Abstract

This clinicopathologic study of primary oral leiomyosarcoma of the buccal mucosa involves a literature review of 15 cases with the addition of our report of a case. The demographic details, tumor size, treatment and outcome are documented for all the cases. In addition, this review examines the histologic features of leiomyosarcoma while noting that differentiation from other spindle cell tumors can be challenging, underscoring the necessity of an immunohistochemical work up for an accurate diagnosis. The unpredictability of the clinical behavior of these aggressive tumors requires, at the very least, wide local surgical excision and prolonged follow up.

Keywords: Leiomyosarcoma, Oral cavity, Head and neck

Introduction

Leiomyosarcoma is a malignant tumor with smooth muscle differentiation and accounts for 5–10% of all soft-tissue sarcomas. It occurs most frequently in the retroperitoneum, and is exceedingly rare in the oral cavity [1, 2]. One explanation for the rarity of leiomyosarcomas in the oral cavity is attributed to the relative paucity of smooth muscles in that region [3–5]. Leiomyosarcomas that occur in the jawbones and oral tissues are thought to arise from the tunica media of blood vessels, erectores pilorum, circumvallate papillae, or from pluripotential mesenchymal cells [5]. Histopathologically, leiomyosarcomas typically present with interlacing fascicles of spindle cells, and so immunohistochemical discrimination of smooth muscle differentiation is often useful to help distinguish leiomyosarcomas from other tumors with similar light microscopic features. In part because of their rarity, leiomyosarcomas can be easily mistaken for other more common spindle cell lesions in the oral cavity [6].

Case Report

An 86-year old male presented to his oral surgeon with a swelling on his right posterior buccal mucosa, which had been unresponsive to antibiotics. An ulcerated area adjacent to tooth #1 was apparent. Subsequent incisional biopsy revealed an initial histopathologic diagnosis of a traumatic ulceration. However, a month later, the patient returned to the oral surgeon due to an increasing ulceration of the right buccal mucosa, and a re-biopsy was performed. No details regarding the size of the lesion nor radiographic images could be obtained from the oral surgeon. Microscopic examination revealed an infiltrative spindle cell neoplasm predominantly arranged in long fascicles and comprised of cells with abundant eosinophilic fibrillary cytoplasm and oval nuclei (see Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Perinuclear vacuoles were present and there were scattered cells with marked cytologic atypia. No necrosis was present but mitotic figures were frequent (5–6 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields). Immunohistochemical stains confirmed the morphologic impression of leiomyosarcoma as the neoplastic cells were diffusely and strongly positive for cytoplasmic expression of desmin, muscle specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Unfortunately, attempts to discover information on treatment and follow up with the patient were unsuccessful.

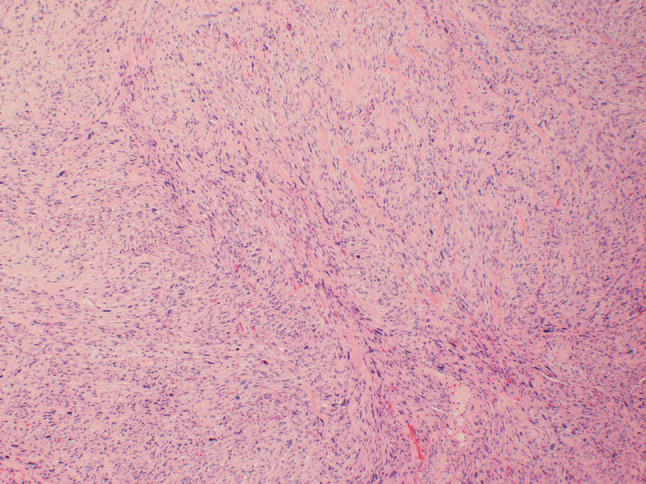

Fig. 1.

