Abstract

Background

The Virtual Electrosurgical Skill Trainer (VEST) is a tool for training surgeons the safe operation of electrosurgery tools in both open and minimally invasive surgery. This training includes a dedicated team-training module that focuses on operating room (OR) fire prevention and response. The module was developed to allow trainees, practicing surgeons, anesthesiologist and nurses to interact with a virtual OR environment, which includes anesthesia apparatus, electrosurgical equipment, a virtual patient, and a fire extinguisher. Wearing a head mounted display, participants must correctly identify the ‘fire triangle’ elements and then successfully contain an OR fire. Within these virtual reality (VR) scenarios, trainees learn to react appropriately to the simulated emergency. A study targeted at establishing the face validity of the virtual OR fire simulator was undertaken at the 2015 Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) conference.

Methods

Forty-nine subjects with varying experience participated in this Institutional Review Board approved study. The subjects were asked to complete the OR fire training/prevention sequence in the VEST simulator. Subjects were then asked to answer a subjective preference questionnaire consisting of sixteen questions, focused on the usefulness and fidelity of the simulator.

Results

On a 5-point scale, 12 of 13 questions were rated at a mean of 3 or greater (92%). Five questions were rated above 4 (38%), particularly those focusing on the simulator effectiveness and its usefulness in OR fire safety training. 33 of the 49 participants (67%) chose the virtual OR fire trainer over the traditional training methods such as a textbook or an animal model.

Conclusions

Training for OR fire emergencies in fully immersive VR environments, such as the VEST trainer, may be the ideal training modality. The face validity of the OR fire training module of the VEST simulator was successfully established on many aspects of the simulation.

Keywords: FUSE, Electrosurgery, OR fire, Virtual reality, Simulator

Introduction

Electrosurgery is used to coagulate, dissect and ablate tissues [1]. Despite the widespread use of electrosurgery, it is well established that even experts lack knowledge in the proper and safe usage of electrosurgical devices [2]. Improper use of electrosurgery devices has resulted in injuries to both patients and operating room staff, OR fires and even death [3].

Operating room fires are uncommon but devastating events. According to the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI) between 550 and 650 operating room fires occur each year [5]. These numbers equal those of wrong-site surgery cases per year [6]. The Joint Commission issued a sentinel event alert on preventing surgical fires in 2009 [7]. Surgical fire prevention was also identified as 1 of the 11 priority safety topics by the Association of peri-Operative Registered Nurses (AORN) Presidential Commission on Patient Safety [8]. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration has created a fire prevention tasked force to promote operating room fire safety [9].

To address this knowledge gap, SAGES had established the Fundamental use of Surgical Energy (FUSE) program [4]. To complement this effort, the Virtual Electrosurgical Skill Trainer (VEST) is being developed to train surgeons in both the cognitive and motor skills required to safely operate electrosurgery tools in both open and minimally invasive procedures. VEST is envisioned to contain multiple modules, each one dealing with a specific aspect of electrosurgical safety.

The first VEST module (“Mod 0”), focusing on the monopolar surgical instruments and the associated tissue effects for various power settings and modes (cutting, coagulation, blend), has been developed and was successfully validated at the 2014 SAGES Learning Center [1]. Building on this success, we developed an immersive VR environment to teach skills in operating room (OR) fire prevention and response.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted at the Learning Center at the 2015 SAGES Conference. Any attendee at the conference was welcome to stop by and try the VEST Simulator station with the OR Fire module. Word of mouth was also used to increase awareness of the simulator. The SAGES attendees who participated ranged in experience from students to attending surgeons. A total of 49 subjects with varying surgical and FUSE training experience participated in this Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved study. The subjects were asked to complete the OR fire training/prevention sequence using the VEST simulator by correctly identifying the ‘fire triangle’ elements and then successfully containing an OR fire caused by an O2 enriched environment under the surgical drape. Following the completion of the training sequence, subjects were asked to answer a 5-point Likert scale subjective preference questionnaire consisting of thirteen questions, focused on the perceived usefulness and validity of the simulator (Table 1). The subjects were also able to identify the preferred method of training for OR fire scenarios, as well as identify any points of confusion and/or potential improvements to the simulator (Table 2).

