Abstract

Onychomycosis is a fungal nail infection, considered as a public health problem because it is contagious and it interferes with the quality of life. It has long and difficult treatment, with many side effects and high cost. Propolis extract (PE) is a potential alternative to conventional antifungal agents because it has low cost, accessibility, and low toxicity. Herein, we report the favorable response of PE in onychomycosis in three elderly patients.

KEY WORDS: Antifungal, onychomycosis, propolis extract

Introduction

Onychomycosis is a nail infection caused by fungi that feed on keratin.[1] Currently available antifungal drugs show a range of adverse effects, which may lead the patients to stop treatment. In this context, propolis extract (PE) proved to be effective in treating fungal infections preventing microbiological resistance to commercial antifungals.[2,3] Despite several advances in research on in vitro PE, there are few reports of cases proving its antifungal effectiveness in vivo.[4] Here, we report the effect of topical treatment with a commercially available PE solution in patients of onychomycosis. A commercially available PE solution was obtained from an apiary of hives of Apis mellifera L. bees from a farm of Cianorte City, Brazil.[5] The inclusion of elderly volunteers followed the standards imposed by the internal committee for ethics in research involving human subjects, registered under number 615643/2014.

Case Reports

Case 1

A female patient, 68 year old, retired, diagnosed with diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, had long periods of contact with farm animals and worked as a maid for a long time. She had mycoses in the toe and fingernails. It began in her hand 15 years earlier, with the appearance of white spots, which turned black over time, without itchy lesions, though she felt pain during local compression [Figures 1a and c]. She had undertaken treatment with antifungals in the past, but that failed to cure the condition. After being isolated from the nails, the pathogenic agents were cultured and identified as Candida tropicalis (fingernails) and Candida parapsilosis (toenails). In vitro tests resulted in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) values for PE of 273.43 mg/mL and 546.87 mg/mL, respectively. The PE application was done twice a day on the infected nails, after the usual cleaning of the affected areas. The patient was monitored monthly during the treatment period. After 1 year of treatment, a considerable decrease of the lesions was observed [Figures 1b and d], even though the fungi could still be found in the lesions.

Figure 1.

Case 1, onychomycosis by Candida parapsilosis (a) and by Candida tropicalis (c). After treatment with propolis extract (b and d)

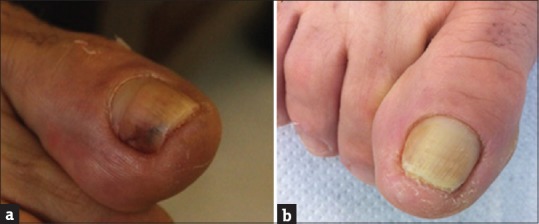

Case 2

A female patient, 69 year old, had onychomycosis on a toenail [Figure 2a]. It had yellowish color and hollow appearance with the absence of itching and presence of local pain. She had never confirmed the diagnosis with laboratory tests. The only treatment she had tried was with fluconazole, prescribed by a dermatologist for a year without clinical improvement. Subsequently, the collection and identification of the microorganism detected the presence of C. parapsilosis. In vitro, the fungus was subjected to MIC and MFC tests with PE and both showed the same value of 546.87 mg/mL. The patient was treated with PE (as in case 1) for 1 year. After this period, it was possible to observe the regression of white lesions in the nail [Figure 2b], negative KOH examination and there was an absence of fungal growth in the culture of collected samples.

Figure 2.

Case 2, onychomycosis by Candida parapsilosis (a). After treatment with application of propolis extract (b)

Case 3

A female patient, 65 year old, developed toenail mycosis. It had whitish color and hollow appearance [Figure 3a], an absence of itching and the presence of local pain. With laboratory tests indicating the presence of fungi, treatment with terbinafine was initiated and carried out for four months without any improvement. Later, fungal culture was done and identified as Fusarium solani. The patient was treated with PE (as in case 1 and 2) for 1 year. After this period, complete regression of onychomycosis was observed [Figure 3b]. No fungal elements were microscopically visualized and culture was negative.

Figure 3.

Case 3, onychomycosis by Fusarium solani (a). After treatment with propolis extract (b)

Discussion

The incidence of onychomycosis has risen in recent years in Maringá, following the global trend, coupled with the modernization of health services, including confirmatory laboratory tests, training of laboratory resources associated with the search for solutions to health problems.[6,7] In the present study, four nail samples were analyzed from three patients with clinical suspicion of onychomycosis of the toenails and the fingernails. They were evaluated with PE as a possible antifungal agent for onychomycosis treatment.

According to our results, only nondermatophyte fungi were isolated from patients with onychomycosis (one C. tropicalis, two C. parapsilosis, and one F. solani). Although the dermatophytes are the best-known cause of onychomycosis, studies show that infections caused by Candida spp.[1] and Fusarium spp.[7,8] have been increasing, mainly associated with paronychia.

