Abstract

Objective

To examine whether regional practice patterns impact racial/ethnic differences in intensity of end‐of‐life care for cancer decedents.

Data Sources

The linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare database.

Study Design

We classified hospital referral regions (HRRs) based on mean 6‐month end‐of‐life care expenditures, which represented regional practice patterns. Using hierarchical generalized linear models, we examined racial/ethnic differences in the intensity of end‐of‐life care across levels of HRR expenditures.

Principal Findings

There was greater variation in intensity of end‐of‐life care among Hispanics, Asians, and whites in high‐expenditure HRRs than in low‐expenditure HRRs.

Conclusions

Local practice patterns may influence racial/ethnic differences in end‐of‐life care.

Keywords: Racial differences, end‐of‐life care, regional practice patterns, geographic variation

Racial differences in health care utilization in the United States have been extensively documented. Minority patients usually receive poorer quality of care across a wide range of diseases and clinical settings (IOM 2003). To eliminate racial differences and improve quality of care among individuals from minority groups, it is crucial to identify drivers that lead to racial differences in health care. In one conceptual framework (Kelley et al. 2010), patient and physician medical decisions in end‐of‐life care are influenced by patient and family preferences, patient financial access to care (Kelley et al. 2011), local clinical practice norms, individual physicians’ clinical practice tendencies, and the regional supply of medical resources (Barnato et al. 2012). This framework may suggest key factors that could drive racial differences in end‐of‐life care.

We examined the role of regional practice patterns in relation to racial differences in end‐of‐life care. We used regional‐level expenditures as a proxy for regional practice patterns. Physician decisions account for 80–90 percent of health care spending (Eisenberg 1985; Crosson 2009). The geographic variation in health care utilization and expenditures may be driven primarily by regional patterns in physician practices (Sirovich et al. 2005, 2008) and to a much lesser extent by patient demographics, severity of underlying illness, and patient preferences (Eisenberg 1985; Barnato et al. 2007; Zuckerman et al. 2010).

End‐of‐life care is an excellent context for studying the relationship between regional practice patterns and racial differences in health care service utilization. Hospice use and end‐of‐life care differ substantially by race/ethnicity (Kagawa‐Singer and Blackhall 2001; LoPresti, Dement, and Gold 2016). Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients with advanced cancer are more likely to receive more aggressive end‐of‐life care and less likely to use hospice services than non‐Hispanic white patients (Smith, Earle, and McCarthy 2009; Miesfeldt et al. 2012). However, factors underlying disparities in the use of palliative care are not well understood (Johnson 2013).

We hypothesize that racial/ethnic differences in aggressive end‐of‐life care vary by region‐specific practice patterns. In low‐expenditure areas where hospice care is especially common and aggressive care is relatively uncommon, physicians may communicate the benefits of hospice/palliative care more consistently to patients of all racial/ethnic groups. Hence, patients are more likely to receive hospice care regardless of their racial/ethnic background and individual preferences. In high‐expenditure areas where aggressive care is relatively more common and hospice use less common, diversity in patient preferences may result in greater variation in hospice use and aggressive care.

Methods

Data and Study Design

We identified cancer decedents from the SEER‐Medicare database. The utilization of health services and the corresponding expenditures were derived from Medicare claims. Because of no involvement of human subject, the University Human Investigation Committee determined this study exempt from review.

Patients

The sample contained Medicare fee‐for‐service beneficiaries with breast, prostate, lung, colorectal, pancreas, liver, kidney, melanoma, or hematological cancer diagnosed between 2004 and 2011 and who died within 3 years of diagnosis as a result of cancer before 2012. We limited our sample to beneficiaries aged 66.5–94.9 years at death who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B during the last 18 months of life. Patients were excluded if their cancer diagnosis was based solely on death certificates or autopsy, they could not be assigned to a hospital referral region (HRR), they lived <6 months after cancer diagnosis, or if their race/ethnicity was not categorized as non‐Hispanic white (hereafter, “white”), African American (hereafter, “black”), Hispanic, or Asian. The stepwise ascertainment of our cohort is listed in Table S1.

Estimation of Medicare Spending

We used Medicare claims of cancer decedents for medical equipment and inpatient, outpatient, physician, home health, and hospice services during the last 6 months before death to estimate end‐of‐life care expenditures. Expenditures were adjusted for price inflation and expressed in 2011 U.S. dollars (CMS 2013). We assigned beneficiaries to HRRs based on their personal zip codes and calculated the mean of adjusted 6‐month end‐of‐life expenditures for each HRR. We excluded HRRs with fewer than 20 decedents from the models and winsorized data by truncating the end‐of‐life expenditures in our sample at the upper 97th percentile (Jha et al. 2009; Adams et al. 2010). HRRs were classified into low (quartile 1), intermediate (quartiles 2 and 3), or high (quartile 4) expenditures (Nicholas et al. 2011). We did not use the Dartmouth Atlas end‐of‐life spending index, which sampled all decedents (Dartmouth Institute 2016) because we focused on cancer decedents. Physicians in different specialties within an HRR were not equally aggressive in treating Medicare patients (Newhouse and Garber 2013).