Table 1:

Subjective preference of the VEST OR fire simulator (5-point Likert scale)

| # | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | I feel I have a better understanding of electrosurgical principles after using the VEST simulator (Likert scale 1 (don’t agree) −5 (agree)) |

| 2 | I feel learning electrosurgical principles with the VEST simulator is more effective than just textbooks alone (Likert scale 1 (don’t agree) −5 (agree)) |

| 3 | Using the VEST simulator to learn electrosurgical principles is more enjoyable than just using textbooks (Likert scale 1 (don’t agree) −5 (agree)) |

| 4 | If the VEST simulator was available to me in my skills lab, I would use it (Likert scale 1 (don’t agree) −5 (agree)) |

| 5 | I would recommend the VEST simulator to others who are interested in learning electrosurgical principles and practicing techniques (Likert scale 1 (don’t agree) −5 (agree)) |

| 6 | After using the VEST simulator, I will change my practices in the OR (Likert scale 1 (don’t agree) −5 (agree)) |

| 7 | Compared to actual surgery, tissue effects in the simulator are (Likert scale 1 (not realistic) −5 (very realistic)) |

| 8 | Compared to actual surgery, the instrument handling on the simulator is (Likert scale 1 (not realistic) −5 (very realistic)) |

| 9 | Please rate the degree of overall realism of the VEST simulation (how it looks AND feels), compared to the corresponding surgical task (Likert scale 1 (not realistic) −5 (very realistic)) |

| 10 | Please rate the quality of the force feedback (sensation of feeling the tools on the target and in the task space) in the VEST simulator compared to actual surgery (Likert scale 1 (not realistic) −5 (very realistic)) |

| 11 | Please rate the degree of usefulness of the force feedback (sensation of feeling the tools on the target and in the task space) in the VEST simulator in helping your performance (Likert scale 1 (not realistic) −5 (very realistic)) |

| 12 | Please rate the usefulness of the VEST simulator in learning hand-eye coordination skills, compared to an animal model (Likert scale 1 (not realistic) −5 (very realistic)) |

| 13 | Please rate the degree of overall usefulness of the VEST simulator in learning electrosurgical techniques and principles compared to an animal model (Likert scale 1 (not realistic) −5 (very realistic)) |

Table 2:

Subjective preference of the VEST OR fire simulator (general questions)

| # | Question |

|---|---|

| 14 | For electrosurgical skill training, which model do you prefer? (VEST simulator, animal model) |

| 15 | Did you encounter any confusion when using the VEST simulator? If yes, what was the confusion |

| 16 | Can you suggest how we might make the VEST simulator look or feel more realistic (e.g., perceptual cues, or additional features)? |

The OR fire training simulator provides OR fire training/prevention in the form of identification of the OR “fire triangle” elements and containment of an OR fire caused by O2 enrichment under the surgical drape. The actual training sequence consisted of four individual sub-scenarios:

[1]. Subject acclimatization

The subject dons the Oculus HMD, making sure the device is fitted properly and the subject is able to explore the virtual environment comfortably. The subject is then given the interaction device (left or right hand, depending on the preference), and instructed to visually locate the corresponding virtual model of the same tool in the virtual OR environment in order to establish a point of reference for the subsequent environment manipulation. The subject then identifies and selects the two objects in close proximity (the surgical drape and the electrosurgical pencil) using the selection sphere and then the two objects located at some distance from the user (the extinguisher and monitor) using the selection sphere. Once the subject indicates that he/she is comfortable with the object selection in the virtual environment the training sequence is advanced to the next step.

[2]. Fire triangle identification

The subject follows the prompts displayed in the virtual environment and identifies all objects that can be classified as “Fire Triangle” elements. The subject is first tasked with identifying all fuel sources, followed by all oxidizer sources, and, finally, all sources of ignition. A heads-up display is used to provide real-time feedback to the subject as he/she is progressing through the scenario. Once all the fire triangle elements have been identified the training sequence advances to the fire containment scenario.

