Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a very prevalent breathing disorder (Peppard et al., 2013; Heinzer et al., 2015) characterized by recurrent obstructions of the upper airway during sleep. These obstructions, which can present as either frank apneas or hypopneas, result in cyclic events of arterial hypoxemia with or without hypercapnia since blood circulating through lung capillaries during the obstructive events does not receive the required amount of oxygen because interrupted ventilation reduces the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) in alveolar air. Intermittent arterial hypoxemia immediately translates into the systemic capillary circulation with the result that all patient's tissues are subjected to cycles of hypoxia/reoxygenation of varying severity (Almendros et al., 2010, 2011, 2013; Reinke et al., 2011; Torres et al., 2014; Moreno-Indias et al., 2015). There is now ample experimental and epidemiological evidence that the oxidative stress and inflammatory cascades elicited at both systemic and tissue levels by the recurrent hypoxia-reoxygenation events are major drivers of the clinically relevant morbid consequences of OSA (Lavie, 2015), namely increased risk of cardiovascular, metabolic, neurocognitive and malignant diseases (Lévy et al., 2015). Given the major health care burden posed by OSA and the ethical impossibility of carrying out precise mechanistic studies focused on causality in patients with OSA, considerable efforts have been preferentially focused on animal models of OSA (Davis and O'Donnell, 2013; Chopra et al., 2016) and more particularly on those mimicking intermittent hypoxemia.

To realistically model intermittent hypoxemia in OSA it is important to bear in mind that the potential effect of this exposure depends on the magnitude of the decrease in arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2), since this biological variable de facto determines the PO2 gradient across the capillary membrane, and hence oxygen delivery to cells within the various tissues. In practice, the conventional setting for subjecting animals to intermittent hypoxia consists of cyclically changing the oxygen fraction (FiO2) in the environmental gas breathed by the animals from room air (FIO2 - 21%) to different nadir values ranging from FIO2 of 4 to 15%, and thus model different degrees of hypoxia severity which, as would be anticipated, yield dose-response effects (Nagai et al., 2014; Lim et al., 2016; Gallego-Martin et al., 2017; Docio et al., 2018). When using this experimental setting the degree of intermittent hypoxemia achieved for a given FiO2 swing is similar in young and old animals (Dalmases et al., 2014) which is interesting given that the effects of hypoxia/reoxygenation are modulated by age (Torres et al., 2018). The conventional settings used for applying intermittent hypoxia to animals include two major parameters, with one of them being the frequency of hypoxic events [which loosely corresponds to the clinical index of apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) recorded in polysomnographic studies of patients with OSA, Berry et al., 2018]. Setting the frequency of intermittent hypoxia to mimic different values of AHI is a relatively straightforward proposition, and different investigators have carried out animal experiments in which they modeled varying rates of hypoxic events such as to cover a wide range of AHI, e.g., from the highest events rates in OSA patients (60 events/h) to occasional events (2 events/h) (Almendros et al., 2013; Shiota et al., 2013; Dalmases et al., 2014; Jun et al., 2014; Briançon-Marjollet et al., 2016; Gozal et al., 2017). Moreover, at any given frequency of cycling it is also simple to prescribe different durations for the de-oxygenation and re-oxygenation phases within each cycle (Chodzynski et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2015).

