Abstract

In the early and mid-nineteenth century Europe, ringworm of the scalp was a vexing problem. It affected children in such numbers that the famous Hôpital Saint-Louis of Paris had a separate Tinea School. Before advent of radiation method of epilation, painful method of peeling was the mainstay of management. A family bearing title Mahon with no conventional medical training and qualification developed a secret method of epilation which was far superior to the existing method of treatment. Two brothers of this family, whose identity is obscure in the history of dermatology, were given the charge of treatment of such cases in various hospitals of France. Though they were not physician per se, their observations surprise us even today. Mahon the junior wrote a book on ringworm which is the first ever monograph on the subject. They also described favus of the nail and named ringworm of the scalp.

Keywords: Gray patch ringworm, history of ringworm, Mahon, Mahon brothers, ringworm, tinea

Introduction

It was 27th November, 1801. The l’Hôpital Saint-Louis of Paris with its about 1100 beds including 300 for its Tinea School was dedicated to dermatology with Jean Louis Alibert as the chief. It soon became the fountainhead of modern dermatology enriched with contributions from great masters like Beitt, Cazenave, Devergie, Bazin, Darier, and many others. But when an answer to the most vexing problem of dermatology of that era, scalp ringworm, comes from a non-physician family, especially from two brothers (also laymen), it demands discussion. This short article is about the Mahon brothers, whose contributions are landmarks in the history of dermatology.

Tinea in the Early Days

Though Celsus (c. 25 BC–c. 50 AD) gave the earliest description of kerion, confusion existed till the discovery of Microsporum auodinii as the cause of “gray patch” ringworm of the scalp in 1843.[1] The controversy hovered from favus to porrigo, from teignes to hèrpes circiné, and so on. The ailment classically affected children and the treatment was to confine them in hospital till adolescence when it resolved spontaneously or to epilate with an agonizing method of removing the scalp hair with a leather disc called calotte that were painted with pitch and applied on the scalp to epilate almost all hairs.[2]

Mahons and their Treatment

In this era of peculiar, painful, pitiable treatment, Mahon brothers, both senior and junior, members of a family engaged with epilation with some secret formula, were appointed “officially” not only at Saint-Louis Hospital but also at Lyons, Ruene, Dieppe, and so on. Their method was far better in efficacy and acceptability. Each of them was paid 1000 Francs as stipend along with 6 Francs per capita for every child cured. They used some powder and salve probably made of sulfur and sodium carbonate.[3] Mahon the junior discussed all prevailing treatments of scalp ring worm in his treatise but never divulged their own formulae. Even we do not know their full names.