At low power (×40), the tumor is comprised of spindle cells arranged in long fascicles. Scattered cells with marked nuclear atypia are present

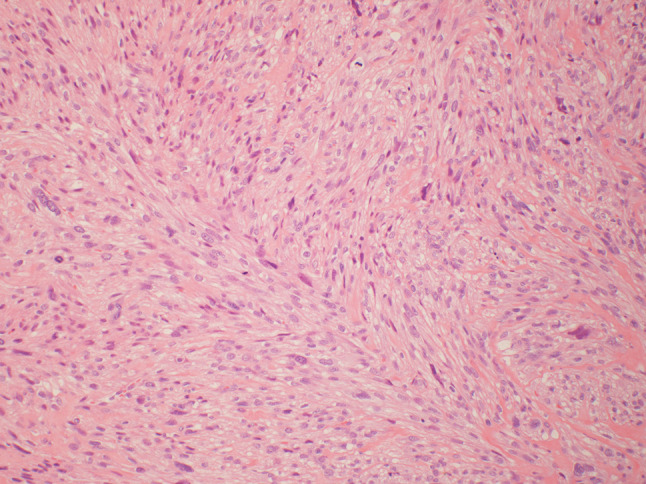

Fig. 2.

At medium power (×100), the spindle cells are arranged in fascicles and contain abundant fibrillary eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei tend to be oval with perinuclear vacuoles. Mitotic figures are common as are scattered cells with marked nuclear atypia

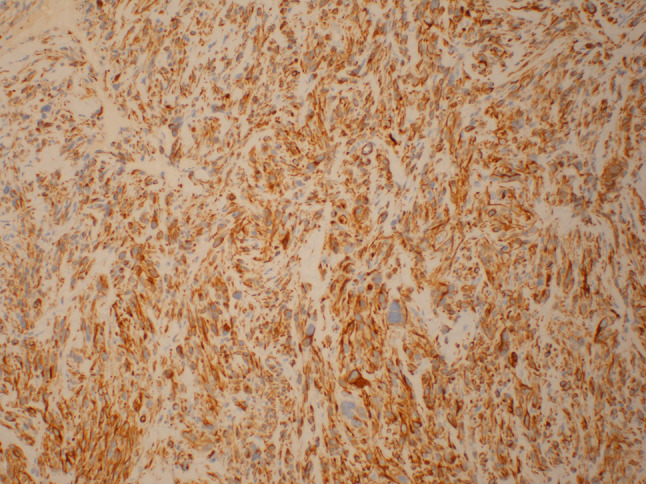

Fig. 3.

Desmin staining (×100) demonstrates diffuse strong staining in the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells

Fig. 4.

Muscle specific actin (×100) demonstrates diffuse moderate staining in the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells

Fig. 5.

Smooth muscle actin (×100) demonstrates diffuse strong staining in the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells

Review of the Literature

In the literature, there have been 16 cases of reported primary leiomyosarcoma of the buccal mucosa, including the present case, summarized in Table 1. A literature search revealed cases involving 6 males and 10 female patients who at presentation ranged in age between 6 and 88 years old (median age was 36.5 years old). Though designation of tumor in some reports included “cheek,” suggesting a dermal location, all tumors occurred in the oral cavity proper. Tumors ranged in dimension from 1.0 to 10.0 cm (median was 2.0 cm; tumor size was not available in our case, but the grade was moderately differentiated). There was one report of metastasis to regional lymph node. Initial treatment consisted of surgical excision alone in nine cases; a combination of surgery and radiation was reported in one case; a combination of surgery and chemotherapy with radiation was reported in one case; and treatment was refused in one case (treatment information was not available in four cases). Follow up information was available in 11 of the 16 cases, and ranged from 3 to 52 months (with a median of 22 months). Recurrence occurred in three cases. Overall, two patients died of their disease; one patient was alive with disease; and eight patients were alive with no evidence of tumor (follow up information was not available for five cases).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical data of primary buccal mucosal leiomyosarcoma

| Authors (year) | Age (years) | Gender | Primary site | Size (cm) | Metastasis | Initial treatment | Follow-up (months)—outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson and Whyte (1978) [20] | 88 | M | Cheek | 4.0 | n/r | Surgery (recur) | n/a—ANED |

| Schenberg et al. (1993) [3] | 42 | M | Buccal mucosa | 3.0 | n/r | Surgery | 32—ANED |

