Abstract

Background:

Many people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) report barriers to using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Diabetes care providers may have their own barriers to promoting CGM uptake. The goal of this study was to develop clinician “personas” with regard to readiness to promote CGM uptake.

Methods:

Diabetes care providers who treat people with T1D (N = 209) completed a survey on perceived patient barriers to device uptake, technology attitudes, and characteristics and barriers specific to their clinical practice. K-means cluster analyses grouped the sample by CGM barriers and attitudes. ANOVAs and chi-square tests assessed group differences on provider and patient characteristics. The authors assigned descriptive names for each persona.

Results:

Analyses yielded three clinician personas regarding readiness to promote CGM uptake. Ready clinicians (20% of sample; 24% physicians, 38% certified diabetes educators/CDEs) had positive technology attitudes, had clinic time to work with patients using CGM, and found it easy to keep up with technology advances. In comparison, Cautious clinicians (41% of sample; 17% physicians, 53% CDEs) perceived that their patients had many barriers to adopting CGM and had less time than the Ready group to work with patients using CGM data. Not Yet Ready clinicians (40% of sample; 9% physicians; 79% CDEs) had negative technology attitudes and the least clinic time to work with CGM data. They found it difficult to keep up with technology advances.

Conclusion:

Some diabetes clinicians may benefit from tailored interventions and additional time and resources to empower them to help facilitate increased uptake of CGM technology.

Keywords: continuous glucose monitoring, device readiness, diabetes providers, technology attitudes, type 1 diabetes

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems are becoming a hallmark of type 1 diabetes (T1D) management in both pediatric and adult populations. CGM systems have been shown to improve glycemic control and reduce hypoglycemia1-3 and can also improve quality of life and treatment satisfaction.4-6 CGM technology has undergone significant improvements in accuracy and usability and newer models allow for sharing data with others,7,8 decision making without fingersticks,9 and other features to reduce burden and improve usability.10

Improvements in CGM technology have also helped enable advances in closed-loop technology.11 These systems have been shown to increase the time an individual spends in target glucose range, to reduce mean glucose level, and to decrease overnight hypoglycemia.12-15

To benefit from these major advances in technology to manage diabetes, individuals with T1D must be willing to wear an insulin pump and CGM on their bodies continuously. However, data from the T1D Exchange have shown that in the United States, CGM uptake rates lag behind that of insulin pumps, with between 6% and 20% wearing CGM compared to 54% to 61% using insulin pumps depending on age group.16,17 Insurance and cost are major barriers, followed by the hassle of wearing devices and disliking having devices on one’s body.18 Other barriers are concerns about accuracy, frequency and intrusiveness of alarms, and not wanting others to see the device and ask questions about it.18,19 These barriers may have an impact on the adoption of closed loop.20 Therefore, it is imperative to address these barriers to maximize the number of people with T1D who can gain benefit from these diabetes technology systems.

Diabetes care clinicians are instrumental in helping their patients to adopt new technology, to receive necessary education, and to overcome barriers and troubleshoot issues as they arise.21 At the same time, clinicians can also serve as gatekeepers to technology. Understanding clinician barriers to promoting uptake of new treatment technologies is important to help facilitate increased device uptake and sustained use. Provider characteristics and attitudes toward new treatments can influence their likelihood of offering them to patients. For example, physicians who believed insulin pens were effective and convenient were more likely to prescribe them over syringes.22 In addition, physicians who self-identify as “medical innovators” tended to hold more positive attitudes about inhaled insulin and endorsed a greater likelihood of prescribing it to their patients.23 Furthermore, physicians in private practice and generalists are more likely to prescribe a new treatment compared to those working in public settings and specialists, respectively.24,25

Diabetes care clinicians may experience additional external barriers to promoting device use in their patients such as limited time in clinic to work with their patients using devices and limited time to learn about new developments in diabetes technology. Furthermore, clinicians may also have different criteria for whom they consider to be a “good candidate” for a diabetes device. For example, a qualitative study following an insulin pump trial found that study staff had held assumptions about would be a successful pump user, and discovered through the trial that these assumptions could often be inaccurate.26 Therefore, the goal of this study was to better understand the different “personas” of clinicians in relation to their attitudes toward diabetes devices. The purpose of these personas is to provide insights into ways to further support clinicians in promoting device uptake among their patients who may benefit from these technologies.