The second major index defining the characteristics of the experimental OSA paradigm is the severity of the hypoxic stimulus within each event. Determining the severity of the actual intermittent hypoxemia in OSA patients by measuring the variable which is physiologically relevant in terms of oxygen transport to tissues in systemic capillaries (PaO2) is not easy, particularly when taking into account that in OSA this variable changes at a high frequency. Such real time measurements would only be possible if using fast fiberoptic oxygen sensors suitable for human use and capable of continually measure fast variations of oxygen partial pressure in blood (Formenti et al., 2015) or by a technique of repetitive blood sampling along the obstructive events as carried out in animals (Lee et al., 2009). However, such invasive or complex measurements are clearly not appropriate for OSA patients in clinical settings, especially when considering that indirect estimates of PaO2 can be easily and non-invasively obtained by means of pulse oximetry. Indeed, this technique –which provides real time measurement of SaO2 (i.e., the percentage of oxy-hemoglobin in arterial blood within each heartbeat) – is an accurate surrogate of PaO2 since for conventional conditions (e.g., pH, temperature) the oxygen dissociation curve of human blood provides a direct relationship between PaO2 and SaO2 (Severinghaus, 1979). Given the ease of its measurement, pulse oximetry is currently the standard tool to clinically quantify the severity and duration of hypoxic events in OSA patients (Berry et al., 2018). Fortunately, pulse oximetry can be also applied to measure SaO2 in animals. Indeed, given that hemoglobin from different species presents virtually the same absorption properties in the visible and near infrared regions (Grosenbaugh et al., 1997), pulse oximeters for small animals only require software adaptations to deal with much higher heart rate frequencies than in humans, even if they make inferential assumptions and annul considerations regarding potential differences across saturation equations in rodents. Nevertheless, characterizing the depth of the hypoxemic events in animal models of OSA and compare them with those in patients is not straightforward, and constitutes a controversial issue in sleep apnea research. Furthermore, the potential presence of hemodynamic instability, tissue perfusion changes, and accuracy issues of oximeters at the low ranges of saturation need to be considered as well. This Opinion article aims to contribute to this topic discussion by illustrating important considerations and evidence in this contextual setting.

The major controversial point refers to one of the most commonly employed paradigms of intermittent hypoxia when applied to mice, and resulting in measured SaO2 swings with nadir values in the range 50–70% (Jun et al., 2010; Reinke et al., 2011; Torres et al., 2014, 2015; Lim et al., 2015, 2016). Specifically, in a recent review focused on sleep apnea research in animals, it was stated that such intermittent hypoxia profiles may result in significantly more severe hypoxic events than those typically experienced by patients with OSA, in whom SaO2 nadir ranges of 77–90% are usually documented (Lim et al., 2015), and that therefore extrapolation from murine models to human disease should be applied with caution (Chopra et al., 2016). As will become apparent from the following discussion, we disagree with such an objection, and instead state that such low SaO2 nadirs (50–70%) in mice realistically mimic the hypoxemic events in patients since they actually correspond to PaO2 values similar to those in OSA patients. The rationale behind such assertion is that SaO2 is misleading when comparing severity of hypoxemia across different species because the oxygen dissociation curve in mice is considerably different from humans, and this point will be reinforced while we elaborate on well-established physiological data depicting oxygen dissociation curves across species.