Measurement

Outcomes

For each decedent, we assessed health care expenditures in the last month of life, hospice use within the last 6 months, and any aggressive end‐of‐life care. We defined any aggressive end‐of‐life care as the occurrence of at least one of the following: (1) ≥1 intensive care unit (ICU) admission within 30 days of death; (2) >1 hospitalization within 30 days of death; (3) >1 emergency department (ED) visit within 30 days of death; and (4) in‐hospital death (Earle et al. 2003).

Key Independent Variables

In addition to level of HHR expenditures, individual‐level race/ethnicity, that is, white, Hispanic, black, and Asian, was included (Bach et al. 2002).

Other Control Variables

We included as covariates patient age, gender, year of death, marital status, SEER registry, Medicaid enrollment, and metropolitan status of residence (Bach et al. 2002). We controlled for Elixhauser comorbidity conditions (Elixhauser et al. 1998) and a measure of disability status (Davidoff et al. 2013). Tumor characteristics included tumor site, advanced stage of cancer, multiple‐cancer diagnoses, and duration between cancer diagnosis and death. Ecological variables included median household income and percentage of adults with high school education or less, derived from merged census data.

Statistical Analysis

The unit of analysis was individual patient. We examined the bivariate associations between race/ethnicity and other patient and tumor characteristics. We assessed associations between HHR expenditures and sociodemographic and clinical variables with t‐tests for continuous variables and chi‐square tests for categorical variables. For each level of HHR expenditures, we calculated unadjusted average end‐of‐life expenditures by race/ethnicity and the proportion of decedents who received each indicator of intensive care.

In multivariable analyses, we constructed two‐level hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) with a logit link function and binary distribution, clustering patients by HRR. We included an interaction term between racial/ethnic group and HHR expenditure level to determine whether racial/ethnic differences varied by HHR expenditure level. We estimated the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) between minorities and whites for each HHR expenditure level. A two‐tailed p < .05 was used to define statistical significance. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Our sample included 102,759 beneficiaries. Compared with white patients, Hispanic and black patients were younger. Racial minority patients were significantly more likely to reside in metropolitan areas and HRRs with high end‐of‐life expenditures and to have multiple comorbidities and evidence of impaired functional status than white patients than white patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Decedents by Race

| Non‐Hispanic White N = 85,589 | African American N = 8,740 | p‐Value | Hispanic N = 4,759 | p‐Value | Asian N = 3,671 | p‐Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Medicare expenditures (SD) | 10,761 (12,349) | 12,841 (14,230) | <.001 | 13,605 (15,381) | <.001 | 15,388 (17,471) | <.001 |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 77.9 (7.0) | 76.3 (6.8) | <.001 | 76.9 (6.7) | <.001 | 77.9 (6.8) | <.001 |

| Expenditure level (%)a | |||||||

| Low | 27.0 | 18.8 | <.001 | 13.9 | <.001 | 3.5 | <.001 |

| Intermediate | 50.8 | 45.1 | 46.3 | 39.6 | |||

| High | 22.2 | 36.2 | 39.9 | 56.9 | |||

| Female (%) | |||||||

| No | 52.6 | 51.5 | 0.06 | 53.2 | 0.45 | 56.1 | <.001 |

| Yes | 47.4 | 48.5 | 46.8 | 43.9 | |||

| Marital status (%)a | |||||||

| Married | 53.0 | 35.1 | <.001 | 48.4 | <.001 | 62.6 | <.001 |

| Unmarried | 42.3 | 60.1 | 46.5 | 33.8 | |||

| Unknown | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 4.7 | |||

| Metro (%) | |||||||

| Metro | 80.4 | 87.7 | <.001 | 91.4 | <.001 | 95.9 | <.001 |

| Nonmetro/unknown | 19.6 | 12.3 | 8.6 | 4.1 | |||

| Income (%)a , b | |||||||

| <$33,000 | 20.2 | 53.6 | <.001 | 33.8 | <.001 | 17.6 | <.001 |

| $33,000–$39,999 | 16.2 | 15.1 | 15.7 | 10.6 | |||

| $40,000–$49,999 | 20.7 | 16.0 | 21.0 | 19.5 | |||

| $50,000–$62,999 | 20.0 | 8.8 | 16.1 | 22.4 | |||

| ≥$63,000 | 22.8 | 6.5 | 13.3 | 29.9 | |||

| High school education or less (%)a , b | |||||||

| <30% | 22.5 | 7.0 | <.001 | 13.1 | <.001 | 27.3 | <.001 |

| 30–39% | 16.1 | 8.3 | 11.5 | 18.0 | |||

| 40–49% | 17.9 | 11.3 | 15.9 | 18.1 | |||

| 50–59% | 18.6 | 20.2 | 17.7 | 16.9 | |||

| ≥60% | 24.7 | 53.2 | 41.8 | 19.8 | |||

| Medicaid (%) | |||||||

| No | 86.6 | 58.8 | <.001 | 50.6 | <.001 | 46.6 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 13.4 | 41.2 | 49.4 | 53.4 | |||

