Abstract

Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia (LJSGH) is a gingival lesion with unique clinicopathologic features that may involve synchronously multiple sites. We present a case with lesions clinically consistent with LJSGH in four jaw quadrants, confirmed by biopsy and review the English literature on multifocal LJSGH cases. A 19 year-old woman presented with circumscribed, erythematous overgrowths on the right and left maxillary and mandibular gingiva. With the provisional diagnosis of multifocal LJSGH, total excision of four maxillary lesions was performed. Clinical, microscopic and immunohistochemical examination with cytokeratin 19 confirmed the diagnosis of LJSGH in multiple sites. The excised lesions showed partial to complete recurrence after 4 months, while spontaneous regression of all but one lesion was observed after 15 months. Twenty cases with synchronous involvement of the gingiva of at least two teeth were previously reported. Their clinical features were comparable to that of solitary LJSGH. Only one case involved all four jaw quadrants. Spontaneous remission has not been documented before. The recognition of multiple lesions with clinicopathologic features diagnostic of LJSGH in the same adult patient argue against the designations “localized” and “juvenile”. Recurrences are common, while remission might occur.

Keywords: Spongiotic gingival hyperplasia, Multifocal, Generalized, Localized, Gingivitis

Introduction

Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia (LJSGH) is a lesion with unique clinicopathologic features and unclear pathogenesis [1] that was initially described as juvenile spongiotic gingivitis [2]. It is considered as a rare lesion and represented only 0.069% of 31,469 biopsies accessioned in an oral pathology laboratory during a 7-year period [3].

As the name of the lesion implies, it usually affects patients younger than 18 years, in particular in the first 5 years or the second decade of life [1–3]. However, as the age of reported cases ranges from 5 to 39 years [1, 2], the designation juvenile is not always justified. There is a preference for Caucasians [1] and no clear gender predominance [1–3]. Clinically, it presents as a solitary gingival mass with a bright red color and papillary or granular surface, measuring 0.2 to 1 cm in maximum dimension, usually located on the labial maxillary gingiva. The mass is painless, but has a propensity for bleeding [1]. Although LJSGH is by definition a localized lesion, patients presenting with more than one lesion clinically consistent with LJSGH have been described [1–7]. Microscopic examination reveals the presence of non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium showing papillomatosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, interconnecting rete pegs, interstitial edema and inflammatory cell exocytosis, mainly by neutrophils. The underlying connective tissue is edematous and vascularized with diffuse inflammatory infiltration by lymphocytes, neutrophils and plasma cells [1, 2, 4, 8].

We present the case of a young adult female with lesions clinically consistent with LJSGH in all four quadrants of her mouth, with confirmation of the diagnosis by biopsy. The excised lesions showed partial to complete recurrence 4 months later, while spontaneous regression of all but one lesion was noticed 15 months after biopsy. The English literature on multifocal cases of LJSGH is also reviewed.

Case Presentation

A 19 year-old woman presented for diagnosis and management of “bright red elevated gums”. According to the patient gingival erythema was first noticed “many years ago”, but recently gingival bleeding on brushing was seen and gingival overgrowths developed. Dental plaque removal and root scaling by her dentist, followed by topical application of chlorhexidine gel 0.5% and per os amoxicillin 500 mg three times daily for 1 week stopped bleeding, but the gingival overgrowths remained unchanged. Her medical history included amenorrhea with elevated 17-OH progesterone due to polycystic ovarian syndrome, treated with norethisterone. She did not smoke and her recent total blood count was within normal limits.

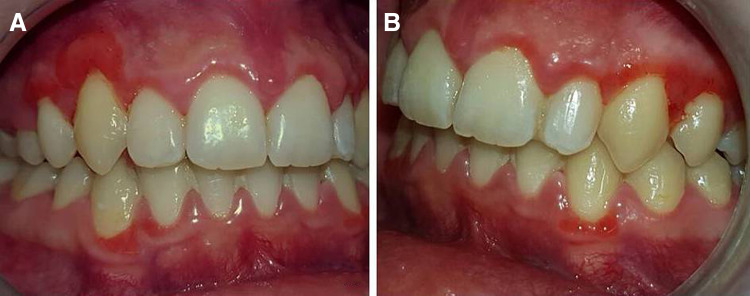

Intraoral examination revealed three well-circumscribed, bright red, pedunculated overgrowths with papillary surface, measuring 0.7 cm in greatest dimension, on the facial marginal and attached gingiva of the maxillary right canine (Fig. 1a) and the maxillary left canine and first premolar (Fig. 1b). Red bands with papillary surface were observed along the labial marginal gingiva of maxillary right lateral incisor and first premolar (Fig. 1a), mandibular right lateral incisor and canine, and mandibular left canine (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Clinical examination. Well-circumscribed, bright red, pedunculated overgrowths with papillary surface, on the labial marginal and attached gingiva of a maxillary right lateral incisor to first premolar, b maxillary left canine and first premolar, and c mandibular right lateral incisor and canine, and left canine