[3]. Fire containment

Based on currently established protocol, if a fire does occur in the operating room, the OR personnel should immediately stop all airway gas flow and disconnect the patient from the breathing circuit, remove all burning and burned materials in or on the patient, and then extinguish the fire[6]. The simulator enables the subject to perform these steps in the following fashion:

The O2 gas pooling area of the surgical drape is highlighted and the subject is instructed to bring the electrosurgical pencil close enough to the ‘pooled’ areas of the drape for sparking to occur, activate the tool, and observe/react to the fire/explosion.

The subject is then able to select both the anesthesia workstation and the anesthesia mask. Upon selection, the anesthesia mask is removed from the patient’s face and is placed on the surgical room floor. Both objects need to be selected in order to terminate the gas flow.

The subject is then able to select the burning surgical drape in order to remove it from the patient. The drape is placed on the floor next to the surgical table and continues to burn.

The subject is then able to select the fire extinguisher off the operating room wall and extinguish the burning surgical drape. Upon selection of the fire extinguisher it appears in the subject’s hands, and she/he can then activate it as needed by pressing the interaction device button.

The fire is extinguished after approximately 5 seconds of fire extinguisher activation and the training scenario is complete, advancing to the training summary.

[4]. Training summary

The virtual OR environment is reset to the initial condition, and the subject is given a verbal summary of the training sequence, outlining the accomplished learning objectives and the corresponding training activities experienced by the subject. The simulator does have the capability to track the amount of errors but this functionality was not used at the SAGES Learning Center. The simulation will not continue until the user has done the scenario correctly, and therefore no one can “fail” the module.

The functionality of the VEST OR fire simulator is provided by two primary components-the hardware interface and the custom simulation software. Prior to the development of the first version of the OR fire training simulator, careful analysis of contemporary fire occurrence conditions and statistics, in addition to the currently recommended response sequence to an OR fire, was performed. In order for a fire to occur, three elements, commonly referred to as the “Fire Triangle”, must be present. These three elements are: (1) a source of heat or ignition (e.g., an Electrosurgical Unit); (2) a source of fuel (e.g., surgical drapes and/or surgical prep material); and (3) an oxidizer (most commonly O2 and/or nitrous oxide (N2O) gases). The ECRI published data claims that approximately 21% of surgical fires occur in the airway, 44% around the head, neck, face, or upper chest, and the remainder elsewhere [7], with about 70% of the occurrences taking place on the patient and just under 30% in the patient. In the majority of cases (70%), the ignition source is the electrosurgical equipment, however unconnected fiberoptic light cables were also listed as a likely source of fire. ERCI also advised providers to be particularly aware of the O2 enriched areas under the surgical drapes.