| Comorbidity (%) | |||||||

| None | 23.0 | 21.4 | <.001 | 21.9 | <.001 | 21.3 | <0.001 |

| 1–2 | 40.6 | 36.4 | 38.6 | 44.1 | |||

| More than 3 | 36.4 | 42.2 | 39.5 | 34.6 | |||

| Disability status (%) | |||||||

| No | 93.8 | 79.7 | <.001 | 77.7 | <.001 | 78.2 | <.001 |

| Yes | 6.2 | 20.3 | 22.3 | 21.8 | |||

| Tumor site (%)a | |||||||

| Breast | 7.3 | 10.1 | <.001 | 7.5 | <.001 | 4.8 | <.001 |

| Prostate | 6.8 | 10.7 | 8.6 | 4.8 | |||

| Lung | 42.0 | 39.4 | 30.5 | 37.9 | |||

| Colorectal | 14.2 | 16.8 | 17.8 | 15.3 | |||

| Pancreas | 7.0 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 8.9 | |||

| Liver | 2.0 | 2.4 | 6.4 | 11.6 | |||

| Kidney | 3.3 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 2.7 | |||

| Skin | 4.4 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.7 | |||

| Hematological cancer | 12.8 | 10.5 | 15.1 | 13.4 | |||

| Stage IV at diagnosis (%) | |||||||

| Not stage IV | 69.1 | 68.0 | 0.05 | 67.7 | 0.04 | 68.5 | 0.45 |

| Stage IV | 30.9 | 32.0 | 32.3 | 31.5 | |||

| Multiple cancers (%) | |||||||

| No | 87.7 | 88.1 | 0.24 | 89.8 | <.001 | 91.3 | <.001 |

| Yes | 12.3 | 11.9 | 10.2 | 8.7 | |||

| Time since cancer diagnosisa | |||||||

| 6 months–1 year | 39.8 | 39.9 | 0.68 | 39.4 | 0.01 | 39.5 | 0.19 |

| 1–2 years | 40.0 | 39.5 | 38.8 | 39.6 | |||

| 2–3 years | 20.3 | 20.6 | 21.9 | 20.9 | |||

Note: A sample of 102,759 cancer decedents was identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare dataset. Non‐Hispanic whites were used as the reference group for the statistical analyses.

Numbers may not sum up to 100 due to rounding.

SEER‐Medicare provides census‐based estimates of median household income and percentage of adults with high school education or less at the zip code level.

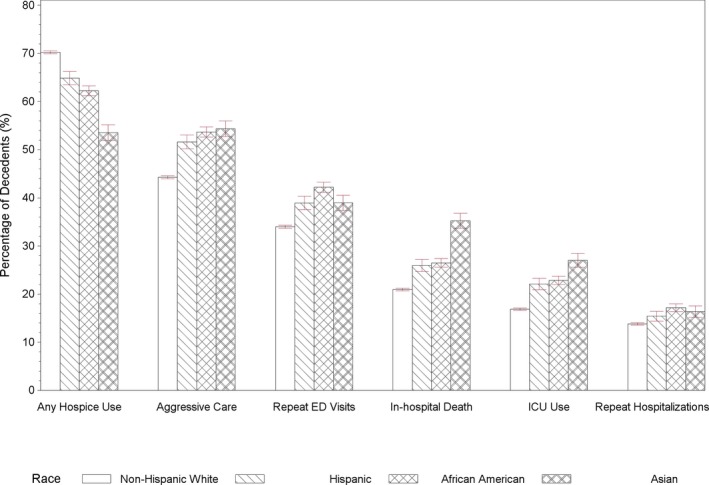

The utilization of end‐of‐life care differed across racial/ethnic groups (Figure 1). Hospice use was highest among white patients (70.2 percent), next most common in Hispanic (64.9 percent) and black patients (62.2 percent), and lowest in Asian patients (53.5 percent). Racial minorities were significantly more likely than whites to receive aggressive end‐of‐life care.

Figure 1.

- Notes: The measure of any aggressive care was defined as the occurrence of at least one of aggressive end‐of‐life care: (1) ≥1 intensive care unit (ICU) admission within 30 days of death; (2) >1 hospitalization within 30 days of death; (3) >1 emergency department (ED) visit within 30 days of death; and (4) in‐hospital death. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Mean end‐of‐life care expenditures for cancer decedents in our sample increased in parallel to the levels of overall Medicare end‐of‐life expenditures for their HRRs (Table 2). Hospice use was inversely associated and aggressive care was positively associated with level of overall HRR expenditures. Racial minorities were more likely to reside in HHRs with higher levels of expenditures.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Decedents by Level of Regional Mean End‐of‐Life Expenditures

| Low N = 25,559 | Intermediate N = 51,039 | High N = 26,161 | p‐Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Medicare expenditures (SD) | 8,386 (9,748) | 10,792 (12,091) | 14,812 (16,041) | <.001 |

| Hospice use (%) | ||||

| No | 27.2 | 30.3 | 37.2 | <.001 |

| Yes | 72.8 | 69.7 | 62.8 | |

| Any aggressive care (%) | ||||

| No | 60.0 | 55.1 | 47.1 | <.001 |

| Yes | 40.0 | 44.9 | 52.9 | |

| ICU use (%) | ||||

| No | 88.1 | 82.6 | 75.3 | <.001 |

| Yes | 11.9 | 17.4 | 24.7 | |

| Repeated hospitalizations (%) | ||||

| No | 87.5 | 86.4 | 82.8 | <.001 |

| Yes | 12.5 | 13.6 | 17.2 | |

| Repeated ED visits (%) | ||||

| No | 68.8 | 65.1 | 60.7 | <.001 |

| Yes | 31.2 | 34.9 | 39.3 | |

| In‐hospital death (%) | ||||

| No | 81.4 | 79.0 | 72.1 | <.001 |

| Yes | 18.6 | 21.0 | 27.9 | |

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 77.3 (6.9) | 77.7 (7.0) | 78.2 (7.0) | <.001 |

