Abstract

Background:

Diabetes distress has been linked with suboptimal glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. We evaluated the effect of diabetes distress on self-management behaviors in patients using insulin pumps.

Methods:

We analyzed the impact of diabetes distress on self-management behaviors using pump downloads from 129 adults treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) at a single hospital clinic. Exclusion criteria were CSII treatment <6 months, pregnancy, hemoglobinopathy, and continuous glucose monitoring/sensor use. People were categorized into three groups based on the Diabetes Distress Scale-2 (DDS-2) score: < 2.5, 2.5-3.9, > 4.

Results:

Participants had a mean age of 45.2 ± 19.0 years; duration of diabetes 26.6 ± 16.2 years; duration of CSII 6.0 ± 3.5 years; HbA1c 8.0 ± 1.2%; and DDS-2 score 2.7 ± 1.3. Self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG) frequency and bolus wizard usage was similar between groups. Patients with higher distress had higher HbA1c (7.7 ± 0.9 vs. 8.0 ± 0.9 vs. 8.7 ± 1.8; P = 0.004), lower frequency of set changes (4.7 ± 1.3vs. 4.8 ± 1.9 vs. 3.8 ± 1.1; P = .025), a greater number of appointments booked (5.8 ± 4.4 vs. 8.6 ± 4.8 vs. 8.1 ± 6.9; P = .021), and a greater number of appointments missed (1.9 ± 1.3 vs. 2.5 ± 1.5 vs. 3.8 ± 4.1; P = .004).

Conclusions:

Although in some patients, high distress may be caused by reduced self-management, in our highly trained, pump-using patients, high distress was associated with suboptimal biomedical outcomes despite appropriate self-management behaviors. Future work should further explore the relationships between diabetes distress, self-management, and glycemic control.

Keywords: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, distress, pump, self-management, self-monitoring blood glucose, type 1

Current National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommendations advise that patients are supported to achieve a HbA1c of under 6.5%. However, despite progress in diabetes management, only 7.5% of patients achieve this target.1 Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) therapy, delivered through insulin pumps is offered to patients who are unable to meet HbA1c targets on conventional multiple daily injection (MDI) therapy. However, despite the practical advantages, the HbA1c outcomes remain disappointing, with a reported absolute difference of 0.3%.2 Moreover, in audits comparing HbA1c in patients before and after pump use, 61% of patients still had a HbA1c of above 58 mmol/mol (>7.5%) after pump use.3 Therefore, further investigation is needed to elucidate barriers to pump therapy and ways in which we can optimize its use.

Two of the factors identified to affect glycemic control in patients using insulin pumps are self-monitoring blood glucose frequency and bolus wizard usage.4-6 In patients using insulin pumps, each additional blood glucose test per day was associated with a 0.21% reduction in HbA1c.4 Furthermore, effective bolus wizard usage has been shown to lead to improvements in postprandial blood glucose levels and therefore, the number of bolus corrections needed.5 In addition, patients with lower HbA1c have been reported to use the bolus wizard more frequently than those with less optimal control.6

A potential barrier to engagement with these self-management behaviors is diabetes distress, which is defined as patient concerns about disease management, support, emotional burden, and access to care.7 High diabetes distress has been associated with suboptimal glycemic control both in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.8-10 A growing body of literature has shown that diabetes distress is more closely linked to poorer self-management and treatment outcomes compared with depression.8 However, most of these data are self-reported, with limited quantitative data available to support this. Furthermore, the majority of the literature focuses on patients with type 2 diabetes and data about self-management behaviors in type 1 diabetes are limited.

Few studies have quantified the relationship between diabetes distress and self-management behaviors in pump patients. Therefore, in this study we set out to explore the association between diabetes distress and various self-management behaviors including self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), bolus wizard usage, and health care utilization.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study of adults with type 1 diabetes, at a single hospital clinic, treated with CSII. We only included data available from Carelink software for participants who were using a Medtronic pump with a linked capillary blood glucose (CBG) meter. A minimum of 14 days of data available on pump downloads was required as well as a concurrent diabetes distress score and HbA1c recorded within the last 1 month. Exclusion criteria were CSII treatment <6 months, pregnancy, hemoglobinopathy, and continuous glucose monitoring/sensor use. A total of 129 patients met the inclusion criteria.