Methods

Data were collected in the first half of 2016 from T1D diabetes providers through two recruitment sources: the T1D Exchange Clinic Network and dQ&A, a diabetes market research company that surveys panels of diabetes providers. More details about the sample, measures, and recruitment have been published previously.21 After excluding duplicate records (n = 14), noncompleters (n = 64), and providers who did not see patients with T1D (n = 7) we had a total sample of 209. K-means cluster analysis was used to segment T1D diabetes providers using six clustering variables relevant to their attitudes about CGM, resources for working with CGM data, and perceptions of patient barriers. These variables included (1) attitudes toward diabetes technology, (2) CGM-specific attitudes, (3) clinic time to work with patients using technology, (4) difficulty keeping up with diabetes technology advances, (5) cost barriers to using CGM, and (6) non-cost-related barriers to using CGM. We used these variables to group the sample and then evaluated these groups for validity using provider-specific and patient-specific variables (eg, practice setting, provider type, length of time in practice, demographics of patients seen). Simple Euclidean distance is used as the similarity measure for K-means cluster analysis.27,28

We examined 3- and 4-cluster solutions to create clinically meaningful, interpretable personas. Clustering variables were mean-centered prior to analyses for interpretability. Based on initial interpretation of each solution, we then examined validity evidence for the 3-cluster solution using ANOVA and chi-square tests and post hoc tests to assess differences between the personas based on the validating variables. ANOVA post hoc testing was done using the Gabriel procedure because personas contained different numbers of participants; the Games-Howell procedure was used for tests with unequal variances between groups. Significance was set at the P < .05 level. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 software (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL). Meaningful, significant differences between groups on validating variables were interpreted as evidence of meaningful differences between provider personas. The research team then created names to describe each clinician persona.

Measures

Clustering Variables

The following six variables were used to create the clinician personas.

Diabetes technology attitudes

This scale contained 7 items assessing clinicians’ attitudes toward diabetes technology (eg, “Diabetes technology has made my patients’ lives easier”; “I want my patients to have the latest and greatest technologies for diabetes”). Items are rated on a Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) and summed to create a total score (possible range = 7-35); higher scores indicate positive technology attitudes. Internal consistency for the current sample was .82.

CGM-specific attitudes

This was assessed with two items that were summed: “I believe use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) optimizes diabetes control” and “Most patients with type 1 diabetes can benefit from CGM.” These items were rated on the same 5-point Likert-type scale. Internal consistency for these two items in the current sample was .89.

Availability of time to work with patients using technology

Clinicians were asked to rate the following statement on the same 5-point Likert-type scale: “I have sufficient clinic time to review CGM data and adjust insulin doses during clinic visits for my patients with type 1 diabetes.”

Difficulty keeping up with advances in diabetes technology

Clinicians were also asked a single item about how difficult or easy they personally find it to keep up with diabetes treatment technology changes. Respondents answered this item using a slider bar from 0 to 100 with 0 = very easy and 100 = very difficult.

Clinician perceptions of their patients’ cost-related barriers to CGM use

Clinicians were asked three items to report whether or not they perceived insurance, cost of device, and cost of supplies to be barriers to their patients using CGM. Respondents could check “yes” or leave each item blank. Individual item scores (0 or 1) were summed to create a total score (range = 0-3). Internal consistency for these three items was .64.

Clinician perceptions of patients’ other barriers to CGM use

Clinicians were asked 16 items to report whether or not they perceived other non-cost-related issues to be barriers to their patients using CGM. Respondents could select as many barriers as they felt applied to their patients. Items on the list were developed through literature review, market research, and findings from our T1D adult survey.18 Items fell into several categories, such as not liking devices on their body, feeling nervous to rely on technology, or not wanting attention from others due to wearing devices. Individual item scores (0 or 1) were summed to create a total score (range = 0-16). Internal consistency for these items was .83.

Validating Variables

The variables used to test differences between the personas were characteristics of the provider, their practice, and their patient population.

Provider characteristics

We asked clinicians to report provider type, provider age, gender, race and ethnicity; practice setting (urban/suburban/rural); practice type (academic medical center, community hospital, large group practice, etc); and length of time in practice.