| Race (%)a | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 91.6 | 84.0 | 74.0 | <.001 |

| African American | 5.7 | 8.2 | 11.8 | |

| Hispanic | 2.5 | 4.4 | 7.2 | |

| Asian | 0.3 | 3.4 | 6.9 | |

| Female (%) | ||||

| No | 54.7 | 52.7 | 50.8 | <.001 |

| Yes | 45.3 | 47.3 | 49.2 | |

| Marital status (%)a | ||||

| Married | 54.2 | 51.2 | 49.7 | <.001 |

| Unmarried | 41.7 | 43.8 | 45.4 | |

| Unknown | 4.1 | 5.0 | 4.8 | |

| Metro (%) | ||||

| Metro | 54.6 | 86.2 | 99.7 | <.001 |

| Nonmetro/unknown | 45.4 | 13.8 | 0.3 | |

| Income (%)a , b | ||||

| <$33,000 | 39.9 | 20.9 | 13.5 | <.001 |

| $33,000–$39,999 | 26.0 | 15.1 | 8.0 | |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 19.6 | 21.9 | 17.7 | |

| $50,000–$62,999 | 10.1 | 22.4 | 20.5 | |

| ≥$63,000 | 4.4 | 19.8 | 40.3 | |

| High school education or less (%)a , b | ||||

| <30% | 11.0 | 20.4 | 31.4 | <.001 |

| 30–39% | 11.6 | 16.2 | 17.1 | |

| 40–49% | 14.6 | 18.6 | 17.1 | |

| 50–59% | 21.6 | 18.8 | 15.6 | |

| ≥60% | 41.3 | 26.0 | 18.8 | |

| Medicaid (%) | ||||

| No | 81.6 | 82.1 | 78.9 | <.001 |

| Yes | 18.4 | 17.9 | 21.1 | |

| Comorbidity (%)a | ||||

| None | 24.5 | 23.1 | 20.2 | <.001 |

| 1–2 | 41.6 | 40.5 | 38.5 | |

| More than 3 | 33.8 | 36.3 | 41.3 | |

| Disability status (%) | ||||

| No | 91.5 | 91.7 | 90.3 | <.001 |

| Yes | 8.5 | 8.3 | 9.7 | |

| Tumor site (%)a | ||||

| Breast | 7.0 | 7.4 | 7.9 | <.001 |

| Prostate | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.8 | |

| Lung | 43.2 | 41.7 | 37.9 | |

| Colorectal | 14.3 | 14.3 | 15.6 | |

| Pancreas | 6.0 | 7.2 | 7.9 | |

| Liver | 1.8 | 2.6 | 3.4 | |

| Kidney | 3.5 | 3.3 | 2.9 | |

| Skin | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | |

| Hematological cancer | 12.8 | 12.3 | 13.5 | |

| Stage IV at diagnosis (%) | ||||

| Not stage IV | 70.1 | 68.7 | 68.2 | <.001 |

| Stage IV | 29.9 | 31.3 | 31.8 | |

| Multiple cancers (%) | ||||

| No | 88.3 | 87.9 | 87.9 | .26 |

| Yes | 11.7 | 12.1 | 12.1 | |

| Time since cancer diagnosis (%)a | ||||

| 7 months to 1 year | 40.3 | 39.9 | 38.8 | <.001 |

| 1–2 years | 39.8 | 39.9 | 39.9 | |

| 2–3 years | 19.8 | 20.2 | 21.3 | |

Notes: A sample of 102,759 cancer decedents was identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare dataset. Low‐, intermediate‐, and high‐expenditure areas were classified based on the mean of adjusted 6‐month end‐of‐life expenditures for each HRR. Based on quartiles of expenditures, quartile 1 HRRs were classified as low‐expenditure areas, quartiles 2 and 3 HRRs as intermediate‐expenditure areas, and quartile 4 HRRs as high‐expenditure areas. p‐values are based on the statistic analyses of the differences between the low‐ and high‐expenditure areas.

Numbers may not sum up to 100 due to rounding.

SEER‐Medicare provides census‐based estimates of median household income and percentage of adults with high school education or less at the zip code level.

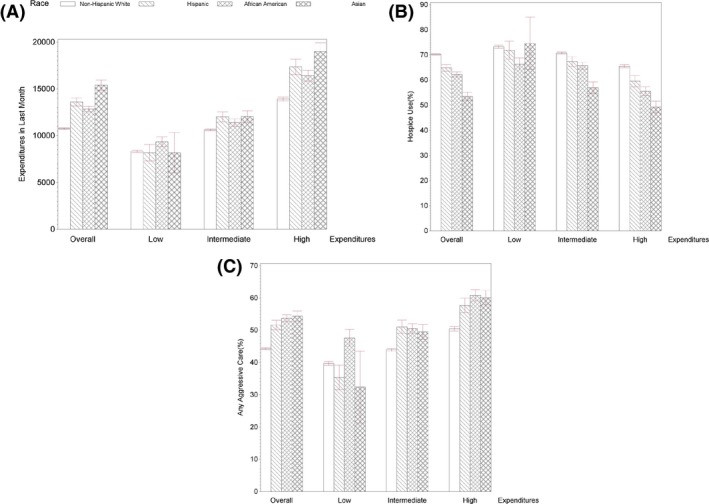

End‐of‐life care expenditures for cancer decedents differed significantly across racial/ethnic groups, ranging from $10,800 for whites to $15,400 for Asians (Figure 2). The patterns of racial differences also varied by level of HHR expenditures. In low‐expenditure areas, blacks had significantly higher end‐of‐life care expenditures than whites and Hispanics while no significant difference among whites, Hispanics and Asians were found. In contrast, in high‐expenditure areas, Asians had the highest expenditures, followed by Hispanics and blacks, and whites had the lowest expenditures.