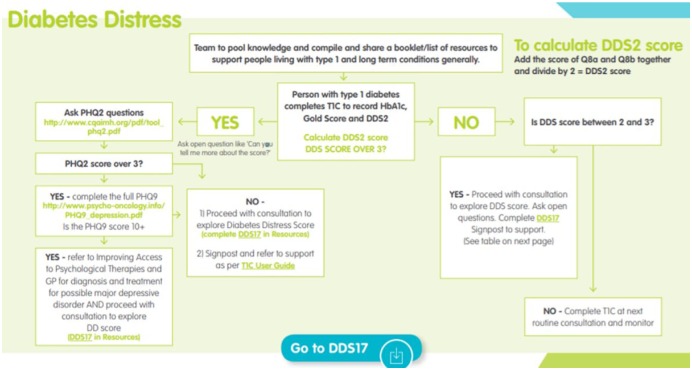

In our clinic, patients complete the Type 1 Consultation Tool (see Appendix A) prior to each appointment, which contains the Diabetes Distress Scale-2 (DDS-2) questionnaire, which then forms the basis of the consultation.11 Patient management is then determined by a pathway illustrated in Appendix B. Pumps are routinely downloaded using proprietary software. Data on SMBG frequency, manual boluses per day, bolus wizard events per day, proportion of boluses with wizard override and proportion given with food, average capillary blood glucose, capillary blood glucose standard deviation, and time within blood glucose target range were all extracted from the last available pump download with a concurrent DDS-2 score and HbA1c. The target range for CBG readings was defined as 4-10 mmol/l as per American Diabetes Association guidelines.12 Appointment data were also obtained for each patient from the Patient Information Management System.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS version 24. A one-way Analysis of Variance was carried out to assess between-group differences in baseline characteristics as well as self-management behaviors in patients with low, medium and high DDS-2. A chi-square test was used to compare between group differences in sex and proportion of patients who had undergone dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) training. A regression analysis was used to assess the predictive value of the various self-management behaviors on HbA1c. P values < .05 were considered significant.

Results

We analyzed data from a total of 129 adults (age, 45.2 ± 19.0 years; duration of diabetes, 26.6 ± 16.2 years; duration of CSII, 6.0 ± 3.5 years; HbA1c, 8.0 ± 1.2%, all values mean ± SD). Patients were categorized into low (DDS-2 score <2.5), moderate (DDS-2 score 2.5-3.9), and high (DDS-2 score ⩾4.0) distress groups, according to cut-offs proposed by Todd et al.13 The mean DDS-2 score across the cohort was 2.7 ± 1.3.

There were statistically significant between-group differences in HbA1c (P = .004) and sex (P = .019). Patients with higher diabetes distress had a higher HbA1c and a trend to higher CBG as well as lower proportion of readings in range. However, there was no difference in proportion of people who had undergone DAFNE training, or in the variability of CBG readings (Table 1). All other baseline characteristics were similar across groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Presented for Total Population, DDS-2 < 2.5, DDS-2 2.5-3.9, DDS-2 ⩾ 4.

| Total sample (N = 129) | DDS-2score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (< 2.5) (n = 59) | Moderate (2.5-3.9) (n = 46) |

High (> 4) (n = 24) | P value | ||

| Age (years) | 45.2 ± 19.0 | 44.3 ± 18.7 | 48.5 ± 21.4 | 40.1 ± 12.3 | .270 |

| Sex (% female) | 65.8 | 54.2 | 80.4 | 66.7 | .019 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 4.8 | 26.7 ± 4.5 | 26.6 ± 4.4 | 28.9 ± 5.8 | .191 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 26.6 ± 16.2 | 25.8 ± 16.7 | 28.3 ± 16.8 | 25.1 ± 13.9 | .673 |

| Duration of CSII (years) | 6.0 ± 3.5 | 5.8 ± 3.4 | 6.0. ± 3.6 | 6.3 ± 3.6 | .886 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.0 ± 1.2 | 7.7 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 8.7 ± 1.8 | .004 |

| Average CBG (mmol/L) | 10.0 ± 2.2 | 9.8 ± 2.1 | 9.8 ± 1.9 | 10.9 ± 2.6 | .079 |

| CBG standard deviation (mmol/L) | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | .774 |

| Time in range (%) | 47.0 ± 18.9 | 49.5 ± 19.3 | 47.9 ± 16.8 | 39.4 ± 20.5 | .083 |

| DAFNE trained (%) | 77.5 | 79.7 | 71.7 | 83.3 | .472 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

In terms of self-management behaviors, there were no differences in the frequency of SMBG or boluses, in the proportion of boluses given as manual bolus or with food, or in the use of the bolus wizard. Statistically significant between-group differences were found in frequency of set changes (indicated by number of tubing fills) (P = .025), number of appointments booked (P = .021) and number of appointments missed (P = .004) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-management Data Presented for Total Population, DDS-2 < 2.5, DDS-2 2.5-3.9, DDS-2 ⩾ 4.

| Total sample (N = 129) | DDS-2 score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low ( < 2.5) (n = 59) | Moderate (2.5-3.9) (n = 46) | High (> 4) (n = 24) |