Mahon's Contribution in Dermatology

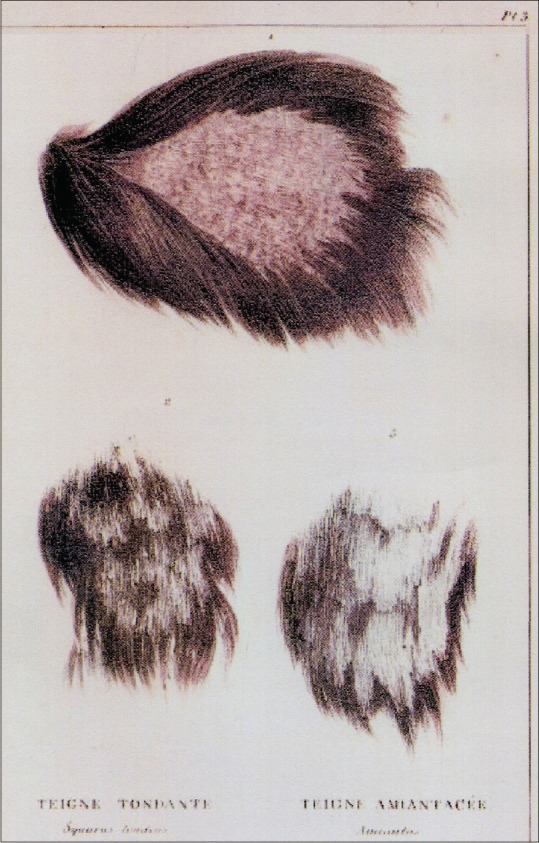

Indeed Mahons were no physicians per se, but their greatest contribution in dermatology was the first ever treatise on ringworm: Recherches sur le siége et la nature des teignes (Investigations on the site and nature of ringworm) in 1829 by the younger Mahon [Figure 1]. It contained 10 pages of preface, 30 pages of introduction, 373 pages of texts, and 5 colored plates [Figure 2]. He divided the book into 12 sections: Teigne faveuse, Teigne tondante, Teigne Amiantacée, Teigne furfuracée, Teigne muqueuse, Teigne granulée, Crasse laiteuse, Crasse membraneuse, Différences essentials qui existent entre les diverses teignes, Influence respective de Chaque teigne sur les phénmènes généraus qui les accompagnent, De la classification des affections qui été confondues sous le nom de teigne, and Des pricipaux traitemenes.[4] Mahon the senior recognized the scalp ringworm and named it Teigne tondante and also described favus of nails.

Figure 1.

Title page of Recherches sur le siége et la nature des teignes (1829) (Available from: https://wellcomelibrary.org/. Work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 1.0 https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/)

Figure 2.

Colored plate showing various affections of the scalp ringworm (Source: Mahon Jeune. Recherches sur le siége et la nature des teignes (1829). (Available from: https://wellcomelibrary.org/. Work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 1.0 https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/)

Epilogue

Since the early days sulfur remained the mainstay of treatment till the development of griseofulvin by Oxford in 1939 and the first azole, benzimidzole, by Wooley in 1944, though some other topical agents such as Whitfield ointment was in use since 1920.[5,6] In the nineteenth century and early part of the twentieth century, many other substances such as carbolic glycerine, Coaster paste, Goa powder or chrysophanic acid, and perchloride of mercury were used empirically with an intention to create a blister or irritation leading to scab formation and subsequent removal of the scab with an aim to get rid of lesions. Epilation of hairs in case of scalp ring worm was the mainstay of treatment either done physically or with depilatory agents. Methods were quite painful and horrible.[7] After 1896, the radiation therapy took the central role, but with a lot of hazards. The whole scenario changed and a new era of antifungal therapy began with the introduction of oral griseofulvin and topical chlorimidazole in 1958. The risk of radiation-associated complications could be averted. Thereafter, one after another oral and topical agents such as miconazole (1969), clotrimazole (1969), econazole (1974), naftifine (1974), ketoconazole (1981), fluconazole (1990), itraconazole (1992), echinocandins (2002), and various newer azoles such as voriconazole (2002) and posaconazole (2006) evolved to strengthen the armamentarium at present.[5,8] The situation was altogether different at the time when Mahon brothers were treating ringworms. The etiology and management of ringworms were yet to find a real scientific avenue. At times treatment was more painful than the disease itself.

It is sad to note that we hardly come across any major literature on the Mahon brothers who managed scalp ringworm at a time when nobody even knew its cause, and offered treatment that was far more acceptable. Not only treatment but also they offered the very first monograph on ringworm and a name to the scalp ringworm about 200 years ago. Certainly, their contribution demands place in the history of dermatology.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Potter BS. Bibliographic landmarks in the history of dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:919–32. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthel T. Early nineteenth century dermatology and brothers Mahon. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1934;10:706–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crissey JT, Parish LC. Historic aspect of nail diseases. In: Scher RK, Daniel CR III, editors. Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005. pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeune M. Recherches sur le siége et la nature des teignes. Paris: J B Baillère; 1829. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anaissie J, McGinnis MR, Pfaller MA. Clinical Mycology. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2009. pp. 161–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitfield A. Whitfield's ointment. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1920;1:684. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith A. Ringworm: Its diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia: Presley Blakiston; 1881. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryder NS, Mieth H. Allylamine antifungal drugs. Curr Topics Med Mycol. 1992;4:158–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2762-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]