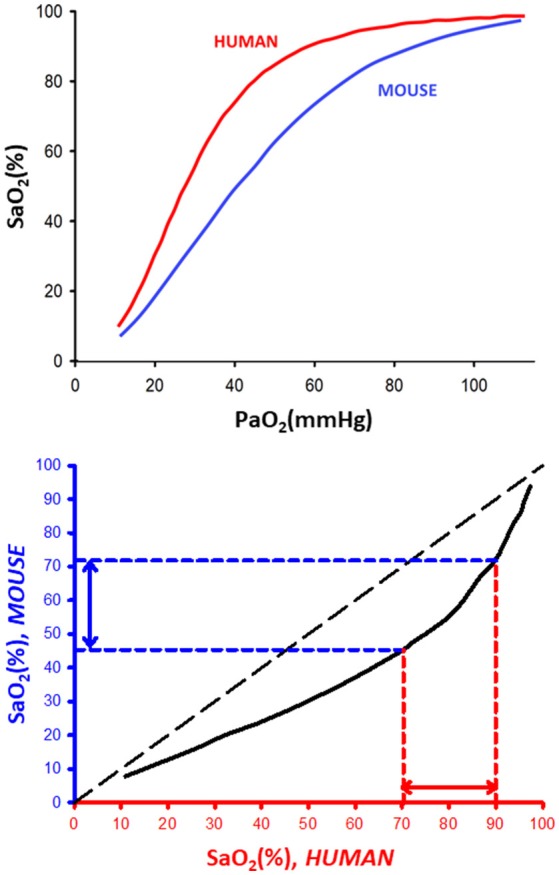

The top of Figure 1 shows a representation of the typical SaO2-PaO2 relationships in human (red line) and mouse (blue line). The usually overlooked fundamental fact that there is a shift of the oxygen dissociation curve toward the right as the body size of the species decreases was already firmly established 60 years ago (Schmidt-Neilsen and Larimer, 1958). More specifically, half-saturation pressure (P50), defined as PaO2 corresponding to SaO2 = 50%, and typical body weight (BW) of any mammalian species were shown to be closely prescribed by a classical heterogonic relationship (Adolph, 1949) in biological scaling (Schmidt-Nielsen, 1970): P50 = 50.34 × BW−0.054 (P50 in mmHg, BW in grams), for a range of mammals encompassing horse to mouse (Schmidt-Neilsen and Larimer, 1958). It is also remarkable that the Bohr effect (shifting of the dissociation curve as blood CO2/pH increases/decreases) applies to mammalian blood with a magnitude range that also closely follows a heterogonic relationship (Riggs, 1960), a factor that could further amplify the human-mouse difference, particularly when CO2 increases during obstructive apneas are taken into account (Farré et al., 2007). Interestingly, the earlier reports on detectable differences among hemoglobin dissociation curves in human and mouse blood have been subsequently confirmed as measurement techniques have improved (Gray and Steadman, 1964; Severinghaus, 1979; Mouneimne et al., 1990; Geng et al., 2016). Figure 1 (top) clearly shows that for any given SaO2 value, PaO2 is always lower for human than for mouse blood. In other words, mice have more oxygen reserve than humans. These data can be plotted as the relationship between SaO2 in mice and humans for any value of PaO2 as shown in the bottom panel of Figure 1, illustrating that SaO2 in mice is always below the identity line. This figure shows that the typical range of SaO2 nadir values in patients (70–90%) corresponds to nadir SaO2 values in the range 45–72% in mice, thereby firmly confirming the adequacy of current experimental environmental hypoxia protocols used in murine models.

Figure 1.

(Top) Representative oxygen dissociation curves for human and mouse blood. SaO2 and PaO2: arterial oxygen saturation and partial pressure, respectively. The dissociation curves for human and mouse blood were redrawn from data in Severinghaus (1979) and Geng et al. (2016), respectively. (Bottom) Relationship between equivalent (same PaO2) values of SaO2 in human and mouse blood.

In conclusion, to achieve PaO2 nadir values similar to those traditionally experienced by severe OSA patients –i.e., to realistically simulate patients' hypoxia– SaO2 in mice should be much lower than the SaO2 observed in patients. These considerations substantiate our initial objection to the statement by Chopra and coauthors (Chopra et al., 2016) that the currently used experimental paradigms of intermittent hypoxia (SaO2 swings with nadir 50–70%) in mice are not at all excessively severe, but rather closely match human conditions. Therefore, current intermittent hypoxia exposure paradigms adequately and reliably perform when subjecting mouse cells in the various tissues to a realistic hypoxia/reoxygenation challenge that enables investigation of mechanisms underlying the end-organ adverse consequences of OSA.

Author contributions

RF conceived and drafted the manuscript. JM, DG, IA, and DN provided their expertise in animal models, respiratory physiology and pathophysiology of sleep apnea, and significantly contributed to write the final version.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (SAF2017-85574-R, DPI2017-83721-P; AEI/FEDER, UE) and Generalitat de Catalunya (CERCA Program).