P value | ||

| SMBG frequency (tests per day) | 5.2 ± 2.5 | 5.2 ± 2.7 | 5.4 ± 2.1 | 4.9 ± 2.7 | .753 |

| Total no. of boluses (per day) | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 5.7 ± 2.0 | 5.5 ± 2.0 | 5.2 ± 2.9 | .671 |

| No. of manual boluses (per day) | 0.59 ± 1.18 | 0.68 ± 1.34 | 0.51 ± 1.05 | 0.55 ± 1.04 | .753 |

| No. of bolus wizard events (per day) | 5.0 ± 2.4 | 5.0 ± 2.2 | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 4.7 ± 3.3 | .805 |

| Proportion of boluses using wizard (%) | 88.7 ± 22.5 | 88.1 ± 23.9 | 90.5 ± 19.5 | 86.7 ± 25.1 | .771 |

| Proportion of boluses with food (%) | 74.0 ± 20.2 | 73.2 ± 20.4 | 73.5 ± 21.5 | 76.7 ± 17.4 | .762 |

| Proportion of boluses with wizard override (%) | 13.2 ± 15.0 | 11.2 ± 12.1 | 14.0 ± 16.7 | 16.6 ± 17.6 | .295 |

| No. of tubing fills (per 14 days) | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | .025 |

| No. of appointments booked (per year) | 7.2 ± 5.2 | 5.8 ± 4.4 | 8.6 ± 4.8 | 8.1 ± 6.9 | .021 |

| No. of appointments missed (per year) | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 3.8 ± 4.1 | .004 |

| Proportion of appointments missed (%) | 31.9 ± 17.9 | 30.8 ± 19.7 | 29.4 ± 15.6 | 40.1 ± 15.8 | .073 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Multiple regression was used to assess the predictive value of the various self-management behaviors on HbA1c. The model gave an R2 value of .215 and SMBG frequency, number of boluses, and number of appointments attended were significant predictors of HbA1c (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Analysis Assessing the Predictive Value of Self-Management Behaviors on HbA1c.

| Variable | β | P value |

|---|---|---|

| SMBG frequency (per day) | −.223 | .040 |

| Total no. of boluses (per day) | −.356 | .000 |

| Proportion of boluses using wizard (%) | .028 | .777 |

| Proportion of boluses with food (%) | −.121 | .204 |

| Proportion of boluses with wizard override (%) | −.057 | .515 |

| No. of tubing fills (per 14 days) | .050 | .565 |

| Appointments attended (per year) | .190 | .027 |

Discussion

Our data confirmed the association between diabetes distress and glycemic control, as reported by previous studies.8,13 Patients with high diabetes distress had a significantly higher HbA1c as well as a lower time in normal blood glucose range.

Patients with medium and high distress performed significantly fewer set changes (as indicated by frequency of tubing fills), compared to those with low distress. The number of appointments missed was significantly greater in patients with higher distress, however these patients also booked more appointments. Patients with high distress had numerically lower boluses per day and a greater number of wizard overrides. However, these results failed to reach statistical significance, and despite the differences in HbA1c similar SMBG frequency, boluses per day, and bolus wizard usage were seen in patients with low, medium, and high distress.

Previous studies have suggested that high diabetes distress prevents patients from engaging in self-management behaviors and that this lack of self-management results in a higher HbA1c. High diabetes distress has been associated with a greater number of missed boluses,14 poorer adherence to meal planning recommendations and lower levels of exercise.15 High regimen-related distress specifically has also been associated with lower SMBG frequency.15 Therefore, in this study we expected that patients with high distress would have a lower SMBG frequency, lower number of boluses per day, less frequent set changes, suboptimal bolus wizard usage, and reduced contact with health care teams. Thus, it was surprising to see that in this study population, patients with higher distress achieved a higher HbA1c despite similar self-management behaviors.

It is possible that these results may be due to the differences between our study population and previous studies. Our patients were managed in a tertiary center and were in regular contact with health care professionals, as indicated by the high number of appointments. Those with high distress missed a greater number of appointments, which may be due to the increased burden of diabetes management perceived by these patients. These patients did however, have a greater number of appointments booked, which may reflect the efforts of the health care team to support them. Unlike previous studies, our patients were all receiving optimized treatment in the form of pump therapy. Moreover, a high proportion of these patients (78%) were DAFNE trained,16 so had received intensive education around carbohydrate counting and dose adjustment prior to pump therapy. Although high variability in CBG has been associated with Quality of Life,17 and could lead to high distress and high HbA1c despite adequate SMBG, this does not appear to be the case in our cohort, as the standard deviation of their CBG was similar.

The high level of support received by these patients may be responsible for increased adherence to self-management behaviors even in those with high diabetes distress, and thus may explain the absence of differences in self-management in patients with varying degrees of distress. Increased self-management in this patient group compared to the general population is evidenced by the SMBG frequency of 5.2 tests per day which is higher than the DAFNE recommendations of 4 tests per day.