Practice and patient characteristics

These variables were self-reported and included: percentage of patients with T1D; pediatric, adult, or both; percentage of patients using insulin pumps and CGM; race and ethnicity of their patients; percentage of patients on public health insurance; and percentage of patients requiring an interpreter.

Mistrust in diabetes technology companies

We assessed clinician level of mistrust in diabetes technology companies with 5 items on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). These items were adapted from the validated Medical Mistrust Index29 using “diabetes technology companies” in the place of “health care organizations.” Sample items included “Diabetes technology companies don’t always keep your information totally private” and “Doctors/providers have sometimes been deceived or misled by diabetes technology companies.” Items were summed to create a total score (range = 0-20). Internal consistency for the current sample was .80.

Results

Participant characteristics are reported in Table 1. Diabetes care clinicians (N = 209) included endocrinologists (14.4%), certified diabetes educators (CDE; 60.3%), nurse practitioners (16.7%), registered dietitians (RDs; 24.4%), and others. The sample was predominately female (92.3%) and white (91.4%). Clinician practice settings were predominately urban (57.2%) and academic medical centers (46.9%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Full Sample and Differences by Clinician Persona.

| Clinician characteristics N (%) |

Full sample N = 209 |

Ready n = 42 |

Cautious n = 85 |

Not Yet Ready n = 82 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .02 | ||||

| <35 | 35 (16.7) | 12 (28.6) | 17 (20) | 6 (7.3) | |

| 36-45 | 50 (23.9) | 9 (21.4) | 23 (27.1) | 18 (22.0) | |

| 46-55 | 49 (23.4) | 9 (21.4) | 24 (28.2) | 16 (19.5) | |

| 56+ | 74 (35.4) | 12 (28.6) | 21 (24.7) | 41 (50) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Female gender | 193 (92.3) | 37 (88.1) | 76 (89.4) | 80 (97.6) | .07 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White or Caucasian | 191 (91.4) | 35 (83.3) | 81 (95.3) | 75 (91.5) | .08 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 16 (7.7) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (5.9) | 5 (6.1) | .20 |

| Hispanic | 8 (3.8) | 3 (7.3) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.8) | .40 |

| Black or African American | 5 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.1) | .02 |

| Native American | 4 (1.9) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | .32 |

| Professional status | |||||

| Endocrinologist (MD/MBBCh/DO) | 30 (14.4) | 10 (23.8) | 14 (16.5) | 7 (8.5) | .12 |

| Licensed practical nurse (LPN) | 2 (1) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | .42 |

| Registered nurse (RN) | 76 (36.4) | 11 (26.2) | 29 (34.1) | 36 (43.9) | .13 |

| Nurse practitioner (NP) | 35 (16.7) | 10 (23.8) | 14 (16.5) | 11 (13.4) | .34 |

| Certified diabetes educator (CDE) | 126 (60.3) | 16 (38.1) | 45 (52.9) | 65 (79.3) | <.001 |

| Registered dietitian (RD) | 51 (24.4) | 6 (14.3) | 17 (20) | 28 (34.1) | .02 |

| Other | 22 (10.5) | 5 (11.9) | 12 (14.1) | 5 (6.1) | .23 |

| Practice setting | .06 | ||||

| Urban | 119 (57.2) | 28 (66.7) | 54 (63.5) | 37 (45.7) | |

| Suburban | 63 (30.3) | 12 (28.6) | 22 (25.9) | 29 (35.8) | |

| Rural | 26 (12.5) | 2 (4.8) | 9 (10.6) | 15 (18.5) | |

| Practice type | .04 | ||||

| Academic medical center | 98 (46.9) | 24 (57.1) | 44 (51.8) | 30 (36.6) | |

| Community hospital | 40 (19.1) | 2 (4.8) | 16 (18.8) | 22 (26.8) | |

| Large group practice | 35 (16.7) | 10 (23.8) | 15 (17.6) | 10 (12.2) | |

| Small group practice | 18 (8.6) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (4.7) | 11 (13.4) | |

| Solo practice | 12 (5.7) | 1 (2.4) | 4 (4.7) | 7 (8.5) | |

| Other | 6 (2.9) | 2 (4.8) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.4) | |

P-values that were significant at the <.05 level are indicated in bold.