Hardware interface

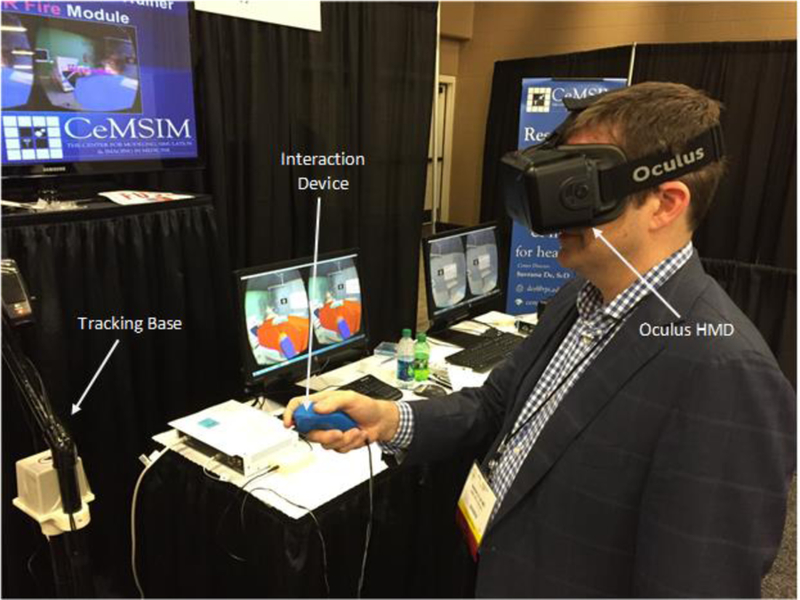

An effective and realistic multi-modal interface is an essential part of a successful surgical simulator. The OR fire training module of the VEST simulator utilizes a novel fully virtual interface, consisting of two primary components: an immersive 3D display and an interaction device (Fig. 1). The former is provided by the Oculus Rift stereoscopic helmet-mounted display (HMD) [16]. The Oculus Rift HMD offers precise tracking. By using a low persistence OLED display to drastically reduce motion blur and judder, the simulator sickness that was common with the previous-generation virtual reality helmets is virtually non-existent with the VEST module. The interaction with the virtual environment is provided via a custom-built 3D-printed controller, held by the user during the simulator’s operation. The controller incorporates a 6 degree-of-freedom positional tracker from Ascension Technology Corporation [17], as well as a push-button switch, allowing the user to ‘touch’ the virtual objects and interact with them as needed. A custom-built stand is used to place the wireless tracking base and the Oculus position-sensing camera at the locations optimal for maximizing the range of motion available to the user.

Figure 1:

OR fire training simulator interface

Simulation software

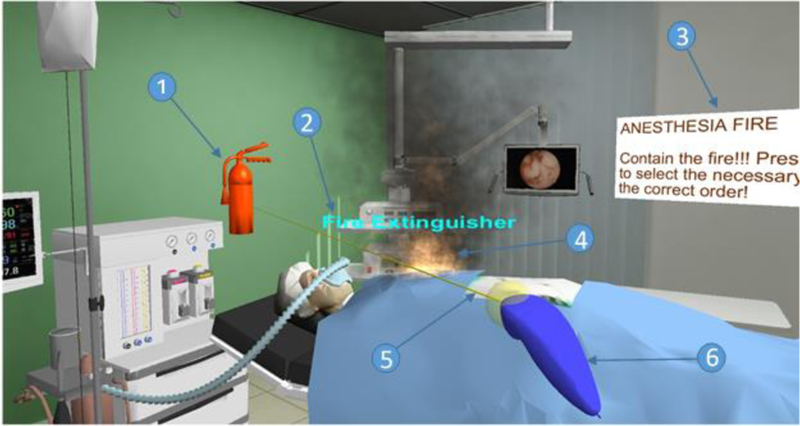

VEST OR fire simulator software functionality is provided by two main modules: graphics and simulation. These modules are built on top of the current version of a general purpose virtual reality framework – Software Framework for Multimodal Interactive Simulations (SoFMIS) [18]. VEST relies on a variety of three dimensional (3D) mesh models, obtained from the public domain, purchased, and generated in-house. The virtual OR fire training simulator needs to provide the participants with a highly realistic interactive version of a real-world operating room. Consequently, the essential components of the virtual OR fire simulator/trainer were identified and implemented. The items were a3D model of an operating room, 3D models of the fuel sources – (surgical drape and an anesthetic workstation.), the oxidizer source (anesthetic mask), and the ignition sources (an electrosurgical pencil and a fiberoptic light source cable), The simulated fire and smoke are based on an open-source particle engine software framework [19]. Particle systems are commonly used to model “fuzzy” objects, such as clouds, smoke, water, and fire, which have proved to be difficult to reproduce with conventional rendering techniques [20]. In a particle system, the simulated phenomenon is represented with a dynamic cloud of primitive particles that define its volume rather than boundary. During the visualization phase of the simulator’s execution, each “living” particle is replaced by a small image of a single puff of smoke or a small flame element. The combination of these individual small image fragments, dynamically appearing, moving, and disappearing within the virtual environment results in a highly realistic and visually appealing representation of fire and smoke (Fig. 2).

Figure 2:

Simulated OR fire, caused by a gas enrichment area under the surgical drape

Figure 2 depicts a typical state of the virtual environment as seen by the user: (1) currently selected object, (2) heads-up status text, (3) static instructions, (4) simulated flame and smoke, (5) selection ray used for reaching distant objects, and (6) virtual avatar of the physical selection device. The heads-up status text always remains in front of the user, regardless of where he/she is currently looking, and is used for critical real-time training scenario updates (e.g., name of the currently selected object, indication of correct/incorrect action, etc.). Selection of the objects in the virtual environment is based on a two-tiered collision detection between the model of the interaction device and the virtual OR object. Axis-oriented bounding boxes are first used to identify the potential collision candidates, followed by a mesh-to-mesh collision check.