In this study, diabetes distress was quantified using the DDS-2 questionnaire as this is routinely used in clinical care. Although the DDS-2 questionnaire showed a high level of association with the DDS-17,18 its brevity makes it impossible to ascertain the underlying causes of the patient’s distress. Thus, we are unable to determine if a fear of hypoglycemia, defensive eating or undercounting of carbohydrates may have contributed to the higher HbA1c. A more detailed questionnaire such as the DDS-17 or PAID questionnaires may be able to explore these possibilities.

The association between HbA1c and diabetes distress may be bidirectional in nature. Rather than diabetes distress leading to poorer self-management and subsequently, resulting in a higher HbA1c, suboptimal glycemic control may in fact be the main driver of diabetes distress in patients regardless of their self-management behaviors. Thus, patients may be monitoring their capillary blood glucose frequently and may adhere to self-management behaviors, and still have a high HbA1c and high CBG readings. This failure to achieve glycemic control may result in feelings of ‘diabetes burnout’ and increased diabetes distress, independent of adherence to self-management behaviors.

Current literature suggests that patients with type 1 diabetes are more likely to develop depression compared with the general population.19 However, this was not routinely screened for in our patients. Comorbid depression may also contribute to higher HbA1c, however this could not be quantified in this study. In addition, this study did not measure treatment satisfaction or accuracy of carbohydrate counting. In a previous study, Todd et al reported that 23% of patients with adequate glycemic control (HbA1c<58 mmol/L) had high diabetes distress,13 suggesting that in some patients distress may play an important role in maintaining self-management behaviors and achieving glycemic control.

Conclusion

Although in some patients, high distress may result in raised HbA1c through reduced self-management behaviors, in our highly trained pump-using patients we found that high distress was associated with suboptimal biomedical outcomes despite appropriate self-management behaviors. This suggests that although they were performing the tasks required for adequate diabetes control, there may be other factors that prevented our patients from achieving appropriate results. Future qualitative work should explore the relationships between diabetes distress, self-management, and glycemic control further.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Diaebtes staff who colelct the data used in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the South London Health Innovation Network who were instrumental in developing the T1C tool. For access to the tool please contact the authors.

Appendix

Appendix A.

The Type 1 Consultation Tool11.

Appendix B.

Diabetes Distress Management Pathway.11

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CBG, capillary blood glucose; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; DAFNE, dose adjustment for normal eating; DDS-2, Diabetes Distress Scale; MDI, multiple daily injection; NICE, National Institute of Clinical Excellence; PAID, problem areas in diabetes; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PC has received speaker fees and is on the advisory board for Medtronic, Roche, Omnipod, and Abbott

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Health and Social Care Information Centre. National Diabetes Audit—2012-2013: Report 1, Care Processes and Treatment Targets. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Misso ML, Egberts KJ, Page M, O’Connor D, Shaw J. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) versus multiple insulin injections for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(1):CD005103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hammond P, Liebl A, Grunder S. International survey of insulin pump users: impact of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy on glucose control and quality of life. Prim Care Diabetes. 2007;1(3):143-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matejko B, Skupien J, Mrozińska S, et al. Factors associated with glycemic control in adult type 1 diabetes patients treated with insulin pump therapy. Endocrine. 2015;48(1):164-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shashaj B, Busetto E, Sulli N. Benefits of a bolus calculator in pre- and postprandial glycaemic control and meal flexibility of paediatric patients using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII). Diabet Med. 2008;25(9):1036-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deeb A, Abu-Awad S, Abood S, et al. Important determinants of diabetes control in insulin pump therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(3):166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, Polonsky WH. Development of a brief diabetes distress screening instrument. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):246-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fisher L, Mullan JT, Arean P, Glasgow RE, Hessler D, Masharani U. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):23-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Indelicato L, Dauriz M, Santi L, et al. Psychological distress, self-efficacy and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27(4):300-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Strandberg RB, Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Peyrot M, Rokne B. Relationships of diabetes-specific emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and overall well-being with HbA1c in adult persons with type 1 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(3):174-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choudhary P, Sturt J, Patel N, Spratling L. Type 1 Consultation (T1C) Tool. Health Innovative Network; 2017. https://healthinnovationnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Type-1-Consultation-Tool-User-Guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(suppl 1):s11-s66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Todd PJ, Edwards F, Spratling L, et al. Evaluating the relationships of hypoglycaemia and HbA1c with screening-detected diabetes distress in type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab J. 2018;1(1):e00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hessler DM, Fisher L, Polonsky WH, et al. Diabetes distress is linked with worsening diabetes management over time in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2017;34(9):1228-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):626-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amiel SA, Beveridge S, Bradley C. Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325(7367):746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ayano-Takahara S, Ikeda K, Fujimoto S, et al. Glycemic variability is associated with quality of life and treatment satisfaction in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):e1-e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky WH, Mullan J. When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful? establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):259-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(suppl):S8-S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]