Sir,

Pregnant women are susceptible to various physiological and pathological cutaneous changes.[1] These conditions are generally benign, but can cause substantial anxiety in affected patients. The profound hormonal, vascular, metabolic, and immunological changes occurring during pregnancy can attribute to all these dermatoses.[2]

Though there are multiple reports on this subject across the nation, we undertook this study because of the scarcity of the same from Northeast part of India, which has unique characteristics ethnically and geographically.

After obtaining ethical committee approval, this hospital-based cross-sectional study was carried out in the Departments of Dermatology and Gynecology at a tertiary center in Northeast India for 18 months duration from November 2012 to April 2014. Pregnant women above 18 years of age and above 12 weeks of gestation with skin changes were included in the study, after obtaining the consent. Patients not fulfilling the inclusion criteria, presenting with preexisting skin lesions, infections including sexually transmitted diseases and infestations were all excluded. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (version 20.0 for Windows, Chicago, IL, USA).

A total of 300 patients with complaints regarding skin and mucous membrane were included in the study. Maximum number of patients in the study belonged to 26–30 years (46%), followed by 20–25 years (33%) and 31–35 years (20%) [Table 1]. Primigravida patients constituted 51.6% of the sample. Maximum patients were in third trimester (67%).

Table 1.

Clinico-epidemiological profile of the patients

Pigmentary changes were seen in 67.3% patients, more commonly in multigravidas [Figures 1 and 2]. Linea nigra was seen in 93.9% of multigravidas, while only 55.5% of primigravidas were affected by the same [Table 2]. The second most common pigmentary change was pigmentation of the areola and nipple, which was seen in 77.5% of multigravidas as compared to 52.6% among primigravidas. Melasma was also more common in multigravidas (35.8%), while in primigravidas it constituted only 25.8%. But the association between the pigmentary changes in relation with the parity was statistically insignificant (P = 0.084). Pigmentary disorders were more common in the second trimester (86.6%) followed by 57.7% in the third trimester. Again, the association was not significant (P-value = 0.084).

Figure 1.

Diffuse, hyperpigmented patches over central face and malar region suggestive of melasma

Figure 2.

Linea nigra with whitish striae over abdomen

Table 2.

Distribution of pigmentary disorders and connective tissue changes with parity and duration of pregnancy

Connective tissue changes were seen in 72.6% of the pregnant women [Figure 3]. Abdominal striae were the most common type with more prevalence among multigravidas (81.4%) compared to primigravidas (61.9%) [Table 3]. Striae on the breast were observed only in 2.8% of multigravidas, while no primigravida was affected. However, these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.075). Connective tissue changes were seen more commonly among patients in second trimester (96.9%) than those in third trimester (60.6%). It was again statistically insignificant (P = 0.075).

Figure 3.

Multiple linear erythematous striae with a few excoriated plaques over abdomen

Table 3.

Distribution of other physiological changes with parity and duration of pregnancy

Other physiological changes were seen in 12.66% of pregnant women. This was also more common among multigravidas. Most common change was pedal edema seen in 12.4% of multigravidas and 7.1% of primigravidas. Hair changes including chronic telogen effluvium were seen in 2.8% of multigravidas and 1.9% of primigravidas. Palmar erythema was seen in 0.7% and 0.6% of multigravidas and primigravidas, respectively. These physiological changes were more common among patients in second trimester (15.1%) than those in third trimester (11.4%). However, there was no statistically significant difference with parity or duration of trimester (P = 0.925 for both).

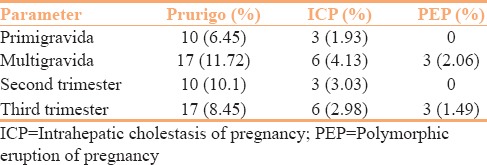

Pregnancy-specific dermatoses were seen among 13% of patients [Figure 4]. Among them, atopic eruption of pregnancy (AEP) was the commonest constituting 9%, followed by intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) (3%) and polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP) (1%) [Table 4]. No case of pemphigoid gestationis was reported during the study period. AEP was seen more in multigravidas comprising 11.7% compared to 6.5% among primigravidas. ICP was again more common in multigravidas constituting 4.1% compared to 1.9% in primigravidas. PEP was seen only in multigravidas (2.0%). The difference was not significant (P = 0.435). Specific dermatoses, except PEP, were marginally more prevalent among patients in second trimester (13.1%) than those in third trimester (12.9%). Again, no significance was found (P = 0.435).

Figure 4.

Atopic eruption of pregnancy on bilateral legs

Table 4.

Distribution of specific dermatoses with parity and duration of pregnancy

Our observation shares a similar pattern of pregnancy-associated dermatoses with those of earlier studies from other regions of India, excluding the effect of ethnical and geographical differences.[3,4,5,6,7] In the present study, normal physiological cutaneous changes were the most common changes, while specific dermatoses of pregnancy were rare. A detailed history and physical examination are important for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatoses of pregnancy that will direct the most appropriate laboratory evaluation and careful management in an effort to minimize maternal and fetal morbidity.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kar S, Krishnan A, Shivkumar PV. Pregnancy and skin. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:268–75. doi: 10.1007/s13224-012-0179-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rathore SP, Gupta S, Gupta V. Pattern and prevalence of physiological cutaneous changes in pregnancy: A study of 2000 antenatal women. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:402. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.79741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumari R, Jaisankar TJ, Thappa DM. A clinical study of skin changes in pregnancy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:141. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.31910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan I, Bashir S, Taing S. A clinical study of the skin changes in pregnancy in Kashmir Valley of North India: A hospital based study. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:28–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.147782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary R, Mahakal N, Chauhan A, Modi K. Dermatological disorders in pregnancy: A cross sectional study. Int J Sci Stud. 2015;3:118–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Indradevi R, Oudeacoumar P, Besra L, Anitha V. Pattern of specific dermatoses of pregnancy: A hospital based study. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2015;4:1817–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panicker VV, Riyaz N, Balachandran PK. A clinical study of cutaneous changes in pregnancy. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2017;7:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]