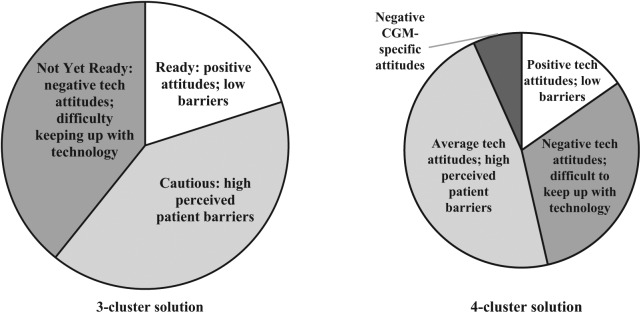

Selection of the 3-Cluster Solution

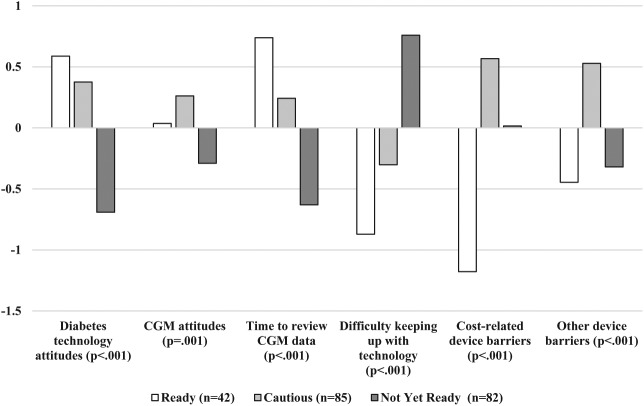

Figure 1 provides an overview of 3- and 4-cluster solutions. Both solutions had one group of clinicians (20%; 15% of the sample, respectively for 3- and 4-cluster solutions) with more positive attitudes toward technology, adequate time to keep up with technology and work with patients using CGM, and lower perceived patient barriers; a second group (41%; 47%) with high perceived patient barriers to using devices; and a third group (39%; 31%) with more negative technology attitudes, limited time to work with patients to review CGM data, and difficulty keeping up with technology advances. In the 4-cluster solution, a fourth small group (7%) was similar to the third in terms of having negative technology attitudes and difficulty keeping up with technology but stood out for having much more negative views toward CGM. Given the small size of this group and similarity to the third group, it was decided to proceed with the 3-cluster solution. The research team generated the following descriptive names in relation to clinician “readiness” to increase uptake of CGM among their patients: Ready, Cautious, and Not Yet Ready. Figure 2 shows differences in clustering variables across the three personas.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of the 3- and 4-cluster solutions.

Figure 2.

Differences between personas by mean-centered clustering variables.

Validation Analyses

Tables 1 and 2 contain results from ANOVA and chi-square tests to examine differences in provider, patient and practice characteristics between personas. We found significant differences between these groups with regards to their age, χ2(10, N = 208) = 21.61, P = .02; level of mistrust in diabetes technology companies, F(2, 205) = 3.83, P = .02; whether they primarily saw pediatric patients, adults, or both, χ2(4, N = 208) = 27.80, P < .001; percentage of black/African American patients seen, F(2, 206) = 3.45, P = .03; the proportion of patients they see with T1D, F(2, 205) = 3.29, P = .04; the proportion of their T1D patients currently using insulin pumps, F(2, 206) = 9.93, P < .001, and CGM, F(2, 206) = 11.31, P < .001. Groups also had significant differences in numbers of CDEs, χ2(2, N = 209) = 22.90, P < .001, and RDs, χ2(2, N = 209) = 7.44, P = .02, as well as type of practice (academic medical center, community hospital, large or small group practice), χ2(10, N = 209) = 19.17, P = .04.

Table 2.

Differences Between Clinician Personas by Provider, Patient, and Practice Characteristics.

