Abstract

Background:

Childhood leprosy is an important marker of the status of the ongoing leprosy control programme, as it is an indicator of active disease transmission in the community. Despite achievement of elimination status of leprosy in 2005, the reported prevalence of childhood cases continue to be high.

Method:

A retrospective analysis of 11 year records of leprosy patients aged less than 15 years in a tertiary care hospital of central Delhi was carried out from 2005-2015. Data were analysed using SPSS 22.0 system.

Result:

A total of 113 (7.6%) cases of childhood leprosy were reported during the 11 year period from 2005-2015. Multibacillary cases constituted a total of 57 (50.4%), while paucibacillary constituted 56 (49.6%) cases. The M:F ratio noted was 2.5:1. Signs of reaction were found in 15% cases, while deformity was noted in 24.7% cases.

Conclusion:

The rate of childhood leprosy continues to be high. Lack of proper access to health facilities, ignorance among the general population, high susceptibility due to immature immune system etc make this population highly vulnerable.

Limitations:

Limited data of 11 years from an urban center were analyzed.

KEY WORDS: Childhood leprosy, hospital-based data, postelimination era, retrospective study

Introduction

India achieved elimination status for leprosy in 2005;[1] however, the reported prevalence continues to be high in some of the states and union territories. An important marker of the operational efficacy of the ongoing leprosy control program is the proportion of childhood leprosy cases. It reflects the active case transmission in the community. Many factors such as lack of awareness among the general population, difficulties in access to the health-care system, and lack of well-defined clinical signs in children make this section of population highly vulnerable. The present study was undertaken to study the clinicoepidemiological features of childhood leprosy cases in a hospital setup.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of all leprosy cases aged <15 years during the 11-year period (January 2005 to December 2015) attending the leprosy clinic at Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi, was carried out. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained before data were handled and no personal identifying information was included. The hospital catered to a large population of central Delhi as well as immigrant population from the neighboring states. The case detection was passive; no active search was carried out. Detailed history and examination findings recorded were analyzed. The age at onset, domicile, history of contact with a leprosy case, gender, etc., were noted. Detailed note of the examination findings included number of skin lesions, peripheral nerve thickening, signs suggestive of types 1 and 2 reactions, and presence of neuritis. Type 1 reaction was diagnosed if the patient developed redness, swelling and tenderness of the preexisting lesions, edema of hands and feet, face, or tenderness of one or more nerves, with or without nerve function impairment. Type 2 reaction was diagnosed in patients presenting with multiple small tender evanescent nodules and plaques, with or without constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, lymphadenitis, and myalgia.[2,3] Slit skin smear examination was done in all cases; histopathology was done wherever deemed necessary. Cases were classified according to the Ridley–Jopling classification.[4] The WHO classification was used for grading of the disability.[5]

Results

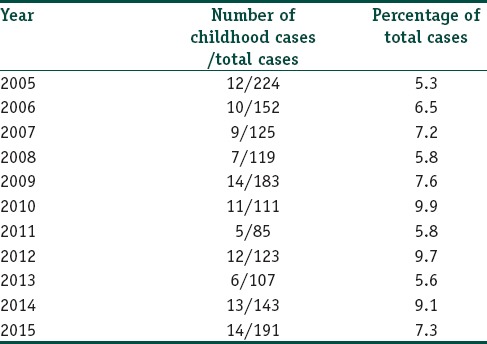

In the data analyzed from 2005 to 2015, 113 cases of childhood leprosy were recorded out of the total 1487 (7.6%) cases. The year-wise distribution of cases is shown in Table 1. Multibacillary cases constituted a total of 57 (50.4%) cases, while paucibacillary constituted 56 (49.6%) cases.

Table 1.

Year-wise distribution of the cases of childhood leprosy

Demographic profile

Majority of the cases (86, 76.1%) belonged to 11–15 years of age, followed by 25 (22.1%) in 6–10 years and 2 (1.8%) in 1–5 years. The preponderance of cases in the older age group could be accounted for by the long incubation period of the disease. Males outnumbered females in the present study, a total of 81 (71.7%) were male while 32 (28.3%) belonged to female gender (M:F ratio being 2.5:1).

