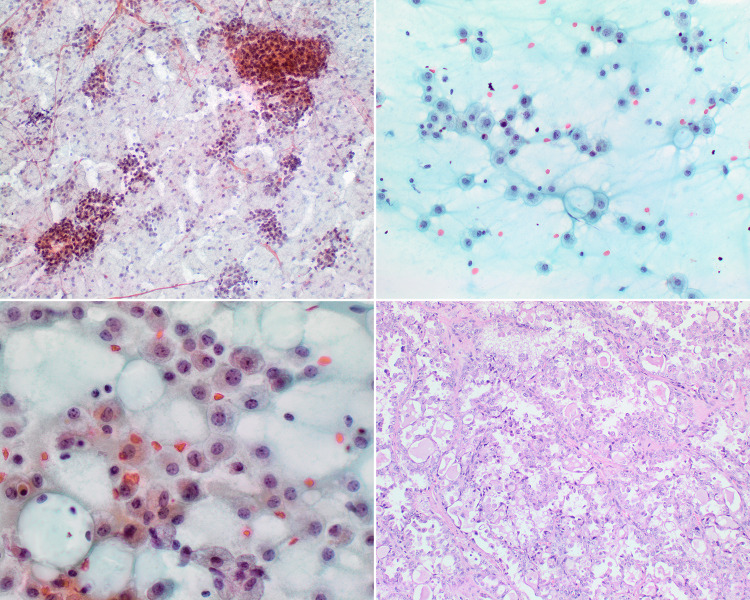

Fig. 14.

Secretory carcinoma. (Upper left) FNA showing cohesive epithelial clusters and dispersed cells associated with background proteinaceous cyst material (Papanicolaou stain, magnification × 10). (Upper right and lower left) Dyshesive histiocyte-like epithelial cells are shown with bland nuclear features and background mucin (Papanicolaou stain, magnification × 40). (Lower right) Tumor showing a papillary-microcystic growth pattern. Note the homogeneous colloid-like luminal secretion (H&E stain, magnification × 20)

Acinic cell carcinoma (AcCC) is another generally low-grade malignancy that mostly occurs in the parotid gland of patients around 50 years of age. AcCC varies from being solid to cystic. AcCC with a microcystic growth pattern has many variably sized spaces (microns to millimeters) that contain amorphous non-mucinous proteinaceous material [2]. Lymphocytes and lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers may be seen in up to 30% of cases. Unlike secretory carcinoma, they are mammaglobin negative. The papillary cystic variant of AcCC (AcCC-PCV) presents in younger female patients (16–40 years) and portends a poor prognosis. These tumors have much larger cysts (macrocysts) filled with papillary epithelial proliferations. FNA specimens are accordingly more cellular and contain papillary clusters made up of several cells including ductal, histiocyte-like vacuolated and/or acinar granular type cells (Fig. 15) [76–80]. AcCC-PCV may undergo metaplastic oncocytic or squamoid changes [72]. Some macrocysts may even contain scant mucin [2]. Given this variegated appearance, the cytological diagnosis of AcCC-PCV is understandably difficult. Of note, nearly all of these tumors can probably be reclassified as secretory carcinoma [81].

Fig. 15.

FNA showing (left) papillary clusters (Diff Quick stain, magnification × 20) and (right) a sheet of serous acinar cells (Papanicolaou stain, magnification × 40) characteristic of acinic cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma rarely develops as a primary salivary gland neoplasm, but is much more common as a metastatic lesion to intra- or peri-glandular lymph nodes. These metastases frequently undergo cystic change. FNA findings include atypical squamous cells, sometimes with keratin debris (Fig. 16) [82]. Cases with scant viable cellularity, limited atypia, and/or extensive necrosis are best classified as atypical. Squamous cell carcinoma needs to be distinguished from an epidermal inclusion cyst, lymphoepithelial cyst with reactive squamous metaplasia, and MEC. Compared to MEC, squamous cell carcinoma lacks extracellular and/or intracellular mucin.

Fig. 16.