| Ready (n = 42) |

Cautious (n = 85) |

Not Yet Ready (n = 82) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of total sample | 20.10 | 40.67 | 39.23 | |

| Provider characteristics | ||||

| Years in profession | 11.3 (9.86) | 13.34 (9.61) | 14.92 (8.33) | .13 |

| Mistrust in diabetes technology companies | 10.02 (2.32) | 11.11 (2.16) | 10.88 (1.91) | .02 |

| Provider type (pediatric/adult/both) | ||||

| Pediatric provider, n (%) | 23 (55%) | 26 (31%) | 11 (14%) | |

| Adult provider, n (%) | 8 (19%) | 40 (47%) | 51 (63%) | <.001 |

| Provider for peds and adults, n (%) | 11 (26%) | 19 (22%) | 19 (23%) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| % on public insurance | 43.34 (19.57) | 39.39 (21.74) | 43.24 (24.35) | .47 |

| % requiring interpreter | 7.88 (6.75) | 8.49 (11.38) | 10.49 (11.70) | .35 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| % black | 17.83 (10.53) | 20.06 (15.91) | 25.15 (18.89) | .03 |

| % white | 66.71 (13.97) | 63.9 (19.66) | 58.15 (23.82) | .06 |

| % Hispanic | 15.56 (9.90) | 16.31 (13.01) | 17.84 (16.01) | .64 |

| Practice characteristics | ||||

| % of diabetes patients with T1D | 67 (28.97) | 54 (33.62) | 33 (31) | <.001 |

| % T1D patients using pump | 58.14 (20.98) | 53.91 (25.14) | 39.35 (28.48) | <.001 |

| % T1D patients using CGM | 33.36 (23.16) | 30.32 (22.34) | 17.55 (17.91) | <.001 |

Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. P-values that were significant at the <.05 level are indicated in bold.

Clinician Personas

Ready clinicians (n = 42; 20.1% of the sample) had the most positive attitudes toward diabetes technology in general and the most time in clinic to review CGM data with their patients. These clinicians found it least difficult to stay current with updates in diabetes technology and perceived their patients to have the fewest barriers to using CGM. This group saw the largest proportion of patients with T1D (67%) and reported the highest rates of pump and CGM uptake among those patients (pump: 58%; CGM: 33%). These clinicians were more likely to be pediatric providers (55% were pediatric; 26% saw both pediatric and adult patients). This group contained a smaller proportion of CDEs and RDs than the Not Ready group (P = .02). They had a greater number of providers under 35 and fewer providers over 56 than the Not Ready group (P = .02).

Cautious clinicians (n = 85; 40.67%) had positive attitudes toward diabetes technology and CGM. They fell in between the Ready and Not Ready groups in terms of time in clinic to review CGM data and difficulty keeping up with technology advances. However, they perceived their patients to have the highest number of barriers—both cost and otherwise—to using CGM. This group saw a smaller proportion of T1D patients compared to the Ready group (54%) but reported similar rates of device uptake (pump: 54%; CGM: 30%) to the Ready group. However, the Cautious group had significantly greater levels of mistrust in diabetes technology companies compared to the Ready group (P = .02).

Not Yet Ready clinicians (n = 82; 39.23%) had the most negative attitudes toward diabetes technology in general and CGM specifically. They reported having the least amount of time in clinic to work with patients on reviewing CGM data. They reported that it was the most difficult for them to keep up with advances in diabetes technology. In terms of barriers they perceived their patients experienced for using CGM, they fell in between the other two groups. The Not Yet Ready group saw a larger proportion of black/African American patients (25.15%) compared to the Ready group (17.83%; P = .03). This group also saw a lower proportion (33%) of patients with T1D (versus T2D) compared to the other two groups and reported the lowest device uptake of the three personas (pump: 39%; CGM: 18%). The majority (63%) were adult providers, which was a higher proportion than the other two personas. This group had a higher proportion of CDEs and RDs compared to the Ready group. They were more likely to work in community hospital settings (26.8%) than the Ready group (4.8%; P = .04). Finally, half of the Not Yet Ready group were over 55 years of age, which was a larger proportion than the other two personas (P = .02).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to begin to understand groupings of diabetes care clinicians who share similarities regarding attitudes toward CGM, and time and resources for working with patients who are using CGM. Our analyses yielded three clinician personas to describe readiness to promote CGM uptake. We named these groups Ready, Cautious, and Not Yet Ready. These personas can inform research and clinical practice to support clinician readiness to promote newer diabetes treatment technologies, as different clinicians experience different barriers to increasing CGM uptake among their patients. For example, clinicians in the Cautious and Not Yet Ready groups endorsed having limited time to review CGM data with their patients, but the Not Yet Ready group also had more negative attitudes toward diabetes technology and reported seeing fewer patients using devices than clinicians in the Cautious group. Therefore, each group may benefit from different resources and support. Furthermore, the Not Yet Ready group reported working with fewer T1D patients than the other two groups which may limit their exposure to CGM, as individuals with T1D are currently the primary users of CGM. Thus, this group may require additional education and exposure to diabetes technology to shift attitudes about CGM compared with clinicians who work with a greater proportion of people with T1D.