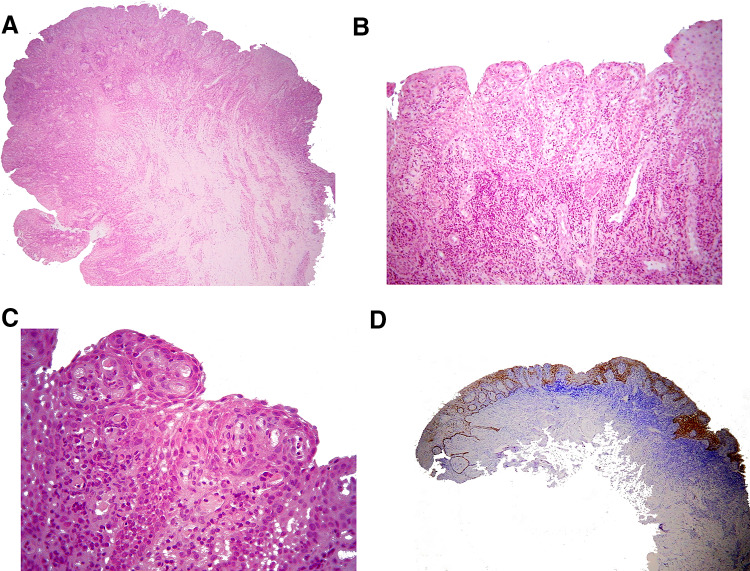

With the provisional diagnosis of LJSGH in multiple sites total excision of the lesions was suggested. However, due to the reluctance of the patient to have all lesions removed, only the lesions at the gingiva of the maxillary canines and premolars were excised under local infiltration anesthesia for esthetic purposes. The tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and 5 µm thick paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Microscopic examination revealed mucosal fragments covered by non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 2a), showing papillary surface, acanthosis, spongiosis, focally elongated and interconnecting rete pegs, as well as neutrophilic exocytosis (Fig. 2b). The underlying connective tissue was vascular with dense inflammatory infiltrations mostly by neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 2c). Immunohistochemistry with a standard streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase method using the monoclonal mouse anti-human cytokeratin (CK) 19 (1:100, Clone RCK108, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) showed intense cytoplasmic positivity of the lesional epithelium in all cell layers, whereas the adjacent gingival epithelium was CK19 positive only in the basal cell layer (Fig. 2d). The clinical, microscopic and immunohistochemical findings were consistent with LJSGH in multiple sites.

Fig. 2.

a Microscopic examination revealed mucosal fragments covered by non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, with papillary surface (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×25). b Microscopically, the lesion was covered by non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, showing papillary surface, acanthosis, spongiosis, focally elongated and interconnecting rete pegs, as well as neutrophilic exocytosis (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100). c The lesional epithelium was characterized by acanthosis, spongiosis, focally elongated and interconnecting rete pegs and neutrophilic exocytosis. The underlying connective tissue was vascular with dense inflammatory infiltrations mostly by neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×400). d Intense cytoplasmic positivity of CK19 in all cell layers of lesional epithelium, but only in the basal cell layer of the adjacent gingival epithelium (streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase, original magnification ×25)

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was advised to use a topical chlorhexidine gel 0.5% until healing of the biopsy traumas and to follow a proper oral hygiene program, including teeth brushing and flossing twice daily. On re-examination 4 months later, the excised lesions had recurred, fully around the right upper canine and first premolar (Fig. 3a) and partly around the left (Fig. 3b). The lesions on the mandibular facial, marginal gingiva were unchanged.

Fig. 3.

Re-examination 4 months post biopsy. Recurrence of excised lesions, totally around the right upper canine and first premolar (a) and partly around the left (b). No change is noticed on lesions of the mandibular facial, marginal gingiva

Eleven months later, the lesion around the maxillary right canine remained unchanged (Fig. 4a); around the mandibular right lateral incisor, right canine and left canine had significantly regressed; and around the maxillary right first premolar, left canine and left first premolar had completely resolved (Fig. 4a–c). A re-examination after 6 months is scheduled.