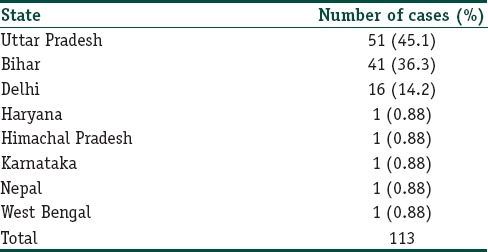

The majority of the cases were immigrant population from neighboring states. Most of the cases belonged to Uttar Pradesh (51, 45.1%), followed by Bihar (41, 36.3%). Patients belonging to Delhi were 16 (14.2%), while a minority of cases (1, 0.88%) belonged to Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Nepal, and West Bengal [Table 2].

Table 2.

The domicile of the cases

Clinical spectrum

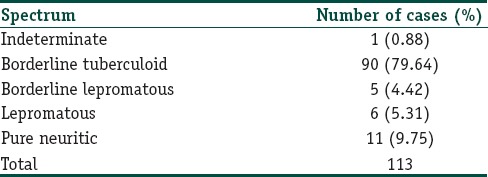

History of contact was elicitable in 4 (3.5%) cases. Only household contacts were included in the study. According to the Ridley–Jopling classification, majority of the cases (90, 79.64%) belonged to the borderline tuberculoid spectrum, followed by lepromatous spectrum (6, 5.31%). Among the total cases, 11 (9.75%) presented with only nerve involvement, while only 1 (0.88%) case of indeterminate leprosy was noted [Table 3].

Table 3.

Spectrum of the disease in the study

Five or less skin lesions were noted in 80 (70.8%) cases, while 33 (29.2%) reported >5 skin lesions. Single lesion was noted in 46 (40.7%) cases. The distribution of lesions in decreasing order of involvement included upper extremities, face, lower extremities followed by covered sites such as back and buttocks. A total of 67 (59.3%) cases presented with multiple nerve involvement, ulnar nerve being the most common followed by common peroneal.

Smear positivity and histopathology

Slit skin smear positivity was found among 8 (7.1%) cases, while the rest 105 (92.9%) did not reveal acid-fast bacilli on slit skin smear examination. Among the positive cases, 2 belonged to borderline lepromatous spectrum, while 6 belonged to the lepromatous leprosy spectrum.

Histopathology from the cases with skin lesions revealed consistent characteristics in 51 (45.1%) with the clinical diagnosis, while 16 (15.6%) revealed nonspecific findings [Table 4]. Histopathological features used for characterization included the presence or absence of granuloma, type and distribution of infiltrate, grenz zone. BT Hansen was the most common histological diagnosis. Biopsy was done in all cases, except for those who refused the procedure.

Table 4.

Results of the histopathological findings among the cases with skin lesions

Reaction and deformity

A total of 17 (15%) cases presented with signs of reaction. Among these, 14 had signs of type 1 reaction, while 3 cases were found to have type 2 reaction. Two cases reported signs of neuritis.

Disability was noted in 28 (24.8%) cases, majority of the cases (21, 18.6%) had Grade 2 disability, while 7 (6.2%) were found to have Grade 1 disability. Most of the cases presenting with disability belonged to multibacillary spectrum (71.4% in both Grades 1 and 2 disability). Among the total children suffering from disability, 18 (64.3%) had hand deformities, while the rest (35.7%) reported deformities of the feet. None of the cases were found to have ocular deformities.

Treatment

All cases with slit skin smear positivity, more than five skin lesions and more than one peripheral nerve involvement were classified as MB and received 12 months treatment, while the rest were classified as PB and underwent treatment for 6 months. Among the total patients receiving paucibacillary treatment, 45 (80.3%) completed treatment, while among the multibacillary cases, 47 (82.4%) completed treatment. About 18.6% cases were defaulter. A history of previous treatment was elicitable in 12 (10.6%) cases.