The Cautious and Ready groups differed primarily by perceived barriers to CGM use in their patients; pump and CGM uptake rates were similar between these two groups and both groups had positive attitudes toward technology. The Cautious group perceived that their patients experience more barriers (cost-related and other barriers) than the other groups; given our study design, we are not able to confirm whether these patients would report the same barriers as their providers perceive. However, our previously published analyses indicated a mismatch between clinicians and people with T1D on certain barriers to device uptake, such as the need for education.21 Clinicians in the Cautious group may overestimate the barriers their patients experience; future research could survey matched clinicians and patients to assess level of alignment on perceived versus experienced barriers. If there is a misalignment, the Cautious group may benefit from brief training using a patient-centered, motivational interviewing approach30 to elicit concerns and priorities from their patients regarding CGM adoption. By aligning the clinician’s perception of barriers more closely with their patients, clinicians will be able to save time by focusing on the barriers that truly matter to people with T1D, likely increasing device uptake.

The Ready group reported the most positive attitudes toward diabetes technology, sufficient clinic time to review data, and fewer perceived patient barriers to CGM use compared to the other two groups. Still, this group reported that only an average of one-third of their patients were using CGM. It will also be important to understand what is already working for this group in terms of having time in clinic and the ability to keep up with new developments in diabetes technology to be able to employ some of these strategies for clinicians in the other groups. If CGM uptake increases over time, we need to better understand what kind of time commitment this will require from clinicians, and to prepare clinics with the resources they need to address any changes.

Other characteristics that differentiate the groups require further consideration. For example, provider age and proportion of patients treated who are black differed significantly between groups. Age tracks as expected in that younger health care providers are more likely to be in the Ready persona, which may also reflect the familiarity with diabetes devices such as CGM and comfort with technology in general. The difference on race may simply reflect the patient population in that more diversity is expected as the proportion of T1D patients treated goes down. However, it is possible it also reflects implicit biases that have been shown to be common in health care providers.31-34 Given the cross-sectional study design and reliance on provider report, these factors should be investigated in future research.

Limitations and additional future directions for research should be noted. First, the sample was primarily female and most clinicians were CDEs and either registered nurses or dietitians; endocrinologists made up less than a quarter of the sample. In addition, the survey was sent through a web-based platform to measure technology attitudes; thus, our results might also be skewed to include individuals who have more positive attitudes toward technology. To enhance generalizability, future studies should include a more diverse clinician sample with respect to gender and discipline and should consider additional recruitment approaches, such as clinic-based recruitment. Several of our survey items and measures were created or adapted specifically for this study and have not been validated previously, which may limit generalizability of our findings. Finally, we selected persona labels based on readiness to promote CGM use among their patients although we did not ask specifically about clinician “readiness.” It is possible that clinicians would self-report their readiness to promote CGM use among their patients differently than the items used in this analysis imply.

In summary, despite known benefits of CGM, uptake is low. Clinicians play a significant role in promoting CGM adoption among their patients; however, they report barriers to CGM uptake. The results of this study shed light on how to tailor behavioral and educational interventions for different groups of clinicians based on their attitudes toward the technology, the time and resources they have to learn about a new device and work with CGM data in clinic, and the barriers they perceive among their patients. These results, therefore, can provide a starting point for guiding the design and implementation of tailored interventions to better equip clinicians with the resources and tools to support their patients in adopting beneficial treatment technologies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CDE, certified diabetes educator; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; RD, registered dietitian; T1D, type 1 diabetes.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KKH receives research support from Dexcom, Inc for an investigator-initiated study and serves as a consultant to Bigfoot Biomedical, J&J Diabetes Institute, Lilly Innovation Center, and Insulet. The authors MLT, RNA, MSL, SJH, BIA, and DN declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the Leona M. & Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

ORCID iD: Molly L. Tanenbaum https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4222-4224