Results & Discussion

Prevention of OR fires necessitates an awareness of the risk factors. If an OR fire does occur, coordination by the healthcare providers is imperative in order to minimize the collateral damage [6]. While skin is an effective barrier against the thermal energy released during a surgical fire, the corresponding release of a significant amount of humoral mediators can cause vasoconstriction and edema not only locally but also in distant organs, sometimes hours after the fire incident [10]. Therefore, all surgeons, anesthesiologists and nurses in the operating room should be thoroughly trained not only in fire prevention techniques, but also in rapid containment of any fires that do occur.

Despite the well recognized need for OR fire training, strict regulations on the use of open flame or smoke in most hands-on surgical skills labs limit their capability for this training. Simulation has been employed widely in medicine for team training and crisis training. Even if a learner does well with textbook knowledge, he/she might not react appropriately in an actual crisis when there is a lot of emotional stress involved. An OR fire is clearly a stressful, crisis type of event and therefore simulation should be key element of OR Fire education.

Real fire-safety training approaches, such as the Interior Live Fire System (ILFTS) [11], are commonly used for firefighter training, but are not available to train OR personnel due to aforementioned regulations. Similar restrictions exist for simulated smoke sources, such as dry ice and fog machines. Even when the physical simulation of an OR fire is permitted (e.g., by dropping dry ice into water and routing the resulting vapor to a specific site on the patient’s body), the realism of the resulting fire is quite low and does not impose sufficient physical and mental stress onto the participants [12]. Standalone frame simulators, such as the Attack Digital Fire System from BullEx,® also have these same limitations [13]. Furthermore, if the inclusion of catastrophic OR fire events (e.g., combustible gas explosions) is desired, comprehensive training for surgical fire prevention becomes near impossible.

Virtual reality (VR) offers a valuable alternative to physical OR fire training. VR is defined as the technology that enables the creation of computer-generated three-dimensional environments, which can then be interactively experienced and manipulated by the participants [14]. According to Stuart [15], a virtual environment (VE) is a human–computer interface capable of providing ‘‘interactive immersive multisensory 3-D synthetic environments.’’ The VE removes the traditional interface of keyboard, mouse and monitor. Instead, position sensors are used in such systems to track the user’s motions and to update the visual and auditory displays in real time, allowing the participants to interact with the computer-generated environment as if it were real. In VR the severity of an OR fire scenario and the complexity of the anticipated user response is only limited by the software and/or hardware configuration of the VR simulator and can be easily modified or expanded as needed.

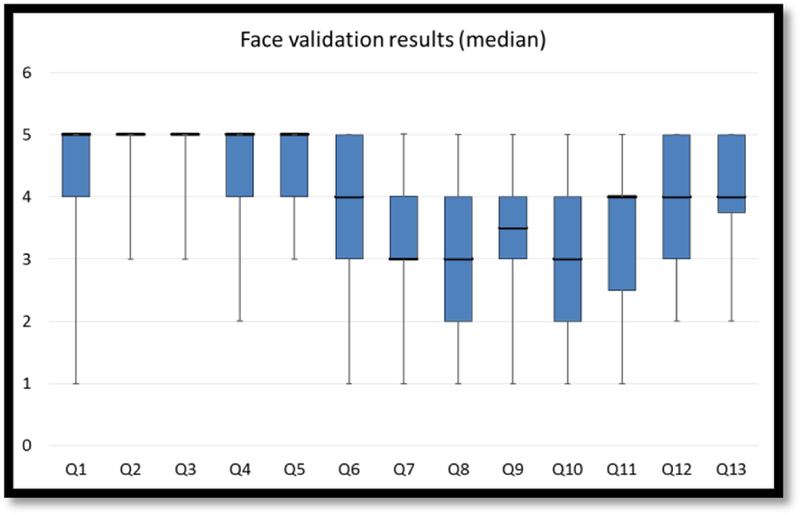

The results of the face validation study are provided in the Table 3 and Figure 3. Overall, 12 out of 13 questions were rated at the mean value of 3 or greater (92%). Five questions were rated above 4 (38%), particularly those focusing on simulator effectiveness and its usefulness in OR fire safety training. The highest score (mean – 4.84) was assigned to the level of satisfaction of using the VEST simulator to learn electrosurgical principles rather than just using textbooks, with the lowest score (mean – 2.95) associated with the quality of sensation of feeling the tools on the target and in the task space. 33 of the 49 participants chose the virtual OR fire trainer over the traditional training methods (67%).