Figure 2.

- Notes: Low‐, intermediate‐, and high‐expenditure areas were classified based on the mean of adjusted 6‐month end‐of‐life expenditures for each HRR. Based on quartiles of expenditures, quartile 1 HRRs were classified as low‐expenditure areas, quartiles 2 and 3 HRRs as intermediate‐expenditure areas, and quartile 4 HRRs as high‐expenditure areas. The measure of any aggressive care was defined as the occurrence of at least one of aggressive end‐of‐life care: (1) ≥1 intensive care unit (ICU) admission within 30 days of death; (2) >1 hospitalization within 30 days of death; (3) >1 emergency department (ED) visit within 30 days of death; and (4) in‐hospital death. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

The unadjusted analyses of intensity of end‐of‐life care showed similar results (Figure 2). In low‐expenditure areas, blacks were significantly less likely to use hospice services than whites and Hispanics; they were significantly more likely to receive aggressive end‐of‐life care than whites, Hispanics, and Asians. Notably, Hispanics were less likely than whites to receive aggressive care (p = .03). However, in high‐expenditure areas, hospice use was highest in white patients and lowest in Asian patients. Whites were significantly less likely to receive aggressive end‐of‐life care than Hispanics, Asians, and blacks. The patterns of racial differences in individual aggressive end‐of‐life care measured across the three expenditure areas were similar to the patterns of any aggressive end‐of‐life care (see Figure S1).

Consistent with the results from the unadjusted analyses, the interaction between race/ethnicity and level of HHR expenditures was significantly associated with hospice use and intensity of end‐of‐life care in multivariable analyses (Table 3). In low‐expenditure areas, compared with whites and Hispanics, black patients were significantly less likely to use hospice and more likely to receive aggressive end‐of‐life care. There was no significant difference between white and Hispanics or Asians. In high‐expenditure areas, racial differences in hospice use were significant larger than in low‐expenditure areas. White patients used hospice the most, followed by Hispanic patients and then black patients, with Asian patients using hospice the least. In high‐expenditure areas, Asian and black patients were most likely to receive aggressive end‐of‐life care and white patients were least likely. Sensitivity analyses in which HRRs were classified according to the last 1‐month end‐of‐life care expenditures showed qualitatively similar results (see Table S3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) for Racial Differences in Hospice Use and End‐of‐Life Care Intensity by Level of Regional End‐of‐Life Expenditures

| Low‐Expenditure Areas | Intermediate‐Expenditure Areas | High‐Expenditure Areas | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non‐Hispanic White | African America | Hispanic | Asian | Non‐Hispanic White | African American | Hispanic | Asian | Non‐Hispanic White | African American | Hispanic | Asian | |

| Hospice use | ||||||||||||

| AOR | Ref | 0.75 (0.66, 0.84) | 0.94a (0.79, 1.13) | 0.86 (0.50, 1.48) | Ref | 0.88 (0.82, 0.95) | 0.90 (0.82, 0.99) | 0.53 b (0.48, 0.58) | Ref | 0.75 (0.69, 0.81) | 0.86 a (0.78, 0.96) | 0.54 b (0.49, 0.60) |

| Any aggressive care | ||||||||||||

| AOR | Ref | 1.28 (1.15, 1.43) | 0.85b (0.72, 1.01) | 0.87 (0.52, 1.44) | Ref | 1.19 (1.12, 1.28) | 1.25 (1.15, 1.37) | 1.32 (1.20, 1.45) | Ref | 1.36 (1.25, 1.47) | 1.20 b (1.09, 1.33) | 1.41 (1.28, 1.57) |

Notes: Low‐, intermediate‐, and high‐expenditure areas were classified based on the mean of adjusted 6‐month end‐of‐life expenditures for each HRR. Based on quartiles of expenditures, quartile 1 HRRs were classified as low‐expenditure areas, quartiles 2 and 3 HRRs as intermediate‐expenditure areas, and quartile 4 HRRs as high‐expenditure areas. Adjusted hospice use (any aggressive use) was estimated using two‐level hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) with a logit link function and binary distribution. The model included interaction terms between racial/ethnic groups and three expenditure areas, as well as patient sociodemographic factors (i.e., patient age, gender, year of death, marital status, SEER registry, metropolitan status of residence, income and education) and disease factors (i.e., comorbidity, disability status, multiple‐cancer diagnoses, cancer duration, and tumor site). The measure of any aggressive care was defined as the occurrence of at least one of aggressive end‐of‐life care: (1) ≥1 intensive care unit (ICU) admission within 30 days of death; (2) >1 hospitalization within 30 days of death; (3) >1 emergency department (ED) visit within 30 days of death; and (4) in‐hospital death. Results of each aggressive end‐of‐life care are shown in Table S2. The bold values represent a significant difference between racial minorities and non‐Hispanic white patients in the same expenditure areas.