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4222-4224

References

- 1. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1464-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hermanides J, Phillip M, DeVries JH. Current application of continuous glucose monitoring in the treatment of diabetes pros and cons. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(suppl 2):s197-s201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in a clinical care environment evidence from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation continuous glucose monitoring (JDRF-CGM) trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):17-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Polonsky WH, Hessler D. What are the quality of life-related benefits and losses associated with real-time continuous glucose monitoring? A survey of current users. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15(4):295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Polonsky WH, Hessler D, Ruedy KJ, Beck RW. The impact of continuous glucose monitoring on markers of quality of life in adults with type 1 diabetes: further findings from the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(6):736-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pickup JC, Holloway MF, Samsi K. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes: a qualitative framework analysis of patient narratives. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):544-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaala SE, Lee JM, Hood KK, Mulvaney SA. Sharing and helping: predictors of adolescents’ willingness to share diabetes personal health information with peers. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Litchman ML, Allen NA, Colicchio VD, et al. A Qualitative analysis of real-time continuous glucose monitoring data sharing with care partners: to share or not to share? Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20(1):25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bailey T, Bode BW, Christiansen MP, Klaff LJ, Alva S. The performance and usability of a factory-calibrated flash glucose monitoring system. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(11):787-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pettus J, Edelman SV. Recommendations for using real-time continuous glucose monitoring (rtCGM) data for insulin adjustments in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(1):138-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ly TT, Buckingham BA. Technology and type 1 diabetes: closed-loop therapies. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2015;3(2):170-176. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hovorka R, Kumareswaran K, Harris J, et al. Overnight closed loop insulin delivery (artificial pancreas) in adults with type 1 diabetes: crossover randomised controlled studies. BMJ. 2011;342:d1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tauschmann M, Allen JM, Wilinska ME, et al. Day-and-night hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a free-living, randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(7):1168-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tauschmann M, Allen JM, Wilinska ME, et al. Home use of day-and-night hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery in suboptimally controlled adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a 3-week, free-living, randomized crossover trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):2019-2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Russell SJ. Progress of artificial pancreas devices toward clinical use: the first outpatient studies. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2015;22(2):106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wong JC, Foster NC, Maahs DM, et al. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring among participants in the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(10):2702-2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, et al. Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the US: updated data from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(6):971-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tanenbaum ML, Hanes SJ, Miller KM, et al. Diabetes device use in adults with type 1 diabetes: barriers to uptake and potential intervention targets. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(2):181-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. T1D Exchange.Why do some people with T1D stop using a pump and CGM? 2016. Available at: https://t1dexchange.org/pages/why-do-some-people-with-t1d-stop-using-a-pump-and-cgm/. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- 20. Barnard KD, Pinsker JE, Oliver N, et al. Future artificial pancreas technology for type 1 diabetes: What do users want? Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(5):311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanenbaum ML, Adams RN, Hanes SJ, et al. Optimal use of diabetes devices: clinician perspectives on barriers and adherence to device use. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(3):484-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peyrot M, Rubin RR. Physician perception and recommendation of insulin pens for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(8):2413-2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Factors associated with physician perceptions of and willingness to recommend inhaled insulin. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(2):285-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohlsson H, Chaix B, Merlo J. Therapeutic traditions, patient socioeconomic characteristics and physicians’ early new drug prescribing–a multilevel analysis of rosuvastatin prescription in south Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(2):141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tamblyn R, McLeod P, Hanley JA, Girard N, Hurley J. Physician and practice characteristics associated with the early utilization of new prescription drugs. Med Care. 2003:895-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lawton J, Kirkham J, Rankin D, et al. Who gains clinical benefit from using insulin pump therapy? A qualitative study of the perceptions and views of health professionals involved in the Relative Effectiveness of Pumps over MDI and Structured Education (REPOSE) trial. Diabet Med. 2016;33(2):243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. IBM. K-means cluster analysis. 2017. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/en/SSLVMB_24.0.0/spss/base/idh_quic.html.

- 28. Clatworthy J, Buick D, Hankins M, Weinman J, Horne R. The use and reporting of cluster analysis in health psychology: a review. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10(3):329-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, Williams KP. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(6):2093-2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Erickson SJ, Gerstle M, Feldstein SW. Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health care settings: a review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159(12):1173-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, Faulconer W, Hinton E, Sterling S. A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(8):895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sabin JA, Greenwald AG. The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):988-995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]