| Schenberg et al. (1993) [3] | 38 | M | Buccal mucosa | 2.0 | n/r | Surgery | 15—ANED |

| Mesquita et al. (1998) [21] | 23 | F | Buccal mucosa | 2.0 | n/r | Surgery | 24 - ANED |

| Montgomery et al. (2002) [14] | 38 | F | Cheek | 2.0 | n/r | n/a | n/a |

| Montgomery et al. (2002) [14] | 42 | M | Buccal | 5.0 | n/r | n/a | n/a |

| Yadav and Bharathan (2008) [22] | 27 | F | Buccal mucosa | 1.5 × 1.5 | n/r | Surgery | 18—ANED |

| Ethunandan et al. (2007) [23] | 51 | M | Buccal mucosa | 2.0 × 2.0 | n/r | Surgery | 28—ANED |

| Yan et al. (2009) [4] | 11 | F | Cheek | 4.0 × 4.0 | n/r | Surgery (recur) | 20—AWD |

| Yan et al. (2009) [4] | 21 | F | Cheek | 2.0 × 1.0 | n/r | Surgery and chemoradiation | 48—ANED |

| Yan et al. (2009) [4] | 16 | F | Cheek | 4.0 × 4.0 | n/r | Surgery | n/a |

| Yan et al. (2009) [4] | 12 | F | Cheek | 5.0 × 5.0 | n/r | Surgery and radiation (recur) | 8—DED |

| Yan et al. (2009) [4] | 6 | F | Cheek | 10.0 × 5.0 | Lymph node | Refused treatment | 3—DED |

| Nagpal et al. (2013) [24] | 35 | F | Buccal mucosa | 1.0 × 1.0 | n/r | n/a | n/a |

| Suarez-Alen et al. (2015) [25] | 66 | F | Buccal mucosa | 2.0 × 1.0 | n/r | Surgery | 52—ANED |

| Present case (2017) | 87 | M | Buccal mucosa | NR | n/a | n/a | n/a |

n/r none reported, n/a not available, AWD alive with disease, ANED alive with no evidence of disease, DED dead of disease

Discussion

The current case reports a primary leiomyosarcoma of the buccal mucosa. However, the vast majority of reported cases of leiomyosarcomas identified in the head and neck have involved the skin and soft tissues, with only a minority of cases involving the oral cavity (5.7%) and even fewer involving the skull and mandible (0.7%) [7]. Prior studies have also suggested that when leiomyosarcomas do involve the head and neck, there is greater likelihood for the jawbone to be involved with approximately 70% arising in the maxilla or mandible [3, 4, 8, 9].

Clinically, sarcomas of the head and neck present with non-specific signs and symptoms, and in the majority of cases these tumors manifest as a painless mass [3, 4, 10]. Distant metastases can occur in 28% of the patients at diagnosis or during follow-up and are more frequent in high grade sarcomas. The most frequently involved site for distant metastases is lung followed by bone, central nervous system, and liver [3, 10, 11]. In general, because of the low incidence of lymph node metastasis in sarcomas, formal lymph node dissection is often reserved for clinical involvement of regional lymph nodes [10]. However, leiomyosarcomas of the oral cavity, unlike leiomyosarcomas in soft tissue elsewhere, can metastasize to regional lymph nodes [6].

Histologic examination and immunohistochemical staining are essential for the final diagnosis of leiomyosarcomas [12, 13]. Leiomyosarcomas that occur in the oral cavity must be distinguished from other histologically similar, yet clinically benign lesion, such as infantile and adult myofibroma/myofibromatosis and angioleiomyomas [6]. The differential diagnosis of malignant spindle cell tumors in the head and neck includes spindle cell carcinoma and melanoma; sarcomas to be distinguished include malignant nerve sheath tumor and rhabdomyosarcoma [14]. Due to overlap in histologic features, head and neck sarcomas may be misdiagnosed or misclassified by the pathologist; one review of head and neck soft tissue sarcomas revealed a change in diagnosis by the pathologist in 33–48% of the cases [10]. Given these difficulties, Dry et al. pointed out that some of the previously reported cases that did not perform immunohistochemical studies, may in fact not be of myogenic origin [6]. Leiomyosarcomas are comprised of spindle cells with abundant fibrillary eosinophilic cytoplasm that mimic normal smooth muscle cells. They have oval nuclei that frequently have perinuclear vacuoles, similar to normal smooth muscle cells. The spindle cells of leiomyosarcomas are characteristically arranged in broad sweeping fascicles. Necrosis is common, as are mitotic figures, including atypical mitoses. As they often arise from the smooth muscle of vessel walls, origin from the outer surface of a vessel is commonly seen but not required for the diagnosis.