Statistically higher than African Americans in the same expenditure areas.

Significantly lower than African Americans in the same expenditure areas.

Discussion

We found that racial differences in intensity of end‐of‐life care for Medicare fee‐for‐service cancer decedents varied across areas with differing levels of mean end‐of‐life care expenditures. Specifically, Hispanic and Asian patients had end‐of‐life care patterns that were similar to white patients in low‐expenditure areas but received more aggressive end‐of‐life care than whites in high‐expenditure areas. Black patients were more likely than white patients to receive aggressive end‐of‐life care in all expenditure areas.

Our research provides several policy implications: First, approximately 25 percent of total Medicare annual spending is allocated to 5 percent of Medicare enrollees in their last year of life (Riley and Lubitz 2010). High health care expenditures are associated with aggressive end‐of‐life care, which is not consistent with patient preferences (Steinhauser et al. 2000; Barnato et al. 2007; Wright et al. 2008; O'Hare et al. 2010). We found that regional end‐of‐life care expenditures may play an important role in racial differences in hospice use and aggressive end‐of‐life care, suggesting that reducing regional end‐of‐life expenditures might decrease racial differences in health care utilization.

Second, system‐level factors may decrease racial differences in the intensity of end‐of‐life care. The level of mean regional expenditures is highly correlated with physician propensity for coordinating intensive care (Sirovich et al. 2005, 2008). Low‐expenditures regions may have adopted system‐level solutions to affect regional practice patterns, including care coordination, and changes in reimbursement structures. An integrated palliative care model and reduced fragmentation of care may decrease aggressive end‐of‐life care (Lawson et al. 2009; Frandsen et al. 2015). Government and health care administrators in high‐expenditure areas could adopt the approaches in the low‐expenditure areas to cultivate regional practice norms promoting hospice services.

Physicians often conform to their fellow physicians and hospital managers as they seek social approval from professional colleagues (Westert and Groenewegen 1999; de Jong et al. 2006). Physicians modify their practice styles to align with local practice patterns when they relocate to more or less aggressive care expenditure regions (Molitor 2018). When practicing in areas where hospice use is common, physicians may be more likely to persuade patients to receive less aggressive care. Such practice patterns might mitigate racial/ethnic differences in end‐of‐life care and reduce expenditures of the end‐of‐life care. Minority patients are disproportionately more likely to have misconceptions or little knowledge about hospice care (Kreling et al. 2010). Conversations among physicians, patients, and patients’ families critically affect the utilization of hospice care and end‐of‐life care decisions (Nielsen et al. 2010; Nedjat‐Haiem et al. 2013). Physicians could receive communication skills training to efficiently deliver information about treatment plans to patients of diverse racial/ethnic groups. These systemic changes could help minority patients accept hospice care and avoid aggressive end‐of‐life care.

Although our study suggests some variation in intensity of end‐of‐life care among whites, Hispanics, and Asians across levels of regional expenditures, black patients had consistently higher intensity of end‐of‐life care in all areas. Blacks may prefer life‐sustaining treatments for religious and spiritual reasons (Kypriotakis et al. 2014). Mistrust of the health care system by blacks also may add a barrier to hospice care (O'Mahony et al. 2008). We speculate that religiosity and mistrust may operate differently for blacks than for other minority groups. Future studies are warranted to examine whether coordinated system‐level interventions reduce the intensity of end‐of‐life care in black patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, we assumed patients with the same race/ethnicity had the same preferences for end‐of‐life care and we attributed differences in end‐of‐life care to regional practice patterns. Our study lacked direct measurement of patient preferences and system factors, such as care quality and caregiver availability. Further studies based on patient interviews or surveys are needed to identify whether patient preferences vary among the expenditure areas. Second, our sample population was limited to Medicare decedents who continuously enrolled in fee‐for‐service programs and died from one of nine types of cancer. Our results therefore may not be generalizable to other patients; for example, younger patients or patients with other types of cancer. Third, we used a retrospective approach to study racial differences in intensity of end‐of‐life care. Care received by confirmed decedents may not be comparable with care received by individuals who are predicted by care providers to be at the end of life (Bach, Schrag, and Begg 2004). In a prospective study of patients with a high probability of dying, blacks had consistently lower observed‐to‐expected ratios of intensity of end‐of‐life care than whites (Barnato et al. 2018). Finally, the race/ethnicity data in SEER have not been externally validated. There were relatively few Asian patients in each HRR category, which reduced statistical power for comparisons involving them.

In conclusion, racial/ethnic differences in the intensity of end‐of‐life care and expenditures varied by regional level of expenditures. Regional practice patterns may influence racial difference in end‐of‐life care, especially among Asian, Hispanic, and white cancer decedents. Additionally, there were persistent differences between blacks and whites in end‐of‐life care across levels of regional expenditures. Incentives or informational programs to promote less aggressive care may be particularly helpful in attenuating racial/ethnic differences and improving the quality of end‐of‐life care. Efforts to understand patient preferences and promote regional practice norms of patient‐centered care are also imperative.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Figure S1: Racial Differences in Repeat ED Visits (A), In‐Hospital Death (B), ICU Use (C), and Repeat Hospitalization (D) by Level of Regional Mean End‐of‐Life Expenditures.

Table S1: Stepwise Ascertainment of Study Cohort.