Table 3:

Results of the face validation questionnaire (Subjective preference of the VEST simulator)

| # | Question | Response scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Mean | Std. Dev |

||

| 1 | Better understanding of electrosurgical principles | 5 | 4.33 | 0.98 |

| 2 | More effective compared to textbooks | 5 | 4.67 | 0.66 |

| 3 | More enjoyable compared to textbooks | 5 | 4.84 | 0.42 |

| 4 | Using VEST simulator in skills lab | 5 | 4.39 | 0.85 |

| 5 | VEST simulator recommendation | 5 | 4.55 | 0.67 |

| 6 | Changing OR practices | 4 | 3.82 | 1.20 |

| 7 | Tissue effects | 3 | 3.31 | 1.03 |

| 8 | Instrument handling | 3 | 3.02 | 1.01 |

| 9 | Overall realism | 3.5 | 3.52 | 0.76 |

| 10 | Quality of force feedback | 3 | 2.95 | 1.15 |

| 11 | Usefulness of force feedback | 4 | 3.33 | 1.16 |

| 12 | Usefulness in learning hand-eye coordination compared to an animal model | 4 | 3.82 | 1.01 |

| 13 | Usefulness in learning electrosurgical technique compared to an animal model | 4 | 3.94 | 0.94 |

Figure 3:

VEST OR fire trainer face validation results (median)

Subjects rated very highly the usefulness of the simulator in learning the OR fire prevention/training skills. The combination of the realistic visuals and the highly immersive interactive environment was deemed as a much better alternative to the traditional training methods. The results do show that some improvements are needed in the quality of the force feedback and the ease of interacting with the virtual OR environment. In their responses to question 15, 41% of participants had comments (and thus were possibly were confused by the simulator), while the remaining 29 (59%) seem to have had no confusion while using the simulator. In question 16, 23 (47%) of subjects offered suggestions on how to make the VEST simulator look and feel more realistic, while the remaining 26 (53%) had no additional comments. Fully virtual HMD-based surgical training modules are essentially nonexistent, and the associated fine details of user interface design are still being investigated.

This study is limited in that the aim is to provide design and face validity. The subjects were not offered an alternate method of OR Fire education for comparison. In addition the error rate in fire triangle identification was not tracked. In the future it would be helpful to be able to compare error rates to the subject’s self-reported prior electrosurgical education experience level.

Despite some current shortcomings, the study results indicate an extremely high level of importance associated with the virtual reality OR fire trainer by the participating physicians. A majority of the surveyed individuals were interested in using the trainer in their hands-on surgical skill labs and willing to recommend it to other physicians

Conclusion

Operating room fires are a well-recognized problem that necessitates proper training of all OR personnel. The training should encompass not only the fire prevention techniques, but also the rapid containment of any fires that do occur. However, OR fire training is complicated by the strict regulations currently in place with regards to open flame or smoke, enforced by most of the hands-on surgical skill labs. Training for OR fire emergencies in fully immersive virtual reality environments may be the ideal training modality. The VEST OR fire trainer was developed for this task and validated by the experts in the surgical community. Results of the validation study indicate a high level of importance associated with the virtual reality OR fire training. Further refinements based on the feedback are currently taking place, including an expanded set of didactic materials within the trainer and improved visuals. We are also planning to establish metrics capable of providing an objective evaluation of a subject’s performance after the training session. Ultimately, a series of validation studies aimed at ensuring that skills learned in the virtual environment are transferable to the real operating room environment will be conducted. Future technical advancements will allow multiple users (surgeon, anesthesiologist and nurse) to be immersed concurrently and interacting together as avatars.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank the FUSE VEST advisory committee, particularly Dr. Malcolm Munro, for the valuable feedback used to guide this research. The authors also grateful acknowledge the assistance of Sean Radigan (CeMSIM, RPI) for the technical support during the development of this simulator, and Becca Kennedy (CeMSIM, RPI) for recording the verbal summary of the training sequence.