References

- Adolph E. F. (1949). Quantitative relations in the physiological constitutions of mammals. Science 109, 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almendros I., Farré R., Planas A. M., Torres M., Bonsignore M. R., Navajas D., et al. (2011). Tissue oxygenation in brain, muscle, and fat in a rat model of sleep apnea: differential effect of obstructive apneas and intermittent hypoxia. Sleep 34, 1127–1133. 10.5665/SLEEP.1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almendros I., Montserrat J. M., Torres M., Dalmases M., Cabañas M. L., Campos-Rodríguez F., et al. (2013). Intermittent hypoxia increases melanoma metastasis to the lung in a mouse model of sleep apnea. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 186, 303–307. 10.1016/j.resp.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almendros I., Montserrat J. M., Torres M., González C., Navajas D., Farré R. (2010). Changes in oxygen partial pressure of brain tissue in an animal model of obstructive apnea. Respir. Res. 11:3. 10.1186/1465-9921-11-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry R. B., Altertario C. L., Harding S. M., Llyod R. M., Plante D. T., Quan S. F., et al. (2018). The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.5. Darin, IL: America Academy of Sleep Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Briançon-Marjollet A., Monneret D., Henri M., Hazane-Puch F., Pepin J. L., Faure P., et al. (2016). Endothelin regulates intermittent hypoxia-induced lipolytic remodelling of adipose tissue and phosphorylation of hormone-sensitive lipase. J. Physiol. 594, 1727–1740. 10.1113/JP271321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodzynski K. J., Conotte S., Vanhamme L., Van Antwerpen P., Kerkhofs M., Legros J. L., et al. (2013). A new device to mimic intermittent hypoxia in mice. PLoS ONE 8:e59973. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra S., Polotsky V. Y., Jun J. C. (2016). Sleep apnea research in animals. Past, present, and future. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 54, 299–305. 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0218TR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmases M., Torres M., Márquez-Kisinousky L., Almendros I., Planas A. M., Embid C., et al. (2014). Brain tissue hypoxia and oxidative stress induced by obstructive apneas is different in young and aged rats. Sleep 37, 1249–1256. 10.5665/sleep.3848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E. M., O'Donnell C. P. (2013). Rodent models of sleep apnea. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 188, 355–361. 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docio I., Olea E., Prieto-LLoret J., Gallego-Martin T., Obeso A., Gomez-Niño A., et al. (2018). Guinea pig as a model to study the carotid body mediated chronic intermittent hypoxia effects. Front. Physiol. 9:694. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré R., Nácher M., Serrano-Mollar A., Gáldiz J. B., Alvarez F. J., Navajas D., et al. (2007). Rat model of chronic recurrent airway obstructions to study the sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 30, 930–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formenti F., Chen R., McPeak H., Murison P. J., Matejovic M., Hahn C. E., et al. (2015). Intra-breath arterial oxygen oscillations detected by a fast oxygen sensor in an animal model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Br. J. Anaesth. 114, 683–688. 10.1093/bja/aeu407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Martin T., Farré R., Almendros I., Gonzalez-Obeso E., Obeso A. (2017). Chronic intermittent hypoxia mimicking sleep apnoea increases spontaneous tumorigenesis in mice. Eur. Respir. J. 49:1602111. 10.1183/13993003.02111-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X., Dufu K., Hutchaleelaha A., Xu Q., Li Z., Li C. M., et al. (2016). Increased hemoglobin-oxygen affinity ameliorates bleomycin-induced hypoxemia and pulmonary fibrosis. Physiol. Rep. 4:e12965. 10.14814/phy2.12965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D., Khalyfa A., Qiao Z., Almendros I., Farré R. (2017). Temporal trajectories of novel object recognition performance in mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia. Eur. Respir. J. 50:1701456. 10.1183/13993003.01456-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray L. H., Steadman J. M. (1964). Determination of the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curves for mouse and rat blood. J. Physiol. 175, 161–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosenbaugh D. A., Alben J. O., Muir W. W. (1997). Absorbance spectra of inter-species hemoglobins in the visible and near infrared regions. J. Vet. Emerg. 7, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzer R., Vat S., Marques-Vidal P., Marti-Soler H., Andries D., Tobback N., et al. (2015). Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: the HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir. Med. 3, 310–318. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00043-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J., Reinke C., Bedja D., Berkowitz D., Bevans-Fonti S., Li J., et al. (2010). Effect of intermittent hypoxia on atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 209, 381–386. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J. C., Shin M. K., Devera R., Yao Q., Mesarwi O., Bevans-Fonti S., et al. (2014). Intermittent hypoxia-induced glucose intolerance is abolished by α-adrenergic blockade or adrenal medullectomy. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 307, E1073–E1083. 10.1152/ajpendo.00373.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie L. (2015). Oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea and intermittent hypoxia–revisited–the bad ugly and good: implications to the heart and brain. Sleep Med. Rev. 20, 27–45. 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. J., Woodske M. E., Zou B., O'Donnell C. P. (2009). Dynamic arterial blood gas analysis in conscious, unrestrained C57BL/6J mice during exposure to intermittent hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 107, 290–294. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91255.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévy P., Kohler M., McNicholas W. T., Barbé F., McEvoy R. D., Somers V. K., et al. (2015). Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1:15015. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D. C., Brady D. C., Po P., Chuang L. P., Marcondes L., Kim E. Y., et al. (2015). Simulating obstructive sleep apnea patients' oxygenation characteristics into a mouse model of cyclical intermittent hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 118, 544–557. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00629.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D. C., Brady D. C., Soans R., Kim E. Y., Valverde L., Keenan B. T., et al. (2016). Different cyclical intermittent hypoxia severities have different effects on hippocampal microvasculature. J. Appl. Physiol. 121, 78–88. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01040.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Indias I., Torres M., Montserrat J. M., Sanchez-Alcoholado L., Cardona F., Tinahones F. J., et al. (2015). Intermittent hypoxia alters gut microbiota diversity in a mouse model of sleep apnoea. Eur. Respir. J. 45, 1055–1065. 10.1183/09031936.00184314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouneimne Y., Barhoumi R., Myers T., Slogoff S., Nicolau C. (1990). Stable rightward shifts of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve induced by encapsulation of inositol hexaphosphate in red blood cells using electroporation. FEBS Lett. 275, 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai H., Tsuchimochi H., Yoshida K., Shirai M., Kuwahira I. (2014). A novel system including an N2 gas generator and an air compressor for inducing intermittent or chronic hypoxia. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Physiol. 1, 307–310. 10.4103/2348-8093.149770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard P. E., Young T., Barnet J. H., Palta M., Hagen E. W., Hla K. M. (2013). Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 177, 1006–1014. 10.1093/aje/kws342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke C., Bevans-Fonti S., Drager L. F., Shin M. K., Polotsky V. Y. (2011). Effects of different acute hypoxic regimens on tissue oxygen profiles and metabolic outcomes. J. Appl. Physiol. 111, 881–890. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00492.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs A. (1960). The nature and significance of the Bohr effect in mammalian hemoglobins. J. Gen. Physiol. 43, 737–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Neilsen K., Larimer J. L. (1958). Oxygen dissociation curves of mammalian blood in relation to body size. Am. J. Physiol. 195, 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Nielsen K. (1970). Energy metabolism, body size, and problems of scaling. Fed. Proc. 29, 1524–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinghaus J. W. (1979). Simple, accurate equations for human blood O2 dissociation computations. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir. Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 46, 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota S., Takekawa H., Matsumoto S. E., Takeda K., Nurwidya F., Yoshioka Y., et al. (2013). Chronic intermittent hypoxia/reoxygenation facilitate amyloid-β generation in mice. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 37, 325–333. 10.3233/JAD-130419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M., Campillo N., Nonaka P. N., Montserrat J. M., Gozal D., Martínez-García M. A., et al. (2018). Aging reduces intermittent hypoxia-induced lung carcinoma growth in a mouse model of sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1164/rccm.201805-0892LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M., Laguna-Barraza R., Dalmases M., Calle A., Pericuesta E., Montserrat J. M., et al. (2014). Male fertility is reduced by chronic intermittent hypoxia mimicking sleep apnea in mice. Sleep 37, 1757–1765. 10.5665/sleep.4166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M., Rojas M., Campillo N., Cardenes N., Montserrat J. M., Navajas D., et al. (2015). Parabiotic model for differentiating local and systemic effects of continuous and intermittent hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 118, 42–47. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00858.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]