Fig. 4.

Re-examination 15 months post biopsy. The lesion (a) around the maxillary right canine is unchanged; (b) around the mandibular right lateral incisor, right canine and left canine has significantly regressed; and (a–c) around the maxillary right first premolar, left canine and left first premolar has disappeared

Discussion

The present case is unusual due to the presence of lesions with clinical features consistent with LJSGH in all four quadrants of jaws, confirmed by biopsy in two of them, as well as for evidence of regression over time.

Our review of the English literature on cases of LJSGH with synchronous involvement of the gingiva of at least two teeth found 20 cases with microscopic documentation [1–7], representing 16.3% of 123 reported LJSGH cases [1–14]. This number may be an underestimation, as some cases of LJSGH may have been diagnosed as adolescent gingivitis [2]. Table 1 summarizes the main clinical features of those 20 cases [1–14] and the present one. Two cases (case 4 in [10, 15]) were excluded, as there was no histopathologic confirmation. Clinical features were available in 19/21 patients and are comparable to that of LJSGH with solitary lesions [1–3]. There is no clear gender preponderance (male to female ratio 1:0.9); age at diagnosis ranges between 5 and 28 years (mean age 13.1 ± 5.15 years), but most patients are in the second decade of life; two patients had primary dentition [2] and four were adults [2, 4]. Our patient was also an adult, but she reported that the lesions were first noticed many years ago, apparently when she was a teenager.

Table 1.

Literature review of microscopically documented cases of spongiotic gingival hyperplasia synchronously involving multiple sites

| References | Sex | Age | Maxillary gingiva | Mandibular gingiva | NA site | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP | RA | LA | LP | RP | RA | LA | LP | ||||

| Darling et al. 2007 [2] | M | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| M | 6 | ✓ | |||||||||

| F | 12 | ✓ | |||||||||

| F | 11 | ✓ | |||||||||

| F | 11 | ✓ | |||||||||

| F | 11 | ✓ | |||||||||

| M | 13 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| F | 28 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| M | 18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| M | 12 | ✓ | |||||||||

| M | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| F | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Chang et al. 2008 [1] | NA | NA | ✓a | ||||||||

| MacNeil et al. 2011 [5] | M | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Solomon et al. 2013 [7] | M | 15 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| M | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Argyris et al. 2015 [3] | NA | NA | ✓ | ||||||||

| de Freitas et al. 2015 [4] | M | 18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Nogueira et al. 2016 [6] | F | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| F | 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Present case | F | 19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

RP right posterior, RA right anterior, LA left anterior, LP left posterior, NA not available, M male, F female

aNot available exact site of lesions involving both maxillary and mandibular gingiva

Nine and 2 of 17 cases in which locations were known involved the maxillary and mandibular gingiva exclusively (Table 1). Six cases affected one jaw quadrant [2] and 5 cases two quadrants [2, 5]. Gingival lesions in three quadrants were described in four cases [2, 6, 7], while involvement of all four quadrants, as in the case presented herein, has been previously reported only once [4]. In one case with multifocal lesions, involvement of the second quadrant occurred a few months later [5]. In 16 of 17 cases the anterior facial gingiva were affected, usually the marginal gingiva [4, 6], occasionally simultaneously with the attached gingiva [2, 5, 7] and the interdental papillae [5, 7].

The differential diagnosis of LJSGH with synchronous involvement of multiple sites has been thoroughly discussed by de Freitas et al. [4] and the most common clinical diagnosis in these cases is dental plaque-induced puberty gingivitis [1–4].

Dental plaque and calculus accumulation, foreign body integration, trauma, orthodontic appliances, oral breathing, viruses, sex hormones and developmental abnormalities have been implicated in the pathogenesis of LJSGH, but a causal relationship with any of them has not been established [1–3, 7]. In the present case, the patient had a history of ovarian syndrome managed with norethisterone. An association of LJSGH with that hormonal status has not been previously described, but as LJSGH may appear in prepubertal patients of both genders [1, 2], and estrogen and progesterone receptors were not detected in LJSGH [2], the involvement of sex hormones seems unlikely. The prevailing theory concerning the pathogenesis of LJSGH is focused on its microscopic and immunohistochemical similarities with junctional epithelium of gingiva, in particular its positivity for CK19 [2, 8]. This theory suggests that LJSGH results from “exteriorization” of junctional epithelium that under the influence of local environmental stimuli might gradually acquire oral gingival epithelium-associated features in order to adjust to its new environment [8]. The present case seems to be the first one where CK19 expression was documented in LJSGH with involvement of multiple sites.