Reactions were treated according to the severity. Mild episodes with only cutaneous involvement were treated with only anti-inflammatory agents, while those complicated with systemic involvement received course of systemic corticosteroids. Patients with neuritis were given supportive measures such as slings along with corticosteroids. Deformities were managed with intensive physiotherapy and corrective surgeries.

Discussion

According to the progress report by NLEP 2015,[6] a total of 125,785 new leprosy cases were detected during the year 2014–2015, making the annual case detection rate 9.73 per 100,000 population. The proportion of childhood cases reported was 9.04%. The child disability rate was 0.019/100,000 population. The proportion of childhood cases is an important indicator of the success of the disease control program. It is governed by many factors such as the thoroughness of case detection, BCG vaccination, and stage of the control program. At the beginning of the control program, the rate may be lower due to a greater burden of adult cases and tends to stabilize later. As the duration increases, the rate becomes lesser.

The percentage of childhood leprosy in Delhi during the year 2014–2015 was 5.22%. The percentage of MB cases among these was 3.42%, while PB was 1.80%. The child disability case rate noted in Delhi was 0.03/100,000 populations.

In the present study, childhood cases constituted 7.5% of the total leprosy cases registered from 2005 to 2015. This finding in our study was similar to a study conducted by Grover et al.[7] from Delhi; they reported the childhood leprosy cases to constitute 7.06% of the total cases. Other studies had reported childhood leprosy rates to be 4.5%[8] and 9.6%.[9] The difference in the prevalence noted by different studies might be due to the difference in the cutoff age used in these studies along with other factors such as differences in case finding methods. Similar to the current study, other studies had also reported majority of the cases belonging to the higher age group (5–15 years).[10,11] The higher prevalence of cases in the older age group could be accounted for by long incubation period of the disease and failure to report in early stages. A high M:F ratio (2.5:1) was noted in our study. This finding was consistent with previous studies and could be attributed to neglect of girl child in the Indian setup.

A history of contact was elicitable in 3.5% of the cases in the present study, although the multibacillary/paucibacillary status of the contacts was not available from the records. The risk of transmission of leprosy was four times higher in case of neighborhood contact, while risk increased to nine times in case of intrafamilial contact.[12] Close contact with leprosy cases at home was an important source of infection, especially in children who had a weak immune response. This underlined the importance of screening of family members in a case of leprosy. Most of the patients belonged to Borderline Tuberculoid spectrum; this finding was consistent with other similar studies.[7,13] Single lesion was recorded in 45% cases in our study. Previous studies had reported mixed results regarding the number of lesions. While some studies reported single lesion to be more common,[14,15] others reported higher rate of multiple lesions.[8,16] Dogra et al.[2] reported multiple nerve thickening in 56.3% of cases in their study, which was similar to the figure cited in the present study (59.2%). The presence of multiple thickened nerves was a risk factor for the development of deformities and reactions. Smear positivity was noted among 7% of the cases. Previous studies documented rate of smear positivity to be <10% in cases of childhood leprosy.[17,18]

Multibacillary cases outnumbered the paucibacillary cases by a small margin. Many studies reported paucibacillary cases to predominate in case of children.[1,19] However, finding similar to the current study had also been documented in a study published from Delhi in 2011.[9] The probable explanation cited by the authors included difference in the classification system used in the different studies.

The histopathological concordance was seen in 50% cases in the present study. Sehgal et al.[6] reported a rate of 52%, while Kumar et al.[13] reported concordance in 60.6% cases. Nonspecific findings in histopathology pointed toward an impaired immune response in children. Selection of lesions and the site for biopsy also played a crucial role in the histopathological diagnosis.