FNA from a cystic squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the salivary gland showing keratinized squamous cells with only mild atypia present in a background of cystic debris (Papanicolaou stain, magnification × 20)

Conclusion

FNA is of diagnostic and sometimes therapeutic value when managing a patient with one or multiple salivary gland cysts. FNA in this context has low sensitivity, but good specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value for detecting neoplasms. The challenge in rendering an accurate diagnosis is related to the broad differential diagnosis, sampling error, frequent hypocellularity of specimens, and morphologic heterogeneity of some lesions. Moreover, there is often overlapping cytomorphology with many of the cystic entities. For example, squamous cells and mucin may not only be identified in cystic neoplasms such as MEC with admixed epidermoid and mucous-producing cells, but is also identified in aspirates from benign inflammatory cysts lined by epithelium with squamous and mucinous metaplasia. Similarly, sebocyte-like cells have been described in both cystic sebaceous lymphadenoma [83] and sclerosing polycystic adenosis [84]. Even the finding of amylase crystalloids may be associated with both non-neoplastic and rarely, neoplastic lesions. Reliable interpretation thus depends on correlation of cytologic findings with pertinent clinical and radiographic information. Separating FNA specimens based upon the presence of mucin and admixed lymphocytes in cyst fluid is helpful in the evaluation these cases. For indeterminate cases, The Milan System for reporting salivary gland cytopathology provides useful criteria for acellular aspirates derived from cystic non-mucinous lesions (i.e., classified as non-diagnostic) and those containing mucinous material but with only scant epithelial cells (i.e. classified as atypia of undetermined significance). Evaluation of the literature regarding salivary gland cysts is challenging given the change in terminology for several of these cystic entities (e.g., lymphoepithelial cyst and formerly branchial cleft cyst). Also, further studies are required to determine the feasibility of employing newer ancillary studies to evaluate hypocellular cyst samples. Nevertheless, FNA remains a useful procedure early on in the diagnostic work-up of patients with cystic salivary gland lesions since it can help reduce the number of patients requiring surgery.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Takita H, Takeshita T, Shimono T, Tanaka H, Iguchi H, Hashimoto S, Kuwae Y, Ohsawa M, Miki Y. Cystic lesions of the parotid gland: radiologic-pathologic correlation according to the latest World Health Organization 2017 Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35:629–647. doi: 10.1007/s11604-017-0678-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis GL, Auclair PL. Tumors of the salivary glands. Washington DC: ARP Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pusztaszeri M, Baloch Z, Faquin WC, Rossi ED, Tabatabai ZL. Atypia of undetermined significance. In: Faquin WC, Rossi ED, editors. The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. Cham: Springer; 2018. pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenig BM. Atlas of head and neck pathology. 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegde PN, Prasad HLK, Kumar YS, Sajitha K, Roy PS, Raju M, Shetty V. A rare case of an epidermoid cyst in the parotid gland: which was diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:550–552. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4857.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Li Y, Tang Y. Keratocystoma of the parotid gland: a case report and review of previous publications. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:655–657. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Righi PD, Wells WA, Wagner JD, Kim SA, Anderson MW, Longardner NR. Odontogenic keratocyst of the mandible: an unusual cause of a parotid mass. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41:89–93. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199807000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora VK, Chopra N, Singh P, Venugopal VK, Narang S. Hydatid cyst of parotid: report of unusual cytological findings extending the cytomorphological spectrum. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:770–773. doi: 10.1002/dc.23515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Białek EW, Jakubowski W. Mistakes in ultrasound examination of salivary glands. J Ultrasonography. 2016;16:191–203. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2016.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Layfield L. Cytopathology of the head and neck. Chicago: ASCP Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firat P, Ersoz C, Uguz A, Onder S. Cystic lesions of the head and neck: cytohistological correlation in 63 cases. Cytopathology. 2007;18:184–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KT. Diagnostic pitfalls in fine needle aspiration of cystic salivary gland lesions. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:675–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MW, Kim DW, Jung HS, Choo HJ, Park YM, Jung SJ, Baek HJ. Factors influencing the outcome of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for salivary gland lesion diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:877–883. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.06062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart CJ, MacKenzie K, McGarry GW, Mowat A. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland: a review of 341 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:139–146. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(20000301)22:3<139::AID-DC2>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Layfield LJ, Gopez EV. Cystic lesions of the salivary glands: cytologic features in fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:197–204. doi: 10.1002/dc.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards PC, Wasserman P. Evaluation of cystic salivary gland lesions by fine needle aspiration: an analysis of 21 cases. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:489–494. doi: 10.1159/000326193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allison DB, Mc Cuiston AM, Kawamoto S, Eisele DW, Bishop JA, Maleki Z. Cystic salivary gland lesions: utilizing fine needle aspiration to optimize the clinical management of a broad and diverse differential diagnoses. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:800–807. doi: 10.1002/dc.23780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madrigal E, Chhieng D, Harshan M. Cytologic-histologic correlation of cystic non-mucinous and mucinous salivary gland lesions. J of Am Soc Cytopathol. 2017;6:S82. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2017.06.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baloch Z, Field AS, Katabi N, Wenig BM. The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. In: Faquin WC, Rossi ED, editors. The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. Cham: Springer; 2018. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moatamed NA, Naini BV, Fathizadeh P, Estrella J, Apple SK. A correlation study of diagnostic fine-needle aspiration with histologic diagnosis in cystic neck lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:720–726. doi: 10.1002/dc.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bajwa MS, Nicolai P, Varvares MA. Clinical management. In: Faquin WC, Rossi ED, editors. The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. Cham: Springer; 2018. pp. 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faquin WC, Powers CN. Cystic and mucinous lesions: mucocele and low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. In: Faquin WC, Powers CN, editors. Salivary gland cytopathology. Boston: Springer; 2008. p. 159181. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stojanov IJ, Malik UA, Woo SB. Intraoral salivary duct cyst: clinical and histopathologic features of 177 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:469–476. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0810-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Brito Monteiro BV, Bezerra TM, da Silveira ÉJ, Nonaka CF, da Costa Miguel MC. Histopathological review of 667 cases of oral mucoceles with emphasis on uncommon histopathological variations. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2016;21:44–46. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalbuss WE, Monaco SE, Pantanowitz L. Quick compendium of cytopathology. Chicago: ASCP Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong X, Xiong P, Liu S, Xu Q, Chen Y. Ultrasonographic appearances of mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the salivary glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elsheikh TM, Chute DJ. Tumors of the salivary glands: benign and low-grade malignancies. In: Baloch ZW, Elsheikh TM, Faquin WC, Vielh P, editors. Head and neck cytohistology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. pp. 76–109. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph TP, Joseph CP, Jayalakshmy PS, Poothiode U. Diagnostic challenges in cytology of mucoepidermoid carcinoma: report of 6 cases with histopathological correlation. J Cytol. 2015;32:21–24. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.155226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wade TV, Livolsi VA, Montone KT, Baloch ZW. A correlation of mucoepidermoid carcinoma: emphasizing the rare oncocytic variant. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:135796. doi: 10.4061/2011/135796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hang JF, Shum CH, Ali SZ, Bishop JA. Cytological features of the Warthin-like variant of salivary mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:1132–1136. doi: 10.1002/dc.23785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson JD, Simmons BH, el-Naggar A, Medeiros LJ. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma involving Warthin tumor. A report of five cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:564–570. doi: 10.1309/GUT1-F58A-V4WV-0D8P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chin S, Kim HK, Kwak JJ. Oncocytic papillary cystadenoma of major salivary glands: three rare cases with diverse cytologic features. J Cytol. 2014;31:221–223. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.151140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budnick S, Simpson RHW. Cystadenoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumors. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Başak K, Kiroğlu K. Multiple oncocytic cystadenoma with intraluminal crystalloids in parotid gland: case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e246. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawahara A, Harada H, Mihashi H, Akiba J, Kage M. Cytological features of cystadenocarcinoma in cyst fluid of the parotid gland: diagnostic pitfalls and literature review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:377–381. doi: 10.1002/dc.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khatib Y, Dande M, Patel RD, Kane SV. Cytomorphological findings and histological correlation of papillary cystadenocarcinoma of the parotid: not always a low-grade tumor. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2016;59:368–371. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.188114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneller J, Solomon M, Webber CA, Nasim M. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the parotid gland: report of a case with fine needle aspiration findings and histologic correlation. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:605–609. doi: 10.1159/000327872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernier JL, Bhaskar SN. Lymphoepithelial lesions of salivary glands; histogenesis and classification based on 186 cases. Cancer. 1958;11:1156–1179. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195811/12)11:6<1156::AID-CNCR2820110611>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Upile T, Jerjes W, Al-Khawalde M, Kafas P, Frampton S, Gray A, Addis B, Sandison A, Patel N, Sudhoff H, Radhi H. Branchial cysts within the parotid salivary gland. Head Neck Oncol. 