Excision of the lesions with scalpel [1–3, 7, 12] or laser [3, 5] is the gold standard of solitary lesions [6, 7], and cryotherapy was described recently as an efficient alternative treatment for multiple lesions [6]. Topical steroid therapy was ineffective in one case [4], whereas in another case resulted in transient clinical improvement of the lesion {figure 5 in [10]}. Scaling and removal of dental plaque do not improve the clinical presentation [1–3, 5].

Recurrence occurred in 5 [2, 6, 7] of 13 [2, 4–7] cases with available information, 1 [6] to 6 [7] months after excision. The 38.5% recurrence rate of multifocal cases is greater than the corresponding percentage of solitary LJSGH that was 5.8–28.6% [1–3]. No factors related to high risk of recurrence have been identified [7]. Two of the excised lesions in our patient recurred within the first 4 months.

Anecdotal evidence of spontaneous remission has been mentioned previously [2], without further documentation [6]. In our case, remission of three previously biopsized maxillary lesions that initially showed features of re-growth, as well as resolution of the mandibular lesions was seen in the 15-month follow-up period. Spontaneous remission of LJSGH might be attributed to the elimination of a possible, yet unknown, causative factor.

In conclusion, the recognition of multiple lesions with clinicopathologic features diagnostic of LJSGH in the same patient, as well as the wide age variation of the patients, argue in favor of an alternative name for such lesions, i.e. spongiotic gingival hyperplasia as proposed Solomon et al. [7]. As the lesion may spread [5] and often recur [1–3, 6, 7], the patients should be regularly re-examined.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All Authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Chang JY, Kessler HP, Wright JM. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(3):411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darling MR, Daley TD, Wilson A, Wysocki GP. Juvenile spongiotic gingivitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7):1235–1240. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argyris PP, Nelson AC, Papanakou S, Merkourea S, Tosios KI, Koutlas IG. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia featuring unusual p16INK4A labeling and negative human papillomavirus status by polymerase chain reaction. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44(1):37–44. doi: 10.1111/jop.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Freitas Silva BS, Silva Sant’Ana SS, Watanabe S, Vencio EF, Roriz VM, Yamamoto-Silva FP. Multifocal red bands of the marginal gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2015;119(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacNeill SR, Rokos JW, Umaki MR, Satheesh KM, Cobb CM. Conservative treatment of localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2011;1(3):199–204. doi: 10.1902/cap.2011.110003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nogueira VK, Fernandes D, Navarro CM, Giro EM, de Almeida LY, Leon JE, et al. Cryotherapy for localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia: preliminary findings on two cases. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017;27(3):231–235. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon LW, Trahan WR, Snow JE. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia: a report of 3 cases. Paediatr Dent. 2013;35(4):360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allon I, Lammert KM, Iwase R, Spears R, Wright JM, Naidu A. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia possibly originates from the junctional gingival epithelium-an immunohistochemical study. Histopathology. 2016;68(4):549–555. doi: 10.1111/his.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damm DD. Gingival red patch. Juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. Gen Dent. 2009;57(4):448–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes DT, Wright JM, Lopes SMP, Santos-Silva AR, Vargas PA, Lopes MA. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia: a report of 4 cases and literature review. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2017 doi: 10.1902/cap.2017.170018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flaitz CM, Longoria JM. Oral and maxillofacial pathology case of the month. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. Texas Dent J. 2010;127(12):1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalogirou EM, Chatzidimitriou K, Tosios KI, Piperi EP, Sklavounou A. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia: report of two cases. J Clini Pediatr Dent. 2017;41(3):228–231. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-41.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noonan V, Lerman MA, Woo SB, Kabani S. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia. J Massachusetts Dent Soc. 2013;62(2):45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossmann JA. Reactive lesions of the gingiva: diagnosis and treatment options. Open Pathol J. 2011;5:23–32. doi: 10.2174/1874375701105010023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decani S, Baruzzi E, Sutera S, Trapani A, Sardella A. A case of juvenile spongiotic gingivitis. Annali di stomatologia. 2013;4(Suppl 2):41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]