Cytogenetic studies of leiomyosarcomas have shown complex karyotypes with no consistent aberrations. Though a loss of chromosome 13 is frequent, suggesting involvement of the RB1 gene in a proportion of leiomyosarcomas [1], a decreased p16 expression has also been detected in 5–33% of leiomyosarcomas [2]. Even Epstein–Barr virus has been associated with leiomyosarcoma, albeit limited to those patients who were immunosuppressed [15]. Most recently, and previously unrecognized in leiomyosarcomas, chromothripsis (unique pattern of clustered rearrangement involving a single chromosome or few chromosomes [16]) and whole genome deletion were noted [17].

Aggressive surgical intervention remains the mainstay of management for patients with localized sarcomas of the head and neck [10, 18]. A retrospective analysis showed that administration of adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation for head and neck sarcomas did not have a significant impact on disease-free survival and disease-specific survival. Moreover, none of the patients who were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation without surgery achieved disease-free status [18]. Our own case review showed that surgical intervention with radiation and/or chemotherapy was by far the most frequent treatment option, unless the patient refused or the tumor location was deemed inoperable. The anatomy of the head and neck can limit the ability to obtain wide surgical margins, and thus may be a reason for higher local recurrence rate and a worse disease-specific survival compared to sarcomas arising at other, more accessible, sites [10, 11]. One group found that local recurrence rates for high-grade soft tissue sarcomas after surgical excision was 42%, most arising within 2 years of treatment [11]. For adult soft tissue sarcomas of all anatomic sites, tumor diameter larger than 5 cm, high histologic grade, and positive surgical margins are all correlated with an increased local recurrence rate, distant failure, and a reduced disease-specific survival [7, 10].

It has been suggested that the location of a leiomyosarcoma may be more important than its histologic features, prognostically speaking, as histopathologic examination appears to be limited for predicting the clinical behavior and prognosis of these smooth muscle tumors [3, 13]. At the same time, Eppsteiner et al., found that the 5-year disease-specific survival for well-differentiated leiomyosarcomas was 87.6% compared with 52.7% for poorly differentiated ones [7]. Furthermore, at most locations, mitoses and necrosis do appear to be the best histologic predictors of malignant behavior and presence of these feature should be evidence in favor of malignancy [19].