Due to the fact that these agents are usually part of the skin microbiota (such as Candida spp.) or environmental contaminants (such as Fusarium spp.), they are commonly and unduly present in laboratory cultures. Thus, for greater reliability of these results, we followed rigorous laboratory criteria described by Guilhermetti et al., 2007, such as positive direct mycological examination, repetitive cultures, and absence of a truly pathogenic fungus in the sample.[8]

PE has been described as a promising alternative in the treatment against fungi. The chemical composition of PE is very complex; however, the researcher's attention is being drawn toward flavonoids.[9] This group of chemicals has already demonstrated antifungal potential,[10,11] however, its specific action against the fungal cells has not been well elucidated so far. Several studies have shown that PE has medicinal properties such as anti-inflammatory,[12] antibacterial,[13] and antifungal, showing activity in vitro against different species of fungi such as Candida spp., Fusarium spp., and Trichophyton spp.[2,3,7,9] Although, it is not well established how this compound promotes cell death, in vitro studies have shown that PE has an important role in the host-fungus relationship, since it is able to increase significantly reactive oxygen species production, oxygen consumption, microbicidal activity, and myeloperoxidase activity of human neutrophils against different isolates of C. albicans.[14] However, little has been published in relation to in vivo activity of PE. Most of the in vivo studies suggested the beneficial roles of PE on experimental wound healing, and this has also been approved in the clinical trial studies.[15]

In our in vitro experiments, PE was able to inhibit Candida spp. like other cases in the literature.[2,4] In vivo, four nails were treated with PE of which two of them showed complete resolution. Culture was negative. The other two nails showed a reduction of over 50% of the lesion; however, fungi were still isolated. Based on the results obtained during in vitro studies as well as results obtained from tests performed after topical treatment, it can be concluded that propolis possesses antifungal potential and is a promising therapeutic option in cases of onychomycosis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Professor Marco Antonio Costa for following the patients and providing the PE.

References

- 1.Silva-Rocha WP, de Azevedo MF, Chaves GM. Epidemiology and fungal species distribution of superficial mycoses in Northeast Brazil. J Mycol Med. 2017;27:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobaldini-Valerio FK, Bonfim-Mendonça PS, Rosseto HC, Bruschi ML, Henriques M, Negri M, et al. Propolis: A potential natural product to fight Candida species infections. Future Microbiol. 2016;11:1035–46. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2015-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veiga FF, Gadelha MC, da Silva MR, Costa MI, de Castro-Hoshino LV, Sato F, et al. Propolis extract for onychomycosis topical treatment: From bench to clinic. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:779. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capoci IR, Bonfim-Mendonça PD, Arita GS, Pereira RR, Consolaro ME, Bruschi ML, et al. Propolis is an efficient fungicide and inhibitor of biofilm production by vaginal Candida albicans. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2015. 2015:28769. doi: 10.1155/2015/287693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcucci MC. Propolis: Chemical composition, biological properties and therapeutic activity. Apidologie. 1995;26:83–99. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martelozo IC, Guilhermetti E, Svidzinski TI. Ocorrência de onicomicose em Maringá, Estado do Paraná, Brasil. Acta Sci Health Sci. 2005;27:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galletti J, Tobaldini-Valerio FK, Silva S, Kioshima ÉS, Trierveiler-Pereira L, Bruschi M, et al. Antibiofilm activity of propolis extract on Fusarium species from onychomycosis. Future Microbiol. 2017;12:1311–21. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2017-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guilhermetti E, Takahachi G, Shinobu CS, Svidzinski TI. Fusarium spp. As agents of onychomycosis in immunocompetent hosts. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:822–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siqueira AB, Gomes BS, Cambuim I, Maia R, Abreu S, Souza-Motta CM, et al. Trichophyton species susceptibility to green and red propolis from brazil. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009;48:90–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firdaus S, Ali F, Sultana N. Dermatophytosis (Qooba) a misnomer infection and its management in modern and unani perspective - A comparative review. J Med Plants. 2016;4:109–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agüero MB, Svetaz L, Baroni V, Lima B, Luna L, Zacchino S, et al. Urban propolis from San Juan province (Argentina): Ethnopharmacological uses and antifungal activity against Candida and dermatophytes. Ind Crops Prod. 2014;57:166–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lima Cavendish R, de Souza Santos J, Belo Neto R, Oliveira Paixão A, Valéria Oliveira J, Divino de Araujo E, et al. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of brazilian red propolis extract and formononetin in rodents. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;173:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohdaly AA, Mahmoud AA, Roby MH, Smetanska I, Ramadan MF. Phenolic extract from propolis and bee pollen: Composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. J Food Biochem. 2015;39:538–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alves de Lima NC, Ratti BA, Souza Bonfim Mendonça P, Murata G, Araujo Pereira RR, Nakamura CV, et al. Propolis increases neutrophils response against Candida albicans through the increase of reactive oxygen species. Future Microbiol. 2018;13:221–30. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2017-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oryan A, Alemzadeh E, Moshiri A. Potential role of propolis in wound healing: Biological properties and therapeutic activities. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;98:469–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]