Table S2: Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) Examining Racial Differences in Aggressive End‐of‐Life Care by Level of Regional Six‐Month End‐of‐Life Expenditures.

Table S3: Sensitivity Analyses: Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) Examining Racial Differences in Hospice Use and End‐of‐Life Care Intensity by Level of Regional One‐Month End‐of‐Life Expenditures.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This investigation was supported by a pilot grant from the Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center and a P30 grant for the Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA016359). Dr. Wang is supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality career development award (K01 HS023900). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures: Dr. Wang receives research support from Genentech. Dr. Gross receives support from Medtronic, Inc., Johnson & Johnson, Inc., and 21st Century Oncology. Dr. Ma was a consultant for Celgene Corp. and Incyte Corp. These sources of support were not used for any portion of the current manuscript. None of the other coauthors have conflict of interests to report.

Disclaimer: None.

References

- Adams, J. L. , Mehrotra A., Thomas J. W., and McGlynn E. A.. 2010. “Physician Cost Profiling–Reliability and Risk of Misclassification.” New England Journal of Medicine 362 (11): 1014–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach, P. B. , Schrag D., and Begg C. B.. 2004. “Resurrecting Treatment Histories of Dead Patients: A Study Design That Should Be Laid to Rest.” Journal of the American Medical Association 292 (22): 2765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach, P. B. , Guadagnoli E., Schrag D., Schussler N., and Warren J. L.. 2002. “Patient Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics in the SEER‐Medicare Database Applications and Limitations.” Medical Care 40 (8 Suppl): IV‐19‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato, A. E. , Herndon M. B., Anthony D. L., Gallagher P. M., Skinner J. S., Bynum J. P., and Fisher E. S.. 2007. “Are Regional Variations in End‐of‐Life Care Intensity Explained by Patient Preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population.” Medical Care 45 (5): 386–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato, A. E. , Tate J. A., Rodriguez K. L., Zickmund S. L., and Arnold R. M.. 2012. “Norms of Decision Making in the ICU: A Case Study of Two Academic Medical Centers at the Extremes of End‐of‐Life Treatment Intensity.” Intensive Care Medicine 38 (11): 1886–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato, A. E. , Chang C. H., Lave J. R., and Angus D. C.. 2018. “The Paradox of End‐of‐Life Hospital Treatment Intensity Among Black Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 21 (1): 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CMS . 2013. “Market Basket Data [Database Online]” [accessed on June 9, 2013]. Available at http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/MarketBasketData.html

- Crosson, F. J. 2009. “Change the Microenvironment. Delivery System Reform Essential to Control Costs.” Modern Healthcare 39 (17): 20–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartmouth Institute . 2016. “Total Medicare Reimbursements per Decedent” [accessed on February 8, 2018]. Available at http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/table.aspx?ind=23&tf=35&ch=5&loc=&loct=3&fmt=45