Conclusion

With only 16 reported cases of oral leiomyosarcoma in the buccal mucosa, it is difficult to draw broad conclusion about its clinical behavior, prognosis, and optimal treatment. Moreover, predicting clinical behavior of these rare but aggressive tumors has remained elusive. Nevertheless, there appears to be some semblance of guidance on appropriate management for disease-free survival, which begins with an astute clinician who suspects that a painless nodule in the cheek may require further investigation via a tissue biopsy; a thorough histologic examination and immunohistochemical work up for a definitive diagnosis; and, if circumstances permit, early surgical excision with tumor-free margins and prolonged follow up.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Authors Eugene M. Ko and Jonathan McHugh declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Solar AA, Jordan RC. Soft tissue tumors and common metastases of the oral cavity. Periodontol 2000. 2011;57(1):177–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schutz A, Smeets R, Driemel O, Hakim SG, Kosmehl H, Hanken H, Kolk A. Primary and secondary leiomyosarcoma of the oral and perioral region–clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of a rare entity with a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(6):1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schenberg ME, Slootweg PJ, Koole R. Leiomyosarcomas of the oral cavity. Report of four cases and review of the literature. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 1993;21(8):342–347. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(05)80495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan B, Li Y, Pan J, Xia H, Li LJ. Primary oral leiomyosarcoma: a retrospective clinical analysis of 20 cases. Oral Dis. 2010;16(2):198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo Muzio L, Favia G, Mignogna MD, Piattelli A, Maiorano E. Primary intraoral leiomyosarcoma of the tongue: an immunohistochemical study and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2000;36(6):519–524. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(00)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dry J, Fletcher M. Leiomyosarcomas of the oral cavity: an unusual topographic subset easily mistaken for nonmesenchymal tumours. Histopathology. 2000;36(3):210–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eppsteiner RW, DeYoung BR, Milhem MM, Pagedar NA. Leiomyosarcoma of the head and neck: a population-based analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(9):921–924. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izumi K, Maeda T, Cheng J, Saku T. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the maxilla with regional lymph node metastasis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80(3):310–319. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(05)80389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilos GA, Rapidis AD, Lagogiannis GD, Apostolidis C. Leiomyosarcomas of the oral tissues: clinicopathologic analysis of 50 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(10):1461–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bree R, Van Der Waal I, De Bree E, René Leemans C. Management of adult soft tissue sarcomas of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(11):786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh RP, Grimer RJ, Bhujel N, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Abudu A. Adult head and neck soft tissue sarcomas: treatment and outcome. Sarcoma. 2008 doi: 10.1155/2008/654987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn JH, Mirza T, Ameerally P. Leiomyosarcoma of the tongue with multiple metastases: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(7):1745–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.06.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikitakis NG, Lopes MA, Bailey JS, Blanchaert RH, Jr, Ord RA, Sauk JJ. Oral leiomyosarcoma: review of the literature and report of two cases with assessment of the prognostic and diagnostic significance of immunohistochemical and molecular markers. Oral Oncol. 2002;38(2):201–208. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery E, Goldblum JR, Fisher C. Leiomyosarcoma of the head and neck: a clinicopathological study. Histopathology. 2002;40(6):518–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Flores A. Epstein-Barr virus in cutaneous pathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35(8):763–786. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318287e0c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang CZ, Spektor A, Cornils H, Francis JM, Jackson EK, Liu S, Meyerson M, Pellman D. Chromothripsis from DNA damage in micronuclei. Nature. 2015;522(7555):179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature14493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chudasama P, Mughal SS, Sanders MA, Hubschmann D, Chung I, Deeg KI, Wong SH, Rabe S, Hlevnjak M, Zapatka M, et al. Integrative genomic and transcriptomic analysis of leiomyosarcoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):144. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02602-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang AE, Chai X, Pollack SM, Loggers E, Rodler E, Dillon J, Parvathaneni U, Moe KS, Futran N, Jones RL. Analysis of clinical prognostic factors for adult patients with head and neck sarcomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(6):976–983. doi: 10.1177/0194599814551539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnan V, Miyaji CM, Mainous EG. Leiomyosarcoma of the mandible: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49(6):652–655. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90350-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson EC, Whyte AM. Leiomyosarcoma of the cheek: a case report. Br J Oral Surg. 1978;16(2):100–104. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(78)90018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesquita RA, Migliari DA, de Sousa SO, Alves MR. Leiomyosarcoma of the buccal mucosa: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56(4):504–507. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(98)90723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yadav R, Bharathan S. Leiomyosarcoma of the buccal mucosa: a case report with immunohistochemistry findings. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(2):215–218. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ethunandan M, Stokes C, Higgins B, Spedding A, Way C, Brennan P. Primary oral leiomyosarcoma: a clinico-pathologic study and analysis of prognostic factors. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36(5):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagpal DKJ, Prabhu PR, Shah A, Palaskar S. Leimyosarcoma of the buccal mucosa and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17(1):149. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.110732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suarez-Alen F, Otero-Rey E, Penamaria-Mallon M, Garcia-Garcia A, Blanco-Carrion A. Oral leiomyosarcoma: the importance of early diagnosis. Gerodontology. 2015;32(4):314–317. doi: 10.1111/ger.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]