2012;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michelow P, Dezube BJ, Pantanowitz L. Fine needle aspiration of salivary gland masses in HIV-infected patients. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:684–690. doi: 10.1002/dc.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahamed AS, Kannan VS, Velaven K, Sathyanarayanan GR, Roshni J, Elavarasi E. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the submandibular gland. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6(Suppl 1):S185–S187. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.137464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gadodia A, Seith A, Sharma R. Unusual presentation of Sjögren syndrome: multiple parotid cysts. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012;91:E17–E19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu L, Cheng J, Maruyama S, Yamazaki M, Tsuneki M, Lu Y, He Z, Zheng Y, Zhou Z, Saku T. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the parotid gland: its possible histopathogenesis based on clinicopathologic analysis of 64 cases. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta N, Gupta R, Rajwanshi A, Bakshi J. Multinucleated giant cells in HIV-associated benign lymphoepithelial cyst-like lesions of the parotid gland on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:203–204. doi: 10.1002/dc.20991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwai T, Baba J, Murata S, Mitsudo K, Maegawa J, Nagahama K, Tohnai I. Warthin tumor arising from the minor salivary gland. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e374–e376. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318254359f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel DK, Morton RP. Demographics of benign parotid tumours: Warthin’s tumour versus other benign salivary tumours. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136:83–86. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1081276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sagiv D, Witt RL, Glikson E, Mansour J, Shalmon B, Yakirevitch A, Wolf M, Alon EE, Slonimsky G, Talmi YP. Warthin tumor within the superficial lobe of the parotid gland: a suggested criterion for diagnosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:1993–1996. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Medeiros LJ, Rizzi R, Lardelli P, Jaffe ES. Malignant lymphoma involving a Warthin’s tumor: a case with immunophenotypic and gene rearrangement analysis. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:974–977. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ballo MS, Shin HJ, Sneige N. Sources of diagnostic error in the fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of Warthin’s tumor and clues to a correct diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;17:230–234. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199709)17:3<230::AID-DC12>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parwani AV, Ali SZ. Diagnostic accuracy and pitfalls in fine-needle aspiration interpretation of Warthin tumor. Cancer. 2003;99:166–171. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viguer JM, Vicandi B, Jiménez-Heffernan JA, López-Ferrer P, González-Peramato P, Castillo C. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis and management of Warthin’s tumour of the salivary glands. Cytopathology. 2010;21:164–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2009.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seifert G, Thomsen S, Donath K. Bilateral dysgenetic polycystic parotid glands. Morphological analysis and differential diagnosis of a rare disease of the salivary glands. Virchows Arch A. 1981;390:273–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00496559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar KA, Mahadesh J, Setty S. Dysgenetic polycystic disease of the parotid gland: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17:248–252. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.119744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koudounarakis E, Willems S, Karakullukcu B. Dysgenetic polycystic disease of the minor and submandibular salivary glands. Head Neck. 2016;38:E2437–E2439. doi: 10.1002/hed.24401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Layfield LJ, Gopez EV. Histologic and fine-needle aspiration cytologic features of polycystic disease of the parotid glands: case report and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:324–328. doi: 10.1002/dc.10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Granter SR, Renshaw AA, Cibas ES. Nontyrosine crystalloids in fine-needle aspiration specimens of the parotid gland: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20:44–46. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199901)20:1<44::AID-DC10>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nasuti JF, Gupta PK, Fleisher SR, LiVolsi VA. Nontyrosine crystalloids in salivary gland lesions: report of seven cases with fine-needle aspiration cytology and follow-up surgical pathology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:167–171. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(20000301)22:3<167::AID-DC7>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pantanowitz L, Goulart RA, Cao QJ. Salivary gland crystalloids. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:749–750. doi: 10.1002/dc.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuwabara H, Ishizaki S, Akashi S, Yuki M, Shibayama Y. α-Amylase crystalloid granuloma in the parotid gland. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:114–116. doi: 10.1002/dc.23119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gould AR, Van Arsdall LR, Hinkle SJ, Harris WR. Tyrosine-rich crystalloids in adenoid cystic carcinoma: histochemical and ultrastructural observations. J Oral Pathol. 1983;12:478–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1983.tb00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raubenheimer EJ, van Heerden WF, Thein T. Tyrosine-rich crystalloids in a polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:480–482. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90215-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lemos LB, Baliga M, Brister T, Cason Z. Cytomorphology of tyrosine-rich crystalloids in fine needle aspirates of salivary gland adenomas. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:1709–1713. doi: 10.1159/000333173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takeda Y. Crystalloid granuloma of the parotid gland: a previously undescribed salivary gland lesion. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20:234–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Horie Y, Ikawa S, Ishizu Y. Crystalloid granuloma of the parotid gland: a case report. Pathol Int. 1994;44:535–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1994.tb02604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yada N, Kashima K, Daa T, Urabe S, Kondo Y, Yokoyama S. α-Amylase crystalloid granuloma of the parotid gland: case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:e43–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho C, Sasaki CT, Prasad ML. Crystalloid granulomas of the parotid gland mimicking tumor: a case report with review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2013;21:282–286. doi: 10.1177/1066896912462128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Srivastava S, Chougule A, Gupta N, Srinivasan R. Crystalloid granuloma with amylase crystalloids in submandibular gland cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:66–67. doi: 10.1002/dc.23384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Skalova A, Bell D, Bishop JA, Inagaki H, Seethala R, Vielh P. Secretory carcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumors. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. pp. 177–178. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bishop JA, Yonescu R, Batista DA, Westra WH, Ali SZ. Cytopathologic features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:228–233. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Samulski TD, LiVolsi VA, Baloch Z. The cytopathologic features of mammary analog secretory carcinoma and its mimics. Cytojournal. 2014;11:24. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.139726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Griffith CC, Stelow EB, Saqi A, Khalbuss WE, Schneider F, Chiosea SI, Seethala RR. The cytological features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: a series of 6 molecularly confirmed cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:234–241. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kai K, Minesaki A, Suzuki K, Monji M, Nakamura M, Tsugitomi H, Kuratomi Y, Aishima S. Difficulty in the cytodiagnosis of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: survey of 109 cytologists with a case originating from a minor salivary gland. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:469–476. doi: 10.1159/000477390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gonzalez MF, Akhtar I, Manucha V. Additional diagnostic features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma on cytology. Cytopathology. 2018;29:100–103. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bajaj J, Gimenez C, Slim F, Aziz M, Das K. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of mammary analog secretory carcinoma masquerading as low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma: case report with a review of the literature. Acta Cytol. 2014;58:501–510. doi: 10.1159/000368070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oza N, Sanghvi K, Shet T, Patil A, Menon S, Ramadwar M, Kane S. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of parotid: Is preoperative cytological diagnosis possible? Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:519–525. doi: 10.1002/dc.23459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ali SZ. Acinic-cell carcinoma, papillary-cystic variant: a diagnostic dilemma in salivary gland aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:244–250. doi: 10.1002/dc.10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shet T, Ghodke R, Kane S, Chinoy RN. Cytomorphologic patterns in papillary cystic variant of acinic cell carcinoma of the salivary gland. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:388–392. doi: 10.1159/000325978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mosunjac MB, Siddiqui MT, Tadros T. Acinic cell carcinoma-papillary cystic variant. Pitfalls of fine needle aspiration diagnosis: Study of five cases and review of literature. Cytopathology. 2009;20:96–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumar U. Acinic cell carcinoma papillary-cystic variant: diagnostic pitfalls in fine needle aspiration cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:ED05–ED6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/21347.9772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jayaram G, Othman MA, Kumar M, Krishnan G. Papillary cystic type of acinic cell carcinoma of parotid: fine needle aspiration cytological features of a high grade variant with oncocytic metaplasia. Malays J Pathol. 2002;24:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Said-Al-Naief N, Carlos R, Vance GH, Miller C, Edwards PC. Combined DOG1 and mammaglobin immunohistochemistry is comparable to ETV6-breakapart analysis for differentiating between papillary cystic variants of acinic cell carcinoma and mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:127–140. doi: 10.1177/1066896916670005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Al-Abbadi M. Metastases and rare primary neoplasms of salivary glands. In: Al-Abbadi M, editor. Salivary gland cytology. A color atlas. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011. pp. 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Squillaci S, Marchione R, Piccolomini M. Cystic sebaceous lymphadenoma of the parotid gland: case report and review of the literature. Pathologica. 2011;103:32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shilpi, Ahmad Ansari F, Bahadur S, Katyal A, Narula A, Nargotra N, Singh S. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis: a rare tumor misdiagnosed as retention cyst on fine needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:640–644. doi: 10.1002/dc.23701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]