Funding information: This project was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants NIH/NIBIB 2R01EB005807, 5R01EB010037, 1R01EB009362, 1R01EB014305

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Daniel B. Jones is the chair of the SAGES FUSE committee and consultant to Allurion and Intuitive Surgical. Dr. Steven Schwaitzberg has served on advisory panels and has received an honorarium from Stryker and Olympus. He has served on advisory panels for Neatstitch and Surgicquest, Arch Therapeutics Acuity Bio and Human Extensions. He has also received a grant from Ethicon. Dr. Suvranu, Denis Dorozhkin, Stephanie B. Jones, Caroline Cao, Jaisa Olasky, Marcos Molina, Steven Henriques, Jeff Flinn and Jinling Wang have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

References

- 1.Sankaranarayanan G, Li B, Miller A, Wakily H, Jones SB, Schwaitzberg S, Jones DB, De S, Olasky J (2015) Face validation of the Virtual Electrosurgery Skill Trainer (VEST(©)). Surg Endosc doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4267-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Feldman LS, Fuchshuber P, Jones DB, Mischna J, Schwaitzberg SD (2012) Surgeons don’t know what they don’t know about the safe use of energy in surgery. Surg Endosc 26:2735–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2263-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willson PD, McAnena OJ, Peters EE (1994) A fatal complication of diathermy in laparoscopic surgery. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 3:19–20. doi: 10.3109/13645709409152989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madani A, Jones DB, Fuchshuber P, Robinson TN, Feldman LS (2014) Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy™ (FUSE): a curriculum on surgical energy-based devices. Surg Endosc 28:2509–12. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3623-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ECRI (2009) 2010 top 10 technology hazards. Health Devices 38: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FUSE FUSE Manual. http://www.fuseprogram.org/. Accessed 29 Apr 2015.

- 7.Institute E (2009) New clinical guide to surgical fire prevention. Patients can catch fire--here’s how to keep them safer. Health Devices 38:314–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barfield Furness T.A. III W (2003) Virtual environments and advanced interface design. AORN J doi: 10.1016/S0001-2092(06)60673-X [DOI]

- 9.FDA Preventing Surgical Fires. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/SafeUseInitiative/PreventingSurgicalFires/default.htm. Accessed 2 Aug 2015.

- 10.Hart SR, Yajnik A, Ashford J, Springer R, Harvey S (2011) Operating room fire safety. Ochsner J 11:37–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DraegerSafetyInc Interior Live Fire Training System (ILFTS). http://www.draeger.com/sites/enus_us/Pages/Fire-Services/Interior-Live-Fire-Training-System-(ILFTS).aspx. Accessed 20 Jul 2015.

- 12.Corvetto MA, Hobbs GW, Taekman JM (2011) Fire in the operating room. Simul Healthc 6:356–9. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31820dff18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.BullEx Attack Digital Fire System. http://bullex.com/product/attack/. Accessed 20 Jul 2015.

- 14.Barfield Furness T.A. III W (1995) Virtual Environments and Advanced Interface Design Oxford University Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuart R (2001) The Design of Virtual Environments Barricade Books, Ft; Lee, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oculus VR Oculus Rift Development Kit 2. https://www.oculus.com/dk2/. Accessed 29 Apr 2015.

- 17.Corp. AT Ascension TrakSTAR2. http://www.ascension-tech.com/products/trakstar-drivebay/. Accessed 29 Apr 2015.

- 18.Halic T, Venkata SA, Sankaranarayanan G, Lu Z, Ahn W, De S A software framework for multimodal interactive simulations (SoFMIS). Stud Health Technol Inform 163:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SourceForge SPARK 1.5.5. http://sourceforge.net/projects/sparkengine/. Accessed 20 Jul 2015.

- 20.Reeves WT (1983) Particle Systems---a Technique for Modeling a Class of Fuzzy Objects. ACM Trans Graph 2:91–108. doi: 10.1145/357318.357320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]