- Davidoff, A. J. , Zuckerman I. H., Pandya N., Hendrick F., Ke X., Hurria A., Lichtman S. M., Hussain A., Weiner J. P., and Edelman M. J.. 2013. “A Novel Approach to Improve Health Status Measurement in Observational Claims‐Based Studies of Cancer Treatment and Outcomes.” Journal of Geriatric Oncology 4 (2): 157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle, C. C. , Park E. R., Lai B., Weeks J. C., Ayanian J. Z., and Block S.. 2003. “Identifying Potential Indicators of the Quality of End‐of‐Life Cancer Care from Administrative Data.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 21 (6): 1133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, J. M. 1985. “Physician Utilization: The State of Research about Physicians’ Practice Patterns.” Medical Care 23 (5): 461–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser, A. , Steiner C., Harris D. R., and Coffey R. M.. 1998. “Comorbidity Measures for Use with Administrative Data.” Medical Care 36 (1): 8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen, B. R. , Joynt K. E., Rebitzer J. B., and Jha A. K.. 2015. “Care Fragmentation, Quality, and Costs among Chronically Ill Patients.” American Journal of Managed Care 21 (5): 355–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (Full Printed Version). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha, A. K. , Orav E. J., Dobson A., Book R. A., and Epstein A. M.. 2009. “Measuring Efficiency: The Association of Hospital Costs and Quality of Care.” Health Affairs (Millwood) 28 (3): 897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. S. 2013. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Palliative Care.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 16 (11): 1329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, J. D. , Westert G. P., Lagoe R., and Groenewegen P. P.. 2006. “Variation in Hospital Length of Stay: Do Physicians Adapt Their Length of Stay Decisions to What Is Usual in the Hospital Where They Work?” Health Services Research 41 (2): 374–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa‐Singer, M. , and Blackhall L. J.. 2001. “Negotiating Cross‐Cultural Issues at the End of Life: “You Got to Go Where He Lives”.” Journal of the American Medical Association 286 (23): 2993–3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, A. S. , Morrison R. S., Wenger N. S., Ettner S. L., and Sarkisian C. A.. 2010. “Determinants of Treatment Intensity for Patients with Serious Illness: A New Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 13 (7): 807–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, A. S. , Ettner S. L., Morrison R. S., Du Q., Wenger N. S., and Sarkisian C. A.. 2011. “Determinants of Medical Expenditures in the Last 6 Months of Life.” Annals of Internal Medicine 154 (4): 235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreling, B. , Selsky C., Perret‐Gentil M., Huerta E. E., and Mandelblatt J. S.. 2010. “‘The Worst Thing About Hospice is That They Talk about Death’: Contrasting Hospice Decisions and Experience among Immigrant Central and South American Latinos with US‐Born White, Non‐Latino Cancer Caregivers.” Palliative Medicine 24 (4): 427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypriotakis, G. , Francis L. E., O'Toole E., Towe T. P., and Rose J. H.. 2014. “Preferences for Aggressive Care in Underserved Populations with Advanced‐Stage Lung Cancer: Looking beyond Race and Resuscitation.” Supportive Care in Cancer 22 (5): 1251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, B. J. , Burge F. I., McIntyre P., Field S., and Maxwell D.. 2009. “Can the Introduction of an Integrated Service Model to an Existing Comprehensive Palliative Care Service Impact Emergency Department Visits among Enrolled Patients?” Journal of Palliative Medicine 12 (3): 245–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoPresti, M. A. , Dement F., and Gold H. T.. 2016. “End‐of‐Life Care for People with Cancer from Ethnic Minority Groups: A Systematic Review.” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 33 (3): 291–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesfeldt, S. , Murray K., Lucas L., Chang C. H., Goodman D., and Morden N. E.. 2012. “Association of Age, Gender, and Race with Intensity of End‐of‐Life Care for Medicare Beneficiaries with Cancer.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 15 (5): 548–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molitor, D. 2018. “The Evolution of Physician Practice Styles: Evidence from Cardiologist Migration.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10 (1): 326–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedjat‐Haiem, F. R. , Carrion I. V., Lorenz K. A., Ell K., and Palinkas L.. 2013. “Psychosocial Concerns among Latinas with Life‐Limiting Advanced Cancers.” Omega (Westport) 67 (1–2): 167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse, J. P. , and Garber A. M.. 2013. “Geographic Variation in Medicare Services.” New England Journal of Medicine 368 (16): 1465–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, L. H. , Langa K. M., Iwashyna T. J., and Weir D. R.. 2011. “Regional Variation in the Association between Advance Directives and End‐of‐Life Medicare Expenditures.” Journal of the American Medical Association 306 (13): 1447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S. S. , He Y., Ayanian J. Z., Gomez S. L., Kahn K. L., West D. W., and Keating N. L.. 2010. “Quality of Cancer Care among Foreign‐Born and US‐Born Patients with Lung or Colorectal Cancer.” Cancer 116 (23): 5497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare, A. M. , Rodriguez R. A., Hailpern S. M., Larson E. B., and Kurella Tamura M.. 2010. “Regional Variation in Health Care Intensity and Treatment Practices for End‐Stage Renal Disease in Older Adults.” Journal of the American Medical Association 304 (2): 180–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony, S. , McHenry J., Snow D., Cassin C., Schumacher D., and Selwyn P. A.. 2008. “A Review of Barriers to Utilization of the Medicare Hospice Benefits in Urban Populations and Strategies for Enhanced Access.” Journal of Urban Health 85 (2): 281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley, G. F. , and Lubitz J. D.. 2010. “Long‐Term Trends in Medicare Payments in the Last Year of Life.” Health Services Research 45 (2): 565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirovich, B. E. , Gottlieb D. J., Welch H. G., and Fisher E. S.. 2005. “Variation in the Tendency of Primary Care Physicians to Intervene.” Archives of Internal Medicine 165 (19): 2252–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirovich, B. , Gallagher P. M., Wennberg D. E., and Fisher E. S.. 2008. “Discretionary Decision Making by Primary Care Physicians and the Cost of U.S. Health Care.” Health Affairs (Millwood) 27 (3): 813–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. K. , Earle C. C., and McCarthy E. P.. 2009. “Racial and Ethnic Differences in End‐of‐Life Care in Fee‐for‐Service Medicare Beneficiaries with Advanced Cancer.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57 (1): 153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser, K. E. , Clipp E. C., McNeilly M., Christakis N. A., McIntyre L. M., and Tulsky J. A.. 2000. “In Search of a Good Death: Observations of Patients, Families, and Providers.” Annals of Internal Medicine 132 (10): 825–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westert, G. P. , and Groenewegen P. P.. 1999. “Medical Practice Variations: Changing the Theoretical Approach.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 27 (3): 173–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. A. , Zhang B., Ray A., Mack J. W., Trice E., Balboni T., Mitchell S. L., Jackson V. A., Block S. D., Maciejewski P. K., and Prigerson H. G.. 2008. “Associations Between End‐of‐Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment.” Journal of the American Medical Association 300 (14): 1665–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, S. , Waidmann T., Berenson R., and Hadley J.. 2010. “Clarifying Sources of Geographic Differences in Medicare Spending.” New England Journal of Medicine 363 (1): 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Figure S1: Racial Differences in Repeat ED Visits (A), In‐Hospital Death (B), ICU Use (C), and Repeat Hospitalization (D) by Level of Regional Mean End‐of‐Life Expenditures.

Table S1: Stepwise Ascertainment of Study Cohort.

Table S2: Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) Examining Racial Differences in Aggressive End‐of‐Life Care by Level of Regional Six‐Month End‐of‐Life Expenditures.

Table S3: Sensitivity Analyses: Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) Examining Racial Differences in Hospice Use and End‐of‐Life Care Intensity by Level of Regional One‐Month End‐of‐Life Expenditures.