Nearly 15% cases presented with signs of reaction in the current study; similar findings had been noted in previous studies.[5,7] Disability was noted among 24.7% of cases. Deformities in childhood cases were unfortunate and increased psychological and economic burden on the family as well as on the society. High prevalence of disability may be due to multibacillary disease, multiple nerve thickening, lack of awareness among the general population regarding the disease, delay in seeking treatment, and decreased index of suspicion by the healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

Although leprosy has been eliminated at the national level, areas of endemicity exist where the transmission continues to be high. Delhi being a region burdened by immigrant population from the neighboring states seeking health care, needs continuation of the elimination drive in the region. Apart from the case detection, it is also of utmost need to educate parents regarding treatment completion, as many stop treatment following subjective improvement. Childhood leprosy rate is an important marker of the ongoing active transmission in the community. Childhood leprosy still contributes to a significant proportion of the total case load, denoting the continuing active horizontal transmission of leprosy. Although the number of new cases registered annually has been decreasing, a much larger share of multibacillary cases is a reason for concern. Emphasis should be laid on health surveys for early detection and prompt referral of cases.

High rate of Grade 2 disability and leprosy reactions at presentation in our patients reinforced the need for early detection, through active search in community. Efforts on education and rehabilitation of these children would reduce the social impact.

Limitations

Limitations of the study included the retrospective design. Case detection was not active, thus missing the hidden cases in the community. The histopathology was not analyzed for details such as granuloma fraction. Being a hospital-based study, it might not reflect the actual scenario in the community.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chhabra N, Grover C, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN, Kaur R. Leprosy scenario at a tertiary level hospital in Delhi: A 5-year retrospective study. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:55–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.147793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dogra S, Narang T, Khullar G, Kumar R, Saikia UN. Childhood leprosy through the post-leprosy-elimination era: A retrospective analysis of epidemiological and clinical characteristics of disease over eleven years from a tertiary care hospital in North India. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:296–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becx-Bleumink M, Berhe D. Occurrence of reactions, their diagnosis and management in leprosy patients treated with multidrug therapy; experience in the leprosy control program of the All Africa Leprosy and Rehabilitation Training Center (ALERT) in Ethiopia. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1992;60:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO expert committee on leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1988;768:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Leprosy Eradication Programme Progress Report for 2014-15. New Delhi: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grover C, Nanda S, Garg VK, Reddy BS. An epidemiologic study of childhood leprosy from Delhi. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:489–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur I, Kaur S, Sharma VK, Kumar B. Childhood leprosy in Northern India. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:21–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1991.tb00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singal A, Sonthalia S, Pandhi D. Childhood leprosy in a tertiary-care hospital in Delhi, India: A reappraisal in the post-elimination era. Lepr Rev. 2011;82:259–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad PV. Childhood leprosy in a rural hospital. Indian J Pediatr. 1998;65:751–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02731059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayal R, Hashmi NA, Mathur PP, Prasad R. Leprosy in childhood. Indian Pediatr. 1990;27:170–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Beers SM, Hatta M, Klatser PR. Patient contact is the major determinant in incident leprosy: Implications for future control. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1999;67:119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar B, Rani R, Kaur I. Childhood leprosy in Chandigarh; clinico-histopathological correlation. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2000;68:330–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sehgal VN, Rege VL, Mascarenhas MF, Reys M. The prevalence and pattern of leprosy in a school survey. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1977;45:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvapandian A, Muliyil J, Joseph A, Kuppusamy P, Martin GG. School-survey in a rural leprosy endemic area. Lepr India. 1980;52:209–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burman KD, Rijall A, Agrawal S, Agarwalla A, Verma KK. Childhood leprosy in eastern Nepal: A hospital-based study. Indian J Lepr. 2003;75:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehgal VN, Joginder Leprosy in children: Correlation of clinical, histopathological, bacteriological and immunological parameters. Lepr Rev. 1989;60:202–5. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19890026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadkarni NJ, Grugni A, Kini MS, Balakrishnan M. Childhood leprosy in Bombay: A clinico-epidemiological study. Indian J Lepr. 1988;60:173–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selvasekar A, Geetha J, Nisha K, Manimozhi N, Jesudasan K, Rao PS, et al. Childhood leprosy in an endemic area. Lepr Rev. 1999;70:21–7. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19990006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]